-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sarah Tribout-Joseph, Updating Victor Hugo for the Twenty-First Century: Addressing Entrenched Inequality, Discrimination and Police Violence in Ladj Ly’s Banlieue Film, Les Misérables (2019), Forum for Modern Language Studies, Volume 60, Issue 4, October 2024, Pages 447–468, https://doi.org/10.1093/fmls/cqae080

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In the same time that it took France to win the 2018 World Cup final, Ladj Ly’s film, Les Misérables (2019), takes viewers from jubilant football crowd scenes to protest in the streets. Produced as a response to the 2005 riots in France, Ly takes an urgent look at inequality and police violence in the banlieue or impoverished suburbs. His aim is both to debunk the Republic’s claim to universalism and to contest the representation of the banlieue in mainstream media and banlieue film. I argue that in claiming heritage from Victor Hugo, Ly explores the effectiveness of various media platforms for challenging social exclusion in the high-rise estates on the margins of the city, with their large immigrant populations. I look firstly at Republican values and marginalization in the banlieue, before considering banlieue film and how Les Misérables moves from nineteenth-century literature to twenty-first century digital activism in order to embrace a more inclusive society.

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement galvanized support worldwide after the high-profile killing of George Floyd, an unarmed black man, by a white police officer kneeling on his neck in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 2020. Filmed by witnesses on their mobile phones, the victim repeatedly appealed to officers, telling them that he could not breathe. Footage of the incident went viral and led to global condemnation and eventually to the conviction for murder of the white police officer, Derek Chauvin, who was sentenced to twenty-two years imprisonment. J. Alexander Kueng, Tou Thao and Thomas Lane also received sentences for depriving Floyd of his civil rights and Kueng and Thao received further sentences for failing to give medical aid and failing to stop Chauvin from using excessive force.1

This historic capture of police brutality on film is foreshadowed by Ladj Ly’s fictional film, Les Misérables (2019), in which the shooting of an unarmed child by a police officer is caught on camera by a drone, which the three officers at the scene subsequently try to cover up. Asked in an interview about the resonance of his film with the recent tragedy, Ly saw such events as sadly commonplace, arguing that such police brutality is nothing new: ‘The BLM movement was inevitable. The situation in France has long been at a critical point. The fight against racism and police violence was never visible enough’.2 Ly links the film to France’s own variation of the BLM movement in response to the death of a French man of Malian descent, Adama Traoré, who died in 2016 in Beaumont-sur-Oise, north of Paris, whilst in police custody. Backed by independent medical reports, the family, and in particular his sister, Assa Traoré, have sought to prove that he died under the weight of the three police officers restraining him. The defendants deny any criminal offence and were acquitted in 2020, sparking widespread protests in major cities across France and resonating with the BLM movement in America.3 Controversy in France about police violence also centres on the use of flashball or ‘less-lethal’ guns for riot control. Such guns have proved fatal and are illegal elsewhere in Europe. Billed as ‘the new La Haine’ [Hate], (Mathieu Kassovitz’s 1995 genre-defining film on social deprivation in the banlieue or marginalized neighbourhoods), Ladj Ly’s recent update of this film and of Victor Hugo’s novel will be taken here as a case study which highlights the continued urgency of addressing entrenched inequality and police violence in the banlieue.

One important departure from the issues raised by the BLM movement or its counterpart French movement sparked by the Traoré case is that in the fictional film, Les Misérables, the officer who fires the shot is black. By making the officer black, Ly downplays the issue of race to focus instead on social deprivation, although the two questions are interrelated.4 Ly further shifts the focus away from ethnicity by making the lead character the white police officer, Stéphane Ruiz. As Karolina Westling writes, ‘Les Misérables is not framed from the perspective of an ethnic Other or a banlieusard, as might have been the expected choice by a director with Ly’s background’.5 By making the main character a ‘good cop with pale skin’, Ly makes it ‘easy for a larger audience to engage with the film’.6 This development can be traced back to La Haine, with Ginette Vincendeau arguing that Kassovitz emphasized socio-economic exclusion over race and religion.7 Alec Hargreaves argues that since La Haine, the ‘ “Black-Blanc-Beur” [Black-White-Arab] trio of buddies is now a lieu commun of popular culture’ but he goes on to show that there is also intense rivalry between ethnic groups.8 The term ‘Black-Blanc-Beur’ refers to the ethnically diverse French team that won the 1998 football World Cup and Ly’s film foregrounds the importance of football in popular culture and politics, as will be seen.

As the title suggests, Les Misérables is a contemporary reinterpretation of Hugo’s nineteenth-century novel. It is Ly’s first feature film and has been met with critical acclaim winning, amongst other prizes, the 2019 Jury Prize at Cannes and a César for the best film in 2020, as well as an Oscar nomination. Transposing the story of Les Misérables into a different medium for the twenty-first century, I will argue, highlights the value of camera footage as evidence and self-defence in the face of police brutality and systemic discrimination. Set in the high-rise estate, or cité, of Les Bosquets in Montfermeil in Seine-Saint-Denis on the outskirts of Paris, the film combines fictional and documentary elements, to bring everyday life in these quartiers sensibles [problem estates], as they are often called in the media, into the spotlight.9 The film was inspired by the 2005 riots which were triggered by the deaths of the two teenagers, Zyed Benna and Bouna Traoré, who were electrocuted in a substation in the banlieue of Clichy-sous-Bois, having fled from a police identity check. At the time, the events ‘were covered by the media in ways that obscured police racism, emphasising instead the supposed criminality and/or radicalisation of those involved in the riots’.10 As viewers of Les Misérables, we enter into the cité alongside Stéphane, the new recruit to the Brigade anti-criminalité (BAC) [Anti-Crime Squad], who joins his colleagues, Chris and Gwada, who have become desensitized to their surroundings. The theft of a lion cub from the circus by the young banlieusard, Issa, leads to his arrest, which ends with Issa being shot in the face with a flashball. The resulting cover-up operation inflames the outraged local community and threatens to ignite riots in the suburbs.

In this article, I will begin by examining the concept and everyday reality of the banlieue and the spatialization of politics, and how the film contests the Republic’s claims to universalism in depicting this reality. The film could be seen as an example of Laurent Dubreuil’s notion of a ‘poetics of banlieue’, in which the ‘tendency toward the confiscation of the speech of the colonized’,11 is both ‘reproduce[d] and displaced’ by bypassing usual ‘parlance’.12 In his analysis of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet’s film on the 2005 riots, Europa 2005 –27 octobre, Dubreuil suggests that the ‘image-words, shared by anonymous taggers […], may open up a new (troubling, violent) poetics of banlieue, far away from the conventions of ready-made speeches and the small talk of experts or politicians’.13 Similarly, there is a poetic reconfiguration of silence in the freeze frame at the end of Ly’s film, the cri of anger in the roar of the lion, and the anonymous tags on the stairwell that suggest revolt (‘LA NUIT JE RODE’) [I roam the night]. I will then look at how, in seeking alternative weapons to violence in the call to arms, the film explores various media as platforms on which to fight. I will argue that Ly advocates using a variety of media and social media platforms to explore identity and voice protest and in so doing, offers a reworking of Hugo’s novel for the twenty-first century and a reflection on the challenge of making literature relevant and accessible. By borrowing Hugo’s title for the film, Ly inscribes the film in the aesthetic tradition of social realism whilst also challenging us to reflect upon not just Republican values, but also the distinction between what Pierre Bourdieu calls ‘legitimate culture’ and an inclusive ‘culture of proximity’, a way of accessing culture and exploring identity based on our everyday worlds.14

Republican values and the ‘banlieue’

The jubilant mood at the beginning of Les Misérables is in stark contrast to the mood at the end of the film. The film opens with a medium shot of Issa, a small adolescent of childlike stature, draped in the French tricolour flag with the colours of the flag daubed on his face. The setting is the summer of 2018 and the French World Cup victory over Croatia. Issa meets his friends at the bus stop and they discuss whether their hero, Kylian Mbappé, will score. The group then takes the RER train from the suburbs into central Paris to participate in the big-screen showing of the final. Medium long shots show the group of boys in front of the Eiffel Tower. A long shot of the Champs-Élysées shows a perfectly aligned Arc de Triomphe with a sea of red, white and blue. The iconic landmarks of the French Republic reflect the tide of national support and euphoria of the fans who have taken to the streets to celebrate their second World Cup victory.

Support for the French national team at the World Cup. Les Misérables, dir. by Ladj Ly (France, 2019), 3:11. Reproduced with permission of SRAB Films - Rectangle Productions - Lyly Films.

As Geoff Hare writes after the 1998 French World Cup win, ‘The phrase “black-blanc-beur” was created on the pattern of the national colours (bleu-blanc-rouge) to describe the special Frenchness of the team and the nation’s unity in diversity’.15 The team reflected the increasing ethnic diversity in French society. The football youth training schemes offered a way out of the entrapment of life in the banlieue to immigrants. As Patrick Mignon writes:

football players from immigrant communities excelled because for them the usual access to social mobility, through school and work were closed. What these players gave an earlier era of French football was the will to succeed and the desire to be recognised. The youth training schemes continue to attract disproportionately the children of immigrant families because they are encountering problems in the education system.16

Yet despite the success of these training schemes, the National Front leader Jean-Marie Le Pen famously criticized the racial composition of the French team.17 Indeed, in the film it is less the game and more the socio-political dimension that is of importance. We do not see the match; the cameras are turned instead on the crowd. The concept of performance and spectatorship is reinforced by the later arrival in town of the circus and the exploitation of the carnivalesque motif. The young protagonists, dressed in the colours of the flag and wearing red, white and blue face paint, participate in the show and the victory parade, singing the national anthem and voicing their support for the young Mbappé from the neighbouring high-rise estate of Bondy, also in Seine-Saint-Denis. As the police chief says, they believe for a day that ‘on est tous champion du monde’ [everyone is a World Cup winner]. For Mikhail Bakhtin, carnival is a day in which the tables are turned and anyone can be king or champion for a day.18 In the film, we see the boys jump over the turnstiles in the underground. On World Cup day, no one is going to argue about paying for the train. The usual barriers restricting access to Paris are removed, allowing the boys from the banlieue to participate, for once, in a national event and even imagine themselves as national heroes. However, as the police chief says, the euphoria is illusionary and there is the subsequent shock of returning to reality – a point which is ironically underlined in the film when Issa is arrested the next day whilst the boys are playing their own game of football. The botched arrest, the catalyst in the film, results in Issa being shot in the face.

In his provocative book on the function of sport, Barbaric Sport: A Global Plague, Marc Perelman argues that sport is a smokescreen behind which to hide inequality.19 The opening of Les Misérables belies the rest of the film, which deconstructs the suggested unity of the nation in the opening sequences. These are the only scenes that are shot outside the cité. Otherwise, the protagonists and the spectators are claustrophobically trapped in this marginalized space. Furthermore, a large percentage of the screen time is filmed in the cage d’escaliers – on the vandalized stairways, which symbolize not only the sense of being trapped, but also the lack of social mobility in these enclaves of deprivation within the Republic. Sequences that bookend the film serve to emphasize the fact that in the high-rise blocks the lifts, representing the possibility of social elevation, are invariably broken.

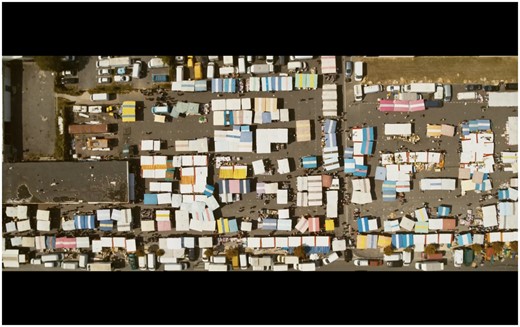

Since the French Revolution, the French Republic has been constructed around a set of shared values as the birthplace of the ‘Rights of Man’, as cherished in the motto ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’. Carrier Tarr argues that ‘Since the French Revolution, France has prided itself on being the land of equality, founded on an abstract concept of universal citizenship which renders ethnic, gendered, religious or class difference irrelevant’.20 This point is echoed by Mustafa Dikeç in Badlands of the Republic, when he argues that, whereas in Britain and the US the concepts of communities and multiculturalism are recognized, the ‘French republican tradition emphasizes a common culture and identity, and any reference to communities is deliberately avoided because they imply separatism, which is unacceptable under the principle of the “one and indivisible” republic’.21 In Les Misérables, the French Republican construction of identity is the starting point against which the rest of the film will position itself. A visually stunning moment in the film, one which encapsulates the richness and beauty of diversity, is offered in the high-angle aerial shot of the colourful mosaic of market stalls, allowing a moment of vision and respite from the everyday reality of disadvantage, discrimination and exclusion and the possibility of envisaging and valuing multiculturalism. This contrasts with the low-angle shots which characterize the genre and which emphasize the fact that the inhabitants are trapped in their high-rise estates. The film, however, highlights the Republic’s refusal of ethnic diversity. This is notable after Gwada speaks to Issa’s mother in their native language and gains her trust to allow a search of the apartment without a warrant. Chris, however, insists they should speak French, reaffirming the principle of assimilation.

The market. Les Misérables, dir. by Ladj Ly (France, 2019), 26:40. Reproduced with permission of SRAB Films - Rectangle Productions - Lyly Films.

Indeed as Dikeç argues, from the 1990s the term banlieue has increasingly become associated with interlinked feelings of insecurity and fear of immigration: ‘A term that once served simply to denote peripheral parts of urban areas has become a synonym of alterity, deviance, and disadvantage’.22 The English terms ‘suburb’ and French term ‘banlieue’ do not have the same connotations. There is, as Julia Dobson observes, ‘the suburb as an homogenous, dull enclave of detached housing and middle-class alienation, and the dominant post-1980 French profile of the suburb (banlieue) as high-density estates of tower blocks, predominantly immigrant populations, chronic unemployment and social unrest’.23 The first-generation of immigrants mainly lived in the shanty-towns that sprung up around the edge of large cities in the 1950s and 1960s. Charles de Gaulle cleared the shanty-towns in the 1960s, replacing them with the grands ensembles or high-rise estates of habitations à loyers modérés (HLM) [low-rent housing]. As has been the case for many of the cités, the planned infrastructure to link Montfermeil to nearby places of employment was abandoned, resulting in exclusion from the job market.24

Jacques Chirac won the 1995 presidential campaign on a ‘fracture sociale’ [social divide] ticket and the promise of bridging the divide, with a ‘plan Marshall des banlieues’ [Marshall Plan for the suburbs]. In reality, however, there was little change.25

Vincendeau analyses the prevalence of films which reinforce this sense of entrapment. She argues that there are two types of French banlieue film: those by auteurs such as Tati or Rohmer who try to avoid the label of ‘sociological film’ by emphasizing ‘a distancing aesthetic agenda’ and those which do focus on the sociological side.26 Within the latter she identifies a subgenre which ‘as well as reducing the concrete environment of the banlieue to the cité […] frequently boil down their inhabitants to groups of young men’.27 The carnivalesque scenes at the start of the Les Misérables, in which the boys jump the turnstiles and are allowed free entry into the city on World Cup day, contrast with a later scene at a bus stop. Three girls wait hopefully for a bus which never comes and they are instead the victims of an abusive police body search. The lack of social mobility is indicated by the fact that they are prevented from taking the bus – Chris tells them instead to go home. The girls are trapped on the estate in an abusive culture. If La Haine has raised the visibility of social deprivation in the banlieue and been identified with a new genre of film, hidden behind the portrayals of hypermasculinity, female inhabitants have further to go to achieve visibility, although recent films such as Céline Sciamma’s Bande de filles [Girlhood] (2014) and Houda Benyamina’s Divines [Divines] (2016) take up the challenge, as will be seen.

Banlieue inhabitants are further trapped by their negative representation in the media, as Dobson shows. This in turn reinforces the fears about radicalization and the threat to security which are used to justify repressive policing and the ‘legitimate’ use of violence:

Since the mid-1980s, in the context of high rates of (youth) unemployment, hostile policing and regressive political discourses of national identity and exclusion, the banlieues have been marked by high incidences of social fragmentation and unrest. Dominant media representations have aligned these built environments very closely with violent crime, social unrest and a discursive space constructed as alien to that of the values of the French Republic and its citizens.28

In La Psychose française, Mehdi Belhaj Kacem reinforces such a view, arguing that there is nothing new about threats to security; what is new is that the threat has been placed centre stage:

Le ‘sécuritaire’ popularisé en France, par la droite extrême, n’est pas un problème politique. Il y a toujours eu de la délinquance et de la pègre, aujourd’hui ni plus ni moins qu’hier. Ce qui est nouveau, c’est, plutôt que d’aviser aux nouveaux moyens de traiter la question, qu’on ait mis le problème en première ligne.29

[The popularization of ‘security’ in France by the far right is not a political issue. Mobs and delinquency have always existed, and are no more prevalent today than in the past. What is new is that rather than thinking about new ways of addressing the issue, the focus has been on the problem itself.]

Writing in response to the 2005 riots, he argues that terrorism and security threats, rather than menacing democracy, actually sustain it by deflecting criticism: ‘Le terrorisme; loin de la menacer [la démocratie], il est le gage ultime de son maintien perpétuel; puisqu’elle n’aura jamais plus à être jugée sur ses résultats, mais sur ses ennemis’ [Far from threatening democracy, terrorism is the ultimate guarantee of its continued existence, allowing it to be judged not against its results but against its enemies].30 This heightened state of alert is perpetuated through negative media coverage: ‘La démocratie ne subit donc pas simplement une ‘crise’, mais est maintenue, par la perfusion médiatique, en survie artificielle’ [Democracy is therefore not simply in crisis, but is itself being artificially kept alive by the media drip feed].31 In his analysis of exclusion, he recalls that the word ‘banlieue’ originated to analyse ‘le ban’, or the banishment of the banlieusard from the Republic.

In using critical theory to speak up for the marginalized, Jacques Rancière defines the police as a ‘system of distribution and legitimation’: ‘the organization of powers, the distribution of places and roles, and the systems for legitimizing this distribution’.32 ‘Politics’ is the term Rancière reserves for anything that challenges this established order. ‘Dissensus’ is the name he gives to the claim by those who are excluded by the system from their share in the world, in the policed order of the world. Inspired by the 2005 riots, Les Misérables, like many banlieue films, explores this clash between the established order, headed up by the police – as Chris says ‘c’est moi la loi’ – and the marginalized. In considering how relations between the police and young people maintain or challenge power relations, Jonathan Ervine, by contrast to Rancière, makes allowances for the fact that:

Given existing negative stereotypes that associate French banlieues with crime and violence, finding a way to depict relations between young people and the police in these areas that does not to some degree perpetuate these clichés provides film-makers with a challenge.33

Ly’s portrayal of the police is not entirely unsympathetic. Stéphane is shown to have a moral compass and Ly’s goal is not to stir up violent protest, but rather to find a channel for addressing justified resentment for maltreatment and profiling.

The ‘banlieue’ film and documentary form

Ly seeks to counter the image of the banlieue portrayed in the media but could arguably still be seen to subscribe to certain clichés. As a genre, the banlieue film first came into being in the 1990s, as Carrie Tarr observes, as ‘a series of independently released films set in the rundown multi-ethnic working class estates on the periphery of France’s major cities’, and headed up by Kassovitz’s La Haine (1995).34 The film brings social exclusion to our attention, as Tarr writes; ‘La Haine, with its central black-blanc-beur trio of unemployed youths, brought the representation of the banlieue and the fracture sociale (the increasing disparity between haves and have-nots in contemporary French society) to the centre of the cinematic viewing experience’.35 The inclusion of the white character in Kassovitz’s film is slightly more complicated as by making the character Jewish and not ‘straightforwardly white’ he ‘counters the reductive view of a “white republican Frenchness” that would be monolithically opposed to immigrants of African origin’, as Vincendeau writes.36 Asked about the line of affiliation to Kassovitz’s La Haine (1995), Ly replied that ‘What’s sad is that my film needed to be made. Things have clearly not changed in France between La Haine 25 years ago and Les Misérables now’.37 Recent scholarship on the banlieue film has criticized the reductive focus on the ‘difficult’ banlieue, with Vincendeau arguing that ‘The marginalisation of the banlieue and its inhabitants has been in no small measure exacerbated by audiovisual representations’.38 She analyses how the ‘mytheme’ of the ‘difficult’ suburb has become entrenched:

the films de banlieue endowed the topos of the difficult suburb with a consistent architectural and spatial iconography: high-rise estates dominated by towers (tours) and long blocks (barres), run-down staircases, graffiti, broken lifts, grim cellars and a cultural void signified by semi-derelict open spaces. Narratives privilege violence – riots, gunfights between gangs, clashes with the police and multiple social problems: unemployment, poverty, drugs and racism.39

She notes that clothing (sportswear, hoodies) and language (verlan or back slang in which syllables in a word are transposed to produce neologisms) are also codified. Vincendeau thus confirms David-Alexandre Wagner’s earlier findings in his extensive survey of banlieue film.40 In looking beyond the topos of the ‘difficult’ banlieue, Vincendeau explores what has been termed the ‘female banlieue’ film in works such as Tout ce qui brille (Géraldine Nakache and Hervé Mimran), Paulette (Jérôme Enrico), Bande de filles (Céline Sciamma) and Divines (Houda Benyamina), which she notes are still set against the backdrop of the high-rise estates. She concludes her study with a look at the quiet banlieue pavillonaire, or leafy suburbs. Similarly, in tracing the emergence of what he terms ‘post-beur’ cinema,41 Will Higbee argues that banlieue film in the 1990s had become ‘trapped within the essentialist categories of beur and banlieue filmmaking that had become over-determined from without’.42 He argues that the 2000s have been transformative for directors of Maghrebi origin with their ‘refusal to be confined to the perceived ghetto of beur and banlieue filmmaking’.43 He argues that diasporic directors have made extensive use of music ‘in a complex matrix of national, transnational and ‘glocal’ identity positionings’, Malik Chibane’s use of hip-hop being a case in point.44 ‘Post-beur’ directors, he argues, cannot be confined solely within a postcolonial or diasporic optic.45

Certainly though, for a long time, one of the defining features of the banlieue film genre was that is has been low-budget and on the margins of the mainstream. Many of the actors are non-professionals. In contrast to the atmospheric aerial or long shots, which are more removed from the action, the use of the Steadicam makes for more immersive viewing at street level and in the tight hemmed-in spaces on the narrow stairways. Unlike Kassovitz, who is white and from Paris, Ly is filming the place in which he grew up in the 1980s as an immigrant from Mali and where his father was a refuse collector (although as discussed earlier, Vinz is Jewish and indeed Kassovitz’s own father was Jewish and of Hungarian origin). Ly had in fact already filmed Les Bosquets in a court métrage, or short film, also called Les Misérables (2017) and in the earlier 365 jours à Clichy-Montfermeil (2006), immediately following the riots. He founded the film collective ‘Kourtrajmé’, verlan for short film. Given the low-budget status, and ‘Indicative of its position outside the mainstream of French cinema, Kourtrajmé typically bypassed the usual channels of distribution, preferring to post its creations online’.46 Danny Leigh reports that the feature film was made for just 1.4 million euros.47 Rather than being commercially driven, the documentary element of the film is true to John Grierson’s belief that documentary making should be socially useful storytelling.

Recent critics such as Vincendeau and Higbee have argued that the banlieue film as a genre is reductive, reinforcing stereotypes and compounding the negative image of the banlieue. Dobson argues that the genre is caught in a double bind, which perpetuates what it seeks to expose:

The dynamics of a double determinism – in which the diegetic space of the onscreen banlieue is seen to determine the fate of the characters and the filmic representation is seen to function as documentary ‘reality’ suggests that a pre-established perception of the nature of the banlieue leads to the privileging of particular characteristics to form a self-fulfilling genericity.48

Vincendeau argues that the former Prime Minister Alain Juppé’s compulsory screening of La Haine for his ministers confirms such a correlation.49 Similarly, Ladj Ly wanted his film to be seen by President Macron, who was apparently appalled and launched an inquiry.50 Designed by Le Corbusier but having become a symbol of ghettoization, the last block on the estate has now been demolished.51 Le Corbusier’s model of the ‘unité d’habitation’ [living unit] (later referred to as ‘des cages à lapins’ or rabbit hutches), which first appeared in Marseille from 1947 to 1952, became the blueprint for high-rise estates or projects across the world. As Johny Pitts writes:

Both Haussmann and Le Corbusier were ahead of their time and appear to have had good intentions, but between them they created a landscape perfect for breeding angst in poor communities. Through his luxurious housing ideals Haussmann first pushed the poor out of the heart of the city, and then, with depressing austerity and modernist experimentation, Le Corbusier pushed them up into the sky, into faceless concrete cages sandwiched on top of one another, later left to fall into decay by the state.52

La Haine has in any case certainly been effective in putting the plight of the banlieue on the public agenda.

What banlieue films have in common, as Tarr argues in retaining the term, is ‘a concern with the place and identity of the marginal and excluded in France’.53 Produced in part as a response to the 2005 riots, Les Misérables fulfils one of the genre’s defining characteristics of contesting the Republic and protesting against police violence. In disputing the idea of the one and indivisible Republic, and offering instead a vision of a multicultural society, the film explores the question of identity. In their article, ‘Beyond “Identity”’, Rogers Brubaker and Frederick Cooper propose breaking down the ‘all-purpose’, overused and analytically unworkable term ‘identity’.54 They are critical of both hard meanings of identity, which place people in essentialist categories, and soft meanings of identity, which are too fluid to be meaningful, ‘so infinitely elastic as to be incapable of performing serious analytical work’.55 Instead, they explore the merits of other terms such as ‘identification’, which is processual and less reifying than ‘identity’, or ‘commonality’, ‘connectedness’ and ‘groupness’ for collective identities or ‘self-understanding’, which they argue is also less reifying than identity. Ly tries to take us beyond a hard, essentialist definition of identity to a more nuanced definition which is sociological rather than exclusively based on ethnic difference. In particular, by making it the black officer who fires the gun, Ly avoids a strictly racialized reading and what John Murphy perceives as a ‘Pandora’s box of identity politics, ultimately cleaving French society into warring ethnic factions’.56

Yet banlieue films can be seen to conform to what Brubaker and Cooper refer to as weak or soft understandings of identity which build on ‘clichéd constructivism’.57 Kassovitz’s 1995 film, La Haine, which is generally taken as the ‘definitive banlieue film’, conforms to many stereotypes about drugs, delinquency and violence.58 Other films about the banlieue have focused on various aspects of identity and culture. Banlieue 13 [District 13] (Pierre Morel, 2004) explores the reappropriation of space in parkour. Ma 6-T va crack-er [My Suburbs are Going to Crack] (Jean-François Richet, 1997) combines rap-music and rioting. The music in Les Misérables, however, is predominantly techno by Pink Noise, rather than rap, and remains in the background. Apart from a rap by the man newly released from prison, it is always extra-diegetic and not part of the storyline.

Ly’s post-millennial film opens out less onto actual sounds and images as onto the possibility and potential of a vast archive of participatory internet footage and information, a virtual archive in every sense of the word. The film also prompts reflection on the uses and connections we ourselves make and the resonances of meaning that can be achieved; but, rather than looking to rap music for this as an expression of identity that has often been closely linked to the genre of banlieue film (alluded to in the way that the man who has been newly released from prison is still rapping and, according to Chris, is bound to reoffend), Ly appeals to more ‘high-brow’ culture, and to Hugo, to help challenge stereotypes and injustice.

The literary interface, the learning experience and participatory activism

In looking to redeem the film and the genre of the banlieue film from the charge of reductionism, I will look not to (rap) music as the genre characteristically does (although this is not of course inherently reductionist), but to literature and to the fact that Ly has deliberately borrowed the title of his film from Hugo’s famous work. As Tom Pointon writes ‘Ladj Ly boldly inserts himself into a canon of French auteurs and ensures the posterity of this audacious debut’.59 Claiming lineage from Hugo, and placing the film in dialogue with a canonical text, lends importance to the banlieue film and elevates it above a niche and arguably stereotyped genre.

The first mention of Hugo in the film is when Chris asks Stéphane if he knows why the local high school is called ‘Victor Hugo’. It is so called because the Thénardiers’ Inn in Hugo’s Les Misérables was in the outlying Montfermeil and this is where the hero, Jean Valjean, meets the orphan Cosette. The corrupt Thénardiers cheat their customers and abuse Cosette when she is placed in their care. Chris is surprised that Stéphane should know about Hugo, jokingly asking him whether he has read the book and accusing him of being an ‘intello’. Stéphane denies having read it, saying he had just looked at the website for the town. Hugo is identified as highbrow culture and the police squad are anxious to distance themselves from any suggestion that they might have read the book.

Nevertheless, the protagonists of the film could be seen as contemporary counterparts of the novel. As Stéphane remarks ‘ça n’a pas beaucoup changé’ [it has not changed much]. For Mark Kermode, ‘The ghosts of Victor Hugo’s downtrodden 19th-century rebels haunt Ladj Ly’s César-winning contemporary urban drama, a streetwise tale of France’s dispossessed masses, brought once again to the brink of rebellion’.60 Sébastien Le Pajolec and Jean-Jacques Yvorel trace the evolution of the archetype of the gamin de Paris [street urchin] from the prototype of the boy with the pistols in Delacroix’s La Liberté guidant le people as the ancestor of Hugo’s Gavroches to ‘les “jeunes des cités” [qui] constituent l’ultime version du stéréotype d’une jeunesse dangéreuse dans les imaginaires parisiens’ [the youths of the high-rise estates [who] conform to the ultimate stereotype of a dangerous youth population in minds of Parisians].61 But whereas the ‘gamin de Paris’ embodies the liberty and heroism of the ‘Trois glorieuses’ [July Revolution] and the overthrow of Charles X in 1830, the ‘zonards’ [dropouts] contribute to ‘une légende noire’62 [shadowy legend] of the male delinquent in a tracksuit and baseball cap.63 As we will see, Buzz is Gavroche, Hugo’s spokesperson for the destitute: ‘Victor Hugo va créer un personnage là où il n’existait qu’un être collectif. Et ce personnage présente une particularité décisive: il est la voix des misérables’ [Victor Hugo creates a character where previously there was only a collective being. And this character has a distinguishing feature: he is the voice of the destitute].64

In Ly’s film, which highlights how those in the cité are trapped like animals in a cage, like the lion cub that Issa steals from the circus, the prospect of redemption and reform sought by Jean Valjean in Hugo’s novel is treated with suspicion, both by the police and by other residents. Chris meets a man that he had put in prison who is now neatly dressed in a suit and looking for work as a gardener in the concrete jungle. After he has left, Chris informs the newcomer, Stéphane, that he was ‘one of his best clients’ and that he will give him six months before he reoffends. Salah is another reformed character who now owns a kebab restaurant and commands a certain amount of respect as a peaceful community leader. Rivals for his authority are quick to remind him, however, that they know his past and threaten to use it against him. Similarly, the young Issa is seen as only capable of getting into trouble and he spends the night sleeping amidst the refuse on the estate after his father disowns him and refuses to allow him home. Indeed, the images of entrapment are everywhere; however, the terrifying roar of the lion during the circus sequence suggests a latent power of revolt.

Hugo’s text is a tale of revolt and references to the text inspire and bookend the film. As well as giving the film its title, setting, themes and, loosely, its characters, the film ends with Hugo’s maxim: ‘Mes amis, retenez ceci, il n’y a ni mauvaises herbes ni mauvais hommes. Il n’y a que de mauvais cultivateurs’ [Remember this, my friends: there are no such things as bad plants or bad men. There are only bad cultivators]. If as a genre, the banlieue film focuses on young people and their lack of prospects, Les Misérables emphasizes the important role of ‘cultivators’, or educators. Ly made a deliberate choice to set the film during the summer when school is out. As such, it avoids one of the commonplaces of banlieue films which is the ‘situation d’échec scolaire’, or poor performance at school, that is typical of many children from disadvantaged backgrounds. Such is the focus for example in Laurent Cantet’s 2008 film Entre les murs [The Class], based on François Bégaudeau’s novel of the same title and starring the writer himself as a white teacher in a ‘difficult’ school.65

Although school is deliberately avoided, the figure of the educator or role model is forwarded in the film. We first meet Issa’s father at the police station. The father is causing a disturbance, shouting at Issa and throwing things at him because the boy has been caught stealing. Issa says nothing and just cowers in a corner. Chris proves another poor role model. After abusing his position of authority and threatening a female minor with an intimate body search during an identity check at the bus stop, he tries to reaffirm his position and legitimize his actions by reminding her that she should not smoke because it is bad for her health.

Ly challenges another mainstay of the cinematic representations of the banlieue by not focusing on a so-called ‘Integrationist’ threat to society. Salah is shown to be peaceful; it is Chris who fabricates his Sala(h)fist links – showing not the usual fertile ground for radicalization, but rather a space of projection for fears of terrorism. The ‘Frères mus’ [Muslim Brothers] are shown in a good light. They have cleaned up the drug problem in the area. They try to talk to the youth and explain the importance of behaving well towards other people. They invite them for refreshments and a talk at the Mosque. The film thus refuses to create an intrinsic link between religiosity and radicalization.

The three girls who confront Buzz about spying on them with his drone are also shown to be good educators. The dominance of the male gaze is challenged when the girls ‘repurpose’ the drone. Rather than subscribing to a patriarchal worldview and seeking justice in punishment and revenge, the girls offer Buzz the chance to channel his talents into giving something positive back to the community. They invite him to film their basketball game, instead of spying on them uninvited and violating the intimate space of their bedrooms by peering in through the window. Rather than being punished, Buzz will atone by doing something for the girls that they will appreciate and which will be rewarding and valorizing for him too (though the opportunity is lost as the police break his drone).

Salah too functions as an educator. It is to Salah that Buzz turns when he is chased by the police. In the film, however, it is Stéphane, the new police recruit, who receives a lesson from him. Salah commands our attention. He distinguishes himself from the other male characters by his calm and majestic presence. When Stéphane asks him whether he might have any information about the theft of the stolen lion cub, Salah replies instead with proverbial wisdom.

‘Crois-tu que le cirque soit la place d’un lion? Dans l’Islam, le lion est un animal majestueux qui incarne force et grandeur. Les hommes ne devraient pas mettre en cage un animal aussi sage. […] L’homme crée des contraintes là où il ne devrait pas en exister; cela s’appelle la servitude’.

[Do you think a lion belongs in a circus? In Islam, the lion is a majestic animal that embodies force and power. Man shouldn’t cage such a wise animal. […] Man creates unnatural constraints where there shouldn’t be any. That’s called servitude.]

Salah’s speech and the references to ‘caged animals’ is a reminder of the dehumanizing colonial phenomenon of the human zoo where supposedly ‘primitive’ people were publicly exhibited. In contrast to Stéphane, who is anxious and awkward, Salah is eloquent and speaks like a conteur [storyteller]. His words are also a reminder of the oral tradition in Africa and give testimony to the ignominy of entrapping the banlieue population in dependency and degrading poverty.

If the lion is an extended metaphor in the film for freedom, then the chicken is also an extended metaphor. When Issa throws the live chicken into the room with the lion cub, we understand why he stole the chickens. The cockerel is the symbol of France and of the values of the Republic and has been ‘emasculated’ and sacrificed to the lion. Les Misérables is reworked and the fable could have been called ‘The Lion and the Cockerel’. The proud strutting cockerel with the recent values that the French Republic has bestowed on it will be no match for the lion. If Chris is the cockerel, Issa is the lion cub. When Salah hands over the memory card for the drone, he gives a prescient warning: ‘Et s’ils avaient raison d’exprimer leur colère. […] Vous n’éviterez pas leur colère et leurs cris’ [What if they were right to voice their anger […] You won’t avoid their anger and their cries]. As Richard Brody writes, ‘[The film is] a display, for the edification of white French people, of the abuses in which they’re obliviously complicit and the righteous anger that they arouse unawares’.66 Salah’s fable of the lion is a lesson about righting the wrongs done to the oppressed.

The film also counters some of the negative imagery of the banlieue with positive imagery, most notably though the Tontine, in which members of the community club together to form an unofficial lending bank to finance a large project like a marriage or a trip abroad. This happens behind closed doors in the intimate domestic space of Issa’s apartment and we only discover it when Gwada is permitted to search the premises. The toxic masculinity which characterized benchmark banlieue films such as La Haine is largely avoided in Ly’s portrayal (or rather it is transferred onto Chris and the police). The female characters are less present in the film, but where they are present, they are presented in a sympathetic light, offering respite and an alternative space, as in the scene in which a mother defends her children from habitual police harassment. Such solidarity between community members, both male and female, is the less visible aspect of the banlieue communities and is represented here as a positive female support network. This runs counter to Westling’s belief that in terms of the representation of women there has been little progress since La Haine: ‘to the extent that family relations with mothers, sisters and girlfriends are practically non-existent in both films’, although the films mentioned above go further in foregrounding women.67 Undeniably, there is a continued masculine bias in the film with women very much in the background and only playing supporting roles.

Furthermore, whereas in Hugo’s Les Misérables, the destitute were fictional characters in a tale written by someone else, the advent of cinema and of more widely accessible means of production and platforms for distribution has meant that both actors and the members of the general population from underprivileged backgrounds can figure in their own stories. The film includes several mise-en-abyme uses of a camera to record footage of police misconduct, advocating active digital participation in the construction of meaning. When Chris conducts the abusive body search of the girls at the bus stop, they defend their rights and one of them films the abuse. Chris smashes the phone in a typical act of police violence, but Ly advocates the use of an otherwise effective means of self-defence, as will be seen.

Girls film inappropriate police search. Les Misérables, dir. by Ladj Ly (France, 2019), 20:09. Reproduced with permission of SRAB Films - Rectangle Productions - Lyly Films.

Chris is out of line, a law unto himself, even declaring that ‘C’est moi la loi’ [I am the law]. As such, he is the embodiment of the French state. When Gwada claims that the police are respected in the cité, Stéphane points out that it is not respect that they inspire but fear. The police abuse their power: we see Chris carry out the inappropriate body search; he resorts to bribery; he enlists the help of the local drug dealer, ‘La Pince’, in return for turning a blind eye to his business. When Salah refuses to help him recover the drone’s memory card, he tries to intimidate him with the threat of placing him on the Fiche S watchlist as a terrorist threat to national security. Chris’s lack of respect for the youth on the estate is clearly indicated by the fact that he refers to them as ‘microbes’, recalling the former President Nicolas Sarkozy’s use of the word ‘racaille’ or ‘scum’ on several occasions to describe certain inhabitants of the banlieue. His choice of vocabulary was a contributing factor to the 2005 unrest.68

Beyond literature and film, what the widespread use of camera phones offers is accountability. The police cannot act with impunity. As Leigh notes:

using camera phones to record encounters with the police would [become] common practice worldwide. In the early 2000s, Ly became an accidental pioneer – police harassment was so rife in Les Bosquets, he says, that he kept running into it. He soon noticed that his presence – or that of his camera – made officers newly observant of protocol. Soon, local residents called for Ly whenever police cars appeared.69

The incident when the police flashball Issa is filmed by Buzz, a child with a drone. Buzz’s English name is significant, signalling a desire to ‘cause a buzz’, to make a noise with his drone and bring the plight of the banlieues to international attention. Flashball guns are illegal in most European countries. In France they have been used against urban rioters since 1995. They were used notably in the 2005 riots. Civil rights groups seek to have them banned. Mustapha Ziani died of a heart attack after being flashballed in the chest by the police in Marseille in 2010. The officer was eventually given a six-month suspended sentence for manslaughter.70 Ly reverses the usual media stereotypes when Salah, who is threatened with the charge of terrorism, points out that the police are entrusted with arms and misuse them.

Buzz captures police brutality on camera using a drone. Les Misérables, dir. by Ladj Ly (France, 2019), 20:40. Reproduced with permission of SRAB Films - Rectangle Productions - Lyly Films.

Yet Tarr argues that one of the defining features of the genre is that the trapped protagonists ‘are also shown as on the move, momentarily escaping surveillance by transgressing orders and finding new spaces to appropriate’.71 Buzz (Gavroche), transgresses the confines of his everyday world, picking the lock with his screwdriver and appropriating the freedom of the rooftops and the God-like perspective they offer on the city. Like the police in their surveillance vehicle, however, he has to learn not to abuse that power in perverse practices of voyeurism as he spies on girls in the intimate space of their bedrooms. Al-Hassan Ly, who acts the part of Buzz, is actually Ly’s own son and as such represents the next generation of activists. Westling argues that the focus of the film is on intergenerational justice. She applies Nicholas Mirzoeff’s theory of countervisuality to the film (the right to look (back) and to dismantle visual strategies that reinforce hegemonic power) and argues that ‘Ly claims the children’s “right to look” and to demand a better society’.72 The film turns surveillance on its head: momentarily escaping Racière’s culture of police surveillance, instead the youth watch the police, from the rooftops with the drone and through the spyhole onto the stairway, using their phones to capture police activity on camera as Buzz does.

‘Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat’ says Chris, waiting for the lion cub thief to incriminate him/herself online, which Issa indeed does with a picture of himself holding the cub: the new generation of activists still need to learn how to use new technologies to empower themselves. In Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century, Henry Jenkins argues that, in addition to teaching traditional core literacy of print media, the new media literacies should be taught and ‘seen as social skills, as ways of interacting within a larger community, and not simply as individualized skills to be used for personal expression’.73 Digital activism can be a way of gaining leverage, as the police fear in the film, but it also has its dangers and might be used as a form of voyeurism, cyber bullying or trolling.74 The film shows a glimpse of possible abuses, from Buzz’s voyeurism to potential cyber bullying as the girls request a copy of one of the clips that he has taken. More importantly though, with the filming of police violence on two occasions (the search and the shooting) we see the potential for such footage to circulate on social media and for digital activism to set the public agenda, hold those in public office to account and campaign for change. If used in an ethical way as an instrument of social change, digital activism can be a force for good. In analysing the new tools and possibilities available to digital activism, from setting up websites to blogging to posting photographs that will go viral, Anastasia Kavada argues that one of its main functions is to bypass the mainstream media.75 We do not see the children in school, but in an extension of print literacy, the film highlights the benefits of literacy in the new online media and of digital activism as an empowering tool and one which can overcome the usual stereotyping and discrimination.

Conclusion

The concerns of the film are neatly summed up in the images of the children playing in the rubbish. The banlieue film is a genre which focuses on adolescence and one of the first things that shocks us as spectators is that the children are happily playing in the trash. They have reappropriated their environment, improvising sledges out of discarded items and sliding down the concrete slopes of the ‘pit’ into a pile of rubbish which sends the dust and dirt flying. When Issa is shot, he falls into a pile of rubbish. When his father turns him out, he spends the night sleeping in a makeshift bed constructed out of an armchair and amidst other larger items of furniture which litter the estate. The suggestion is that society treats these children as trash, judging them and casting them off without giving them a chance and consigning them to the social dustbin of the banlieue.

We do not see the children at school; Ly refuses to typecast the children from ‘problem’ estates as underperforming at school. Nevertheless, the film is framed through the quotation from Hugo on the importance of upbringing. In taking an unflinching look at the banlieue, Ly’s social cinema tries to educate the viewer. With its open freeze frame ending on Issa about to throw the incendiary device, the film invites our participation in thinking about what will happen next and consideration of both violent and non-violent means of protest.76 The film responds to the challenge of how to make literature relevant today. Literary works should not be restricted to the context of their times but can also be used to explore their resonance with the present moment. Texts are not closed, but rather open dialogues which can speak to the present.

The film challenges the claim of the Republic to universal values, showing instead, as Hugo’s novel does, the marginal and the excluded. If in Hugo’s time, as now, there were barriers to education and literacy, the new media of the twentieth and twenty-first century provide more widespread and participatory access. Phones have become cheaper and more powerful, able to replicate the functions of a computer, which has enabled more widespread access. Like the drone, the film is a probe which opens up the banlieue to new readings: if literature and education raise questions of accessibility, digital activism is seen as an empowering tool, giving leverage in the fight for social justice. Rather than relying on famous mainstream white writers to champion their cause, new media in the twenty-first century offer people agency and the chance to move forwards and participate themselves in accurately portraying their world, fighting their cause, and creating their own narrative.

Notes

Tim Arango, Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs and Jay Senter, ‘Three Former Officers Convicted of Violating George Floyd’s Rights’, The New York Times, 24 February 2022, <https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/24/us/guilty-verdict-george-floyds-rights.html?msclkid=6cd3e162c4d611ec961e0c15bf5fd044> [accessed 28 April 2022].

Danny Leigh, ‘Les Misérables: Scenes From Banlieues of Paris’, The Financial Times, 20 August 2020, <https://www.ft.com/content/26bf39e0-1b67-4e92-8167-056c64d8ff44?msclkid=0bd56c9ac66b11ecb46f0bf7122de670> [accessed 28 April 2022].

Iman Amrani and Angelique Chrisafis, ‘Adama Traoré’s Death in Police Custody Casts Long Shadow over French Society’, The Guardian, 17 February 2017, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/17/adama-traore-death-in-police-custody-casts-long-shadow-over-french-society?msclkid=83e1f1e1c4d711ec9053ff1fcd3b5187> [accessed 28 April 2022].

Afua Hirsch asks ‘Is there any point talking about race when class is the major basis of resource distribution in society?’. ‘Yes,’ she replies, ‘because race and class intersect and those disadvantaged by both face unique challenges, because there is a specific baggage attached to race that is a very real factor shaping all of our lives’; Afua Hirsch, Brit(ish): On Race, Identity and Belonging (London: Jonathan Cape, 2018), p. 24. Paul Gilroy argues that the two are distinct: ‘The processes of “race” and class formation are not identical. The former is not reducible to the latter even where they become mutually entangled’; Paul Gilroy, There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation (London: Hutchinson, 1987), p. 38.

Karolina Westling, ‘Intergenerational Injustice in a Parisian Banlieue. Ladj Ly’s Contemporary Reframing of Les Misérables’, French Screen Studies, 2022, 1–16 (p. 4).

Westling, ‘Intergenerational Injustice’, p. 4.

Ginette Vincendeau, La Haine (London: I. B. Tauris, 2005).

Alec Hargreaves, ‘Black-Blanc-Beur: Multi-Coloured Paris’, Journal of Romance Studies, 5.3 (2005), 91–100 (p. 91).

All translations from French to English are my own, unless otherwise stated.

Jayson Harsin, ‘Cultural Racist Frames in TF1’s French Banlieue Riots Coverage’, French Politics, Culture & Society, 33.3 (2015), 47–73.

Laurent Dubreuil, ‘Notes Towards a Poetics of Banlieue’, Parallax, 18.3 (2012), 98–109 (p. 101).

Ibid., p. 107.

Ibid., p. 109.

Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (London: Routledge, 2010), p. xxv and passim. Bourdieu contrasts the term to ‘class culture’. The term ‘culture of proximity’ is taken from recent pedagogical developments in the field of education. See, for example, M. Martin Guiney, ‘How (Not) to Teach French: Psittacisme and Culture de Proximité in Three Cinematic Representations of School’, The French Review, 86.6 (2013), 1147–59.

Geoff Hare, Football in France: A Cultural History (Oxford: Berg, 2003), p. 135.

Patrick Mignon, ‘Le Francais Feel-Good Factor’ in Hooligan Wars: Causes and Effects of Football Violence, ed. by Mark Perryman (Edinburgh: Mainstream, 2001), pp. 165–78 (p. 168).

For a discussion of race and football see Christos Kassimeris, ‘Black, Blanc and Beur: French Football’s “Foreign Legion” ’, Journal of Intercultural Studies, 32.1 (2011), 15–29.

Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, trans. by Hélène Iswolsky (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984).

Marc Perelman, Barbaric Sport: A Global Plague (London: Verso, 2012). See also Stuart Jeffries, ‘Ladj Ly on Shocking President Macron with His Paris Riot Film: “How could he not know”?’, The Guardian, 20 August 2020, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/aug/20/ladj-ly-shocking-president-macron-paris-riot-film-les-miserables-la-haine?msclkid=deb09ba4c53711ec8d3230afe4aa509e> [accessed 28 April 2022].

Carrie Tarr, Reframing Difference: Beur and Banlieue Filmmaking in France (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005), p. 1.

Mustafa Dikeç, Badlands of the Republic: Space, Politics and Urban Policy (Oxford: Blackwell, 2007), p. 4.

Ibid., p. 8. See also Alec G. Hargreaves, ‘A Deviant Construction: The French Media and the “Banlieues” ’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 22.4 (1996), 607–18 (p. 607).

Julia Dobson, ‘Dis-Locations: Mapping the Banlieue’, in Filmurbia: Screening the Suburbs, ed. by David Forrest, Graeme Harper and Jonathan Rayner (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), pp. 29–48 (p. 30).

See for example comments by Fernand Ottin Pecchio and Bernard Zehrfuss on the ‘Cité des Bosquets’: ‘Malheureusement, suite à l’abandon du projet de l’autoroute A87, destinée à relier le plateau de Clichy-Montfermeil aux principaux pôles d’emploi de la banlieue parisienne (Roissy et Marne-la-Vallée en l’occurrence), et également à l’éloignement des transports et équipements publics, la cité des Bosquets s’est vite retrouvée coupée du monde’ [Unfortunately, following the abandonment of the A87 motorway project which was intended to link the Clichy-Montfermeil plateau to the job market of the Parisian suburbs (Roissy and Marne-la-Vallée in this case), and without public transport or amenities, the Cité des Bosquets quickly found itself cut off from the rest of the world]. PSS-ARCHI-EU website, 9 June 2019, <https://www.pss-archi.eu/immeubles/FR-93047-44738.html?msclkid=7d3d6fdec25211ecac42dd75e6f010f3> [accessed 28 April 2022].

See, for example, Stephen Jessel, ‘Jacques Chirac, Obituary’, The Guardian, 26 September 2019, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/sep/26/jacques-chirac-obituary> [accessed 28 April 2022].

Vincendeau, La Haine, p. 22.

Ibid., p. 22.

Dobson, ‘Dis-Locations’, p. 35.

Mehdi Belhaj Kacem, La Psychose française: les banlieues, le ban de la République (Paris: Gallimard, 2006), p. 63.

Ibid., pp. 40–41.

Ibid., p. 45.

Jacques Rancière, Disagreement, trans. by Julie Rose (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), p. 28.

Jonathan Ervine, Cinema and the Republic: Filming on the Margins in Contemporary France (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2013), p. 85.

Tarr, Reframing Difference, p. 2.

Ibid., p. 74.

Vincendeau, La Haine, p. 31. For further discussion of ‘off-whiteness’ in La Haine, see also Yosefa Loshitzky, ‘The Post-Holocaust Jew in the Age of Postcolonialism: La Haine Revisited’, Studies in French Cinema, 5 (2005), 137–47 and Sven-Erik Rose, ‘Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine and the Ambivalence of French-Jewish Identity’, French Studies, 61.4 (2007), 476–91.

Jeffries, ‘Ladj Ly on Shocking President Macron’.

Ginette Vincendeau, ‘The Parisian Banlieue on Screen: So Close, Yet So Far’, in Paris in the Cinema: Beyond the Flâneur, ed. by Alastair Phillips and Ginette Vincendeau (London: British Film Institute, 2018), pp. 87–99 (p. 87).

Vincendeau, ‘The Parisian Banlieue’, p. 89.

David-Alexandre Wagner, De la banlieue stigmatisée à la cité démystifiée (Bern: Peter Lang, 2011).

The term ‘Beur’, verlan for ‘Arabe’, is now outdated and considered as pejorative by some.

Will Higbee, Post-Beur Cinema: North African Émigré and Maghrebi-French Filmmaking in France since 2000 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2022), p. 183.

Ibid., p. 183.

Ibid., p. 187.

Ibid., p. 188.

Elena Lazic, ‘Ladj Ly on Les Misérables: “Film is a tool. It changes things” ’, Sight and Sound, September 2020, <https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/interviews/ladj-ly-les-miserables-film-tool-change?msclkid=0676ded0c33411ecb29ad34375616806> [accessed 28 April 2022].

Leigh, ‘Les Misérables’.

Dobson, ‘Dis-Locations’, p. 35.

Vincendeau, La Haine p. 84.

Jeffries, ‘Ladj Ly on Shocking President Macron’.

François-Xavier Rigaud, ‘Montfermeil: le dernier adieu de JR et Ladj Ly à la cité des Bosquets’, Le Parisien, 15 August 2020, <https://www.leparisien.fr/seine-saint-denis-93/montfermeil-le-dernier-adieu-de-jr-et-ladj-ly-a-la-cite-des-bosquets-15-08-2020-8368257.php> [accessed 28 April 2022].

Johny Pitts, Afropean: Notes from Black Europe (London: Allen Lane, 2019), pp. 25–26.

Tarr, Reframing Difference, p. 3.

Rogers Brubaker and Frederick Cooper, ‘Beyond “Identity” ’, Theory and Society, 29.1 (2000), 1–47 (p. 20).

Ibid., p. 11.

John P. Murphy, Yearning to Labor: Youth, Unemployment, and Social Destiny in Urban France, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2017), p. 113.

Brubaker and Cooper, ‘Beyond “Identity”’, p. 11.

Dobson, ‘Dis-Locations’, p. 34.

Tom Pointon, ‘Film Review: Les Misérables’, Afropean: Adventures in Black Europe, January 2020, <https://afropean.com/film-review-les-miserables/?msclkid=c8d045d4c73611ec81c1addf7e286276> [accessed 28 April 2022].

Mark Kermode, ‘Les Misérables review – a Simmering Tale of Two Cities’, The Guardian, 6 September 2020, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/sep/06/les-miserables-review-ladj-ly-paris-riot-film-cesar> [accessed 28 April 2022].

Sébastien Le Pajolec and Jean-Jacques Yvorel, ‘Du “gamin de Paris” aux “jeunes de banlieue”: évolutions d’un stéréotype’, in Imaginaires urbains du Paris romantique à nos jour, ed. by Myriam Tsikounas (Paris: Editions Le Manuscrit, 2011), pp. 210–46 (p. 239).

Ibid., p. 191.

Ibid., p. 239.

Ibid., p. 193.

See for example Abdoulaye Gueye, ‘The Color of Unworthiness: Understanding Blacks in France and the French Visual Media through Laurent Cantet’s The Class’, Transition, 102 (2009), 158–71 or James S. Williams, ‘Framing Exclusion: The Politics of Space in Laurent Cantet’s Entre les murs’, French Studies: A Quarterly Review, 65.1 (2011), 61–73. Other films include Mehdi Idir’s La Vie scolaire (2019).

Richard Brody, ‘The Urgent but Stilted Les Misérables’, The New Yorker, 22 January 2020, <https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-front-row/the-urgent-but-stilted-les-miserables?msclkid=427a7a5ac6c811eca36d1345884b8262> [accessed 28 April 2022].

Westling, ‘Intergenerational Injustice’, p. 2.

Le Monde avec AFP, ‘Nicolas Sarkozy continue de vilipender “racailles et voyous” ’, Le Monde, 11 November 2005, <https://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2005/11/11/nicolas-sarkozy-persiste-et-signe-contre-les-racailles_709112_3224.html?msclkid=4789f9fdc5f911ec8128668528bd12e0> [accessed 28 April 2022].

Leigh, ‘Les Misérables’.

Stéphanie Harounyan, ‘Bavure à Marseille, le procès du premier mort du flash-ball’, Libération, 27 January 2017, <https://www.liberation.fr/france/2017/01/27/a-marseille-le-proces-du-premier-mort-du-flash-ball_1544530/> [accessed 28 April 2022].

Tarr, Reframing Difference, p. 20.

Westling, ‘Intergenerational Injustice’, p. 1.

Henry Jenkins, Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009), p. 32.

See for example Steven Murdoch on new forms of harassment, ‘Destructive Activism: The Double-Edged Sword of Digital Tactics’, in Digital Activism Decoded: The New Mechanics of Change, ed. by Mary Joyce (New York: International Debate Education Association, 2010), pp. 137–48.

Anastasia Kavada, ‘Activism Transforms Digital: The Social Movement Perspective’, in Digital Activism Decoded, pp. 101–18 (p. 106).

Recalling the ending of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989).