-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Azadeh Chalabi, A New Theoretical Model of the Right to Environment and its Practical Advantages, Human Rights Law Review, Volume 23, Issue 4, December 2023, ngad023, https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngad023

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Despite significant developments at the national, regional and international levels, to recognise the right to environment as a human right, this right is still under-theorised and contested. The challenge of giving a clear substance to such a standalone right is one that must urgently be taken up. Drawing on the NIC theory, this article develops a new model of the right to environment to serve three purposes: first, to shed light on the nature, scope and content of this right; second, to illustrate that this right can be considered as existing on three levels: individual, collective and global; and third, to explore the logical relationships between this right and already recognised human rights. This new model brings about various advantages at different levels. In particular, it allows for guiding practice for a range of actors from NGOs, human rights commissions and judges to governments and the UN human rights bodies.

1. INTRODUCTION

In a historic move, on 28 July 2022, the UN General Assembly released a resolution recognising a clean, healthy and sustainable environment as a human right with the majority of states voting in favour of it.1 One year before that, the UN Human Rights Council released a similar resolution recognising the right to environment.2 Despite these remarkable efforts which indicate a turning point in environmental human rights law, this right is under-theorised and contested. It is still unclear if the right to environment is a precondition to the enjoyment of other already existing human rights? What is the scope and nature of this right? What is the content of this right? Is this a collective or individual right?3 As Bridget Lewis argues, ‘one of the most compelling yet controversial areas of environmental human rights is the notion of a substantive right to an environment of a particular quality.’4 Even the proponents of recognising such right have admitted the challenge of defining what exactly this right means and that this challenge, if left unaddressed, can render the right ineffective and infeasible.5 MacDonald, for example, says that there are ‘dilemmas concerning the nature and extent of the right, the shape of the right, the content of the right, the threshold required to trigger harm under the right and other definitional and content-based hurdles.’6 This unsettlement can be explained by the fact that the right to environment was not initially articulated through a firm theoretical underpinning but rather has been suggested as a practical, yet theoretically baseless, response strategy in reaction to the need of society to be protected against environmental harms. The challenge of giving a clear substance to such a standalone right is one that must now urgently be taken up. It is particularly significant if we seek to include this standalone right in an internationally legally binding instrument.

As such, in this article, I will develop a new theoretical model of the right to environment in order to serve three main purposes: first, to illuminate the nature, scope and content of the right to environment; second, to illustrate that this right can be considered as existing on three levels: individual, collective and global; and third, to explore the logical relationships between the right to environment and already recognised human rights both in terms of classification and causality.

This new model is built upon the NIC theory of rights, advanced by this author elsewhere.7 NIC stands for Need, Interest and Capability. The NIC theory was advanced to go beyond the interest theory of rights, the needs-based approach to rights and the capability approach to rights putting forward an integrated account of human rights. These three major theories of rights have focused on one main concept, either interest, capability or need, and used that one concept in a rather isolated way, if not vaguely and imprecisely. Such deficit has led to conceptual reductionism in these theories. The NIC theory seeks to reconcile these three theories indicating that basic needs, interests and capabilities are interdependent, and all together form the foundations of basic human rights. The central proposition of the NIC theory is that ‘being endowed with a basic right consists of being capable of meeting one or more of basic needs in accordance with interests’.8 By explicating the conceptual definitions of human needs, interests and capabilities and illuminating the relationships among these three concepts and basic human rights, the NIC theory lays the foundation for developing this new model of the right to environment.

The suggested model can be significant at different levels from the ontological and epistemological through the methodological, semantic and practical level. At the practical level, in particular, it can inform not only legislators and policy makers in enacting or reforming existing laws and policies on environmental matters but also judges and other legal professionals engaged in environmental litigations. It can also foster legal uniformity among different jurisdictions on the matter of human rights and the environment, provide criteria for determining when the right to environment has been breached, and more importantly, set the stage for including the right to environment in an internationally legally binding instrument.

This article proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides a short profile of where we stand today examining the strengths and weaknesses of the two dominant approaches to the nexus between human rights and the environment: first, the greening of human rights approach and, second, the recognition of a new standalone right to environment. Based on the NIC theory, Section 3 advances a new theoretical model of the right to environment. This section consists of three sub-sections. It first illuminates the nature and scope of the right to environment and its link to basic human needs, human interests, basic capabilities and the natural environment. Then, it deals with the question as to whether a right to environment is a collective or individual right expanding the right to environment to include a three-level system of protection. This includes (1) right to environment as an individual right; (2) right to environment as a collective right; and (3) right to environment as a global right. The last part of this section offers a new categorisation of basic human rights in order to examine the logical relationships between the right to environment and already recognised human rights both in terms of classification and causality. Section 4 depicts the advantages of the new theoretical model at five different levels. Section 5 concludes.

2. WHERE DO WE STAND NOW?

Significant attempts have been made to interrelate human rights and the environment. After the Stockholm Declaration,9 however, a resistance against using rights language can be seen at the international level. In 1992, the Rio Declaration states that human beings ‘are entitled to a healthy and productive life in harmony with nature’ though it avoided using human rights language. Likewise, multilateral environmental agreements, as Knox states, almost never refer to human rights and environment, except the Paris Agreement which only uses human rights language in its preamble.10 Some of this resistance is political and rooted in the fact that some powerful states are still not willing to facilitate the link between human rights and the environment. For example, the United States blocked the proposal to recognise the right to environment in the early 1990s to convince the Human Rights Commission to consider a declaration on human rights and the environment.11 This approach can be seen, for example, in the negotiations surrounding the Paris agreement or more recently at the Glasgow climate change summit. The abstention vote of China and Russia to the recent UN General Assembly Resolution on the right to environment can also be understood in this light.

Despite all this political resistance, the nexus has been recognised in at least two different paths: (a) the greening of human rights; and (b) the recognising of a standalone right to environment.12 In what follows, I will explore the weaknesses and strengths of these paths. This section is aimed at laying the ground for explicating the concept of the right to environment in Section 3.

A. The Greening of Human Rights Path: Strengths and Weaknesses

Instead of recognising a standalone right to a healthy environment, the greening of human rights path highlights the environmental dimensions of already existing rights and protects the environment as a precondition to the enjoyment of human rights such as the right to life, health or adequate standard of living. In theory, this approach has often been appeared as a competing path to recognising a standalone right to environment. In practice, however, the African Charter is the only legally binding international treaty on human rights which makes the right to environment reviewable by an international adjudicative or quasi-judicial body,13 and this fact leaves human rights lawyers and other practitioners with no other option than greening human rights in order to protect a healthy environment in practice. Both the European14 and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights have found that environmental harm may result in the violation of existing rights protected under the European and American Conventions on Human Rights, including the right to life,15 the right to respect for one’s private and family life,16 the right to property,17 the right to adequate food and the right to water.18 That is why this path seems to be still the predominant one in practice.

Greening of human rights has been advanced to facilitate access to justice for victims of environmental harms and has given rise to a number of successful cases under regional and international human rights law.19 Despite the fact that this path has been beneficial in various ways, it has been proven insufficient to protect a healthy and sustainable environment comprehensively and adequately.

More specifically, this path can be criticised on at least six grounds. First, under this approach, negative impacts on the environment are only relevant if they interfere with the sphere of already existing individual rights.20 Second, being based on individual human rights, this path underestimates the collective aspects of environmental harms and the right of communities affected by environmental impacts. Third, the individualistic character of this path reinforces the difficulty of passing the traditional ‘but for’ test of deterministic necessary causation in environmental liability cases.21 Fourth, despite some recent progress,22 this path is still often backward-looking and hardly addresses the interest of next generations who will suffer the most from the effects of man-made environmental harms such as climate change.23 Fifth, the greening of human rights path is still more internal looking and territorial in practice. As Knox argues, ‘almost all of the environmental claims brought to human rights tribunals involve internal harm not regulated by international environmental law.’24 This is a significant shortcoming in addressing the transboundary nature of many types of environmental harms. Sixth, this path has failed to provide a firm theoretical explanation to link environment and already recognised human rights, and therefore, what has been proposed is more eclectic than integrated.

In short, due to the fact that environmental protection is offered only indirectly and conditionally, this path is faced with significant limitations in its effort to protect a healthy environment and in providing environmental justice to the victims.

B. Recognising a Standalone Right to Environment Path: Strengths and Weaknesses

Significant developments at the national, regional and international levels, in various forms, have been made to recognise the right to environment as a human right. The most recent one, at the international level, is the UN General Assembly Resolution on the recognition of a new human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment adopted in July 2022 which was supported overwhelmingly by member states. This comes one year after the UN Human Rights Council released a similar resolution. Although none of these resolutions are legally binding, they indicate a turning point as the UN has formally recognised this standalone right. At the regional level, the first regional human rights treaty to include an environmental right was the African Charter in 1981 recognising the right of all people to ‘a general satisfactory environment favourable to their development’,25 followed by the case law of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the African Court of Human and Peoples’ Rights.26 Seven years later, the San Salvador Protocol recognised the right ‘to live in a healthy environment’ as an individual right.27 Recently, in September 2022, the Council of Europe adopted a Recommendation on Human Rights and the Protection of the Environment calling on its member states to actively consider recognising the right to environment at the national level, even though neither the European Convention on Human Rights nor the European Social Charter includes the right to environment.28 At the national level, the recognition of a right to environment, in different forms, has increased dramatically. At the moment, the right to environment enjoys constitutional protection in at least 110 countries.29 In total, more than 80 per cent of the UN States Members (156 out of 193) legally recognise the right to environment.30

Recognising a right to environment can serve at least five purposes. First, it can elevate such an extremely important matter to the same level as other human rights, well beyond just a preference or matter of policy. Second, it can improve accountability and environmental justice by paving the way for bringing an action against states and non-states actors for failing to protect the environment or for their environmentally damaging activities.31 Such recognition can act as ‘a lever to overcome classical hurdles in human rights-based environmental litigation, such as locus standi and, more generally, a burden of proof that is often too heavy on applicants’.32 In such cases, claimants only need to ‘establish that the activity in question resulted in creating an unhealthy environment’.33 Third, the recognition of such right can confer more power on some agents particularly NGOs from the local level to global level. Fourth, this recognition can create a collective sense of the critical importance of environmental protection34 and helps ‘energize movements and coalitions advocating for the right’.35 All this can enhance environmental protection in itself and push us towards eco-centrism. Apart from moral aspects of ecocentrism, as mentioned in the statement of the World Charter for Nature of the United Nations General Assembly, humanity benefits from healthy ecological biodiversity.36 The fact of the matter is that anthropocentrism alone is indeed inadequate for conserving a sustainable environment with biodiversity which is vital for life (including human survival) on planet. Fifth, such recognition can increase environmental awareness of individuals about the ecological crisis including the impacts of human behaviour on the environment and the significance of protecting it over time.

However, this new standalone right has been criticised as being far from clear and as a distraction from improving the link between environment and human rights. Gunther Handl, for instance, argues that these are ‘duplicative efforts without ever coming close to bringing about the same environmental benefits’.37 They believe that the recognition of a new right would be redundant and cannot achieve anything more than what is already possible under the existing laws and policies. As Lee argues:

[F]or the right to be practically useful, it needs to be defined narrowly enough to allow a claim to be brought before a court … For a right to a healthy environment to be actually useful, … it must be capable of being defined in such a way as to be applicable to specific real-life situations. Without this rigorous definition, a right to a healthy environment risks remaining an irrelevant member of the group of third-generation human rights which have proliferated recently.38

In response to such criticism, in 2020 the UN Human Rights Council released a report on the right to environment in which the UN Special Rapporteur, David Boyd, seeks to describe good practices followed by states in recognising the right to environment in order to address both the procedural and substantive elements of the right. The report recognises four procedural elements including access to information, public participation, access to justice and effective remedies. The substantive elements, recognised in this report, include clean air, a safe climate, access to safe water and adequate sanitation, healthy and sustainably produced food, non-toxic environments in which to live, work, study and play, and healthy biodiversity and ecosystems.39

Despite the fact that the report has made a good effort to shed light on the right to environment and indeed can be seen as a great starting point, it suffers significant shortcomings as follows. First, drawing upon practices of different countries, this report is based on an a la carte approach and, therefore, it is easy for things to fall through the cracks. For example, access to water has been identified as one of the ‘substantive elements’ of the right to environment but it is not clear why other elements of the environment such as soil and plants are absent. Noise pollution has also not been mentioned. Likewise, two substantive elements listed in the report (i.e. clean air and access to safe water) can be covered by another broader element, namely non-toxic environment. Second, although drawing upon good practices is indeed insightful and should not be under-estimated, such reports are often not grounded in a theory. Being a theoretically baseless report reminds us of the line which has been attributed to Kant: ‘theory without practice is empty and practice without theory is blind’.40 There are many unanswered questions in the report. For example, it is not clear where this right comes from theoretically. The report has also not clarified whether the right to environment is a collective or individual right. Indeed, there are inconsistencies. For example, the word ‘sustainably’ has been used only for ‘food’ in this report but not for other elements such as soil and water. Third, the added value of a new standalone right to environment to the human rights corpus remains unclear in this report. For example, the report specifies clean air and access to safe water—which have been already recognised as individual rights—as the two elements of the right to environment. Yet, it has not clarified the logical relationship between the already existing ‘right to clean water’ and ‘clean water as part of the right to environment’. Moreover, the report seems to be based on an isolated individualistic approach leaving the link among the substantive elements of the right to environment undiscussed.41

Having examined both the greening of human rights and the recognising of right to environment as the two paths currently used to link human rights and the environment, the fact of the matter is that neither of them are initially articulated through a firm theoretical foundation. But rather they were put forward as an innovative, though reactive, response strategy against environmental degradation and the need of society to deal with it. Although the right to environment path has more potential to enhance environmental protection, the recognition of a new right to environment without an adequate theoretical justification can weaken the integrity and strengths of existing human rights.42 The lack of theoretical foundation which resulted in conceptual vagueness and ambiguity can have significant repercussions. First, this vagueness can make it easier for the state and non-state actors to avoid bearing any clear obligations to protect the environment appealing to the fallacy of equivocation. For example, the reason raised by some states who abstained from the UN Human Rights Council resolution on the right to environment, such as China and Russia, was that the content of the right to environment is unclear.43 There is indeed an urgent need to settle on a clear definition before corresponding obligations can be identified. Second, the ambiguity in what exactly the right to environment means implies risks in planning future activities to address environmental degradation. Third, this can also explain the difficulty of establishing sufficiently objective and broad criteria against which to conduct human rights impact assessment and policy analysis on environmental matters. Fourth, inconsistency in the form and substance of what is labelled as ‘right to environment’ in various domestic legal systems is another consequence of this vagueness. Fifth, this makes it difficult to set appropriate criteria for determining when the right has been breached and therefore has a negative impact on its justiciability and enforcement in practice. Sixth, the lack of firm theoretical model can obscure the significance of the right to environment in the human rights corpus and the added value of recognising such right to other existing human rights.

Adopting the NIC theory of rights, developed by this author,44 in the next section this article will explicate the right to environment articulating a theoretical foundation for the nexus between human rights and the environment.

3. A NEW THEORETICAL MODEL OF RIGHT TO ENVIRONMENT BASED ON THE NIC THEORY

As mentioned before, the NIC theory as an integrated approach is advanced through the positive critique of the interest theory of rights, the needs-based approach to rights and the capability approach to rights. Despite significant strengths, these three approaches have some important weaknesses. Going into the full details of these weaknesses, which have been discussed by the author elsewhere,45 stands beyond the scope of this article. Instead, I will only briefly mention some deficiencies here.

An important issue with the needs-based approach to human rights is that it often only focuses on the objective concept of basic needs with disregard for individual and cultural differences. Dictatorship over needs in Soviet Communism where the ‘need-principle’, with a particular emphasis on ‘material needs’ (goods and services), provided a theoretical legitimation for paternalistic politics, has possibly discouraged some jurisprudential writers from any mention of the concept of need in their works.46 This approach has also neglected the fact that people have different capacities to convert resources into what they need or want and may need extra resources.47

As its name implies, the interest approach is focused on human interests but surprisingly it suffers from a remarkable absence of any coherent discussion about the definition of the concept of ‘interest’. A right in different versions of this approach is either grounded in (certain) ‘interests’ or is to further right-holders’ ‘interests’, though the same linguistic label ‘interest’ has been used with different connotation across different versions of this theory.48 Their failure to adopt a systemic approach, has led to a blurred use and polysemous analysis of ‘interest’ which can distort our understanding of rights. Moreover, there is a network or apparatus of interconnected but district concepts—namely basic needs, capabilities, values, wants, preference, happiness and well-being—which is either overlooked by interest theorists or they use them loosely or interchangeably.49 Another challenge raised is the ‘expensive teste objection’ which is more an issue in the case of economic interests.50 The main problem with the interest theory is that human interests cannot be seen as the only base of rights, mainly because of the fact that in ontological sense, the existence of interest is dependent on basic needs.51

A major challenge for the capability approach is that it is difficult to think of capability as the mere basis of human rights because there are an uncountable number of capabilities people may have, and not all of them can be regarded as a positive one. Instead, some of them have even a negative value. People can make mistakes in the process of making choices about the various states of being or doing they can take and this can perhaps justify the need for an objectively universal base (like basic human needs) of rights.52 While some see capabilities as universal, others take a more relativist view.53 Some have also criticised this approach as it appears to impose an external valuation of the good life.

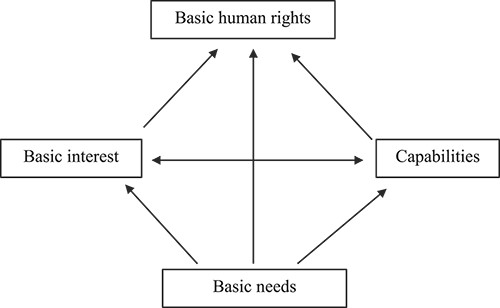

Whereas these three approaches have focused on one concept and are often seen in opposition, the NIC theory seeks to reconcile them putting forward an integrated account of human rights. It shows that basic needs of all types are interdependent, but also basic needs, interests and capabilities, upon which basic human rights are grounded, are interrelated. Ontologically speaking, human beings have objective basic needs without which they cannot survive (primary basic needs) or be healthy (secondary basic needs).54 What can meet basic human needs are ‘valuable items’55, and interest is what connects ‘valuable items’ (object, processes, properties of objects and properties of processes) to basic needs. Basic needs and interests are also related to human capabilities which are what a person is able to do or liable to be.56 Meeting needs paves the way for the enhancement of capabilities through interests. Also, one’s capabilities (physical, emotional, intellectual, etc.) are relevant to her choice of interests, and one’s interests can direct her to enhance relevant capabilities.57 According to the NIC theory, ‘being endowed with a basic right consists of being capable of meeting one or more of basic needs in accordance with interests.’ (Figure 1).

Sources of Basic Human Rights. Source: Chalabi, National Human Rights Action Planning (2018) at 55.

In what follows, I introduce the new model, which I would call the NIC-based model of right to environment, fleshing out the nature, scope and content of the right to environment.

A. The Nature and Scope of Right to Environment

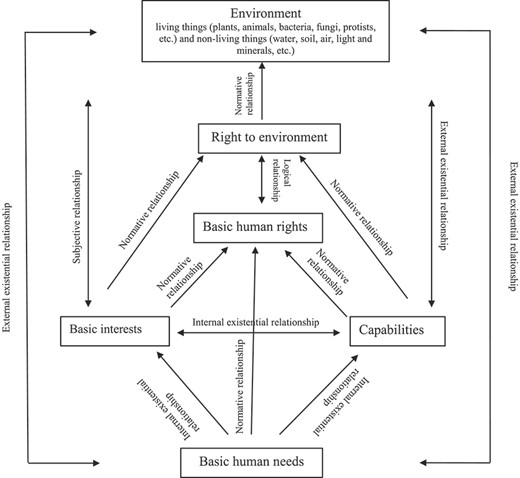

As Figure 2 indicates, there is an external existential relationship (ontological) between the environment and human beings including human needs and capabilities (and indirectly human interests). This is due to a number of factors. First, the human being is not and cannot be separated from the environment, that is, the idea of human-being-in-environment. Second, the environment is the only source responsive to some primary basic human needs,58 such as the need for air, water, food and shelter. Third, this unique meta-source, which includes various resources (air, water, land, etc.), is non-replaceable (at least based on our current knowledge). These three objective facts imply that certain qualities of the environment which can make human beings capable of meeting their needs are valuable to human beings and should be recognised as a standalone human right.

According to this model, being endowed with a right to environment consists of being capable of living in an environment of certain qualities where human beings can meet their basic needs in accordance with their interests. The phrase ‘certain qualities’ here refers to not only those qualities which can make human beings capable of meeting their basic needs in accordance with their interest such as being clean and healthy but also the sustainability of an environment with such qualities over time.

As Figure 2 shows, there is a reciprocal relationship between the environment and human capabilities. Enhancing capabilities can enable human beings to protect (or damage) the environment and vice versa. Likewise, there is a ‘subjective relationship’ between human interests and the environment. On the one hand, the natural environment, like the social environment, can play a role in shaping one’s interests (e.g. a person living in close proximity to forest land may develop different interests from someone living near the sea) and on the other hand, individuals may have different interests towards environment. However, as environment is the only source responsive to some basic human needs and the concept of basic interest is closely related to the concept of basic needs, the degree of choice and, therefore, subjectivity of interests here is low. For example, people with dementia may rarely feel thirsty or hungry but there is no doubt that food and water are in their objective interest. As our interests here are more objective than subjective, our need for and interest in an environment of certain qualities largely overlap or become almost the same. That is, the external existential relationship between the environment and human needs and capabilities can be found indirectly between environment and human interests as well, though even in the case of primary basic needs such as water, some degree of subjectivity in terms of its properties is present. For instance, one is interested in cold water, the other person in room temperature and the third one may be interested in hot water early in the morning.

It should be noted that the right to environment is not just an ‘umbrella’ right, or the sum of the already existing rights but rather a composite right. This is because of the fact that the ecosystem is so intertwined that often any damage in one part can cause damage in other parts of the environment. Adopting a systems approach, the environment as a system can include both non-living and living beings, humans and non-humans, which are interdependent, and their survival depends on biodiversity at different levels from genes to biomes. The key point is that often harm to any aspect of the environment can be seen as harm to the environment as a whole. For example, as the global temperature continues to rise, the glaciers start melting and this will increase the sea levels. Following that, farms will be flooded, and coastal cities may be immersed. Apart from its influence on the level of food security, all this may make people migrate to other places and can have negative impacts on economies and their role in sustaining everyone. This could gradually make a habitable place unlivable in the long term, if not in the short term. Biodiversity and sustainable environment are objective needs of both humankind and other species, and thus protecting the environment is where the interest of both overlaps.

The intertwining of the elements of the environment implies that any act or omission which contributes negatively to the qualities of the environment and its sustainability over time will be in violation of the right to environment. What is important here is to protect the environment as a system of non-living things (water, soil, air, light and minerals, etc.) and living things (humans, animals, plants, bacteria, fungi, protists, etc.) and its biodiversity (especially ecological diversity) over time.

Having discussed the nature of the right to environment, one may wonder if this is a collective or individual right? According to the new theoretical model suggested here, the right to environment is a multi-level concept.

B. Right to Environment as a Multi-Level Concept

There have been varied approaches to explaining what conditions are required for a right to be considered a collective right. Some scholars draw the distinction between collective and individual rights based on the capacity to exercise a right, that is, individual rights can be exercised only individually and collective rights can be exercised collectively.59 Although this defining condition may work in many cases, there are counter-examples.60 For example, there are some individual rights such as the rights to assemble, to strike, to associate freely or to speak one’s language in public which can be exercised only collectively, by a group of individuals.61 These counter-examples are also enough to show the shortcomings of those theories which focus on the subject of right arguing that collective rights can be held only over particular type of goods such as ‘participatory goods’62 (Denise Re’aume’s theory)63 or ‘socially irreducible goods’ (Taylor’s account of collective right)64.

Another common account of collective rights in the literature is focused on the ultimate interest a right can serve, that is, collective rights serve the interest of the group as such and not individuals.65 The interest-based account of collective rights has different versions developed by, among others, Joseph Raz, David Miller, Dwight Newman, Miodrag Jovanović, Larry May, Paul Sheehy, Keith Graham.66 Accounts, such as Raz’s and Miller’s, require individuals to be members of a group before they can go on to have shared interests that might ground a collective right. As such, membership of a group in virtue of something other than their shared interest is a precondition of having a collective right based on their shared interests.67 This condition is associated with the traditional corporate concept of collective (group) rights, that is, the right-holding group has an identity and existence that is separate from its members.68 It is not, however, clear why a number of separately identifiable individuals who share some common interests cannot hold collective rights even if they don’t form a group in advance. For example, pedestrians who do not necessarily have any common identity have a collective right to have footpaths. In this case, the interest of no single person is sufficient to justify holding authorities to the duty to build footpaths, rather it is in their shared interests.69

Having briefly discussed the main accounts of collective rights in the literature, three clarification points need to be made here:

First, the conception of ‘collective’ in this context is different from the ‘corporate’ conception of the group which has often been used as a single unitary entity which is not reducible to the standing of group members.70 What is meant by ‘collective’ can be regarded as a continuum with one pole ‘group’ in the strict sense (primary groups such as family and secondary or formal groups like hospital, school and university) and the other, aggregation or collection of individuals who do not have necessarily any common identity but happen to share the same interest such as pedestrians. Second, collective rights should not be confused with ‘group differentiated’ rights that people possess in virtue of being group members and that right can be either collective or individual.71 Third, as will be discussed in the case of the right to environment, individual rights and collective rights are not necessarily in conflict with each other but rather they can co-exist or even complement each other. The same good can sometimes be the subject of both individual and collective right.72

While each of the defining conditions discussed above is deemed to be insufficient, a combination of them seems to be more adequate for the purpose of defining a collective right. More specifically, in the case of the right to environment, some further conditions such as the scope and severity of harm can be taken into account as well. Adopting different criteria, including: the capacity to exercise the right, ultimate interest, the subject of right, and the scope and severity of harm, this section expands the right to environment as a multi-level concept offering a three-level system of protection: (1) right to environment as an individual right; (2) right to environment as a collective right; and (3) right to environment as a global right.

(i) Right to environment as an individual right

The right to environment as an individual right is ascribed to individuals who can wield the right, that is, exercise it, invoke it to make a claim or waive it independently in her own name or on her own authority. The right to environment at this level can be exercised only individually. The ultimate interest at this level is an individual interest and the environment is a socially reducible good that is enjoyable by an individual regardless of its impact on other recognised rights. The scope and severity of harm at this level can be limited to specific person(s) and the number of people affected can be low with often even focusing on the current or near future harms. For example, a plaintiff may file a lawsuit challenging the pollution of a nearby stream or the noise pollution caused by a rock crusher next to her house.73

(ii) Right to environment as a collective right

Beyond individual entitlement, which is universal and covers every human being, the right to environment is a collective entitlement which pertains to groups of different forms. At this level, preserving an environment of certain qualities as a collective good over time is in our collective interest. The right at this level involves many environmental harms, such as polluted water, species under threat of extinction, and contaminated air which may be difficult to identify as an injury to an individual plaintiff but are a threat to human health and survival over time. The right to environment as a collective right has to do with biodiversity (in particular, ecological diversity) and sustainability over time. If, for instance, pollution prevents the use of a public beach or kills the fish in a navigable stream and thus potentially affects all members of the community, it impinges on the right to environment and can be characterised as a collective right. Marine pollution in Teluk Bahang, Malaysia can be an example here. Oil spill cases such as the Ixtoc 1 Oil Spill in 1979, the Mingbulak (or Fergana Valley) Oil Spill in 1992 and the Kolva River Spill in 1994 can be taken as some other examples.

The right to environment at this level is a ‘dual-standing collective right’, in Buchanan’s term. Buchanan distinguishes between two types of collective rights: non-individual collective rights and dual-standing collective rights. Non-individual collective (or group) rights can be wielded—that is, exercised, invoked to make a claim or waived—non-individually by the group through some collective procedure or by some agent(s) on behalf of the group whereas in the case of dual-standing collective rights, ‘any individual who is a member of the group can wield the right, either on his own behalf or of any other member of the group, or the right may be wielded non-individually by some collective mechanism or by some agent or agents on behalf of the group’.74 The key point here is that whereas any member of the group can exercise the right or invoke the right to make a claim, no one can wave it individually or destroy the subject of a dual-standing right by herself.75 This makes it different from an individual right. As Trindade points out:

Such rights pertain at a time to each member as well as to all members collectively, the object of the protection being the same, a common good (bien commun) such as the human environment, so that the observance of such rights benefits at a time each member and all members of the human collectivity, and the violation of such rights affects or harms at a time each member and all members of the human collectivity at issue. This reflects the essence of ‘collective’ rights, such as the right to a healthy environment in so far as the object of protection is concerned.76

The right to environment as a dual standing collective right is also different from ‘non-individual collective right’ where the protected good is a participatory or shared good and cannot be enjoyed individually (only communally), such as the right to self-determination.

Likewise, this must not be confused with the fact that collective rights might well be established irrespective of possibilities of enforcing them.77 Also, this must not be confused with ‘joint rights’ when the protected good is the subject of both individual and collective right at once, though this can happen in the case of the right to environment. For example, if the river runs through a landowner’s land, we can talk about the right to environment as a joint right. Whereas the landowner will own the riverbed and has an individual right to the natural flow of water through their stretch of the river, she must not do anything which would obstruct, pollute or divert the river as it would violate the collective right of others. Such cases, however, look more like an exception than a rule.78

(iii) Right to environment as a global right

The natural environment must be protected in the context of global ecosystem which is based on biodiversity. The right to environment as a global right has to do with the level of protection when environmental damage can be a threat to life on the planet. Although this level can be logically placed under the previous category (right to environment as a collective right), the scale and severity of climate change to humanity combined with the fact that the damage might be irremediable demands a higher level of protection. The delayed nature of harm or so-called ‘latent harms’ is a distinctive feature of environmental harms at this level which is related to inter-generational dimensions of global environmental crisis, in particular climate change. At this level, the protection of the environment against climate change can be defined as a global right. Instead of collective interest, here we can talk about ‘global interest’ to protect the environment from the detrimental effects of global warming and climate change.

Explicating the right to environment as a three-level concept can help us to shift from a ‘one-size-fit-all’ approach to a more graded concept of environmental harm to take different factors, such as severity, scope and irreversibility into consideration. The current approach seems to be based on binary logic. Whereas environmental harms vary significantly, they are not grounded in a graded concept of harm. No matter whether a case is about a small damage at the individual level or relates to climate change which is a threat to life on the planet, all are addressed with the same or similar standards. A gasoline leaks from a service state and oil disaster in the Niger Delta both are dealt with the same standards. Having expanded the right to environment as a three-level concept, each level demands a different form of protection in terms of, among others, types of obligation (result or conduct), duty holders, legal standing and litigation/tribunals. For example, one of the most important consequences of recognising the right to environment as a global right is that it would be in a strong position to achieve the status of jus cogens or peremptory norm with erga omnes effect. This protective system can also expand legal standing for significant environmental harms such as climate change to include NGOs, National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs), etc. Exploring these differences for each level requires further research and stands well beyond the scope of this article.79

The next question to be addressed is what the logical relationships between the right to environment and already existing human rights are.

C. Right to Environment and Existing Human Rights

The logical relationships between the right to environment and already existing human rights can be discussed in two senses: classification and causality. In illustrating the logical relationships, it helps to draw a distinction among three categories of human rights. The first category, which I would call category A, includes those human rights whose subject is an element of the natural environment such as the right to clean water, clean air and food. These rights fall into socio-economic rights. The next category, which I would call category B, includes those human rights whose subject is not an element of natural environment, but their subject is directly influenced by the natural environment such as the right to health, life, work, housing and education. These rights fall more into socio-economic rights, though some civil and political rights such as the right to life or privacy, home and family life can be found here. The last category, called category C, includes those human rights whose subject is not directly related to natural environment such as freedom of religion and freedom from torture. These rights belong more to the category of civil and political rights.

Category A, namely those rights whose subject is an element of the environment, logically can be seen as a sub-set of the right to environment as an individual right. The best example includes the right to clean water which enables ‘everyone to sufficient, safe, acceptable and physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic uses’.80 The conceptual space of the right to environment is broader than the right to water not only because it covers other elements of the natural environment such as air and soil but also because it is not conditioned by ‘personal and domestic use’. If, for instance, a company provides sufficient clean water enough for personal and domestic use but at the same time pollutes the main rivers in the area, this will be in violation of the right to environment though it may not be the case for the right to water as currently defined by the ICESCR in General Comment No. 15. As for category B, the right to environment as an individual right can have overlap with rights such as the right to health but their conceptual spaces are not the same. Using Venn Diagram terms, there are two intersecting circles. In this case, for example, there are some similarities between the subject of the right to environment and some underlying determinants of the right to health such as water and air. There might be cases where someone’s right to health is violated because of, for example, harmful traditional practices or a lack of access to essential drugs which may have nothing to do with natural environment directly. As for category C, although in terms of subjects these rights and the right to environment appear to be unconnected circles such as the right to free elections and the right to environment, as will be discussed shortly, there can be a mutual causal relationship between them.

So far as the causal relationships are concerned, the right to environment as a composite right on a multi-level scale, can pave the way for more effective realisation of basic human rights of almost all the categories identified above. The main focus here is more on top-down causality (from macro to micro level). The right to environment as a multi-level right has to do with biodiversity and sustainability which can have an impact on the realisation of individual rights over time. That said, bottom-up causality matters here as well. There is a mutual causal relationship between the right to environment and most (if not all) basic individual rights which are already recognised. The right to health can be an example here. On the one hand, a clean, healthy and sustainable environment as one of the underlying determinants of the right to health, can reduce vulnerability to ill-health, as mentioned in Article 12 (2b) of ICESCR. On the other hand, the realisation of some basic rights such as the right to health can improve the realisation of the right to environment. Take the right to education as another example. On the one hand, air pollution has been linked to poor academic performance. For example, ‘students learning in close proximity to the coal-fired power plants in Chicago or the toxic chemical sites in Florida have worse attendance and worse test scores than the national average.’81 On the other hand, environmental education is crucial for awareness raising and informing people about their responsibilities toward the environment and this can help realise the right to environment in practice.

This reciprocal causal relationship is also true in the case of most civil and political rights. On the one hand, all basic individual rights need to be exercised in the environment and therefore the quality of the environment is always crucial. The environment influences our capabilities and this can have an impact on, for example, the right to freedom of expression, to vote or religion. On the other hand, as shown by Nobel prize winner, Amartya Sen, democracy can avoid famine mainly because the right to information and the right to free expression.82

In the next section, the basic advantages of this model at different levels, starting from the ontological to the practical level will be discussed.

4. THE ADVANTAGES OF THE THEORETICAL MODEL OF RIGHT TO ENVIRONMENT

The advantage of this new model can be depicted at the ontological, epistemological, methodological, semantic and practical levels.

At the ontological level, this model provides an ontologically objective base (ontological objectivity) for the universal recognition of the right to environment. This objectivity is built upon the fact that the referents of the three main pillars of this model enjoy the status of ontological objectivity. The environmental resources, as one of these main pillars, are either things (such as oxygen, water, river, mountains) or processes (such as atomic collision, chemical compositions, metabolism) with bundle of primary properties (such as temperature, velocity, wavelength, sound frequency, density).83 The referents of the other two pillars of the model, namely, primary basic needs and basic capabilities (such as to breathe, walk, eat and learn), are objective facts. As for basic interests, the fourth pillar of the model, it should be stressed that although basic interests are secondary properties of human being, they are highly correlated with basic needs, that is, the existence of interests is dependent on basic needs.84

At the epistemological level, this model provides an epistemically objective base (epistemic objectivity)85 for the universal recognition of the right to environment. This objectivity is built upon the fact that (a) the main referents of this theoretical model enjoy the status of ontological objectivity, and (b) in semantic terms, all the concepts utilised in the model have external reference rather than internal reference. Methodologically, this model can provide a platform upon which multi-disciplinary research, both quantitative and qualitative, on various aspects of the right to environment can be conducted. In particular, the suggested model can inform further research on objective criteria for the evaluation of laws and policies on human rights and environment from micro level to global level as well as research on sustainable development including sustainable development goals. Moreover, the new categorisation of existing human rights offered in this model can be used by academics working on environmental human rights law. At the semantic level, the theoretical model developed here is hoped to help lessen the possibility of appealing to the fallacies of ambiguity in particular the fallacy of equivocation, unintentionally or intentionally, when the interests of some powerful collective actors such as states and corporations arise.

More importantly, at the practical level, this new model can serve at least ten purposes. First, it can inform legislators and policymakers in enacting or reforming already existing laws and policies on the right to environment. It can be especially significant if we seek to include such right in a legally binding instrument at the international level. Second, this new model can be used by the UN human rights bodies in interpreting the right to environment, articulating corresponding legal obligations and monitoring its implementation in practice. It can also be used by judges and other legal professionals engaged in international litigation of environmental matters. Third, the suggested model could have some contribution to fostering legal uniformity among different jurisdictions on the matter of human rights and the environment. Perhaps the UN human rights bodies, including the UN human rights council and the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment, can use this model to encourage uniformity across jurisdictions. Fourth, shedding light on the links between the right to environment and human needs, interests and capabilities, this model can be used by human rights policy makers, planners, NGOs, governments, NHRIs and intergovernmental organisations for environmental and human rights impact assessments and policy analysis at different levels from the community level to the national, regional and international level. Fifth, the new model developed in this research can help provide criteria for determining when the right to environment has been breached. The forgoing analysis has demonstrated that recognising the right to environment as an individual right would have the benefit of allowing a violation to be found irrespective of whether there had been any link between environmental degradation and the impairment of a protected human value such as life, health or cultural considerations. This makes this standalone right separate from other existing basic individual human rights such as the right to life or health. Unlike other existing human rights which were not formulated with the specific purpose of protecting the environment and their environmental dimension was introduced much later, the right to environment is formulated to protect the environment and the protection afforded to environment here is not conditioned on the existence of a link between environmental degradation and an impairment of an already existing human right. Sixth, the categorisation of human rights offered here can also be used in environmental litigation by claimants or judges to identify the rights affected. In particular, this can be used by courts at different levels, tribunals and arbitral panels as a heuristic device to identify and interpret the rights affected in complex environmental cases. Seventh, this theoretical model can be employed as a heuristic device by practitioners in human rights action planning on environmental matters. Eighth, the multi-level system of protection suggested here can be used by legislators at the national level to categorise environmental harms and provide different levels of protection at the individual, collective and global levels. Nineth, this three-level protective system can also be employed to redefine states and non-state actors’ discretionary power on environmental matters with different degree of severity. For example, recognising the right to environment as a global right can confer more power on some agents particularly NGOs from the local level to global level and constrain states discretion. Tenth, this three-level system of protection can shape a stronger base for international cooperation, as a ‘fundamental principle’ of international environmental law, recognised in the Stockholm Declaration4 and the Rio Declaration, at least on collective and global aspects of environmental matters paving the way for non-states actors to get more effectively and genuinely engaged.

5. CONCLUSION

In July 2022, in a historic move, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution recognising a clean, healthy and sustainable environment as a human right with the majority of the states voting in favour of it. This timely effort indicates a turning point in environmental human rights law. Yet, this new standalone right has been widely criticised as being vague and that this vagueness can influence its effectiveness and feasibility in practice. Even attempts to recognise such right have been criticised as ‘duplicative efforts’ without any added value. Drawing upon the NIC theory as an integrated approach, this article put forward a new theoretical model for the right to environment built upon the five key concepts of basic needs, interests, capabilities, basic human rights and the environment, and five different types of relationships. The relationships include internal existential relationship, external existential relationship, normative relationship, subjective relationship and logical relationships.

Another key conclusion to emerge from this model is that the right to environment is a multi-level concept and can be defined as an individual, collective and global right. This is a shift from ‘one-size-fit-all’ approach to a more graded model of environmental harm to take different factors, such as severity, scope and irreversibility into consideration. Having expanded the right to environment as a three-level concept, the task ahead involves defining different forms of protection in terms of, among others, types of obligation (result or conduct), duty holders, exact beneficiaries of each level, legal standing and litigation/tribunals for each level. The foregoing analysis depicted the advantages of this new model at the ontological, epistemological, methodological, semantic and practical levels. In particular, this model allows for guiding practice for a wide range of actors from NGOs, national human rights commissions and judges to governments and the UN human rights bodies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The first draft of this article was presented at ESRAN-UKI workshop in Manchester. Many thanks to the ESRAN-UKI network members, in particular Felix Torres, Judith Bueno de Mesquita, Ben Warwick and Claire Lougarre, for their feedbacks. This article also benefited from the valuable feedback and comments provided by the Liverpool School of Law and Social Justice Pre-Publication Reading Committee, especially Professor Nicola Barker and Professor Michelle Farrell. I am also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments. Finally, I want to thank my father, Massoud Chalabi, emeritus professor of sociology, for all the productive discussions we had and his invaluable comments on this article.

Footnotes

This includes 161 votes in favour and eight abstentions. See GA Res, 28 July 2022, The human right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment, A/76/L.75.

UNHRC Res, 18 October 2021, A/HRC/RES/48/13, Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development. This resolution was released following at least three recent ‘joint statements’ endorsed by 69 states, 15 UN entities and more than 50 human rights experts, including the Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, which called upon the UN to adopt a resolution in 2021.

A wide variety of formulations are used including, among others, the right to a ‘clean’, ‘healthy’, ‘balanced’ and ‘harmonious’ environment. In some countries, the right to environment is recognised as an individual right and in others as a collective one. In most cases, it is formulated as an anthropocentric right, though in some cases, it is more in harmony with ecocentrism (e.g. Ecuador, Bolivia and New Zealand). See Daly and May, ‘Learning from the Constitutional Environmental Rights’, in Knox and Pejan (eds.) The Human Rights to a Healthy Environment, (2018).

Lewis, Environmental Human Rights and Climate Change: Current Status and Future Prospects (2018) at 59.

See, e.g. Handl, ‘Human Rights and the Protection of the Environment’ in Eide et al., (eds.) Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2001) at 303; Pevato, A Right to Environment in International Law: Current Status and Future Prospects (1999) 8 (3) Review of European Comparative & International Environmental Law, 309.

MacDonald, ‘A Right to a Healthful Environment-Humans and Habitats’ (2008) European Energy and Environmental Law Review 213, at 214.

Chalabi, National Human Rights Action Planning (2018) at 45–65.

Ibid.

Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment, in Report of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, UN Doc. A/CONF. 48/14, at 2 and Corr. 1 (1972).

Knox, ‘Constructing the Human Right to a Healthy Environment’, (2020) Annual Review of Law and Social Science (Draft) at 10.

Ibid.

The nexus has been also recognised by using a set of procedural rights related to the environment such as the right to access to environmental information and participate in decision making. This path is procedural in nature and belongs to the category of ‘environmental rights’ whereas the other two paths are more substantive and fall into the category of ‘environmental human rights’. For example, the Aarhus Convention or Escazú Agreement which entered into force in 2021 are more focused on the procedural protection of the environment. There seems to be more agreement on the procedural protection of the environment, both at the theoretical and practical level, though the substantive relationship between human rights and environment has remained far from simple or straightforward. See Lewis, supra n 4 at 4; Boyle, ‘Human Rights and The Environment: Where Next?’ (2012) 3 The European Journal of International Law Vol. 23.

Although the right to environment as an individual right has been recognised in the San Salvador Protocol, this protocol does not make this right reviewable by the Inter-American Commission or Court of Human Rights. See Knox 2020, supra n 10 at 84.

The approach adopted by the ECtHR is faced with further challenges. For example, in the case of Article 8(2) of the Convention, the failure to recognise the right to environment can result in giving priority to ‘the economic wellbeing of the country’ over environmental protection. This can be a significant problem especially when it comes to climate change. Moreover, as reflected in Lambert’s report, allowance of a considerable domestic margin of appreciation affects the extent of supervision by the ECtHR. This can reinforce the internal looking character of the greening of human rights path discussed before. See Pavoni, ‘Environmental Jurisprudence of the European and Inter-American Court of Human Rights: Comparative Insights’, in Boer (ed.), Environmental Law Dimensions of Human Rights, (2015) at 69–106; Lambert, ‘The Environment and Human Rights, Introductory Report to the High-Level Conference Environmental Protection and Human Rights’, Strasbourg, 27 February 2020 at 13; PACE, Doc. 9791 ‘Environment and Human Rights, Report of the Committee on the Environment, Agriculture and Local and Regional Affairs’, Rapporteur: Ms Agudo, 16 April 2003 at para 28.

E.g. Öneryildiz v. Turkey, Application No. 48939/99, judgment of 30 November 2004 at para 118. For an overview of the European Court of Human Rights’ judgments on environmental matters, see Council of Europe, Department for the Execution of Judgments of ECtHR, Thematic Factsheet, October 2020.

E.g. Fadayeva v. Russia, Application No. 55723/00, judgment of 9 June 2005 at para 134; Taşkin and others v. Turkey, Application No. 46117/99, judgment of 10 November 2004, Para126; López Ostra v. Spain, App. No. 16798/90, judgment of 9 December 1994 at para 58; Cordella and others v. Italy, Application Nos. 54,414/13 and 54,264/15, judgment of 24 January 2019 at para 174.

See, e.g. Saramaka Peoples v. Suriname, Series C No. 172, judgment of 28 November 2007, para 158; Indigenous Community of Yakye Axa v. Paraguay, Series C No. 125, judgment of 17 June 2005, at para 143.

Lhaka Honhat Association v. Argentina Series C No. 420, judgment of 6 February 2020.

See, e.g. Dubetska v Ukraine Application No 30499/03, 10 February 2011; Di Sarno and others v Italy Application No 30765/08, 10 April 2012; Fadeyeva v Russia, supra n 16; Moreno Gomez v Spain Application No. 4143/02, 29 June 2004; Dzemyuk v Ukraine Application no 42488/02, 4 September 2014; Mayagna (Sumo) Awas Tingni Community v Nicaragua (Merits, reparations and costs) Series C 79 [15] judgment of 31 August 2001; Maya Indigenous Community of the Toledo District v Belize, Case 12.053, Report 40/04, IACHR OEA/Ser.L/V/II.122 Doc 5 rev 1, 727 (2004).

See, e.g. Fadeyeva v Russian Federation, Judgment, Merits and Just Satisfaction, App No 55723/00, ECHR 2005-IV, [2005] ECHR 376; Budayeva and others v Russia Application No. 15339/02, 20 March 2008; Ivan Atanasov v. Bulgaria (application no. 12853/03); Kyrtatos v. Greece, Application No. 41666/98, 22 May 2003.

See, e.g. Çicek and Others v Turkey, Application No. 44837/07, 4 February 2020.

See, e.g. Khan Cement Company v. Government of Punjab, Supreme Court of Pakistan, 2021 SCMR 834; Milieudefensie et al. v. Royal Dutch Shell plc, District Court of the Hague, 26 May 2021; Sacchi et al. v. Argentina, Brazil, France, Germany and Turkey, CRC/C/88/D/104/2019.

See, e.g. Beckerman and Pasek, Justice, Posterity, and the Environment (2002); Gosseries, ‘On Future Generations’ Future Rights, (2008) 16 Journal of Political Philosophy 446, 456; Macklin ‘Can future generations correctly be said to have rights?’ in Partridge (ed.), Responsibilities to Future Generations: Environmental Ethics (1981) 151 at 152.

Knox, supra n 10 at 16.

See, e.g. Lumina, ‘The Right to a Clean, Safe and Healthy Environment under the African Human Rights System’, in Addaney and Jegede (eds.), Human Rights and the Environment under African Union Law (2020) at 25–54.

E.g. 155/96, The Social and Economic Rights Action Center and the Center for Economic and Social Rights v. Nigeria, 15th Annual Activity Report of the ACHPR (2002); African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights v. Republic of Kenya, Application No. 006/212, 26 May 2017 at para 199; SERAP v. Federal Republic of Nigeria, judgment No. ECW/CCJ/JUD/18/12, 14 December 2012.

This individualistic approach is different from the approach adopted by the African Charter. Yet, in the landmark decision, Indigenous Communities Members of the Lhaka Honhat Association v. Argentina (2020), and following its remarkable advisory opinion in 2017, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights goes even beyond the right to environment and recognises the ‘right of environment’ (nature) holding that the right to a healthy environment protects components of the environment, such as forests, seas, rivers and other natural features, as interests in themselves, even in the absence of certainty or evidence about how it affects individual people.

Recommendation CM/Rec(2022)20 of the Committee of Ministers to member States on Human Rights and the Protection of the Environment (Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 27 September 2022 at the 1444th meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies) available at: https://search.coe.int/cm/pages/result_details.aspx?objectid=0900001680a83df1 [last accessed 24 December 2022].

See, e.g. Boyd, ‘Catalyst for Change’, in Knox and Pejan (eds.) The Human Right to a Healthy Environment, (2018) at 18; Report of the Special Rapporteur on the issue of human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment, Human Rights Council 2020, A/HRC/43/53.

See ‘At a Glance: A Universal Right to a Healthy Environment, December’ (2021) European Parliament, available at: www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2021/698846/EPRS_ATA(2021)698846_EN.pdf [last accessed 02 September 2022].

See, e.g. Knox, ‘Constructing the Human Right to a Healthy Environment’, (2020) 16 Annual Review of Law and Social Science 79; Boyd, ‘Catalyst for Change’, in Knox and Pejan (eds), The Human Right to a Healthy Environment (2018) at 25.

Boyd, The Environmental Rights Revolution: A Global Study of Constitutions, Human Rights, and the Environment (2011) at 181.

Atapattu, ‘The Right to a Healthy Life or the Right to Die Polluted?: The Emergence of a Human Right to a Healthy Environment Under International Law’ (2002) 16 (1) Tulane Environmental Law Journal 65. See also Elena Cima, ‘The right to a healthy environment: Reconceptualizing human rights in the face of climate change’ (2022) 21 (1) Review of European, Comparative and International Environmental Law at 38–49.

Gardbaum, ‘Human Rights as International Constitutional Rights’ (2008) 19 (4) European Journal of International Law 749; Knox supra n 10.

Rodríguez-Garavito, ‘A Human Right to a Healthy Environment? Moral, Legal, and Empirical Considerations’, in Knox and Pejan (eds), The Human Right to a Healthy Environment, (2018) 155–68, at 159.

The UN General Assembly, Resolution 37/7 of 10 October 1982.

Handl, ‘Human Rights and Protection of the Environment: A Mildly “Revisionist” View’ in Trindade (ed.) Human Rights, Sustainable Development and The Environment (1992) at 137.

Lee, ‘The Underlying Legal Theory to Support a Well-Defined Human Right to a Healthy Environment as a Principle of Customary International Law’ (2000) 25 Columbia J Environ Law, 283, at 297.

Human Rights Council, forty-third session 24 February–20 March 2020, Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development A/HRC/43/53.

Kant, The Critique of Pure Reason (1999).

Following this report and influenced by that, in 2022, the ‘Strasbourg Principles’ were released. These principles, which are meant to be a uniform restatement of general principles that have emerged in international human rights law in the context of the environment, were drafted by a group of human rights and environmental law experts who were brought together by the Conference ‘Human Rights for the Planet’ held in 2020 at the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. Most of the above criticisms, however, are applicable here too. See ‘The Strasbourg Principles of International Environmental Human Rights Law’ (2022) 13 Journal of Human Rights and the Environment, 195–202.

See Alston, ‘Conjuring up New Rights: A Proposal for Quality Control’ (1982) Am J Int Law 78(3):607; Higgins (1994) Problems and Process: International Law and how we use it. Clarendon, Oxford; Donnelly, In Search of the Unicorn: the Jurisprudence and Politics of the Right to Development, California West International Law Journal 15:474 (1985); Lewis supra n 4 at 97.

Cervantes, Marmolejo and Roeben, Volker and Solis, Reilly, ‘Global Climate Change Action as a Jus Cogens Norm: Some Legal Reflections on the Emerging Evidence’ (2022) 8 Environmental Policy and Law, 359.

Chalabi, supra n 7.

Ibid.

Hamilton, The Political Philosophy of Needs, (2003).

For full details, see Chalabi, supra n 7 at 48–50.

See, e.g. Finnis, Natural Law and Natural Rights (1980); Raz, The Morality of Freedom (1986); MacCormick, Legal Right and Social Democracy, (1982); Kramer, Simmonds and Steiner (eds.) A Debate Over Rights, (1998); Kramer ‘Some Doubts about Alternatives to the Interest Theory’ (2013) 123 Ethics at 245–63; MacCormick, ‘Rights in Legislation’, in Hacker and Raz (eds.) Law, Morality and Society: Essays in Honour of H.L.A. Hart (1977) at 189–209.

For full details see Chalabi, supra n 7 at 50–52.

Ibid. at 56–57.

For full details see ibid. at 45–48.

For details on deficiencies of the capability approach see ibid. at 50–52.

See, e.g. Qizilbash, ‘Sugden’s critique of Sen’s capability approach and the dangers of libertarian Paternalism’ (2011) 58 (1) International Review of Economics 21; Egdell and Robertson, ‘A critique of the Capability Approach’s potential for application to career guidance’ (2021) 21 International Journal for Education and Vocational Guidance 447.

A basic human need is a lack of something (object or process) required for the continued healthy existence of every human being. Whereas meeting primary needs is a matter of life and death, meeting secondary needs is a matter of health or sickness. For more details on the conceptual definitions of need, interest and capability, see Chalabi, supra n 7 at 53–58.

For more details on what ‘valuable items’ mean, see ibid. at 54–56.

Ibid. at 52–60.

Ibid. at 55.

Basic needs are a threshold. Beyond basic needs is where the concept of human wants comes in. The concept of want goes beyond basic needs. It is subjective and refers to desire towards something. People sometimes want things that can contribute to their flourishing or advancement of their society such as becoming a mathematician, painter or ‘doctor without border’, and sometimes want to indulge themselves in ways dangerous to others or their own health such as smoking. For details on the types of wants and their relationship with basic needs, wants, interest and capabilities, see Chalabi, supra n 7.

Jovanovic´, Collective Rights: A Legal Theory (2012) at 111.

E.g. Morauta, ‘Rights and Participatory Goods’ (2002) 22 (1) Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 91at 111.

Hartney, ‘Some Confusions Concerning Collective Rights’ (2015) 4(2) Canadian Journal of Law and Jurisprudence 293 at 310.

Morauta, ‘Rights and Participatory Goods’ (2002) 22(1) Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 91.

Re’aume, ‘Individuals, Groups, and Rights to Public Goods’ (1988) 38 (1) University of Toronto Law Journal 1.

See, e.g. Taylor, Philosophical Arguments (1995) at 137; Taylor, ‘The Politics of Recognition’, in Gutmann (ed.)Multiculturalism (Examining the Politics of Recognition) (1994) at 59.

See, e.g. Miller, The Moral Foundations of Social Institutions: A Philosophical Study (2010); Brett, ‘Language Laws and Collective Rights’, (1991) 4(2) Canadian Journal of Law and Jurisprudence, 347; Buchanan, ‘Liberalism and Group Rights, in Coleman and Buchanan (eds.), In Harm’s Way: Essays in Honor of Joel Feinberg (1994) at 1–15; Haksar, ‘Collective Rights and the Value of Groups’ (1998) 41 (1) Inquiry 21; Jacobs, ‘Individual versus Collective Rights: Aboriginal People and the Significance of Thomas v Norris’ (1991) 21(3) Manitoba Law Journal 618–630; Green, ‘Two Views of Collective Rights’ (1991) 4(2) Canadian Journal of Law and Jurisprudence 315.

See Raz, ‘Human Rights without Foundations, in Besson and Tasioulas (eds.), The Philosophy of International Law (2010) at 321–338; Newman, Community and Collective Rights: A Theoretical Framework for Rights held by Groups(2011); Jovanović, supra n 59; Graham, Practical Reasoning in a Social World (2002); Sheehy, The Reality of Social Groups (2006); May, The Morality of Groups: Collective Responsibility, Group-Based Harm, and Corporate Rights (1987).

Jones, ‘Group Rights’, The Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, Fall edn. (2022), Zalta and Nodelman (eds.) available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2022/entries/rights-group/ [last accessed 20 December 2022].

See, e.g. Raz, supra n 66; Miller, ‘Group Rights’, Human Rights and Citizenship, (2002) 10 (2) European Journal of Philosophy 178.

Jones, Group Rights (2009).

For more details on the distinction between collective conception and corporate conception of collective right see, e.g. Jones, ‘Human Rights, Group Rights and People’s rights’, in Robert McCorquodale (ed.), Human Rights (2003).Some other theorists whose approach to group rights is consistent with what is described here as “collective” include Brett, supra n 65; Buchanan, The Role of Collective Rights in the Theory of Indigenous People’s Rights (1993) 3(1) Transnational Law and Contemporary Problems 89; Jacobs, ‘Bridging the Gap between Individual and Collective Rights with the Idea of Integrity’ (1991) 4(2) Canadian Journal of Law and Jurisprudence 375.

See, e.g. Kymlicka, Multicultural Citizenship (1995); Jones Essays on Culture, Religion and Rights (2020) 53–81.

There is a vast literature on the relationship between individual rights and collective rights. E.g. Jones, ‘Group Rights’, supra n 71; Jones, ibid; Jones, ‘Human Rights and Collective Self-Determination’, in Etinson (ed), Human Rights: Moral or Political? (2018); Buchanan supra n 65; De Feyter and Pavlakos, The Tension Between Group Rights and Human Rights: A Multidisciplinary Approach (2008); Isaac, ‘Individual versus Collective Rights: Aboriginal People and the Significance of Thomas v Norris’ (1992) 21(3) Manitoba Law Journal 618.

See, e.g. Coventry and others v Lawrence and another [2014]; Andrae v Selfridge and Co Ltd [1938] Ch 1, [1937] All ER 255; Cocking v Eacott and Waring [2016] EWCA Civ 140.

Buchanan, supra n 64 at 3.

Buchanan, ‘The Role of Collective Rights in the Theory of Indigenous Peoples’ Rights, (1993) 3 (1) Transnational Law and Contemporary Problems 89.

Trindade, ‘The Parallel Evolutions of International Human Rights Protection and Environmental Protection and the Absence of Restrictions upon the Exercise of Recognized Human Rights’ (1991)13 Revista Instituto Interamericano de Derechos 36, at 66.

Pentassuglia, Minorities in International Law—An Introductory Study, Council of Europe Publishing (2002) 47–8.

See, e.g. Rugby v. Walters (1967); Weston Paper v. Pope (1900); Pennington v. Brinsop Hall Coal (1877); Swindon Waterworks v. Wilts and Berks Canal (1875).

This is the first article in a series on the right to environment. The second one is focused on the right to environment as a global right.

Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 15: The Right to Water (2002) 3.

Van Dyke, Education’s Impact on the Environment, available at: https://conexed.com/2021/04/20/educations-impact-on-the-environment/ [last accessed 7 April 2022]. See also Duque and Gilraine, ‘Coal Use and Student Performance’, Ed working paper No 20–25, available at: https://edworkingpapers.com/sites/default/files/ai20-251.pdf [last accessed 1 March 2022].

Sen, Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation (1981).

Some properties of natural resources and processes have also secondary properties dependent upon some sentient beings such as sound, smell, color, taste, fear.

For conceptual definition of ‘fact’, ‘objective facts’, ‘primary and secondary properties’, ‘ontological objectivity’, ‘truth’ and the distinction between ‘property’ and ‘predicate’, see Bunge, Chasing Reality: Strife over Realism (2006) at 9–33. For a typology of different conceptions of ontological objectivity, epistemological objectivity and semantic objectivity, see Kramer, Objectivity and The Rule of Law (2009) Chapter 1.

For different conceptions of reference, see Bunge Volume 1: Semantics I: Sense and Reference (1974) at 146–154. On epistemic objectivity, see Rescher, Epistemology: An Introduction to the Theory of Knowledge (2003) at 174–187.

Author notes