-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Catherine Emerson, Digital Prompts and Narrative Cues: Storytelling in the 1450s and in the 2020s, Forum for Modern Language Studies, Volume 59, Issue 4, October 2023, Pages 530–544, https://doi.org/10.1093/fmls/cqad042

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

The Cent Nouvelles nouvelles present challenges to student learners of French linguistically, culturally and in terms of the content of the stories. Investigations designed to interrogate how the stories might have been collected in the second half of the fifteenth century end up demonstrating how the storytelling environment shapes the stories that are told and the way that they are understood. The experience of storytelling online during a period of pandemic learning is very different from the same experience in a pre- or post-pandemic classroom. Methodologies, such as critical pedagogy and inquiry stance pedagogy, which had limited resonance in the pre-pandemic environment, became much more central to the learner’s experience in the online, pandemic environment. This confirms the practices of ‘Flux pedagogy’, as advocated by Sharon M. Ravitch. Similarly, reactions to a story featuring the transmission of plague can be shaped by a framing that includes or excludes direct reference to the risk of infection experienced by the listeners.

The challenge of the ‘Cent Nouvelles nouvelles’

What follows is a reflection on how storytelling – and the understanding of stories – is shaped by the environment in which those stories are told and heard. The impact of the reading environment on reader response and interpretation has long been recognized.1 Recently, attempts have been made to quantify this effect using the big data available from online reviews and particularly the re-narration of plots produced in these fora.2 In the present study, readers’ reactions to their environment are examined through the prism of the stories that they tell in response to other stories encountered in a challenging corpus. These reactions were also observed in responses to questionnaires designed to interrogate the link between the corpus and the environment. This meditation focuses on the experience of three consecutive cohorts of readers – students – encountering challenging literature in challenging times. Some of the approaches described here correspond to those advocated by Sharon M. Ravitch in her description of ‘Flux pedagogy’ – a humanizing educational approach which is trauma-informed, student-centred and critical, and which promotes inquiry as stance, racial literacy and brave space pedagogy.3 The practical engagement enacted through the process of storytelling allowed learners to grapple with questions of composition in a remote era and to relate to each other in a mutually supportive ‘brave space’.4 Through interrogating the various ways that literature challenges us, the readers were also able to shed light on how stories may have been composed and understood in a remote era. Reflecting on what is challenging about the process of storytelling, and developing strategies to overcome these barriers illuminates the processes at work in narration and reception.

The core text, which was the subject of the course studied by the students and the starting point of their own narrative efforts, is the Burgundian Cent Nouvelles nouvelles [One Hundred New Tales], a collection composed or compiled in the central years of the fifteenth century.5 In many senses, it is a difficult text: the circumstances of the work’s composition appear to have been complex since it is an anonymous collection where individual tales are nevertheless attributed to different narrators, most of whom have a verifiable and documented historical existence. The exclusively male society implied by the names of the narrators, and the frequently sexual and scatological content of the tales themselves, can also make the collection challenging. At times the impression that the collection gives is that the reader has walked in on an intimate circle telling stories that are meaningful only to themselves, and, indeed, this is how the text has been imagined by some critics.6 At the same time, brevity, humour and accessibility characterize the stories, making them easy to understand and, crucially, easy to tell. Many of the tales are reused from earlier sources, and many focus solely on the central relationships between characters, meaning that the stories, stripped of contextualizing detail, are timeless.7

If the stories are challenging because of their subject matter and of the remoteness of their context, they are also challenging to teach because the language used – Middle French – is distant from that used by any contemporary students, whether francophone or otherwise, and is especially distant from the standardized Modern French taught as a foreign language. Culturally too, although the tales are in a sense timeless, they come wrapped in the context of the court of Philippe le Bon (1396–1467) and of the artistic culture of Burgundy at the time. Narrative commonplaces, such as the lascivious nature attributed to clerics – and especially to friars – no longer have the same cultural relevance, with student readers tending to assume that they represent a documentary commentary on the actual nature of churchmen, rather than a complex mix of mimesis and narrative conventions. Rather than enjoy topoi recycled from earlier story forms such as fabliaux, as the fifteenth-century audience would have been able to do, modern students need to be informed as to the origins of the tales they are studying.8

Narrative prompts and narrative framing

Three successive cohorts of students form the focus of this study. In each case, they engaged with and investigated the narrative dynamics of the text in a practical experience of storytelling in very different environments, in person and online, but also with different shared experiences which shaped both how they told stories and how they understood them. The students in three consecutive years of a final-year undergraduate course in an Irish university in March 2020, March 2021 and March 2022 developed different narrative strategies as demonstrated by the way in which they used prompts to produce a chain of stories that mimicked those of the Cent Nouvelles nouvelles in certain aspects. At the same time, their engagement with the text itself appears to have been affected by different environmental factors surrounding their storytelling. In the latest of these three iterations, the students and other listeners participated in a series of retellings of the same story (tale 55 of the collection) in order better to interrogate how reactions to challenging subject matter are shaped by context. Reactions to different storytelling contexts were explored through translation exercises, surveys and role-play in a succession of stagings of the tale that manipulated variables relating to the tale’s context and invited the audience to supply a personal reaction to the content.

The importance of the narrative prompt in storytelling, including in earlier texts such as the Cent Nouvelles nouvelles, has been noted. Although the frame narrative that brings together different purported storytellers is often considered to be a pretext for the juxtaposition of ‘otherwise unrelated stories’, it is also a structuring device that allows the author to use metanarrative processes to point to larger conclusions about the human condition than can be represented in a single story.9 Beyond this, frame narratives that set problems or announce themes have parallels in the lived praxis of storytellers, adding credibility to a collection’s pretensions to authenticity in its presentation of oral storytelling.10 A particularly elaborated use of the framing narrative, incorporating narrative prompts, is found in Boccaccio’s Decameron, in which ten named characters each tell a story over ten days of a two-week quarantine and exile from a plague in Florence.11 Stories each day are grouped under themes such as love affairs that end unhappily (day four) or happily (day five), and these themes can be read both as a structuring device for Boccaccio to present his collection of tales and as narrative prompts for his characters, who respond to the task set and comment upon it.

No such prompting is apparent in the Burgundian collection, where the frame narrative is implied by the names of the narrators at the beginning of each story (they were all prominent men in the court of Duke Philippe le Bon, most of whom were associated with the Duke’s bedchamber).12 Nevertheless, the collection presents itself as a conscious imitation of Boccaccio’s work: a prologue addressed to Duke Philippe says that the work ‘en soy contient et tracte cent histoires assez semblables en matere, sans attaindre le subtil et tresorné langage du livre de Cent Nouvelles’ [‘It contains and treats one hundred stories, of rather similar material, but it does not attain the subtle and very ornate language of the One Hundred Tales’].13 This notwithstanding, the collection is not divided into sections in the way that the Decameron is, and there is no overt sign of narrative prompts, although chains of stories which develop similar themes can be identified and the cast of narrators changes in the course of the work, as one might expect were the collection to be based on a storytelling event that took place over a number of distinct occasions. An example of such narrative sequences can be seen in the progression from tale 79 to tale 80, both of which feature donkeys: the first as a straying domestic animal and the second as an unflattering sexual comparator for a young husband. In the tale that follows, tale 81, the presumed narrator, Monsieur de Wavrin, comments on this sequence, saying ‘Puis que les comptes et histoires des asnes sont acevez, je vous feray en bref et a la verité ung bien gracieux compte d’un chevalier que la plus part de vous, mes bons seigneurs, congnoissez de pieça’ (Nouvelles, 473) [‘Since the donkey tales are finished now, I will compose a story which is brief, true, and very charming, about a knight whom most of you, my good lords, already know’ (Tales, 286)].

Studying by doing in a pandemic

Comments such as the one quoted above suggest a genuine event at which stories were told, and a real storytelling public, who also formed the audience for the tales and were intimately associated with each other. This leads us into one of the most hotly-debated questions in scholarship concerning the Cent Nouvelles nouvelles – namely whether it is the product of a genuine storytelling event or of a single controlling author counterfeiting such an event. Whilst the consensus amongst literary scholars is that the frame is a fiction that simply brings diverse stories together, readers who approach the collection from the angle of documentary studies and historiography find many connections between the narrators and the tales attributed to them.14 These connections, and the sequences of motifs which replicate features of oral storytelling, suggest that if it is a fiction constructed by a single author, it is a very realistic one.15 The undergraduate course upon which this study is based addresses these questions head on. In order to understand the mechanism whereby narrative chains arise, and thereby indirectly to throw some light on the question of how the collection was composed, a key hour that would normally be devoted to a lecture is given over to a session where students are invited to tell their stories. Starting from a position that presumes that a practitioner discovers more about a work of art by trying to recreate it than they would from simply studying the finished product, students are placed in groups and asked to spend the hour telling stories. This session is announced in advance: students do not have the request sprung upon them, a decision that brings its own challenges, with some students choosing to opt out of attendance rather than participate in an exercise in which they are expected to perform.

The session occurs nine weeks into the study of the work, with the result that the students are primed by the sort of material that has featured in previous weeks. Because the course is often the students’ first encounter with Middle French, this is a selection that tends to focus on the shorter, less complex tales, without some of the cultural specificity encountered in a very few stories in the collection, which might make them particularly resistant to interpretation.16 At the same time, stories which are particularly sexually frank are not used in the early part of this course. The decision to avoid stories of this nature is deliberate, given the challenge presented by the language and the vulnerability of students attempting to decode texts which are both culturally and linguistically strange. Students tend to oversexualize their interpretation of challenging lexical items, as when, in a previous course with similar linguistic material (though without overt sexual content) the word teste – ‘head’, with fifteenth-century spelling – was interpreted by a number of students as referring to a different part of the anatomy. Also, the focus of the current course is on narrative construction, the relationship between text and image and the uses of storytelling: questions that can be addressed without engaging with the sexual and scatological content of some of the tales. For this reason, stories containing graphic sexual content, such as tale 66, in which a child gives a description of his naked mother’s genital organs, are not taught.17 This said, students do have access to the whole collection and, in accordance with guidelines on teaching sensitive topics, they are informed of the sort of material that they may encounter and of the need to be respectful of each others’ sensitivities around these topics.18 Themes that do occur and are discussed in the early part of the course include infidelity and adultery, as well as murder in response to infidelity (tales 56 and 47 of the collection). These themes are treated by the narrator in a humorous tone, but it is acknowledged in class that these themes may be challenging to readers and that in some cases the humour of the narrative may actually render the content more disturbing.

Students who participate in the storytelling session are not obliged to tell stories of this nature, and indeed in most cases they do not do so, but it must be recognized that this is the context in which they embark on the enterprise of storytelling. It should also be acknowledged that, prior to the period examined in this article, this lecture hour was much less well attended than other sessions in the course. These sessions take the form of either translation classes (for the first six weeks of the course, while the students are becoming used to Middle French) or of conventional lectures (in weeks 7 and 8 and in weeks 10 to 12). Student feedback in 2018 and 2019 suggested that the storytelling session in week 9 was the element of the course which students found most unsettling, and that many students consciously avoided a class in which they knew they were going to have to contribute material that they themselves supplied. On the other hand, it was the element of the course that garnered the most positive comments from students who did participate in it. Students who took part in the session (about a third of the class as a whole in each of the five years from 2018 to 2022), were more likely to understand the structure of the work studied, more confident in commenting on the texts as a collection rather than as individual stories and more likely to express satisfaction with their experience of the course. This last question was evidenced by a direct question in student feedback forms at the end of the course about appreciation of the material taught and of its intellectual value, whereas the greater understanding of the collection can be seen in the decreased tendency among students in this population to express confusion or criticism of the text in their comments.19 It is therefore apparent that this particular session in the course was one that presented especial challenges to the student population, but was also one which yielded a particularly rich experience for those who did participate. This approach to understanding writing through praxis is an instance of inquiry stance pedagogy. It was an approach which students found unsettling but rewarding prior to the pandemic but which, as Ravitch hints, became particularly crucial during the period of pandemic restrictions and in particular that of online learning.20

The student population that encountered this session in 2020 was very different from that which performed the same exercise in 2021, and different again from the cohort that encountered it in 2022, largely because of the different restrictions placed on each group by the global pandemic. In 2020, the session took place on 11 March, which turned out to be the very day before the Irish government announced that universities would close and learning would thenceforth be remote. 13 March 2020 was the first day of an extended shutdown period, in which students and instructors learned new ways of interacting synchronously and asynchronously, and grappled with video conferencing. An additional consequence of the pandemic for students of languages was that restrictions on travel meant that students who would normally have been able to travel abroad as part of their studies were not able to do so. Final-year students in March 2020 thus differed from those of March 2022 in that those in the former group had overwhelmingly spent time in France, Belgium or another European country in the previous academic year, whereas those in their final year of study in 2022 had not. In the academic year 2020–2021, no travel abroad was sanctioned by the university, with students either completing the final year of their studies in Ireland with the option to proceed to a year abroad following this, or spending the year engaged in study of a non-language subject in Ireland if their programme allowed, before proceeding to a final year in French without having spent the period abroad that would normally be part of the curriculum. These circumstances resulted in a cohort in 2022 that was made up entirely of a smaller group of students on four-year programmes that did not necessarily involve a year abroad.

The intermediate cohort, in 2021, was much larger than that which followed, and somewhat larger than the previous cohort in 2020. Half these students had not gone abroad, as they were enrolled on a ‘flipped’ year, with their residence abroad delayed until travel restrictions permitted movement, while the other half had followed the conventional path with a third year abroad followed by a fourth year in Ireland exiting to the degree qualification. Those students in the 2021 cohort who had participated in an Erasmus exchange had returned precipitously in March 2020 at the onset of pandemic restrictions. A further difference between the three sessions was that the 2021 session, which took place on 24 March, was held online, towards the end of an academic year when no in-person teaching had occurred. The session in 2022 was held in person, with numerous visible reminders of the pandemic situation – most notably face coverings – apparent in the classroom. These three student groups, therefore, came to the session with very different life experiences, and this was reflected in the way that they approached the task of storytelling.

The most visible sign of this difference was that the classes in 2021 and 2022 did not experience the dramatic drop in attendance that had been observed in this equivalent session in previous years. It is true that attendance in this session in 2021 and 2022 was seventy to eighty per cent of attendance in the previous lecture, but this was in line with a drop in attendance in other classes seen in the cohort as the semester progressed and was not related to the content of the class. Moreover, in 2021 in particular, the students took conscious steps to mitigate the attrition in attendance when it came to this particular session, rearranging their schedules so that all students who were present attended in the first half of a two-hour online slot that had been provided to facilitate all timetables, and commenting that they had done this because they wanted to be in the same – larger – group. These students remarked during the session and in course questionnaires afterwards that they had limited opportunities for social interaction in their current situation and that they consequently welcomed this session. At the end of the first hour, a number of students stayed behind, ostensibly to see if others would join in the second hour and with the stated aim of ensuring that any such students had a sufficiently large audience for their stories. However, as the session continued and no new participants joined, it became apparent that students were prolonging their participation to benefit from the opportunity to tell fresh anecdotes. This pattern of attendance was facilitated by the flexibility allowed by a slot timetabled for online participation – an evening class where students would not have a lecture in the following hour – but also by the informality of a class where the facilitator and participants were attending from their homes.

These contextual differences impacted on the way that the sessions developed. In 2020, conversations were slow to start, and participants relied heavily on the prompt sheet provided by the lecturer facilitating the group. Storytelling did not occur organically from the outset, and participants created mechanisms to compensate for the absence of natural sequential organization between narratives.21 These mechanisms mainly revolved around the explicit codification of turn taking by, for instance, adopting a pattern in which tellership moved clockwise around the group, or through explicit return to the prompt sheet between narratives, often reading down the sheet and selecting the next topic or the next one that lent itself to storytelling. As the session developed, however, participants relied less on the prompt sheet and stories tended to follow each other without interruption, often on topics suggested by the sheet. The most successful topics amongst participants in 2020 were reminiscences about school and narrations of experiences that students had had whilst participating on Erasmus exchanges. Both groups of stories reflected shared experiences among the participant group, with the school stories including a number of documented urban legends of the FOAF (Friend of a Friend) type.22 One instance of this was a story about a student prank involving a cow that was brought upstairs by a group of school students unaware of the supposed fact that cows cannot walk downstairs. This tale has been documented in various settings, including the College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts, and an unnamed public school ‘in a bit of a rural town in Australia’.23 Indeed, so prevalent is this urban legend that the Encyclopaedia Britannica has an article refuting the claim that cows are physically limited in this way, and there are many videos online debunking the myth.24 Characteristically of tales of this type, and exactly like the YouTube video tutorial cited in the previous endnote, participants in the 2020 storytelling session set it in the nearest secondary school to the university where they were studying. Despite the way in which the session was better attended in subsequent years, it would be wrong to consider the 2020 iteration of the storytelling session as a failure. Groups were slow to establish a rhythm and relied heavily on the prompts provided at the outset of the session, but by the end of the class the session had developed into an event which allowed participants to access stories that are attested as part of the oral repertoire.

By contrast with the earlier group, students in the 2021 cohort did not have any difficulty in beginning their conversations. Prompts were supplied on a slide in the main online classroom, and students were encouraged to take a screenshot of the prompts before being sorted into breakout groups to begin their session. However, conversations started immediately when the breakout groups began, without reference to the prompts. Whilst some of the breakout groups adopted ground rules to regulate the conversation, participants described these rules as a way of ensuring equal access to the storytelling position, rather than as a mechanism to avoid silence, as had been reported by participants in 2020. The nature of the stories told was more diverse in this group, and more closely reflected the challenging nature of the tales studied in the Cent Nouvelles nouvelles. Themes of tales told in the session included sex, death and embarrassment, and suggested both a greater degree of intimacy amongst the students participating in 2021 and a deeper reflection on the content of the material studied. It might seem paradoxical that a student group who had not had the shared experience of travel abroad would feel more comfortable sharing stories on challenging subjects. However, the group was made up in almost equal proportions of two distinct populations: one which had completed the majority of their Erasmus exchange and had returned home in a hurry at the onset of the pandemic, often supporting each other in doing so; and one which had had its travel ambitions frustrated during the summer of 2020, as it became apparent that the pandemic would not end in time for them to travel. It may be, therefore, that the session participants had developed a high degree of comfort with each other in adversity, although other explanations for this difference are possible, including the timing of the online class later in the evening and the nature of online interactions where most students were in their home environment.

The online environment and digital prompts

It is clear that the online environment also independently shaped the storytelling in 2021. Rather than referring to the prompt sheet that was provided, students resorted to the online tools provided by the Virtual Learning Environment to generate prompts for storytelling, using chat, screen share and links to other media to tell their stories. Ravitch points out that a key element of successful Flux pedagogy is not trying to do the same thing online as in person, and the way that both facilitator and learners adapted the ways in which they engaged with this task show that this principle was instinctively understood by all participants.25 Indeed, at the end of the session, those participants who had stayed behind for the second hour suggested an addition to the prompts used to initiate storytelling, to incorporate the prompt ‘Are you on the internet and why?’ This suggestion arose out of something that had happened in the larger group in the previous hour, when some of the students who had spent time on exchange abroad had shared a video of a mutual friend who had been filmed and broadcast live in an impromptu decade of the rosary while visiting Lourdes for tourist purposes.26 Following this, the smaller group posted a number of links in the chat function of the virtual classroom and this was inevitably followed by a narrative glossing the circumstances in which a particular video or website had been produced, a viewing of the link in question and a discussion incorporating further narratives from the students attending. In this instance, the environment in which the stories were told became itself a prompt for storytelling. This probably reflects the novelty of the online environment even in March 2021, and it would have been interesting to see if this effect had persisted in the following year, had classes remained online.

However, the session in 2022 was once more a physical session and as a consequence shared some of the characteristics of that in 2020. Like the earlier session, genuine conversation was slow to start, with frequent reference to the prompt sheet to keep the session going. Following the experience of the previous year, the prompt related to the internet was included on this sheet, but it was not used by any of the groups participating. One contrast with the session in 2020 was that the stories told were much less related to shared experiences of the students and much more closely related to the texts that had been studied in earlier lectures. This group, which had been sorted into two smaller storytelling circles, generated two thematic clusters, with one group telling what looked very much like ghost stories, on the model of tale 70 (a story about a German knight who encounters a monster in an outdoor privy), while the other group told tales that reflected the themes of sexual infidelity that characterize many of the stories in the Cent Nouvelles nouvelles.27 This may reflect the fact that the group, which had not spent a period on an Erasmus exchange, did not have experiences which bonded them except the experience of being in class. In contrast to the group that met online, they did not refer to the environment in which they met to derive new prompts for their stories, nor did they use the prompts that the online group had suggested. However, they did engage more fully with the material that they had studied: including with some of its challenging aspects. Stories told in the session picked up on sexual and even misogynist themes in the Cent Nouvelles nouvelles.

Following the session in each case, students were invited to reflect on the experience. Here again, the students of 2021 showed a greater awareness of the digital environment, while students in 2022 commented more on the structure and content of the stories told. Once again, this suggests that the environment and the context in which the story is told influence the way in which the exercise is perceived and the sorts of stories told.

Context and blame in reader response

Having established that this might be the case following the 2021 session, I decided to use the 2022 group to investigate whether the environment in which the story was told influenced not only the way that participants told stories, but also the way that they understood stories they encountered. I therefore selected a story from the collection that reflected the pandemic circumstances in which the students were studying and set it as a translation exercise for the group. This story then formed the basis of questionnaires, given to different populations, including students in the group, but also to colleagues in online and in-person sessions, as well as to members of the public and other groups. In each instance, the questions were the same, though they were framed in a different way based on the environment in which the audience had encountered the story and the way in which the story had been presented.

Tale 55 of the Cent Nouvelles nouvelles is a story set in 1450, which the narrative tells us was both a jubilee year for the Church and a plague year. The central character is a young woman who, having resisted the sexual advances of admirers, finds herself struck with the plague and facing death without experience of physical love. She reveals her regret at this situation to an older female friend, who suggests that she remedy it before her demise by approaching one of the men who had previously made advances to her and seducing him. The older woman brings the young man to her and she exhausts him sexually before sending him to locate a second man, to serve as his replacement. Shortly after this, the first man becomes sick and dies, while the second partner is exhausted like the first. He in turn is sent to fetch a third man, and shortly afterwards becomes aware of his own impending death. He returns to the woman, warning her and her current sexual partner of the risk, before expiring in the arms of the priest. The third lover obtains proper care for himself and recovers, as does the woman (cured, as is often said to be the case in this collection, by her prolific sexual activity), but not before she has returned to her parents’ house and seduced and fatally infected their neighbours’ son. The woman, it is implied, uses the incident as a springboard for a career as a sex worker.28

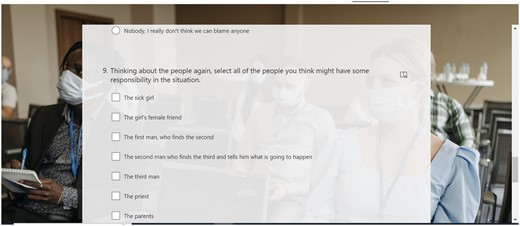

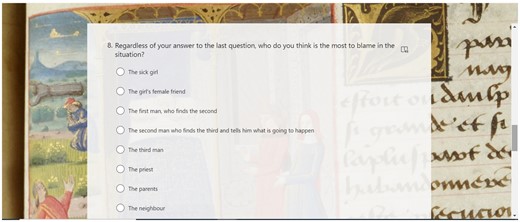

This story, which rehearses fears about unbridled sexuality – and particularly female sexuality in the context of an audience apparently made up only of men – and contagion, gains particular piquancy when told against the background of a pandemic. Students who had translated a section of the story for their coursework were invited to evaluate the extent to which each of the characters in the narrative was to blame for the situation. The same questions were administered to participants in an online seminar, in a seminar in person and to members of the public at a storytelling event. Students were placed in one of two randomized groups and received different questionnaires. One version focused on the usefulness of the translation exercise before moving onto questions inviting participants to attribute blame, whilst the second asked questions about teaching in a pandemic situation, including their preferences for mask wearing, social distancing and other public health measures in the classroom, before they too answered questions as to which, if any, of the characters could be held responsible for the fictional transmission of the disease. Visually, the surveys reinforced the messaging, with the students answering questions about teaching in a pandemic doing so on a form that was superimposed on an image of students in surgical masks in a lecture theatre (see Figure 1.1), while the students in the group answering questions about translation did so on a form illustrated with an image from the manuscript of the Cent Nouvelles nouvelles (see Figure 1.2). In the online seminar, participants were introduced to a number of narratives which repeated the motif of not wanting to die a virgin, drawing attention to the fact that it is a recurrent theme that circulates independently of pandemics or other historical events. The trope is used in the film Airplane II: The Sequel (1982), a clip from which was used to introduce the discussion, and in countless other artistic works.29 The same framing occurred in the in-person seminar, with the addition of students from the class whom I had briefed to recall the pandemic through interventions such as haphazard mask wearing and ostentatious coughing. In the two seminars, the participants were surveyed through direct questions to the audience where they could hear each others’ responses and participate in a dialogue with the arguments made. In the online seminar, this was supplemented by confidential polling, where answers were revealed to the participants only after the polling was over.

Screenshot of online form showing the visual framings of questions relating to students’ reactions to tale 55 of the Cent Nouvelles nouvelles in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic. Form created by Catherine Emerson. Photograph by Pavel Danilyuk, courtesy of Pexels.

Screenshot of online form showing the visual framing of questions relating to students’ reactions to tale 55 of the Cent Nouvelles nouvelles in the historical context of the text studied. Form created by Catherine Emerson. Image courtesy of University of Glasgow Archives & Special Collections: MS Hunter 252.

The results of these different investigations were striking. When questioned directly as to whether you could attribute blame in a pandemic situation, a majority of respondents in all groups said that you could not. This reaction was equally strong regardless of whether or not responses were confidential. When questioned, however, as to who could be blamed in the situation, groups that heard the story in the context of reminders of the pandemic were more inclined to pick one or more characters to blame (the number who blamed a character was more than half in this group and much less than half in the group which had been presented with questions on the text as a literary work). They were both more inclined to attribute blame to one character (typically the woman) and more inclined to ascribe blame to a larger number of characters. In one case, this extended in a confidential anonymous written questionnaire, framed with questions about teaching in a pandemic, to a respondent who argued that the priest was to blame, even though his only involvement in the narrative is to have a plague-stricken character die in his arms, and this was reproduced in a public performance of the story where responses were not confidential. The group answering the confidential survey was also more likely to agree with a statement that the likelihood of infection can be reduced by avoiding risky behaviours than was a group that had not been reminded of the current pandemic context. Participants in online groups confronted with the prevalence of the ‘Must Not Die a Virgin’ trope were particularly resistant to suggestions that blame could be attributed to literary characters, perhaps because of their awareness of the extent to which the story had been shaped by literary conventions. Indeed, this suggestion prompted a near-rebellion in the chat of the online forum where this was attempted, with participants expressing marked reluctance to vote and seeking to persuade others not to do so. By contrast, participants who viewed a very similar live presentation in a room with visible reminders of pandemic infection were much more enthusiastic about condemning the young woman and her plague-vector lovers. The more isolated respondents felt from the risk of infection, the less likely they were to attribute blame to the fictional characters.

Conclusion

In summary, then, the experience of teaching and reading the Cent Nouvelles nouvelles in challenging circumstances demonstrates that the circumstances in which a reader encounters a text affects how the text is understood, just as the circumstances in which a student encounters an exercise affects how they participate in that exercise. In consequence, Flux pedagogy, such as that advocated in pandemic teaching, does become more attractive because engagement with the text is greater and more deeply informed by praxis. Such practical engagement is itself challenging in that it unsettles participants by requiring them to engage with the text – and the process of learning – in new ways. At the same time, the experiment challenges our assumptions about how such texts might originally have been told, and how they might have been understood, by demonstrating how external circumstances can alter the way that narrators relate to each other and the way that readers relate to the text. Rather than settling debates about how the text might have been produced or consumed, this experience further unsettles our appreciation of the Cent nouvelles nouvelles by showing that narration – like comprehension – is shaped by external forces.

Footnotes

See for example Reader-Response Criticism: From Formalism to Post-Structuralism, ed. by Jane P. Tompkins (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980).

Pavan Holur and others, ‘Modelling Social Readers: Novel Tools for Addressing Reception from Online Book Reviews’, Royal Society Open Science, 8.12 (2021), 1–27.

Sharon M. Ravitch, ‘Flux Pedagogy: Transforming Teaching and Leading during Coronavirus’, Perspectives on Urban Education, 17.4 (2020) <https://urbanedjournal.gse.upenn.edu/volume-17-spring-2020/flux-pedagogy-transforming-teaching-and-leading-during-coronavirus> [accessed 8 May 2023]. See also a summary at Sharon M. Ravitch, ‘FLUX Pedagogy: Transforming Teaching & Learning during Coronavirus’, Methodspace, <https://www.methodspace.com/blog/flux-pedagogy-transforming-teaching-learning-during-coronavirus> [accessed 8 May 2023].

Brian Arao and Kristi Clemens, ‘From Safe Spaces to Brave Spaces: A New Way to Frame Dialogue Around Diversity and Social Justice’, in The Art of Effective Facilitation: Reflections from Social Justice Educators, ed. by Lisa M. Landreman (Sterling, VA: Stylus, 2013), pp. 135–50.

Although the French title is deceptively simple, it has given rise to a variety of English translations because of the status of nouvelles in French as both adjective and noun, each with a number of meanings that have changed somewhat over time. Titles used range from that of Robert B. Douglas’s 1899 translation One Hundred Merrie and Delightsome Stories, through Russell Hope Robbins’s The Hundred Tales, published in 1960, to Judith Bruskin Diner’s 1990 The One Hundred New Tales and Wikipedia’s current preferred translation One Hundred New Novellas.

For instance, Edgar de Blieck, in ‘The Cent nouvelles nouvelles, Text, and Context: Literature and history at the court of Burgundy in the fifteenth century’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Glasgow, 2004), introduces the collection by imagining the reaction of a reading public to a scenario in which a sitting prime minister asking his cabinet to provide a collection of racy short stories (p. 1).

For the sources of the tales, see The Early French Novella. An Anthology of Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Tales, ed. and trans. by Patricia Francis Cholakian and Rouben Charles Cholakian (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1972), pp. 17–73; and Raphael Zehnder, Les Modèles latins des ‘Cent nouvelles nouvelles’: Des textes de Poggio Bracciolini, Nicolas de Clamanges, Albrecht von Eyb et Francesco Petrarca et leur adaptation en langue vernaculaire française (Bern: Peter Lang, 2004).

Nicolas Balchov, ‘Du fabliau à la nouvelle’, Cahiers d’études médiévales, 2–3 (1984), 29–37; Nelly Labère, ‘Regarder par le trou de la lorgnette. “L’assez apparante vérité” des Cent Nouvelles nouvelles’, Le Moyen Français, 57–58 (2006), 203–26.

Mathijs Duyck, ‘The Short Story Cycle in Western Literature. Modernity, Continuity and Generic Implications’, Infterérences littéraires/Literaire interferenties, 12 (2014), 75–86.

Bonnie D. Irwin, ‘What’s in a Frame? The Medieval Textualization of Traditional Storytelling’, Oral Tradition, 10.1 (1995), 27–53.

Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron, trans. by Wayne A. Rebhorn (New York: Norton, 2013).

The Cent Nouvelles nouvelles (Burgundy-Luxembourg-France, 1458-c. 1550): Text and Paratext, Codex and Context, ed. by Graeme Small (Turnhout: Brepols, 2023).

Cent Nouvelles nouvelles, ed. by Franklin P. Sweetser, 3rd edn (Geneva: Droz, 1996), p. 22. Subsequent references are to this edition unless otherwise specified, incorporated into the main text as ‘Nouvelles’. English translation from The One Hundred New Tales (Les Cent nouvelles nouvelles), trans. by Judith Bruskin Diner (New York: Garland, 1990), p. 15. Subsequent translations are from this edition, incorporated into the main text as ‘Tales’.

The Cent Nouvelles nouvelles (Burgundy-Luxembourg-France, 1458-c. 1550), ed. by Small. Contrast this approach with that of Roger Dubuis in his introduction to his edition, Les Cent Nouvelles nouvelles, ed. by Roger Dubuis (Paris: Champion, 2005)

Catherine Emerson, ‘Strangers in the Frame: Inside and Outside the Cent Nouvelles nouvelles’, French Studies, 72.3 (2018), 337–49.

An example of this is tale 5 (Nouvelles, pp. 54–59). Set during the Hundred Years’ War, the tale describes the settling of a controversial question as to what can be considered armour. The details of the clothing described – and indeed the practice of wearing armour at all – is so remote from the modern reader as to have very little meaning.

Les Cent Nouvelles nouvelles, ed. by Sweetser, pp. 412–13.

Kieran M. Kennedy and Stacey Scriver, ‘Recommendations for Teaching upon Sensitive Topics in Forensic and Legal Medicine in the Context of Medical Education Pedagogy’, Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 44 (2016), 192–95.

Student participation in these surveys, which were administered as paper surveys in 2018 and 2019 and online in 2020 and 2021, was over 50% of the registered cohort in every case and distinguished students who had participated in the storytelling session from those who had not by means of a specific question on that topic.

Ravitch, ‘FLUX Pedagogy’.

The vocabulary is borrowed from Dennis Dressel, ‘Turn-taking in Collaborative Storytelling. Et puis après (“and then after that”) as a Resource for Resuming Tellings-in-Progress and Negotiating Tellership between Story Episodes’, Linguistik online, 112.7 (2021), 7–25.

Mary B. Nicolini, ‘Is there a FOAF in your Future? Urban Folk Legends in Room 112’, The English Journal, 78.8 (1989), 81–84.

See College of the Holy Cross, Facebook, 13 September 2019, <https://www.facebook.com/collegeoftheholycross/posts/college-campuses-are-ideal-breeding-grounds-for-superstitions-and-urban-legends-/10151308751179963/> [accessed 9 May 2023]; and Anthony J. Kuzniewski, Thy Honoured Name: A History of the College of the Holy Cross, 1843–1994 (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1999), p. 334. For the version of the tale set in Australia, see [Anon.], ‘Cows Can’t Walk Down Stairs’, Public School Stories, 2019, <https://publicschoolstories.tumblr.com/post/176174905917/cows-cant-walk-down-stairs> [accessed 9 May 2023].

Kate Lohnes, ‘Are Cows Really Unable to Walk Down Stairs?’, Encyclopedia Britannica <https://www.britannica.com/story/are-cows-really-unable-to-walk-down-stairs> [accessed 9 May 2023]; Danny Ward, Can Cows Walk Downstairs?, online video recording, YouTube, 18 July 2019, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oA7467hxuU8> [accessed 9 May 2023].

See Ravitch, ‘FLUX Pedagogy’, and idem., ‘Flux Pedagogy’. Key principles of Flux pedagogy include: ‘Don’t try to do the same thing online. Some assignments are no longer possible. Some expectations are no longer reasonable. Some objectives are no longer valuable’: Ravitch, ‘Flux Pedagogy’ (bolding in original).

See Sanctuaire Notre-Dame de Lourdes, Rosary from Lourdes 19/02/2020, online video recording, YouTube, 19 February 2020, <https://youtu.be/iuU_PVAhQGc> [accessed 9 May 2023].

Barry Beardsmore, ‘A Study of Two Middle French Horror Stories’, Nottingham Medieval Studies, 46 (2002), 84–101.

Les Cent Nouvelles nouvelles, ed. by Sweetser, pp. 346–51.

A non-exhaustive list can be found at tvtropes.org. See ‘Must Not Die a Virgin’, TV Tropes, <https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/MustNotDieAVirgin> [accessed 9 May 2023].