-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

F. Mol, N.M. van Mello, A. Strandell, D. Jurkovic, J.A. Ross, T.M. Yalcinkaya, K.T. Barnhart, H.R. Verhoeve, G.C. Graziosi, C.A. Koks, B.W. Mol, W.M. Ankum, F. van der Veen, P.J. Hajenius, M. van Wely, for the European Surgery in Ectopic Pregnancy (ESEP) study group, Ineke C. A. H. Janssen, Harry Kragt, Annemieke Hoek, Trudy C. M. Trimbos-Kemper, Frank J. M. Broekmans, Wim N. P. Willemsen, A. B. Dijkman, A. L. Thurkow, H. J. H. M. van Dessel, P. J. Q. van der Linden, F. W. Bouwmeester, G. J. E. Oosterhuis, J. J. van Beek, M. H. Emanuel, H. Visser, J. P. R. Doornbos, P. J. M. Pernet, J. Friederich, Karin Strandell, Lars Hogström, Ingmar Klinte, F. Pettersson, Z. Sabetirad, K. Nilsson, G. Tegerstedt, J. J. Platz-Christensen, for the European Surgery in Ectopic Pregnancy (ESEP) study group, Cost-effectiveness of salpingotomy and salpingectomy in women with tubal pregnancy (a randomized controlled trial), Human Reproduction, Volume 30, Issue 9, September 2015, Pages 2038–2047, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev162

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Is salpingotomy cost effective compared with salpingectomy in women with tubal pregnancy and a healthy contralateral tube?

Salpingotomy is not cost effective over salpingectomy as a surgical procedure for tubal pregnancy, as its costs are higher without a better ongoing pregnancy rate while risks of persistent trophoblast are higher.

Women with a tubal pregnancy treated by salpingotomy or salpingectomy in the presence of a healthy contralateral tube have comparable ongoing pregnancy rates by natural conception. Salpingotomy bears the risk of persistent trophoblast necessitating additional medical or surgical treatment. Repeat ectopic pregnancy occurs slightly more often after salpingotomy compared with salpingectomy. Both consequences imply potentially higher costs after salpingotomy.

We performed an economic evaluation of salpingotomy compared with salpingectomy in an international multicentre randomized controlled trial in women with a tubal pregnancy and a healthy contralateral tube. Between 24 September 2004 and 29 November 2011, women were allocated to salpingotomy (n = 215) or salpingectomy (n = 231). Fertility follow-up was done up to 36 months post-operatively.

We performed a cost-effectiveness analysis from a hospital perspective. We compared the direct medical costs of salpingotomy and salpingectomy until an ongoing pregnancy occurred by natural conception within a time horizon of 36 months. Direct medical costs included the surgical treatment of the initial tubal pregnancy, readmissions including reinterventions, treatment for persistent trophoblast and interventions for repeat ectopic pregnancy. The analysis was performed according to the intention-to-treat principle.

Mean direct medical costs per woman in the salpingotomy group and in the salpingectomy group were €3319 versus €2958, respectively, with a mean difference of €361 (95% confidence interval €217 to €515). Salpingotomy resulted in a marginally higher ongoing pregnancy rate by natural conception compared with salpingectomy leading to an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio €40 982 (95% confidence interval −€130 319 to €145 491) per ongoing pregnancy. Since salpingotomy resulted in more additional treatments for persistent trophoblast and interventions for repeat ectopic pregnancy, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was not informative.

Costs of any subsequent IVF cycles were not included in this analysis. The analysis was limited to the perspective of the hospital.

However, a small treatment benefit of salpingotomy might be enough to cover the costs of subsequent IVF. This uncertainty should be incorporated in shared decision-making. Whether salpingotomy should be offered depends on society's willingness to pay for an additional child.

Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development, Region Västra Götaland Health & Medical Care Committee.

ISRCTN37002267.

Introduction

Ectopic pregnancy affects 1–2% of all pregnant women (Barnhart, 2009). Most ectopic pregnancies are located in the Fallopian tube, and surgery is generally accepted as the treatment of first choice (Hajenius et al., 2007). Historically, surgical treatment involved a radical approach, i.e. salpingectomy, to achieve rapid haemostasis since tubal rupture was usually present. From 1957 onwards, the concept of preservation of the tube was propagated over ablative surgery to maintain women's fertility (Miller, 1957). Nowadays, early diagnosis has enabled conservative surgery by salpingotomy. Salpingotomy preserves the tube, but carries the risks of persistent trophoblast and repeat tubal pregnancy in the same tube. Salpingectomy minimizes these risks, but leaves only one tube available for conception, which might reduce fertility potential.

We recently completed the European Surgery in Ectopic Pregnancy (ESEP) study, an international multicentre randomized controlled trial to compare the effectiveness of salpingotomy with salpingectomy in women with tubal pregnancy (Mol et al., 2014). We randomly assigned women with a laparoscopically confirmed tubal pregnancy and a healthy contralateral tube to either salpingotomy or salpingectomy. A healthy tube was defined as a tube with a normal macroscopic aspect during surgery. To assess fertility after surgery, researchers contacted the participants every 6 months for 36 months. If an ongoing pregnancy did not occur, follow-up ended at the last date of contact, or at the moment when either IVF or reconstructive tubal surgery was done. This trial showed a non-significantly higher rate of ongoing pregnancy by natural conception within a time horizon of 36 months after salpingotomy compared with salpingectomy. However, there were significantly more women with persistent trophoblast and there was a slightly higher but non-significant repeat ectopic pregnancy rate after salpingotomy.

As the two arms of the trial had comparable ongoing pregnancy rates, but showed differences in persistent trophoblast and repeat ectopic pregnancy rates, costs may then play an important role in deciding which treatment should prevail. Salpingotomy incurs additional costs of routine post-operative blood tests (serum hCG) to detect persistent trophoblast in a significant number of women. If present, this adds the costs of systemic methotrexate treatment and occasional surgical re-intervention. A higher rate of repeat ectopic pregnancy also implies higher costs. Salpingectomy is supposed to be a less costly treatment option, as it usually involves a single operation, and a repeat ectopic pregnancy in the same tube occurs very rarely. The aim of this study was to calculate the costs of both treatments and provide an economic evaluation of salpingotomy compared with salpingectomy.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The economic evaluation was conducted alongside the ESEP study. This trial was an international multicentre randomized controlled trial that compared salpingotomy and salpingectomy in women with a tubal pregnancy and a healthy contralateral tube (Mol et al., 2014). Women were eligible for the trial if they had a presumptive diagnosis of tubal pregnancy and were scheduled for surgery. At surgery, the presence of a tubal pregnancy had to be confirmed. Women were not eligible if the condition of the contralateral tube was so abnormal according to the surgeon, that future pregnancy was unlikely in case the woman was randomly assigned to salpingectomy (e.g. hydrosalpinx, severe peri tubal adhesions or malformations). Salpingotomy and salpingectomy were performed following local procedural standards used in the participating hospitals. Salpingotomy was converted to salpingectomy and laparoscopy was converted to open surgery when clinically necessary. Serum hCG was followed weekly until it became undetectable in both study groups, to detect persistent trophoblast. Women were contacted every 6 months for a period of 36 months to assess fertility.

A total of 450 women were enrolled in the trial between 24 September 2004 and 29 November 2011. Four women from one hospital were excluded owing to the inability of that hospital to provide any data on these women. Thus, of 446 women, 215 were randomly allocated salpingotomy and 231 were randomly allocated to salpingectomy. In February 2013, the trial was completed. Twenty-four women (5.4%) were lost to fertility follow-up, 11 (5.1%) in the salpingotomy group and 13 (5.6%) in the salpingectomy group (P-value 0.82).

Ongoing pregnancy by natural conception was comparable in both groups. The cumulative ongoing pregnancy rate was 60.7% after salpingotomy and 56.2% after salpingectomy (fecundity rate ratio 1.06; 95% CI, 0.81–1.38; Log rank test P-value 0.678).

Persistent trophoblast occurred more frequently in the salpingotomy group than in the salpingectomy group: 14 (7%) versus 1 (<1%); rate ratio 15; 95% CI 2.0–113.4. Repeat ectopic pregnancy occurred in 18 women (8%) in the salpingotomy group versus 12 (5%) in the salpingectomy group (rate ratio 1.6; 95% CI 0.8–3.3).

Economic evaluation

For the cost analysis we used data from the 446 randomized women. The economic evaluation was designed as a cost-effectiveness analysis, with ongoing pregnancy by natural conception as the clinical outcome (Briggs and O'Brien, 2001). Since comparable cumulative ongoing pregnancy rates were found after salpingotomy and salpingectomy, the secondary outcome measures persistent trophoblast and repeat ectopic pregnancy became relevant for clinical decision-making and were therefore also evaluated as clinical outcomes in this analysis.

The cost analysis was performed from a hospital perspective. Because in the Dutch Health Care system the hospitals bill the patient's insurance company and are managed on a non-profit basis, these calculated costs were an appropriate measure of the societal cost of direct medical care. In this study only costs of medical interventions (direct costs) were taken into account.

In this study we also included costs of repeat ectopic pregnancy although we did not observe a significant difference in repeat ectopic pregnancy rate between salpingotomy and salpingectomy. In a cost-effectiveness analysis, all actual costs are included also of rare events where it is virtually impossible to reach adequate power to prove statistical difference. Costs of repeat ectopic pregnancy were therefore included in both groups.

Resource use

Resource utilization was documented using individual patient data from the case record form. For each patient, we registered and measured the duration of surgery to perform salpingotomy or salpingectomy, conversions to salpingectomy and/or open surgery, blood transfusions, hospital stay, re-admittances and re-interventions, additional systemic methotrexate treatment or laparoscopic salpingectomy to treat persistent trophoblast, and interventions for repeat ectopic pregnancy.

Duration of surgery was defined as time spent in the operating theatre calculated as the interval between the start of general anaesthesia induction and the end of the anaesthesia. The number of disposable bipolar cutting forceps for complete salpingectomy was assumed to equal the number of salpingectomies performed. We used one type of bipolar cutting forceps for unit cost reference (Cutting forceps®, ACMI USA). The number of serum hCG measurements to detect persistent trophoblast were calculated for salpingotomy (weekly serum hCG until undetectable level) and for salpingectomy (one serum hCG measurement post-operatively at the post-operative consultation in the outpatient clinic).

Missing data for duration of surgery and serum hCG monitoring after salpingotomy were imputed using the multiple method (Manca and Palmer, 2005). Resource utilization in terms of diagnostic work-up for the index ectopic pregnancy or any suspected repeat ectopic pregnancy and subfertility work-up or assisted reproductive technology (ART) was not taken into account.

Unit costs

Unit costs were estimated with different methods and sources, all according to recent guidelines on costing and health care services (Table I). Recourse unit prices reflected the use of medical staff, materials, equipment, housing, depreciation and overheads. Costs were expressed in euro (€). Standardized unit costs were calculated for the Academic Medical Centre Amsterdam, The Netherlands based on actual expenses made during the trial, using the most recently available unit prices of the year 2009. Subsequently, unit costs were applied to resource use observed in all participating centres.

Cost analysis: units of resource use, unit costs, valuation method and volume source.

| . | Unit . | Unit cost (euro) . | Valuation method (source) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial admission | |||

| First admission day* | Day | 794 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Additional hospital stay | Day | 638 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Laparoscopy start up | Standard associated costs of operation | 355 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Theatre | Minute | 5.66 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Conversion to open surgery materials | Material | 177 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Disposable cutting forceps | Material | 343 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Blood transfusion | Gift | 208 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Re-laparoscopy with salpingectomy | Procedure | 1450 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Post-operatively | |||

| Serum hCG measurement order | Measurement | 12.90 | Dutch costing guideline^ |

| Serum hCG measurement | Measurement | 10.36 | Dutch Health Authority fares$ |

| Consultation by telephone | Consultation | 52 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Consultation outpatient clinic | Consultation | 138 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Readmission | |||

| Hospital admission | Day | 638 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Diagnostic laparoscopy* | Procedure | 525 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Laparoscopic salpingectomy | Procedure | 1450 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Surgical exploration at trocar site* | Procedure | 525 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Persistent trophoblast | |||

| Systemic methotrexate | |||

| Kidney, liver function lab tests | Measurement | 20 | Dutch Health Authority fares$ fares |

| Methotrexate dosage | Milligram | 0.21 | Pharmaco therapeutic compass# |

| Day care methotrexate | Day | 547 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Serum hCG measurement order | Measurement | 12.90 | Dutch costing guideline |

| Serum hCG measurement | Measurement | 10.36 | Dutch Health Authority fares$ fares |

| Consultation by telephone | Consultation | 52 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Salpingectomy | |||

| Salpingectomy by laparoscopy | Procedure | 1450 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Hospital admission | Day | 638 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Repeat ectopic pregnancy | |||

| Laparoscopic salpingotomy (€1750) plus 1 admission day (€794) | Procedure | 2544 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Laparoscopic salpingectomy (€1450) plus one admission day (€794) | Procedure | 2244 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Single dose methotrexate | Procedure | 697 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Multiple dose methotrexate | Procedure | 2787 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Expectant management | Procedure | 200 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| . | Unit . | Unit cost (euro) . | Valuation method (source) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial admission | |||

| First admission day* | Day | 794 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Additional hospital stay | Day | 638 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Laparoscopy start up | Standard associated costs of operation | 355 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Theatre | Minute | 5.66 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Conversion to open surgery materials | Material | 177 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Disposable cutting forceps | Material | 343 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Blood transfusion | Gift | 208 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Re-laparoscopy with salpingectomy | Procedure | 1450 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Post-operatively | |||

| Serum hCG measurement order | Measurement | 12.90 | Dutch costing guideline^ |

| Serum hCG measurement | Measurement | 10.36 | Dutch Health Authority fares$ |

| Consultation by telephone | Consultation | 52 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Consultation outpatient clinic | Consultation | 138 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Readmission | |||

| Hospital admission | Day | 638 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Diagnostic laparoscopy* | Procedure | 525 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Laparoscopic salpingectomy | Procedure | 1450 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Surgical exploration at trocar site* | Procedure | 525 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Persistent trophoblast | |||

| Systemic methotrexate | |||

| Kidney, liver function lab tests | Measurement | 20 | Dutch Health Authority fares$ fares |

| Methotrexate dosage | Milligram | 0.21 | Pharmaco therapeutic compass# |

| Day care methotrexate | Day | 547 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Serum hCG measurement order | Measurement | 12.90 | Dutch costing guideline |

| Serum hCG measurement | Measurement | 10.36 | Dutch Health Authority fares$ fares |

| Consultation by telephone | Consultation | 52 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Salpingectomy | |||

| Salpingectomy by laparoscopy | Procedure | 1450 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Hospital admission | Day | 638 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Repeat ectopic pregnancy | |||

| Laparoscopic salpingotomy (€1750) plus 1 admission day (€794) | Procedure | 2544 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Laparoscopic salpingectomy (€1450) plus one admission day (€794) | Procedure | 2244 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Single dose methotrexate | Procedure | 697 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Multiple dose methotrexate | Procedure | 2787 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Expectant management | Procedure | 200 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

*Duration of surgery mean 30 min.

^Reference Dutch Costing Guideline (Hakkaart-van Roijen et al., 2010).

#Pharmaco therapeutic compass (College voor Zorgverzekeringen, 2011).

$Hospital pricelist of Dutch Health Authority 2012 (Nederlandse Zorg Autoriteit, www.nza.nl).

Cost analysis: units of resource use, unit costs, valuation method and volume source.

| . | Unit . | Unit cost (euro) . | Valuation method (source) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial admission | |||

| First admission day* | Day | 794 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Additional hospital stay | Day | 638 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Laparoscopy start up | Standard associated costs of operation | 355 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Theatre | Minute | 5.66 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Conversion to open surgery materials | Material | 177 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Disposable cutting forceps | Material | 343 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Blood transfusion | Gift | 208 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Re-laparoscopy with salpingectomy | Procedure | 1450 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Post-operatively | |||

| Serum hCG measurement order | Measurement | 12.90 | Dutch costing guideline^ |

| Serum hCG measurement | Measurement | 10.36 | Dutch Health Authority fares$ |

| Consultation by telephone | Consultation | 52 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Consultation outpatient clinic | Consultation | 138 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Readmission | |||

| Hospital admission | Day | 638 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Diagnostic laparoscopy* | Procedure | 525 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Laparoscopic salpingectomy | Procedure | 1450 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Surgical exploration at trocar site* | Procedure | 525 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Persistent trophoblast | |||

| Systemic methotrexate | |||

| Kidney, liver function lab tests | Measurement | 20 | Dutch Health Authority fares$ fares |

| Methotrexate dosage | Milligram | 0.21 | Pharmaco therapeutic compass# |

| Day care methotrexate | Day | 547 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Serum hCG measurement order | Measurement | 12.90 | Dutch costing guideline |

| Serum hCG measurement | Measurement | 10.36 | Dutch Health Authority fares$ fares |

| Consultation by telephone | Consultation | 52 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Salpingectomy | |||

| Salpingectomy by laparoscopy | Procedure | 1450 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Hospital admission | Day | 638 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Repeat ectopic pregnancy | |||

| Laparoscopic salpingotomy (€1750) plus 1 admission day (€794) | Procedure | 2544 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Laparoscopic salpingectomy (€1450) plus one admission day (€794) | Procedure | 2244 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Single dose methotrexate | Procedure | 697 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Multiple dose methotrexate | Procedure | 2787 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Expectant management | Procedure | 200 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| . | Unit . | Unit cost (euro) . | Valuation method (source) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial admission | |||

| First admission day* | Day | 794 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Additional hospital stay | Day | 638 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Laparoscopy start up | Standard associated costs of operation | 355 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Theatre | Minute | 5.66 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Conversion to open surgery materials | Material | 177 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Disposable cutting forceps | Material | 343 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Blood transfusion | Gift | 208 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Re-laparoscopy with salpingectomy | Procedure | 1450 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Post-operatively | |||

| Serum hCG measurement order | Measurement | 12.90 | Dutch costing guideline^ |

| Serum hCG measurement | Measurement | 10.36 | Dutch Health Authority fares$ |

| Consultation by telephone | Consultation | 52 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Consultation outpatient clinic | Consultation | 138 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Readmission | |||

| Hospital admission | Day | 638 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Diagnostic laparoscopy* | Procedure | 525 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Laparoscopic salpingectomy | Procedure | 1450 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Surgical exploration at trocar site* | Procedure | 525 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Persistent trophoblast | |||

| Systemic methotrexate | |||

| Kidney, liver function lab tests | Measurement | 20 | Dutch Health Authority fares$ fares |

| Methotrexate dosage | Milligram | 0.21 | Pharmaco therapeutic compass# |

| Day care methotrexate | Day | 547 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Serum hCG measurement order | Measurement | 12.90 | Dutch costing guideline |

| Serum hCG measurement | Measurement | 10.36 | Dutch Health Authority fares$ fares |

| Consultation by telephone | Consultation | 52 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Salpingectomy | |||

| Salpingectomy by laparoscopy | Procedure | 1450 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Hospital admission | Day | 638 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Repeat ectopic pregnancy | |||

| Laparoscopic salpingotomy (€1750) plus 1 admission day (€794) | Procedure | 2544 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Laparoscopic salpingectomy (€1450) plus one admission day (€794) | Procedure | 2244 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Single dose methotrexate | Procedure | 697 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Multiple dose methotrexate | Procedure | 2787 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

| Expectant management | Procedure | 200 | Direct costs from academic hospital |

*Duration of surgery mean 30 min.

^Reference Dutch Costing Guideline (Hakkaart-van Roijen et al., 2010).

#Pharmaco therapeutic compass (College voor Zorgverzekeringen, 2011).

$Hospital pricelist of Dutch Health Authority 2012 (Nederlandse Zorg Autoriteit, www.nza.nl).

Statistical analysis

All outcomes were analysed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Costs were calculated by multiplying the quantity of resource use and unit costs. Costs were expressed as means and medians per woman. We split costs into four categories: initial surgery, readmission (for other reasons than persistent trophoblast), persistent trophoblast and repeat ectopic pregnancy. The difference in total direct medical costs was expressed as a mean difference.

Costs were combined with the clinical outcomes by calculating incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICER). An ICER was defined as the ratio of the difference in costs and the difference in effectiveness between two interventions, which reflects the costs needed to obtain one extra unit in health outcome. We calculated ICERs for ongoing pregnancy by natural conception, persistent trophoblast and repeat ectopic pregnancy. So, the reported ICERs reflect the costs needed to gain one ongoing pregnancy by natural conception, or to prevent one case of persistent trophoblast, or to prevent one case of repeat ectopic pregnancy. For the outcome ongoing pregnancy by natural conception, contingency table analysis was used to calculate the difference in effectiveness compared with survival analysis in the original paper.

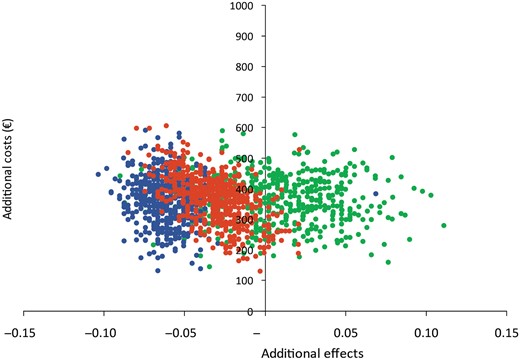

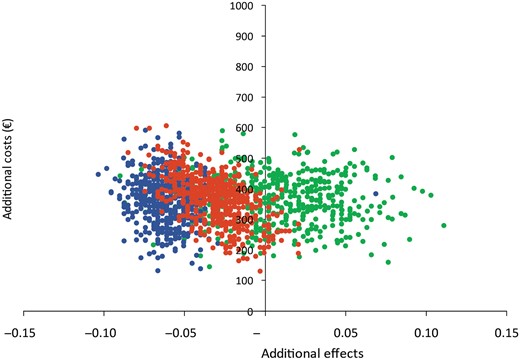

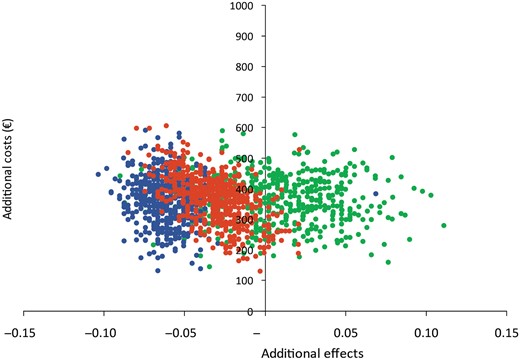

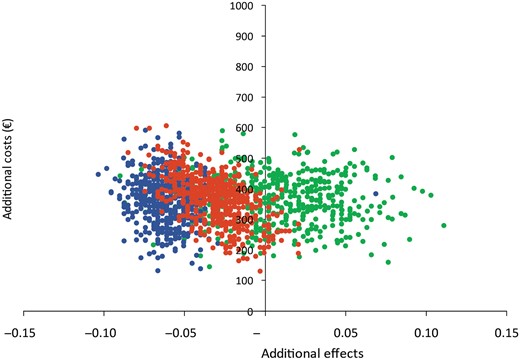

Statistical uncertainty around the difference in mean costs and ICERs was expressed with 95% CI, estimated by 1000 bootstrap replications. Bootstrapping is based on generating multiple data sets, using sampling with replacement from the original data and calculating the statistic of interest in each set (Barber and Thompson, 2000). Uncertainty of the ICERs was visualized by plotting a cost-effectiveness plane and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (Black, 1990). Salpingectomy was the reference strategy (in the origin of the cost-effectiveness plane). Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves visualized the increasing probability that salpingotomy is cost-effective for the measured effect when increasing the willingness-to-pay threshold.

Sensitivity and scenario analysis

To explore the effect of plausible changes in key variables, a sensitivity analysis was performed. Key variables comprised unit costs of hospital admission and unit costs of use of the operating theatre. Model 1 assumes an overall 30% higher admission costs and operating theatre costs, whereas model 2 assumes an overall 30% lower costs to reflect different cost levels in other countries of hospital types, for example general hospitals.

A scenario analysis was performed to evaluate the costs in a scenario in which women return the next day for surgery in a day-care surgery unit compared with the current situation with immediate hospital admission and waiting for an operation room to become available (model 3). Such a scenario would be possible in women diagnosed with tubal pregnancy who are haemodynamically stable and relatively asymptomatic, suggesting a low suspicion of impending tubal rupture. Other scenarios were: a scenario in which disposable bipolar cutting forceps are replaced by re-usable materials (model 4), a scenario with limited serum hCG monitoring after salpingotomy using a serum hCG clearance curve and in which no serum hCG monitoring is done after salpingectomy (model 5), and a scenario with only a home urinary pregnancy test 6 weeks after salpingotomy and no serum hCG monitoring after salpingectomy (model 6). In view of model 5 and 6, women had (weekly) serum hCG monitoring after salpingotomy and salpingectomy in the trial. It is realistic to propose that post-operative serum hCG measurement is not required after salpingectomy since the risk of persistent trophoblast was <1%. After salpingotomy, persistent trophoblast can be detected early by plotting a single serum hCG measurement within the first week after surgery in the standard serum hCG clearance curve after salpingotomy (Hajenius et al., 1995).

All statistical, economic and simulation analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 (Chicago, IL, USA) and MICROSOFT EXCEL 2003.

Ethical approval

One institutional review board in each country approved the study protocol, after which the boards of directors of all other participating centres provided local approval. Participants provided written informed consent.

Results

Resource use

Initial admission

Laparoscopy was attempted in all women (Table II). Both after salpingotomy and salpingectomy, three women (1%) had a conversion to open surgery. Reasons for these conversions were impaired vision because of intra-abdominal adhesions or blood clots, or technical difficulties with laparoscopy in obese women. In the salpingotomy group, 43 women (20%) had a conversion to salpingectomy because of persistent uncontrollable bleeding. The mean duration of surgery of the procedures was 90 min for salpingotomy and 75 min for salpingectomy (mean difference −15 min; 95% CI −22 to −8).

| . | Salpingotomy . | Salpingectomy . |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 215) . | (n = 231) . | |

| Initial admission | ||

| Duration of the surgery—mean in minutes (SD) | 90 (39) | 75 (32) |

| Conversion to open surgery | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) |

| Conversion to salpingectomy | 43 (20%) | NA |

| Re-laparoscopy with salpingectomy for suspected bleeding | 2 (1%) | NA |

| Blood transfusion | 14 (7%) | 7 (3%) |

| Blood transfusion: total no. units | 32 | 17 |

| Serum hCG measurements including consultation by telephone | 691 | 141 |

| Consultations outpatient clinic | 215 | 231 |

| Readmission | 15 (5%) | 5 (2%) |

| Repeat laparoscopy with salpingectomy for suspected bleeding | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Other surgical reintervention | 4 (2%) | 2 (1%) |

| Readmission onlya | 10 (5%) | 3 (1%) |

| Readmission days—no. | 38 | 18 |

| Persistent trophoblast | 14 (7%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Single dose regimen methotrexate | 7 (2%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Single dose and additional dose methotrexate | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Multiple dose regimen methotrexate | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Readmission with repeat laparoscopy with salpingectomy for persistent trophoblast | 5 (2%) | 0 |

| Repeat ectopic pregnancy | 18 (8%) | 12 (5%) |

| Laparoscopic salpingotomy | 6 (3%) | 2 (1%) |

| Laparoscopic salpingectomy | 8 (4%)b | 7 (3%) |

| Methotrexate—multiple dose | 1 (<1%) | 2 (1%) |

| Methotrexate—single dose | 3 (1%) | 0 |

| Expectant management | 0 | 1 (<1%) |

| . | Salpingotomy . | Salpingectomy . |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 215) . | (n = 231) . | |

| Initial admission | ||

| Duration of the surgery—mean in minutes (SD) | 90 (39) | 75 (32) |

| Conversion to open surgery | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) |

| Conversion to salpingectomy | 43 (20%) | NA |

| Re-laparoscopy with salpingectomy for suspected bleeding | 2 (1%) | NA |

| Blood transfusion | 14 (7%) | 7 (3%) |

| Blood transfusion: total no. units | 32 | 17 |

| Serum hCG measurements including consultation by telephone | 691 | 141 |

| Consultations outpatient clinic | 215 | 231 |

| Readmission | 15 (5%) | 5 (2%) |

| Repeat laparoscopy with salpingectomy for suspected bleeding | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Other surgical reintervention | 4 (2%) | 2 (1%) |

| Readmission onlya | 10 (5%) | 3 (1%) |

| Readmission days—no. | 38 | 18 |

| Persistent trophoblast | 14 (7%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Single dose regimen methotrexate | 7 (2%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Single dose and additional dose methotrexate | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Multiple dose regimen methotrexate | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Readmission with repeat laparoscopy with salpingectomy for persistent trophoblast | 5 (2%) | 0 |

| Repeat ectopic pregnancy | 18 (8%) | 12 (5%) |

| Laparoscopic salpingotomy | 6 (3%) | 2 (1%) |

| Laparoscopic salpingectomy | 8 (4%)b | 7 (3%) |

| Methotrexate—multiple dose | 1 (<1%) | 2 (1%) |

| Methotrexate—single dose | 3 (1%) | 0 |

| Expectant management | 0 | 1 (<1%) |

Data are n (%).

aOne woman was admitted for abdominal pain during single dose MTX treatment for persistent trophoblast.

bOne salpingotomy patient had two repeat ectopic pregnancies, only the first was taken into account, which was located in the contralateral tube and treated by partial salpingectomy. The second occurred in the tubal remnant which then was removed completely.

| . | Salpingotomy . | Salpingectomy . |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 215) . | (n = 231) . | |

| Initial admission | ||

| Duration of the surgery—mean in minutes (SD) | 90 (39) | 75 (32) |

| Conversion to open surgery | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) |

| Conversion to salpingectomy | 43 (20%) | NA |

| Re-laparoscopy with salpingectomy for suspected bleeding | 2 (1%) | NA |

| Blood transfusion | 14 (7%) | 7 (3%) |

| Blood transfusion: total no. units | 32 | 17 |

| Serum hCG measurements including consultation by telephone | 691 | 141 |

| Consultations outpatient clinic | 215 | 231 |

| Readmission | 15 (5%) | 5 (2%) |

| Repeat laparoscopy with salpingectomy for suspected bleeding | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Other surgical reintervention | 4 (2%) | 2 (1%) |

| Readmission onlya | 10 (5%) | 3 (1%) |

| Readmission days—no. | 38 | 18 |

| Persistent trophoblast | 14 (7%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Single dose regimen methotrexate | 7 (2%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Single dose and additional dose methotrexate | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Multiple dose regimen methotrexate | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Readmission with repeat laparoscopy with salpingectomy for persistent trophoblast | 5 (2%) | 0 |

| Repeat ectopic pregnancy | 18 (8%) | 12 (5%) |

| Laparoscopic salpingotomy | 6 (3%) | 2 (1%) |

| Laparoscopic salpingectomy | 8 (4%)b | 7 (3%) |

| Methotrexate—multiple dose | 1 (<1%) | 2 (1%) |

| Methotrexate—single dose | 3 (1%) | 0 |

| Expectant management | 0 | 1 (<1%) |

| . | Salpingotomy . | Salpingectomy . |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 215) . | (n = 231) . | |

| Initial admission | ||

| Duration of the surgery—mean in minutes (SD) | 90 (39) | 75 (32) |

| Conversion to open surgery | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) |

| Conversion to salpingectomy | 43 (20%) | NA |

| Re-laparoscopy with salpingectomy for suspected bleeding | 2 (1%) | NA |

| Blood transfusion | 14 (7%) | 7 (3%) |

| Blood transfusion: total no. units | 32 | 17 |

| Serum hCG measurements including consultation by telephone | 691 | 141 |

| Consultations outpatient clinic | 215 | 231 |

| Readmission | 15 (5%) | 5 (2%) |

| Repeat laparoscopy with salpingectomy for suspected bleeding | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Other surgical reintervention | 4 (2%) | 2 (1%) |

| Readmission onlya | 10 (5%) | 3 (1%) |

| Readmission days—no. | 38 | 18 |

| Persistent trophoblast | 14 (7%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Single dose regimen methotrexate | 7 (2%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Single dose and additional dose methotrexate | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Multiple dose regimen methotrexate | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Readmission with repeat laparoscopy with salpingectomy for persistent trophoblast | 5 (2%) | 0 |

| Repeat ectopic pregnancy | 18 (8%) | 12 (5%) |

| Laparoscopic salpingotomy | 6 (3%) | 2 (1%) |

| Laparoscopic salpingectomy | 8 (4%)b | 7 (3%) |

| Methotrexate—multiple dose | 1 (<1%) | 2 (1%) |

| Methotrexate—single dose | 3 (1%) | 0 |

| Expectant management | 0 | 1 (<1%) |

Data are n (%).

aOne woman was admitted for abdominal pain during single dose MTX treatment for persistent trophoblast.

bOne salpingotomy patient had two repeat ectopic pregnancies, only the first was taken into account, which was located in the contralateral tube and treated by partial salpingectomy. The second occurred in the tubal remnant which then was removed completely.

In the salpingotomy group, two women (1%) had an immediate re-laparoscopy with salpingectomy for suspected bleeding compared with no re-interventions after salpingectomy. Fourteen (7%) women allocated to salpingotomy and seven (3%) allocated to salpingectomy had one or more units of blood transfusion. The total number of units packed cells transfused was 32 after salpingotomy compared with 17 after salpingectomy.

Readmission

In the salpingotomy group, 15 women (5%) had a hospital readmission. One woman (<1%) had a repeat laparoscopy with salpingectomy for suspected bleeding. Four women (2%) had a readmission with another surgical reintervention: one superficial exploration because of an infected umbilical trocar site, one exploration of the umbilical port site because of suspected omentum interposition (no interposition found), one diagnostic laparoscopy for suspected appendicitis (no appendicitis found or other diagnosis made), and one diagnostic laparoscopy for suspected bleeding (tubal haematoma found). Ten women (5%) were clinically observed: eight because of abdominal pain, one for suspected venous thrombosis (no thrombosis found) and one for unknown reasons.

In the salpingectomy group, five women (2%) had a hospital readmission. In two women (1%) a surgical reintervention was done: one laparoscopy with abdominal evacuation of blood clots and one exploration for omental herniation through a lateral trocar site. Three women (1%) were clinically observed: one because of infection of the umbilical entrée (treated with antibiotics), one for pyelonephritis (treated with antibiotics) and one for suspected venous thrombosis.

Persistent trophoblast

In the salpingotomy group, 14 women (7%) underwent additional treatment for persistent trophoblast, 9 with systemic methotrexate and 5 by laparoscopic salpingectomy. There was one woman (<1%) with persistent trophoblast after salpingectomy. She was treated with systemic methotrexate.

Repeat ectopic pregnancy

In the salpingotomy group, 18 women (8%) were treated for repeat ectopic pregnancy: 6 women by laparoscopic salpingotomy, 8 women by laparoscopic salpingectomy, 1 woman was treated with multiple dose systemic methotrexate and 3 women with single dose systemic methotrexate. In the salpingectomy group, 12 women (5%) were treated for repeat ectopic pregnancy: 2 women by laparoscopic salpingotomy, 7 women by laparoscopic salpingectomy and 2 women were treated with multiple dose systemic methotrexate, and 1 woman was managed expectantly.

Costs

The composition of the mean and median costs is shown in Table III. Concerning the initial surgical procedure, the costs in the salpingotomy group and the salpingectomy group had a mean difference per woman of €89. For re-admissions with or without surgical intervention, the mean cost difference per woman was €79.

| . | Salpingotomy (n = 215) . | Salpingectomy (n = 231) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean . | Median (IQR) . | Mean . | Median (IQR) . | Cost diff. . | |

| Initial admission | 2874 | 2716 (2450–3065) | 2785 | 2736 (2349–2660) | |

| 89 | |||||

| Readmission | 134 | 0 (0–0) | 54 | 0 (0–0) | |

| 79 | |||||

| Persistent trophoblast | 134 | 0 (0–0) | 3 | 0 (0–0) | |

| 131 | |||||

| Repeat ectopic pregnancy | 177 | 0 (0–0) | 115 | 0 (0–0) | |

| 62 | |||||

| Total direct medical costs | 3319 | 2887 (2250–3673) | 2958 | 2736 (2599–3056) | |

| Differential mean cost* | 361 (217–515) | ||||

| (95% CI)# | |||||

| . | Salpingotomy (n = 215) . | Salpingectomy (n = 231) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean . | Median (IQR) . | Mean . | Median (IQR) . | Cost diff. . | |

| Initial admission | 2874 | 2716 (2450–3065) | 2785 | 2736 (2349–2660) | |

| 89 | |||||

| Readmission | 134 | 0 (0–0) | 54 | 0 (0–0) | |

| 79 | |||||

| Persistent trophoblast | 134 | 0 (0–0) | 3 | 0 (0–0) | |

| 131 | |||||

| Repeat ectopic pregnancy | 177 | 0 (0–0) | 115 | 0 (0–0) | |

| 62 | |||||

| Total direct medical costs | 3319 | 2887 (2250–3673) | 2958 | 2736 (2599–3056) | |

| Differential mean cost* | 361 (217–515) | ||||

| (95% CI)# | |||||

Costs used 2009.

IQR, interquartile range.

*Salpingotomy minus Salpingectomy.

#non-parametric confidence interval based on 1000 bootstrap replications.

| . | Salpingotomy (n = 215) . | Salpingectomy (n = 231) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean . | Median (IQR) . | Mean . | Median (IQR) . | Cost diff. . | |

| Initial admission | 2874 | 2716 (2450–3065) | 2785 | 2736 (2349–2660) | |

| 89 | |||||

| Readmission | 134 | 0 (0–0) | 54 | 0 (0–0) | |

| 79 | |||||

| Persistent trophoblast | 134 | 0 (0–0) | 3 | 0 (0–0) | |

| 131 | |||||

| Repeat ectopic pregnancy | 177 | 0 (0–0) | 115 | 0 (0–0) | |

| 62 | |||||

| Total direct medical costs | 3319 | 2887 (2250–3673) | 2958 | 2736 (2599–3056) | |

| Differential mean cost* | 361 (217–515) | ||||

| (95% CI)# | |||||

| . | Salpingotomy (n = 215) . | Salpingectomy (n = 231) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean . | Median (IQR) . | Mean . | Median (IQR) . | Cost diff. . | |

| Initial admission | 2874 | 2716 (2450–3065) | 2785 | 2736 (2349–2660) | |

| 89 | |||||

| Readmission | 134 | 0 (0–0) | 54 | 0 (0–0) | |

| 79 | |||||

| Persistent trophoblast | 134 | 0 (0–0) | 3 | 0 (0–0) | |

| 131 | |||||

| Repeat ectopic pregnancy | 177 | 0 (0–0) | 115 | 0 (0–0) | |

| 62 | |||||

| Total direct medical costs | 3319 | 2887 (2250–3673) | 2958 | 2736 (2599–3056) | |

| Differential mean cost* | 361 (217–515) | ||||

| (95% CI)# | |||||

Costs used 2009.

IQR, interquartile range.

*Salpingotomy minus Salpingectomy.

#non-parametric confidence interval based on 1000 bootstrap replications.

In the salpingotomy group, more costs were generated by persistent trophoblast (difference €131) as well as by repeat ectopic pregnancy (difference €62) compared with salpingectomy.

Overall, after salpingotomy the mean direct medical costs per woman (€3319) were higher than after salpingectomy (€2958). The mean difference in direct medical costs was €361 (95% CI €217 to €515).

Cost-effectiveness

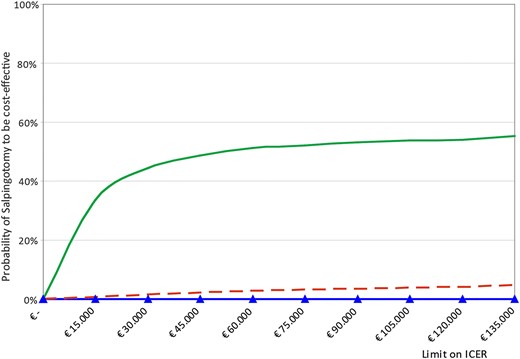

In combination with a small non-significant difference in cumulative ongoing pregnancy rates by natural conception in favour of salpingotomy (50.2% after salpingotomy compared with 49.4% after salpingectomy, absolute risk difference 0.9%, RR 1.02 95% CI 0.84–1.2), the ICER becomes positive (€40 983). The findings based on the bootstrap sample reflect the combined uncertainty about both the costs and the effectiveness estimates as shown in the cost-effectiveness plane (Fig. 1) and cost-acceptability curves (Fig. 2). In the probabilistic analysis, 1000 random samples were drawn from the data set and the resulting costs and effects were estimated for that sample. Each point in the cost-effectiveness plane represents the additional costs and health gain for salpingotomy compared with salpingectomy (Fig. 1). The ICER estimates for ongoing pregnancy rate by natural conception were mainly located in the upper right quadrant indicating that health gain is obtained at additional costs. However, the scatter spreads over both upper quadrants, indicating that our trial did not show a significant difference in ongoing pregnancy rate but did so in costs. The additional costs to gain one extra ongoing pregnancy by natural conception after salpingotomy was €40 983 (95% CI −€130 319 to €145 491). In the cost-effectiveness plane, the ICER estimates for persistent trophoblast and repeat ectopic pregnancy were mainly located in the upper left quadrant, which indicates health losses, but higher costs.

Cost-effectiveness plane. Each point in the cost-effectiveness plane represents the additional costs and health gain of salpingotomy compared with salpingectomy (multiple samples from original data set). Colour represents clinical outcome measures:  ongoing pregnancy by natural conception;

ongoing pregnancy by natural conception;  persistent trophoblast;

persistent trophoblast;  repeat ectopic pregnancy.

repeat ectopic pregnancy.

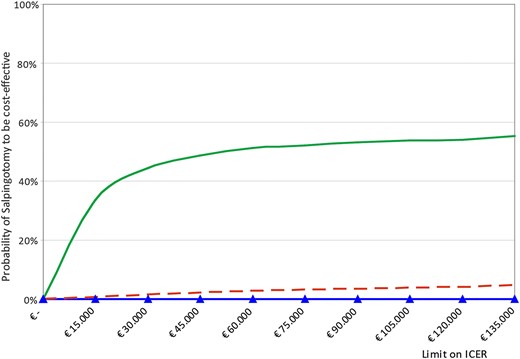

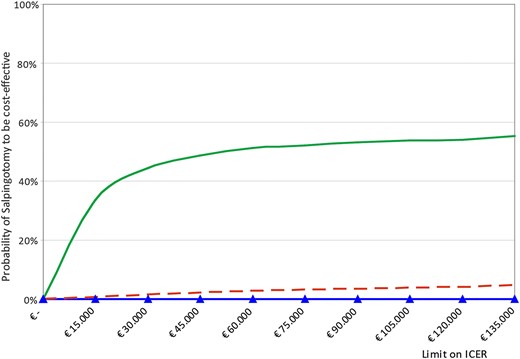

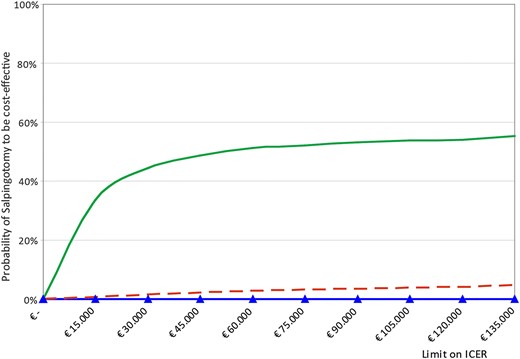

Cost-acceptability curves. Probability of salpingotomy to be cost-effective for different clinical outcomes. The probability increases as result of an increase in willingness to pay. Colour represents clinical outcome measure:  ongoing pregnancy by natural conception;

ongoing pregnancy by natural conception;  persistent trophoblast;

persistent trophoblast;  repeat ectopic pregnancy.

repeat ectopic pregnancy.

Salpingotomy was only cost-effective for the measured effects when the threshold for willingness-to-pay increased (Fig. 2).

Sensitivity and scenario analyses

The results of the sensitivity and scenario analyses are shown in Table IV. If hospital admission costs and operation theatre costs are increased by 30%, the difference would increase from €361 to €431 (95% CI €249 to €624), making salpingectomy less costly (model 1). When assuming hospital admission costs and operating theatre costs to be 30% less, the difference would decrease to €292 (95% CI €166 to €430), still leaving salpingectomy less costly (model 2).

| Univariate sensitivity analyses . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model . | Description . | Salpingotomy . | Salpingectomy . | Diff . | 95% CI# . | ICER (95% CI#) . | |

| 0 | Base case | 3319 | 2958 | 361 | 217 | 515 | 40 983 (−130 319 to 145 491) |

| 1* | Thirty per cent higher ward admission costs (€1032 for the first day and €829 for additional days), operation theatre costs (€461 start up and €7,36 per minute) and day care admission costs for methotrexate treatment for persistent trophoblast (€711). | 4076 | 3645 | 431 | 249 | 624 | 48.852 (−213 473 to 138 799) |

| 2* | Thirty per cent lower ward admission costs (€556 for the first day and €447 for additional days), operation theatre costs (€249 start up and €4,0 per minute) and day care admission costs for methotrexate treatment for persistent trophoblast (€383). | 2562 | 2270 | 292 | 166 | 430 | 33 113 (−2 146 449 to 118 570) |

| Scenario analyses | |||||||

| Model | Scenario | Salpingotomy | Salpingectomy | Diff | 95% CI# | ICER (95% CI#) | |

| 3* | Surgery in day care admission (€251), instead of ward admission until operation theatre available.^ | 2052 | 1754 | 297 | 169 | 437 | 33 730 (−149 544 to 124 372) |

| 4* | Replace disposable bipolar cutting forceps (€343) by re-usable bipolar forceps and re-usable scissors at no costs. | 3250 | 2615 | 636 | 478 | 798 | 72 097 (−234 791 to 204 129) |

| 5* | Replace weekly serum hCG follow-up after salpingotomy by one serum hCG measurement and no further follow-up if decline is according to serum hCG clearance curve. No serum hCG measurement after salpingectomy. | 3152 | 2912 | 240 | 100 | 381 | 27 264 (−92 252 to 109 817 |

| 6* | Replace weekly serum hCG follow-up by a home urinary pregnancy test 6 weeks after salpingotomy at no costs for home pregnancy test. No serum hCG measurement after salpingectomy. | 3077 | 2912 | 165 | 12 | 316 | 18 730 (−52 205 to 83 594) |

| Univariate sensitivity analyses . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model . | Description . | Salpingotomy . | Salpingectomy . | Diff . | 95% CI# . | ICER (95% CI#) . | |

| 0 | Base case | 3319 | 2958 | 361 | 217 | 515 | 40 983 (−130 319 to 145 491) |

| 1* | Thirty per cent higher ward admission costs (€1032 for the first day and €829 for additional days), operation theatre costs (€461 start up and €7,36 per minute) and day care admission costs for methotrexate treatment for persistent trophoblast (€711). | 4076 | 3645 | 431 | 249 | 624 | 48.852 (−213 473 to 138 799) |

| 2* | Thirty per cent lower ward admission costs (€556 for the first day and €447 for additional days), operation theatre costs (€249 start up and €4,0 per minute) and day care admission costs for methotrexate treatment for persistent trophoblast (€383). | 2562 | 2270 | 292 | 166 | 430 | 33 113 (−2 146 449 to 118 570) |

| Scenario analyses | |||||||

| Model | Scenario | Salpingotomy | Salpingectomy | Diff | 95% CI# | ICER (95% CI#) | |

| 3* | Surgery in day care admission (€251), instead of ward admission until operation theatre available.^ | 2052 | 1754 | 297 | 169 | 437 | 33 730 (−149 544 to 124 372) |

| 4* | Replace disposable bipolar cutting forceps (€343) by re-usable bipolar forceps and re-usable scissors at no costs. | 3250 | 2615 | 636 | 478 | 798 | 72 097 (−234 791 to 204 129) |

| 5* | Replace weekly serum hCG follow-up after salpingotomy by one serum hCG measurement and no further follow-up if decline is according to serum hCG clearance curve. No serum hCG measurement after salpingectomy. | 3152 | 2912 | 240 | 100 | 381 | 27 264 (−92 252 to 109 817 |

| 6* | Replace weekly serum hCG follow-up by a home urinary pregnancy test 6 weeks after salpingotomy at no costs for home pregnancy test. No serum hCG measurement after salpingectomy. | 3077 | 2912 | 165 | 12 | 316 | 18 730 (−52 205 to 83 594) |

*Scenario calculated in both arms.

#Non-parametric confidence interval based on 1000 bootstrap replications.

^Reference Dutch Costing Guideline (Hakkaart-van Roijen et al., 2010).

| Univariate sensitivity analyses . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model . | Description . | Salpingotomy . | Salpingectomy . | Diff . | 95% CI# . | ICER (95% CI#) . | |

| 0 | Base case | 3319 | 2958 | 361 | 217 | 515 | 40 983 (−130 319 to 145 491) |

| 1* | Thirty per cent higher ward admission costs (€1032 for the first day and €829 for additional days), operation theatre costs (€461 start up and €7,36 per minute) and day care admission costs for methotrexate treatment for persistent trophoblast (€711). | 4076 | 3645 | 431 | 249 | 624 | 48.852 (−213 473 to 138 799) |

| 2* | Thirty per cent lower ward admission costs (€556 for the first day and €447 for additional days), operation theatre costs (€249 start up and €4,0 per minute) and day care admission costs for methotrexate treatment for persistent trophoblast (€383). | 2562 | 2270 | 292 | 166 | 430 | 33 113 (−2 146 449 to 118 570) |

| Scenario analyses | |||||||

| Model | Scenario | Salpingotomy | Salpingectomy | Diff | 95% CI# | ICER (95% CI#) | |

| 3* | Surgery in day care admission (€251), instead of ward admission until operation theatre available.^ | 2052 | 1754 | 297 | 169 | 437 | 33 730 (−149 544 to 124 372) |

| 4* | Replace disposable bipolar cutting forceps (€343) by re-usable bipolar forceps and re-usable scissors at no costs. | 3250 | 2615 | 636 | 478 | 798 | 72 097 (−234 791 to 204 129) |

| 5* | Replace weekly serum hCG follow-up after salpingotomy by one serum hCG measurement and no further follow-up if decline is according to serum hCG clearance curve. No serum hCG measurement after salpingectomy. | 3152 | 2912 | 240 | 100 | 381 | 27 264 (−92 252 to 109 817 |

| 6* | Replace weekly serum hCG follow-up by a home urinary pregnancy test 6 weeks after salpingotomy at no costs for home pregnancy test. No serum hCG measurement after salpingectomy. | 3077 | 2912 | 165 | 12 | 316 | 18 730 (−52 205 to 83 594) |

| Univariate sensitivity analyses . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model . | Description . | Salpingotomy . | Salpingectomy . | Diff . | 95% CI# . | ICER (95% CI#) . | |

| 0 | Base case | 3319 | 2958 | 361 | 217 | 515 | 40 983 (−130 319 to 145 491) |

| 1* | Thirty per cent higher ward admission costs (€1032 for the first day and €829 for additional days), operation theatre costs (€461 start up and €7,36 per minute) and day care admission costs for methotrexate treatment for persistent trophoblast (€711). | 4076 | 3645 | 431 | 249 | 624 | 48.852 (−213 473 to 138 799) |

| 2* | Thirty per cent lower ward admission costs (€556 for the first day and €447 for additional days), operation theatre costs (€249 start up and €4,0 per minute) and day care admission costs for methotrexate treatment for persistent trophoblast (€383). | 2562 | 2270 | 292 | 166 | 430 | 33 113 (−2 146 449 to 118 570) |

| Scenario analyses | |||||||

| Model | Scenario | Salpingotomy | Salpingectomy | Diff | 95% CI# | ICER (95% CI#) | |

| 3* | Surgery in day care admission (€251), instead of ward admission until operation theatre available.^ | 2052 | 1754 | 297 | 169 | 437 | 33 730 (−149 544 to 124 372) |

| 4* | Replace disposable bipolar cutting forceps (€343) by re-usable bipolar forceps and re-usable scissors at no costs. | 3250 | 2615 | 636 | 478 | 798 | 72 097 (−234 791 to 204 129) |

| 5* | Replace weekly serum hCG follow-up after salpingotomy by one serum hCG measurement and no further follow-up if decline is according to serum hCG clearance curve. No serum hCG measurement after salpingectomy. | 3152 | 2912 | 240 | 100 | 381 | 27 264 (−92 252 to 109 817 |

| 6* | Replace weekly serum hCG follow-up by a home urinary pregnancy test 6 weeks after salpingotomy at no costs for home pregnancy test. No serum hCG measurement after salpingectomy. | 3077 | 2912 | 165 | 12 | 316 | 18 730 (−52 205 to 83 594) |

*Scenario calculated in both arms.

#Non-parametric confidence interval based on 1000 bootstrap replications.

^Reference Dutch Costing Guideline (Hakkaart-van Roijen et al., 2010).

We compared admission the next day in the surgery in day-care unit (€251 per day) with immediate hospital admission and waiting for an operation room to become available (model 3). This scenario decreased the mean costs in both groups.

For salpingectomy, disposable cutting forceps or similar devices were used for convenience but at higher costs. In model 4 we compared the use of the least expensive cutting forceps with the scenario where re-usable instruments were used. In this scenario, the difference would increase to €636 (95% CI €478 to €798), making salpingectomy even less costly.

In model 5, the weekly serum hCG follow-up after salpingotomy was replaced by one serum hCG measurement without further follow-up if the decline in serum hCG was according to the standard serum hCG clearance curve, and without serum hCG measurement after salpingectomy. In this scenario, the mean difference would decrease to €240 (95% CI €100 to €381). In the scenario with replacement of the weekly serum hCG follow-up with a home urinary pregnancy test 6 weeks after salpingotomy at no costs for the home pregnancy test and without serum hCG measurement after salpingectomy (model 6), the mean difference would further decrease to €165 (95% CI 12–316).

Discussion

This study assessed the cost-effectiveness of salpingotomy versus salpingectomy in women with tubal pregnancy and a healthy contralateral tube until an ongoing pregnancy by natural conception occurred within a time horizon of 36 months. The mean direct medical costs were significantly higher for women assigned to salpingotomy compared with salpingectomy. The cost difference was mostly explained by higher costs per woman for initial surgery (€89), re-admissions (€77), persistent trophoblast (€131) and repeat ectopic pregnancy (€62) after salpingotomy. In six scenarios salpingectomy remained less costly, with a scenario without scrupulous post-operative serum hCG follow-up leading to the smallest cost difference between the two treatment interventions (€165, 95% CI €12 to €316). Although there was a small but non-significant health gain of more ongoing pregnancies after salpingotomy, this intervention was not cost-effective (ICER €40 983, 95% CI −€130 319 to €145 491) neither in the base case, nor in six alternative scenarios.

This economic evaluation was based on the cost structure of one university hospital in The Netherlands. We limited the economic evaluation to a hospital perspective in which only health costs were taken into account. Indirect costs such as the value of lost productivity from time off work due to illness were not included. It is possible that costs of salpingotomy and salpingectomy differ between countries and therefore our results cannot unconditionally be generalized to all circumstances. However, since the sensitivity analyses on costs for the admission and operating theatre (model 1 and 2) show no differences in the outcomes, we believe our results should be applicable to other hospitals or countries with a higher or lower cost level.

In our study, the duration of hospital admission was calculated in days from the date of surgery until the day of hospital discharge instead of admission hours. This approach shows a skewed distribution of the duration of admission, but is realistic for the cost calculation in The Netherlands: hospital admissions are calculated in days, not in hours. If women were admitted and had to wait for an operation room to become available, this delay was not reflected by our analysis, because costs were calculated from time of randomization perioperatively. A scenario to operate women in day care surgery would reduce costs to a great extent, but such a scenario does not make salpingotomy cost-effective.

The higher costs of salpingotomy were mainly caused by the serum hCG monitoring with consultations by telephone and discussing the results. The study protocol prescribed weekly serum hCG monitoring after salpingotomy until an undetectable level was reached and at least one measurement after salpingectomy to be repeated if not undetectable. The number of women who had no or incomplete serum hCG follow-up after salpingectomy was substantial (30%), probably since gynaecologists are aware of the very low chance of persistent trophoblast after salpingectomy and serum hCG monitoring after salpingectomy is not recommended in international guidelines. The scenario analyses with a single serum hCG measurement after salpingotomy and no hCG measurement after salpingectomy, or only a urinary pregnancy test at home after salpingotomy, show that overall costs after both treatments can be diminished, but a—substantially smaller—cost difference still remains in favour of salpingectomy. It is known that some gynaecologists apply a prophylactic dose of Methotrexate immediate post-operatively after salpingotomy to prevent persistent trophoblast. In our cost-effectiveness study, we did perform scenario analyses that resemble the scenario of a prophylactic dose of Methotrexate without the necessity of serum hCG follow-up. In these scenarios we tested whether a reduction or no hCG monitoring (scenario no. 5 and no. 6) would make salpingotomy equally costly, but this was not the case: salpingotomy remained more expensive.

In our study, 20% of women allocated to salpingotomy had a conversion to salpingectomy. This would seem to warrant a discussion on surgical skills. We therefore performed a per- protocol analysis, which included only women who underwent the assigned intervention and found similar point estimates and CIs for the primary outcome. This suggests that even without conversions to salpingectomy a positive effect of salpingotomy on future fertility is unlikely.

Future fertility prospects are also an important issue in the economic evaluation. Costs of the initial treatment of tubal pregnancy should be weighed against costs of future infertility treatment, e.g. IVF. In the present cost-effectiveness analysis, costs of IVF were not included since this was not part of the ESEP study protocol. The ESEP population was a fertile population and the fertility outcome measures were pregnancies by natural conception.

In a previous cohort study, we calculated that salpingotomy became cost-effective compared with salpingectomy with subsequent IVF, if the ongoing pregnancy rate by natural conception after salpingotomy was >2.2% higher (absolute risk difference) than after salpingectomy (Mol et al., 1997). The ESEP trial was not powered to detect such a small difference, which would require a huge sample size. In our study, follow-up ended in 5% of women (23/446) because they started IVF within 3 years after surgery: 7% (15/215) allocated salpingotomy and 3% (8/231) allocated salpingectomy.

This study is the first economic analysis that prospectively compared salpingotomy with salpingectomy alongside a randomized trial. A smaller trial was published and found similar results regarding fertility outcome after salpingotomy and salpingectomy, but did not report on the financial costs (Fernandez et al., 2013). Our analysis showed it might be possible that salpingotomy is a cost-effective alternative. For example, at a willingness-to-pay of €45 000, the chance of salpingotomy to be cost-effective is 48% and at a willingness-to-pay of €135 000, the chance is 55%. Based on this relative low chance at a high willingness-to-pay we feel that salpingectomy should be the preferred surgical intervention for women with a tubal pregnancy and a healthy contralateral tube. Our advice for salpingectomy is supported by its favourable short-term outcome in terms of primary treatment success, its lower costs, and in the absence of any significant negative effect on future ongoing pregnancy rates. This conclusion is supported by the results of our patient preference study that showed a strong preference of women towards salpingectomy (van Mello et al., 2010). Instead of future pregnancy prospects being the most important decisive factor, women preferred to reduce the risk of repeat ectopic pregnancy. The development of tools to enhance ‘shared decision-making’ should be further explored to provide patient centred care. Whether salpingotomy should be offered depends on society's willingness to pay for an additional child.

In summary, it can be concluded that the mean treatment costs until an ongoing pregnancy by natural conception in women with a healthy contralateral tube, are significantly higher after salpingotomy compared with salpingectomy without a significant benefit in ongoing pregnancy rates. As unit costs were estimated using Dutch reference prices and cost calculations were based on the practice in The Netherlands, country-specific prices and assumptions need to be considered before generalizing these results to other countries.

Authors' roles

F.M., A.S., W.M.A., B.W.M., F.v.d.V., P.J.H. designed the trial. F.M., N.M.v.M., A.S., D.J., K.T.B., T.M.Y. coordinated the trial. J.A.R., H.R.V., P.G. and C.A.K. collected the data. F.M. and M.v.W. analysed the data. F.M. drafted the paper. All authors interpreted the data, revised the article, and approved the final version. F.M., B.W.M., F.v.d.V., P.J.H. and M.v.W. had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw grants 92003328 and 90700154) and from The Health & Medical Care Committee of the Region Västra Götaland, Sweden.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the women who participated in the trial. We thank the gynaecologists and research nurses of the hospitals of the European Surgery in Ectopic Pregnancy study group for their dedication and assistance.

Appendix

In addition to the authors, the members of the ESEP study group were:

Ineke C. A. H. Janssen, M.D. Ph.D. (Groene Hart Hospital, Gouda), Harry Kragt, M.D., Ph.D. (Reinier de Graaf Hospital, Delft), Annemieke Hoek, M.D., Ph.D. (University Medical Centre Groningen, University of Groningen), Trudy C. M. Trimbos-Kemper, M.D., Ph.D. (Leiden University Medical Centre), Frank J. M. Broekmans, M.D., Ph.D. (Utrecht University Medical Centre), Wim N. P. Willemsen, M.D., PhD. (University Medical Centre Nijmegen, St. Radboud), A. B. Dijkman, M.D. (Boven IJ Hospital, Amsterdam), A. L. Thurkow, M.D. (St.Lucas/Andreas Hospital, Amsterdam), H. J. H. M. van Dessel, M.D., Ph.D. (Twee Steden Hospital, Tilburg), P. J. Q. van der Linden, M.D., Ph.D. (Deventer Hospital, Deventer), F. W. Bouwmeester, M.D. (Waterland Hospital, Purmerend), G. J. E. Oosterhuis, M.D., Ph.D. (Medical Spectrum Twente, Enschede), J. J. van Beek, M.D., Ph.D. (VieCuri Medical Centre, Venlo), M. H. Emanuel, M.D., Ph.D. (Spaarne Hospital, Hoofddorp), H. Visser, M.D. (Ter Gooi Hospital, Blaricum), J. P. R. Doornbos, M.D., Ph.D. (Zaans Medical Centre, Zaandam), P. J. M. Pernet, M.D. (Kennemer Gasthuis, Haarlem), J. Friederich, M.D. (Gemini Hospital, Den Helder)—all in The Netherlands.

Karin Strandell, M.D. (Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Göteborg), Lars Hogström, M.D. (Skaraborg Hospital, Skövde), Ingmar Klinte, M.D. (NU Hospital Group, Trollhättan), F. Pettersson M.D., Ph.D. (Halland Hospital, Halmstad), Z. Sabetirad M.D. (Karlstad Central Hospital, Karlstad), K. Nilsson M.D., Ph.D. (Örebro University Hospital, Örebro), G. Tegerstedt M.D., Ph.D. (South General Hospital, Stockholm), J. J. Platz-Christensen, M.D., Ph.D. (NU Hospital Group, Trollhättan)—all in Sweden.

References

Author notes

The ESEP Group members are listed in the Appendix.