-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Oisín Fitzgerald, Silke Dyer, Fernando Zegers-Hochschild, Elena Keller, G David Adamson, Georgina M Chambers, Gender inequality and utilization of ART: an international cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis, Human Reproduction, Volume 39, Issue 1, January 2024, Pages 209–218, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dead225

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

What is the association between a country’s level of gender equality and access to ART, as measured through ART utilization?

ART utilization is associated with a country’s level of gender equality even after controlling for the level of development.

Although gender equality is recognized as an important determinant of population health, its association with fertility care, a highly gendered condition, has not been explored.

A longitudinal cross-national analysis of ART utilization in 69 countries during 2002–2014 was carried out.

The Gender Inequality Index (GII), Human Development Index (HDI), and their component indicators were modelled against ART utilization using univariate regression models as well as mixed-effects regression methods (adjusted for country, time, and economic/human development) with multiple imputation to account for missing data.

ART utilization is associated with the GII. In an HDI-adjusted analysis, a one standard deviation decrease in the GII (towards greater equality) is associated with a 59% increase in ART utilization. Gross national income per capita, the maternal mortality ratio, and female parliamentary representation were the index components most predictive of ART utilization.

Only ART was used rather than all infertility treatments (including less costly and non-invasive treatments such as ovulation induction). This was a country-level analysis and the results cannot be generalized to smaller groups. Not all modelled variables were available for each country across 2002–2014.

Access to fertility care is central to women’s sexual and reproductive health, to women’s rights, and to human rights. As gender equality improves, so does access to ART. This relation is likely to be reinforcing and bi-directional, with progress towards global, equitable access to fertility care also improving women’s status and participation in societies.

External funding was not provided for this study. G.D.A. declares consulting fees from Labcorp and CooperSurgical. G.D.A. is the founder and CEO of Advanced Reproductive Care, Inc., as well as the Chair of the International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ICMART) and the World Endometriosis Research Foundation, both of which are unpaid roles. G.M.C. is an ICMART Board Representative, which is an unpaid role, and no payments are received from ICMART to UNSW, Sydney, or to G.M.C. to undertake this study. O.F., S.D., F.Z.-H., and E.K. report no conflicts of interest.

N/A.

Introduction

Infertility affects approximately one in six couples attempting to conceive, causing suffering to an estimated >48 million couples worldwide (Cox et al., 2022). It represents an increasingly important public health problem, as recently highlighted by the World Health Organization (WHO) (World Health Organization, 2020). Despite 20–40% of cases of infertility being caused by male factors (Kumar and Singh, 2015), and a further 10–38% of cases being contributed to by both male and female factors (Thonneau et al., 1991), infertility and its treatment remain a largely gendered problem with the medical and social burden falling disproportionally on women while in many settings access to care is determined by men (Chu et al., 2019; Kroes et al., 2023). Fertility care is a core component of reproductive healthcare along with pregnancy care and contraception (or family planning), and the level of reproductive health in a country is a clear signal of a woman’s status in society (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division, 2017). While variation in available pregnancy care and contraception have been shown to be major contributors to gender inequality around the world, even greater than female empowerment and economic independence (United Nations Development Programme, 2010), the relation between infertility treatment and gender equality has been less fully elucidated. As such, this article investigates whether the use of ART is related to established measures of gender inequality.

The treatment of infertility has been revolutionized over the last 40 years with the advent of ART (often referred to as IVF). Approximately 2.9 million ART cycles are performed each year globally and >8 million children are estimated to have been born since 1978 (Chambers et al., 2021). However, there is enormous variation in ART use among countries and regions (DeWeerdt, 2020), ranging from <30 cycles per million population (cpm) in a number of Asian and African countries to 5203 ART cpm in Israel (Chambers et al., 2021). Even within geographic regions, there is much variation, with a 2017 European report recording values ranging from 723 ART cpm in Poland to 3286 ART cpm in the Czech Republic (The European IVF-Monitoring Consortium for the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology et al., 2021). Equitable health systems should harmonize availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality (OHCHR, 2008). Realized access to, or utilization of, health services is the most measurable proxy for equity in health systems. In the case of ART, ART utilization, measured as cpm, is hence the most common metric used globally for access to care (Dyer et al., 2020).

Many factors are known to impact ART utilization including cost (Chambers et al., 2014), mandated public/private health insurance coverage (Kawwass et al., 2021), education (Omobude et al., 2022), religious beliefs (Inhorn, 2006), race/ethnicity (Almquist et al., 2022), and geographical isolation (Lazzari et al., 2022). ART is expensive at approximately US$12 000 per cycle (the global range spans from several thousand dollars to $25 000) so unsurprisingly the relative affordability of treatment both at an individual and country level strongly predicts utilization (Chambers et al., 2014). Wealthier countries generally have more ART clinics and higher utilization levels per capita (Chambers et al., 2021). However, wealth alone fails to explain variation in availability and utilization. Socio-cultural factors impact the level of acceptability of ART treatment, for example the use of donor gametes (Inhorn, 2006), and may create structural barriers to accessing treatment, for example through variation in legalization and funding (Präg and Mills, 2017). These socio-cultural factors do not necessarily disappear as a country’s level of wealth, or perhaps more importantly their level of development, grows [e.g. as reflected by composite measures accounting for wealth, education, and healthcare, such as the Human Development Index (HDI) (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2019)]. An important component of this socio-cultural variation is gender norms. Among similarly developed countries there is variation in the level of gender equality (Gaye et al., 2010) which, as mentioned, is often most pronounced in the areas of pregnancy care and contraception. However, the degree to which this may also impact access to ART has not been investigated on a global scale.

The aims of this study were to: identify whether there is an association between gender (in)equality and utilization of ART globally while controlling for a country’s level of development and investigate which dimensions of gender equality drive the association. This was performed by analysing the association between ART utilization and United Nations (UN) indices of gender equality (Gender Inequality Index, GII) and human development (HDI) and by examining which dimensions of GII and HDI where most predictive of ART utilization.

Materials and methods

Data sources

The research dataset was constructed by linking data on ART utilization across 74 countries from 2002 to 2014 to UN and World Bank measures of gender equality and human development, noting that not all indicators were consistently available for every country. A summary of data sources is presented in Table 1.

| Dependent variable, UNDP indices, and their component indicators . | Source . | Index . |

|---|---|---|

| ART utilization (ART cycles per million population) | ICMART | – |

| GII | UNDP | – |

| Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births) | World Bank | GII |

| Adolescent birth rate (births per 1000 women aged 15–19 years) | World Bank | GII |

| Male and female educational attainment: at least completed lower secondary, 25+ years (%) | UNESCO | GII |

| Female share of parliament seats (%) | World Bank | GII |

| Male and female labour force participation (% of total population aged 15+ years) | World Bank | GII |

| HDI | UNDP | – |

| Life expectancy at birth (years) | World Bank | HDI |

| Expected years of schooling | UNDP | HDI |

| Mean years of schooling | UNDP | HDI |

| Gross national income per capita (PPP, international $) | World Bank | HDI |

| Dependent variable, UNDP indices, and their component indicators . | Source . | Index . |

|---|---|---|

| ART utilization (ART cycles per million population) | ICMART | – |

| GII | UNDP | – |

| Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births) | World Bank | GII |

| Adolescent birth rate (births per 1000 women aged 15–19 years) | World Bank | GII |

| Male and female educational attainment: at least completed lower secondary, 25+ years (%) | UNESCO | GII |

| Female share of parliament seats (%) | World Bank | GII |

| Male and female labour force participation (% of total population aged 15+ years) | World Bank | GII |

| HDI | UNDP | – |

| Life expectancy at birth (years) | World Bank | HDI |

| Expected years of schooling | UNDP | HDI |

| Mean years of schooling | UNDP | HDI |

| Gross national income per capita (PPP, international $) | World Bank | HDI |

GII: Gender Inequality Index; HDI: Human Development Index; ICMART: International Committee for Monitoring ART; PPP: purchasing power parity; UNESCO: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; UNDP: United Nations Development Programme.

| Dependent variable, UNDP indices, and their component indicators . | Source . | Index . |

|---|---|---|

| ART utilization (ART cycles per million population) | ICMART | – |

| GII | UNDP | – |

| Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births) | World Bank | GII |

| Adolescent birth rate (births per 1000 women aged 15–19 years) | World Bank | GII |

| Male and female educational attainment: at least completed lower secondary, 25+ years (%) | UNESCO | GII |

| Female share of parliament seats (%) | World Bank | GII |

| Male and female labour force participation (% of total population aged 15+ years) | World Bank | GII |

| HDI | UNDP | – |

| Life expectancy at birth (years) | World Bank | HDI |

| Expected years of schooling | UNDP | HDI |

| Mean years of schooling | UNDP | HDI |

| Gross national income per capita (PPP, international $) | World Bank | HDI |

| Dependent variable, UNDP indices, and their component indicators . | Source . | Index . |

|---|---|---|

| ART utilization (ART cycles per million population) | ICMART | – |

| GII | UNDP | – |

| Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births) | World Bank | GII |

| Adolescent birth rate (births per 1000 women aged 15–19 years) | World Bank | GII |

| Male and female educational attainment: at least completed lower secondary, 25+ years (%) | UNESCO | GII |

| Female share of parliament seats (%) | World Bank | GII |

| Male and female labour force participation (% of total population aged 15+ years) | World Bank | GII |

| HDI | UNDP | – |

| Life expectancy at birth (years) | World Bank | HDI |

| Expected years of schooling | UNDP | HDI |

| Mean years of schooling | UNDP | HDI |

| Gross national income per capita (PPP, international $) | World Bank | HDI |

GII: Gender Inequality Index; HDI: Human Development Index; ICMART: International Committee for Monitoring ART; PPP: purchasing power parity; UNESCO: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; UNDP: United Nations Development Programme.

ART utilization

ART utilization, measured as the number of ART treatment cycles performed per million population (cpm), was sourced from the International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ICMART) World Reports, years 2002–2014 (https://www.icmartivf.org/reports-publications/, see Supplementary Data File S1 for a full list of data sources), which reports on ART treatments, effectiveness, and outcomes from ∼80 countries each year. A detailed overview of how ART utilization is calculated, and the process involved in producing the ICMART World Reports can be found in Chambers et al. (2021). Briefly, data are submitted to ICMART from regional and country representatives, with validation occurring at source, after submission through logic checks performed by an independent academic institution and finally clinical checks by ICMART. Of the 86 countries reporting to ICMART over the period, 10 were excluded from the analysis owing to inconsistent reporting (Bahrain, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates), and 2 (Taiwan and Syria) owing to lack of available data in the UN and World Bank measures outlined below. See Supplementary Table S1 for a full list of countries included in the analysis.

GII and HDI

The GII is a composite index that aims to quantify inequality in achievements between women and men within a country (Gaye et al., 2010). It has been reported every 5 years until 2010 and annually thereafter and uses three dimensions—reproductive health, measured by maternal mortality ratio (MMR) and adolescent birth rates (ABR); empowerment, measured by proportion of parliamentary seats occupied by females and proportion of adult females and males aged 25 years and older with at least some secondary education; and economic status, measured by labour force participation rate of female and male populations aged 15 years and older. The GII takes values between 0 and 1, with higher GII values indicating higher inequalities and thus higher loss to human development.

The UNDP HDI is a composite UNDP index for men and women equally, defined in terms of a long and healthy life, measured by life expectancy; knowledge, measured as expected and mean years of schooling; and a decent standard of living measured as gross national income (GNI) per capita. The HDI is perhaps the most well-known of the UNDP indices and is reported each year to rank countries into four tiers of human development.

Additionally, the nine component indicators that are used to construct the GII and HDI were sourced from the World Bank (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/) and the UNDP websites (https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/documentation-and-downloads) (Supplementary Data File S1).

Statistical analysis

Exploratory data analysis

Exploratory analysis using bivariate plots of ART utilization (cpm) and the GII and HDI indices, and their nine component indicators was performed. The log transform was used on ART utilization to achieve a more normal univariate distribution (the Box-Cox transformation statistic was 0.26). Simple ordinary least squares (or robust M-estimator method in the case of outliers) regression models were used to model bivariate relationships of ART utilization and GII and HDI, and the nine components for 2014 data (the most recent year). The model and an R2 statistic are reported graphically. Observations with missing data were excluded (on a variable-by-variable case) from this aspect of the analysis.

Statistical models

Modelling overview

To simultaneously assess the relation between ART utilization and both the indices (index model) and their components (component model) while accounting for the longitudinal nature of the data, linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) (multilevel) with country-level random intercepts were fitted. LMMs model both the between and within-country effect of an independent variable through a single coefficient, a weighted average of both effects (see Chapter 8 of Fitzmaurice et al., 2012). For a particular country, these models have the functional form:

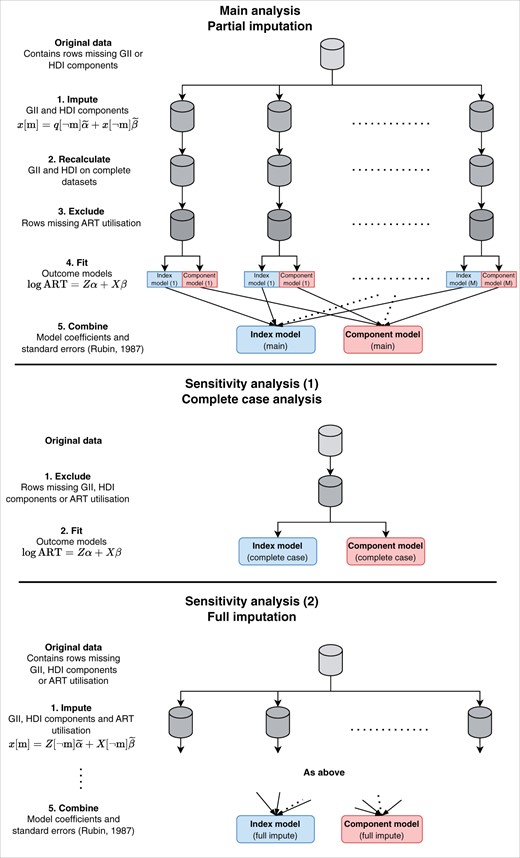

where is a country-level random intercept, corresponds to the impact of time (year) , are the fixed effect coefficients for model-independent variables , and is an irreducible error. The independent variables that form the model-independent variables are described below. The models were estimated using penalized maximum likelihood (Laird and Ware, 1982; Bates et al., 2015). All independent variables were scaled to have zero mean and unit SD for model estimation. The units indicated below are the original units. The model outcome in both cases, namely ART utilization, was log transformed and scaled to have a zero mean. To account for missing data in the covariates, data imputation procedures were used to create 100 synthetically complete datasets with the models estimated over each dataset, and estimates combined using the methods outlined in Rubin (1987) (more details below). A graphical overview of the modelling process can be found in Fig. 1.

Overview of statistical modelling. The main analysis consisted of imputation of missing HDI or GII components across 2002–2014 and fitting of LMMs with the indices (index model) and index components (component model) as the independent variables and log ART utilization (ART cycles per million population) as the outcome. Additional sensitivity analyses were performing using only complete cases and performing imputation of both the independent variables and the outcome. GII: Gender Inequality Index; HDI: Human Development Index; LMM: linear mixed-effects model.

Index model

The index model answers the first aim of this study: to identify whether there is an association between gender (in)equality and utilization of ART globally while controlling for a country’s level of development. We fit a random intercept LMM with the independent variables listed below.

Time (measured in years)

GII

HDI

Component model

The component model answers the second aim: to investigate which dimensions of gender equality drive any association between gender (in)equality and utilization of ART globally while controlling for a country’s level of development. We fit a random intercept LMM with shrinkage of the fixed effects with the independent variables listed below (mean years of schooling were not used as it was highly correlated with expected years of schooling).

Time (measured in years)

GII components:

MMR (per 100 000 live births)

ABR (births per 1000 women aged 15–19 years)

Difference between male and female educational attainment (% difference in lower secondary school completion in those 25+ years) (school gap)

Female share of parliament seats (%)

Difference between male and female labour force participation (% difference in 15+ years) (labour gap)

HDI components:

Life expectancy at birth (years)

Expected years of schooling

GNI per capita (purchasing-power parity, international $)

For the component model, multicollinearity of the independent variables was a concern. As a result, a ridge (L2) penalty was added to the model loss function to stabilize the estimation of the fixed effects. This penalty results in the sum of the squared fixed effect coefficients for the component model being constrained to be less than a prespecified value. A greater penalty is equivalent to reducing the effective degrees of freedom of the model. The degree of shrinkage was chosen graphically as the minimum value that stabilized the coefficients in a plot of the model coefficients versus effective degrees of freedom. The coefficients are considered to have stabilized if any changes with increased penalization are gradual, in this case corresponding to a loss of one degree of freedom.

Partial imputation

The dataset contained missing values in the following independent variables: GII (officially calculated only in 2005 and annually for 2010–2014), educational attainment (51%), parliamentary representation (3%), and labour force participation (11%), where the percentages are reported for cases where ART utilization was available. To account for this, an imputation analysis was performed using a multilevel joint model for the data estimated using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) (Carpenter and Kenward, 2013). This approach assumes that the missingness was random conditional on the information available in the dataset. To assess the convergence of the MCMC procedure the R-hat statistic was used (Gelman and Rubin, 1992). The imputation was performed with a burn-in period of 2500, and M = 100 artificially complete datasets. All component variables mentioned in the component model section were used in the imputation procedure.

Sensitivity analyses

In addition to estimating the model parameters on the datasets with imputation of the independent variables (partial imputation—‘main model’), we fitted the following two models for sensitivity analyses: complete case analysis, which excludes any row in the dataset with a missing value, and full imputation analysis, with imputation of both the outcome and the independent variables. Over the 12 available years, ART utilization was missing in 29% of cases where at least one other piece of information (e.g. a GII or HDI component) was available.

Model fit measures

The marginal and conditional R2 (percentage of variability explained by the models) were calculated using the methods described in Nakagawa and Schielzeth (2013). The marginal R2 only accounts for the fixed effects terms and is generally lower than the conditional R2, the variance explained by the whole model including the random effects.

Data and code availability

We followed the STROBE checklist (von Elm et al., 2007) to increase the transparency of reporting and make our data and analysis code available at github.com/CBDRH/gii-art-utilisation. The analysis was performed using R (R Core Team, 2021) and utilized the following libraries: data.table, ggplot2, MuMIn, mitml, and lme4.

Results

Exploratory data analysis

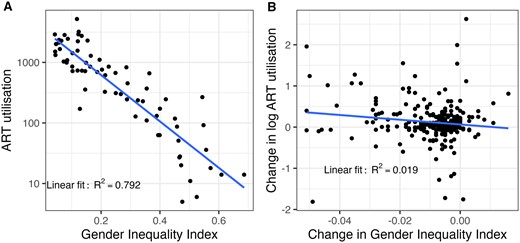

Visual inspection showed a strong cross-sectional (between-country) and weak longitudinal (within-country) relation between GII and ART utilization, with a low value of GII (i.e. high gender equality) associated with high ART utilization (Fig. 2a and b). The simple (univariate) regression model implies a 0.1 decrease in the GII is associated with a doubling in ART utilization across countries (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table S2). The longitudinal data within countries show the tendency for countries which on average decreased in GII over the period 2005–2014 to have increased in log ART utilization (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table S3).

The relation between the GII and ART utilization (ART cycles per million population). (A) ART utilization and the GII in 2014 with fitted OLS linear model. (B) Change in log ART utilization and change in GII by country for the period 2005, 2010–2014, with fitted OLS linear model. GII: Gender Inequality Index; OLS: ordinary least squares.

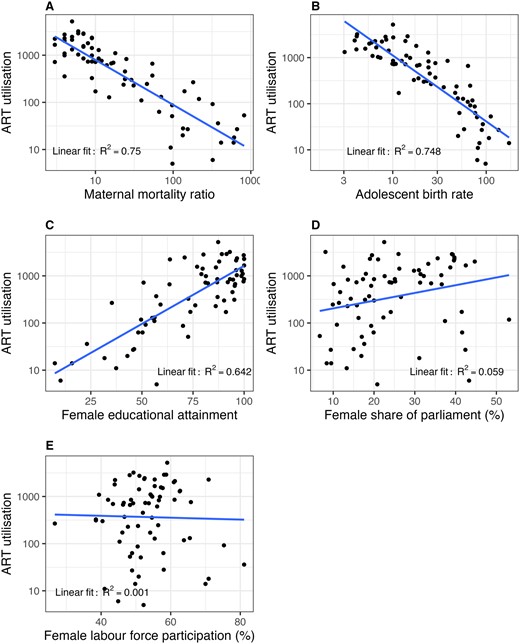

The component indicators of the health dimension of the GII, the ‘maternal mortality ratio (MMR)’ and ‘adolescent birth rate (ABR)’, have the strongest bivariate relations with ART utilization. The empowerment indicators, ‘female share of parliamentary seats’ and ‘female population with at least secondary education’, have moderate bivariate relations with ART utilization. The sole measure of the labour market dimension, ‘female labour force participation’, had no obvious relation with ART utilization. While only 2014 data are shown in Fig. 3, a similar bivariate relation was found for all years of observation. The correlations between the components are presented in Supplementary Table S4.

Cross-sectional relations between ART utilization (ART cycles per million population) and select components of the GII in 2014 with added OLS linear model. (A) ART utilization and the maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live birth). (B) ART utilization and the adolescent birth rate (births per 1000 women aged 15–19 years). (C) ART utilization and female educational attainment (% of 25+ years who have completed at least lower secondary). (D) ART utilization and female share of parliamentary seats (%). (E) ART utilization and female labour force participation (% of total population aged 15+ years). GII: Gender Inequality Index; OLS: ordinary least squares.

Statistical modelling

Imputation

The R-hat measures suggested the MCMC imputation procedure achieved adequate levels of converge (R-hat statistics distributed tightly around 1.0) (Supplementary Tables S5 and S6).

Index model

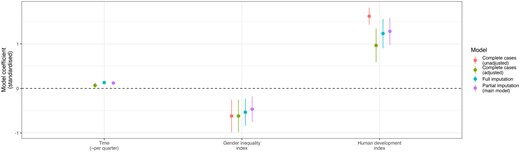

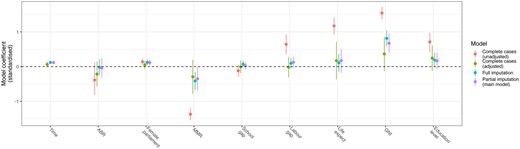

The index LMM (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Tables S7, S8, and S9) shows that, after controlling for human development, we still see a significant and meaningful effect for gender equality. The results are consistent across the main model and sensitivity analyses, broadly showing that a one SD unit decrease in the GII is associated with a 0.5 SD unit increase in log ART utilization. On the percentage change scale, we find that a one SD movement in the GII (a change of 0.177 units) towards greater gender equality is associated with an increase in ART utilization by 59% (95% CI: 19–110%), when controlling for a country’s level of economic and human development through the HDI. The overall model explained 77% of the variation in ART utilization (complete cases (adjusted)).

Index model results. The unadjusted models are LMMs that adjust for country and time but not the remaining variables. The variables are standardized, and the coefficients can be interpreted as the amount of change in log ART utilization for a one SD increase in the variable. The full results can be found in Supplementary Tables S7, S8, and S9. LMMs: linear mixed-effects models.

Component model

The component LMM found that female parliamentary representation, MMR, and GNI per capita were the most predictive of ART utilization following variable selection through shrinkage (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Tables S10, S11, and S12). Given the strong correlation between covariates and high-level analysis, these significant covariates are best interpreted as being representative of underlying concepts (in this case female empowerment, reproductive health, and level of economic development). A 10% (one SD) increase in female parliamentary representation corresponded to a 12% (95% CI: 3–22%) increase in ART use. A 175 deaths per 100 000 women (one SD) decrease in the MMR corresponded to a 42% (95% CI: 0–102%) increase in ART use. A $15 210 (one SD) increase in the GNI corresponded to a 96% (95% CI: 47–161%) increase in ART use.

Component model results. The unadjusted models are LMMs that adjust for country and time but not the remaining variables. The variables are standardized, and the coefficients can be interpreted as the amount of change in log ART utilization for a one SD increase in the variable. After adjustment only time, female parliamentary representation, MMR, and GNI are significant for all or some of the models. The full results can be found in Supplementary Tables S10, S11, and S12. GNI: gross national income; LMMs: linear mixed-effects models; MMR: maternal mortality ratio.

Discussion

This study represents a novel analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal data to generate evidence that country-level gender equality and human development can reasonably explain women’s access to ART treatment. To our knowledge, it is the first quantitative analysis of this topic. Additional strengths include highlighting which aspects, or components, of gender equality are likely responsible for the relation and the creation of a publicly available dataset that can be used for further research on the topic. The study found that a one SD movement in the GII (change of 0.177 units) towards greater gender equality is associated with an increase in ART utilization by 85% (95% CI: 73–97%), with this association holding for all magnitudes of change in the GII. The component model showed that the elements of the GII and HDI indices that were most predictive of change were GNI, MMR, and female parliamentary representation. A one SD improvement in female parliamentary representation (increase by 10%), MMR (decrease by 175 deaths per 100 000 women), and GNI (increase by $15 210) corresponded to a 12% (95% CI: 3–22%), 42% (0–102%), and 96% (47–161%) increase in ART use, respectively.

These results confirm the importance of countries’ health and wealth in providing access to reproductive care to women and that these in themselves are an important component of gender equality. Not surprisingly, our study confirms that a country’s wealth (i.e. GNI) predicts the level of ART utilization. However, importantly for a gendered condition such as infertility, there was a clear effect of having women in positions of influence and decision-making, reflected in the association with female participation in parliament, to influence the likelihood of access to infertility treatment. Furthermore, the strong association of maternal mortality and ABR with access to ART reinforces the evidence that the level of reproductive health in a country also reflects the degree to which fertility care is treated as (or considered) a reproductive right (World Health Organization, 2020).

Perhaps because of the gendered nature associated with the social burden and medical treatment of infertility, and the high fertility rates in many low- and middle-income countries, access to ART is not high on most public health policy agendas. Indeed, the cost of each ART cycle is well out-of-reach of most women (median out-of-pocket costs per cycle in the USA: US$16 000, higher than the 2014 worldwide per-capita GNI US$10 037) (Wu et al., 2014), making access to affordable treatment reliant on legislation that enforces public funding of ART treatment. There is arguably no other medical treatment that exhibits such varying arrangements for public funding (Chambers et al., 2020). In the latest global survey of ART practices and policies undertaken by the International Federation of Fertility Societies, only half (53%) of the 88 countries who submitted data reported any type of financial support for ART treatment and only 22 offered full funding (IFFS, 2022). Clearly, there is a long way to go towards making ART a treatment option for all women.

While the current study does not attempt to disentangle the intersecting pathways and mechanisms that give rise to the complex relations between gender equality, human development, and ART utilization, they are likely to be bi-directional. For example, wealthier countries are more likely to offer public funding for ART. Conversely, making ART accessible and affordable increases gender equality by providing opportunities for women to fulfil their professional and personal life goals while preventing efforts and cost in the pursuit of futile but cheaper interventions. Accessible ART also reduces the gendered nature of infertility (Inhorn and Patrizio, 2015) through increased knowledge about infertility in the general population, normalizing infertility as a medical condition that can be treated, and reducing the stigma, blame, and social suffering associated with the condition (Inhorn and Patrizio, 2015). Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that countries can make meaningful improvements in gender equality, even while significant income differences between countries remain (Stotsky et al., 2016). This highlights that reproductive rights, such as ART access, should be a focus of policy in all countries regardless of the level of development. Indeed, a 2021 report on ART in Latin America emphasizes the impact policy can play, with Argentina and Uruguay having greater ART utilization than the rest of countries in the region, largely attributable to more universal access to care (Zegers-Hochschild et al., 2021).

A limitation of this study is that only ART was used rather than all infertility treatments (including less costly and non-invasive treatments such as ovulation induction) to draw possible inferences to overall reproductive health. However, evidence suggests that poor access to ART is associated with fragmented and low-quality non-ART treatment (Mohammed-Durosinlorun et al., 2019). Less costly forms of infertility treatment may be more commonly available than ART in low-resource countries, thus potentially leading to a biased reflection of overall reproductive health in our study given that these less costly treatments are not accounted for. However, such treatments are not effective to treat some of the most common causes of infertility (fallopian tubal disease and severe male factors). There are also very little national data on non-ART treatments, and therefore, it has been proposed that ART utilization be used as a proxy indicator of access to all infertility treatment more generally (Dyer et al., 2020). Furthermore, all aspects of sexual and reproductive health should be considered holistically from both a policy and translation perspective so that people can realize their reproductive rights and have access to safe, effective, and affordable family planning methods (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2019; Gipson et al., 2020).

Other limitations include that it is a country-level analysis, the presence of missing data, and the possibility of measurement errors in the indices provided by the World Bank and UN. The analysis was performed at the country level, and while the conclusions may hold at lower levels of resolution (e.g. the individual or family/community level), this is not guaranteed to be the case (Brewer and Venaik, 2014). Additional factors, difficult to account for in country-level analyses, may impact ART utilization between communities in the same country, such as systemic racism (Almquist et al., 2022; Seifer et al., 2022). ART utilization was not available for 28% of observations across the 13 years included in the analysis (31 countries had complete ART utilization data), and the GII was only officially calculated for 2005 and annually for 2010–2014. Unfortunately, as data on educational attainment were also unavailable for these years, it was not possible to independently calculate the GII for these years. Indeed, among GII and HDI components, educational attainment had the largest degree of missingness (51%), followed by labour force participation (11%) and parliamentary representation (3%). Additionally, countries with low ART clinic reporting rates, predominantly in the Middle East and North Africa, were excluded from the analysis. However, sensitivity analyses suggested inclusion of these countries would not meaningfully alter the conclusions.

The importance of gender inequality and infertility is being increasingly recognized by international health and development bodies making our study a valuable contribution to this area. Gender equality is a fundamental human right, reflected in the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 5 (SDG 5: achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls). It is also critical to achieving other SDG health goals, including SDG 3: to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all. There is also increasing awareness of the relation between gender equality and ‘health for all’, particularly the health of children (Pratley, 2016). Of note, The Lancet dedicated a series of papers to Gender Equality, Norms, and Health in 2019 (Darmstadt et al., 2019) highlighting the ‘substantial impact of gender inequalities and restrictive gender norms in health risks and behaviours’ and proposing an agenda for action to reduce gender inequality and shift gender norms for improved health outcomes. The series supports the findings of this study by concluding that real ‘progress requires political will, and leaders and decision-makers in health must act on the [available] evidence to overcome the barriers that impede progress’. Even more directly, the WHO has recently recognized infertility as a key component of sexual and reproductive health, highlighted its fundamental rooting in women’s and human rights, and made a commitment to collaborate with partners to conduct global epidemiological and aetiological research into infertility. Our study contributes to this understanding and provides new evidence in support of infertility treatment to be considered holistically from both a policy and translation perspective (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2019; Gipson et al., 2020).

In conclusion, utilization of ART varies dramatically across the globe, a fact that is not attributable solely to differences in economic development between countries. Rather, variations in gender equality also play a role, with greater gender equality associated with improved access to ART. The relation between these factors is likely complex and bi-directional. We hope that this article serves to spur further research and policy development to advance equitable access to fertility and reproductive care, the importance of which has been highlighted by bodies such as the WHO and UN.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Human Reproduction online.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study and analysis code are openly available at https://github.com/CBDRH/gii-art-utilisation.

Acknowledgements

ICMART gratefully acknowledges all country and regional representatives, and the ART centres they represent, who submit data to the ICMART World Registry. Additionally, thanks to the data analysts who prepared the ICMART, World Bank, and United Nations data for publication/download and to the anonymous referees for their feedback on this article.

Authors’ roles

O.F., S.D., F.Z.-H., G.D.A., and G.M.C. conceptualized the study. O.F. and G.M.C. designed the study and planned the analysis. E.K. prepared the STROBE checklist. O.F. performed the formal statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to data interpretation, critically revised subsequent drafts, and read and approved the submitted version. All authors had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Funding

There was no explicit funding to undertake this study.

Conflict of interest

G.D.A. declares consulting fees from Labcorp and CooperSurgical. G.D.A. is the founder and CEO of Advanced Reproductive Care, Inc., as well as the Chair of the International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ICMART) and the World Endometriosis Research Foundation, both of which are unpaid roles. G.M.C. is an ICMART Board Representative, which is an unpaid role, and no payments are received from ICMART to UNSW, Sydney, or to G.M.C. to undertake this study. O.F., S.D., F.Z.-H., and E.K. report no conflicts of interest.