-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Seng Fah Tong, Wah Yun Low, Shaiful Bahari Ismail, Lyndal Trevena, Simon Willcock, Physician’s intention to initiate health check-up discussions with men: a qualitative study, Family Practice, Volume 28, Issue 3, June 2011, Pages 307–316, https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmq101

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Background. Although prevalent in primary care settings, men’s health issues are rarely discussed. Yet, primary care doctors (PCDs) are well positioned to offer health check-ups during consultations.

Objectives. This study aims to develop a substantive theory to explain the process of decision making by which PCDs engage men in discussing health check-ups.

Methods. Grounded theory method was adopted. Data source was from 14 in-depth interviews and 8 focus group discussions conducted with a semi-structured guide. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis. Initial open coding captured the concepts of processes from the data, followed by selective and theoretical coding to saturate the core category. Constant comparative method was used throughout the process to allow emergence of the theory.

Results. Fifty-two PCDs from private and public settings were interviewed. PCDs engaged male patients in health check-ups when they associated high medical importance with the relevant issues. The decision to engage men also depended on perceived chances of success in negotiations about health check-ups. A high chance of success, associated with minimal negotiation effort, is associated with men being most receptive to health check-ups. When doctors feel the importance of a particular health issue, they place less emphasis on their perceived men’s receptivity to discuss that health issue in their intention to engage them in discussing it.

Conclusions. Engaging male patients in appropriate health check-up activities requires a series of actions and decisions by the PCDs. The decision to engage the patient depends on the perceived balance between the receptivity of male patients and the medical importance of the issues in mind.

Introduction

In primary care settings, engaging men in health check-ups present many challenges. Men have been noted to be reluctant to seek health check-ups for themselves.1–5 Many factors have been postulated to account for this phenomenon. In the West, their reluctance has been attributed to an attitude that not seeking health care reflects masculinity.6–9 This masculine image is argued to be partly prescribed to men by their society.10 Additionally, many social factors such as poverty and low social class affect their health-seeking behaviour and health.11 In Malaysia, similar poor health-seeking behaviour was noted in a qualitative study among men in an urban setting.12 More recent evidence suggests that men do care about their health and believe in the benefit of health check-ups2 but they often have difficulty in finding good reasons and appropriate contexts to access health care services.13,14 The underutilization of preventive health services has also been attributed to a health system, which is not ‘friendly’ towards male patients.15–17 Therefore, their negative health-seeking behaviour is not just ‘men behaving badly’ but a complex interplay between them, the health care system and society as a whole.17 The health-seeking behaviour of men during their visits to doctors is a dynamic process, which varies depending on the health care providers, the context and the content of encounters.18

Hence, there is a need to consider ways to address men’s health needs,16,19,20 including health check-ups at primary care level.21 Since health check-ups and health screening activities receive little attention from men, doctors at the primary care level need to be encouraged to be proactive in bringing up the issue for discussion during clinic encounters with them.21,22 However, such issues are rarely brought up during consultation. Among the barriers identified in the literature are a negative perception of men’s health-seeking behaviour,4,5 inadequate services addressing specific needs for men21,23 and a low level of awareness in the community; hence, poor demand for men’s health services.24

An effective strategy is clearly needed to help primary care doctors (PCDs) successfully engage men in preventive health care. However, the available evidence only focuses on possible barriers to men receiving preventive health care and does not address the specific barriers to initiating the discussion on health check-ups within the consultation. Understanding this process and its underlying theory is important because it may help in designing a strategy to improve the uptake of men’s health check-ups in Malaysian primary care.25 This study aims to develop a model from empirical data that explains the decision-making process by PCDs in engaging men in health check-ups.

Methodology

Grounded theory was adopted in line with the stated aim of this study to understand the process and action involved in doctors’ decision making on health check-ups for men.26

Study setting and recruitment of participants

Primary care outpatient services in Malaysia are delivered through government-funded public clinics and private self-funded clinics.27 These two sectors vary in their workload, administrative system, patient profile, manpower and resources, which potentially affect their practice behaviour. Therefore, in our sampling matrix, we included a range of PCDs in Malaysia from both genders, various age groups, places of practice, nature of practice (either private or public) and qualifications. Two regions were selected (Klang Valley and Kelantan) because of their different cultural and socio-economic profiles. Klang Valley, encompassing Kuala Lumpur and Petaling Jaya, is an urban metropolitan area, which is more advanced in economic development compared to the state of Kelantan. Participants were invited through several channels. Invitation letters were sent to 200 private PCDs, who were members of the Academy of Family Physicians of Malaysia (AFPM). These 200 PCDs were short listed from the list of AFPM members practising in Kuala Lumpur and Petaling Jaya. For public clinics, contacts were sought through the Chair of the Selangor, Division of Family Medicine Specialists Association (FMSA). All 25 members of FMSA in the Selangor division were invited. Furthermote, the heads of two primary care centres (one public health clinic in Petaling Jaya and one academic primary care centre in Kelantan) were also contacted to help recruit doctors from their respective areas. Finally, three personal invitations were given to key opinion leaders in primary care organizations. From all the recruiting strategies above, 20 PCDs from AFPM, 10 FMSA members, 19 PCDs from contacts via heads of clinics and all three key opinion leaders accepted the invitation to participate. The venues for interviews and focus groups were arranged to suit participants’ preferences. A total of 14 in-depth interviews (IDIs) and 8 focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted. The number of doctors in each group ranged from 3 to 10 with a median of 4. None of the doctors involved had any formal training in andrology or men’s health.

Data collection

FGDs and IDIs were chosen as the data collection methods. FGD provides an opportunity for doctors to exchange ideas and stimulate further thoughts beyond their own original ideas. IDI allows the expression of views that the participant may not want to reveal in the presence of their peers.28 All FGDs and IDIs were moderated and conducted by SFT in English because English is the commonly used language among the medical fraternity in Malaysia. Both FGDs and IDIs were guided by the same semi-structured questionnaire to stimulate discussions on participants’ understanding of men’s health, their decisions and practices related to men’s health check-ups or screening and barriers and motivators to initiating men’s health check-ups and screening. A free-flowing discussion was encouraged to gain unrestricted opinions on each topic. It was emphasized that the discussion was not meant for assessment. The participants in the FGDs were confined to similar training backgrounds to avoid intimidating situations between PCDs with postgraduate training and junior PCDs. Participants were briefed on the study objectives and ground rules to ensure confidentiality. Permission was sought to audiotape the session and written informed consent was obtained after the briefing. A note taker assisted all FGDs to help with audiotaping and recording who were conversing. All sessions were audio taped with permission and transcribed verbatim for analysis. All transcripts were checked for correctness of transcription before analysis.

A total of 52 PCDs from various backgrounds and experiences participated. There was wide diversity in the age, degree of training and experience and good representation from both male and female doctors (Table 1). More private doctors were involved in IDIs because they were not able to accommodate their time for FGDs. Three key opinion leaders, who hold important positions in the various professional bodies related to primary care in Malaysia, were interviewed individually in case they exert a significant influence on the group dynamics in FGDs. The average length of time for the FGD was 62 minutes, ranging from 46 to 77 minutes. IDIs averaged 49 minutes, ranging from 31 to 74 minutes.

| Characteristics | Number of participants (n = 52) |

| Age range (years) | 30–69 |

| Male to female ratio | 19:33 |

| Postgraduate to basic degree ratio | 26:49 |

| Urban to rural practice ratio | 41:11 |

| Characteristics | Number of participants (n = 52) |

| Age range (years) | 30–69 |

| Male to female ratio | 19:33 |

| Postgraduate to basic degree ratio | 26:49 |

| Urban to rural practice ratio | 41:11 |

| Characteristics | Number of participants (n = 52) |

| Age range (years) | 30–69 |

| Male to female ratio | 19:33 |

| Postgraduate to basic degree ratio | 26:49 |

| Urban to rural practice ratio | 41:11 |

| Characteristics | Number of participants (n = 52) |

| Age range (years) | 30–69 |

| Male to female ratio | 19:33 |

| Postgraduate to basic degree ratio | 26:49 |

| Urban to rural practice ratio | 41:11 |

Data analysis

Each FGD was analysed as one unit of analysis. The first three transcripts (two IDIs and one FGD) were read repeatedly by SFT to gain an overall understanding of the interviews. This was followed by ‘line-by-line’ coding of the first three transcripts to identify in detail the concepts expressed by the participants. The initial analysis generated 356 concepts, which were consolidated into categories, subcategories and their properties by constant comparison. The transcripts and the summary of the concepts were read by WYL and SW to ensure validity of coding. A tentative conceptual framework emerged through these procedures. This framework was refined and adjusted following the analysis of the remaining transcripts in an iterative process as described in grounded theory.26 An emerging core category was selected, followed by selective coding and, finally, theoretical coding of causal–effect relationship was applied as it fitted the data.29 Throughout the process of constant comparison and coding, memos were written to capture the ideas and thoughts to allow the emergence of theory. A memo was written at the end of coding for each transcript to capture an overall impression of each interview in order to provide a distant view of what the participant’s opinions are, as opposed to the detailed analysis of line-by-line coding. Memos also acted as reflexive notes for the researcher’s thoughts to minimize potential bias when analysing the transcripts.30 Theoretical saturation was achieved in the analysis of the 11th transcript (eight IDIs and three FGDs) when no new subcategories or properties for the core category emerged from the following seven transcripts. After the initial analysis of 18 transcripts, four more IDIs were conducted to validate the theory, and we were satisfied that the theory fitted the decision-making process. To improve the rigour of data analysis, all participants were invited to group feedback sessions where the main findings and tentative theoretical framework were presented. The participants were encouraged to provide feedback on whether the findings match the line of decision-making process. A total of seven participants provided feedback; five attended a group feedback session and two via individual session. The analysis was aided by the qualitative data management software, QSR Nvivo 8. The study was approved by the Ethics Committees from the University of Malaya, the Ministry of Health Malaysia and the University of Sydney.

Results

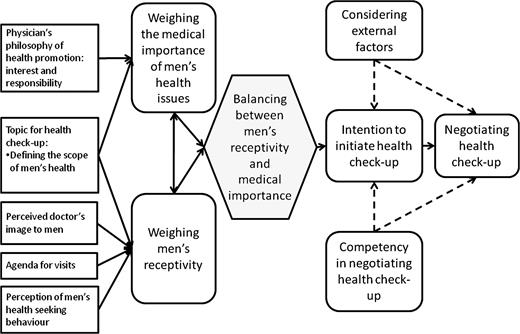

The findings showed that PCDs in Malaysia have difficulty initiating health check-ups with men in primary care settings especially in areas perceived to be sensitive, such as, sexual reproductive and psychosocial health. The doctors’ intention to initiate health check-ups started with the balance between how receptive men were and how important the medical issues to men as perceived by PCDs (Fig. 1). However, even with strong intention to initiate health check-ups, the intention could be modified and the actualization of health check-ups was influenced by external factors and their competency in approaching men in health check-ups. This paper will focus on the balance between perceived receptivity of men and perceived medical importance in men’s health issues.

Process of the doctor's decision making to engage men in health check-up

Weighing the medical importance of men’s health issues

The process of weighing medical importance was, essentially, the degree of emphasis the doctor confers on a particular medical condition during an encounter with his/her patient. The doctors weighed the medical importance of men’s health check-ups based on their own understanding of the topic and scope of men's health, their own interests and responsibility to health promotion in primary care (Fig. 1). In a FGD, one doctor spoke about her initiative to inquire more into areas that interest her and the opinion was supported by others.

I look at things that sort of … I feel that if the things interest me more, I tend to screen it more often and ask more … such as smoking

—FGD, 39-year-old female public doctor

Again, it comes back to the basic, as really the interest and the man power. So we're looking into a specific men health issue. It is more than what we do in extra [in our routine].

—FGD, 42-year-old female public doctor

In an IDI, a doctor admitted not addressing men's health issues because she is not interested.

Because I'm not really interested on men's health issues, so I just, I mean, delve only on the surface and I don't go into it.

—IDI, 45-year-old female private doctor

FGDs provided an opportunity for the participants to debate on the scope of men's health, which influence their intention of what to screen in health check-ups. Doctors, who took note of cardiovascular disease as a common problem affecting men would emphasize cardiovascular risk assessment (include smoking) as part of health check-ups. This was additional to male-specific disorders, such as sexual reproductive disorders, which have often been advocated as the main issues in men’s health.

I know that people have looked at like sexual problems, like erectile dysfunction … and now andropause … that's another err … the main domain of men's health, but the other domain, I think cardiovascular screening and the cancer screening also … that is what we usually do

—FGD, 38-year-old female public doctor

On the other hand, in the same FGD, some doctors who emphasize male-specific disorders as the main concern for men’s health would make sexual health as the main agenda in men’s health check. They would also enquire about cardiovascular risk factors and family relationships but saw these issues as ‘underlying diseases’ to sexual health.

I think, for us as a GP, our role is to screen ED to detect a ‘bigger’ underlying disease, so our job is to screen for ED get down to the underlying disease

—FGD, 47-year-old male private doctor

Others also took on a biopsychosocial approach to health.

I will provide screening for their general well being, of course lipid profile, then, keep up to date their social problems. I screen all areas

—FGD, 29-year-old female public doctor

In an interview with one of the key opinion leaders, the doctors who saw health promotion as the responsibility of primary care would proactively provide health check-ups.

We will start screening them for various risk factors to attenuate the cause of a disease. Delay the onset of the complication as well

—IDI, 69-year-old male private doctor

However, if the doctors had a negative perception of men’s health check-ups, they would not put any effort to initiating it.

I, I think, there is no big deal about men's health. As I said, I don't think you should go and waste so much of your time. The most important thing is practicality. For a doctor … the most important is actually must be practical. If it's not practical, you can forget it

—IDI, 68-year-old male private doctor

In short, their perception of responsibility and the importance of the men’s health check-ups would determine the priority and degree of emphasis during encounters with male patients. The responsibility of health screening was the doctors’ philosophical stance on health screening.31 Hence, the weight the doctors gave to a particular men’s health issue did not change with the agenda for visits but the priority to bring up the issue during encounters with men depended on their perception of men’s receptivity to health check-ups (Fig. 1).

Weighing men’s receptivity to health check-ups

The degree of receptivity to health check-ups was perceived to be driven by the willingness of men to discuss health check-ups during consultations. The doctors’ perception of the men’s degree of receptivity influences their intention to raise the discussion on health check-ups. The ultimate degree of receptivity was when the men themselves requested a health check-up or a particular screening test. In so doing, the men openly declared their interest in health check-ups. In these circumstances, doctors would not hesitate to undertake the health check-ups. On the other end, the degree of receptivity was lowest when men refused to discuss health check-ups by articulating their disapproval or conveying uneasiness non-verbally. This is demonstrated in one of the FGDs:

Sometimes we do know the outcome. I suggest to him why not you [the patient] get these done: why not screen for cholesterol, diabetes. Usually I do suggest for such screening but such patients who come for screening are very few. Very few will ask for it.

—FGD, 45-year-old male private doctor

I do get patient like that too, they all want to do blood test, “doctor I want to check my blood”, that's what they said. So I proceed with blood test. But, very seldom I propose to them. Tell you very frankly. Very seldom I offer.

—FGD, 40-year-old male private doctor

This perception of men’s receptivity was shaped by four main factors (Fig. 1): their perception of the health-seeking behaviour of their male patients; their image as health care providers to men; the agenda of the encounters and the topic of men’s health check-ups. Less sensitive health issues, like cardiovascular risk assessment, were perceived as receptive by many male patients whereas sensitive issues, like sexual health, were subjected to heavier influence by the other three factors.

Doctors associated men’s positive attitudes towards health with receptivity to health check-ups. When men were perceived as interested in health information, placed health as a priority and were willing to pay for a health check-up, then, they would probably be interested in a broader discussion about their health. Older men were also perceived to be interested in maintaining health. Both the doctors in FGDs and IDIs revealed similar experience.

Men who are aware of health are quite happy when you give a card, an appointment card. They do come back to you and said ‘I want a health check, can you please check’

—FGD, 45-year-old male private doctor

Men over forty, for example, I think they will, they have already got that idea that they are about to go for health check. And I think, especially the government officers, the government has a compulsory program for health check … they accept [the idea of health check-up]

—IDI, 44-year-old female private doctor

On the other hand, if the doctors had a negative perception about men’s health-seeking behaviour, they would perceive men to be resistant to health check-ups. This substantially reduced their intention to discuss a health check-up with men. Most of the discussion in the FGDs raised this issue among male and female doctors. For example, stereotyping men into the hegemonic image of masculinity contributed to the perception of low receptivity to health check-ups. Men were thought to be in denial of health issues, have no belief in health check-ups, intent on guarding their masculinity image and fearful of long-term treatment. Men were also thought to have low receptivity to health check-ups if doctors believed that a sexual health discussion with men was a taboo subject.

The men seem to think, perhaps health screening is not one of their priorities. The priority is to earn money and be the breadwinner for the family. That's a higher priority for them. They perceive health is not important.

—FGD, 47-year-old female public doctor

In that sense … it is partially a cultural context that guys here don't openly talk about this subject and secondly is the ignorance

—FGD, 51-year-old male private doctor

The assumption of their image as the health care providers to men also affected their perception of men’s receptivity. If there was an established rapport with male patients, the men would be perceived as receptive to the discussion on health check-ups. A rapport often develops over a period of time following repeated encounters with men, such as for the treatment of chronic illnesses or prolonged engagement of the doctors as men’s family doctors.

It depends on the relationship em … you know that patient trusts you and then you can ask, but for initial [encounter] normally we don't ask such questions [about sexual health]

—FGD, 41-year-old female public doctor

Gender issues between male patients and female doctors were often raised as a barrier to discussing men’s health issues by some, but not all, female doctors. Men were perceived as not being comfortable, hence not receptive, to discussing sensitive areas, such as sexual health. While this was true in many situations because of sociocultural influences as discussed in many FGDs, this might not entirely be due to gender since some female doctors were confident in dealing with sexual health matters with their male patients. In one female doctor’s experience, many of her male patients have been receptive to discussing sexual health matters. Therefore, it was more an issue of how she perceived her professional relationship to male patients. The assumption of her confident image to her male patients influenced her perception of the men’s receptivity.

If you open up and you show that, you will and willing to tackle whatever problem they have, I think they will open to you. So far I don't have problem. Normally they … they will open up. I think even to talk about sex, about whatever, I think I don't have problems. I have gay patients, the transsexual, normally they open up to me. I, I don't have a problem.

—IDI, 46-year-old female public doctor

A positive image of competency also supports the doctors’ perception that men would be receptive to discussing men’s health issues. In the following example, gender was, again, not an issue. Many members agreed with her in the FGD.

I think the patients screen us first, patients screen us first … for example if they know you and they are comfortable with you. Then we offer [health check]. The discussion then is very easy.

—FGDs, 42-year-old female public doctor

The other factor that affected the degree of men’s receptivity was the agenda for the encounters. If the agenda for the encounter was to have a health check-up, there would be total receptivity. However, varying degrees of receptivity were seen with acute and follow-up consultations. In an acute consultation for minor ailments, the receptivity was high if the doctors managed to seize the opportunity to talk about health issues relevant to their acute complaints. Many examples in the FGDs and IDIs support such claim.

… the question of … which, which subject to introduce depends on your complaint. Okay … is just like you take an URTI case [for example], then you can go into [the topic of] smoking. You can just check the weight and height, and if it goes beyond [the normal level] and you said ‘you are, you know, you are above [recommended] weight level. I think you have to look at lipid profile and, because you are going along like that, they can understand all these

—IDI, 62-year-old male private doctor

The degree of receptivity was also high if, during a consultation, the doctors were able to recognize non-verbal cues from men that they wished for further discussion on health check-ups. This often happened with sexual health. The hidden agenda signified a higher degree of receptivity to discussions on the issue.

If the patient frequently comes to us with er …unresolved problem, maybe they have something that they want to tell us about [but] they didn't tell us. So, in that case, we maybe … will ask about that. Otherwise, you don't do the ‘proactive screening’ for the healthy patients.

—FGD, 30-year-old female public doctor

Male patients who came for follow-up on chronic illnesses present different levels of receptivity because a rapport might have developed and a trusting relationship established. They were more receptive to discussing health matters because of their pre-existing illness. For example, men were perceived to be more amenable to talking about sexual health matters during chronic disease consultations.

They [male patients], they do talk, particularly when these people have a disease like hypertension, they are on medications like anti-diabetic or anti-hypertensive

—FGD, 40-year-old male private doctor

Balancing men’s receptivity and medical importance

In this regard, when doctors feel the importance of a particular health issue (hence putting more weight to it), they place less emphasis (hence less weight) on their perceived men’s receptivity to discuss that health issue in their intention to engage them in discussing it (Fig. 1). For example, asking about sexual problems, which was perceived as not easily acceptable by many patients, was mainly initiated when it seemed to warrant such assessment because the patient was at risk, as illustrated below in one of the FGDs:

if you know that diabetes is one of the reasons for patient's sexual dysfunction, yes. You will trigger the question and ask the patient in more detail

—FGD, 39-year-old female public doctor

(nodding) Diabetes, hypertension which are high risk [conditions for sexual dysfunction]. No risk [of sexual dysfunction] is really … [giggling] difficult. The example is patient with URTI … (laughing), I won't ask about sexual dysfunction

—FGD, 41-year-old female public doctor

Similarly, men’s receptivity played a smaller role to doctors who perceived cardiovascular risk assessment as an important issue. Hence, cardiovascular risk assessment was often offered during encounters that were unrelated to heart disease. Other issues that were perceived as important were routine blood pressure measurement, psychosocial health when men presented with repeated minor complaints, sexual health when men were at risk of complications from medication and cancer screening among men with a positive family history.

In fact, one example is about, just two weeks ago, a patient came in, a forty plus year-old Indian man, came in for just a normal cough and cold and so on. And then, I asked him, “Have you ever tested your blood?” He said he has not tested his blood for long time. The last test he did was eight or ten years ago. So I said, “Since you know you are forty something, so why don't you just do a sugar and cholesterol test.”

—IDI, 45-year-old male private doctor

On the other hand, if a particular component of the health check-ups was perceived as less important to male patients, such as when a doctor saw it as a waste of money, the male patients must then demonstrate a high degree of receptivity before doctors would initiate a discussion on it. For example, the degree of receptivity to laboratory assessment of serum tumour markers needed to be very high to counter the low medical importance of such a screening test before the test was offered.

I don't do it [tumour marker testing]. I think it's just a waste of patient's money. I don't believe it. Any patient who asks me [for that] also I will not going to do. My standard is that, I don't do tumour markers testing. I'll tell off the patients. Unless they insist they want the tumour markers

—IDI, 44-year-old male private doctor

Therefore, the doctors would often propose a health check-up when there is at least some degree of men’s receptivity to it. Rarely, more elaborate health check-ups, such as screening, would be offered proactively when the male patients were less receptive. In an IDI, a doctor expressed his experience in offering blood tests to his male patients:

Usually, if they are interested in their health, only then I will give them the possibility of a screening test, rather than pushing it onto their face

—IDI, 38-year-old male private doctor

Validation of core category

The concept of balancing the medical importance of men’s health issues and perception of receptivity of men to health check-ups was presented at the feedback sessions. The model was well accepted by all doctors in the feedback sessions.

I think the diagram reflects the whole idea of how the doctor is thinking, as discussed before, probably some other elements affect the perception, for example gender, as we talk about sexual issues to male patient.

—Group feedback, 42-year-old male private doctor

Yes, it is very true about the balance of receptivity and medical importance

—Group feedback, 38 year-old female public doctor

The concepts of medical importance and the perception of men’s receptivity were re-emphasized. One of the respondents has equated the concept to asking men about smoking cessation to sexual health screening. Some men became defensive and deter the doctor from asking about smoking.

Actually, I think it [receptivity to discussion on ED] is like smoking also. If you feel like, you want to advice the patient to quit and the patient is not ready, they do get defensive

—Individual feedback, 38-year-old female public doctor

Discussion

This study elaborates the process of balancing ‘medical importance’ and ‘men’s receptivity’ when doctors initiate a discussion about preventive men’s health check-ups. As the final decision to engage in having a health check-up requires mutual agreement between patients and health care providers (PCDs in this case), the receptivity of men to health check-ups is pertinent. The effective engagement of men in this issue requires an assessment of men’s receptivity and a correct emphasis on the medical importance of men’s health issues for that patient.

This study also demonstrates that the assessment of men’s receptivity to health interventions reflects the experience and attitudes of the treating doctor. Most doctors perceived that men have negative health-seeking behaviour. This finding is in keeping with the results of two other studies on doctors’ opinions about men’s health-seeking behaviour.4,5 However, these findings contrasted with more recent literature involving interviews with men in the community. In the UK, men were noted to be actually interested in health check-ups.2,32,33 A study in Australia interviewing men about what men valued during medical consultations noted that men have specific needs when communicating with doctors. They preferred doctors to be frank and competent, demonstrate empathy and prompt in problem solving.34 Men in an urban setting in Malaysia valued the importance of a health check-ups but the effort to come forward proved to be an obstacle and was worsened by the perception that doctors were disinterested.12 The contrasting opinions between treating doctors and male patients posed a significant area of risk in efforts to engage men in health check-ups. Therefore, there is a need to improve this miscommunication between doctors and male patients so that assessment of the men’s receptivity is not based on perception but instead on objective criteria.

We also noted that doctors varied their consideration of the importance of men’s health issues in each encounter with male patients. How much emphasis the doctors placed on the men’s health issues depended on their exposure to and understanding of those issues. Some doctors who saw a link between erectile dysfunction (ED) and complications of cardiovascular disease would want to screen for ED. Those doctors who emphasized holistic care of men (a biopsychosocial model of care) would want to enquire about general well-being. It implies that the doctors need to be well-informed on what constitutes and is relevant to men’s health issues before optimal offering of health check-ups. Creating this awareness and knowledge could be and has been an area targeted by many continuous medical education programmes, such as seminars, conferences and practice guidelines.35,36

The theory of reasoned action approach provided valuable concepts and rendered the researchers sensitive to the core categories during the final stage of theoretical coding. This process of coding is in keeping with the recommendation that the use of existing theory has to earn its way into the analysis.29 The model of reasoned action approach describes three variables that influence the intention, which is believed to immediately precede the intended behaviour. The three variables are the attitudes which are affected by the behavioural beliefs and outcome evaluations of the intended behaviour; the norms which are affected by the beliefs and motivation to comply with the intended behaviour; self-efficacy which is affected by the belief in ability to control the intended behaviour and finally, actualization of the behaviour which is also affected by skills and environmental factors.37 While the theory of reason action provides a comprehensive framework explaining human behaviours, it does not provide sufficient details of what is emphasized in the decision making by the doctors in considering men’s health check-ups during primary care consultations. In the context of decision-making processes in men’s health check-ups, the concepts of attitudes, external factors and competency in negotiating this are emphasized. The concept of weighing men’s receptivity illustrates the outcome evaluation of success in engaging men in health check-ups. A high degree of receptivity would result in a more positive outcome. As noted in the empirical data, perceived high degree of receptivity motivated the doctors to discuss men's general health check-ups, whereas the concept of weighing medical importance is influenced by the doctors’ belief in the benefit of performing the health check-ups.

The concept of ‘weighing’ also illustrates that every man is assigned with different degree of receptivity and medical importance based on the doctors’ assessment. This process of ‘mental weighing’ was first introduced in 199938 when Mullaney described how an identity is assigned to an individual. Different acts performed by an individual are weighed differently by the observer in the process of assigning the individual’s identity. The same concept is also used to illustrate how people weigh the cues and indicators before they decide to switch roles in their day-to-day activities.39 While the concept of weighing is long established, we need to know what is weighed in different context. Here, in the context of deciding whether to engage men in health check-ups, the concept of weighing can be extended to weighing perceived men’s receptivity and medical importance.

The strength of this study is that the model was developed through empirical evidence by IDI and FGD. The steps recommended by the methodology of grounded theory were applied as much as possible to ensure the maximum fit of the emerging model.26,29 Theoretical sensitivity of the principal researcher was developed by active participation in men’s health projects in Malaysia12 and practising as a PCD in the local context. Participant validation and further IDIs, which confirm the emerging fit of the model provided evidence of rigour in the analysis. The rigour of the findings could have been strengthened by direct observation of the participating doctors’ behaviours during clinic encounters. However, this would compromise the confidentiality of the encounters and possibly influence doctor–patient interactions. The openness of the information provided by the participants was optimized by establishing rapport with them. Hence, we believed that further observation would not have yielded any significant advantage.

Conclusions and its implication

The intention to engage men in preventive health check-ups depends on the crucial balance between the receptivity of male patients and the medical importance of the issues in mind. Further actualization of the intended behaviour (negotiating a health check-up) is only possible after this intention is established. The findings also imply that error in any of the two factors would compromise the decision in initiating a health check-up with men. The concept of balancing men’s receptivity and medical importance have the potential to inform better intervention strategies. The doctors need to be aware of their assumptions and the validity of cues they might be using in assessing men’s receptivity of having health check-ups. Addressing the competency of the doctors in performing health check-ups and external factors alone are insufficient in bringing about optimal practice of health check-ups for men.

Declaration

Funding: Short-Term-Research-Grant from the University of Malaya (FS241/2008C). The funding institution has no role at all in the design, conduct and analysis of the study and the writing and submission of this manuscript.

Ethical approval: Ethics and Medical Research Committee, Ministry of Health Malaysia (NMRR-08-1516-3079); Medical Ethics Committee, University Malaya Medical Centre (679.28); Human Research Ethics Committee, The University of Sydney (03-2009/11490).

Conflict of interest: All authors declare that (i) no author has support from any company for the submitted work; (ii) no author has relationships with any that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; (iii) their spouses, partners, or children have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work and (iv) no authors has non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

We would like to thank University of Malaya for the ethics approval and funding the study. We also wish to thank the Human Research Ethics Committee for approving the study. We greatly appreciate the contribution of all participating PCDs in providing valuable data to the study.