-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kevin J Um, William F McIntyre, Jeff S Healey, Pablo A Mendoza, Alex Koziarz, Guy Amit, Victor A Chu, Richard P Whitlock, Emilie P Belley-Côté, Pre- and post-treatment with amiodarone for elective electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis, EP Europace, Volume 21, Issue 6, June 2019, Pages 856–863, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euy310

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Clinicians frequently pre-treat patients with amiodarone to increase the efficacy of electrical cardioversion for atrial fibrillation (AF). Our objective was to determine the precise effects of amiodarone pre- and post-treatment on conversion efficacy and sinus rhythm maintenance.

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of trials comparing pre- and post-treatment for electrical cardioversion with amiodarone vs. no therapy on (i) acute restoration and (ii) maintenance of sinus rhythm after 1 year. We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE from inception to July 2018 for randomized controlled trials. We evaluated the risk of bias for individual studies with the Cochrane tool and overall quality of evidence with the GRADE framework. We identified eight eligible studies (n = 1012). Five studies were deemed to have unclear or high risk of selection bias. We found the evidence to be of high quality based on GRADE. Treatment with amiodarone (200–800 mg daily for 1–6 weeks pre-cardioversion; 0–200 mg daily post-cardioversion) was associated with higher rates of acute restoration [relative risk (RR) 1.22, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07–1.39, P = 0.004, n = 1012, I2 = 65%] and maintenance of sinus rhythm over 13 months (RR 4.39, 95% CI 2.99–6.45, P < 0.001, n = 695, I2 = 0%). The effects of amiodarone for acute restoration were maintained when considering only studies at low risk of bias (RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.10–1.36, P < 0.001, n = 572, I2 = 0%). Adverse effects were typically non-serious, occurring in 3.4% (6/174) of subjects receiving amiodarone.

High-quality evidence demonstrated that treatment with amiodarone improved the restoration and maintenance of sinus rhythm after electrical cardioversion of AF. Short-term amiodarone was well-tolerated.

Introduction

Electrical cardioversion is commonly performed in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).1 Although electrical cardioversion restores sinus rhythm in 75–87% of patients, the rate of recurrence is 57–63% within 4 weeks.2–6

Up to 25% of patients receive a rhythm-controlling agent before electrical cardioversion.4,7,8 Pre-treatment with antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) has been reported to improve the acute restoration and long-term maintenance of sinus rhythm.9,10 Class I and III AADs inhibit fibrillatory circuits by decreasing the conduction velocity of cardiomyocytes and lengthening the effective refractory period, respectively.11 The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) suggests that anti-arrhythmic pre-treatment prior to cardioversion is reasonable, but bases this recommendation on level ‘B’ data [derived from a single randomized controlled trial (RCT) or large non-randomized studies].12

Amiodarone is a potent AAD for preventing AF recurrence. It has both Class I and III effects and is often used to facilitate repeat electrical cardioversion in refractory patients.8,13–15 Despite its efficacy, amiodarone has been associated with adverse side effects (e.g. gastrointestinal bleeding, hypothyroidism, and vision changes) in up to 15% of patients within the first year.16,17

Our objective was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs comparing the impact of treatment with amiodarone vs. no therapy on restoration and maintenance of sinus rhythm in patients with AF who are undergoing elective electrical cardioversion.

Methods

In a prespecified protocol, we outlined our search strategy, our criteria for study selection, our statistical methodology, and our approach to evaluating the risk of bias and grading the evidence (PROSPERO 2017: CRD42017068877).

Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE from inception to July 2018 using a search strategy designed with input from a research librarian (see Supplementary material online, Appendix Figure D). We also searched clinicaltrials.gov and WHO ICTRP for ongoing or completed, but unpublished, trials, and reviewed the conference proceedings of the last two meetings of the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and European Society of Cardiology. Finally, we consulted experts on the topic to see if they were aware of other relevant studies.

Eligibility criteria

We included RCTs conducted on humans. We did not place any language constraints. Our population of interest was adult patients with AF (or atrial flutter) of any duration undergoing elective electrical cardioversion of any type to restore sinus rhythm. The intervention was treatment with amiodarone, and the comparator was no treatment (i.e. placebo or no intervention). Our outcomes of interest were (i) restoration of sinus rhythm, (ii) maintenance during follow-up, and (iii) adverse side effects before, during, and after cardioversion.

Study selection

We uploaded all titles and abstracts from the electronic search into RefWorks (ProQuest, United States), then Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Australia). Two reviewers independently performed title and abstract screening, and full-text eligibility assessment. We resolved conflicts by consensus.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Independently and in duplicate, we used predefined data forms to extract descriptive data from included studies. Whenever possible, we applied intention-to-treat analysis using the number of participants randomized to a study arm as the total denominator. We assumed the worst-case scenario—i.e. no longer in sinus rhythm—for participants who were lost to follow-up or withdrew for any reason. We also applied an intention-to-cardiovert analysis. Patients who converted to sinus rhythm without electrical cardioversion were evaluated as having successfully cardioverted.

We evaluated the risk of bias for individual studies per outcome with the Cochrane tool.18 We prespecified that open label studies would be at low risk of performance bias if they followed a systematic protocol for electrical cardioversion and administration of additional AADs. We prespecified that blinding would not influence detection bias, as sinus rhythm is an objective outcome. We graded the overall quality of evidence for each outcome with the GRADE framework.19

Statistical analysis

We pooled data using a random effects model in RevMan 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Denmark) because we expected heterogeneity across studies. We presented our pooled results as relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We used the I2 statistic to determine heterogeneity, and predefined significant heterogeneity as I2 > 50%. In our protocol, we outlined a priori the subgroup and sensitivity analyses that we would perform to explore sources of heterogeneity. Our subgroup domains were (i) risk of bias, (ii) duration of pre-treatment, (iii) duration of AF, (iv) protocol for electrical cardioversion, and (v) AAD treatment during follow-up. We assessed publication bias using funnel plot analysis. We also performed a post hoc subgroup analysis of patients who did not convert to sinus rhythm before electrical cardioversion.

For our pooled outcomes, we performed post hoc trial sequential analysis (TSA) to account for type 1 errors due to sparse data and repeated significance testing.20,21 We conducted TSA with an overall 5% risk of type I error and 80% power using TSA Version 0.9.5.5 Beta (Copenhagen Trial Unit, Denmark).

Results

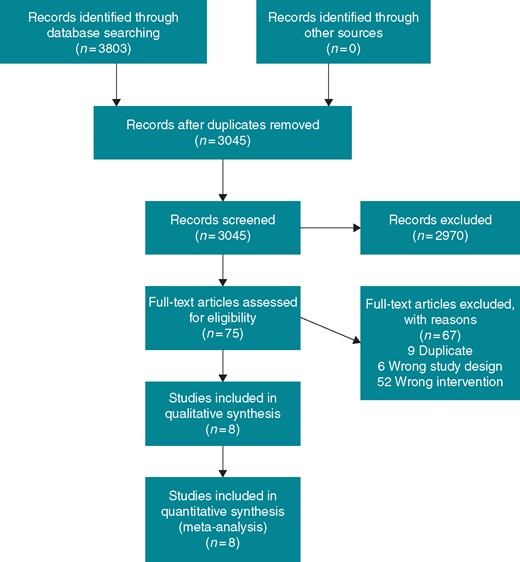

Our search strategy identified 3201 unique references for title and abstract screening. We reviewed the full text of 75 records and included eight studies in our final analysis (Figure 1). During full text screening, we excluded 52 studies for having the wrong intervention which included using amiodarone in all patients or administering amiodarone as an adjunct to other pre-treatment regimens. Characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. The eight RCTs included 1012 participants. The mean age was 65 ± 10 years. The mean duration of AF as reported in six studies was 624 ± 821 days.

| Study . | N . | AF inclusion criteria . | Pre-treatment drug . | Pre-treatment regimen . | Maintenance therapy . | Acute restoration . | Long-term maintenance . | Mean age (years) . | Mean LA diameter (mm) . | Mean duration of AF (days) . | Length of follow-up (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boos et al.22 | 35 | Persistent AF >1 month without a reversible cause | Amiodarone | 200 mg po tid for 1 week | 200 mg po tid for 1 week, 200 mg po bid for 1 week, then 200 mg po od for 1 week | 17/17 (100%) | 8/17 (47%) | 61 ± 12 | 41 ± 8 | 216 ± 126 | 16 ± 4 |

| None | NA | NA | 17/18 (94%) | 3/18 (17%) | 62 ± 8 | 44 ± 6 | 306 ± 180 | ||||

| Channer et al.23 | 161 | Sustained AF >72 h without a reversible cause | Amiodarone | 400 mg po bid for 2 weeks | 200 mg po od for 8 weeks | 48/62 (77%) | 21/62 (34%) | 65 ± 10 | 44 ± 7 | 180 (30–2820) | 12 |

| Amiodarone | 400 mg po bid for 2 weeks | 200 mg po od for 52 weeks | 48/61 (79%) | 30/61 (49%) | 66 ± 10 | 44 ± 7 | 180 (30–5400) | ||||

| Placebo | NA | NA | 30/38 (79%) | 2/38 (5%) | 68 ± 8 | 44 ± 7 | 150 (30–2520) | ||||

| Galperin et al.24 | 95 | Chronic AF >2 months | Amiodarone | 600 mg po od for 4 weeks | 200 mg po od for remainder of study | 35/47 (74%) | 22/47 (47%) | 62 ± 8 | 47 ± 7 | 1072 ± 1523 | 16 ± 10 |

| Placebo | NA | NA | 15/48 (31%) | 3/48 (6%) | 65 ± 6 | 48 ± 7 | 1066 ± 992 | ||||

| Jong et al.30 | 87 | Chronic AF >6 months | Amiodarone | 200 mg po tid for 4 weeks | 200 mg po od for 1 month, then 200 mg po qad for 1 month | 39/48 (81%) | NA | 63 ± 12 | 51 ± 13 | 540 ± 360 | 2 |

| Placebo | NA | NA | 25/43 (58%) | 62 ± 11 | 50 ± 12 | 570 ± 300 | |||||

| Kanoupakis et al.26 | 94 | Persistent AF >7 days | Amiodarone | 600 mg po for 2 weeks, then 200 mg po for 2 weeks | 200 mg po od for remainder of study | 44/48 (92%) | NA | 64 ± 8 | 45 ± 4 | 300 ± 360 | 1 |

| Placebo | NA | NA | 32/47 (68%) | 61 ± 10 | 43 ± 4 | 390 ± 510 | |||||

| Manios et al.27 | 71 | Persistent AF >3 months | Amiodarone | 600 mg po for 2 weeks, then 200 mg po for 4 weeks | 200 mg po od for 6 weeks | 31/36 (86%) | NA | 66 ± 7 | 44 ± 6 | 1050 ± 870 | 1.5 |

| None | NA | NA | 26/37 (70%) | 62 ± 11 | 43 ± 4 | 960 ± 1020 | |||||

| Singh et al.28 | 404 | Persistent AF >72 h | Amiodarone | 800 mg po for 2 weeks, then 600 mg po for 2 weeks | 160 mg po od for remainder of study | 206/237 (77%) | 134/267 (50%) | 67 ± 9 | 49 ± 7 | NA | 12 |

| Placebo | NA | NA | 90/137 (66%) | 17/137 (12%) | 68 ± 10 | 48 ± 7 | |||||

| Vijayalakshmi et al.29 | 58 | AF <1 year | Amiodarone | 600 mg po for 1 week, 400 mg po for 1 week, then 200 mg po for 4 weeks | NA | 22/27 (81%) | NA | 66 ± 11 | 43 ± 7 | 198 ± 117 | 6 |

| None | NA | NA | 23/31 (74%) | 65 ± 9 | 42 ± 7 | 210 ± 120 |

| Study . | N . | AF inclusion criteria . | Pre-treatment drug . | Pre-treatment regimen . | Maintenance therapy . | Acute restoration . | Long-term maintenance . | Mean age (years) . | Mean LA diameter (mm) . | Mean duration of AF (days) . | Length of follow-up (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boos et al.22 | 35 | Persistent AF >1 month without a reversible cause | Amiodarone | 200 mg po tid for 1 week | 200 mg po tid for 1 week, 200 mg po bid for 1 week, then 200 mg po od for 1 week | 17/17 (100%) | 8/17 (47%) | 61 ± 12 | 41 ± 8 | 216 ± 126 | 16 ± 4 |

| None | NA | NA | 17/18 (94%) | 3/18 (17%) | 62 ± 8 | 44 ± 6 | 306 ± 180 | ||||

| Channer et al.23 | 161 | Sustained AF >72 h without a reversible cause | Amiodarone | 400 mg po bid for 2 weeks | 200 mg po od for 8 weeks | 48/62 (77%) | 21/62 (34%) | 65 ± 10 | 44 ± 7 | 180 (30–2820) | 12 |

| Amiodarone | 400 mg po bid for 2 weeks | 200 mg po od for 52 weeks | 48/61 (79%) | 30/61 (49%) | 66 ± 10 | 44 ± 7 | 180 (30–5400) | ||||

| Placebo | NA | NA | 30/38 (79%) | 2/38 (5%) | 68 ± 8 | 44 ± 7 | 150 (30–2520) | ||||

| Galperin et al.24 | 95 | Chronic AF >2 months | Amiodarone | 600 mg po od for 4 weeks | 200 mg po od for remainder of study | 35/47 (74%) | 22/47 (47%) | 62 ± 8 | 47 ± 7 | 1072 ± 1523 | 16 ± 10 |

| Placebo | NA | NA | 15/48 (31%) | 3/48 (6%) | 65 ± 6 | 48 ± 7 | 1066 ± 992 | ||||

| Jong et al.30 | 87 | Chronic AF >6 months | Amiodarone | 200 mg po tid for 4 weeks | 200 mg po od for 1 month, then 200 mg po qad for 1 month | 39/48 (81%) | NA | 63 ± 12 | 51 ± 13 | 540 ± 360 | 2 |

| Placebo | NA | NA | 25/43 (58%) | 62 ± 11 | 50 ± 12 | 570 ± 300 | |||||

| Kanoupakis et al.26 | 94 | Persistent AF >7 days | Amiodarone | 600 mg po for 2 weeks, then 200 mg po for 2 weeks | 200 mg po od for remainder of study | 44/48 (92%) | NA | 64 ± 8 | 45 ± 4 | 300 ± 360 | 1 |

| Placebo | NA | NA | 32/47 (68%) | 61 ± 10 | 43 ± 4 | 390 ± 510 | |||||

| Manios et al.27 | 71 | Persistent AF >3 months | Amiodarone | 600 mg po for 2 weeks, then 200 mg po for 4 weeks | 200 mg po od for 6 weeks | 31/36 (86%) | NA | 66 ± 7 | 44 ± 6 | 1050 ± 870 | 1.5 |

| None | NA | NA | 26/37 (70%) | 62 ± 11 | 43 ± 4 | 960 ± 1020 | |||||

| Singh et al.28 | 404 | Persistent AF >72 h | Amiodarone | 800 mg po for 2 weeks, then 600 mg po for 2 weeks | 160 mg po od for remainder of study | 206/237 (77%) | 134/267 (50%) | 67 ± 9 | 49 ± 7 | NA | 12 |

| Placebo | NA | NA | 90/137 (66%) | 17/137 (12%) | 68 ± 10 | 48 ± 7 | |||||

| Vijayalakshmi et al.29 | 58 | AF <1 year | Amiodarone | 600 mg po for 1 week, 400 mg po for 1 week, then 200 mg po for 4 weeks | NA | 22/27 (81%) | NA | 66 ± 11 | 43 ± 7 | 198 ± 117 | 6 |

| None | NA | NA | 23/31 (74%) | 65 ± 9 | 42 ± 7 | 210 ± 120 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; LA, left atrium; NA, not applicable.

| Study . | N . | AF inclusion criteria . | Pre-treatment drug . | Pre-treatment regimen . | Maintenance therapy . | Acute restoration . | Long-term maintenance . | Mean age (years) . | Mean LA diameter (mm) . | Mean duration of AF (days) . | Length of follow-up (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boos et al.22 | 35 | Persistent AF >1 month without a reversible cause | Amiodarone | 200 mg po tid for 1 week | 200 mg po tid for 1 week, 200 mg po bid for 1 week, then 200 mg po od for 1 week | 17/17 (100%) | 8/17 (47%) | 61 ± 12 | 41 ± 8 | 216 ± 126 | 16 ± 4 |

| None | NA | NA | 17/18 (94%) | 3/18 (17%) | 62 ± 8 | 44 ± 6 | 306 ± 180 | ||||

| Channer et al.23 | 161 | Sustained AF >72 h without a reversible cause | Amiodarone | 400 mg po bid for 2 weeks | 200 mg po od for 8 weeks | 48/62 (77%) | 21/62 (34%) | 65 ± 10 | 44 ± 7 | 180 (30–2820) | 12 |

| Amiodarone | 400 mg po bid for 2 weeks | 200 mg po od for 52 weeks | 48/61 (79%) | 30/61 (49%) | 66 ± 10 | 44 ± 7 | 180 (30–5400) | ||||

| Placebo | NA | NA | 30/38 (79%) | 2/38 (5%) | 68 ± 8 | 44 ± 7 | 150 (30–2520) | ||||

| Galperin et al.24 | 95 | Chronic AF >2 months | Amiodarone | 600 mg po od for 4 weeks | 200 mg po od for remainder of study | 35/47 (74%) | 22/47 (47%) | 62 ± 8 | 47 ± 7 | 1072 ± 1523 | 16 ± 10 |

| Placebo | NA | NA | 15/48 (31%) | 3/48 (6%) | 65 ± 6 | 48 ± 7 | 1066 ± 992 | ||||

| Jong et al.30 | 87 | Chronic AF >6 months | Amiodarone | 200 mg po tid for 4 weeks | 200 mg po od for 1 month, then 200 mg po qad for 1 month | 39/48 (81%) | NA | 63 ± 12 | 51 ± 13 | 540 ± 360 | 2 |

| Placebo | NA | NA | 25/43 (58%) | 62 ± 11 | 50 ± 12 | 570 ± 300 | |||||

| Kanoupakis et al.26 | 94 | Persistent AF >7 days | Amiodarone | 600 mg po for 2 weeks, then 200 mg po for 2 weeks | 200 mg po od for remainder of study | 44/48 (92%) | NA | 64 ± 8 | 45 ± 4 | 300 ± 360 | 1 |

| Placebo | NA | NA | 32/47 (68%) | 61 ± 10 | 43 ± 4 | 390 ± 510 | |||||

| Manios et al.27 | 71 | Persistent AF >3 months | Amiodarone | 600 mg po for 2 weeks, then 200 mg po for 4 weeks | 200 mg po od for 6 weeks | 31/36 (86%) | NA | 66 ± 7 | 44 ± 6 | 1050 ± 870 | 1.5 |

| None | NA | NA | 26/37 (70%) | 62 ± 11 | 43 ± 4 | 960 ± 1020 | |||||

| Singh et al.28 | 404 | Persistent AF >72 h | Amiodarone | 800 mg po for 2 weeks, then 600 mg po for 2 weeks | 160 mg po od for remainder of study | 206/237 (77%) | 134/267 (50%) | 67 ± 9 | 49 ± 7 | NA | 12 |

| Placebo | NA | NA | 90/137 (66%) | 17/137 (12%) | 68 ± 10 | 48 ± 7 | |||||

| Vijayalakshmi et al.29 | 58 | AF <1 year | Amiodarone | 600 mg po for 1 week, 400 mg po for 1 week, then 200 mg po for 4 weeks | NA | 22/27 (81%) | NA | 66 ± 11 | 43 ± 7 | 198 ± 117 | 6 |

| None | NA | NA | 23/31 (74%) | 65 ± 9 | 42 ± 7 | 210 ± 120 |

| Study . | N . | AF inclusion criteria . | Pre-treatment drug . | Pre-treatment regimen . | Maintenance therapy . | Acute restoration . | Long-term maintenance . | Mean age (years) . | Mean LA diameter (mm) . | Mean duration of AF (days) . | Length of follow-up (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boos et al.22 | 35 | Persistent AF >1 month without a reversible cause | Amiodarone | 200 mg po tid for 1 week | 200 mg po tid for 1 week, 200 mg po bid for 1 week, then 200 mg po od for 1 week | 17/17 (100%) | 8/17 (47%) | 61 ± 12 | 41 ± 8 | 216 ± 126 | 16 ± 4 |

| None | NA | NA | 17/18 (94%) | 3/18 (17%) | 62 ± 8 | 44 ± 6 | 306 ± 180 | ||||

| Channer et al.23 | 161 | Sustained AF >72 h without a reversible cause | Amiodarone | 400 mg po bid for 2 weeks | 200 mg po od for 8 weeks | 48/62 (77%) | 21/62 (34%) | 65 ± 10 | 44 ± 7 | 180 (30–2820) | 12 |

| Amiodarone | 400 mg po bid for 2 weeks | 200 mg po od for 52 weeks | 48/61 (79%) | 30/61 (49%) | 66 ± 10 | 44 ± 7 | 180 (30–5400) | ||||

| Placebo | NA | NA | 30/38 (79%) | 2/38 (5%) | 68 ± 8 | 44 ± 7 | 150 (30–2520) | ||||

| Galperin et al.24 | 95 | Chronic AF >2 months | Amiodarone | 600 mg po od for 4 weeks | 200 mg po od for remainder of study | 35/47 (74%) | 22/47 (47%) | 62 ± 8 | 47 ± 7 | 1072 ± 1523 | 16 ± 10 |

| Placebo | NA | NA | 15/48 (31%) | 3/48 (6%) | 65 ± 6 | 48 ± 7 | 1066 ± 992 | ||||

| Jong et al.30 | 87 | Chronic AF >6 months | Amiodarone | 200 mg po tid for 4 weeks | 200 mg po od for 1 month, then 200 mg po qad for 1 month | 39/48 (81%) | NA | 63 ± 12 | 51 ± 13 | 540 ± 360 | 2 |

| Placebo | NA | NA | 25/43 (58%) | 62 ± 11 | 50 ± 12 | 570 ± 300 | |||||

| Kanoupakis et al.26 | 94 | Persistent AF >7 days | Amiodarone | 600 mg po for 2 weeks, then 200 mg po for 2 weeks | 200 mg po od for remainder of study | 44/48 (92%) | NA | 64 ± 8 | 45 ± 4 | 300 ± 360 | 1 |

| Placebo | NA | NA | 32/47 (68%) | 61 ± 10 | 43 ± 4 | 390 ± 510 | |||||

| Manios et al.27 | 71 | Persistent AF >3 months | Amiodarone | 600 mg po for 2 weeks, then 200 mg po for 4 weeks | 200 mg po od for 6 weeks | 31/36 (86%) | NA | 66 ± 7 | 44 ± 6 | 1050 ± 870 | 1.5 |

| None | NA | NA | 26/37 (70%) | 62 ± 11 | 43 ± 4 | 960 ± 1020 | |||||

| Singh et al.28 | 404 | Persistent AF >72 h | Amiodarone | 800 mg po for 2 weeks, then 600 mg po for 2 weeks | 160 mg po od for remainder of study | 206/237 (77%) | 134/267 (50%) | 67 ± 9 | 49 ± 7 | NA | 12 |

| Placebo | NA | NA | 90/137 (66%) | 17/137 (12%) | 68 ± 10 | 48 ± 7 | |||||

| Vijayalakshmi et al.29 | 58 | AF <1 year | Amiodarone | 600 mg po for 1 week, 400 mg po for 1 week, then 200 mg po for 4 weeks | NA | 22/27 (81%) | NA | 66 ± 11 | 43 ± 7 | 198 ± 117 | 6 |

| None | NA | NA | 23/31 (74%) | 65 ± 9 | 42 ± 7 | 210 ± 120 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; LA, left atrium; NA, not applicable.

Pre-treatment, cardioversion protocol, and maintenance therapy

The pre-treatment duration ranged from 1 week to 6 weeks.22–29 The most frequent dose was 600 mg per day in divided doses. Five studies administered placebo.23,24,26,28,30 All studies included a protocol for electrical cardioversion. The number of shocks ranged from 3 to 6, and two studies performed internal cardioversion exclusively.

Of the four studies with more than 1-year follow-up, two administered amiodarone to the intervention arm for the remainder of the study after electrical cardioversion.24,28 Boos et al.22 administered amiodarone for 3 weeks after electrical cardioversion. Channer et al.23 pre-treated two arms with amiodarone, and continued it for 8 weeks in one arm and 52 weeks in the other; the placebo group received placebo throughout the study.

Risk of bias

We present our risk of bias assessment in Figure 2. For acute restoration of sinus rhythm, we judged three RCTs to be at low risk of bias.26–28 We evaluated two studies as having a high risk of selection bias due to inadequate allocation concealment.23,29 Because Channer et al.23 only reported per-protocol numbers, we also judged it to be at high risk of attrition bias. Three RCTs were rated as having an unclear risk of selection bias because they did not describe their randomization practices.22,24,30 For long-term maintenance of sinus rhythm, we rated Boos et al.22 as having a high risk of performance and detection biases because of its open-label design.

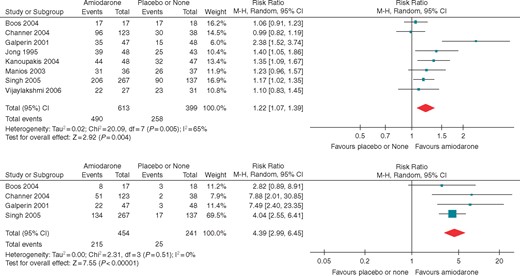

Forest plots for (A) acute restoration and (B) long-term maintenance of sinus rhythm.

Acute restoration of sinus rhythm

Eight RCTs (1012 participants, 748 events) reported data on acute restoration of sinus rhythm (Figure 2). Compared with patients who were not pre-treated, pre-treated patients were more likely to convert to sinus rhythm (RR 1.22, CI 1.07–1.39, n = 1012, I2 = 65%). Absolute restoration rates were 80% and 65%, respectively, for pre-treatment and no pre-treatment. In absolute effects, pre-treatment with amiodarone would restore sinus rhythm in 142 more patients per 1000 patients (CI 45 more, 252 more). We judged the overall evidence to be of high quality.

In our first sensitivity analysis (see Supplementary material online, Appendix), when we excluded the five studies at unclear or high risk of bias, the estimate of effect was unchanged (RR 1.22, CI 1.10–1.36, P < 0.001, n = 572, I2 = 0%). In our second sensitivity analysis, we considered patients with different pre-treatment durations (4 weeks or more vs. less than 4 weeks) separately. Patients who were pre-treated for at least 4 weeks were more likely to convert to sinus rhythm (RR 1.31, CI 1.13–1.51, P < 0.001, n = 816, I2 = 54%), while pre-treatment for less than 4 weeks had no effect on this outcome (RR 1.03, CI 0.91–1.16, P = 0.64, n = 196, I2 = 65). Both AF duration (P = 0.09, n = 608, I2 = 65%) and number of shocks in the cardioversion protocol (P = 0.13, n = 1012, I2 = 57%) did not explain the differences in results among studies.

Post hoc analysis of electrical cardioversion excluding spontaneous conversion

In the subgroup of patients who did not convert to sinus rhythm in the pre-treatment period and underwent electrical cardioversion, absolute restoration rates were 77% and 67%, respectively, for pre-treatment and no pre-treatment. Pre-treated patients were more likely to undergo a successful electrical cardioversion (RR 1.15, CI 1.02–1.30, P = 0.03, n = 840, I2 = 59%).

We assessed the overall quality of evidence for pooled outcomes using GRADE (see Supplementary material online, Appendix Table C). For restoration of sinus rhythm, we did not evaluate the inconsistency of studies to be serious. Although there was significant heterogeneity (I2 = 65%), moderate and very large effects in the same direction were responsible for the inconsistency between studies.31

Long-term maintenance of sinus rhythm

Follow-up was longer than 1 year in four RCTs (mean 13 ± 4 months). The RR of remaining in sinus rhythm was 4.39 (CI 2.99–6.45, P < 0.001, n = 695, I2 = 0%) for treated patients when compared with controls (Figure 2). Forty-seven percent of treated patients remained in sinus rhythm vs. 10% of controls. In absolute effects, sinus rhythm would be maintained in 352 more patients per 1000 patients treated with amiodarone (CI 206 more, 565 more).

When we assessed the quality of evidence for long-term maintenance, we did not consider the overall risk of bias to be serious because a low risk of bias study contributed the majority of the weight to the point estimate (70%). We judged the overall quality of evidence to be high.

Trial sequential analysis

Sensitivity analyses using TSA supported our results (see Supplementary material online, Appendix Figure C). According to TSA, the positive outcome of acute restoration of sinus rhythm had a pooled RR of 1.21 (CI 1.07–1.36, P = 0.0022, n = 1012, D2 = 70%). Maintenance of sinus rhythm at 1-year follow-up demonstrated a pooled RR of 4.39 (CI 2.99–6.45, P < 0.001, n = 695, D2 = 0%) using the lower-bound CI benefit increase of 1.99. For both outcomes, the cumulative z-curve crossed the boundary for benefit at the respective required information sizes. This increases our confidence regarding the positive impact of amiodarone vs. no treatment on these outcomes.

Adverse effects

Due to variable reporting, we were unable to pool data on adverse effects (Table 2). Four studies reported adverse effects from the pre-treatment period.22,27,29,30 There were six events (one each of hypothyroidism, gastrointestinal upset, skin photo-allergy, dizziness, sleeping disturbance, and sunburn) in the amiodarone arm, and one non-cardiac death among controls (see Supplementary material online, Appendix Table B). On the day of cardioversion, amiodarone-treated participants experienced more adverse side effects (based on three studies). Only one adverse side effect—an episode of junctional rhythm in the amiodarone arm—failed to resolve spontaneously. Three studies reported adverse effects but did not specify their timing. Singh et al.28 reported no statistically significant difference in the incidence of major bleeding, stroke, and death.

| Pre-treatment drug . | Number of studies . | N . | Adverse effects (n) . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-cardioversion | ||||

| Amiodarone | 4 | 128a | Hypothyroidism (1) | Dizziness (1) |

| Gastrointestinal irritation (1) | Sleeping disturbance (1) | |||

| Skin photoallergy (1) | Sunburn (1) | |||

| Total (6) | ||||

| None | 4 | 129 | Non-cardiac death (1) | Total (1) |

| Peri-cardioversionb | ||||

| Amiodarone | 3 | 92 | Transient sinus arrest (1) | First-degree AV block (10) |

| Sinus bradycardia (20) | Hypotension (1) | |||

| Junctional rhythm (2) | Total (34) | |||

| None | 3 | 92 | Transient sinus arrest (1) | Sinus bradycardia (5) |

| Total (6) | ||||

| Pre-treatment drug . | Number of studies . | N . | Adverse effects (n) . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-cardioversion | ||||

| Amiodarone | 4 | 128a | Hypothyroidism (1) | Dizziness (1) |

| Gastrointestinal irritation (1) | Sleeping disturbance (1) | |||

| Skin photoallergy (1) | Sunburn (1) | |||

| Total (6) | ||||

| None | 4 | 129 | Non-cardiac death (1) | Total (1) |

| Peri-cardioversionb | ||||

| Amiodarone | 3 | 92 | Transient sinus arrest (1) | First-degree AV block (10) |

| Sinus bradycardia (20) | Hypotension (1) | |||

| Junctional rhythm (2) | Total (34) | |||

| None | 3 | 92 | Transient sinus arrest (1) | Sinus bradycardia (5) |

| Total (6) | ||||

Singh et al. (not included in this table) reported that there was no statistically significant difference in adverse effects.

Jong et al. withdrew four patients in the amiodarone arm due to the reported adverse effects. These patients are included in this table.

Only one adverse effect (episode of junctional rhythm) required intervention.

| Pre-treatment drug . | Number of studies . | N . | Adverse effects (n) . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-cardioversion | ||||

| Amiodarone | 4 | 128a | Hypothyroidism (1) | Dizziness (1) |

| Gastrointestinal irritation (1) | Sleeping disturbance (1) | |||

| Skin photoallergy (1) | Sunburn (1) | |||

| Total (6) | ||||

| None | 4 | 129 | Non-cardiac death (1) | Total (1) |

| Peri-cardioversionb | ||||

| Amiodarone | 3 | 92 | Transient sinus arrest (1) | First-degree AV block (10) |

| Sinus bradycardia (20) | Hypotension (1) | |||

| Junctional rhythm (2) | Total (34) | |||

| None | 3 | 92 | Transient sinus arrest (1) | Sinus bradycardia (5) |

| Total (6) | ||||

| Pre-treatment drug . | Number of studies . | N . | Adverse effects (n) . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-cardioversion | ||||

| Amiodarone | 4 | 128a | Hypothyroidism (1) | Dizziness (1) |

| Gastrointestinal irritation (1) | Sleeping disturbance (1) | |||

| Skin photoallergy (1) | Sunburn (1) | |||

| Total (6) | ||||

| None | 4 | 129 | Non-cardiac death (1) | Total (1) |

| Peri-cardioversionb | ||||

| Amiodarone | 3 | 92 | Transient sinus arrest (1) | First-degree AV block (10) |

| Sinus bradycardia (20) | Hypotension (1) | |||

| Junctional rhythm (2) | Total (34) | |||

| None | 3 | 92 | Transient sinus arrest (1) | Sinus bradycardia (5) |

| Total (6) | ||||

Singh et al. (not included in this table) reported that there was no statistically significant difference in adverse effects.

Jong et al. withdrew four patients in the amiodarone arm due to the reported adverse effects. These patients are included in this table.

Only one adverse effect (episode of junctional rhythm) required intervention.

Discussion

For patients with persistent AF, high-quality evidence supports that treatment with amiodarone increases both the acute restoration and long-term maintenance of sinus rhythm. Amiodarone treatment is associated with minor side effects only before and immediately after electrical cardioversion. Although included studies did not report an increase in major adverse effects over longer follow-up, we were unable to meta-analyse data for this outcome, and no definitive conclusion can be made regarding adverse effects during mid- to long-term follow-up. In summary, treatment with amiodarone is associated with few adverse side effects in the pre- and peri-cardioversion period that can greatly reduce the burden of AF for patients who pursue rhythm control (i.e. four-fold increased chance of remaining in sinus rhythm over 13 months).

This evidence for the efficacy of amiodarone pre-treatment prior to cardioversion has not been translated into contemporary practice. Among patients enrolled in the international RHYTHM-AF registry, 1931 underwent electrical cardioversion.32 Although amiodarone pre-treatment was independently associated with obtaining and maintaining sinus rhythm (odds ratio 1.56 95% CI 1.04–2.33), only 16.8% of patients received amiodarone prior to cardioversion. Similarly, of the 1504 patients enrolled from 16 countries in the X-VeRT trial, only 18.6% were being treated with amiodarone before electrical cardioversion.4 Failure of knowledge translation, early recourse to AF ablation, or fear of amiodarone-related adverse events are all possible causes of this disconnect.

One of the key barriers to the adoption of research findings into clinical practice is difficulty identifying the current best evidence.33 Amongst the prominent societies’ latest guidelines on the management of AF, the ESC is the only society to recommend anti-arrhythmic agent pre-treatment prior to electrical cardioversion.12,34,35 This may be explained by the absence of formal synthesis of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of amiodarone pre-treatment before this meta-analysis. The attractive option to refer patients for a more definitive pulmonary vein isolation may also have distracted clinicians from anti-arrhythmic pre-treatment; this does not mean, however, that amiodarone pre-treatment is outdated. Physicians often use electrical cardioversion to confirm that rhythm control improves symptoms. Pre-treating such patients with amiodarone prior to cardioversion may help identify patients who will derive the most symptomatic benefit from AF ablation. Furthermore, continuing amiodarone in these patients could maximize their time in sinus rhythm until the procedure. This strategy may be particularly useful in Canada, where median wait times for AF ablation can approach 10 months.36

Clinicians could be hesitant to expose patients—particularly those who are young—with persistent AF to amiodarone-related adverse effects. In some case series, the incidence of adverse effects after a year of amiodarone treatment reached 19%.37,38 However, in our review, the incidence of adverse outcomes was much lower than previously reported—reassuring for the safety of amiodarone pre-treatment. Short-term pre-treatment may have less toxicity; however, given the relatively short follow-up in the included trials, our results do not inform on the incidence of long-term adverse effects in this patients population. Another previously reported concern with amiodarone treatment was the theoretical increase in defibrillation threshold.39,40 The significant increase in conversion to sinus rhythm after electrical cardioversion with amiodarone pre-treatment in this review provides indirect evidence of the safety of defibrillation thresholds in amiodarone-treated patients.

Our systematic review informs clinical and research practice in several ways. First, we identify the high-quality evidence that exists for pre-treating patients with amiodarone. Our study obviates the need for further clinical studies and should be used to inform guidelines. Second, we identify the potential clinical benefits of pre-treatment: (i) decrease in further healthcare resource utilization (e.g. repeat electrical cardioversion, AF ablation), (ii) reduction in number of symptomatic patients who abandon a rhythm control strategy, and (iii) improved quality of life during the waiting period for symptomatic patients who undergo AF ablation. Finally, although clinical trials in the past have indicated an increase in the defibrillation threshold with amiodarone, we demonstrate how pre-treatment improves the clinical efficacy of cardioversion for AF.41

Strengths and limitations

Our systematic review and meta-analysis has several strengths. First, it is the first study to systematically summarize the evidence surrounding pre-treatment with amiodarone for electrical cardioversion of AF. We conducted a comprehensive search that was not restricted by language and followed a rigorous protocol that outlined our statistical methods and subgroup analyses a priori. Second, our results are a conservative estimate. We performed intention-to-treat and intention-to-cardiovert analyses and assumed the worst-case scenario for missing data and participants. Furthermore, we assessed the quality of each included study separately for each pooled outcome. Finally, we applied the GRADE framework to evaluate the quality of the evidence and used TSA to assess the statistical reliability of our results.

We applied study-specific definitions for AF and cardioversion success. Variability in these definitions may explain the heterogeneity we observed for the acute restoration of sinus rhythm. More than half of the patients included in our analysis were from studies that enrolled patients if AF lasted at least 72 h.23,28 Paroxysmal AF is more prone to cardioversion and may have a better long-term outcome. However, such a consideration should not affect the relative increase in sinus rhythm restoration and maintenance. Furthermore, the most recent study included in our analysis is from 2006. The demographic of patients undergoing cardioversion is likely to have changed since then. In contemporary patients, previous ablation may be more prevalent. Although the studies included in our systematic review did not report a statistically significant increase in adverse side effects, we were unable to meta-analyse the data for this outcome. Given concerns associated with the long-term toxicity of amiodarone, other AADs may provide similar benefits with fewer adverse effects. Singh et al.’s comparison of amiodarone and sotalol, however, suggests that the antiarrhythmic benefits of amiodarone may be superior to other medications. Indeed, a network meta-analysis comparing the different antiarrhythmic medications is required to know which agent should be favoured. In addition, the mean follow-up (i.e. 13 months) for maintenance of sinus rhythm was relatively short. Despite this short follow-up, the absolute success rate of sinus rhythm maintenance remains poor (<50%). Furthermore, except for Singh et al., the studies included in our analysis were single-centre. Nonetheless, the TSA indicates that the number of trials and participants were sufficient to determine an accurate estimate of effect. Finally, as with all meta-analyses, there is a risk of publication bias with positive trials being more likely to be published in the literature. Given the number of trials included in our meta-analysis, visual and statistical assessment for publication bias were impossible.

Conclusions

In summary, in AF patients who undergo electrical cardioversion, pre-treatment with amiodarone significantly improves both acute restoration and maintenance of sinus rhythm during more than 1-year follow-up. Adverse side effects were uncommon and not serious before and during electrical cardioversion. Given the high rate of AF recurrence following cardioversion, clinicians should consider greater use amiodarone for 1–6 weeks before electrical cardioversion.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Laura Banfield for refining our search strategy. We would also like to acknowledge Serena Sibilio, Cathevine Yang, and Alexandra Sibiga for their translation of Italian, Chinese, and Polish. The authors (W.F.M. and K.J.U.) are members of the Cardiac Arrhythmia Network of Canada (CANet) HQP Association for Trainees (CHAT).

Funding

This work was supported by a Mach-Gaensslen Medical Summer Student Research Grant [2017], McMaster University Department of Medicine Medical Student Research Award [2017], McMaster Medical Student Research Excellence Scholarship [2018], and Heart and Stroke Foundation Ontario Evelyn McGloin Summer Medical Student Scholarship [2018].

Conflict of interest: none declared.