-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Eamonn O’Keeffe, Military music and society during the French wars, 1793–1815, Historical Research, Volume 97, Issue 275, February 2024, Pages 108–128, https://doi.org/10.1093/hisres/htad027

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars were experienced by the ears as much as the eyes, yet the auditory dimensions of these conflicts have received limited attention from historians. This article interrogates the reach and reception of military music in wartime Britain and Ireland by drawing on a wealth of evidence from memoirs, diaries, press reports and regimental archives. It demonstrates that military bands provided sought-after entertainment at myriad public events and staged open-air concerts for socially diverse audiences. The article interprets martial music-making as an important civil-military interface and a potent form of cultural propaganda: a means of inculcating patriotism and asserting the sonic supremacy of the established order in a revolutionary age. But it also reveals that military music provoked irritation, controversy and distress, not least by generating noise complaints and exacerbating sectarianism in Ireland. The article concludes by considering the role of British regimental music-making in overseas colonies and foreign theatres of operations, arguing that it functioned as a form of soft power that underpinned imperial authority, aided diplomacy and eased relations with local inhabitants. An intrusive symptom of large-scale military mobilization, martial music shaped civilian attitudes and soundscapes while profoundly influencing broader musical culture.

Few who lived in Britain or Ireland during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars could forget the noise. The streets of Edinburgh, one memoirist claimed, echoed with ‘nothing but drumming and fifing’ every afternoon.1 ‘Every town’, the caricaturist George Cruikshank remembered, was ‘a sort of garrison; in one place you might hear the “tattoo” of some youth learning to beat the drum; at another place some march or national air being practised upon the fife’, while twice daily ‘the bugle horn was sounded through the streets’ to summon the volunteers for drill.2 The difference between war and peace was acutely audible in urban centres and at local fairs. One Colchester tailor described the cacophony of drums, fifes and trumpets that ‘again greeted our ears’ after Napoleon’s escape from Elba, renewing ‘all the warlike feelings’ that had dissipated in the brief ‘quiet’ following his abdication.3

Music was perhaps ‘the most far-reaching form of entertainment’ in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, according to Mark Philp, and was critical in the ‘struggle for the loyalty of the British public’ following the French Revolution.4 Yet research on cultural responses to war in this period has largely concentrated on fine art, literature and drama.5 Valuable work has been done on song as a vehicle of patriotic sentiment and radical disaffection, but historians of popular politics are generally more at home with visual symbols and printed texts than the intangible phenomena of music and sound.6 While John Cookson has argued that martial music ‘deserves attention as one of the most important civilian-military interfaces’ in Britain from the late eighteenth century onwards, most studies of wartime society and late Georgian loyalism mention regimental instrumentalists only incidentally or not at all.7 Music historians too have paid surprisingly little heed to martial music; as Jeffrey Richards observed in a study of music and British imperialism, few other genres ‘have been subject to such contempt from musicologists’.8 This neglect mirrors a wider tendency among social and cultural historians to view the military as a peripheral institution – one that was disconnected from wider society and can therefore be safely compartmentalized or ignored.9 By investigating martial music, this article makes an original contribution to a growing body of scholarship that instead emphasizes the breadth of interactions between soldiers and civilians and uncovers the impact of recurrent eighteenth-century warfare on British and Irish life.10

Military music-making, though by no means new to this period, expanded enormously from the outbreak of war in 1793 on account of the drastic enlargement of the land forces. By 1814 more than 20,000 instrumentalists were serving in uniform, not only in the regular army, the fencibles and the militia but in a host of part-time home defence formations, including the yeomanry, local militia and volunteers.11 These musical warriors can be grouped into two main categories. Fifers, drummers and buglers in the infantry, and trumpeters in the cavalry, served a core communications function. Their signals instructed soldiers to rise, eat, work and sleep, and in some cases transmitted commands on the battlefield. But drummers and their analogues also performed more extensive repertoires to provide parade-ground pageantry and improve morale, and in these roles they were joined by the second type of military performer: regimental bandsmen. Military bands were sponsored by a combination of state funding and subscriptions from regimental officers who regarded music as essential to unit prestige. These ensembles featured wind instruments such as clarinets, horns and bassoons alongside percussion instruments inspired by Ottoman precedents, which were often played by Black musicians.12

Rather than focus on the role of music in the military, this article explores the presence of martial music in wider society. The limited research that has been published on military music during the French wars rightly highlights its significance as a recreational amenity and a symbol of state authority but offers assessments of impact that seem imprecise or unconvincing. Patrick O’Connell has contended that militia musicians in Ireland were important in ‘forging and solidifying a sense of identity and loyalty’ among ‘competing political factions’, yet what this identity may have been and how broadly it was shared is not specified, nor is much proof provided of military music’s ostensible ability to shape civilian attitudes.13 Trevor Herbert has been more forthright in arguing that regimental bands inculcated feelings of Britishness among the rural poor. However, his case rests entirely on a handful of accounts written by wealthy listeners and military recruits, who testified to their fascination with martial music but made no reference to its impact on their sense of national consciousness. While contending that regimental music-making was widespread in provincial England, Herbert has also suggested, along with Helen Barlow, that military display became a routine and deliberate element of state and royal ceremonial only in the late nineteenth century.14

Instead of assuming that martial music was an invariable crowd-pleaser, this article interrogates its reach and significance by drawing on an extensive body of primary sources, including more than 100 published and manuscript accounts written by listeners who reflected on military performances. It interprets music as an active and communal medium, which prior to the advent of recorded sound had to be made each time it was heard. More a process than a thing, music was always in some sense participatory, for audiences as well as performers were involved in giving it meaning by interpreting and responding to the tunes they encountered, be it with plaudits or brickbats.15 Yet, as is the case with song and print literature, discerning the influence of music on collective mentalities is not a straightforward task. Music could contribute to the creation of ‘imagined communities’, including nations and empires, by eliciting simultaneous expressions of public feeling.16 At the same time, however, reactions were inherently individualized, depending on a person’s preconceptions and tastes.17 While acknowledging the challenges inherent in gauging reception, this article nonetheless aims to provide a deeper understanding of the place of military music in wartime society and the spectrum of responses it elicited.

Martial music emerges as an intrusive symptom of large-scale military mobilization that was central to the civilian experience of war. Far from comprising a ‘closed musical world’, regimental bands were an integral part of the wider musical ecosystem.18 They provided sought-after entertainment in provincial towns, playing not only at military parades but at myriad public events, including balls and dinners, civic processions, concerts, and church services. Military music was regarded as a potent means of inculcating patriotism, intimidating political dissenters and asserting the sonic supremacy of the established order in a revolutionary age. The performances of drummers and bandsmen enjoyed considerable popularity across society and evoked a variety of affective responses, including feelings of national pride and fondness for the military. Yet drummers and military bandsmen also provoked irritation, controversy and distress, not least by generating noise complaints and exacerbating sectarianism in Ireland. The article concludes by considering the role of military music overseas, arguing that it functioned as a form of soft power that helped to legitimize imperial authority, aid diplomacy and ease relations with local inhabitants.

*

Martial music was a prevalent part of the wartime soundscape: it reminded civilians of the ongoing conflict and the military’s presence in their midst. Although the intensity of this clamour varied over the course of the wars and was far more sporadic in the countryside than in towns, the expansion of the armed forces unquestionably spread military pomp far and wide, causing many English villages, according to an American traveller, to resound with French horns and trumpets.19 Music was also a harbinger of overseas colonization. The wife of Upper Canada’s first lieutenant governor, for example, mentioned ‘the beat of drums and the crash of falling trees’ in her diary and described how regimental musicians playing at Queenston along the Niagara River added ‘cheerfulness to this retired spot’.20 Overheard duty beatings and sounds helped civilians quantify the passing hours and influenced their daily routines. A lodger in Edinburgh was rudely awakened at six o’clock by buglers in the nearby castle, while trial witnesses described events as ‘early in the morning … just after the drums beat’ or recalled going to bed at ‘drum beat’ at Sydney in Australia.21

The ordinary course of military duties occasioned many opportunities for public encounters with martial music. Soldiers paraded with instrumental accompaniment not only in camps and barracks but in streets and marketplaces and on town greens.22 Duty beatings known as the Troop, the Retreat and the Tattoo were performed through the main thoroughfares of garrison communities: fife major John Shipp recalled playing through Colchester twice daily, ‘followed by all the girls and boys in the town’.23 Military custom also demanded that regimental instrumentalists strike up whenever they entered and left a sizeable settlement.24 Thirty buglers and a ‘most excellent band’ of the 95th Rifles, for example, played ‘Over the Hills and Far Away’ through ‘every country village’ on an 1809 march to Dover, while three troops of the 23rd Light Dragoons ‘kicked up an awful row’ during their progress from Chichester to Weymouth seven years later, gathering crowds with bugle calls before breaking into a fifteen-verse song extolling their Waterloo exploits.25 Drummers also drew public notice to official announcements, including the imposition of curfews in Ireland during the 1798 rebellion.26 On taking up new quarters, regiments invariably sent a sergeant and a drummer through town to warn residents that the officers were not liable for debts incurred by their men, a practice known as ‘crying down the credit’.27

Music’s ability to generate public interest proved useful to army recruiters, who relied on drummers, fifers, Highland pipers and trumpeters to compete for attention at bustling marketplaces and fairs. Soldiers enlisted for many reasons, not least economic distress and a desire for travel, but several autobiographers cite the appeal of military music as an important factor in their decision.28 Recruiting officers certainly believed that competent performers were indispensable to their task: a captain of the Breadalbane Fencibles, for instance, noted that the performances of a regimental musician at Dumfries ‘had a great effect in inducing’ men to enlist.29 Music could encourage enrolment even at a distance. One eighteen-year-old farm labourer, seized by ‘a sudden start of patriotism’ on hearing the drum of a Shropshire volunteer company in 1804, chased after the corps for nearly two miles to offer his services.30

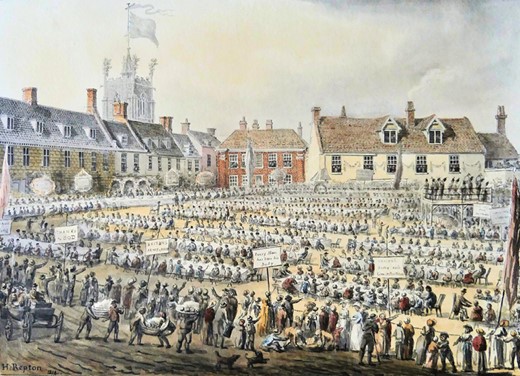

Music was an essential ingredient of the military spectacles that proved tremendously popular with the wartime public, from local field days and mock battles to the colossal Hyde Park reviews of 1803, which saw 27,000 volunteers assemble before hundreds of thousands of onlookers over two days.31 Drummers, trumpeters and band musicians saluted generals and royalty with ‘God save the king’, struck up during inspections and the march-past, and played as their units paraded to and from the ground.32 Interest in military music transcended gender, age, and class (see Figure 1). An eighteen-year-old factory hand visited the militia encampment on Kersal Moor near Manchester every Sunday in 1812, explaining that ‘the bands playing made it a pleasant out[ing]’, while a widow in County Mayo, whose lodgings overlooked the parade ground at Ballina, made a habit of inviting guests round for tea to listen to the martial music.33 The elite ensembles of the Foot Guards proved leading metropolitan attractions for visitors and locals alike, reliably drawing throngs of ‘boys and grown men, gentlemen, vagabonds, [and] maid-servants’ to the changing of the guard in St. James’s Park.34 Even routine parades in market towns attracted throngs on account of the music, sometimes resulting in scuffles as soldiers struggled to hold back the crush of listeners.35 The significance of music for public military displays was amply appreciated by volunteer officers, who carefully choreographed instrumental accompaniment for the formal presentation of their colours and borrowed performers from other corps to increase the splendour of the day.36 The commander of the Dunfermline Volunteers even changed the date of the ceremony to permit the attendance of musicians from the Breadalbane Fencibles, who he hoped would linger long enough to play the violin at the ensuing evening ball.37

![Review of the Northampton[shire] Militia at Brackley, by Thomas Rowlandson, c.1803 (Yale Center for British Art), featuring drummers in the foreground and the regimental band playing on the right.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/histres/97/275/10.1093_hisres_htad027/1/m_htad027_fig1.jpeg?Expires=1750193539&Signature=zc6HbScBuGq273-~VhMdouo7mjcTWMreTCLMQ6yQCghJMvl3YSDnCeAlzS27Gm8YkNN8Npn2K~vTUucUK3~UHN5z0Og8zfzwvpfCqbGtTUcTQoHfjhRD3SwNleqU6hElfoQBYHsJgxsVawg9sxBPju~EdcUW4A-OYV4QgxvUOx7kDGY23ivsuL3L7XKHCC-Gk57nbaCZtdDIzRZWYoW0VKwU3VWeUbvj3VwoBjawIKvtubib1A3I0tVgTISiSNboaLAVA2JFY7mNa01vmG7Dc2llTVNG1ZBRPN83lNJS9A0gfKsdvLxAK48A7PX7-hgiK0ZzBII8uw39ObuOVU-ScA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Review of the Northampton[shire] Militia at Brackley, by Thomas Rowlandson, c.1803 (Yale Center for British Art), featuring drummers in the foreground and the regimental band playing on the right.

As this request for military fiddlers suggests, the social functions of regimental bands were as valued as their contributions to martial pageantry. Officers were keen to fund militia ensembles in the belief that they would enhance genteel gatherings of county society, while aristocratic colonels routinely employed their regimental bands for dinners and fêtes at country houses.38 Military men made inroads with local notables as they moved between postings by organizing social occasions enlivened by their musicians, demonstrating their gallantry and refined manners through dance.39 Bands helped officers court women, who were considered especially receptive to military music’s charms; a lieutenant of the 60th Foot even suggested that his battalion’s band had been formed expressly to ‘please the Jamaica ladies’.40 The attendance of regimental musicians also dramatically augmented the accompaniment available for provincial dances. A visitor to the Bodmin assembly in 1797 noted that the usual blind fiddler had been superseded by the band of the Somerset Militia, who ‘not only occupied half the room, but stunned us with the noise of their drums [and] clarionetts’.41

Military musicians attended a remarkable array of public amusements and commercial entertainments, from horse races, fairs and village feasts to hot air balloon demonstrations.42 The musicians of the Coldstream Guards, dubbed the duke of York’s band after their long-time colonel, not only became a mainstay of London balls but regularly appeared in uniform at Vauxhall Gardens.43 Uniformed ensembles were also difficult to miss at provincial theatres, where they contributed musical interludes or filled the orchestra pit on nights patronized by their officers.44 Such thespian outings did not prevent regimental bands from performing in sacred settings. Military musicians were most important as church singers and instrumentalists in overseas colonies, where there were few alternative sources of accompaniment, but militia bands were also engaged in Irish garrison towns to increase the appeal of both Protestant and Catholic charity sermons.45 The goodwill generated by these public-facing performances is apparent from press reports and diaries praising both regimental musicians and the officers who underwrote them. A Clonmel correspondent thanked the colonel of the Royal Tyrone Militia for permitting its ‘admirable band’ to play during the intervals of a performance of Shakespeare’s Henry IV, describing the gesture as proof of his ‘obliging attentions to promote the gaiety and amusements of this town’.46

Military performers attended a range of communal rituals and ceremonies, contributing to the eighteenth-century growth and elaboration of performative street processions (see Figure 2).47 By attending town banquets and cavalcades that perpetuated civic traditions and marked the installation of new magistrates, military bands helped reinforce social ties among urban elites and publicly emphasized their position to assembled crowds.48 Regimental ensembles routinely solemnized ship launches, colliery and canal openings, and the laying of foundation stones for public buildings, symbolically tying local enterprise to national or imperial authority.49 The music of military bandsmen and recruiting drummers, moreover, conspicuously figured in deferential receptions accorded to prominent visitors, including war heroes and royalty, combining with cheers, cannon fire and the ringing of church bells to create an impression of joyous approbation from the community as a whole.50 Regimental bands were equally audible at the elaborate and well-attended funerals of fallen generals, statesmen and ordinary volunteer soldiers: the burial procession of the poet Robert Burns, formerly of the Royal Dumfries Volunteers, featured cavalry musicians playing Handel’s ‘Dead March in Saul’ in slow time before the bier.51 Landed families hoping to impress tenants and neighbours with their largesse likewise relied on military bands to enhance extravagant revels honouring important rites of passage. In 1799 an agent of the duke of Rutland hired a Sheffield volunteer ensemble for celebrations of the aristocrat’s coming of age at Haddon Hall, which reportedly drew more than 10,000 people; ‘the whole business would have been very flat without music’, he explained.52 Besides catering to the great and the good, regimental bands were widely employed by masonic lodges and friendly societies to attend feast-day meals and announce the progress of processions, helping members celebrate their solidarity and advertise the fraternities to outsiders.53

Francis Dukinfield Astley in Procession as High Sheriff (detail), 1807 (Tameside Museums and Galleries Service: The Astley Cheetham Art Collection), depicting the band of the Manchester and Salford Rifle Corps.

Despite contemporary misgivings about mixing party politics and soldiering, military musicians also participated in election-time rituals and other partisan displays.54 Lord Milton, a Whig candidate contesting Yorkshire in 1807, was welcomed into Halifax for the hustings by ‘a double band of music and the drummers and fifers of the volunteer corps’; other volunteer and militia performers saluted successful parliamentary candidates in Bristol, North Shields, County Mayo and elsewhere.55 Even regular army musicians occasionally participated in the ‘chairing’ celebrations of newly minted M.P.s.56 There are few indications of official efforts to curtail such performances, save for an investigation of the Knightsbridge Volunteers for saluting Sir Francis Burdett with their drums beating during an 1804 by-election. Burdett’s radical credentials undoubtedly heightened ministerial alarm, but the home secretary’s condemnation of the incident as ‘destructive’ to military discipline and ‘the freedom of election’ appeared to censure politicized military displays irrespective of party stripe.57

*

Thus far military music has been considered as a component of public festivities and military display, but regimental ensembles also appeared at concerts, where music itself was the main event. Bandsmen of both auxiliary and professional regiments routinely gave public concerts and used the profits from ticket sales to supplement their military wages. In 1809, for example, a cavalry band of the King’s German Legion organized a musical evening in Ipswich’s assembly room featuring symphonies, string and brass concertos, and an operatic overture.58 Keen to profit from wartime patriotism, civilian concert organizers seasoned their programmes with loyalist and military-inspired pieces, taking care to publicize the involvement of regimental musicians.59 Military bandsmen and musically talented officers collaborated with local performers wherever they were posted, providing ‘a strong reinforcement to the orchestra’ at provincial concerts from Framlingham to Montrose (see Figure 3).60 The composer John Marsh, for instance, relied heavily on martial musicians stationed in Chichester for his winter concert series, and consequently lamented the redeployment of regiments with particularly good bands as ‘a great loss’ to his line-up.61 The number of military musicians concentrated in wartime Cork and Dublin facilitated concerts on an unexampled scale: orchestras of 70 to 150 instrumentalists, incorporating the combined bands of each garrison, played descriptive battle pieces before audiences of thousands, enabling listeners to ‘imagine’ themselves, according to a newspaper review, amidst ‘scenes of danger and awful confusion’ at Alexandria, Trafalgar and elsewhere.62

The Country Concert, by C. L. Smith, 1794 (courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University). This etching depicts uniformed officers and soldiers, including a Black musician, as part of the orchestra.

Most indoor concerts were exclusive occasions, with ticket prices of three shillings or more limiting attendance to the relatively affluent.63 But military musicians also reached wider audiences through free open-air performances. Bands not only played on parade but lingered afterwards to oblige onlookers, performing dance tunes, popular ballads, theatrical songs and selections from fashionable Continental composers.64 An 1801 Portsmouth guidebook listed military band performances on public promenades as one of the town’s principal visitor attractions, while ‘all ranks and denominations’, according to a Presbyterian minister, gathered in ‘large numbers’ to hear regimental musicians playing along the walls of Derry on Sunday afternoons.65 General orders for the garrison of Valletta in Malta even instituted a rota for outdoor concerts, with the bands of the 27th, 44th and Sicilian Regiments each instructed to perform two evenings a week outside the governor’s palace between half past six and eight o’clock (see Figure 4).66

Watercolour by Sir George Whitmore, c.1800–12 (Gloucestershire Archives, D45/F58), depicting a military band playing amidst a multiethnic crowd in the Upper Barrakka gardens in Valletta, Malta.

Military ensembles drew audiences not only due to the wartime vogue for martial ceremonial but because they impressed listeners with their large size, generally good performance standards, and novel sights and sounds. In 1793, for example, a dazzled village innkeeper described the seventeen-strong ensemble of the West Middlesex Militia as the best band he had ever heard, singling out the Black percussionists for their ‘very grand appearance’.67 Music enthusiasts who flocked to public band performances paid close attention to the merits of different military ensembles and evaluated the skills of individual performers.68 A Cork newspaper contributor, writing in 1840, credited Irish militia bands with honing ‘the musical taste of our citizens for which they are still proverbial’; a ‘posse’ of perennial ‘band listeners’ developed their appreciation of fugues, dynamics and assorted aspects of music theory by attending parades and guard mountings in wartime, and ‘from amateurs became performers themselves’.69 Several other nineteenth-century observers echoed the view that the proliferation of regimental ensembles had increased popular interest in music-making, although not all welcomed the development. In 1801 a correspondent of the Gentleman’s Magazine fretted that ‘the number of military bands established in the kingdom’, in tandem with an elite ‘musical mania’, had ‘so much extended a degree of knowledge in musick’ that ‘some discarded soldier, servant, or player, scrapes the fiddle in every parish, and promotes drunkenness, lewdness, and idleness by bringing the lads and girls together to dance, and by teaching other loitering fellows to fiddle also’.70

The public evinced their fascination with martial music-making through widespread imitation. A Londoner complained in 1811 about groups of strolling performers who had acquired bass drums and were playing ‘the loudest species of military music’ through the city’s streets.71 The Turkish percussion instruments introduced to the Coldstream Guards by the duke of York became a fashionable novelty in elite drawing rooms in the late 1790s, prompting wealthy ladies to hire Black musicians of the regiment as instructors on the cymbals and tambourine.72 The vogue for these clamorous instruments, praised for promoting feminine agility and graceful movement, spread beyond the capital; the daughter of a Perthshire minister took tambourine lessons from a military bandsman in Dundee.73 Published editions of military marches were marketed to a burgeoning cohort of amateur female pianists; other regimental tunes gained popularity as dances and were copied into the music books of civilian flautists and fiddlers.74 Caught up in the wartime enthusiasm for volunteering, boys and girls sought to reproduce martial music in pervasive games of military make-believe. Catholic schoolboys in Shropshire, for example, acquired an ex-volunteer drum and formed a band to accompany their imitation regiment.75 Juvenile interest in military music was even recognized and exploited by toymakers: some of the earliest sheets printed by the London publisher William West, who produced paper cut-outs of theatrical characters from 1811, depict the celebrated bands of the 1st and 3rd Foot Guards (see Figure 5).76 Finally, audiences listening to regimental performers were widely known to tap along and move in time to the music, miming military deportments and physically emulating marching rhythms.77 ‘Military manners prevail [in Montreal] as at Quebec’, reported an American visitor in 1817: ‘The rabble flock, in crowds, to regimental parades; and even women, of any appearance, make a point of stepping to a march’.78

![Duke of Gloucester’s [3rd Foot Guards] Band, by William West, 1811 (Houghton Library, Harvard University).](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/histres/97/275/10.1093_hisres_htad027/1/m_htad027_fig5.jpeg?Expires=1750193539&Signature=vFTEq36V8gSAM8CnjeA6Q6QR8wC-LUVoqjQqC1qRRp9A99L2JyJ8SUnRN9czTXT5neRkKvrD3a0Y6~EP3wUhjm4TfZ3hqZGEPIrVFjmdeJIEP~NX-hCPn1qY2s12iPbHOIyqJpw~WgDdepW04HU-AO924pgOrMtiNjWR3b9nWzwY9MzTPwUV-R5hMlyVYkp9lO6PFcRrFqEQaI5cIgck9f4xPG5XxlAoP0fwGK-UTBLdjK3P3~jG0boALVNChZ6xia1aapb~5cdtzG4Gh6zkgkR3FKKkwfKtw9e5Qtiu64mHxNgdJbkV0F3fasfFdIA8z56fmb1cAHvtZcy~zHK5YQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Duke of Gloucester’s [3rd Foot Guards] Band, by William West, 1811 (Houghton Library, Harvard University).

Besides providing popular leisure, musical warriors shaped domestic perceptions of war, nationhood and the armed forces. Most obviously, their performances fed the contemporary ‘pleasure culture of war’, encouraging civilians far removed from the battlefield carnage to view military display as romantic and compelling.79 The forms and functions of martial music became sufficiently familiar to the domestic public to warrant inclusion in a host of satirical caricatures (see Figure 6). Ignominious defeats and dismissals were dramatized as regimental ‘drumming-out’ ceremonies, while the Whig politician Charles James Fox and the journalist William Cobbett were mockingly portrayed as recruiting drummers for political radicalism.80 Just as Jack Tar the everyman sailor symbolized masculine stoicism, the Highland piper became an emblem of Scottish nationhood and military prowess.81 A satirical print of 1803, which celebrated British victory in Egypt by portraying a kilted soldier playing Napoleon like a set of bagpipes, was popular enough to merit reproduction by multiple English manufacturers on commemorative ceramics.82 George Clark, a regimental piper who continued playing on a Portuguese battlefield in 1808 after being wounded in the groin, became one of the most vaunted common soldiers or sailors of the period. The Highland Societies recognized Clark’s valour with trophy pipes and medals; artists captured his likeness in paintings and engravings; newspapers even updated readers on the soldier-celebrity’s later deployments and combat performances.83 The publicity around Clark set a trend for the celebration of battlefield piping, buttressing a romanticized view of Scottish Highlanders as an ancient martial race moved to impetuous bravery by their national music.84 By 1813 the Caithness landowner Sir John Sinclair felt justified in asserting that ‘there is no sound which the immortal Wellington hears with more delight, or the marshals of France with more dismay’ than the notes of a Highland pibroch.85

![Contrasted Drummers, 1793 (Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, Curzon b.2[62]). This satirical print adds a musical twist to longstanding chauvinistic stereotypes, depicting an emaciated Frenchman outmatched by a stocky British bass drummer. A caption references the patriotic song ‘Britons, strike home!’](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/histres/97/275/10.1093_hisres_htad027/1/m_htad027_fig6.jpeg?Expires=1750193539&Signature=0axP3MxnmtX7StY8nNaiYz7DLirYSYeMyFcTMEQIJW9S-0rF196bxUWpXp2jAsNDfUnBx6Y4ZlZB03X6pSRHgZz2dN15nSeED28PzwvD~q8mx2m2q~F0N4Dl04ud-hGrfpM6pK0TzriJG-Bq~hRKkE3WzEM5kStA1vlL9KWkaSGgAp8iVlkFM7I1HHCvqOTF4d9gXG-PblnJWtQQipKImaFuOFs3ZsbysQ3McyimzdnRoR6oTJImnbYgW8nnJ6lA3SvgFVb-ZqZdBjhW7JcyplhAjPUNkxc4-ErMcZajWqqSYeDyxOU8O8wDCSC478EiqUcYpaTD17FA4Usn7p7q~w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Contrasted Drummers, 1793 (Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, Curzon b.2[62]). This satirical print adds a musical twist to longstanding chauvinistic stereotypes, depicting an emaciated Frenchman outmatched by a stocky British bass drummer. A caption references the patriotic song ‘Britons, strike home!’

As the renown of Caledonian pipers suggests, the variety of military instruments, repertoires and performances made the military’s multinational character manifest to domestic audiences. The Roscommon Militia, for example, left the inhabitants of Plymouth in no doubt of their origins by parading through town with their band and drums on St. Patrick’s Day in 1812.86 Soldiers of the King’s German Legion spent Sunday evenings dancing and singing the music of their homeland on the parade ground in Winchester, drawing ‘a vast concourse of spectators’ who were delighted by the excellent band and the ‘novelty of the scene’.87 Yet exposure to unfamiliar music could also strengthen feelings of discordant difference rather than harmonious co-operation between peoples, with disdainful English listeners interpreting the ‘barbarous’ racket of the Highland pipes as evidence of Scottish backwardness.88

*

In an age when loyalists often viewed allegiance to king and country as a personal, emotional attachment and music was widely known to influence feelings and identity, it is hardly surprising to learn that military music was considered a potent form of propaganda.89 Successive invasion threats and the revival of popular radicalism after the French Revolution obliged the British state and the propertied classes, notwithstanding their disdain for democracy, to make unprecedented appeals for mass support.90 The battle of ideas between radicalism and loyalism was waged in newspapers, sermons and public meetings but also through an outpouring of music and song. Commentators such as the singer-songwriter Charles Dibdin recognized music’s ability to excite republican passions in France and argued it could also stir counter-revolutionary sentiment.91 What is more, the political agency of music was recognized and intentionally cultivated by military officers. Posted at Manchester in 1793, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Thornton of the West York Militia organized a regimental band to draw larger crowds to his parades and impress ‘sentiments of loyalty on the minds of the populace, by continually amusing them with airs adapted to that purpose; or engaging them in a chorus, which never fails to raise the smallest spark of British loyalty into a flame’. Thornton could not think of a ‘more effectual exorcism … against the demon of sedition’ than ‘a full chorus of “God Save the King”’.92 Indeed, regimental bands regularly played the patriotic odes of ‘Rule, Britannia!’ and ‘Britons, strike home’ and generally concluded concerts and military reviews with ‘God save the king’.93 The popularity of this last tune, which was praised by one Peninsular veteran as a ‘strong bulwark of the throne’, reflected the monarch’s apotheosis as a focus for patriotic feeling. By the closing years of the Napoleonic conflict, ‘God save the king’ was increasingly described not simply as a national air but as the national anthem.94

Music was a vital feature of the patriotic and regal celebrations that grew in frequency and scale during the final decades of George III’s reign.95 The garrison of Roscrea, County Tipperary, in common with all others in Ireland, marked the monarch’s birthday in 1810 by mustering near the market house and firing the customary three volleys, interspersed by yeomanry trumpet fanfares, drum rolls and renditions of ‘God save the king’ from a militia band.96 Officers across the United Kingdom recognized the importance of dignifying celebratory dinners, reviews and public carousing with appropriate music on the fourth of June: a regimental musician in Lancashire cancelled an engagement in 1805 because his colonel had ‘given strict orders that not one of the band must be absent on that day it being the King’s birthday’.97 Military bands were equally imperative to celebrations of George III’s golden jubilee in 1809, helping foster a joyous atmosphere and accompanying crowds as they sang along to national tunes.98 A dearth of music, conversely, jeopardized the emotional impact: a Liverpool resident believed that civic festivities had been ruined by ‘a woful [sic] want of music’, complaining that the two bands present were unable to enliven the full length of the jubilee procession.99 Regimental performers also helped villages and port towns celebrate news of peace and victory, accompanying open-air dinners and processions or serenading tens of thousands of spectators at effigy burnings of Napoleon (see Figure 7).100 Such patriotic displays relied on the initiative of the landed gentry and urban elites, who rewarded military bands for their efforts with meals and extra pay, but the festivities had undeniable popular appeal.101 The journalist Charles Knight recalled how reports of the Battle of Salamanca prompted immediate nocturnal exultation in Windsor: ‘the great mass of our population’ joined the 29th Regiment on a triumphant march through the streets as its band performed the ‘inspiriting’ strains of ‘The Downfall of Paris’.102

Aylsham Celebration of a Festival for the Peace, 15 July 1814, by Humphry Repton (courtesy of Lady Walpole; photograph by Roger Last), depicting a military band performing on a raised platform before feasting crowds.

Far from being a marginal element of pre-Victorian state pageantry, military music was prominent in lavish national spectacles intended as counter-revolutionary ripostes to the large-scale festivals staged by republican and imperial France.103 The public thanksgiving for naval victories in 1797, which drew up to 200,000 people, featured bands of the Royal Marines, brought in from Portsmouth and Chatham, and the musicians of manifold volunteer corps playing at ‘an interval of every five minutes in the procession’ through London.104 Musicians or drummers of the Foot Guards also regularly appeared at court levées and attended the magnificent installation of Garter knights at Windsor Castle in 1805, which was immediately preceded by the public presentation of silver kettledrums to the Royal Horse Guards.105 Some 28,000 regular and auxiliary troops turned out for Lord Nelson’s funeral the following year, with their bands playing and drummers rolling on muffled instruments before silent crowds. Volunteer musicians also encouraged mourning beyond the capital by performing dirges at locally organized memorials to the fallen admiral in towns such as Darlington and Carmarthen.106

*

Documenting the reach of military music is of course far easier than determining its impact on individual listeners. A wealth of evidence drawn from memoirs, diaries and correspondence does, however, suggest that it could elicit strong emotions, including awe, joy, sorrow and national pride.107 James Silk Buckingham, who witnessed an 1812 review at Gibraltar on the king’s birthday while working as a merchant captain, remembered how ‘overpoweringly grand’ salutes of artillery and musketry, followed by a rendition of ‘God save the king’ by all the military bands present, prompted feelings of ‘patriotism, loyalty’ and ‘pride in British supremacy’.108 Music could also foster positive views of the military among the labouring poor: one farmhand was ‘much delighted’ to encounter a militia band in Buckingham in 1802, and later enlisted as a soldier himself.109 Yet responses to martial performances were diverse and often deeply personal, depending on the instruments, repertoire and context. A visitor to an Irish encampment in 1795 claimed he ‘panted for military glory on hearing the shrill fife and drum’ but an officer’s wife could not avoid crying when listening to Caledonian tunes played by a fife major because they evoked nostalgic memories of her Scottish home and father.110 Disorderly and unaccomplished regimental performers could leave a bad impression, as is clear from the diaries of Nottinghamshire stocking-maker Joseph Woolley: he ridiculed musicians of the local Bunny Volunteers as preposterous and incompetent gluttons ‘laughfd at by all that hard [sic] them’.111 The collective attitudes of crowds are, however, generally difficult to reconstruct with confidence: although the ‘lower ranks of people’ paid ‘profound attention’ to military bands, according to a Franco-American traveller, and were sometimes moved to tears by the music, it is not clear how far such listening experiences influenced their attitudes towards the monarchy, war and the state.112 Audiences could certainly listen with ambivalence, hearing and enjoying martial music while remaining resistant to its political implications or disdainful of individuals honoured by its strains.113 This potential for subversive listening was recognized by John Gamble, an Ulster Presbyterian physician and former military surgeon. Noting that regimental bands ended their performances at a Dublin pleasure garden with ‘God save the king’ and the Irish national air ‘St. Patrick’s Day in the morning’, he described the former tune as ‘a draught which must be swallowed’ and ‘Patrick’s Day’ as ‘the sweetener to it’.114

Although listeners did not necessarily embrace the intended resonance, military music nonetheless deserves consideration as a formidable type of symbolic power. Regimental performances helped the governing elite assert greater control over public spaces and soundscapes, encouraging popular participation in patriotic events and fostering what William Tullett has termed ‘emotional atmospheres conducive to loyalty’.115 The burning of effigies of Thomas Paine across England in 1792 and 1793, sometimes accompanied by recruiting drummers and military bandsmen, was taken by a Cheshire clergyman as evidence of an overpowering anti-radical consensus: ‘Loyalty triumphs in every corner of the kingdom’, crowed the Reverend Reginald Heber, and musicians ‘pervaded every street playing and singing “God save Great George Our King”’.116 Military music aimed to intimidate the discontented by broadcasting the presence of the forces of order, including through targeted ‘church and king’ displays outside the homes of leading radicals.117 A veteran of a Glaswegian volunteer unit raised to counter post-war disaffection in 1819 believed its band and bugles not only heartened loyal listeners but ‘conveyed notes of warning’ to would-be insurrectionists, instructing them to ‘continue still in peace and quietness’.118

The acoustic strength of loyalism may well have encouraged a predisposition for the status quo in an era of intensified political controversy, as Mark Philp has argued.119 But this ascendancy was nonetheless frequently contested, not least through the dissemination of radical ballads and altercations over the playing and singing of ‘God save the king’ in provincial theatres.120 Even French prisoners of war sought to continue the ideological conflict of the 1790s through song, disrupting celebrations of the king’s birthday from their prison hulks and countering the performances of British regimental bands with renditions of ‘La Marseillaise’.121 Moreover, it must be stressed that the popular patriotism that military music appears to have encouraged and amplified was volatile and conditional, tending to coalesce during invasion scares and dissipate amid disenchantment with war and its effects.122 The plebeian inhabitants who listened to a military ensemble outside Cardiff Castle with evident gratification in 1800 may well have joined a demonstration against high food prices the following year. On that occasion, the performance of the Cardigan Militia musicians, who turned out with their comrades to police the protest and played ‘at intervals amidst the noise of men, women and children vociferating’, surely had an altogether more ominous resonance.123

Musical signals were essential for co-ordinating the military’s response to civil disturbances, but the audibility of drums sometimes had counterproductive consequences. The noise might attract additional onlookers instead of dispersing disorderly crowds or draw out intoxicated off-duty soldiers, who then began taking part in street affrays.124 Policing duties made the military unpopular in turbulent manufacturing towns: a yeomanry trumpet major’s attempt to sound the assembly during a Sheffield riot was reputedly curtailed by a well-aimed potato, which knocked out two of his teeth.125 Musical warriors were scorned, mutilated and even killed because of their association with official repression, not least in Ireland, where trumpeters and drummers were tasked with flogging civilians and even executing insurgents during the 1798 rebellion.126 Indeed, the public performances of military instrumentalists provided a focus for popular dissension. The commandant of the Wakefield Local Militia, for example, reported in 1810 that the town’s watermen had long made a sport of striking his drummers and hurling rocks or dead fowl as they beat the evening Tattoo, requiring the deployment of armed escorts; he added that the band of another regiment had recently suffered a similar battering in Leeds.127 These hostile receptions reflected not only political disaffection but also national prejudices and antipathy to particular regiments. Drummers of the Leitrim Militia were ‘most wantonly attacked by the mob’ in Bristol and cursed as ‘damned Irish rebels’ during the Tattoo after an officer of the corps knocked a local boy unconscious for taunting him with an offensive song.128

Nowhere was military music more contentious than in Ireland, where the performance of so-called ‘party tunes’ provoked civil unrest and violence in an atmosphere of heightened confessional division. The most recognizable of these sectarian anthems were ‘Boyne Water’ and ‘Protestant boys’ (also called ‘Lilliburlero’), which eulogized the victories of William of Orange, and ‘Croppies lie down’, which glorified the brutal suppression of the 1798 rebellion. Although many Catholics were prepared to attend celebrations of battlefield triumphs and frequent band performances in public squares, they expressed disgust on hearing party tunes performed by fifers and bandsmen, regarding the melodies as provocations that insinuated Catholic treachery and revelled in their subjugation.129 Militia musicians also appeared in processions organized by the Orange Order, a fledging fraternity dedicated to the defence of Protestant ascendancy. Having initially condoned the Orangemen as a loyalist prop to state authority during the febrile 1790s, officers and government officials later forbade bandsmen and drummers of regular and militia regiments from attending sectarian parades to avoid antagonizing Ireland’s Catholic majority. Yet efforts to moderate the repertoire of the part-time yeomanry, which was closely aligned with the Orange Order and less amenable to government control, were notably less successful.130 As Robert Peel, the chief secretary for Ireland, lamented in the wake of a deadly riot triggered by a yeomanry fifer, there was ‘enough bad blood in Tipperary without those blockheads aggravating it with their party tunes’.131 On the other side of the coin, drummers and bandsmen of the Irish militia unsettled Ulster Protestants by accompanying soldiers to Sunday mass, providing an unwelcome auditory reminder that their security depended on predominantly Catholic regiments.132

Religion also engendered public criticism of military music for violating the sanctity of the Sabbath. In 1802 a Durham resident complained that volunteer drums and fifes were ‘almost incessantly heard in some part or other of this town on a Sunday from nine of the morning till nine at night’, drowning out church bells and encouraging ‘incredible’ numbers of youths to indulge in indecent dancing and singing.133 A preacher in Hull likewise fulminated against Sunday military displays and believed that silencing the regimental music, which he considered the principal attraction, would discourage the masses from indulging in such irreverent recreation.134 Military performances in or near churches were also scrutinized for appropriate solemnity: a Bristol Mirror correspondent protested that a ‘merry and heart-cheering quick-step’ played by fifers and drummers as soldiers left Sunday worship in the city’s cathedral was more suited to ‘a vulgar hop’ at a fair.135 Yet criticism of Sunday band concerts in public squares, unlike later in the century, was generally laughed off by army officers and attracted limited support even among the ordained. When Parson James Woodforde chanced on a Welsh militia band during a Sunday amble in rural Somerset, he clearly had no reservations about their performance, lingering until late in the evening and contributing to a collection for the men.136

Military music drew ire not only on account of religion and politics but also because it disrupted daily life. The din of recruiting drummers and regimental bands distracted letter writers, discomfited the sick and generated a litany of noise complaints.137 A budding Folkestone artillery bugler, for example, alleged that a local baker threatened to ‘break every bone’ in his body if he dared to play again, while a Scottish tenant farmer claimed that the ‘constant clamour’ of sixteen fencible drummers practising near his home had traumatized his wife and caused the death of a cow.138 The military inclination to parade through garrison towns with bands playing at ungodly hours, sometimes simply for a lark, cannot have been well received by sleepless inhabitants; militiamen passing through Salisbury in 1796 kept up ‘an incessant drumming in the middle of the night for two hours’, according to Lord Cathcart, who was reluctant ‘to forbid the noise because they seem to enjoy it’.139 Moreover, distinctive musical signals performed in response to rumoured French landings or Irish insurrections sparked recurrent panic both in urban centres and large swathes of the countryside. A Northumberland farmer recorded villagers’ reactions to one false alarm in 1804: ‘The drums beat to arms, the trumpets sounded, the old women fainted, the young women wept and howled for the loss of their sweethearts,husbands, &c &c &c, the dogs barked, and in short poor Wooler was never in such a state before!’140

Martial music also routinely frightened horses. Experienced riders recognized the need to give soldiers a wide berth as their mounts ‘did not much relish … military noise’, but at least five civilians were killed and many more injured by being trampled or thrown from carriages and saddles after horses were spooked by drumming.141 Concern over skittish draught animals clearly lay behind Dublin garrison orders preventing drummers from practising near roads and canals.142 A visitor to Edinburgh was amazed, however, by the steadiness of cart and carriage horses when passing ‘regiment after regiment with drums and fifes’ in the streets, which he attributed to their prolonged acclimatization to soldiers and their sonic accompaniment in the Scottish capital.143

*

This article has so far explored martial music primarily as an aspect of British and Irish wartime experience, but regimental ensembles were also mainstays of public life in the expanding colonial empire (see Figure 8). By attending theatre performances and tiger hunts or playing on promenades, military bandsmen provided European cultural amenities in overseas settings and facilitated social interactions among colonial elites.144 According to Elizabeth Simcoe, the balls and concerts given by the Royal Fuzileers, invariably featuring the ‘fine performers’ of their band, made its officers ‘very popular’ at Quebec, ‘where dancing is so favourite an amusement’.145 By playing for peace celebrations, saints’ days and royal birthdays, military bandsmen reinforced links with the metropole and fostered an impression of imperial unity.146 Regimental musicians also announced the arrival and departure of colonial governors, publicly underscoring their status as royal representatives.147 The new governor of the Cape Colony ‘had the band of the 81[st Foot] playing at his door’ at Government House and ‘every time he appeared in view, “God Save the King” seemed to be struck up, at least I heard it five times’, reported Lady Anne Barnard in 1800, who could not help but snicker at Sir George Yonge’s rapid transformation from fugitive debtor to exalted proconsul.148 As in the United Kingdom, outdoor band performances drew reliably large crowds, yet the dearth of accounts from listeners of colour inhibits the recovery of attitudes to military music beyond those of white settlers and imperial elites.149 The reports of British observers certainly suggest that regimental instrumentalists intrigued and entertained colonial listeners, from Buddhist clerics to enslaved people. As one officer recalled of the Cape Colony, ‘Whenever a regiment came out, bringing a new supply of music, in two or three days you would hear the slaves whistling all the airs’.150 But military music could also impress and intimidate in a kind of sonic demonstration of coercive imperial authority. The army that welcomed the governor general of India to Malacca in 1811, according to Malayan writer Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, generated an awesome avalanche of music and noise comparable to ‘the sound of the Last Trumpet’ on Judgement Day before an audience of ‘thousands of all races’.151

A Grand Jamaica Ball!, 1802 (Library of Congress), depicting a military band (top right).

Music functioned as a form of soft power abroad: its auditory appeal often seems to have improved relations between British soldiers and foreign populations.152 One officer stationed in Demerara, invited to attend the wedding anniversary of plantation owners in the captured Dutch colony, recalled how the arrival of regimental musicians ‘operated like magic on the household’, rapidly bringing ‘fraus and frauleins’ to every window.153 Recognizing the popularity of military bands with French and Iberian civilians during the Peninsular War, commanders routinely ordered them to perform publicly to thank inhabitants for food and hospitality or to entice Spanish señoras to share a dance after parade.154 On Wellington’s triumphant 1812 entry into Salamanca, military ensembles whipped the crowds into a state of exultation: the ‘electric effect’ of the music, according to an officer present, was ‘impossible to describe’.155 Yet regimental performances obviously did not preclude tensions with local people and could even cause offence. The determination of British battalions to march through Calais with drums beating, bands playing and colours flying after Waterloo caused repeated standoffs with civic authorities, who balked at what they deemed hostile triumphalism.156

Finally, music was a significant element of the rituals of diplomacy. Regimental bands played for balls organized by British consuls and took part in audiences with foreign dignitaries or indigenous chiefs.157 Martial music aurally evoked the anti-Napoleonic coalition, both in the aftermath of Waterloo, when Prussian bands favoured British forces with ‘God save the king’ on the battlefield, and during military reviews attended by allied officers and royalty.158 Regimental music-making, as with grandiose architecture, was intended to impress Indian rulers with British power and cultural prowess; Lord Wellesley, who championed ostentatious spectacle as governor general of India, ‘never rested until he got every man’ of the 10th Foot’s superlative band to join his viceregal entourage.159 The perceived importance of music in representing British interests abroad is amply illustrated by the inclusion of military bands in the Macartney and Amherst diplomatic missions to China. In the event the Chinese court seemed indifferent to European music, but it is telling that Lord Amherst insisted on bringing the musicians over the emperor’s objections because he considered them an ‘essential part of the splendour required’.160 Music itself even became a bargaining chip in international negotiations. British authorities agreed to train a European-style military ensemble for the musically inclined king of Madagascar as part of an 1820 treaty forbidding the slave trade, transporting eight Malagasy boys to Mauritius to study under an army bandmaster.161

*

This article has argued that military music was a valued source of entertainment and pageantry, a prevalent medium of cultural propaganda, and an intrusive everyday reminder of war and its effects. Scholarship on the French wars tends to stress an increasing separation between professional soldiers and wider society, not least because of the widespread construction of barracks, but scrutiny of martial music highlights the remarkable degree to which the military made its presence felt – and heard – in British and Irish streets.162 Indeed, if music, like uniforms, helped military men stand out from the crowd, it also exemplified and encouraged continued connections between soldiers and civilians. Appreciating the reach of military music also has substantial implications for broader narratives of late Georgian musical culture. While the existing literature rightly highlights precocious commercialization and rising consumer demand, it usually overlooks the military’s significance as a major sponsor of instrumental activity and an arbiter of musical taste.163 As Holger Hoock has argued, war and the British state were more important catalysts of cultural activity in this period than is generally supposed.164 Historians of popular music, moreover, have asserted that early wind ensembles were relegated to providing an auditory backdrop to public events, with their performances becoming the centre of attention only with the advent of brass band contests in the later nineteenth century.165 Yet, as this article has demonstrated, military bands were already staging accessible open-air concerts of a generally high standard for large and socially diverse audiences during the French wars. Indeed, the unprecedented prominence of military music-making in wartime is central to explaining the subsequent spread of working-class wind and brass bands, many of which were led by retired regimental musicians and clad in quasi-martial attire.166

Besides revealing the significant cultural impact of military music in an era of prolonged and intensive conflict, this article has explored the political salience of regimental performances. Although recent scholarship presents music primarily as a radical instrument for challenging prevailing power structures, it has been at least as significant as an agent or expression of conformity, as David Kennerley notes.167 The prominence of martial music and patriotic song in royal and civic pageantry, far from being a Victorian ‘invented tradition’, as is often implied, was a well-established Georgian practice.168 Plenty of evidence suggests that individual listeners enjoyed and felt deeply moved by these performances. Wider claims, however, about the impact of all this music on collective mentalities are more difficult to substantiate. As this article has shown, audience responses were neither uniform nor consistently receptive: a melody or drumbeat that was aesthetically pleasing or reassuring to one ear could be irritating, sacrilegious or alarming to another. Contention over party tunes in Ireland, in particular, demonstrates the importance of context and repertoire in determining public reception. In the main, however, regimental performers do appear to have helped bridge divisions between professional soldiers and civilians, improving the military’s image in an era when redcoats were often resented on account of their disorderly behaviour and policing responsibilities.169 Regimental performers collectively comprised a cultural force that wartime radicalism could not match in terms of its public prominence, scale and distribution. Their music helped the governing classes assert acoustic control over public spaces and soundscapes and mobilize crowds to create an impression of mass support for the war and the prevailing social order.170 It therefore proved an important weapon in the arsenal of the British state in an era when the loyalties of the people could not be taken for granted but instead needed to be constantly cultivated and reconstituted.

Footnotes

This article won the 2023 Pollard Prize and was initially presented to the ‘British History in the Long 18th Century’ seminar at the Institute of Historical Research. I am indebted to the seminar participants for their thoughtful questions and comments. My former doctoral supervisors, Bob Harris and Erica Charters, also provided valuable advice and encouragement. I gratefully acknowledge the National Army Museum and the Arts and Humanities Research Council for funding the research which led to the publication of this article.

R. Butler, Narrative of the Life and Travels of Serjeant Butler (3rd edn., Edinburgh, 1854), p. 25.

B. Jerrold, The Life of George Cruikshank (2 vols., New York, 1882), i. 44.

[J. Carter], Memoirs of a Working Man (London, 1845), p. 183; and Oldham Library, William Rowbottom diary, 17 Oct. 1801, cited in J. Uglow, In These Times: Living in Britain Through Napoleon’s Wars, 1793–1815 (London, 2014), p. 290.

M. Philp and others, ‘Music and politics, 1793–1815’, in Resisting Napoleon: the British Response to the Threat of Invasion, 1797–1815, ed. M. Philp (Aldershot, 2006), pp. 173–204, at p. 173.

P. Shaw, ‘Cannon-fever: Beethoven, Waterloo and the noise of war’, Romanticism, xxiv (2018), 255–65, at p. 255. See also G. Russell, Theatres of War: Performance, Politics, and Society, 1793–1815 (Oxford, 1995); and M. A. Favret, War at a Distance: Romanticism and the Making of Modern Wartime (Princeton, 2010).

D. Kennerley, ‘Music, politics, and history: an introduction’, Journal of British Studies, lx (2021), 362–74. For song, see O. Cox Jensen, Napoleon and British Song, 1797–1822 (Basingstoke, 2015); and F. M. Jones, Welsh Ballads of the French Revolution, 1793–1815 (Cardiff, 2012).

J. E. Cookson, ‘Britain’s domestication of the soldiery, 1750–1850: the Edinburgh manifestations’, War & Society, xxviii (2009), 1–28, at p. 26. See, e.g., R. Dozier, For King, Constitution, and Country: the English Loyalists and the French Revolution (Lexington, Ky., 1983); and B. Harris, The Scottish People and the French Revolution (London, 2008).

J. Richards, Imperialism and Music: Britain, 1876–1953 (Manchester, 2001), p. 414.

G. Daly, The British Soldier in the Peninsular War: Encounters With Spain and Portugal, 1808–1814 (Basingstoke, 2013), pp. 4–5; and Cookson, ‘Britain’s domestication of the soldiery’, p. 4.

See esp. C. Kennedy, Narratives of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (Basingstoke, 2013); and S. Conway, War, State, and Society in Mid-Eighteenth-Century Britain and Ireland (Oxford, 2006). For an important earlier contribution, see C. Emsley, British Society and the French Wars, 1793–1815 (London, 1979).

For discussion of the numbers of regimental performers, see E. W. O’Keeffe, ‘Musical warriors: British military music and musicians during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars’ (unpublished University of Oxford D.Phil. thesis, 2022), pp. 14–15.

For further context, see O’Keeffe, ‘Musical warriors’; and T. Herbert and H. Barlow, Music & the British Military in the Long Nineteenth Century (Oxford, 2013).

P. O’Connell, ‘Military music and rebellion, Ireland – 1793 to 1816’, in Music and War in Europe From the French Revolution to WWI, ed. É. Jardin (Turnhout, 2016), pp. 121–37, at p. 121.

T. Herbert, ‘Public military music and the promotion of patriotism in the British provinces’, Nineteenth-Century Music Review, xvii (2020), pp. 427–44; and Herbert and Barlow, Music & the British Military, pp. 215–25.

C. McWhirter, Battle Hymns: the Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2012), p. 2; J. A. Davis, Music Along the Rapidan Civil War: Soldiers, Music, and Community During Winter Quarters, Virginia (Lincoln, Neb., 2014), pp. 14–15; and C. Small, Musicking: the Meanings of Performing and Listening (Middletown, Conn., 1998).

B. Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (rev. edn., London, 2006), p. 145.

D. Rowland, ‘British listeners, c.1780–1830’, Nineteenth-Century Music Review, xvii (2020), 359–79.

R. Golding, ‘Introduction’, in The Music Profession in Britain, 1780–1920, ed. R. Golding (Abingdon, 2018), p. 9.

B. Silliman, Journal of Travels in England, Holland and Scotland (2 vols., New York, 1810), ii. 102. See also G. A., ‘The days of the volunteers’, United Service Journal, July 1838, pp. 330–42, at pp. 337–9; and F. Wilkie, ‘Defensive force of the British Islands’, United Service Magazine, May 1845, pp. 97–110, at pp. 101–2. For the decrescendo in volunteer music-making later in the Napoleonic Wars, see Morning Advertiser, 26 Oct. 1809; and London Metropolitan Archives, CLC/W/LA/15/MS9957/2, Portsoken Ward Armed Association minute book, 28 Apr. 1807.

E. Simcoe, The Diary of Mrs. J.G. Simcoe, ed. M. Q. Innis (Toronto, 1965), pp. 91–2, 104.

Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland (hereafter ‘N.L.S.’), MS. 735, Edward Kerr diary, 6 May 1804; and R. Jordan, ‘Music and the military in New South Wales, 1788–1809’, Journal of Australian Colonial History, xvii (2015), 1–22, at pp. 2–3.

Silliman, Journal, i. 40; Duke of Rutland, Journal of a Tour Round the Southern Coasts of England (London, 1805), p. 155; and D. Herbert, Retrospections of Dorothea Herbert, ed. G. Mandeville (2 vols., London, 1930), ii. 373–4, 393.

J. Shipp, Memoirs of the Extraordinary Military Career of John Shipp, ed. H. M. Chichester (London, 1890), p. 38; and J. Williamson, The Elements of Military Arrangement (3rd edn., 2 vols., London, 1791), ii. 59, 90.

T. Reide, Treatise on the Duty of Infantry Officers and the Present System of British Military Discipline (London, 1795), p. 78.

G. Simmons, A British Rifle Man: the Journal and Correspondence of Major George Simmons, ed. W. Verner (London, 1899), p. 5; and London, National Army Museum (hereafter ‘N.A.M.’), 1978-05-74-1, autobiography of Henry Grove entitled ‘The Ups and Downs of Life’, pp. 170–1, 242.

E. M. H. McKerlie, Two Sons of Galloway: Robert McKerlie, 1778–1855, With His Reminiscences and Journal; Peter H. McKerlie, 1817–1900 (Dumfries, 1928), pp. 58–9.

Standing Orders for Prince William’s [115th] Regiment (Gloucester, 1795), p. 64.

Shipp, Memoirs, p. 23; A. Alexander, The Life of Alexander Alexander, ed. J. Howell (2 vols., Edinburgh, 1830), i. 71; and J. Mayett, The Autobiography of Joseph Mayett of Quainton, 1783–1839, ed. A. Kussmaul (Aylesbury, 1986), pp. 20–5.

Edinburgh, National Records of Scotland (hereafter ‘N.R.S.’), Breadalbane papers, GD112/52/33/10, Captain Lindsay to Adjutant Roy, 18 Apr. 1794; GD112/52/38/19, Captain Ranaldson to Roy, 21 Aug. 1794.

The Heber Letters, 1783–1832, ed. R. H. Cholmondley (London, 1950), p. 151.

Manks Advertiser, 17 Dec. 1808; and Annual Register (1803), Chronicle, pp. 446–53.

N.A.M., 1982-07-9, West Suffolk Militia order book, 2 Aug. 1798; and Morning Chronicle, 11 June 1811.

Manchester, Chetham’s Library, Manuscripts/1/371, Recollections of James Weatherley, p. 12; and E. Ham, Elizabeth Ham by Herself, 1783–1820, ed. E. Gillett (London, 1945), p. 107.

W. MacRitchie, Diary of a Tour Through Great Britain in 1795, ed. D. MacRitchie (London, 1897), pp. 79–96; and L. Hunt, The Town: Its Memorable Characters and Events (London, 1889), pp. 438–40.

Sussex Weekly Advertiser, 26 May 1794; and Norfolk Chronicle, 13 July 1805.

Barnsley Archives, Spencer Stanhope Muniments, SpSt/60565, West Riding Yeomanry, 6 Nov. 1794 orders; and Chelmsford, Essex Record Office, L/U 3/1, Loyal Chelmsford Volunteers minute book, 5 July 1798.

N.R.S., Breadalbane papers, GD112/52/78/1, Major Moodie to Lieutenant Colonel Campbell, 6 Jan. 1798.

Belfast, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (hereafter ‘P.R.O.N.I.’), Abercorn papers, D623/A/136/33, Thomas Knox to marquess of Abercorn, 24 June [1793]; D623/A/145/11, George Vallancey to Abercorn, 6 July 1793; and E. W. Fremantle, The Wynne Diaries, ed. A. Fremantle (3 vols., London, 1935–40), iii. 147, 323. See also Wellington, National Library of New Zealand, MS-papers-8670-020-1, Fanny Chapman diaries, 1808–10, for the summertime activities of the 2nd Somerset Militia band at Weymouth.

M. McCormack, ‘Dance and drill: polite accomplishments and military masculinities in Georgian Britain’, Cultural and Social History, ix (2011), 315–30, at p. 323; and Hibernian Journal, 22 Aug. 1808.

M. Bent, ‘“A “Royal American”’, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research (hereafter J.S.A.H.R.), i (1921), 15–20, at p. 16; Herbert, Retrospections, ii. 339–40, 363, 381–92. For a satirical poem on women’s partiality to military music, see Belfast News-Letter, 19 March 1811.

British Library, Additional MS. 28793, copy of a journal kept by the Rev. John Skinner, 1797, fols. 73–4.

Freeman’s Journal, 11 Sept. 1811; Norfolk Chronicle, 21 Apr. 1810; W. Harrod, The History of Mansfield and Its Environs (Mansfield, 1801), p. 42; and Morning Chronicle, 5 Nov. 1813.

Morning Post, 22 June 1801; and Critical Review, July 1812, p. 51.

Ipswich Journal, 26 Nov. 1796.

M. M. Sherwood, The Life of Mrs. Sherwood, ed. S. Kelly (London, 1857), p. 397; Sydney Gazette, 30 Apr. 1814; Finn’s Leinster Journal, 2 Dec. 1797; and S. O’Regan, Music and Society in Cork, 1700–1900 (Cork, 2018), p. 97.

Morning Post, 10 Oct. 1806. See also C. Powys, Passages From the Diaries of Mrs. Philip Lybbe Powys, ed. E. J. Climenson (London, 1899), pp. 304–5.

L. Colley, Britons: Forging the Nation, 1707–1837 (rev. edn., London, 2005), pp. 225–6; and P. Clark, British Clubs and Societies, 1580–1800 (Oxford, 2000), p. 267.

Carmarthen Journal, 21 Sept. 1811; J. Oakes, The Oakes Diaries, ed. J. Fiske (2 vols., Woodbridge, 1990–1), i. 392; and P. Borsay, ‘“All the town’s a stage”: urban ritual and ceremony, 1660–1800’, in The Transformation of English Provincial Towns, ed. P. Clark (London, 1984), 228–58, at pp. 240–5.

Sussex Weekly Advertiser, 11 July 1814; Morning Advertiser, 1 May 1810; Chester Courant, 1 Jan. 1805; and E. Mackenzie, A Descriptive and Historical Account of the Town and County of Newcastle […] (2 vols., Newcastle upon Tyne, 1827), i. 225.

Reading Mercury, 29 Dec. 1800; A. Gawthern, The Diary of Abigail Gawthern of Nottingham, 1751–1810, ed. A. Henstock (Nottingham, 1980), p. 66; and W. Tullett, ‘Political engines: the emotional politics of bells in eighteenth-century England’, Journal of British Studies, lix (2020), 555–81, at p. 565.

Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure, June 1801, pp. 444–6; and W. Grierson, Apostle to Burns: the Diaries of William Grierson, ed. J. Davies (Edinburgh, 1981), pp. 7–9.

Manuscripts of His Grace, the Duke of Rutland , K.G. Preserved at Belvoir Castle (4 vols., London, 1888–1905), iv. 257–8.

Carmarthen Journal, 3 Nov. 1810; Manks Advertiser, 23 May 1807; and Clark, British Clubs and Societies, pp. 266–9, 327.

A. Gee, The British Volunteer Movement, 1794–1814 (Oxford, 2003), pp. 210–14; and A Report of the Proceedings of the Artizans of Birmingham […] (Birmingham, 1812), p. 35.

Leeds Intelligencer, 18 May 1807 (original emphasis); Bristol Mirror, 18 July 1812; Newcastle Courant, 23 May 1807; and Saunders’s News-Letter, 10 March 1814.

Morning Post, 27 July 1802; and Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, G.A.Warw.b.2, ‘Scrap-Book: a chronicle of the times, a series of controversial election papers, and other articles connected with the city of Coventry, collected by W. Reader’, fols. 175–9. See also E. O’Keeffe, ‘The anatomy of a drum corps: drummers and musicians in the Canadian Regiment of Fencible Infantry, 1803–1816’, J.S.A.H.R., xcviii (2020), 41–57, at p. 54, for a comparable instance in Lower Canada in 1808.

Nottingham, Nottinghamshire Archives, Portland of Welbeck papers, DD/P/6/12/12/16, Lord Hawkesbury to marquess of Titchfield, 27 July 1804; and Kentish Gazette, 27 July 1804.

Ipswich Journal, 6 May 1809.

See, e.g., Sheffield Archives, JC/26/2, Handbill for S. Mather’s 6 Jan. 1812 concert; R. Southey, ‘Commercial music-making in eighteenth century North-East England’ (2 vols., unpublished University of Newcastle Ph.D. thesis, 2001), i. 319–30; and S. McVeigh, Concert Life in London From Mozart to Haydn (Cambridge, 1993), pp. 112–18.

J. Marsh, The John Marsh Journals, ed. B. Robins (2 vols., Stuyvesant, N.Y., 1998–2013), i. 608; J. S. Buckingham, Autobiography of James Silk Buckingham (2 vols., London, 1855), i. 166; Suffolk Chronicle, 18 Aug. 1810; and Caledonian Mercury, 4 Apr. 1793.

Marsh, Journals, i. 542–3, 586, 596; ii. 7, 137; and J. Brewer, The Pleasures of the Imagination (London, 1997), pp. 443–4.

I. M. Hogan, Anglo-Irish Music: 1780–1830 (Cork, 1966), pp. 45–6; O’Regan, Music and Society in Cork, pp. 105–12; Freeman’s Journal, 17 Oct. 1809; and Saunders’s News-Letter, 22 July 1813.

See, e.g., Caledonian Mercury, 4 March 1799.

T. A. Ward, Peeps Into the Past: Passages From the Diary of T.A. Ward, ed. A. B. Bell and R. E. Leader (London, 1909), p. 23; and Exeter, Devon Heritage Centre (hereafter ‘D.H.C.’), 6855L/1/1/6, 1st Devon Militia order book, 1813–16, 2 Aug. 1813. For more on repertoire, see O’Keeffe, ‘Musical warriors’, pp. 211–13.

The History of Portsmouth, Containing Its Origin, Progressive Improvements, and Present State of Its Public Buildings (Portsmouth, 1801), p. 74; and J. S. Porter, Christ’s Dominion Over the Sabbath Asserted (Belfast, 1856), p. 15.

N.A.M., 1972-04-18-1, 2nd Battalion, 27th Foot order book, 31 May 1808.

Letter from W. J. Mattham, 2 July 1793, published by G. Blencowe in Notes and Queries, 18 Aug. 1855, p. 121.

Marsh, Journals, i. 668, 695; and Sydney Gazette, 6 Apr. 1816.

Cork Standard and Evening Herald, 18 March 1840 (original emphasis).

Gentleman’s Magazine, June 1801, p. 492 (original emphasis).

Morning Chronicle, 24 Jan. 1811.

Stamford Mercury, 11 Jan. 1799; W. T. Parke, Musical Memoirs (2 vols., London, 1830), ii. 242; and S. Girling, ‘Clementi and the tambourine’, in Muzio Clementi and British Musical Culture, ed. L. K. Sala and R. H. Stewart-Macdonald (Abingdon, 2019), pp. 164–84.

University of St Andrews, Special Collections, msdep14/1B/2, Jessie Playfair diary, Apr. 1800.

See O’Keeffe, ‘Musical warriors’, pp. 233–7; and K. E. McAulay, ‘Nineteenth-century Dundonian flute manuscripts found at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama’, Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle, xxxviii (2005), 99–141, at, e.g., pp. 113, 123–5.

F. C. Husenbeth, The History of Sedgley Park School, Staffordshire (London, 1856), pp. 109–12. See also K. Gleadle, ‘Playing at soldiers: British loyalism and juvenile identities during the Napoleonic Wars’, Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, xxxviii (2015), 335–48.

G. Speaight, ‘The toy theatre’, Harvard Library Bulletin, xix (1971), 307–13, at p. 312; and Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University, Houghton Library, TS 946.5.5, ‘Duke of York’s band’ (three plates), 26 Jan. 1811; ‘Duke of Gloucester’s band’ (two plates), 16 Apr. 1811.

J. Patterson, Camp and Quarters (2 vols., London, 1840), ii. 269.

J. Sansom, Sketches of Lower Canada, Historical and Descriptive (New York, 1817), p. 233.

Kennedy, Narratives, p. 172; and M. Paris, Warrior Nation: Images of War in British Popular Culture, 1850–2000 (London, 2000), pp. 25–6.

London, British Museum, 1868,0808.6697, ‘Drumming out of the regiment!!’, 1798; 1851,0901.535, ‘Alecto and her train, at the gate of Pandaemonium’, 1791; 1851,0901.1220, ‘Posting to the election, a scene on the road to Brentford, Novr. 1806’, 1806; Bodl. Libr., Curzon b.2[62], ‘Contrasted drummers’, 1793; and N.A.M., 1975-12-114, ‘Winging a shy cock’, 1808.

For Jack Tar, see R. McGregor, ‘The popular press and the creation of military masculinities in Georgian Britain’, in Military Masculinities: Identity and the State, ed. P. Higate (Westport, Conn., 2003), pp. 143–56, at p. 146.

Bodl. Libr., Curzon b.22(60), An Old Performer Playing on a New Instrument, 1803; and D. Drakard, Printed English Pottery (London, 1992), pp. 199–200.

The National Archives of the U.K., WO97/831/53, George Clark discharge papers; P. Watt, ‘The Highland Society of London, material culture and the development of Scottish military identity, 1798–1817’, Historical Research, xciv (2021), 351–79; Caledonian Mercury, 29 June 1809, 31 July 1815; Morning Herald, 19 Sept. 1810; and Hereford Journal, 11 Dec. 1811.

T.N.A., WO1/199, Sir Thomas Graham to Lord Bathurst, 15 Jan. 1814; Edinburgh Magazine, Nov. 1817, pp. 399–400; and D. Macdonald, A Collection of the Ancient Martial Music of Caledonia (Edinburgh, ?1822), pp. 4–5. See also H. Streets, Martial Races: the Military, Race and Masculinity in British Imperial Culture, 1857–1914 (Manchester, 2004).

Caledonian Mercury, 31 July 1813 (original emphasis).

Exeter Flying Post, 19 March 1812.

Salisbury and Winchester Journal, 8 Sept. 1806.

J. L. Panter, ‘The early life of a civil servant’, Blackwood’s Magazine, Sept. 1946, pp. 145–53, at p. 152; J. Carr, Caledonian Sketches; or a Tour Through Scotland in 1807 (London, 1809), pp. 176–81; Gawthern, Diary, p. 146; and W. Gibney, Eighty Years Ago, or the Recollections of an Old Army Doctor, ed. R. D. Gibney (London, 1896), p. 131.

M. McCormack, ‘Rethinking “loyalty” in eighteenth-century Britain’, Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, xxxv (2012), 407–21, at pp. 417–18; and K. Barclay, ‘Sounds of sedition: music and emotion in Ireland, 1780–1845’, Cultural History, iii (2014), 54–80.

D. Eastwood, ‘Patriotism and the English state in the 1790s’, in The French Revolution and British Popular Politics, ed. M. Philp (Cambridge, 1991), pp. 146–68, at p. 150.

D.H.C., Sidmouth papers, 152M/C1803/OZ/343, Charles Dibdin to Henry Addington, 4 July 1803; N. J. Desenfans, Descriptive Catalogue […] of Some Pictures (3rd edn., 2 vols., London, 1802), i. 28–9; Jones, Welsh Ballads, p. 1; and M. Philp, Reforming Ideas in Britain: Politics and Language in the Shadow of the French Revolution, 1789–1815 (Cambridge, 2014), pp. 233–4.

T. Thornton, An Elucidation of a Mutinous Conspiracy Entered Into by the Officers of the West York Regiment of Militia (London, 1800), pp. 78–9. (emphasis in original)