-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Luigi Di Biase, Jacopo Marazzato, Hybrid ablation for persistent and long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation: is the grass really greener on the other side?, EP Europace, Volume 25, Issue 5, May 2023, euad136, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euad136

Close - Share Icon Share

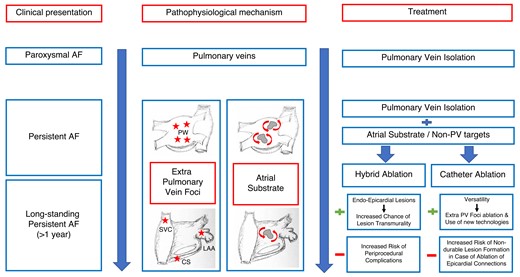

CS, coronary sinus; LAA, left atrial appendage; PW, posterior wall; SVC, superior vena cava.

This editorial refers to ‘Hybrid atrial fibrillation ablation: long-term outcomes from a single-center 10-year experience’ by L. Pannone et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/euad136.

Early rhythm control therapy has emerged as the winning strategy to reduce the risk of major cardiovascular outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).1 In this setting, catheter ablation (CA) proved superior to antiarrhythmic medications2 especially when pulmonary veins (PV) are targeted in patients with new-onset arrhythmia and paroxysmal presentation.3 However, PV isolation (PVI) is associated with a 5-year freedom from atrial arrhythmia as low as 20% in patients undergoing CA for persistent (PeAF) or long-standing persistent (>1 year) AF (LSPeAF).4 The reason should be sought in the role of non-PV foci and atrial substrate remodeling in this population.

Nevertheless, the best ablation strategy to treat safely and effectively patients with PeAF and LSPeAF is still unclear. In the STAR-AF II trial, Verma et al. found no benefit in linear ablation or ablation of complex fractionated electrograms (CFAEs) when added to PVI in PeAF patients. In fact, the completion of atrial lines and their electrophysiological assessment can be greatly difficult to achieve.5 Furthermore, the feasibility of CFAE ablation is controversial due to the currently limited understanding in their pathophysiology.

Of note, other non-PV foci—not tested in the STAR-AF II trial—have recently emerged as promising ablation targets in addition to PVI to improve CA outcome. Not only did the left atrial (LA) posterior wall prove to harbor non-PV triggers but also to play a paramount role in the atrial remodeling process in non-paroxysmal AF.6 However, in this setting, the absence of a standardized CA approach has led to conflicting evidence in different experiences.6 In addition, thick epicardial connections crossing this anatomical structure have been described and may represent a hindrance to achieve complete lesion transmurality when ablated with an endocardial approach alone.6 This is even more important when substrate ablation represents the only way proven in non-paroxysmal AF patients with recurrent arrhythmia and proof of PVI on repeat CA procedure. The best ablation strategy is even less clear in this scenario.

For this purpose, hybrid ablation strategies combining surgical thoracoscopic and endocardial LA ablation have been developed to achieve better lesion formation in non-paroxysmal AF patients requiring substrate ablation in addition to PVI. However, the current guidelines limit standalone hybrid ablation as first-line strategy due to concerns on procedural safety and efficacy.7,8 Furthermore, despite the encouraging results of the recent CONVERGE trial9 showing an improved 1-year outcome of a combined endo-epicardial PVI and posterior wall ablation (Hybrid Convergent group) compared with the standard-of-care (endocardial CA) in patients with PeAF and LSPeAF, data on long-term outcome have not been hitherto investigated.

In this issue of the journal, in a large retrospective cohort of patients, Pannone et al.10 describe the long-term outcome of hybrid ablation for PeAF and LSPeAF in a high-volume European center. In most cases (71%), the procedure was performed as first-line AF ablation whereas it represented a re-do strategy in less than 30% of patients in whom durable PVI was observed in roughly 83%. Each procedure was carried out under general anesthesia as a one-step approach where thoracoscopic PVI and posterior wall debulking were followed by endocardial touch-up of electrical breakthroughs detected by LA mapping. Of note, further endocardial and epicardial lines were added at the operator’s discretion, including CFAEs (26%). The overall long-term atrial arrhythmia freedom was 47.5% at 5 years, and LA volume and AF recurrence during the blanking period were the only independent predictors of ablation failure. However, hybrid ablation was affected by the significant periprocedural complication rate (12%) and up to 30% of these patients required medical/surgical intervention for LA perforation, pericardial tamponade, and pneumothorax.

The authors should be praised and commended for their effort to evaluate the role of hybrid ablation to treat PeAF and LSPeAF after the completion of the longest follow-up to date in this setting. However, the overall long-term hybrid ablation efficacy is quite disappointing and potentially biased by the adopted study methodology.

First, evaluating a mixed patient population with unclear indications for hybrid AF ablation and the non-homogeneous distribution of the number of patients in the evaluated study groups raise concerns on the actual long-term outcome in the investigated cohort. A further source of bias is represented by the heterogeneous endo-epicardial lesion sets performed on the operator’s discretion, a common issue shared with other studies investigating hybrid ablation.9

Second, assessing more than 5000 patients undergoing 7145 AF ablation procedures over 18 years, Winkle et al. have recently shown an almost equivalent rate of long-term sinus rhythm (SR) maintenance in a non-paroxysmal AF patient cohort undergoing standard CA.3 However, compared with hybrid ablation,10 CA was associated with a significantly lower complication rate (1210 vs. 4.5%3) procedure duration (262 ± 6510 vs. 114 ± 373 min) and fluoroscopy time (23.4 ± 10.110 vs. 13 ± 383 min) especially when contact force sensing catheters and high-power short-duration strategies were implemented in this population.3

Third, hybrid AF ablation generally provides a standardized lesion set in every patient. However, non-PV foci play a key role in non-paroxysmal AF11 and—when targeted for ablation after empirical PVI—they can lead to identical or even better long-term outcomes.12 In this regard, a propensity score matching analysis evaluating left atrial appendage isolation (LAAI) on top of PVI13 showed that the 5-year SR maintenance off-antiarrhythmic drugs in patients who underwent LAAEI were 68.9% vs. 50.2% in standard CA alone (P < 0.001). Similar results are expected when the endocardial debulking of the LA posterior wall is performed empirically after PVI in PeAF patients.14

Therefore, in addition to PVI, endocardial CA of non-PVI targets seems safer than hybrid ablation with comparable—if not better—long-term SR maintenance in a PeAF and LSPeAF population.

Questions is what in whom? In our experience, an ablation strategy based on empirical PVI and LA posterior wall debulking followed by isoproterenol challenge to detect and ablate any right- and left-sided non-PV triggers proved feasible and associated with even better long-term outcomes compared with PVI and posterior wall ablation alone in patients with PeAF and LSPeAF.11,15 In addition, we strongly believe that empirical LAA isolation is paramount in this population especially when PVs test already isolated in re-do procedures.11,13,15

In conclusion, despite being promising, more data are required to provide conclusive recommendations for hybrid ablation, especially as first-line treatment, in patients with drug-refractory PeAF and LSPeAF. Meanwhile, endocardial CA represents a feasible, safe, and effective strategy in this setting.

Despite looking greener, we are not ready for prime-time hybrid ablation.

Funding

None.

References

Author notes

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of Europace or of the European Society of Cardiology.

Conflict of interest: None declared.