-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ula Aleksandra Kos, Signalling in European Rule of Law Cases: Hungary and Poland as Case Studies, Human Rights Law Review, Volume 23, Issue 4, December 2023, ngad035, https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngad035

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The paper explores Hungary and Poland’s compliance signals conveyed during the European rule of law enforcement process and the responses to these signals by the Court of Justice of the EU and the European Court of Human Rights as judicial organs and the European Commission and the Committee of Ministers as organs supervising compliance. After both states turned illiberal European institutions began condemning the condition of rule of law in both states. Yet, their endeavour—as evident from measures imposed upon Poland, but not Hungary—appears inconsistent. The paper ascribes this to states' differing expressions of commitment to comply with rule-of-law-related rulings as signalled during supervision. It argues that Hungary’s signalled conciliatory attitude compared to Poland’s overt defiance invites more deference from the European institutions and concludes that conveying conciliatory signals in the process of compliance may be used to influence the course and, ultimately, the success of rule of law enforcement.

1. INTRODUCTION

In 2015, when Poland, as the second European Union state after Hungary, set out to become an illiberal regime, the two highest watchdog mechanisms in Europe—the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR)—both had to clarify their positions with respect to the rule of law. Even though the two courts seem to have joined efforts in condemning the deterioration of rule of law situations in both states, the impact of their rulings aimed at redressing the situation remains unclear and uncertain.

The reason behind this, as the paper argues, lies not only in Hungary and Poland’s non-compliance with the European courts’ rulings but also in the two states influencing whether and how these judgements are enforced at the domestic level. For instance, even though Hungary is often thought of as the leader of illiberal resistance against the European institutions, the CJEU has so far imposed the notorious 1 million EUR daily penalty only against Poland.1 Similarly, whilst Poland’s judicial reforms continue to give rise to new adverse ECtHR rulings and urgent interim measures, Hungary somehow seems to be avoiding both, irrespective of the state advancing (but never rectifying) similar reforms. This showcases that the European institutions treat the two states differently and that in this respect, Hungary seems to be in a better position.

This differential treatment, the paper finds, pertains to the two states’ differing compliance strategies employed in the process of compliance. Namely, as Hungary seems to portray a rather conciliatory approach in this regard through avoidance of an overt conflict, its behaviour limits frequent interventions by European institutions. Poland, on the other hand, continues to confront these institutions, allowing them to react more often, and, as indicated above, also by employing more severe tools. Based on this, the paper shows how these responses of European institutions are limited or triggered by different signals of commitment to compliance that the two states convey, showcasing that they play an important role in how the two states are treated. From this, the paper concludes that through signalling, some states might in fact be placed in positions where they may affect the (success of) rule of law enforcement.

Building on the signalling theory from international relations, the paper addresses issues of compliance with international courts’ rulings. In this respect, it investigates whether and how some (illiberal) states may benefit from employing other strategies than overt non-compliance to convey messages of commitment to second-order compliance. In particular, by comparing examples of Hungary and Poland’s behaviour following the decisions of the ECtHR and CJEU, I show how pursuing different compliance strategies matters for influencing judicial behaviour in the area of the rule of law enforcement.

The paper diverges from typical compliance studies that place international courts in control of this process and argues instead that it is, in fact, predominately driven by states as agents conveying signals.2 To support the argument, the paper empirically identifies Hungary and Poland’s differing signals to both European courts and maps out how these institutions respond to the signals as judicial organs and as organs supervising compliance, through the European Commission (Commission) and the Committee of Ministers (Committee). In this context, I investigate the judicial and supervisory (extrajudicial) responses that these institutions employ to enforce the rule of law. Compared to traditional compliance literature, the paper therefore combines how states behave and how courts respond and ties the two behaviours together, thus bringing together two types of compliance literature.

The paper develops the argument in four parts. The first part anchors the argument in the theoretical frameworks of signalling, compliance and judicial behaviour. The second part illuminates the attitude of Hungary and Poland towards the rule-of-law-related CJEU decisions, noting Hungary’s generally more conciliatory approach compared to Poland’s defiance. Third, by employing an original database of ECtHR rulings against the two states, the paper sheds light on Hungary’s avoidance and Poland’s defiance, the two different strategies that the states developed before the Strasbourg Court. Last, the paper then empirically maps this feedback loop and its implications for CJEU and ECtHR’s judicial and supervisory responses. After comparing which institutional responses Hungary and Poland’s behaviour triggers, the paper concludes.

Before proceeding, a preliminary note seems fit. The paper understands enforcement as bringing about second-order compliance with the adverse CJEU and ECtHR judgments.3 In this regard, the selected judgments categorized as rule-of-law-related follow the understanding of the notion by the Commission, encompassing its thick and thin concepts.4 Although in this respect the analysis predominately focuses on the thin concept of the rule of law, i.e. judgments related to the functioning of states’ justice, electoral and constitutional systems and equality before the law, the current rule of law deficit in the two respective states often links the two concepts. This inevitably demands the paper to also touch upon human rights violations of minorities and other vulnerable groups.5 Accordingly, the paper primarily focuses on Hungary and Poland’s compliance strategies employed in their CJEU’s and ECtHR’s rule-of-law-related rulings. Whilst in this respect the extensive existing scholarly research allows a reliable identification of the two states’ CJEU compliance strategies, much less has been studied in this area for the ECtHR. This is especially the case in Hungary, which has thus far faced only two ECtHR cases that fall into the category of rule-of-law-related as defined above. For this reason, the last sections of the paper add a comprehensive empirical study of ECtHR rule-of-law-related decisions and beyond. This study of 2828 decisions seeks to illuminate fully the two states’ ECtHR compliance processes and, indeed, depict how these apply and unfold also in rule-of-law-related matters.

2. SIGNALLING AS THE TRIGGER AND LIMITATION OF EUROPEAN COURTS' RESPONSES

Signalling generally relates to a type of behaviour that conveys information to an (external) audience about the sender.6 As part of reputational theories, the notion typically pertains to states acting affirmatively to reflect adherence to their commitments (i.e. indicating willingness to comply) instead of merely avoiding non-compliance.7 This active, positive behaviour for states means that other states would be more inclined to cooperate with them.8 Typically, states would seek to depict a positive image of themselves. Yet, as scholars find states may—depending on their interests—wish to portray themselves differently. Indeed, this might minimise their international cooperation opportunities, but it can instil their (often autocratic) governments with domestic legitimacy and even deter potential political opposition movements.9

It is important to note that international institutions depend on signalling only where they have limited access to the information on what is actually taking place on the ground, within the states.10 On the opposite, if these institutions had perfect knowledge, signalling would not matter—they could simply access the necessary information instead of relying on states to provide it. Yet, because we often think of states’ compliance processes as proverbial black boxes, (supervisory) international institutions only have limited knowledge about states’ actual courses of action.11 This makes signalling an important tool for discerning states’ past, current and intended actions, which, in combination with compliance studies, also makes it a fruitful area for research.

Since states may control the conveyed messages, this also means that they can contribute to building their own reputations.12 Yet, although these reputations are thought to help external audiences anticipate states’ future courses of action based on their past behaviour, scholars also note that this field is empirically understudied, casting doubt on whether reputation matters at all.13 Furthermore, the scarce existing studies in this respect predominately focus on the state perspective,14 whilst there are only a few studies investigating whether and how signals affect the reactions of the audience.15 Understanding fully the importance of reputation both for senders and recipients of signals that construe it thus requires further empirical studies, aiming to illuminate both sides. To help fill in this gap, the paper maps out the particular responses of the European courts, employed after Hungary and Poland revealed their compliance strategies in the process of the rule of law enforcement. The paper aims to avoid the trap of finding too quickly evidence of causation between states’ signals and audiences’ behaviour.16 Instead, I place emphasis on the sequential game of events.17

As Karen Alter has shown in her studies of the action–reaction relationship between states and international institutions, the European courts are thought to be autonomous and independent actors, free from states’ political constraints.18 Yet, because they necessarily depend on state signals in the process of compliance, I argue that states may nevertheless influence their responses. In particular, as second-order compliance is no longer perceived as binary, but instead ranges on a spectrum from full compliance to non-compliance, courts and their supervisory organs are tasked with detecting non-compliance to justify their interventions. This non-compliance may at times be notoriously difficult to recognise, especially because in addition to overt non-compliance, it is necessary to discern from states’ tactics also its covert forms.

This seems straightforward in cases of overt non-compliance where scholars find that courts’ reactions have even been stimulated by states’ defiance.19 Cases of covert non-compliance, on the other hand, have not only been notoriously difficult to detect but also even harder to address. The issue lies in that here, unlike with obvious defiance, states may act as though they are in fact willing to comply and even make visible efforts towards this end. Although their goal might not be to obey but instead to conceal non-compliance, signals of this kind may, especially if states offer tangible evidence (e.g. adopt formalistic legislation), imitate actual compliance. Furthermore, even if the external audience remains sceptical, such signals are inherently ambiguous.20 This requires international institutions to pinpoint those signals indicating unwillingness to comply and categorize them as non-compliance, because only these signals can adequately justify a response. If, however, the signals are unclear, the institution may be reluctant to act. Given the legitimacy objections raised at international institutions and the inherent ambiguousness of the states’ behaviour,21 the institutions may choose to give the state the benefit of the doubt and not reach for the most interventionist response.

Outside the context of signalling, several scholars have already investigated how in particular the CJEU and the ECtHR (re)act in this respect. Andreas Hoffman, for instance, notes that in anticipation of potential resistance, the CJEU generally practices restraint as long as member states remain committed to the rule of law.22 Even in cases concerning the rule of law, Salvatore Caserta and Pola Cebulak argue that the CJEU remains careful and interferes only very gradually.23 In the same vein, others note that the ECtHR also responds to state strategies and has pursued several tactics to increase compliance.24 Yet, Erik Voeten finds that generally, its course of action is limited due to governments’ capability to influence the implications of judgements through non-compliance.25 To respond to the issue, the ECtHR has developed different tactics. Scholars in this respect describe the so-called variable geometry, finding that the Strasbourg Court responds to backlash with deference and leeway when it comes from consolidated democracies of the European West but not from the East.26 This, they argue, is because compared to their less-liberal counterparts, liberal states are presumed to act in good faith. On the other hand, Başak Çali finds that the Strasbourg Court has also reacted to the presumed less-liberal or even authoritarian states of the European East, but its efforts to take a firm position with respect to autocratic state strategies have been ‘piecemeal, fragmented and contested’.27

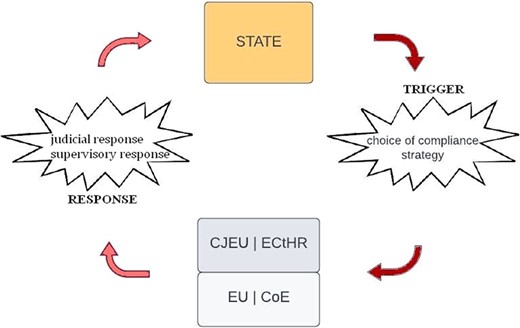

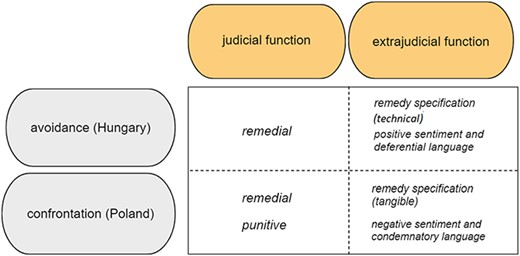

Several conclusions may be drawn from this. First, although inconsistently, both European courts generally respond to state compliance strategies. Second, in their responses, both courts seem to have accommodated for the differences between states, which is most noticeable in their contrasting treatment of Western consolidated democracies and their Eastern less-liberal counterparts. Third, this differentiation occurred precisely because states seem to be employing differing compliance strategies that signal varying levels of anticipated commitment to compliance. All this considered, it is not unreasonable to expect both European courts to respond and adapt also to the differing compliance strategies of Hungary and Poland. Yet, as the two states’ signals differ, the European courts are faced with different inputs acting as feedback loops for activation of their responses. For example, if Hungary is deemed more willing to comply due to its signalled (but not necessarily also intended) efforts, one would expect the institutions to be more deferential, thereby limiting frequent and more serious interventions against the state. On the other hand, Poland’s openly expressed intention not to comply would be expected to trigger all interventions in the toolbox to achieve compliance. Accordingly, it may be argued that the responses of both European courts and actions to enforcing rule-of-law-decisions are sensitive to state signals conveyed through compliance strategies they choose to pursue. This argument is schematically depicted in Figure 1 below.

Feedback loop between compliance strategies and institutional responses.

The next sections explore this empirically by first identifying the nature of the conveyed signals through a deconstruction of Hungary and Poland’s compliance strategies before the two European courts. After illustrating how the two states signal their general approach to compliance, the paper next maps out the particular functions of European institutions responding to these signals. From this, I then discern that signals influence the European courts’ exercise of their functions and that in this way, the two states may affect the rule of law enforcement.

3. RESISTANCE AGAINST THE LUXEMBOURG COURT

After Fidesz’s right-wing coalition obtained a parliamentary two-thirds majority in Hungary in 2010 and when five years later, the conservative Law and Justice party (PiS) secured an absolute majority in the Polish parliament, the new governments set to significantly change the states’ apparatuses.28 This most notoriously resonated in the executives of the two countries capturing states’ legislative and judiciary branches.29 If the two young democracies initially embraced the democratic and liberal values of the EU and the CJEU, their illiberal governments now rejected them, causing friction with the institutions.30 The EU and consequently the CJEU, however, responded only gradually. The Commission initially addressed the issue by triggering infringement proceedings before the CJEU under Articles 258–260 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). This was later followed by a parallel—inherently more political—procedure under Article 7 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), also known as the ‘nuclear option’. Most recently, the rule of law deficits in Hungary and Poland prompted the EU to introduce the rule of law (conditionality) mechanism. As described in more detail below, these actions to protect the rule of law prompted different reactions from the two states.

A. Hungary: The Constitutional Court De-Escalates the Conflict

Hungary’s change of attitude towards the CJEU was gradual. In the beginning, the government perceived the Commission’s infringement procedures as ‘a chance for dialogue and an opportunity to resolve conflicts’ between the state and the EU.31 For instance, after it became clear that the Commission and Hungary’s views on the infringement procedure for lowering the retirement age for Hungarian judges diverged, the CJEU in C-286/12 Commission v Hungary of 6 November 2012 found that the domestic legislation was discriminatory, but not (yet) an issue of judicial independence.32 Following the ruling, the Hungarian government assured that the state takes no issue with the EU, emphasizing that it agrees with its fundamental principles and common European values, including by itself stressing the importance of the independent judiciary.33 In this vein, the state promised to comply with the ruling, which it later fulfilled by changing domestic legislation and offering financial compensation.34 Although scholars warn that Hungary’s compliance was merely illusory as the formalistic amendments proved to be ineffective in practice,35 this illustrates how, at least in the first years after the new government came into power, Hungary’s approach towards the CJEU was conciliatory rather than inviting conflict.

After 2015, i.e. after the peak of the refugee crisis in Europe, Hungary’s attitude radically shifted. The government used the infringement proceedings initiated because of its migration policy to blame the EU and the CJEU for leading foreign ‘political attacks’ on Hungary as punishment for its resistance to the ‘migrant business’, as any type of aid to asylum-seekers was termed.36 This attitude ultimately reflected in Hungary adopting legislation to curb the functioning of domestic non-governmental organizations (NGOs), re-organize the higher education sector and criminalize assistance to asylum-seekers. This gave rise to several infringement proceedings that, following the government’s loud criticism of the EU and refusal to comply,37 resulted in CJEU finding Hungary in breach of its EU obligations.38 In reaction, the state adopted some perfunctory measures.39 Even today, the government urges to stop migration to Europe and maintains all measures directly or indirectly related to curbing it.40

Meanwhile, whilst the government (and later also the judiciary)41 challenged the CJEU and its authority, the Hungarian Constitutional Court, surprisingly, took a more neutral position. After the Commission referred Hungary to the CJEU following unsuccessful infringement proceedings related to the state’s rules and practice in transit asylum zones at the Serbian–Hungarian border, the Luxembourg Court in C-808/18 Commission v Hungary of 17 December 2020 found Hungary’s legislation in breach of the EU law. To secure a legal basis for leaving the state’s asylum system intact irrespective of the ruling, Hungary’s Minister of Justice brought the case before the Constitutional Court. The court was asked to review the compatibility of the CJEU ruling with the Hungarian Fundamental Law, thereby also being implicitly asked to question the primacy of the EU law.42 In its decision of December 2021, the Constitutional Court in large part sought to favour the government.43 Yet, and more importantly, the court concluded that the review before it cannot lead to the ‘examination of the primacy of the EU law’,44 thereby refusing to pick a side in the heated EU–Hungary conflict. Indeed, the Constitutional Court not only refused to condemn the government’s asylum policy but also avoided a direct (and further) conflict with the CJEU. This seems to have de-escalated a growing conflict with the institution, since—even though the Commission asked the CJEU to impose monetary sanctions more than a year ago—the fine has not yet been imposed.45

B. Poland: Constitutional Tribunal at the Fore of Defiance

If Hungary’s resistance to the CJEU’s rulings evolved gradually, Poland, on the other hand, engaged in conflict with the Luxembourg Court soon after PiS came into power in 2015. In this respect, the conflict gained momentum after the new government managed to capture the Constitutional Tribunal as early as December 2016 by influencing its composition.46 During this process of changing the state’s judiciary, the Commission noted that the government in the period of just two years adopted ‘laws affecting the entire structure of the justice system in Poland’.47 These reforms gave rise to several infringement proceedings.48

Following the first infringement proceedings, the CJEU found breaches of judicial independence in the lowered retirement age regime of Polish judges.49 In response, scholars note that the state defied compliance by actively seeking to ‘further capture the judiciary from within’.50 In particular, this reflected in Poland continuing to illegally appoint new judges and facilitating the functioning of the two new Supreme Court bodies, the Disciplinary Chamber and the Extraordinary Control and Public Affairs, established in 2017.51 Poland’s refusal to cease their functioning was key for a further escalation of the state’s conflict with the CJEU.52

The operation of the Disciplinary Chamber was first subject to CJEU’s interim order of 8 April 2020.53 This was followed by C-791/19, Commission v Poland of 15 July 2021, where the CJEU decided that the disciplinary regime does not comply with the requirements of judicial independence and as such breaches EU obligations.54 In reaction, Poland criticized the ruling as an undue interference of the EU overstepping its competences, which further facilitated the disciplining of domestic judges.55 In this respect, a significant role in escalating the conflict was played by the Polish Constitutional Tribunal, which, unlike the Hungarian Constitutional Court, confronted the CJEU by strongly defending the position of the Polish government. Accordingly, the Polish Constitutional Tribunal declared the 2020 interim order ultra vires, finding also that all other CJEU interim measures are unconstitutional insofar as they address the organization of Polish courts.56

The conflict continued with another CJEU’s order for interim measures, demanding that Poland prevents the Disciplinary Chamber from functioning altogether.57 This prompted the Polish Prime Minister to again assemble the Constitutional Tribunal, which, in a decision K3/21 of 7 October 2021, decided that the EU law is incompatible with the Polish Constitution insofar as it allows domestic judges to review the independence of their peers or the legality of judicial appointments.58 In effect, this meant that the CJEU was no longer competent to review the organization of the Polish judiciary. Backed by the domestic ruling, Poland refused to comply with the CJEU’s ruling and its interim measures, although it promised to dismantle the Disciplinary Chamber earlier that year.59 In this respect, the state called the EU out to stop trying ‘by usurpation and blackmail’ gain competences beyond those enshrined in the EU treaties.60 This last clear signal of defiance ultimately prompted the Commission to request the CJEU to order a daily penalty payment, which, in an Order in C-204/21 R, Commission v Poland of 27 October 2021, imposed a daily fine. In response, Poland again turned to the Constitutional Tribunal, asking it to decide whether the CJEU may impose daily financial penalties on the state.61 At the time of writing, it had not yet rendered its decision.

4. HUNGARY'S AVOIDANCE VERSUS POLAND'S DEFIANCE AGAINST THE STRASBOURG COURT

If both states resist the CJEU in some way, this is much less straightforward before the ECtHR. In the eyes of the Strasbourg Court, both states are considered good, even excellent compliers. This is evident from Hungary’s 75 per cent and Poland’s 95 per cent official compliance rates.62 In this regard, the two states do not seem to differ from the rest of Council of Europe (CoE) member states, where the ‘old’ members on average comply with 90 per cent ECtHR rulings, whilst the ‘new’ CoE members (Hungary and Poland included) on average comply with 75 per cent.63 Yet, the first glance may be deceiving. As the paper reveals in this section, states’ compliance rates can be boosted by friendly settlements and unilateral declarations, which allow for easier and faster compliance without requiring any domestic change.64 Given that they represent 50 per cent of Hungary and 42 per cent of Poland’s entire caseloads,65 these alternative instruments may substantially affect their compliance records. In addition, whilst states’ compliance records are an estimation of their general performance, they say little about the actual strategies states employ in the process of compliance. This means we have to look beyond official records, a task the paper approaches empirically.

Whilst the previous section relied on existing qualitative studies of states’ reactions to the CJEU enforcing rule of law, the next two sections turn to mixed methods and identify Hungary and Poland’s approaches before the ECtHR. Although in this respect, both sections focus primarily on the rule-of-law-related ECtHR cases, they add to this a supplementary empirical study of cases also beyond this area. This way, I seek to offer insight into the broader context of Hungary and Poland’s differing compliance processes, which is key to understanding fully how these processes apply and unfold also in their rule-of-law-related matters. The analysis reveals in this respect that the two states’ general compliance strategies apply equally there. Accordingly, the following sections study the two states’ compliance processes by analysing an original database of 1105 adverse ECtHR cases against Hungary and 1723 adverse cases against Poland until the autumn of 2021. The dataset contains several pieces of information collected from HUDOC on each ruling.66 Here, the study first employs descriptive and inferential statistical analysis. I also include a qualitative analysis of all documents on each case published on HUDOC.EXEC, looking at the involvement of different actors, including both states’ governments, their NGOs and the Committee itself. This analysis of information collected from HUDOC is complemented by reports from national legal experts, who collected and interpreted every piece of information we could find on each ECtHR ruling. They looked into public records of Hungary and Poland’s parliamentary sessions and their various committees, state officials’ statements and different ministerial webpages. We also investigated all domestic media outlets that have ever reported on any of the cases, NGO reports and statements and domestic scholarly works. Informed by the findings of the quantitative and qualitative parts, the data on Hungary are supplemented with semi-structured interviews.

A. Hungary’s Avoidance as Covert Defiance

Unlike the CJEU, which avoided delving into judicial independence when faced with a case addressing the decreased retirement age of Hungarian judges in 2012, the ECtHR engaged with the issue in the 2016 Baka case and again in the 2017 Ermenyi case.67 By assessing cases through the lens of judicial independence, the Strasbourg Court found several violations of the European Convention on Human Rights (Convention) in the termination of mandates of the president and the vice-president of the Hungarian Supreme Court.68 In response, Hungary seemed to proceed as usual by paying the just satisfaction award and submitting several reports on planned or adopted remedial measures.69 To further persuade the Committee of Hungary’s sincere dedication to remedy its violation, the Hungarian Minister of Justice even assured that ‘Hungary will fully abide by the Convention requirements’ so as to prevent similar future violations.70 However, regardless of giving such explicit assurances to the Committee, the case is still pending and currently in its eighth year of supervision. According to the NGOs, Hungary took no substantive steps towards implementation and—what is more—the government seems to have simply copied and pasted parts of its previous reports, offering no actual new developments or undertakings.71

The above examples illustrate what the literature describes as disguised non-compliance (also known as symbolic or creative compliance).72 This is one of the strategies that Hungary has employed to avoid compliance with the ECtHR rulings since 2010. These strategies were previously identified by analysing the data collected on Hungary, which revealed significant differences in the state’s behaviour before and after 2010.73 This difference is described in more detail elsewhere but for the purposes of this paper, I highlight its most important findings here. In this context, interviews with domestic NGOs and academia suggest that Hungary regularly submits to the Committee copy-pasted reports about old and already adopted measures and reports that often include perfunctory formalistic legislation adopted to appease the Committee.74 This has been described in the literature as autocratic legalism. By adopting this approach, the state—at least on its face—signals to the international community its commitment to comply with a judgment, when in fact its true intention is to either delay the implementation of the ruling or, more often, avoid implementation altogether.75

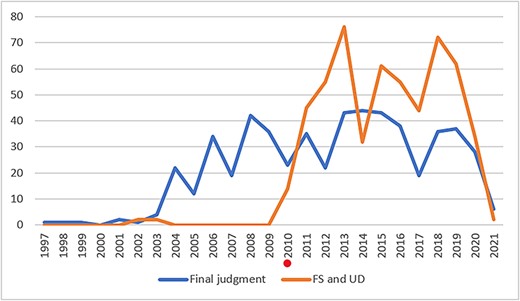

If by disguising non-compliance Hungary seeks to avoid compliance in the short run, the analysis further shows that the state employs another strategy aimed at avoiding ECtHR adjudication altogether. According to my previous study,76 Hungary significantly increased its use of friendly settlements and unilateral declarations as alternatives to Strasbourg Court proceedings after 2010. Today, these instruments correspond to 50 per cent of its cases before the ECtHR, but have in the past already encompassed more than 70 per cent of its entire caseload. If this at first seems like a legitimate practice for resolving repetitive cases, the extent of the practice in Hungary is problematic. Namely, if we consider the number of all individual applications that ended up joined in settlements, previous analysis reveals that this number by five times surpasses the number of all adverse judgments ever rendered against Hungary in ECtHR proceedings. The practice seems problematic also from a comparative perspective. Studies show that other new CoE members settle up to 24 per cent of their cases whilst the old members settle only 8 per cent.77 In fact, several states do so only exceptionally.78 In this respect, Hungary is at the very top among the most frequent settlers and is surpassed only by North Macedonia and Serbia.79

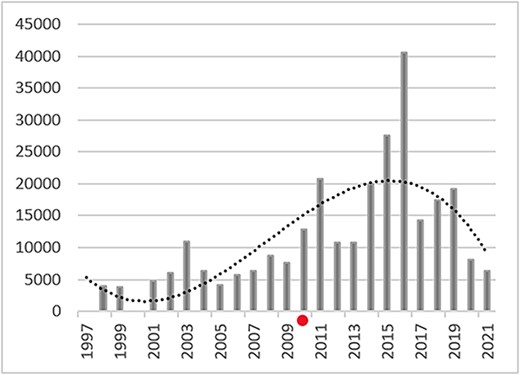

The frequency of the use of alternative instruments is depicted in Figure 2 below. The graph shows how alternative instruments in Hungary (orange line) in 2010 (marked by a red dot) surpassed the share of rulings rendered in ECtHR proceedings (blue line).

Alternative instruments surpassing regular ECtHR proceedings after 2010.

In this respect, scholars warn against the misuse of alternative instruments.80 Accordingly, settlement allows states to minimise the effect of the ECtHR rulings domestically and, by halting applicants’ petitions, hide substantive systemic domestic issues that would otherwise lead to important precedent-setting judgments.81 These instruments also improve states’ compliance rates as they usually do not require a promise of any other remedies. Furthermore, as alternative instruments can hardly be rejected by victims, this prevents them from bringing complaints before the Strasbourg Court.82 As they get struck out, this allows states to make their violations disappear from their official records.

From this, it is apparent that Hungary, rather than entering into a conflict with the ECtHR, seeks strategies to avoid confrontation. Although such strategies on their face seem less harmful to the Strasbourg Court compared to vocal criticism, such subtle pushback can in the long run affect its authority, diminish the domestic impact of its judgments and dissuade potential applicants from entrusting it with their case.

B. Poland’s Overt Defiance

In contrast to Hungary employing its covert strategies of avoidance since 2010, Poland seems to have taken no obvious rule-of-law-related issue with the ECtHR until 2021, when the court for the first time addressed its judiciary reforms. In the 2021 Xero Flor case,83 the ECtHR decided that the captured Polish Constitutional Tribunal (that ruled on the contested case in 2017) cannot be regarded as a ‘court established by law’.84 Accordingly, if an illegally appointed judge participated in deciding on their case, any person’s right to fair trial under Article 6 of the Convention has been violated.85 In response, several Polish officials, including the president of the Constitutional Tribunal proclaimed the ruling as a ‘non-existing judgment’ due to its unlawful intervention in the sovereignty of Poland, falling outside the competence of the ECtHR.86 This led the Polish Prosecutor General to follow Poland’s approach towards the CJEU and lodge a motion to the Constitutional Tribunal, demanding it to declare the ECtHR’s interpretation of the Convention incompatible with the Polish Constitution.87 On 24 November 2021, the Tribunal indeed issued a ruling in K 6/21 where it decided that Article 6 of the Convention was incompatible with the Constitution insofar as it confers on the ECtHR the competence to review the legality of appointments to the Constitutional Tribunal.88 The Tribunal, more precisely, considered the ECtHR ruling to ‘demonstrate a lack of knowledge of the Polish legal system’ and as unduly interfering with it.89 Accordingly, it announced that the ruling was a ‘non-existent judgment’ for the purposes of Polish law.90

Following Xero Flor, the ECtHR furthermore addressed Poland’s issues of premature termination of judges’ mandates (Broda and Bojara 2021), issues related to a biased disciplinary procedure (Reczkowicz and Dolinska-Ficek and Ozimek 2021) and a lack of independence of an appellate body in judicial appointment proceedings (Advance Pharma sp. z.o.o 2022).91 In response, the Polish authorities accused the ECtHR of discriminatorily favouring the old CoE members over the new members like Poland and, in particular, seeking to destabilize the state’s judiciary.92 They referred to the rulings as ‘politically motivated’ and lacking a legal basis, which implied that the rule-of-law-related rulings of the ECtHR would share the same fate as the rule-of-law-related CJEU judgments.93 This has recently been confirmed by the state’s explicit statement to the Strasbourg Court’s Registry that Poland will not comply with any of the ECtHR’s interim measures concerning the Polish judiciary, the numbers of which are accumulating in the court’s docket by the day.94

Surprisingly however, and in contrast to this confrontational attitude following ECtHR’s post-2021 rule-of-law-related rulings, a closer look into Poland’s ECtHR case law reveals that the state generally takes no apparent issue with the Strasbourg Court.95 The analysis shows that the 2015 illiberal shift seemingly had no effect on Poland’s ECtHR compliance. In fact, its general compliance rate actually improved: if the state complied with 64 per cent of its cases before 2015,96 the share of closed cases improved after that year, rising to 81 per cent.97 Today, this amounts to 95 per cent compliance with the ECtHR rulings, including 78 per cent of leading cases.98 To implement the ECtHR judgments, the state holds quarterly meetings of the Inter-ministerial Team for the ECtHR under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (the body responsible for coordination of implementation of ECtHR judgments)99 and maintains a dialogue with the institution by regularly submitting reports on planned or adopted remedies to the Committee.

In this respect, Poland has so far paid compensation after virtually every rendered case where compensation was awarded.100 Interestingly, this applies also to the contested cases of Xero Flor, Broda and Bojara and Reczkowicz. These compensation payments are surprising. Why would a state that considers ECtHR rulings as ‘non-existent’ nevertheless pay out damages? Though going into detail exceeds this paper, there generally is a rationale behind states executing payments whilst refusing to engage in any further domestic change. The most obvious is that the typically very low compensation awards before the ECtHR are not and have never been an issue for states.101 Because other remedies require more onerous interventions, states are generally more inclined to pay out damages than to take a more substantive course of action. Furthermore, as noted by Veronika Fikfak, states may perceive damages as ‘cost of their violations’.102 As long as victims are compensated, so the argument goes, states get an ‘easy way out’ without having to stop the practice that gave rise to ECtHR proceedings in the first place. Related to this is the last argument that having complied at least in part reduces the reputational and political pressure for states of full non-compliance as an alternative.

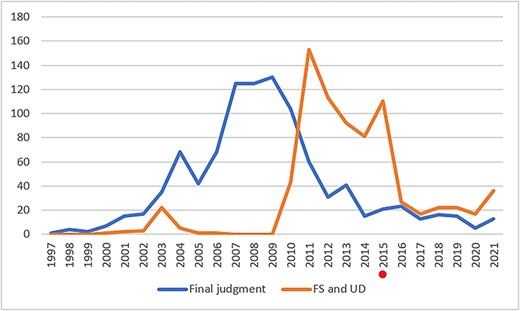

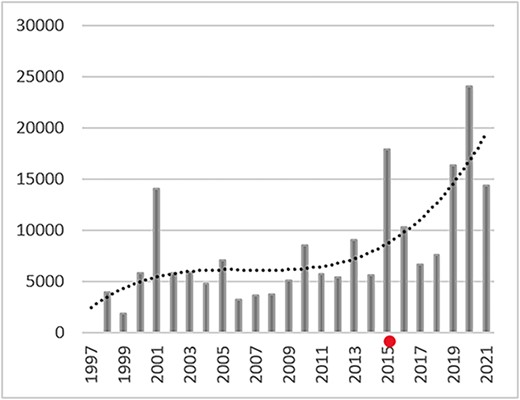

Complementing cases issued in regular ECtHR proceedings, 42 per cent of Poland’s case law results in alternative instruments.103 Yet, their analysis indicates that, unlike Hungary, Poland does not seem to use settlements as a strategy to boost its compliance record. Indeed, Poland began settling more frequently after 2010 when the ECtHR began facilitating the use of alternatives104, but the longitudinal analysis reveals a reversal of this trend. In this respect, Figure 3 below shows that in 2015, the policy of resorting to alternative proceedings decreased (orange line, 2015 is marked by a red dot) and that since 2015, the frequency of settlement is much lower.

The stark contrast between Poland’s initial and today’s use of alternative instruments is surprising, especially considering the broader context and the very beginnings of their use before the ECtHR. According to Helen Keller, it was precisely Poland, in particular its government agent before the ECtHR who was key in concluding the first-ever pilot-friendly settlements in 2005 Broniowski and 2008 Hutten-Czapska cases.105 The idea was to include in one pilot settlement several similar applications in cases with established case law and unburden the Strasbourg Court as well as the state of future repetitive cases. After the initial success of such settlements in Poland, the agent proposed to CoE to begin facilitating their use among other member states.106 This initial excitement about resorting to alternative instruments is reflected also in my analysis, as depicted by their increased use in the period 2010–15 in Figure 3. This theory does not, however, explain their drop in the subsequent period.

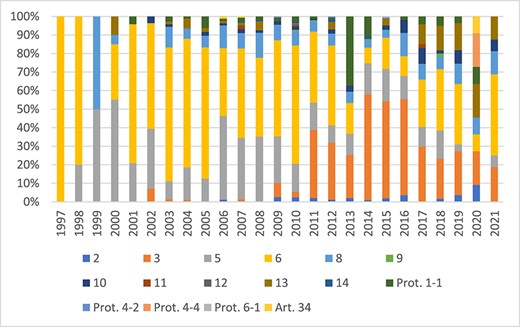

The obvious reason could be a shift in the structure of Poland’s underlying violations, rendering them unfit (or at least falling outside Poland’s usual practice) to settle. Yet, further analysis of the structure of all violations underlying Poland’s case law after 2015 reveals that it remained consistent, thereby diminishing the causal link between a potential change in the structure of violations and the reduced use of alternative instruments. Figure 4 below reveals in this respect that like before 2015, the prevalence of Poland’s post-2015 violations continues to pertain to Articles 3, 6 and 5 of the Convention, which coincides with Poland’s most frequently settled Convention violations included in Articles 3, 6 and 5, respectively.107 In light of the fact that it was Poland’s own idea to facilitate the use of alternative instruments in the first place, this may offer an alternative explanation. It could indicate a shift in the new government’s policy, opting from the initial collaboration with the ECtHR to rather choosing to defend the position of state organs in the Strasbourg Court proceedings and, through that, defending also violations they may have perpetrated.108

5. SIGNALS MATTER. THE IMPLICATIONS OF STATE STRATEGIES FOR JUDICIAL AND EXTRAJUDICIAL FUNCTIONS OF EUROPEAN INSTITUTIONS

In spite of some parallels between Hungary and Poland’s behaviour before the two European courts, the above comparison of their compliance strategies reveals that irrespective of their common shift to illiberalism, the two states behave significantly differently. First, because their Constitutional Courts interpreted the binding force of the Luxembourg Court’s rulings and consequently the primacy of EU law itself differently, Hungary and Poland’s conflict with the institution seems to have taken different courses. Namely, whilst the Polish Constitutional Tribunal’s open confrontation escalated the conflict between the Polish illiberal government and the EU and its CJEU, the seemingly conciliatory approach of Hungary’s Constitutional Court seems to have de-escalated the growing tension between the Hungarian illiberal government and the institution. Second, the two states’ attitudes towards the ECtHR are diametrically opposite: whilst Hungary employs strategies that signal an effort to comply but, in fact, minimizes its engagement with ECtHR judgments or avoids them altogether, Poland recently adopted the same approach as before the CJEU and openly resists the Strasbourg Court. From this, one might generalize that, at least in the context of rule of law enforcement, Hungary seems to be seeking to avoid an overt conflict with the European institutions, whereas Poland is ready for a standoff with the courts and is willing to openly defy international institutions.

In literature, the described compliance strategies affect states’ reputations and signal differing levels of commitment to compliance.109 The following section uses these signals as the basis to map out how both European Courts use differing institutional functions during the compliance processes against Hungary and Poland. I follow the delimitation of international courts’ functions by Caserta and Cebulak who identify courts’ judicial and extrajudicial functions depending on whether they are part of their adjudicatory functions or their broader institutional and political settings. Whilst courts employ judicial functions in the course of their court proceedings, extrajudicial functions are expressed through the inter-institutional dialogue with different organs of regional organizations in which the two European courts are entrenched.110 Based on this, this section describes specific responses to Hungary’s avoidance and Poland’s defiance of the CJEU and the ECtHR as judicial organs on one side and the Commission and Committee as their extrajudicial supervisory organs on the other. The overview of specific institutional functions is included in Figure 5 below.

Map of European institutions’ judicial and extrajudicial functions.

As depicted above, this section argues that Hungary’s avoidance draws a substantially more lenient approach of European institutions, which is reflected in the limited judicial and extrajudicial functions triggered. Unlike in Poland, the European courts have so far only been able to exercise their remedial function in Hungary but not punitive, whereas the extrajudicial function triggered pertains to specifying merely technical demands, accompanied by generally more positive sentiments and more neutral if not deferential language in the supervisory organs’ dialogue with the state. In contrast, Poland’s confrontational attitude triggers and sustains the European courts’ remedial as well as punitive functions, along with triggering more tangible and detailed remedy specification, generally more negative sentiments and condemnatory language from the supervisory organs. In what follows, I explain this in more detail.

A. Judicial Function

Bringing about second-order compliance generally relates to courts’ ability to nudge states into fast and, more importantly, successful implementation of their judgments. This function typically includes the ability to punish non-compliance, which in the case of the two European courts significantly differs. Namely, whilst the CJEU is capable of imposing substantive monetary fines, the ECtHR cannot sanction states and relies on voluntary state compliance. To a degree, states can be incentivized by the political influence of the Committee, which may, once it becomes clear that states refuse to do so, initiate infringement proceedings under Article 46(4) of the Convention. Both the CJEU sanctions and the ECtHR infringement proceedings relate to the punitive functions of the two courts. The Strasbourg Court may, however, adjust its remedies over time to reflect states’ (past) behaviour. For the most part, the approach is remedial in nature. This second, remedial function is analysed first, followed by the punitive function.

(i) Remedial function

Although the ECtHR’s reaction to non-compliance does not entail sanctions, the Strasbourg Court may nevertheless respond to state behaviour by triggering its remedial function. This is first reflected in the prescription of the non-monetary individual or general measures.111 Here, the ECtHR takes it upon itself to determine—either in the main or the operative part of the judgment—the course of remedial measures, instead of leaving this decision to the states as would typically be the case.112

The analysis of remedies awarded by the ECtHR against Hungary and Poland in this respect shows that the Strasbourg Court resorts to prescribing non-monetary remedies significantly less often than to awarding monetary damages. This is in line with the prior research highlighting that the ECtHR prescribes non-monetary remedies only exceptionally.113 Unlike monetary remedies, which are awarded practically in every case against Hungary and Poland,114 the ECtHR has only rarely determined non-monetary remedies, even after 2010 and 2015 when the two illiberal governments came to power.115 The longitudinal analysis in this respect, however, reveals that the use of the ECtHR’s power to require the adoption of specific remedies in both states has enhanced.116 Compared to the previous era where no measures were prescribed, the ECtHR specified remedial measures in four cases after 2010 against Hungary.117 Similarly, the ECtHR prescribed remedial measures in three cases against Poland before 2015, whilst this increased to six cases following that year.118

The second remedial function of the ECtHR relates to adjusting monetary remedies.119 The results of the analysis are depicted in graphs below, depicting chronologically the trend of ECtHR compensations, awarded from 1997 until the autumn of 2021 against Hungary (Figure 6) and Poland (Figure 7).

Average compensation (€) by year Hungary. Trendline: polynomial, order 3.

Average compensation (€) by year Poland. Trendline: polynomial, order 3.

The above first reveals that, much like with non-monetary remedies, the ECtHR over time increased the amounts of damages awarded against both states.120 This increase, however, differs depending on the state involved. Namely, in Hungary, the ECtHR on average awarded roughly 7581 EUR before 2010, while this increased by 160 per cent to roughly 19,649 EUR after that year. In Poland, the Strasbourg Court on average awarded 5754 EUR before 2015, whereas the compensation increased by 100 per cent after that year, settling at an average of 11,484 EUR. Comparing the two states’ pre- and post-illiberal eras, this increase in awarded damages was thus initially higher in Hungary than in Poland. Scholars in this respect describe several factors that may influence the amount of awarded compensations, including the specific state behaviour.121 This could explain the initially more severe approach of the ECtHR against Hungary. Namely, if we recall the two states’ compliance strategies described in the third section, we can note that Hungary decreased its (honest) cooperation with the ECtHR after 2010, whilst Poland after years of almost admirable compliance only recently put its foot down in defiance.

Even though the described increase in damages was at first more substantive in Hungary than in Poland, a closer look at the graphs shows that the ECtHR might have recently reversed the trend. The trendlines (black dotted lines) in this regard indicate that in Hungary, the average damages amount peaked in 2015 but got overturned completely after 2019 when the damages settled back at their pre-2010 level. The trend of increasing damages, however, still persists in Poland. Recalling again the third section, this finding fits the two states’ strategies: whilst Poland’s initial cooperation recently grew into and continues to represent an overt conflict, Hungary over time began engaging in creative compliance, including by replacing ECtHR judgments with alternative settlement proceedings. This seems to have helped it avoid more severe monetary repercussions.

Indeed, the ECtHR seems to have employed and enhanced its (non-monetary and monetary) remedial function against both states after their illiberal shifts. Yet, by focusing on monetary damages, the Strasbourg Court clearly approaches the two states differently and, after the initially more severe response, it seems to have softened its approach towards Hungary, whilst its endeavours continue with respect to Poland.

(ii) Punitive function

The punitive function of the European courts is reflected in the CJEU’s competence to order monetary fines. This procedure unfolds after the Commission has requested a penalty following a state’s non-compliance with a previous Luxembourg Court’s ruling. So far, the CJEU only sanctioned Poland, ordering the state to pay a 1 million EUR daily fine until it complies with its interim measures and until it reverses the illegal disciplinary regime. On the day of writing, the penalty amounts to more than 500 million EUR, and it continues to increase daily.122 In contrast, Hungary has been subject to the Commission’s request for a penalty for its failure to comply with the 2020 case related to transit asylum zones at the Serbian–Hungarian border, but, even more than a year later, the CJEU has not yet decided to sanction the state.123 This delay is striking, and its extent becomes even more obvious if we compare it to Poland where the daily fine was imposed less than two months after the Commission’s referral.124

At the ECtHR, the punitive function in principle relates to the possibility of the Committee initiating infringement proceedings before the Strasbourg Court under Article 46(4) in connection with Article 46(1) of the Convention. The very first such procedure was triggered in 2017 against Azerbaijan following the state’s non-compliance with the notorious Ilgar Mammadov case.125 The second time around, the Committee initiated infringement proceedings in 2022 after Turkey’s refusal to comply with the ECtHR Kavala case.126 Both cases were followed by the Strasbourg Court acknowledging the states’ failure to comply with the original rulings and a declaration that accordingly, they are in violation of Article 46(1) of the Convention, which binds states to abide by and execute ECtHR rulings. Both infringement cases also have in common that they followed a gradually increasing condemnatory language of the Committee, used in its communications with the states. Whilst I elaborate on this in more detail below, I note here that just before deciding to refer Azerbaijan and Turkey back to the ECtHR, the Committee resorted to the use of a specific ‘infringement phrase’. As evident from my analysis of consecutive Committee Decisions following the original Ilgar Mammadov and Kavala cases,127 this phrase refers to states’ obligation under Article 46(1), of the Convention to abide by the final ECtHR judgments and begins appearing after it becomes clear that states might be resisting compliance. In both, Azerbaijan and Turkey, the Committee initially used the phrase to reiterate and emphasize states’ obligation to comply, which in later communications led to the Committee declaring a flagrant breach of Article 46(1), followed by a decision to refer the states to the ECtHR.

This gradual aggravation of the Committee’s language, ultimately paired with the use of the ‘infringement phrase’, arguably signals its intent to initiate the infringement proceedings. In this regard, the same phrase appears in several communications against Poland, including following all cases relating to judicial independence.128 In contrast, it has thus far been used only in two cases against Hungary and even there in its softest form.129 If we rely on the pattern presented in Ilgar Mammadov and Kavala cases, this indicates that Poland might as well already be at the doorstep of the ECtHR infringement proceedings. This, at this point, still seems somewhat of a distant threat for Hungary.

B. Extrajudicial Function

The function of supervising the implementation of CJEU and the ECtHR judgments has been entrusted to the Commission and the Committee. The Commission has so far been very active with respect to the rule of law enforcement in Hungary and Poland. This is most notably reflected in the recently introduced rule of law mechanism, which as an umbrella term encompasses several legal tools aimed at promoting and, if needed, also serves as a tool to intervene in the rule-of-law-related matters within EU member states. Among others, the functions of the Commission in this regard include engaging in dialogue with the states and issuing annual reports, issuing recommendations and specifying the more tangible rule of law milestones, which states need to meet to obtain EU funding. Ultimately, the Commission also has competence to decide to withdraw state funding altogether.

The role of the Committee, on the other hand, is predominately political. In this respect, the supervisory body may resort to political pressure as exerted in its meetings with state representatives. Although these meetings are held in closed sessions, the Committee’s attitude towards states has been detected in the language used in its published communications. This first relates to the general sentiment of the communication and may, as second, also surface in the specification of remedies as a request to the state to undertake a specific course of action by spelling out different obligations. What follows is the analysis of remedy specification and sentiment used by the Commission and the Committee vis-à-vis Hungary and Poland.

(i) Remedy specification

Spelling out specific remedies to address the identified issue is an important tool for steering states into a particular course of desired action, as it narrows down their discretion as to how a situation may be addressed.130 In the EU context, the opportunity for the Commission to specify remedies arises periodically by way of distributing the EU budget. In relation to the rule of law in Hungary and Poland, the Commission froze both states’ post-pandemic-recovery funds as a source of extraordinary EU funding.131 This was further aggravated by the initiation of the more severe rule of law conditionality mechanism against Hungary, due to the fear of the state misusing its regular funding and endangering the regular EU budget.132 To unlock the funding and avoid its ultimate withdrawal, the solution, at least from the EU perspective, seemed pretty straightforward—the Commission (in negotiation with the two states) issued the so-called rule of law (super) milestones, a sort of an ultimatum in the form of a list of requirements that each state must meet. These may extend to several issue areas and may demand various more or less burdensome courses of action.

In particular, the Commission required Hungary to meet 27 super milestones, whilst, in contrast, Poland is requested to fulfil only two. Yet, although their quantity indicates a significantly more severe attitude of the Commission towards Hungary, the content of the milestones—at least in the context of judicial independence and other thin rule of law matters discussed above—reveals a different image. Among Hungary’s 27 super milestones, only four address concerns other than corruption as seemingly most capable of jeopardizing the EU budget. More specifically, these four milestones require Hungary to strengthen the role of the National Judicial Council as the administrative judicial organ, ensure fair future elections of the president of the Supreme Court, remove obstacles for CJEU preliminary references and remove the possibility of the government to challenge domestic judicial decisions before the Constitutional Court.133 Apart from this last requirement, no milestone relates to reversing measures already enforced—even those clearly rushed through by autocratic legalism—by the illiberal government, nor to remedying the situation for judges that have already been removed from their positions. In Poland, both milestones relate to judges’ disciplinary procedures: one requires the state to establish an independent disciplinary organ, other than the Disciplinary Chamber, to review judges’ liability claims in the future.134 The other is much more onerous and requires Poland to establish an independent organ to review all proceedings against judges conducted by the Disciplinary Chamber so far.135

Accordingly, compared to Hungary where the super milestones seem significantly more technical and focus predominately on misuse of the EU funds, the Commission’s concern about judicial independence in Poland seems substantially more tangible. In this respect, the state is required to undertake more onerous measures, which not only require it to undertake a very specific course of action but, by demanding a restitutio in integrum, also alter its previous decisions. In addition to states’ differing attitudes, the Commission’s efforts seem to be enhanced also by the stakes involved. Namely, whilst the EU is expected to grant Hungary a total of 22 billion EUR of cohesion funds, along with a total of 5.8 billion EUR of post-pandemic recovery and regular budget funds, Poland is expected to obtain more than three times as much—namely, more than 35 billion EUR of post-pandemic recovery and 75 billion EUR of cohesion funds.136

In the ECtHR context, the task of specifying remedies by the Committee seems somewhat more complex. Generally, the ECtHR depends on voluntary compliance, granting states the opportunity to define the nature of required action. Accordingly, in the absence of the ECtHR’s instructions, the states interpret the rendered ruling and come up with remedial measures they deem would address the issue. They then communicate the idea, and later its execution, to the Committee. Normally, the Committee accepts such proposals if it agrees they represent appropriate redress and focuses merely on the follow-up of their enforcement.137 Sometimes, however, if the supervisory body deems that the ECtHR’s concerns have not been adequately addressed or if the state hesitates to comply, the Committee may spell out specific remedies according to its own interpretation of the ruling.138 The specification may be inspired by remedies other states have successfully adopted when faced with similar issues, but its detail varies.

The comparison of the Committee’s follow-up on cases related to judicial independence in Hungary and Poland seems to confirm this. For instance, following the Xero Flor case, the Committee issued two Decisions.139 One of the requirements of the first was that Poland ensures that ‘the Constitutional Court is composed of lawfully elected judges’.140 In the second Decision, adopted two months later, the Committee described the required remedies in significantly more detail, requesting Poland to ensure ‘that the Constitutional Court is composed of lawfully elected judges, and should therefore allow the three judges elected in October 2015 to be admitted to the bench and serve until the end of their nine-year mandate, while also excluding from the bench judges who were irregularly elected’.141 In contrast, following the cases against Hungary in Baka and Erményi, the Committee issued six Decisions. Each communication entailed merely a general requirement that Hungary submits ‘information on any measures adopted or planned’ to prevent similar future violations ‘devoid of effective and adequate safeguards against abuse’.142

Based on this, it seems as though Hungary is granted significantly more leeway to decide on the course of its own compliance in the ECtHR context, whilst Poland is asked to adopt a detailed list of remedies. Some might in this respect argue that such deference towards Hungary makes sense because the state also behaves better, at least compared to Poland. Indeed, Poland has consistently been terminating judges’ mandates throughout the years, which has also been found in several ECtHR rulings, whereas in Hungary this (officially) occurred only in Baka and Erményi. Yet, if we were to believe this, why then does the Committee keep Baka’s supervision open? Whereas in this respect Hungary’s better behaviour is disputable, the state’s better position to make any—future or past—action seem legal is not. The parliamentary supermajority allows the government to momentarily adopt any legislative basis required, making any action based on such legislation harder to criticize. This may indeed deter the Committee from interfering more strongly, but the looming potential of future amendments also facilitates its continued supervision and justifies its demands for assurances to prevent them.143

(ii) Dialogue sentiment

The last extrajudicial function of the two supervisory organs relates to the ability to condemn inadequate state compliance through negative language. The importance of language the supervisory organ uses in the monitoring process has already been acknowledged by the European courts. The ECtHR, for instance, in the infringement proceedings following the Ilgar Mammadov case specifically pointed out that it was the ‘language used by the Committee’ that ‘reflected its growing concerns’ about the lack of Azerbaijan’s cooperation.144 Important in this respect is that the ECtHR highlighted not only the expressive power of the language’s sentiment but also its ability to depict an increasing gravity of the situation, expressed through gradual condemnation of the state’s behaviour.

In this respect, the Commission uses several means of communication with states. To monitor the state of the rule of law specifically, the organ resorts to the annual Rule of Law Reports, which include chapters aimed at particular states. The first one being released in 2020, the Commission has so far drafted three cycles of such reports focusing on four areas, namely, the justice system, the anti-corruption framework, media pluralism and other institutional issues related to checks and balances. The sentiment analysis of all six reports, three for Hungary and three for Poland, however, reveals no surprising findings. Focusing on ‘both positive and negative’ developments across states,145 the Commission seems to have refrained from the use of distinctively positive or negative terms, which makes the sentiment of these reports generally neutral.146

The Committee on the other hand publishes its communications with states in the form of Notes, Decisions and Interim and Final Resolutions.147 This, however, occurs only very exceptionally following the most highly salient cases, typically where the views of the involved parties most notably diverge.148 Overall, the Committee in the post-2010 period issued Decisions following 11 cases against Hungary and in the post-2015 period following 12 cases against Poland. This amounts to a total of 38 Decisions against Hungary and 50 against Poland.

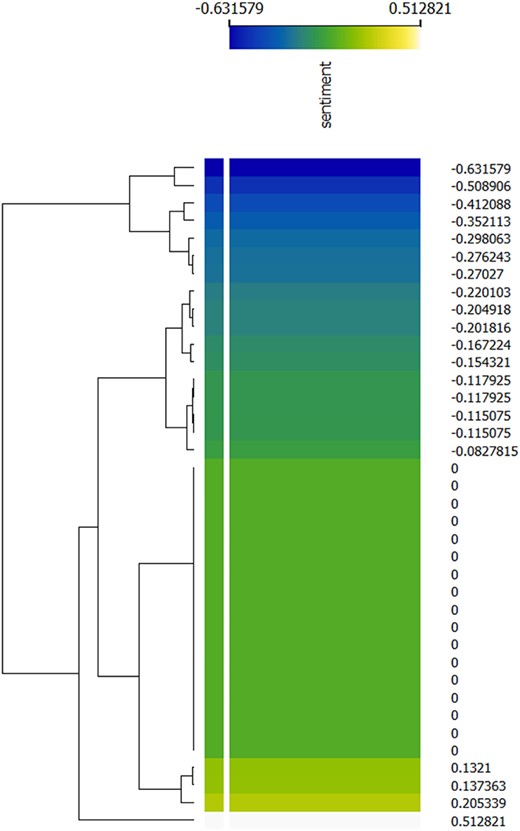

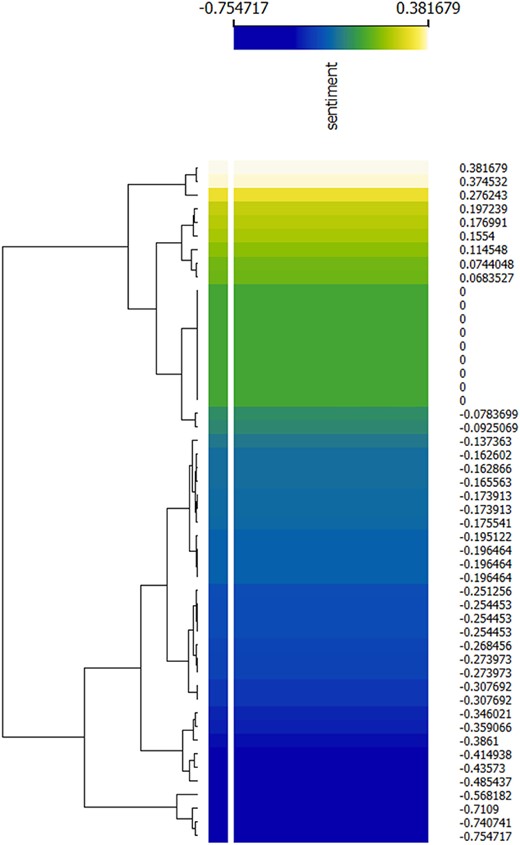

The analysis of their sentiment(s) reveals a significantly more condemnatory approach of the Committee toward Poland. In particular, the results first show that the Committee would issue a decision containing a generally negative sentiment more often against Poland than against Hungary.149 As shown in Figures 8 and 9 below, generally negative sentiment permeates 45 per cent of Decisions against Hungary (Figure 8) and 64 per cent of Decisions against Poland (Figure 9). Notable in this respect is also the scale of the two states’ sentiment scores (see the legends above the two graphs), revealing that the highest generally positive sentiment permeates Decisions against Hungary, whilst the Decisions against Poland contain the highest generally negative sentiment. Stated otherwise—when the Committee issues a generally positive Decision, it reflects a more positive sentiment if issued against Hungary, whereas a generally negative one contains an even more negative sentiment if issued against Poland.

Analysis of the frequency of specific expressions used by the Committee further reveals that the Committee used distinctly positive expressions such as noted with interest, welcomed and having satisfied itself (emphasis added) to incentivize Poland into compliance altogether 41 times across all its Decisions, whilst it used distinctly negative terms such as deeply regretted, expressed profound concern and noting the lack of progress (emphasis added) almost twice as often, namely 70 times.150 Against Hungary, expressly positive expressions such as noting important developments, noted authorities’ swift action and welcomed the authorities’ efforts (emphasis added) were used 48 times, whilst the Committee used negative expressions like deeply regretted and expressing deep concern (emphasis added) approximately as often, namely, 46 times. Indeed, this may indicate that the Committee uses substantially more condemnatory language against Poland, but it also shows that its attitude towards Hungary can hardly be considered favourable. The analysis offers another interesting finding in this respect. Compared to Hungary, the Committee generally refrains from inviting (emphasis added) Poland to take the required course of action and rather resorts to other, oftentimes more demanding phrases. In this respect, the supervisory body invited Hungary 85 times to act in a desired way, whilst this occurred four times less often in Poland, where the organ’s Decisions contained the term altogether 22 times. If the lack of favouritism is clear from the Committee’s dialogue with both states, this frequent resort to invitations nevertheless indicates a note of deference towards Hungary.

Furthermore, a rather more detailed sentiment analysis that adds to positive and negative and also neutral terms reveals that in Poland,151 the top three Decisions in which the ratio between the positive, neutral and negative language (i.e. compound factor) tilts to the negative, pertain to the cases of Reczkowicz and Xero Flor.152 In other words, the negative tone of the Committee is most extreme in cases condemning judicial independence. In contrast, the Hungarian counterpart Baka case, only ranks fifth in this respect, falling behind cases related to police ill-treatment and failure to investigate domestic violence.153 This adds an additional angle to the above findings: the Committee’s language against Poland is not only generally more condemnatory; the issue of judicial independence also ranks highest in the supervisory body’s concerns and surpasses all other issues. In contrast, this does not seem to be the case in Hungary.154

Last, the more condemnatory attitude of the Committee towards Poland is further reflected in the use of the specific ‘infringement phrase’, which arguably represents the preliminary stage of ECtHR’s infringement mechanism. In addition to the five cases related to judicial independence, the phrase appears throughout Decisions related to the lack of access to abortion and unlawful transfer of applicants facing the death penalty.155 In total, it was used 17 times. In all these cases, the Committee, before resorting to the ‘infringement phrase’, aggravated its language calling the state to comply.156 This was, however, not the case in Decisions addressing judicial independence, where the supervisory body ‘insisted upon the unconditional obligation’ of Poland to abide by the judgments of the ECtHR, in all, including its initial communications.157 On the other hand, the Committee used the phrase only in two cases against Hungary. The phrase first appeared in the 2019 Interim Resolution, which addressed excessive length of judicial proceedings and was used altogether four times after that.158 Without an exception, the phrase in this context reflects a notably softer language and is framed in general terms. This includes cases addressing judicial independence: after issuing several consecutive Decisions following the Baka case throughout 2017–21, the Committee used the infringement phrase for the only time in the 2022 Interim Resolution. The phrase emphasized ‘the legal obligation of every State, under the terms of Article 46, paragraph 1, of the Convention to abide by the final judgments of the European Court’.159 It is particularly interesting that the Committee later refrained from the use of the phrase in its subsequent and latest Decision in 2023.160

If the previous sections of the paper reveal Hungary and Poland’s different compliance strategies to identify different signals conveyed by the two states, this section relied on a sequential game of events to unravel how European institutions respond to these signals. Depending on the state involved, signals seem to either trigger or limit institutions’ judicial and extrajudicial functions. In particular, Hungary’s conciliatory signals merged with avoidance limit the punitive as well as the monetary part of the remedial function of European courts. Furthermore, the supervisory bodies’ functions to specify the required course of action for compliance only briefly touch upon the tangible rule-of-law-related issues, whilst the language used in dialogue with the state seems to be general and deferential. In contrast, Poland’s clearly signalled defiance triggers the two courts’ remedial and punitive functions, followed by tangible interventions of their supervisory organs. In this respect, the Committee and the Commission both formulate specific and detailed requirements, whilst Poland’s refusal to meet them triggers strong condemnation.

Based on this, one might argue that the signals Hungary and Poland convey act as a perpetual feedback loop for European institutions’ responses, which seem to adjust to these signals’ differing natures. This also finds support in theory: in environments of informational asymmetry such as black boxes of state compliance, international institutions largely depend on state signals. This is not only so that institutions may pinpoint non-compliance but also so that they can justify their interventions. In this respect, it seems that the more obvious state defiance corresponds to an opportunity for more frequent and more tangible interventions from institutions. This is confirmed by the above analysis, revealing how Poland’s standoff with the European institutions triggers their judicial and extrajudicial functions. Indeed, also the opposite is true: the more covert the resistance—which at times even resembles compliance—the weaker the potential for interventions due to fear of overreach. The example of Hungary’s conciliation and avoidance supports this, showcasing, in particular, the limited potential of institutions’ functions when faced with covert pushback techniques. The conclusion we may draw from this is that because some state signals limit, whilst others trigger institutions’ responses, this places these states (as agents emitting those signals) in control of the process. Where international institutions depend only on such signals, this leaves them with the ability to respond only in accordance with the gravity of conflict these signals convey.

In hindsight, it is also important to consider the particular historical and (domestic) political contexts in which this different treatment is rooted. Unlike Poland, Hungary became illiberal already in 2010. At the time, there were limited (if any) rule of law debates in the EU, and there existed only scarce mechanisms to react to its potential deficits. This gave the Hungarian government a head start on finishing the illiberal constitutional reform before the European institutions even had time to react. When Poland joined in after 2015, more mechanisms were in place, with some already triggered.161 Furthermore, the constitutional majority held by the Hungarian government (this has so far never been the case in Poland) allowed it to pass any domestic reform without having to resort to formal procedural violations. Even today, this limits the European institutions’ opportunities to (re)act, including by presenting a barrier to bringing individual cases before the ECtHR. Finally, whilst several domestic actors still persevere in opposition to the Polish government, Hungary’s domestic atmosphere seems more permeated with defeatism.162 This lack of domestic compliance partners may, in turn, facilitate a cost–benefit assessment by the European institutions. Limited by the lack of domestic mobilizing potential in Hungary, they might rather focus on Poland where their efforts may still make a difference. Coupled with Hungary and Poland’s signalled compliance strategies, this ultimately created and still perpetuates the two states’ differential treatment. In this respect, Hungary seems to be placed in a better position that allows it to influence the (success of) rule of law enforcement, whilst facing less resistance from the European institutions.

6. CONCLUSION

Irrespective of actual intentions, the two differing strategies—namely, Hungary’s covert resistance as indicated by a conciliatory attitude and avoidance and Poland’s overt defiance—signal to European institutions different levels of commitment to abide by the rule-of-law-related rulings. As the paper sought to uncover, this may be problematic from two angles: first, because states’ compliance processes largely remain black boxes, international institutions have limited knowledge about whether and how the implementation is actually going and what measures (if any) the states are actually putting in place. Second, as the European courts and their supervisory organs need to not only legally but also factually justify their interventions, they have to be careful about whether to intervene and if so, which tools to employ to nudge states towards compliance. This, the paper argued, makes their functions largely dependent on state signals. Accordingly, Hungary’s approach seems to draw not only less frequent but also fewer judicial interventions and of lesser gravity, followed by a more deferential attitude in the process of supervision. Poland’s attitude, in contrast, triggers more frequent and more severe interventions, including by having provoked the CJEU’s daily fine and significantly more condemnatory language of both supervisory organs. These findings reveal that the European institutions accommodate for differing state signals and that they (are forced to) adjust their responses to the particular compliance strategy of the state conveying them. At the same time, because of the European institutions’ different responses, these signals may either limit or trigger their specific interventions, depending on the state (and strategy) involved. This shows not only that signals indeed matter but also that states can in large part control them. In this way, states—as illiberal as they might be—may in fact importantly influence the European rule of law enforcement actions.

7. APPENDIX

Data and analysis in Signalling in European Rule of Law Cases: Hungary and Poland as Case Studies

A. Quantitative data

The article relies first on quantitative data generated based on 1105 reported cases against Hungary and 1723 against Poland from 1997 until November 2021. This information was retrieved from HUDOC ECtHR and HUDOC EXEC databases, both run by the European Court of Human Rights.163 To enable a comprehensive analysis of rule of law cases, I have also manually included relevant cases rendered and placed under supervision after November 2021.164 More specifically, the first batch of information related to judgment information (see section The coding tree, point A. below) and types of settlement (B.) were generated using the HUDOC ECHR database. The second batch of information relating to remedies (C.) and compliance data for each case (D.) were generated from the HUDOC EXEC database, which lists all cases that have been settled and followed up for compliance.