-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Desire Alice Naigaga, Jennifer Kavanagh, Ailbhe Spillane, Laura Hickey, Katherine Scott, Janis Morrissey, Shandell Elmer, Hannah Goss, Celine Murrin, Using co-design to develop the Adolescent Health Literacy Questionnaire for adolescents in Ireland, Health Promotion International, Volume 39, Issue 1, February 2024, daae009, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daae009

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Health literacy measurement studies are important for the success of health promotion efforts targeting adolescents. However, the majority of health literacy measurement tools were originally developed for adult populations and may not be reflective of health literacy in the context of adolescence. The present study sought to co-design a health literacy questionnaire and vignettes for adolescents in Ireland aged 12–18 years. This article describes the qualitative phase of the study. In 2019–2021, eight adolescents from the Irish Heart Foundation’s Youth Advisory Panel participated in two concept mapping workshops during which they defined healthy living. Results of the thematic analysis indicated that adolescents defined ‘healthy living’ as a life that was balanced, prioritizing mental health and sleep. According to their definition, healthy living was comprised of six main constructs, namely, knowledge; sources of quality health information; facilitators and barriers; influence of others; self-efficacy, self-management and resilience; and citizenship and communication. These constructs were used to develop vignettes and items for the Adolescent Health Literacy Questionnaire (AHLQ). These were tested on a sample of 80 adolescents to check whether the respondents understood the items and vignettes as intended. Results of the nine cognitive interviews indicated that the adolescents understood the content of the 10 vignettes and 41 items. While the vignettes and AHLQ were developed with Irish adolescents, the approaches taken can be generalized to adolescents living in other countries. This will allow for the development of tailored and relevant solutions for health literacy development and health promotion for this sub-population.

This study used a grounded approach to develop from adolescents’ perspective, health constructs that informed the development of a new measure of adolescent health literacy.

The unique constructs of adolescents’ understanding of healthy living will inform the development of future targeted health promotion actions.

This study exemplifies how adolescents can be actively engaged in health literacy participatory research using co-design methodology.

The new health literacy measurement tool has applicability to the evaluation of future health promotion efforts among Irish adolescents.

BACKGROUND

Health literacy research has grown exponentially over the past two decades. Paradoxically, as its scope and breadth has expanded, it has become apparent that children and young people’s specific assets, characteristics, needs and vulnerabilities remain poorly understood and captured in most health literacy concepts owing to the focus on adult populations (Bröder et al., 2017). As such, the critical role of early-life stages has been overlooked, including elements such as the formation of health behaviors and the mechanisms that lead to the development and maintenance of health throughout the life course (Borzekowski, 2009; Patton et al., 2016). Nevertheless, there is growing interest in the field to increase young people’s participation and engagement with health literacy, and position health literacy as an asset for citizenship, social responsibility, and solidarity (Bröder et al., 2020; Paakaari and Okan, 2020).

Health literacy ‘represents the personal knowledge, confidence and comfort-which accumulate through daily activities and social interactions and across generations-to access, understand, appraise, remember and use information about health and healthcare, for the health and wellbeing of themselves and those around them’ (WHO, 2022). Nutbeam’s (2000) classification of health literacy into three cumulative levels—functional, interactive and critical health literacy—provides a model that makes it possible to see the impact that skill-level differences may have on the health decisions and actions that individuals take (Nutbeam, 2000; Nutbeam and Lloyd, 2021). Functional health literacy describes basic-level skills that make it possible for individuals to obtain relevant health information from different sources and apply that knowledge to a range of prescribed activities (Nutbeam and Lloyd, 2021). Interactive health literacy describes more advanced literacy skills that can be applied by individuals to extract health information and derive meaning from a variety of forms of communication; to apply new information to changing circumstances; and to engage in interactions with others to extend the information available and make decisions (Nutbeam and Lloyd, 2021). Critical health literacy involves the use of higher level cognitive and social skills to analyze health information; to understand and exert control over social determinants of health; and to engage in collective action for health (Chinn, 2011).

Translation of health literacy research into practice and policy that benefits adolescents requires valid and reliable assessment, and the past decade has seen an increase in the number of health literacy assessment instruments targeting children and adolescents. However, the level of participation by children and adolescents in the development of these instruments is limited and often restricted to postdevelopment pretesting. In so doing, the views of the target group as the holders of knowledge and experiences are not considered, thereby negating their contribution to the conceptualization underlying these instruments (Detmar et al., 2006; Roberts et al., 2009; Okan et al., 2018; Osborne et al., 2022). Moreover, by disregarding the input of the target group during development, instrument authors inadvertently ignore the crucial role that context plays on the application of health literacy capacities (McKenna et al., 2017; Osborne et al., 2022).

In order to advance health literacy research in adolescents, it is essential to elicit their understanding of health, identify their health literacy needs through measurement, and then devise solutions to address these health literacy needs. This article describes the steps undertaken to explore adolescents’ understanding of health and the development of a health literacy assessment instrument for Irish adolescents aged 12–18 years. This work is part of the Adolescent Health Literacy Project that was funded by the Irish Heart Foundation and registered as a World Health Organization (WHO) National Health Literacy Development Project (World Health Organization, 2022).

METHODS

The study used a mixed methods study design applying co-design research approaches (Ospina-Pinillos et al., 2019; Slattery et al., 2020), specifically workshops and focus groups, to actively engage adolescents in revealing their knowledge, understanding, views and priorities related to health literacy. The development of the Adolescent Health Literacy Questionnaire (AHLQ) was comprised of three phases: conceptualizing adolescent health literacy; quantitative pilot of the draft questionnaire; and national rollout of the AHLQ to adolescents in Ireland. For the detailed protocol of the study, see Spillane et al. (2020). The present article focuses on the qualitative development of the questionnaire and vignettes, which occurred in the first phase. The objectives of this phase were two-fold: to understand what healthy living means to adolescents and to explore their health literacy needs and potential domains of the AHLQ.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval to conduct this study was granted by University College Dublin Human Research Ethics Committee-Sciences (LS-20-08) in March 2020. Following the coronavirus disease (Covid-19) pandemic, revised ethical approval was granted in March 2021 to accommodate remote research (LS-21-24). Ethical approval to engage the adolescents in the co-design workshops was also granted prior by the Dublin City University (DCUREC/2019/053) in March 2019. All procedures followed were in accordance with the principles as outlined in the Helsinki Declaration. All the facilitators were Police vetted before the study and fulfilled the legal requirements of the Republic of Ireland permitting them to conduct research with children (Office of the Auditor General, 2012). Prior to the commencement of study activities, the parents or guardians of the participants gave written parental consent, which was then followed up by written participant assent. In addition, the participants gave verbal assent before the start of any focus group or online consultation.

Participants

The adolescents who participated in the development of the items in the AHLQ and vignettes were recruited from the Irish Heart Foundation’s Youth Advisory Panel (YAP), which was established by the Irish Heart Foundation to ensure that the voice of adolescents was included in its research, advocacy and program development processes (Irish Heart Foundation, 2023). Membership to the YAP is voluntary and backed up by parental or guardian consent. The role of the advisory group in this study was to participate in the concept mapping, domain specification and development of questionnaire items and vignettes (Daley, 2004; Rosas, 2017). The researchers contacted the YAP through the Irish Heart Foundation and interested members filled out expressions of interest. The adolescents and their parents were given project information sheets and briefed on their role in the project. Both parents and adolescents gave written informed consent and assent, respectively. The advisory group comprised of eight adolescents, four boys and four girls, between the ages of 12–18 years.

In the later stages of development, a sample of 80 adolescents aged 12–17 years attending nine post-primary schools (also known as secondary schools) across Ireland participated in the focus groups during cognitive pre-testing of the draft AHLQ items and the vignettes. Participating schools were contacted from a list of secondary schools and invited to take part in the study. Informed consent was sought and given by school principals on behalf of their schools, parents and guardians and also informed assent by the adolescents who participated. Emerging evidence supports the inclusion of participants early on in the development of novel instruments (Osborne et al., 2013). The use of co-design methods in health research is an effective and meaningful approach to achieve more applicable and acceptable research materials for end users (Beauchamp et al., 2017). From a theoretical perspective, including adolescents in the development process aligns with sociological paradigms that situate children as active agents in the construction of their own social lives and ‘not just passive subjects of social structures and processes’ [(James et al., 1998), p. 8].

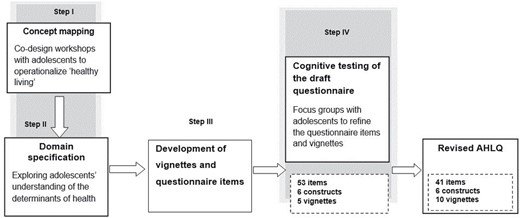

Procedure for questionnaire development

In this study, conceptualizing health from the perspective of adolescents meant placing them at the center of understanding their contemporary lived experiences about healthy living. To achieve this, the study applied qualitative approaches including co-design workshops (Ospina-Pinillos et al., 2019), concept mapping exercises (Daley, 2004), group interviews (Ho, 2006; Adler et al., 2019) and vignettes (Barter and Renold, 2000). The steps undertaken in the qualitative development of the AHLQ are shown below (Figure 1).

The steps undertaken in the qualitative co-design of the Adolescent Health Literacy Questionnaire.

Step I: Mapping the concept of healthy living.

In October 2019, eight adolescents (four boys, four girls) from the YAP participated in two co-design workshops aimed at exploring how they defined healthy living. In the first workshop, the ‘Celebrity Challenge’, the facilitators used images of both local and international celebrities to stimulate conversation about health-related attributes of their lifestyles. There is evidence that media figures, particularly celebrities, influence how adolescents may perceive and define different attributes of healthy living (Chung et al., 2021). Using culturally relevant concepts that participants are familiar with can improve engagement during participatory activities (Bowen et al., 2013). The facilitators used prompts to engage the participants in conversations about each celebrity. These included questions about identity (e.g. what is she famous for?), critical thinking (e.g. has he had an easy or hard life?), body image and belonging. The content used during this workshop was developed based on feedback from previous engagement with adolescents, which revealed what health-related attributes they pay attention to in relation to celebrities (unpublished data).

During the second workshop, the adolescents were put into three groups and tasked with describing what they associated with the hashtag #LivingYourBestLife. To do this, each group searched for images that portrayed what #LivingYourBestLife meant to them on Pinterest, which is an image-sharing social media platform commonly used by adolescents (Fung et al., 2020). They then created Pinterest boards reflecting the associations between the images selected. All group discussions during the exercise were audio recorded using a Dictaphone to capture the thought process during image selection. Following this, the facilitators used prompts to stimulate discussion about the Pinterest boards created. These included questions about the group’s consensus on what the hashtag meant (e.g. what does living your best life look like?), questions that sought out their reasoning behind the selection of the images on the Pinterest boards (e.g. how do the images selected reflect your definition of living your best life?) and questions on associations between the different images selected (e.g. how are the different images selected related with one another and your definition of #LivingYourBestLife?).

Step II: Conceptualizing adolescents’ understanding of healthy living.

The findings of the two co-design workshops were then used to create five storyboards to explore participants’ understanding of healthy living. Storyboarding is a creative technique used in participatory qualitative research to draw meaning from the perspectives of participants’ experiences (Pittaway and Bartolomei, 2012). The facilitators identified common aspects from the Celebrity challenge and Pinterest activity that prompted ‘health’-related words, topics, images or ideas from participants. The facilitators used poster boards and post-it notes to map relevant concepts together with iterative feedback from the youth participants. This allowed for the concepts relating to health to be viewed from a youth perspective. Therefore, the most salient aspects of health were included in the storyboards. Using these storyboards, the participants discussed situations relating to themselves or others that involved these topics. The facilitators asked the participants to consider what adolescents need to live a healthy life and what changes they need to make to achieve a healthy life, identify any barriers to these changes and suggest how they could overcome these barriers. For example, having identified sleep as an important aspect of healthy living, the participants were asked what changes they may need to make in order to get more sleep, what barriers they may face in trying to get more sleep and how they think they could overcome these barriers. The facilitators wrote down the response statements on post-it notes, which the participants sorted into clusters according to similarity. These clusters were then organized into broader constructs reflecting the underlying aspect of the clusters identified. For example, clusters denoting the value of influence of friends, family, social media on adolescents’ health-related actions or decisions, were classified as influence of others. The researchers named the six emergent constructs as follows: knowledge, sources of quality health information, facilitators and barriers, influence of others, self-efficacy, self-management and resilience; and citizenship and communication.

Step III (a): Development of questionnaire items.

The domains identified in Steps I and II were used to develop the questionnaire items and vignettes concurrently through two online focus groups with participants from the YAP. The researchers designed a matrix with the six constructs (vertical) and the aspects of healthy living as identified by the participants (horizontal) to ensure that all the salient aspects were included in the questionnaire items and vignettes to be developed. This was an iterative process, which was conducted within the research team. They developed a guide for use in the focus groups, comprised of open-ended questions, probes and direct questions. These guide questions were structured to reflect health literacy competencies (access, understand, appraise, remember and use) that adolescents need to interact with health information related to the six constructs that the adolescents considered important and or indicative of healthy living. For example, regarding sleep, as an aspect of healthy living; participants were asked ‘Do you know how much sleep is recommended for you to get each night?’ This direct question sought to ascertain what knowledge the participants had about sleep recommendations. This was then followed up by ‘Do you meet these guidelines? Is it easy or difficult to meet them?’ This probe stimulated the participants to identify any facilitators and/or barriers to applying the knowledge they have about this aspect of healthy living. These facilitators/barriers were then presented as response options for the emergent draft question relating to what actions adolescents can take to ensure that they get the recommended amount of sleep per night.

Bloom’s taxonomy was used to guide the writing of the questionnaire items and their response options (Osborne 2013). The cumulative hierarchy of the six cognitive process dimensions in Bloom’s taxonomy, namely, remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating and creating, describes the increasing progression in complexity of cognitive aspects of learning, skill acquisition and performance (Chan and Kaufman, 2011). Item distribution was guided by a ledger against which the researchers mapped the draft questionnaire items and vignettes by using the levels of health literacy as described by Nutbeam (2000) against the cognitive processes of Bloom’s taxonomy. This ensured that items and response options to the items covered a broad scope of health literacy measurement. Accordingly, items describing remembering and understanding were related to functional health literacy; items that involved analyzing and evaluating were distributed to interactive health literacy; and those items requiring the use of the higher order cognitive process of creating and applying were distributed to the critical health literacy level. The emergent draft AHLQ was composed of 53 items scored on Likert-type response scales, with three to five response options.

Step III (b): Development of vignettes.

The present study developed local context vignettes to explore how adolescents may interact with health information in real-life situations. In adolescent health literacy research, the use of vignettes has been shown to be effective in enabling adolescent participants to freely discuss potentially sensitive health topics, such as lifestyle practices, and elicit multiple perspectives on situations using relevant and realistic characters (Smith et al., 2022). Vignettes are described as short stories about hypothetical characters in specified circumstances to which the interviewee is invited to respond to those situations (Erfanian et al., 2020), and they are useful in collecting situated data on group values, beliefs, and norms of behavior (Barter and Renold, 2000; Jenkins et al., 2010).

Based on the constructs identified in Steps I and II, the researchers developed vignettes reflecting instances in which the character displayed high levels of the construct and low levels of the construct. For each vignette, we used Bloom’s taxonomy to guide the development of the response options reflecting the different levels of cognitive processes, namely, remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating and creating. To check whether the scenarios described in the vignettes were relatable to the peers that they represented, the facilitators conducted online consultations with the eight adolescents from the YAP who had taken part in the co-design workshops (Steps I and II) before the Covid-19 pandemic. To achieve this, the facilitators used a discussion guide consisting of prompts, direct questions and open-ended questions (e.g. what would you do if you were in the same situation as the character?). This made it possible to identify any potential problems with the wording in the scenarios and solicit suggestions from the participants on how best to revise them. Each of the characters in the vignettes was described using non-binary names and pronouns (they/them) to ensure inclusion.

Step IV: Cognitive testing of the draft questionnaire.

When refining questionnaire items, it is important to understand whether the items measure what the researchers intend and that the respondents correctly interpret and understand the items (Collins, 2003; Shiyanbola et al., 2019; Osborne et al., 2022). In the present study, the purpose of cognitively testing the draft questionnaire items and vignettes was to identify items or vignettes that did not resonate with the respondents’ lived experiences and was not consistent with the intended construct to be measured. This was achieved by pretesting the draft questionnaire items with a sample of eighty adolescents through nine online focus groups in October 2021. The 38 boys and 42 girls attended nine secondary schools in County Dublin, were between the ages of 12 and 17 years old and were enrolled in the first year through to fifth year. Only one of the nine schools was classified as being located in an area considered to be of relative educational disadvantage as per the Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools (DEIS) indicator. The topic guide used by the facilitators included open-ended probes and direct questions about the items and vignettes. The participants were asked to identify any items or vignettes that were either confusing or difficult to understand and, where necessary, to suggest alternative language to improve the item or vignette content. After each focus group, the facilitators used the participants’ feedback to revise any difficult wording and to merge any items the participants considered very similar in meaning. These revisions were also captured in the topic guides. The focus groups were repeated until no further changes were suggested to the wording of the items and vignettes. The resultant AHLQ consisted of 41 items and 10 vignettes.

Thematic analysis of workshop and focus group data

Three researchers participated in different stages of the analysis using NVivo software and followed the six-step sequence for inductive thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke to identify, analyze and report repeated patterns (Terry et al., 2017). First, the researchers familiarized themselves with the data by reviewing the observation notes and transcripts of the audio recordings from the sessions with the adolescents (co-design workshops and focus groups). Following this, they coded the same transcripts, discussed the emergent codes and developed a codebook that described the meanings and patterns observed in the dataset. The next step was theme development during which one researcher combined the codes into broader candidate themes. During the review and definition of the themes identified, the researcher rigorously consulted the entire database checking that each of the candidate themes identified captured all the key information related to the underlying concept of how health literacy is expressed in the daily lives of adolescents. The final step was a compilation of findings from data analysis, including data extracts as illustrative examples of how adolescents conceptualize health literacy based on their definition of healthy living.

RESULTS

Presented first are the findings of how the adolescents defined healthy living (Steps I and II) followed by the development of the vignettes and items of the AHLQ (Steps III and IV).

A healthy life is ‘balanced’

The participants described healthy living as having a ‘balanced’ lifestyle. The main themes identified were physical well-being, described as working out or doing some sort of physical exercise; mental health, described as having an outlet for stress and knowing when to give yourself a break; eating healthy, which they associated with consuming fewer highly processed and ultra-processed snacks and drinks; and prioritizing rest, especially sleep.

Living with balance, including healthy eating, exercise and sleep along with not much stress. I think that’s what a healthy lifestyle means. And also having fun in life, like having outlets. (Female, aged 16).

A healthy life prioritizes mental health

Of the components of healthy living identified, mental health was elaborated upon the most, suggesting its centrality to how adolescents define healthy living. Four sub-themes emerged; the link between mental health and social media, the link between mental health and physical health, the individual and social influences on mental health, and the link between food choices and mental health.

The link between mental health and social media

Adolescents associated continuous use of social media with negative consequences on one’s mental health. They believed that comparison with influencers and others on social media has the potential to create and/or aggravate negative aspects of mental health such as low self-esteem.

The link between mental health and physical health

That mental health may influence one’s physical health, and vice versa. Adolescents described scenarios, suggesting that mental health may have a positive influence on physical health.

If you have good mental health, then I think you would have the motivation to do some physical activity. It is all connected. (Male, aged 17).

Others regarded physical health, specifically physical activity, as beneficial for one’s mental health.

It’s good for your mental health to be active. (Male, aged 13).

The individual and social influences on one’s mental health

From the discussions, it was apparent that adolescents recognize that mental health is shaped by both positive and negative influences at intrinsic and extrinsic levels. The intrinsic influences presented were particularly associated with one’s use of social media and linked to emergent negative self-esteem. Conversely, external influences by family and friends were both described as positive and negative. A positive example is ‘trust’, which was associated with being able to share concerns about one’s life with family and parents. Negative examples included terms like ‘judgment’, which denoted fears about seeking and acting upon health information, especially around peers and the fear of offending peers facing mental health challenges. Respondents used the terms ‘stigma’ and ‘taboo’ to describe the broader systemic influences about their mental health and discussing or seeking help for mental health issues.

The link between food choices and mental health

Adolescents associated positive mental health with being able to make different food choices that make one ‘feel good’. Sub-themes about using treats and snacks when stressed as a coping mechanism and minimizing food restrictions in times of high stress were also noted in the findings. Nevertheless, the adolescents also acknowledged that healthy eating played an important role in one’s mental health.

Eating healthy food all the time is good for your mental health as well. (Female, aged 15).

A healthy life includes getting enough sleep

Although adolescents described understanding the relevance of getting ‘enough’ sleep, the majority acknowledged that it was difficult to prioritize sleep. Time constraints, busy school schedules and lack of self-control were continuously mentioned as barriers to getting enough sleep. Phone use through the night was highlighted as one of the reasons that adolescents do not prioritize sleep at night, instead preferring to stay up playing games with friends online rather than sleeping for 8 h. Conversely, adolescents only prioritized getting enough sleep in a few situations, such as when they had a test or an important sports match the following day. From a broader perspective, adolescents recognized that compared to the other aspects of healthy living, sleep was not as prioritized, which resulted in the norm becoming less than the recommended hours of sleep.

I wouldn’t say people think about it (sleep) as much as diet, or exercise, as something that needs to be done. But if someone is getting like five or six hours of sleep a night, it is going to affect them at school. (Female, aged 16).

Results from the qualitative development of the AHLQ (Steps III and IV)

Analysis of the concept mapping data and focus groups yielded six main constructs, which were used to develop the AHLQ items and vignettes. These constructs were as follows: knowledge; sources of quality health information; facilitators and barriers; influence of others; self-efficacy, self-management and resilience; and citizenship and communication.

Item and vignette distribution within the health literacy constructs in the AHLQ

Cognitive testing of the draft AHLQ resulted in item reduction from the original 53 items to 41 items. The items that were removed were based on feedback from the focus groups during group debriefing. These were items that were ‘difficult to understand’ for all the respondents, especially those that were younger. Items that were ‘too similar’ making it challenging for the respondents to differentiate. The remaining items were distributed across the six constructs as follows. The construct with the highest number of items was ‘Knowledge’ with 16 items, followed by ‘Sources of Quality Health Information’ with 9 items, ‘Self-efficacy, Self-management and Resilience’ with 7 items, ‘Facilitators and Barriers’ with 4 items, ‘Citizenship and Communication’ with 3 items and lastly, ‘Influence of Others’ with only 2 items.

The 10 vignettes developed were distributed as follows: with the exception of one construct, ‘Knowledge’, all constructs of the AHLQ had vignettes portraying central characters with low and high levels of health literacy within that construct. Both ‘Influence of Others’ and ‘Sources of Quality Health Information’ had two vignettes, while ‘Self-efficacy, Resilience and Self-management’ and ‘Citizenship and Communication’ had three vignettes each. Since the items in the knowledge construct covered all the six cognitive processes according to Bloom’s taxonomy, no vignettes were associated with this construct.

DISCUSSION

This article presents the process and findings related to the qualitative methods undertaken to develop the vignettes and items in the AHLQ, measuring the health literacy of Irish adolescents aged 12–18 years old. Based on the constructs underlying the adolescents’ definition of healthy living, the emergent questionnaire items and vignettes are context relevant and thus could be useful for identifying the health literacy needs of Irish adolescents.

Findings from studies that have applied co-design approaches with adolescents show that these methods have the potential of maximizing the success of health literacy measurement and interventions (Smith et al., 2022). For example, Goss et al. (Goss et al., 2021) applied co-design approaches to develop an interactive health literacy intervention for socially disadvantaged adolescents in Ireland. Liu et al. (2014) engaged children and adolescents in the development of Taiwan’s Child Health Literacy Test for basic screening among children. The use of participatory methodology in the present study positioned the adolescents as the informing agents on their definition of healthy living, and context thereby ensuring that they were able to make fundamental contributions towards the conceptualization and development of the vignettes and questionnaire items. More so, this approach of considering the local emic perspectives of the target population is encouraged to avert possible epistemic injustice that may arise (Fricker, 2007; Bhakuni and Abimbola, 2021).

The adolescents in this study described healthy living as being multidimensional in nature, encompassing physical well-being, mental health, healthy eating and prioritizing rest, a perspective that finds support in literature. Similarly, other qualitative inquiries into how adolescents define health report that adolescents view health as a holistic concept relating to mental health, physical health and social well-being (O’Higgins et al., 2010). This similarity in the definition of health and or healthy living may be advantageous in harmonizing and developing health resources for adolescents in different contexts. From this standpoint, basing the development of the AHLQ and vignettes on constructs underlying the adolescents’ definition of healthy living is judicious, as the concept of health literacy is also recognized as a multidimensional concept that considers the social, cultural knowledge practices and contexts (Osborne et al., 2022).

The centrality of mental health in the adolescents’ definition of healthy living reflects its importance to the adolescents. In Ireland, adolescents attending lower secondary school learn about and focus on different aspects of health and well-being, as part of the Wellbeing curriculum that was introduced in 2017 (Department of Health Ireland et al., 2013; National Council for Curriculum and Assessment, 2017). Such national-level investment in initiatives and policy-level actions prioritizing mental health could have contributed toward shaping the adolescents’ perception of how central mental health is to healthy living.

The emergent constructs that were used to inform the development of the vignettes and questionnaire items are concepts that have been associated with health literacy in literature. Knowledge is one of the most widely described conceptual aspects of health literacy. For example, in their integrated model of health literacy, Sorensen et al. (Sørensen et al., 2012) position knowledge as a result of the process that enables them to navigate the domains of the health continuum. Within the context of adolescent health literacy, knowledge is viewed as one of the related dimensions that enable adolescents to competently interact with and use health information and derive at health-promoting actions (Bröder et al., 2017).

Adolescents today have access to health information from a variety of sources. In this study, the emergent construct of sources of quality health information may imply that the adolescents are also interested in how trustworthy the sources from which they get health information are. This resonates with the growing interest in understanding which sources adolescents trust for health information and what shapes this trust (Freeman et al., 2022).

Facilitators and barriers at individual-, community- or society-level influence how adolescents navigate health systems and use health information. For example, at individual level, having adequate health literacy skills may help adolescents overcome the barriers in accessing and utilizing available health information (Bröder et al., 2017). Beyond individual characteristics, the influence of others on adolescent health literacy has been widely documented. For example, parental health literacy and peer influence have been shown to influence how adolescents use the health information available to them to make health decisions (Manganello, 2008).

Cognitive attributes play a significant role in the health literacy of individuals; the beliefs that individuals have about how they engage with and use health information in health actions have been shown to determine their health outcomes (Liu et al., 2020). In the context of health, self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to perform health behaviors (Bandura, 1977). Evidence indicates that self-efficacy is one of the key determinants of health literacy, determining what health information individuals seek out (Gasser et al., 2012); how they perceive it (Liu et al., 2020); appraise (Binay and Yiğit, 2016); and use health information and sustain health behaviors (Ayres and Pontes, 2018). An individual’s ability to overcome and cope effectively in the face of hardship and challenges or to adjust and thrive in the face of a stressful environment refers to their resilience (Tugade et al., 2004). According to Bradley-Klug et al. (2017), the constructs of health literacy and resilience complement one another, especially in the management of illness. In non-clinical populations, resilience research focuses on the strengths and assets within communities and individuals that may buffer young people against negative health behaviors, poor dietary choices, among others (Rink and Tricker, 2005). The use of self-management strategies has been shown to be effective in the management of chronic conditions in adolescent samples. Adolescents equipped with self-management skills like realistic goal setting and planning have been shown to have better outcomes in weight treatment interventions (Thomason et al., 2016). Evidence also suggests that there is a link between self-management and health literacy; individuals with low levels of health literacy have been shown to have limited or apply self-management skills (Gazmararian et al., 2003). In their work defining health literacy as a learning outcome in schools, Paakkari and Paakkari (2012) defined citizenship as one of the core dimensions of health literacy. From this perspective, individuals consider health matters ‘through the lens of others’ and, of the collective, moving towards collective change that benefits others. To achieve this, it is imperative that individuals are able to communicate effectively and bring to light the facilitators and/or barriers to health literacy of communities and populations.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study contributes to the growing efforts to engage adolescents in the development of novel health literacy measurement instruments that capture their health literacy needs across the functional, interactive and critical dimensions.

A limitation of the study is the possibility that the adolescents who participated in the co-design workshops may have been disposed to the idea of healthy living by virtue of being members of the YAP. It is likely that they may be more familiar with the determinants of health and health literacy than the ‘average’ Irish adolescent.

Owing to the restrictions imposed during the Covid-19 pandemic, a fewer than anticipated number of adolescents actively participated in the qualitative development of the health literacy questionnaire, especially during the co-design workshops.

Recommendations for future research

Future efforts to improve the questionnaire and vignettes could benefit from including more adolescents in the initial co-design phases. Consideration to include adolescents who are not exclusively part of the YAP may be useful in getting more varied perspectives.

As shown, mental health is a priority for adolescent health and is intrinsically linked to other constructs of health, including physical health and healthy eating. From this standpoint, health literacy research and efforts could stand to benefit from incorporating competencies related to mental health in both the measurement and design of health literacy interventions for adolescents.

CONCLUSION

Applying co-design methodology with intended users of newly developed health literacy instruments provides an opportunity to develop context-specific and relevant instruments, as their unique and local emic perspectives are incorporated in the conceptual development of the instruments. Following additional psychometric validation, the AHLQ and vignettes developed have the potential to be adopted and used in health literacy research to provide useful data for policy-level actors and health promotion efforts targeting adolescents.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Irish Heart Foundation, research account number [R19539].

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Jennifer Kavanagh Joint first authors.