-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Guan-Soon Khoo, Jeeyun Oh, Soya Nah, Staying-at-Home with Tragedy: Self-expansion Through Narratives Promotes Positive Coping with Identity Threat, Human Communication Research, Volume 47, Issue 3, July 2021, Pages 309–334, https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqab005

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic created a historic opportunity to study the link between identity threat and individuals’ temporary expansion of the boundaries of the self (TEBOTS) through stories. Concurrently, the relationship between eudaimonic entertainment processes and self-expansion, particularly feeling moved and self-awareness, was examined. A quasi-experiment was conducted with an online sample (N = 172) that was randomly assigned to watch either a tragic drama or comedy. Results showed that key TEBOTS predictions were largely confirmed for boundary expansion and the outcomes of narrative engagement and entertainment gratifications. Although identity threat was negatively associated with positive coping with the pandemic, this relationship turned positive when mediated by boundary expansion. Further, exposure to tragedy raised feelings of “being moved,” which, in turn, was linked to self-perceptual depth and expanded boundaries of the self downstream. The present findings suggest that self-expansion through story consumption could benefit viewers’ positive reframing of challenging life experiences.

The early spread of COVID-19 in the United States went hand-in-hand with a sharp rise in media entertainment use. In mid-March 2020, when U.S. cities and states started to issue stay-at-home orders (Mervosh, Lu, & Swales, 2020), media entertainment use soared (Friedman, 2020). This heightened appeal of entertainment may have been instigated by the unexpected and often disruptive changes to people’s daily lives as a result of the pandemic. For example, despite public support for COVID-19 restrictions by a majority of Americans (68%; Daniller, 2020), some citizens have also defied precautionary local mandates, including gathering in large numbers (Ojeda, 2020). One explanation for this sensitivity to change is individuals’ perceived threat to their sense of self (Murtagh, Gatersleben, & Uzzell, 2012), which, in turn, has implications for their day-to-day behavior, including media entertainment use. A recently hypothesized entertainment model proposes that story engagement has the capacity to temporarily expand the boundaries of the self (TEBOTS: Slater, Johnson, Cohen, Comello, & Ewoldsen, 2014). The TEBOTS model is premised on the idea that the self-concept requires maintenance, and being swept away in a story provides relief from this constant psychological upkeep. Thus, when an individual’s identity is threatened during a collective response to a pandemic, narrative entertainment could offer a respite from the work of maintaining the self, which, in turn, may promote coping with the source of the threat.

The pandemic offers a unique opportunity to study our age-old fascination with stories, specifically when our identities come under threat. As the pandemic ruffles personal experiences, such as creating tensions in close relationships, and impinges on our values, such as limiting church gatherings, we may seek ways to temporarily alleviate the defense of our personal and social identities, including immersing ourselves in stories (Slater et al., 2014). Previous TEBOTS research that examined its main premise has focused on the strength model of self-control (Johnson, Ewoldsen, & Slater, 2015) and self-affirmation as identity protection (Johnson, Slater, Silver, & Ewoldsen, 2016), but identity threat at the personal and social levels has yet to be studied in this theoretical context. Drawing from theories of self-identity (Breakwell, 1986) and social identity (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), the current study expands on Slater et al.’s (2014) initial theorizing and tests a new measurement of identity threat in the TEBOTS context. In short, the present research fills a gap in the TEBOTS model by examining the unprecedented identity threats from the COVID-19 pandemic that may intensify our attraction to stories.

The current study also extends the implication of the TEBOTS model by bridging it with contemporary entertainment theory. Scholars have suggested that stories that portray human drama and feature life lessons tend to appeal to our meaning-seeking rather than pleasure-seeking motives (Bartsch & Oliver, 2017). The appeal of somber narratives rests on our motivation to seek out eudaimonic or meaningful experiences that could move us to contemplate life meanings (Oliver, 2008; Oliver & Bartsch, 2010). Eudaimonic entertainment responses are often described as mixed affective states, blending positive and negative affect, that are accompanied by reflection, which, in turn, may promote insight-gaining and personal growth. Although the early work on the TEBOTS model describes boundary expansion as a brief journey outside of the self (Slater et al., 2014), no TEBOTS study to date has assessed the capacity of “eudaimonic narratives” to expand the self inwards. Thus, the present research provides a first attempt to study the effects of eudaimonic entertainment responses on self-expansion.

Taken together, the present study advances the theorizing of the TEBOTS model in the area of identity threat and eudaimonic entertainment. Drawing from theories of personal and social identity, the present study will attempt to replicate central TEBOTS predictions by operationalizing identity threat in a pandemic with a new scale and examining its relationship with key outcomes, including story engagement and gratifications. Further, the potential benefits of boundary expansion will be tested as a mediator of the effect of identity threat on positive meaning-making in a pandemic. Finally, drawing from the eudaimonic entertainment framework, tragic drama (vs. light comedy) will be examined in an experiment to understand its capacity to indirectly increase self-expansion through feeling moved and reflective self-awareness.

The TEBOTS model

The temporary expansion of the boundaries of the self (TEBOTS; Slater et al., 2014) is a proposed explanation for our basic desire for narratives. These story engagement motives are based on the three underlying human motivations outlined in self-determination theory (Johnson et al., 2015; Slater et al., 2014): autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 1990). Slater et al. (2014) argue that these elements of intrinsic human motivation cannot be completely achieved “within the confines of the personal and social self” (p. 446) which is where the appeal of stories come into play. First, stories, or devices that allow us to mentally simulate different, alternative worlds (Oatley, 2002), can satisfy autonomy needs by allowing us to travel across various times, places, and social situations without the limitations of real-world realities (Slater et al., 2014). Further, the narrative processes associated with story worlds can fulfill our need for competence or agency through vicarious experiences with story characters and meet our need for relatedness through the simulated social relationships and imagined characters themselves (Slater et al., 2014). In sum, our experiences with stories allow us to venture beyond our self-concept to contribute to our fundamental strivings to achieve intrinsic needs as self-determined individuals.

Central to the TEBOTS model is the relationship between our subjective experience of self and the universal appeal of stories (Slater et al., 2014). This model explains the human motivation to engage with stories by positing the core assumption that we have an ongoing need to develop, sustain, and enrich our identities, self-concept, and self-presentation (Slater et al., 2014). However, this constant, sometimes effortful work takes a psychological toll, which drives us to find ways to provide relief from the toil, including story engagement (Slater et al., 2014). For example, if a person experiences challenges to their sense of self, they would show greater interest in watching a movie, given the chance, or become more engaged when reading a novel because the narrative experience eases the perceived threat to their sense of who they are. Further, as the constructed self is inherently constraining, narrative engagement could also provide opportunities for the individual to wander beyond the limits of current possibilities (Slater et al., 2014). In short, story engagement allows a temporary expansion of the confines of the self by providing momentary relief from its maintenance demands and brief opportunities to explore alternative worlds beyond the present self.

Identity threat in a pandemic and TEBOTS processes

The subjective self is a complex object of study that requires multiple approaches. Two previous TEBOTS studies have tested and confirmed its main predictions by focusing on the limited resources of self-regulation (Johnson et al., 2015) and encouraging a positive self-concept via self-affirmations (Johnson et al., 2016). A third approach to the subjective self in the TEBOTS context is to examine threats to personal and social identity that occur in the course of life experience (Slater et al., 2014). This approach can be understood through Identity Process Theory (Breakwell, 1986; Murtagh et al., 2012), which explains that identity is shaped by life experiences and reflections on those experiences (content) and the valence associated with those memories (value). Slater et al. (2014) speculated that personal or self-identity threat may be the result of personal events, including the decline or termination of a close relationship, physical incapacitation, or difficulties or distresses at school or work, whereas social identity threat may involve perceived risks or dangers to the values that are closely linked to the self-concept, such as ideology, religion, and national identity. Thus, the present approach offers an opportunity to examine TEBOTS processes that arise from life event-based identity threats.

The COVID-19 pandemic in the United States and its related public health restrictions have raised the potential for identity threat by creating disruptions in various aspects of people’s lives, ranging from work and personal activities to political beliefs. Previous research on Identity Process Theory (Breakwell, 1986) explains that self-identity threat is “an attack or potential attack on one or more of self-esteem, self-efficacy, continuity, or distinctiveness” (Murtagh et al., 2012, p. 319). Consequently, personal experiences that are related to the pandemic will affect one’s perceived self-threat. For example, as the pandemic limits the physical mobility of an avid jogger or the livelihood of a real estate agent, their sense of self-continuity would likely be disrupted, which may raise personal identity threat. On the other hand, social identity theory explains that aside from self-identity strivings, people also have a need for group membership; unmet group affiliation needs can threaten social identity (Scheepers & Ellemers, 2005; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). For example, conservative political partisans in the United States have been relatively less supportive of mandates on protective face mask use (Pew Research, 2020), presumably as a coping response to social identity threat. Taken together, the public response to a pandemic could increase the demands on the self by raising personal and social identity threat.

The TEBOTS model explains that the demands of maintaining our personal and social identity are momentarily lifted through self-expansion (Slater et al., 2014). Although a previous experiment did not find a direct effect of self-demands on boundary expansion using a self-affirmation task, the identity threat from actual life experiences should create a relatively stronger effect. In contrast to the previously documented small effects of self-affirmation (Epton, Harris, Kane, van Koningsbruggen, & Sheeran, 2015), pandemic-induced demands on the self are likely to produce a more robust association with boundary expansion. Further, prior research has shown that a greater challenge to the self-concept promotes higher levels of narrative engagement (Johnson et al., 2015, 2016). The two basic types of story engagement are transportation (Green & Brock, 2000), or the audience’s psychological shift into the story world, and character identification (Cohen, 2001), or the empathic link between audience and story character. Previous studies have found a direct link between self-demands and transportation, but not with identification (Johnson et al., 2015, 2016). Thus, based on the current state of TEBOTS research, identity threat is expected to be positively associated with boundary expansion and narrative transportation.

Slater et al. (2014) argued that the relief from the confines of identity may be “inherently gratifying” (p. 445). In the contemporary, two-factor model of entertainment (Oliver & Raney, 2011; Vorderer & Reinecke, 2015), the two central gratifications of interest are hedonic and eudaimonic satisfaction, which are often examined, respectively, as the pleasure-focused fun enjoyment and the deeper, more reflective set of gratifications called appreciation (Oliver & Bartsch, 2010) or eudaimonic entertainment experiences (Wirth, Hofer, & Schramm, 2012). Although the TEBOTS model generally predicts that threats to the subjective self are linked to story satisfaction, recent findings are less clear-cut. For example, Johnson et al. (2015) confirmed the link between self-depletion and several indicators of narrative satisfaction (intrinsic enjoyment, appreciation, and suspense), except for fun enjoyment; a similar null finding was also reported for hedonic enjoyment in a subsequent study (Johnson et al., 2016). Further, Johnson et al. (2016) reported that only readers with a high level of search for meaning in life, an individual difference that is linked to eudaimonic entertainment preferences (Hofer, 2013; Oliver & Raney, 2011), showed a positive link between self-threat and boundary expansion. These high meaning-seekers are likely paying greater attention to the eudaimonic story elements. In the current context, identity threat from an ongoing pandemic experience may have raised individuals’ degree of self-reflection and soul-searching that should also promote greater attention towards eudaimonic material, which is associated with contemplativeness. Consequently, the threat to identity may modify viewers’ appraisals of generic portrayals and promote greater appreciation (Oliver & Bartsch, 2010) than hedonic enjoyment. Taken together, identity threat in a pandemic should increase self-expansion, heighten narrative transportation, and raise appreciation. Thus, we predict the following:

H1: Identity threat from the COVID-19 pandemic will be positively associated with (a) boundary expansion, (b) transportation, and (c) appreciation, in the course of story exposure.

Boundary expansion is understood as an underlying mechanism in the TEBOTS model. In a set of mediation analyses, Johnson et al. (2016) hypothesized that boundary expansion would explain the impact of threat to the self-concept on gratifications (i.e., intrinsic enjoyment, fun enjoyment, appreciation, and suspense) and narrative engagement (i.e., transportation and identification), but their tests produced null results. However, in light of the existence of only one past attempt to examine the mediation effects of boundary expansion and the likelihood that identity threat from a pandemic creates greater variability in self-threat than a self-affirmation manipulation (used in Johnson et al., 2016), we propose a retest of the mediating effect of boundary expansion on story gratifications and engagement. For parsimony, only the fun enjoyment and appreciation dimensions of entertainment gratifications (Oliver & Bartsch, 2010) were included, not intrinsic enjoyment and suspense:

H2: Boundary expansion will mediate the effects of identity threat on (a) appreciation, (b) transportation, (c) fun enjoyment, and (d) character identification.

The causal ordering of boundary expansion followed by story engagement (i.e., transportation and identification) remains vulnerable to alternative explanations, including the possibility of a reverse order of causation. Although TEBOTS scholars have argued that temporary self-expansion precedes narrative engagement (Johnson et al., 2016; Slater et al., 2014), this specific causal ordering has not been empirically established. Johnson et al. (2016) conceptualized boundary expansion as an “on-line mental process” (p. 404), but constructed a self-report scale to measure the process retrospectively. Transportation and identification are also theorized and measured in similar fashion (Cohen, 2001; Green & Brock, 2000). On the other hand, the gratification variables of enjoyment and appreciation are commonly measured as overall or summary assessments of viewers’ entertainment experiences (Oliver & Bartsch, 2010). Consequently, these gratifications are considered outcomes of the processes of temporary self-expansion and story engagement. In light of these concerns, post hoc path analyses were conducted to compare the viability of the causal direction that was predicted in the TEBOTS model versus the reverse causal order where engagement precedes self-expansion.

As mentioned earlier, Johnson et al. (2016) reported that boundary expansion mediated the relationship between self-threat and story responses, but only when individual difference in searching for meaning-in-life was high. Meaning-in-life refers to the existential thoughts and feelings that human beings experience as we contemplate our sense of self and its relations with the wider world (Johnson et al., 2016; Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler, 2006). Although there are two dimensions of meaning-in-life (Steger et al., 2006), presence of and search for meaning, the latter is more immediately relevant to TEBOTS processes because story-based self-expansion may momentarily fulfill an existing quest for meaning (Johnson et al., 2016). Thus, in the vein of replicating past findings in a new context of pandemic-induced identity threat, the following set of moderated-mediation hypotheses are proposed:

H3: Search for meaning-in-life will moderate the mediating effect of identity threat, through boundary expansion, on (a) appreciation, (b) transportation, (c) fun enjoyment, and (d) character identification, such that higher search for meaning will produce positive indirect effects whereas lower search for meaning will not.

Coping with identity threat through boundary expansion

Although TEBOTS processes are not expected to fully resolve the identity threat that the individual faces, they should provide some relief from self-threat. Nevertheless, it remains an open question whether the experience of boundary expansion through story engagement could inspire positive coping with identity threat or “relief of self-related anxieties and tensions” (Slater et al., p. 448). Experiencing stories during a pandemic may promote boundary expansion processes that provide a reprieve from the pressures of pandemic-induced identity defense. Consequently, the typically negative link between identity threat and favorable perceptions of the pandemic may be reversed when this relationship is mediated by boundary expansion, such that greater identity threat leads to greater relief from self-demands via story engagement, which, in turn, encourages a more positive outlook on the pandemic. Previous research on responses to the aftermath of the attacks of 9/11 has examined the concept of “finding positive meaning” in the context of coping with negative emotions in a crisis (Fredrickson, Tugade, Waugh, & Larkin, 2003). Similarly, recent communication models of resilience have noted the value of reframing difficult life events (Buzzanell, 2010) and meaning-making in the face of adversity (Walsh, 2016). Applied to the present context, the temporary relief from self-demands that self-expansion provides may allow individuals to reappraise the impact of the pandemic and promote positive meaning-making related to pandemic threats. Thus, a positive indirect effect may occur between identity threat and finding positive meaning when this relationship is mediated by boundary expansion. In light of the lack of a theoretical link between boundary expansion and positive coping, we propose the following research question:

RQ1: Does boundary expansion mediate the effect of identity threat on finding positive meaning in a pandemic?

Eudaimonic responses and boundary expansion

Recent advances in entertainment theory on eudaimonic experiences may contribute to the TEBOTS model. The concept of eudaimonia or “happiness as living well” (Ryan, Huta, & Deci, 2006, p. 143) has been used in entertainment psychology to study the “paradoxical” appeal of somber portrayals of human struggle that the dominant, hedonic approach cannot fully explain (e.g., Oliver, 2008). Earlier research on eudaimonic entertainment (Oliver, 2008) drew on theories of eudaimonic well-being and self-determination (e.g., Ryan et al., 2006) to explain that our occasional attraction to somber material, such as sad drama, is motivated by a desire to have meaningful experiences and potentially gain insights that allow us to grow as persons. Eudaimonic portrayals tend to focus on the human condition and life meaning (Bartsch & Oliver, 2017) and are associated with the feeling of “being moved,” a “socially oriented affective state” (Bartsch, Kalch, & Oliver, 2014, p. 128). Being moved is the affective component of eudaimonic entertainment experiences that not only includes negative emotions, but is often characterized by “feelings of mixed affective valence, including tender, empathetic feelings, or poignancy” (Bartsch & Schneider, 2014, p. 377); feeling moved is related to but distinct from the blend of positive and negative affect known as “mixed affect” because the latter emphasizes the role of positivity in reframing painful or negative portrayals in a more reassuring manner (Bartsch et al., 2014). Previous TEBOTS research has examined story valence (Johnson et al., 2015, 2016) and speculated that genre may affect self-expansion (Slater et al., 2014), but the connection between self-expansion and emotionally moving narrative experiences has not been explored. Stories that are deeply moving may have a stronger impact on self-expansion than those that appeal to pleasure because of the human insights that they offer.

The key to understanding the link between eudaimonic entertainment experiences and self-expansion may rest on the emotion processing of the story experience. The feeling of being moved has a component of negative valence that motivates elaboration (Bartsch & Schneider, 2014). Self-focused elaboration may create self-awareness. Drawing from literary research, a study on tragic drama and contemplation argued that self-perceptual depth (Khoo, 2016), a form of self-awareness that resembles reflective private self-consciousness (Trapnell & Campbell, 1999), can be provoked by reflecting on somber films. Kuiken, Miall, and Sikora (2004) explain that reading literary fiction can arouse deep emotional responses that resemble “mourning,” especially when the reader’s personal life briefly merges with elements of the story, such as characters or plot events. Self-perceptual depth refers to a self-awareness of past life experiences that have been set aside or ignored by the individual (Khoo, 2016; Kuiken et al., 2004). Khoo (2016) argued that the self-focused attention that arises from reflecting on tragic drama could encourage self-knowledge, which is associated with self-acceptance, a form of personal growth. Applied to the present study, exposure to a tragedy should raise the feeling of being moved, which, in turn, generate elaboration that may promote insights if the elaboration creates a self-awareness of past life events, including negative ones. Consequently, the self-awareness and insights from the emotionally moving story experience could produce an expansion of the confined self in an inward direction. Based on this untested integration of the eudaimonic framework and tragedy research into the TEBOTS model, we inquire the following:

RQ2: Does tragic drama indirectly raise boundary expansion through the underlying processes of feeling moved followed by self-perceptual depth?

Method

Overview, sample, and study design

Participants were recruited online through the Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) service. A study called “Media Entertainment Study” was posted electronically from May 12th to 15th, 2020. Each participant received the U.S. $5.00 in compensation. Thirteen cases (n = 13) were removed right after data collection for inattentive responses, such as showing disregard for reading instructions and failing to respond to stimulus exposure checks. Prior to analysis, the data was checked again for participant attentiveness using five items that were embedded in the questionnaire including film quizzes and mini writing tasks. Each participant received one point for each attention “error,” and the final sample included participants who made one “error” or fewer, which resulted in the exclusion of nine cases (n = 9) from the data analysis. Overall, the final sample consisted of one hundred and seventy-two participants (N = 172), where 46.5% were female, 79.1% were White, and the average age was 39 years (SD = 11.52). The majority of the participants had attained some level of higher education with 61.6% reporting having at least a 4-year college degree. The median household income for the participants ranged from $50,000 to $59,990. For political ideology, 8.1% of the participants were very conservative, 23.8% were conservative, 24.4% were moderate, 27.9% were liberal, and 15.7% were very liberal.

An IRB-approved quasi-experiment was conducted in which identity threat was measured and film exposure was manipulated (tragic drama or control). Cell sizes are nearly evenly split between the tragedy group (n = 89) and comedy control condition (n = 83). Before film exposure, participants reported their general preferences for comedy (M = 5.50, SD = 1.40) and drama (M = 5.37, SD = 1.40) using a 7-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much). Since the drama contained storylines involving the loss of a child, participants were also asked to indicate whether they have children and 54.1% of participants answered yes. Participants spent an average of 42 minutes (SD = 20.03) to complete the study. There were no statistically significant differences between the two film conditions on age, sex, ideology, income, having children, comedy preference, and drama preference.

Stimulus materials

Scenes from Hollywood films were edited together to create shortened, 15-minute mini-movies. For each shortened movie, scenes were edited together with explanatory titles to create a storyline with a beginning, middle, and end. Two different films were used for each condition. For tragic drama, the films Mystic River (2003) and In the Bedroom (2001) were selected, whereas Wedding Crashers (2005) and Superbad (2007) were light comedies for the control group. Both drama storylines focus on a parent who loses a beloved teenage child to violence and commits revenge only to remain tormented; Mystic River centers on a male parent who has connections with organized crime, whereas In the Bedroom focuses on a suburban mom and dad. The comedies revolve around two male friends who seek out casual sex and friendship; Wedding Crashers depicts two young, working adults who find “true love” at the end, whereas Superbad, portrays two teenagers who strive to be popular in high school just before leaving for college.

The tragic films were pretested and used in a previous research on the benefits of tragedy (Khoo, 2016), whereas the two comedies were selected from an unpublished study. The use of two films in each condition helps to reduce concerns over the unique effects of a single film. The two films in each condition were collapsed for analysis. Regarding prior film exposure, 19.2% of participants reported that they had seen the movie in full before the study.

Procedures

Data collection was conducted using the Qualtrics software. First, participants were given an informed consent form and completed a prequestionnaire. Prior to watching the stimulus, participants were asked to use earphones and check their audio volume. Later, they were randomly placed into either the tragic drama or light comedy condition. Participants in the tragic drama condition watched either Mystic River (2003) or In the Bedroom (2001). On the other hand, participants in the light comedy condition were shown either Wedding Crashers (2005) or Superbad (2007). After film exposure, participants were asked to write down everything that went through their mind during and after the film and were asked to answer a poststimulus questionnaire. Lastly, they were asked to report their demographic information.

Measurements

Overview: Self-reported measures were used throughout the study. Participants rated items on 7-point scales from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), unless noted otherwise below. Cronbach’s alpha was used to inspect interitem reliabilities.

Identity threat during the pandemic: A 7-item measure was newly created from TEBOTS discussions in Slater et al. (2014) regarding personal (e.g., “The pandemic has negatively affected my close relationship(s)”) and social identity threat (e.g., “The pandemic has threatened my political beliefs (M = 3.16, SD = 1.37, α = 0.83)). The new scale was also checked for convergent validity with a 4-item measure from Murtagh et al. (2012) (M = 2.53, SD = 1.64, α = 0.91); a sample item includes “The pandemic undermines my sense of self-worth.” The correlation between the two measures was very strong, Pearson’s r = 0.83, p < .001.

Boundary expansion: This concept was measured using a 10-item scale from Johnson et al. (2016), on an 11-point scale (0 = not at all to 10 = very much). Participants were asked how much they experienced intrinsic needs-based self-expansion while watching the movie, such as “Relationships between people that are different from relationships in your life?,” “What it might be like to relate to others in ways different than you normally do yourself?,” and “Getting to know people you would never otherwise know?” (M = 5.44, SD = 2.22, α = 0.90).

Eudaimonic and hedonic entertainment gratifications: Appreciation and fun enjoyment were measured using the scales from Oliver and Bartsch (2010). More specifically, appreciation was measured with the subscales of (a) moving/thought-provoking and (b) lasting impression, each consisting of three items. Examples included “I found this movie to be very meaningful” for moving/thought-provoking, “This movie will stick with me for a long time” for lasting impression (M = 4.61, SD = 1.79, α = 0.93). Fun enjoyment, on the other hand, was measured with three items, such as “It was fun for me to watch this movie” (M = 5.03, SD = 1.64, α = 0.89).

Transportation: The 6-item short-form transportation scale by Appel, Gnambs, Richter, and Green (2015) was used, but some words were slightly modified such as the word “narrative” was changed to “movie.” Participants were asked to rate their movie-watching experiences with statements such as “I could picture myself in the scene of the events in the movie” and “I was mentally involved in the movie while watching it” on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much) (M = 5.03, SD = 1.40, α = 0.88).

Identification: A 6-item short scale of character identification from de Graaf, Hoeken, Sanders, and Beentjes’s (2012) was used. Participants indicated their level of agreement with the statements regarding the movie character, such as “In my imagination it was as if I was [character]” and “I put myself in [character’s] position” (M = 4.74, SD = 1.70, α = 0.93).

Finding positive meaning: The 5-item positive meaning scale from Fredrickson et al. (2003) was used. Participants were asked to indicate how they perceived the current pandemic with statements (e.g., “Something good may come out of dealing with the pandemic”) on a 4-point scale from 0 (definitely no) to 3 (definitely yes) (M = 2.12, SD = 0.75, α = 0.87). They were also given an additional fifth option (not applicable), which was scored as missing data.

Search for meaning in life: Five items from Steger et al. (2006) were employed; examples include: “I am looking for something that makes my life feel meaningful,” “I am seeking a purpose or mission for my life” (M = 3.93, SD = 1.85, α = 0.96).

Feeling moved: Three emotion words that have been found to correlate with reflective experiences in previous entertainment studies (e.g., Bartsch & Schneider, 2014) were used to measure being moved: “moved,” “tender,” and “poignant” (M = 3.04, SD = 1.60, α = 0.81).

Self-perceptual depth: Deep self-awareness was measured with three items from Sikora, Kuiken, and Miall (2010). Sample items include, “I began to understand my past differently” and “I began to understand some of my more negative feelings” (M = 3.03, SD = 1.73, α = 0.89).

Results

Preliminary analyses and manipulation check

Table 1 displays correlations between every study variable. All continuous variables in the analysis were also checked for normality and univariate outliers. Skewness ranged from −0.91 to 0.74, and no univariate outlier was found. Further, the current study compared tragic versus comedy films with an assumption that the stimuli would be equally involving and show a comparable level of story clarity. Two items (“The movie was engaging or involving”; “The overall story clarity was good”) on a 7-point Likert scale were used to check this assumption. Tragic drama and comedy stimuli were not significantly different in involvement, t (170) = 1.97, p = .05, and story clarity, t (170) = 0.09, p = .93, respectively. All four films were also compared on key variables; the movie differences were largely as expected (see Table 2).

| . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | 12 . | 13 . | 14 . | 15 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Identity threat | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Stimulus film | −0.04 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3. Boundary expansion | 0.35*** | 0.16* | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4. Appreciation | 0.27*** | 0.40*** | 0.52*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5. Enjoyment | 0.14 | −0.29*** | 0.32*** | 0.41*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 6. Transportation | 0.22** | 0.28*** | 0.56*** | 0.77*** | 0.42*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 7. Identification | 0.19* | 0.36*** | 0.56*** | 0.79*** | 0.27*** | 0.75*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 8. Finding positive meaning | −0.06 | −0.10 | 0.26** | 0.15* | 0.31*** | 0.20** | 0.20** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 9. Search for meaning in life | 0.39*** | −0.02 | 0.23** | 0.20* | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 10. Moved | 0.44*** | 0.25** | 0.40*** | 0.59*** | 0.18* | 0.48*** | 0.52*** | 0.16* | 0.27*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 11. Self-perceptual depth | 0.47*** | 0.16* | 0.51*** | 0.57*** | 0.21** | 0.52*** | 0.56*** | 0.17* | 0.33*** | 0.55*** | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| 12. Age | −0.02 | −0.12 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.10 | 0.06 | −0.19* | 0.05 | −0.09 | 1 | – | – | – |

| 13. Sex | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.14 | 0.02 | −0.10 | −0.07 | −0.18* | 0.03 | 1 | – | – |

| 14. Children | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.26** | 0.16* | 0.20** | 0.26** | 0.09 | −0.13 | 0.22** | 0.23** | 0.30** | 0.06 | 1 | – |

| 15. Drama pref. | 0.23** | 0.08 | 0.26*** | 0.19* | 0.11 | 0.18* | 0.22** | 0.19* | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.22** | 0.09 | 0.13 | 1 |

| . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | 12 . | 13 . | 14 . | 15 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Identity threat | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Stimulus film | −0.04 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3. Boundary expansion | 0.35*** | 0.16* | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4. Appreciation | 0.27*** | 0.40*** | 0.52*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5. Enjoyment | 0.14 | −0.29*** | 0.32*** | 0.41*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 6. Transportation | 0.22** | 0.28*** | 0.56*** | 0.77*** | 0.42*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 7. Identification | 0.19* | 0.36*** | 0.56*** | 0.79*** | 0.27*** | 0.75*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 8. Finding positive meaning | −0.06 | −0.10 | 0.26** | 0.15* | 0.31*** | 0.20** | 0.20** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 9. Search for meaning in life | 0.39*** | −0.02 | 0.23** | 0.20* | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 10. Moved | 0.44*** | 0.25** | 0.40*** | 0.59*** | 0.18* | 0.48*** | 0.52*** | 0.16* | 0.27*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 11. Self-perceptual depth | 0.47*** | 0.16* | 0.51*** | 0.57*** | 0.21** | 0.52*** | 0.56*** | 0.17* | 0.33*** | 0.55*** | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| 12. Age | −0.02 | −0.12 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.10 | 0.06 | −0.19* | 0.05 | −0.09 | 1 | – | – | – |

| 13. Sex | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.14 | 0.02 | −0.10 | −0.07 | −0.18* | 0.03 | 1 | – | – |

| 14. Children | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.26** | 0.16* | 0.20** | 0.26** | 0.09 | −0.13 | 0.22** | 0.23** | 0.30** | 0.06 | 1 | – |

| 15. Drama pref. | 0.23** | 0.08 | 0.26*** | 0.19* | 0.11 | 0.18* | 0.22** | 0.19* | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.22** | 0.09 | 0.13 | 1 |

Notes: Sex is coded as male = 1 and female = 2; stimulus film is coded as tragedy = 1 and comedy = 0.

p < .05*, p < 01**, p < .001***

| . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | 12 . | 13 . | 14 . | 15 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Identity threat | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Stimulus film | −0.04 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3. Boundary expansion | 0.35*** | 0.16* | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4. Appreciation | 0.27*** | 0.40*** | 0.52*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5. Enjoyment | 0.14 | −0.29*** | 0.32*** | 0.41*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 6. Transportation | 0.22** | 0.28*** | 0.56*** | 0.77*** | 0.42*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 7. Identification | 0.19* | 0.36*** | 0.56*** | 0.79*** | 0.27*** | 0.75*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 8. Finding positive meaning | −0.06 | −0.10 | 0.26** | 0.15* | 0.31*** | 0.20** | 0.20** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 9. Search for meaning in life | 0.39*** | −0.02 | 0.23** | 0.20* | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 10. Moved | 0.44*** | 0.25** | 0.40*** | 0.59*** | 0.18* | 0.48*** | 0.52*** | 0.16* | 0.27*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 11. Self-perceptual depth | 0.47*** | 0.16* | 0.51*** | 0.57*** | 0.21** | 0.52*** | 0.56*** | 0.17* | 0.33*** | 0.55*** | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| 12. Age | −0.02 | −0.12 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.10 | 0.06 | −0.19* | 0.05 | −0.09 | 1 | – | – | – |

| 13. Sex | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.14 | 0.02 | −0.10 | −0.07 | −0.18* | 0.03 | 1 | – | – |

| 14. Children | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.26** | 0.16* | 0.20** | 0.26** | 0.09 | −0.13 | 0.22** | 0.23** | 0.30** | 0.06 | 1 | – |

| 15. Drama pref. | 0.23** | 0.08 | 0.26*** | 0.19* | 0.11 | 0.18* | 0.22** | 0.19* | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.22** | 0.09 | 0.13 | 1 |

| . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | 12 . | 13 . | 14 . | 15 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Identity threat | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Stimulus film | −0.04 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3. Boundary expansion | 0.35*** | 0.16* | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4. Appreciation | 0.27*** | 0.40*** | 0.52*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5. Enjoyment | 0.14 | −0.29*** | 0.32*** | 0.41*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 6. Transportation | 0.22** | 0.28*** | 0.56*** | 0.77*** | 0.42*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 7. Identification | 0.19* | 0.36*** | 0.56*** | 0.79*** | 0.27*** | 0.75*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 8. Finding positive meaning | −0.06 | −0.10 | 0.26** | 0.15* | 0.31*** | 0.20** | 0.20** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 9. Search for meaning in life | 0.39*** | −0.02 | 0.23** | 0.20* | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 10. Moved | 0.44*** | 0.25** | 0.40*** | 0.59*** | 0.18* | 0.48*** | 0.52*** | 0.16* | 0.27*** | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 11. Self-perceptual depth | 0.47*** | 0.16* | 0.51*** | 0.57*** | 0.21** | 0.52*** | 0.56*** | 0.17* | 0.33*** | 0.55*** | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| 12. Age | −0.02 | −0.12 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.10 | 0.06 | −0.19* | 0.05 | −0.09 | 1 | – | – | – |

| 13. Sex | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.14 | 0.02 | −0.10 | −0.07 | −0.18* | 0.03 | 1 | – | – |

| 14. Children | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.26** | 0.16* | 0.20** | 0.26** | 0.09 | −0.13 | 0.22** | 0.23** | 0.30** | 0.06 | 1 | – |

| 15. Drama pref. | 0.23** | 0.08 | 0.26*** | 0.19* | 0.11 | 0.18* | 0.22** | 0.19* | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.22** | 0.09 | 0.13 | 1 |

Notes: Sex is coded as male = 1 and female = 2; stimulus film is coded as tragedy = 1 and comedy = 0.

p < .05*, p < 01**, p < .001***

| Key variables . | MR . | IB . | WC . | SB . | ANOVA results . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 46) . | (n = 43) . | (n = 42) . | (n = 41) . | ||

| Boundary expansion | 5.90a | 5.64 | 5.70 | 4.45a | F(3, 168) = 3.87, p < .05 |

| (2.05) | (1.84) | (2.32) | (2.43) | ||

| Transportation | 5.36a | 5.45b | 4.74 | 4.52a,b | F(3, 168) = 4.83, p < .01 |

| (1.45) | (1.09) | (1.27) | (1.58) | ||

| Identification | 5.21a,b | 5.46c,d | 4.28a,c | 3.92b,d | F(3, 168) = 9.09, p < .001 |

| (1.12) | (1.32) | (1.85) | (1.97) | ||

| Enjoyment | 4.91 | 4.20a,b | 5.68a | 5.35b | F(3, 168) = 7.16, p < .001 |

| (1.62) | (1.47) | (1.42) | (1.72) | ||

| Appreciation as moving/ thought-provoking | 5.52a,b | 5.44c,d | 3.81a,c | 3.54b,d | F(3, 168) = 19.72, p < .001 |

| (1.37) | (1.22) | (1.87) | (1.68) | ||

| Appreciation as lasting impression | 4.96a | 4.87b | 4.30 | 3.80a,b | F(3, 168) = 4.07, p < .01 |

| (1.70) | (1.54) | (1.78) | (1.99) | ||

| Finding positive meaning | 2.18 | 1.91a | 2.40a | 1.98 | F(3, 168) = 3.88, p < .05 |

| (0.83) | (0.67) | (0.53) | (0.85) | ||

| Feeling moved | 3.65a | 3.19 | 2.90 | 2.33a | F(3, 168) = 5.55, p < .01 |

| (1.69) | (1.51) | (1.67) | (1.22) | ||

| Self-perceptual depth | 3.25 | 3.36 | 2.92 | 2.55 | F(3, 168) = 1.88, n.s. |

| (1.82) | (1.79) | (1.71) | (1.53) |

| Key variables . | MR . | IB . | WC . | SB . | ANOVA results . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 46) . | (n = 43) . | (n = 42) . | (n = 41) . | ||

| Boundary expansion | 5.90a | 5.64 | 5.70 | 4.45a | F(3, 168) = 3.87, p < .05 |

| (2.05) | (1.84) | (2.32) | (2.43) | ||

| Transportation | 5.36a | 5.45b | 4.74 | 4.52a,b | F(3, 168) = 4.83, p < .01 |

| (1.45) | (1.09) | (1.27) | (1.58) | ||

| Identification | 5.21a,b | 5.46c,d | 4.28a,c | 3.92b,d | F(3, 168) = 9.09, p < .001 |

| (1.12) | (1.32) | (1.85) | (1.97) | ||

| Enjoyment | 4.91 | 4.20a,b | 5.68a | 5.35b | F(3, 168) = 7.16, p < .001 |

| (1.62) | (1.47) | (1.42) | (1.72) | ||

| Appreciation as moving/ thought-provoking | 5.52a,b | 5.44c,d | 3.81a,c | 3.54b,d | F(3, 168) = 19.72, p < .001 |

| (1.37) | (1.22) | (1.87) | (1.68) | ||

| Appreciation as lasting impression | 4.96a | 4.87b | 4.30 | 3.80a,b | F(3, 168) = 4.07, p < .01 |

| (1.70) | (1.54) | (1.78) | (1.99) | ||

| Finding positive meaning | 2.18 | 1.91a | 2.40a | 1.98 | F(3, 168) = 3.88, p < .05 |

| (0.83) | (0.67) | (0.53) | (0.85) | ||

| Feeling moved | 3.65a | 3.19 | 2.90 | 2.33a | F(3, 168) = 5.55, p < .01 |

| (1.69) | (1.51) | (1.67) | (1.22) | ||

| Self-perceptual depth | 3.25 | 3.36 | 2.92 | 2.55 | F(3, 168) = 1.88, n.s. |

| (1.82) | (1.79) | (1.71) | (1.53) |

Notes: MR refers to Mystic River (2003), IB is In the Bedroom (2001), WC is Wedding Crashers (2005), SB is Superbad (2007). Standard deviations are in parenthesis. Bonferroni pairwise comparisons were used. Means in each row that share the same subscript differ at p < .05 or better.

| Key variables . | MR . | IB . | WC . | SB . | ANOVA results . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 46) . | (n = 43) . | (n = 42) . | (n = 41) . | ||

| Boundary expansion | 5.90a | 5.64 | 5.70 | 4.45a | F(3, 168) = 3.87, p < .05 |

| (2.05) | (1.84) | (2.32) | (2.43) | ||

| Transportation | 5.36a | 5.45b | 4.74 | 4.52a,b | F(3, 168) = 4.83, p < .01 |

| (1.45) | (1.09) | (1.27) | (1.58) | ||

| Identification | 5.21a,b | 5.46c,d | 4.28a,c | 3.92b,d | F(3, 168) = 9.09, p < .001 |

| (1.12) | (1.32) | (1.85) | (1.97) | ||

| Enjoyment | 4.91 | 4.20a,b | 5.68a | 5.35b | F(3, 168) = 7.16, p < .001 |

| (1.62) | (1.47) | (1.42) | (1.72) | ||

| Appreciation as moving/ thought-provoking | 5.52a,b | 5.44c,d | 3.81a,c | 3.54b,d | F(3, 168) = 19.72, p < .001 |

| (1.37) | (1.22) | (1.87) | (1.68) | ||

| Appreciation as lasting impression | 4.96a | 4.87b | 4.30 | 3.80a,b | F(3, 168) = 4.07, p < .01 |

| (1.70) | (1.54) | (1.78) | (1.99) | ||

| Finding positive meaning | 2.18 | 1.91a | 2.40a | 1.98 | F(3, 168) = 3.88, p < .05 |

| (0.83) | (0.67) | (0.53) | (0.85) | ||

| Feeling moved | 3.65a | 3.19 | 2.90 | 2.33a | F(3, 168) = 5.55, p < .01 |

| (1.69) | (1.51) | (1.67) | (1.22) | ||

| Self-perceptual depth | 3.25 | 3.36 | 2.92 | 2.55 | F(3, 168) = 1.88, n.s. |

| (1.82) | (1.79) | (1.71) | (1.53) |

| Key variables . | MR . | IB . | WC . | SB . | ANOVA results . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 46) . | (n = 43) . | (n = 42) . | (n = 41) . | ||

| Boundary expansion | 5.90a | 5.64 | 5.70 | 4.45a | F(3, 168) = 3.87, p < .05 |

| (2.05) | (1.84) | (2.32) | (2.43) | ||

| Transportation | 5.36a | 5.45b | 4.74 | 4.52a,b | F(3, 168) = 4.83, p < .01 |

| (1.45) | (1.09) | (1.27) | (1.58) | ||

| Identification | 5.21a,b | 5.46c,d | 4.28a,c | 3.92b,d | F(3, 168) = 9.09, p < .001 |

| (1.12) | (1.32) | (1.85) | (1.97) | ||

| Enjoyment | 4.91 | 4.20a,b | 5.68a | 5.35b | F(3, 168) = 7.16, p < .001 |

| (1.62) | (1.47) | (1.42) | (1.72) | ||

| Appreciation as moving/ thought-provoking | 5.52a,b | 5.44c,d | 3.81a,c | 3.54b,d | F(3, 168) = 19.72, p < .001 |

| (1.37) | (1.22) | (1.87) | (1.68) | ||

| Appreciation as lasting impression | 4.96a | 4.87b | 4.30 | 3.80a,b | F(3, 168) = 4.07, p < .01 |

| (1.70) | (1.54) | (1.78) | (1.99) | ||

| Finding positive meaning | 2.18 | 1.91a | 2.40a | 1.98 | F(3, 168) = 3.88, p < .05 |

| (0.83) | (0.67) | (0.53) | (0.85) | ||

| Feeling moved | 3.65a | 3.19 | 2.90 | 2.33a | F(3, 168) = 5.55, p < .01 |

| (1.69) | (1.51) | (1.67) | (1.22) | ||

| Self-perceptual depth | 3.25 | 3.36 | 2.92 | 2.55 | F(3, 168) = 1.88, n.s. |

| (1.82) | (1.79) | (1.71) | (1.53) |

Notes: MR refers to Mystic River (2003), IB is In the Bedroom (2001), WC is Wedding Crashers (2005), SB is Superbad (2007). Standard deviations are in parenthesis. Bonferroni pairwise comparisons were used. Means in each row that share the same subscript differ at p < .05 or better.

Following the recommendations of O’Keefe (2003), the measurement of feeling moved was used as the manipulation check for stimulus film as well as a mediator for exploring RQ2. As expected, tragedy (M = 3.43, SD = 1.61) was significantly more moving than comedy (M = 2.62, SD = 1.48), t (170) = 3.41, p < .001. Thus, the film manipulation was deemed effective.

Main analyses

H1: Three ordinary least squares hierarchical regression models were used to test H1a to H1c. All models shared the same predictors. Boundary expansion, transportation, and appreciation were regressed onto the same set of independent variables in the order listed below.

In all models, individual differences (age, sex, having children or not, and drama preference) were entered in Step 1, and stimulus film (tragedy vs. comedy) was entered in Step 2. Step 3 examined the effect of the key independent variable, identity threat (Table 3). As hypothesized, identity threat amid the pandemic significantly and positively predicted boundary expansion, transportation, and appreciation after controlling for individual differences and stimulus film. Individuals who felt greater threat to identity were more likely to experience boundary expansion, transportation, and appreciation. Thus, H1a, H1b, and H1c were supported.

Regression Models Testing the Effects of Identity Threat on Dependent Variables

| . | Boundary expansion . | Transportation . | Appreciation . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Individual difference | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) |

| Age | −0.03 (0.02)* | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.03 (0.01)** |

| Sex | −0.04 (0.33) | −0.16 (0.21) | −0.21 (0.24) |

| Children | 0.62 (0.34) | 0.62 (0.22)** | 0.99 (0.26)*** |

| Drama preference | 0.45 (0.12)*** | 0.20 (0.08)* | 0.25 (0.09)** |

| ΔR2 | 0.10** | 0.09** | 0.13*** |

| Step 2: Stimulus film | |||

| Age | −0.03 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) |

| Sex | −0.01 (0.33) | −0.13 (0.20) | −0.16 (0.23) |

| Children | 0.56 (0.34) | 0.54 (0.21)* | 0.84 (0.24)** |

| Drama preference | 0.43 (0.12)** | 0.17 (0.08)* | 0.20 (0.09)* |

| Stimulus film | 0.47 (0.33)** | 0.64 (0.21)** | 1.15 (0.23)*** |

| ΔR2 | 0.01 | 0.05** | 0.11*** |

| Step 3: Identity threat | |||

| Age | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) |

| Sex | 0.13 (0.31) | −0.08 (0.20) | −0.08 (0.23) |

| Children | 0.33 (0.33) | 0.45 (0.21)* | 0.72 (0.24)** |

| Drama preference | 0.31 (0.12)* | 0.12 (0.08) | 0.13 (0.09) |

| Stimulus film | 0.60 (0.32) | 0.69 (0.21)*** | 1.22 (0.23)*** |

| Identity threat | 0.49 (0.12)*** | 0.18 (0.08)* | 0.27 (0.09)** |

| ΔR2 | 0.08*** | 0.03* | 0.04** |

| Total R2 | 0.19*** | 0.17*** | 0.29*** |

| . | Boundary expansion . | Transportation . | Appreciation . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Individual difference | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) |

| Age | −0.03 (0.02)* | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.03 (0.01)** |

| Sex | −0.04 (0.33) | −0.16 (0.21) | −0.21 (0.24) |

| Children | 0.62 (0.34) | 0.62 (0.22)** | 0.99 (0.26)*** |

| Drama preference | 0.45 (0.12)*** | 0.20 (0.08)* | 0.25 (0.09)** |

| ΔR2 | 0.10** | 0.09** | 0.13*** |

| Step 2: Stimulus film | |||

| Age | −0.03 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) |

| Sex | −0.01 (0.33) | −0.13 (0.20) | −0.16 (0.23) |

| Children | 0.56 (0.34) | 0.54 (0.21)* | 0.84 (0.24)** |

| Drama preference | 0.43 (0.12)** | 0.17 (0.08)* | 0.20 (0.09)* |

| Stimulus film | 0.47 (0.33)** | 0.64 (0.21)** | 1.15 (0.23)*** |

| ΔR2 | 0.01 | 0.05** | 0.11*** |

| Step 3: Identity threat | |||

| Age | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) |

| Sex | 0.13 (0.31) | −0.08 (0.20) | −0.08 (0.23) |

| Children | 0.33 (0.33) | 0.45 (0.21)* | 0.72 (0.24)** |

| Drama preference | 0.31 (0.12)* | 0.12 (0.08) | 0.13 (0.09) |

| Stimulus film | 0.60 (0.32) | 0.69 (0.21)*** | 1.22 (0.23)*** |

| Identity threat | 0.49 (0.12)*** | 0.18 (0.08)* | 0.27 (0.09)** |

| ΔR2 | 0.08*** | 0.03* | 0.04** |

| Total R2 | 0.19*** | 0.17*** | 0.29*** |

Notes: Coefficients after controlling for the previous step are bolded; sex is coded as male = 1 and female = 2; stimulus film is coded as tragedy = 1 and comedy = 0.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Regression Models Testing the Effects of Identity Threat on Dependent Variables

| . | Boundary expansion . | Transportation . | Appreciation . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Individual difference | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) |

| Age | −0.03 (0.02)* | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.03 (0.01)** |

| Sex | −0.04 (0.33) | −0.16 (0.21) | −0.21 (0.24) |

| Children | 0.62 (0.34) | 0.62 (0.22)** | 0.99 (0.26)*** |

| Drama preference | 0.45 (0.12)*** | 0.20 (0.08)* | 0.25 (0.09)** |

| ΔR2 | 0.10** | 0.09** | 0.13*** |

| Step 2: Stimulus film | |||

| Age | −0.03 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) |

| Sex | −0.01 (0.33) | −0.13 (0.20) | −0.16 (0.23) |

| Children | 0.56 (0.34) | 0.54 (0.21)* | 0.84 (0.24)** |

| Drama preference | 0.43 (0.12)** | 0.17 (0.08)* | 0.20 (0.09)* |

| Stimulus film | 0.47 (0.33)** | 0.64 (0.21)** | 1.15 (0.23)*** |

| ΔR2 | 0.01 | 0.05** | 0.11*** |

| Step 3: Identity threat | |||

| Age | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) |

| Sex | 0.13 (0.31) | −0.08 (0.20) | −0.08 (0.23) |

| Children | 0.33 (0.33) | 0.45 (0.21)* | 0.72 (0.24)** |

| Drama preference | 0.31 (0.12)* | 0.12 (0.08) | 0.13 (0.09) |

| Stimulus film | 0.60 (0.32) | 0.69 (0.21)*** | 1.22 (0.23)*** |

| Identity threat | 0.49 (0.12)*** | 0.18 (0.08)* | 0.27 (0.09)** |

| ΔR2 | 0.08*** | 0.03* | 0.04** |

| Total R2 | 0.19*** | 0.17*** | 0.29*** |

| . | Boundary expansion . | Transportation . | Appreciation . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Individual difference | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) |

| Age | −0.03 (0.02)* | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.03 (0.01)** |

| Sex | −0.04 (0.33) | −0.16 (0.21) | −0.21 (0.24) |

| Children | 0.62 (0.34) | 0.62 (0.22)** | 0.99 (0.26)*** |

| Drama preference | 0.45 (0.12)*** | 0.20 (0.08)* | 0.25 (0.09)** |

| ΔR2 | 0.10** | 0.09** | 0.13*** |

| Step 2: Stimulus film | |||

| Age | −0.03 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) |

| Sex | −0.01 (0.33) | −0.13 (0.20) | −0.16 (0.23) |

| Children | 0.56 (0.34) | 0.54 (0.21)* | 0.84 (0.24)** |

| Drama preference | 0.43 (0.12)** | 0.17 (0.08)* | 0.20 (0.09)* |

| Stimulus film | 0.47 (0.33)** | 0.64 (0.21)** | 1.15 (0.23)*** |

| ΔR2 | 0.01 | 0.05** | 0.11*** |

| Step 3: Identity threat | |||

| Age | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) |

| Sex | 0.13 (0.31) | −0.08 (0.20) | −0.08 (0.23) |

| Children | 0.33 (0.33) | 0.45 (0.21)* | 0.72 (0.24)** |

| Drama preference | 0.31 (0.12)* | 0.12 (0.08) | 0.13 (0.09) |

| Stimulus film | 0.60 (0.32) | 0.69 (0.21)*** | 1.22 (0.23)*** |

| Identity threat | 0.49 (0.12)*** | 0.18 (0.08)* | 0.27 (0.09)** |

| ΔR2 | 0.08*** | 0.03* | 0.04** |

| Total R2 | 0.19*** | 0.17*** | 0.29*** |

Notes: Coefficients after controlling for the previous step are bolded; sex is coded as male = 1 and female = 2; stimulus film is coded as tragedy = 1 and comedy = 0.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

H2: Model 4 of the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2012) was used to examine H2. Model 4 uses a standard OLS regression-based approach to test the effect of predictors and a bootstrapped method to test mediation. Identity threat was entered as the independent variable, and boundary expansion as the mediator. Control variables were stimulus film (1 = tragedy, 0 = comedy), age, sex (male = 1, female = 2), preference for drama, and whether participants have children (=1) or not (=0). The indirect effects of identity threat were examined by bootstrap analyses with 5,000 bootstrap samples and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals. Identity threat was a positive, significant predictor of boundary expansion after controlling for age, sex, drama preference, whether they had children or not, and stimulus film, B = 0.49, SE = 0.12, p < .001. Next, boundary expansion significantly predicted appreciation (H2a), B = 0.31, SE = 0.05, p < .001, transportation (H2b), B = 0.31, SE = 0.04, p < .001, fun enjoyment (H2c), B = 0.26, SE = 0.06, p < .001, and character identification (H2d), B = 0.36, SE = 0.05, p < .001. The bootstrapped confidence intervals for the indirect effects of identity threat did not include zero for any of these four dependent variables: B = 0.15, SE = 0.05, 95% CI from 0.070 to 0.251 (appreciation), B = 0.15, SE = 0.04, 95% CI from 0.079 to 0.242 (transportation), B = 0.12, SE = 0.04, 95% CI from 0.055 to 0.221 (fun enjoyment), and B = 0.18, SE = 0.05, 95% CI from 0.089 to 0.281 (character identification). In other words, greater pandemic-induced identity threat was associated with higher boundary expansion, which in turn, enhanced film appreciation, narrative transportation, fun enjoyment of the film, and character identification. Thus, H2a to H2d were all supported. Table 4 reports regression coefficients and standard errors for all direct effects.

| Variables . | Appreciation . | Transportation . | Fun enjoyment . | Character identification . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . |

| Age | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) |

| Sex | −0.12 (0.20) | −0.12 (0.18) | −0.16 (0.23) | −0.56 (0.20)** |

| Drama preference | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.06 (0.09) | 0.12 (0.08) |

| Children | 0.61 (0.22)** | 0.35 (0.19) | 0.54 (0.24)* | 0.72 (0.21)*** |

| Stimulus film | 1.04 (0.21)*** | 0.50 (0.18)* | −1.22 (0.23)*** | 0.81 (0.20)*** |

| Identity threat | 0.12 (0.08) | 0.03 (0.07) | −0.05 (0.09) | −0.04 (0.08) |

| Boundary expansion | 0.31 (0.05)*** | 0.31 (0.04)*** | 0.26 (0.06)*** | 0.36 (0.05)*** |

| F (df) | 16.89(7,164)*** | 13.40(7,164) *** | 7.67(7,164) *** | 19.68(7,164)*** |

| R2 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.46 |

| Variables . | Appreciation . | Transportation . | Fun enjoyment . | Character identification . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . |

| Age | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) |

| Sex | −0.12 (0.20) | −0.12 (0.18) | −0.16 (0.23) | −0.56 (0.20)** |

| Drama preference | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.06 (0.09) | 0.12 (0.08) |

| Children | 0.61 (0.22)** | 0.35 (0.19) | 0.54 (0.24)* | 0.72 (0.21)*** |

| Stimulus film | 1.04 (0.21)*** | 0.50 (0.18)* | −1.22 (0.23)*** | 0.81 (0.20)*** |

| Identity threat | 0.12 (0.08) | 0.03 (0.07) | −0.05 (0.09) | −0.04 (0.08) |

| Boundary expansion | 0.31 (0.05)*** | 0.31 (0.04)*** | 0.26 (0.06)*** | 0.36 (0.05)*** |

| F (df) | 16.89(7,164)*** | 13.40(7,164) *** | 7.67(7,164) *** | 19.68(7,164)*** |

| R2 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.46 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

| Variables . | Appreciation . | Transportation . | Fun enjoyment . | Character identification . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . |

| Age | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) |

| Sex | −0.12 (0.20) | −0.12 (0.18) | −0.16 (0.23) | −0.56 (0.20)** |

| Drama preference | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.06 (0.09) | 0.12 (0.08) |

| Children | 0.61 (0.22)** | 0.35 (0.19) | 0.54 (0.24)* | 0.72 (0.21)*** |

| Stimulus film | 1.04 (0.21)*** | 0.50 (0.18)* | −1.22 (0.23)*** | 0.81 (0.20)*** |

| Identity threat | 0.12 (0.08) | 0.03 (0.07) | −0.05 (0.09) | −0.04 (0.08) |

| Boundary expansion | 0.31 (0.05)*** | 0.31 (0.04)*** | 0.26 (0.06)*** | 0.36 (0.05)*** |

| F (df) | 16.89(7,164)*** | 13.40(7,164) *** | 7.67(7,164) *** | 19.68(7,164)*** |

| R2 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.46 |

| Variables . | Appreciation . | Transportation . | Fun enjoyment . | Character identification . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . |

| Age | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) |

| Sex | −0.12 (0.20) | −0.12 (0.18) | −0.16 (0.23) | −0.56 (0.20)** |

| Drama preference | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.06 (0.09) | 0.12 (0.08) |

| Children | 0.61 (0.22)** | 0.35 (0.19) | 0.54 (0.24)* | 0.72 (0.21)*** |

| Stimulus film | 1.04 (0.21)*** | 0.50 (0.18)* | −1.22 (0.23)*** | 0.81 (0.20)*** |

| Identity threat | 0.12 (0.08) | 0.03 (0.07) | −0.05 (0.09) | −0.04 (0.08) |

| Boundary expansion | 0.31 (0.05)*** | 0.31 (0.04)*** | 0.26 (0.06)*** | 0.36 (0.05)*** |

| F (df) | 16.89(7,164)*** | 13.40(7,164) *** | 7.67(7,164) *** | 19.68(7,164)*** |

| R2 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.46 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

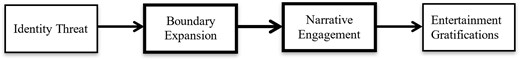

Post hoc path analyses were conducted via maximum likelihood estimation using Amos 18 (Arbuckle, 2009) to compare the two different causal orderings of boundary expansion and narrative engagement in the model proposed in H2. In the first path analysis, the predictor was identity threat, followed by boundary expansion as the first mediator and both transportation and identification as a set of downstream mediators; fun enjoyment and appreciation (with the two subscales collapsed into one) were the final outcomes, and direct paths were also drawn between the predictor and these two outcomes. Further, all five control variables from the previous analysis were included. Additionally, transportation and identification were allowed to covary, as were enjoyment and appreciation, because they are conceptually related, respectively. For the first path analysis, where boundary expansion precedes engagement, the model fit was good: χ2 = 4.34, df = 4, p = .36, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.02 (90% CI: 0.000 to 0.120), SRMR = 0.01 (Hu & Bentler, 1998). A second path analysis was conducted where the order of the first-step and second-step mediators were reversed, such that the engagement variables (transportation and identification) preceded boundary expansion; the arrangement of the other variables remain identical to the initial path analysis. This second path analysis showed poor model fit: χ2 = 150.76, df = 5, p < .001, CFI = 0.77, RMSEA = 0.41 (90% CI: 0.358 to 0.471), SRMR = 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1998). In short, these path analysis results support the theorized causal ordering in the TEBOTS model where self-expansion precedes engagement (see Figure 1).

The theorized causal ordering of self-expansion and engagement in the TEBOTS model.

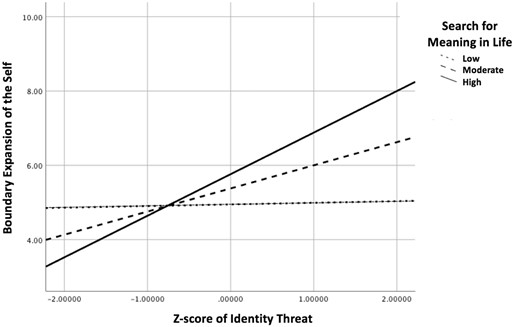

H3: The indirect effects of identity threat on appreciation, transportation, fun enjoyment, and identification reported above were examined for low, moderate, and high levels of search for meaning-in-life. Model 7 (Hayes, 2012) was used to calculate the bootstrapped confidence intervals for the indirect effects at the 16th (2.00 out of 7.00; low), 50th (4.00 out of 7.00; moderate), and 84th (6.00 out of 7.00; high) percentiles of search for meaning-in-life with 5,000 bootstrapped samples.

First, the effect of pandemic-based identity threat on boundary expansion via story exposure was significantly moderated by the tendency to search for meaning-in-life, after controlling for the individual differences and stimulus film, B = 0.15, SE = 0.06, p = .01. Identity threat was a positive predictor of self-expansion for those who have a high or moderate tendency to search for meaning-in-life, but this effect became negligible for those who have low levels of search for meaning-in-life (Figure 2). The follow-up bootstrapped analysis confirmed that the positive indirect effects of identity threat on film appreciation, transportation, fun enjoyment, and character identification reported in H2 were significant for those who scored moderate or high in search for meaning-in-life. In contrast, for those who scored low in search for meaning-in-life, identity threat did not exert any indirect effects through boundary expansion (Table 5).

The Conditional Indirect Effects of Identity Threat Through Boundary Expansion

| . | Appreciation . | Transportation . | Fun enjoyment . | Character identification . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Search for meaning in life . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . |

| 95% CI . | 95% CI . | 95% CI . | 95% CI . | |

| Low | 0.01 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.07) |

| −0.112 to 0.128 | −0.122 to 0.123 | −0.097 to 0.117 | −0.129 to 0.151 | |

| Moderate | 0.10 (0.04) | 0.11 (0.04) | 0.09 (0.04) | 0.12 (0.05) |

| 0.025 to 0.196 | 0.022 to 0.193 | 0.016 to 0.179 | 0.027 to 0.229 | |

| High | 0.20 (0.06) | 0.20 (0.06) | 0.17 (0.06) | 0.24 (0.07) |

| 0.089 to 0.333 | 0.088 to 0.335 | 0.069 to 0.294 | 0.110 to 0.378 |

| . | Appreciation . | Transportation . | Fun enjoyment . | Character identification . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Search for meaning in life . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . |

| 95% CI . | 95% CI . | 95% CI . | 95% CI . | |

| Low | 0.01 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.07) |

| −0.112 to 0.128 | −0.122 to 0.123 | −0.097 to 0.117 | −0.129 to 0.151 | |

| Moderate | 0.10 (0.04) | 0.11 (0.04) | 0.09 (0.04) | 0.12 (0.05) |

| 0.025 to 0.196 | 0.022 to 0.193 | 0.016 to 0.179 | 0.027 to 0.229 | |

| High | 0.20 (0.06) | 0.20 (0.06) | 0.17 (0.06) | 0.24 (0.07) |

| 0.089 to 0.333 | 0.088 to 0.335 | 0.069 to 0.294 | 0.110 to 0.378 |

The Conditional Indirect Effects of Identity Threat Through Boundary Expansion

| . | Appreciation . | Transportation . | Fun enjoyment . | Character identification . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Search for meaning in life . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . |

| 95% CI . | 95% CI . | 95% CI . | 95% CI . | |

| Low | 0.01 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.07) |

| −0.112 to 0.128 | −0.122 to 0.123 | −0.097 to 0.117 | −0.129 to 0.151 | |

| Moderate | 0.10 (0.04) | 0.11 (0.04) | 0.09 (0.04) | 0.12 (0.05) |

| 0.025 to 0.196 | 0.022 to 0.193 | 0.016 to 0.179 | 0.027 to 0.229 | |

| High | 0.20 (0.06) | 0.20 (0.06) | 0.17 (0.06) | 0.24 (0.07) |

| 0.089 to 0.333 | 0.088 to 0.335 | 0.069 to 0.294 | 0.110 to 0.378 |

| . | Appreciation . | Transportation . | Fun enjoyment . | Character identification . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Search for meaning in life . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . | B (SE) . |

| 95% CI . | 95% CI . | 95% CI . | 95% CI . | |

| Low | 0.01 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.07) |

| −0.112 to 0.128 | −0.122 to 0.123 | −0.097 to 0.117 | −0.129 to 0.151 | |

| Moderate | 0.10 (0.04) | 0.11 (0.04) | 0.09 (0.04) | 0.12 (0.05) |

| 0.025 to 0.196 | 0.022 to 0.193 | 0.016 to 0.179 | 0.027 to 0.229 | |

| High | 0.20 (0.06) | 0.20 (0.06) | 0.17 (0.06) | 0.24 (0.07) |

| 0.089 to 0.333 | 0.088 to 0.335 | 0.069 to 0.294 | 0.110 to 0.378 |

RQ1: Model 4 of the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2012) examined RQ1. Identity threat was entered as the independent variable, and boundary expansion as the mediator. This analysis controlled for stimulus film (1 = tragedy, 0 = comedy), age, sex (male = 1, female = 2), preference for drama, and whether they have children (=1) or not (=0). The indirect effect of identity threat on the tendency to find positive meaning in the pandemic was examined by a bootstrap analysis with 5,000 samples and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals.

Results showed that identity threat was a positive predictor of boundary expansion, B = 0.50, SE = 0.12, p < .001, after controlling for individual differences and stimulus film.1 Next, boundary expansion of the self was positively associated with finding positive meaning in the pandemic, B = 0.11, SE = 0.03, p < .001. The follow-up bootstrap analysis showed that identity threat exerted a positive indirect effect on finding positive meaning through boundary expansion, B = 0.05, SE = 0.02, 95% CI from 0.02 to 0.10. In other words, participants who felt greater identity threat from the pandemic experienced greater boundary expansion during movie watching regardless of stimulus film, which, in turn, encouraged them to find more positive meaning in the pandemic. In addition, the direct effect of identity threat on finding positive meaning was also significant. Not surprisingly, those who experienced greater identity threat were less likely to find positive meaning in the pandemic if it were not for the mediating effect of boundary expansion, B = −0.13, SE = 0.04, p < .01. Drama preference and stimulus film were also significant predictors of finding positive meaning in the pandemic. Those who have a greater preference for drama were more likely to find positive meaning in the pandemic, B = 0.09, SE = 0.04, p < .05, and those who watched a comedic film showed a greater tendency to find positive meaning in the pandemic as well, B = −0.26, SE = 0.11, p < .05.

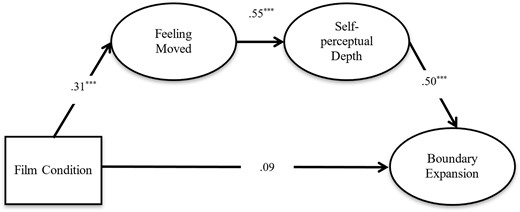

RQ2: Path analyses with maximum likelihood estimates were generated using AMOS 18 to explore the mechanisms of feeling moved and self-perceptual depth (downstream) in the relationship between tragedy exposure and boundary expansion. This two-step mediation process included identity threat as a control variable. All mediators and the dependent variable were modeled as latent constructs with single indicators and corrected for measurement error using the estimate σ2×(1−α); film condition and identity threat were treated as exogenous variables. Film condition was coded as tragedy (1) or comedy (0). The model fit was good: χ2 = 1.41, df = 2, p = .50, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00 (90% CI: 0.000 to 0.137), SRMR = 0.01 (Hu & Bentler, 1998).

Every mediating path in the two-step mediation model, from film condition to boundary expansion through feeling moved and self-perceptual depth, was statistically significant (see Figure 3). The direct effect from film condition to boundary expansion was not significant (β= 0.09, n.s.). However, the total effect of film condition on self-expansion was significant (β= 0.17, p < .05). Next, a mediation test was conducted using bootstrapped procedures with 5,000 bootstrap samples and bias-corrected confidence intervals; in the model, the indirect effect was tested in the presence of the direct path between the main predictor and outcome. The indirect effect from tragic film to self-expansion was positive and significant (β= 0.08, p < .01). In short, compared to comedy, tragic drama raised self-expansion when it was fully mediated by feeling moved and self-perceptual depth.

The mediation model (RQ2) with standardized path coefficients.

Notes: † differ at p < .1, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. For film condition, tragedy was coded as 1 and comedy was coded as 0. This model controlled for identity threat in a pandemic.

Discussion

The results from testing the first two sets of hypotheses were conceptual replications of the findings of previous TEBOTS studies that tested its central predictions (Johnson et al., 2015, 2016). Specifically, identity threat in a pandemic was positively associated with temporary self-expansion, narrative transportation, and film appreciation, whereas self-expansion, as a mediator, explained the link between identity threat and both narrative engagement and entertainment gratifications. The present findings provide additional evidence for the prediction that the demands on personal and social identity raise the degree of story engagement and satisfaction because stories provide the psychological relief that arises from the temporary expansion of the boundaries of the self. The present research contributes to the TEBOTS literature by examining the validity of the concept of threat to identity in its direct relationship with boundary expansion via story exposure. To our knowledge, the current work is the first study to integrate theories of personal and social identity threat to the TEBOTS model and construct a new scale to measure identity threat in the context of boundary expansion.

The results of the path analyses that examined the causal ordering of boundary expansion and engagement show encouraging evidence in support of TEBOTS processes that were proposed by Slater et al. (2014). Theoretically, the TEBOTS model assumes that boundary expansion is a foundational psychological process in the interplay between the self and stories. Consequently, these results provide initial empirical evidence for the fundamental nature of temporary self-expansion in the study of the appeal of stories. Boundary expansion may be more rudimentary than the processes of narrative engagement. However, further corroboration is needed to establish the causal order of self-expansion and narrative engagement because the current study design lacks time precedence in the manner in which these variables were observed. A future study should measure self-expansion during story exposure, as suggested by Johnson et al. (2016), to seek further evidence for its causal precedence over story engagement. Thus, further testing is required to show that the key assumption of the centrality of self-expansion in the TEBOTS model is empirically supported.

The present study also addresses open questions from past TEBOTS research. Whereas a previous study discussed the potential limitations of the TEBOTS model because an individual difference (i.e., a motive to search for meaning in life) was needed to moderate the effects of self-threat on boundary expansion (Johnson et al., 2016), the direct association found via H1a shows that this additional motivation for self-expansion may not be necessary when self-demands are adequately robust. Participants’ sense of identity threat amid the pandemic remained significantly associated with boundary expansion after controlling for other individual differences. A likely explanation for the differences between the present results and the null findings in Johnson et al. (2016) is the larger variance in identity threat during a public event compared to the well-documented small effects of the self-affirmation task used in the latter (Epton et al., 2015). Further, the present study confirmed that individuals who are high in search for life meaning could indeed become more absorbed and satisfied with story exposure by experiencing greater boundary expansion (H3), which conceptually replicates a finding in the previous work; in both the present study and Johnson et al. (2016), those low on search for meaning did not exhibit this link. Interestingly, those with only moderate levels of search for meaning also exhibited a significant relationship between identity threat and self-expansion in the current study. This additional finding, which diverges slightly from those in the Johnson et al. (2016) experiment, suggests that the greater degree of soul-searching during a troubling pandemic may have motivated even those with an average level of search for life meaning to experience boundary expansion from story engagement as a means of momentary relief from identity demands. Overall, identity threat in a pandemic affects TEBOTS processes and outcomes in a predictable manner.

The present study makes further contributions to the TEBOTS literature by showing that boundary expansion through stories can encourage positive coping with a public crisis that raises identity demands. The COVID-19 pandemic has put many lives on hold for health and economic reasons, which, in turn, created a sense of loss of a previous way of life. However, the mediation of self-expansion on finding positive meaning (RQ1) shows that TEBOTS processes may have encouraged viewers to grapple with their pandemic-related troubles in a fruitful way. Previous research supports this interpretation. A recent U.S. survey on pandemic experiences found that positive reframing of the public crisis suppresses the negative indirect effect of anxiety on affect (Eden, Johnson, Reinecke, & Grady, 2020). Indeed, without undergoing self-expansion, the threatened self perceives the pandemic as an adversity; the direct effect of identity threat on finding positive meaning was in the negative direction. In bereavement research, finding positive meaning is an indicator of posttraumatic growth (Fredrickson et al., 2003). Consequently, boundary expansion during narrative exposure provides audiences with a way to reevaluate the pandemic so that they no longer perceive the pandemic as an utter misfortune. This positive indirect relationship suggests that TEBOTS processes can help individuals cope with their identity-threatening experiences by creating the psychological space for reappraising those self-threatening events in a more positive light. These results are consistent with research on selective exposure where some viewers who feel sad were more interested in sad genres because they expected “cognitive gains and growth” (Kim & Oliver, 2013, p. 383). In short, boundary expansion may benefit the individual who is undergoing negative experiences by providing opportunities for positive reframing or meaning-making.

The examination of indirect effects of identity threat on finding positive meaning also yielded incidental findings related to genre preferences and exposure to light comedy. These results show that other processes aside from boundary expansion could also explain the effects of story exposure on finding positive meaning. First, a positive relationship between preferences for drama and finding positive meaning was found. This result suggests that individuals who prefer nonhedonic genres were likely more open to reflect on issues concerning human struggles in the first place and, regardless of the stimulus film they were exposed to, were able to cope with and make positive meaning from the pandemic. Second, the link between fun comedy exposure and finding positive meaning may be explained by the concept of escapism. Light-hearted comedies may provide a degree of short-term escape from real-world anxieties that permit the individual to feel more cheerful while reevaluating their lives with greater hope amidst the pandemic. Future research should consider testing boundary expansion against competing explanations for the impact of identity threat on finding positive meaning, including escapism.