-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nikolaos Papageorgiou, Rui Providência, Konstantinos Bronis, Dirk G Dechering, Neil Srinivasan, Lars Eckardt, Pier D Lambiase, Catheter ablation for ventricular tachycardia in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis: a systematic review, EP Europace, Volume 20, Issue 4, April 2018, Pages 682–691, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eux077

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) is associated with a poor prognosis. Important features of CS include heart failure, conduction abnormalities, and ventricular arrhythmias. Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is often refractory to antiarrhythmic drugs (AAD) and immunosuppression. Catheter ablation has emerged as a treatment option for recurrent VT. However, data on the efficacy and outcomes of VT ablation in this context are sparse.

A systematic search was performed on PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane database (from inception to September 2016) with included studies providing a minimum of information on CS patients undergoing VT ablation: age, gender, VT cycle length, CS diagnosis criteria, and baseline medications. Five studies reporting on 83 patients were identified. The mean age of patients was 50 ± 8 years, 53/30 (males/females) with a maximum of 56 patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy, mean ejection fraction was 39.1 ± 3.1% and 94% had an implantable cardioverter defibrillator in situ. The median number of VTs was 3 (2.6–4.9)/patient, mean cycle length of 360 ms (326–400 ms). Hundred percent of VTs received endocardial ablation, and 18% required epicardial ablation. The complication rates were 4.7–6.3%. Relapse occurred in 45 (54.2%) patients with an incidence of relapse 0.33 (95% confidence interval 0.108–0.551, P < 0.004). Employing a less stringent endpoint (i.e. freedom from arrhythmia or reduction of ventricular arrhythmia burden), 61 (88.4%) patients improved following ablation.

These data support the utilization of catheter ablation in selected CS cases resistant to medical treatment. However, data are derived from observational non-controlled case series, with low-methodological quality. Therefore, future well-designed, randomized controlled trials, or large-scale registries are required.

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous multisystem disease of unknown aetiology.1,2 Apart from the lymph nodes, central nervous system, skin, lungs and eyes, studies have shown that sarcoidosis can also affect the myocardium in about 2–5% of patients.3,4 Cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) is associated with poor prognosis,1–4,5 and its clinical manifestations depend upon the location, extent, and the activity of the disease. The ‘gold triad’ that is normally identified in CS patients is conduction system abnormalities, ventricular arrhythmias, and heart failure.4,6

Ventricular tachycardia (VT)7 is thought to be due to a re-entry mechanism.7,8 However, triggered activity and abnormal automaticity have been observed with CS patients with reduction in arrhythmic burden after initiation of immunosuppression. This makes timing and acute management of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with active inflammation more challenging. Importantly, it is often refractory to antiarrhythmic drugs (AAD) immunosuppression, and frequently requires implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) according to current recommendations.7,8

As recurrent VT is very common in CS and has impact on quality of life and prognosis, studies have investigated possible therapeutic approaches to abolish VT. Catheter ablation has emerged as a treatment option for recurrent VT over the last years.9,10

In this article, we aim to review the available data regarding to the efficacy and safety of VT ablation in patients with CS.

Methods

Study selection

A systematic electronic search was performed on PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane database (from inception to September 2016) with no language limitations, using the following search string: ‘ventricular tachycardia’ AND (‘ablation’ OR ‘catheter ablation’) AND (‘sarcoidosis’ OR ‘sarcoid’).

The population, intervention, comparison and outcome approach was used.11 The population of interest included patients with CS, and the intervention was catheter ablation of VT. In the absence of a control group, a non-controlled observational analysis was performed. The primary outcome measure was VT recurrence post ablation. Procedural success was defined as freedom of VT (at the end of follow-up after a single ablation procedure). Other outcomes included freedom from VT recurrence or reduction of arrhythmia burden; mortality; and heart transplant during follow-up. Assessed procedural complications were procedural death, stroke, cardiac tamponade, acute myocardial infarction, major vascular complications, and ‘other life-threatening complications’, assessed on a study by study basis.

In order to be included, studies needed to provide a minimum of information about the sample of CS patients undergoing catheter ablation of VT, namely age, gender, VT cycle length, and number of morphologies, as well as information on the CS diagnosis criteria, and baseline medication. Observational non-controlled case series required a minimum of five patients to be considered eligible.

Review articles, editorials and case reports, were not considered eligible for the purpose of this review. Patients with granulomatous diseases but without a confirmed diagnosis of sarcoidosis were excluded from the analysis.

Reference lists of all accessed full-text articles were further searched for sources of potentially relevant information. Authors of full-text papers were also contacted by email to retrieve additional information.

Three independent reviewers (NP, RP, and KB) screened all abstracts and titles to identify potentially eligible studies. The full text of these potentially eligible studies was then evaluated. Agreement of at least two reviewers was required for decisions regarding inclusion or exclusion of studies. Study quality was formally evaluated using the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Quality Assessment Tool for Case Series Studies12 three reviewers (NP, RP, and KB). An agreement, between the three reviewers was mandatory for the final classification of studies.

Data extraction and presentation for the preparation of this manuscript followed the recommendations of the PRISMA group.13 The following data were extracted for characterizing each patient sample in the selected studies, whenever available: study design, study population characteristics (age, gender), number and cycle length of VTs, follow-up duration, ablation procedure, definition of relapse, post-procedural monitoring, use of anti-arrhythmic agents. Patient-level data were obtained whenever these were available in the manuscripts or, after contacting authors.

Statistical analysis

Data were pooled using random-effects, according to the Mantel–Haenszel model, through Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (Version 2). Overall incidences and 95% confidence interval (CI) were estimated.

Statistical heterogeneity on each outcome of interest was quantified using the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance. Values of <25, 25–50, and >50% are by convention classified as low, moderate, and high degrees of heterogeneity, respectively.

Results

Study selection and patient characteristics

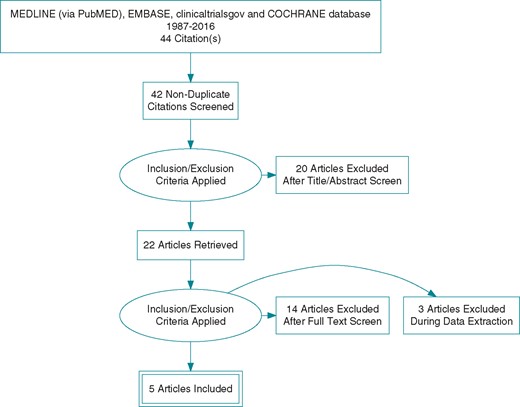

A total of five longitudinal studies meeting the inclusion criteria were identified. The selection process is illustrated in Figure 1 (PRISMA) and a total population of 83 patients with CS undergoing VT ablation were included. The mean age of the patients was 50 ± 8 years, 53/30 (males/females) with 56 receiving immunosuppressive therapy. The mean ejection fraction was 39.1 ± 3.1% and 94% had an ICD in situ (baseline characteristics of patients are presented in Table 1). Overall mean or median number of VTs with which each patient presented per study was in the range of 2.6–4.9 with a mean cycle length in the range of 326–400 ms.

| Study . | Date of procedures/country . | Centres (n) . | Design . | Prospective/retrospective . | CA pts (n) . | Age . | Female gender N (%) . | Mean LVEF (%) . | ICD N (%) . | AADs N (%) . | Immunosuppression N (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jefic 200914 |

| 1 | Case series | Retrospective | 9 | 46.8 | 2 (22.2%) | 42 |

| 9 (100%) | 8 (89.0%)a |

| Deschering 201315 |

| 2 | Case series | Retrospective | 8 | 39.1 | 4 (50%) | 35.6 | 8 (100%) |

| 8 (100%)a |

| Naruse 201416 |

| 1 | Case series | Retrospective | 14 | 60 | 11 (78.6%) | 40 | 12 (85.7%) |

| 12 (85.7%)a |

| Kumar 201510 |

| 1 | Case series | Retrospective | 21 | 47 | 4 (19.0%) | 36 |

| 2.1 ± 0.8 (mean attempted AADs) | 12 (57.1%)a |

| Muser 201617 |

| 1 | Case series | Retrospective | 31 | 55 | 9 (29%) | 42 |

|

|

|

| Study . | Date of procedures/country . | Centres (n) . | Design . | Prospective/retrospective . | CA pts (n) . | Age . | Female gender N (%) . | Mean LVEF (%) . | ICD N (%) . | AADs N (%) . | Immunosuppression N (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jefic 200914 |

| 1 | Case series | Retrospective | 9 | 46.8 | 2 (22.2%) | 42 |

| 9 (100%) | 8 (89.0%)a |

| Deschering 201315 |

| 2 | Case series | Retrospective | 8 | 39.1 | 4 (50%) | 35.6 | 8 (100%) |

| 8 (100%)a |

| Naruse 201416 |

| 1 | Case series | Retrospective | 14 | 60 | 11 (78.6%) | 40 | 12 (85.7%) |

| 12 (85.7%)a |

| Kumar 201510 |

| 1 | Case series | Retrospective | 21 | 47 | 4 (19.0%) | 36 |

| 2.1 ± 0.8 (mean attempted AADs) | 12 (57.1%)a |

| Muser 201617 |

| 1 | Case series | Retrospective | 31 | 55 | 9 (29%) | 42 |

|

|

|

CA, catheter ablation; pts, patients; AADs, antiarrhythmic drugs; US, United States of America; NL, The Netherlands; N, number; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy.

Details on immunosuppression (used agents) were not provided by all studies.

| Study . | Date of procedures/country . | Centres (n) . | Design . | Prospective/retrospective . | CA pts (n) . | Age . | Female gender N (%) . | Mean LVEF (%) . | ICD N (%) . | AADs N (%) . | Immunosuppression N (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jefic 200914 |

| 1 | Case series | Retrospective | 9 | 46.8 | 2 (22.2%) | 42 |

| 9 (100%) | 8 (89.0%)a |

| Deschering 201315 |

| 2 | Case series | Retrospective | 8 | 39.1 | 4 (50%) | 35.6 | 8 (100%) |

| 8 (100%)a |

| Naruse 201416 |

| 1 | Case series | Retrospective | 14 | 60 | 11 (78.6%) | 40 | 12 (85.7%) |

| 12 (85.7%)a |

| Kumar 201510 |

| 1 | Case series | Retrospective | 21 | 47 | 4 (19.0%) | 36 |

| 2.1 ± 0.8 (mean attempted AADs) | 12 (57.1%)a |

| Muser 201617 |

| 1 | Case series | Retrospective | 31 | 55 | 9 (29%) | 42 |

|

|

|

| Study . | Date of procedures/country . | Centres (n) . | Design . | Prospective/retrospective . | CA pts (n) . | Age . | Female gender N (%) . | Mean LVEF (%) . | ICD N (%) . | AADs N (%) . | Immunosuppression N (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jefic 200914 |

| 1 | Case series | Retrospective | 9 | 46.8 | 2 (22.2%) | 42 |

| 9 (100%) | 8 (89.0%)a |

| Deschering 201315 |

| 2 | Case series | Retrospective | 8 | 39.1 | 4 (50%) | 35.6 | 8 (100%) |

| 8 (100%)a |

| Naruse 201416 |

| 1 | Case series | Retrospective | 14 | 60 | 11 (78.6%) | 40 | 12 (85.7%) |

| 12 (85.7%)a |

| Kumar 201510 |

| 1 | Case series | Retrospective | 21 | 47 | 4 (19.0%) | 36 |

| 2.1 ± 0.8 (mean attempted AADs) | 12 (57.1%)a |

| Muser 201617 |

| 1 | Case series | Retrospective | 31 | 55 | 9 (29%) | 42 |

|

|

|

CA, catheter ablation; pts, patients; AADs, antiarrhythmic drugs; US, United States of America; NL, The Netherlands; N, number; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy.

Details on immunosuppression (used agents) were not provided by all studies.

There was an excellent agreement between investigators on the inclusion of the selected studies. Baseline data and the design of selected trials, and diagnostic criteria of CS, are summarized in Table 1 and see Supplementary material online, TableS1, respectively. The diagnosis of CS was based on pathology data or Consensus/Guidelines, which differed slightly across studies (see Supplementary material online, TableS1). Three studies10,14,16 used the Guidelines of the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare,18 while Dechering and colleagues15 based the diagnosis of CS on the combination of pathologic identification of cardiac non-caseating granulomas with clinical findings consistent with cardiac involvement. The most recent study of Muser et al.17 used the criteria of the Heart Rhythm Society. So far, there are no accepted international guidelines for the diagnosis of CS. The two most commonly used guidelines are those of the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare18,and the National Institutes of Health’s A Case Control Etiology of Sarcoidosis Study set of criteria updated in 2014 by the World Association for Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG).19 The most recent guidelines are those of the Heart Rhythm Society.20 All of them are in agreement that the diagnosis of CS can accurately be made only by the presence of non-caseating granuloma on histological examination of myocardial tissue with no alternative cause identified (including negative organismal stains if applicable). In addition, all three include clinical criteria, which are largely similar and could point towards the diagnosis of CS.

The five studies used for the analysis were all retrospective case series. All studies except for one15 were single-centre, and were observational, with no control group.10,14,15–17 According to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Quality Assessment Tool for Case Series Studies12 there is maximum of nine criteria which apply for case series as shown in Supplementary material online, Table 2. Four studies10,15,17 fulfilled eight criteria, while one study14 fulfilled seven criteria.

| Study . | Procedure duration (min) . | Fluoroscopy time (min) . | Mapping system . | Catheters, energy source, power . | Inducible VTs (mean) . | Cycle length of VTs(mean) . | RV/LV mapping% (N) . | Endo/Epimapping% (N) . | Ablation sites% (N) . | VT mapping vs. Substrate mapping . | VT inducibility post-ablation (% of pts) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jefic 200914 | 420 ± 161 | 58 ± 36 | CARTO |

| 4.9 | 348 ms |

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 44.4% (4) still inducible after 1st procedure |

| Deschering 201315 | N/A | N/A | CARTO |

| 3.7 | 326 ms |

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 37.5% (3) still inducible after 1st procedure |

| Naruse 201416 | N/A | N/A | CARTO |

| 2.6 | 400 ms |

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 21% (14) still induciblea after 1st procedure |

| Kumar 201510 | N/A | N/A | CARTO | 4 mm/3.5-mm irrigated tip 25–50 W targeting 10 Ohm | 3 (median) | 355 ms |

| Endo 100% (21)Epi 38.1% (8) |

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 57.1% (12) still inducible after 1st procedure |

| Muser 201617 | 462 ± 156 | 59.9 ± 30.6 | CARTO |

| 3 (median) | 369 ms |

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 10% (3) still inducible after last procedure |

| Mean/Total | 441 | 59 | 100% CARTO | — | 3.7 (mean) |

|

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) |

|

| Study . | Procedure duration (min) . | Fluoroscopy time (min) . | Mapping system . | Catheters, energy source, power . | Inducible VTs (mean) . | Cycle length of VTs(mean) . | RV/LV mapping% (N) . | Endo/Epimapping% (N) . | Ablation sites% (N) . | VT mapping vs. Substrate mapping . | VT inducibility post-ablation (% of pts) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jefic 200914 | 420 ± 161 | 58 ± 36 | CARTO |

| 4.9 | 348 ms |

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 44.4% (4) still inducible after 1st procedure |

| Deschering 201315 | N/A | N/A | CARTO |

| 3.7 | 326 ms |

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 37.5% (3) still inducible after 1st procedure |

| Naruse 201416 | N/A | N/A | CARTO |

| 2.6 | 400 ms |

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 21% (14) still induciblea after 1st procedure |

| Kumar 201510 | N/A | N/A | CARTO | 4 mm/3.5-mm irrigated tip 25–50 W targeting 10 Ohm | 3 (median) | 355 ms |

| Endo 100% (21)Epi 38.1% (8) |

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 57.1% (12) still inducible after 1st procedure |

| Muser 201617 | 462 ± 156 | 59.9 ± 30.6 | CARTO |

| 3 (median) | 369 ms |

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 10% (3) still inducible after last procedure |

| Mean/Total | 441 | 59 | 100% CARTO | — | 3.7 (mean) |

|

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) |

|

RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; N/A, non-available; W, Watt; VT, ventricular tachycardia; N, number; Endo, endocardial; Epi: epicardial.

Percentage provided with regards to total number of inducible VTs (n = 37). Among these, 6 were Purkinje-related.

| Study . | Procedure duration (min) . | Fluoroscopy time (min) . | Mapping system . | Catheters, energy source, power . | Inducible VTs (mean) . | Cycle length of VTs(mean) . | RV/LV mapping% (N) . | Endo/Epimapping% (N) . | Ablation sites% (N) . | VT mapping vs. Substrate mapping . | VT inducibility post-ablation (% of pts) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jefic 200914 | 420 ± 161 | 58 ± 36 | CARTO |

| 4.9 | 348 ms |

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 44.4% (4) still inducible after 1st procedure |

| Deschering 201315 | N/A | N/A | CARTO |

| 3.7 | 326 ms |

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 37.5% (3) still inducible after 1st procedure |

| Naruse 201416 | N/A | N/A | CARTO |

| 2.6 | 400 ms |

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 21% (14) still induciblea after 1st procedure |

| Kumar 201510 | N/A | N/A | CARTO | 4 mm/3.5-mm irrigated tip 25–50 W targeting 10 Ohm | 3 (median) | 355 ms |

| Endo 100% (21)Epi 38.1% (8) |

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 57.1% (12) still inducible after 1st procedure |

| Muser 201617 | 462 ± 156 | 59.9 ± 30.6 | CARTO |

| 3 (median) | 369 ms |

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 10% (3) still inducible after last procedure |

| Mean/Total | 441 | 59 | 100% CARTO | — | 3.7 (mean) |

|

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) |

|

| Study . | Procedure duration (min) . | Fluoroscopy time (min) . | Mapping system . | Catheters, energy source, power . | Inducible VTs (mean) . | Cycle length of VTs(mean) . | RV/LV mapping% (N) . | Endo/Epimapping% (N) . | Ablation sites% (N) . | VT mapping vs. Substrate mapping . | VT inducibility post-ablation (% of pts) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jefic 200914 | 420 ± 161 | 58 ± 36 | CARTO |

| 4.9 | 348 ms |

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 44.4% (4) still inducible after 1st procedure |

| Deschering 201315 | N/A | N/A | CARTO |

| 3.7 | 326 ms |

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 37.5% (3) still inducible after 1st procedure |

| Naruse 201416 | N/A | N/A | CARTO |

| 2.6 | 400 ms |

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 21% (14) still induciblea after 1st procedure |

| Kumar 201510 | N/A | N/A | CARTO | 4 mm/3.5-mm irrigated tip 25–50 W targeting 10 Ohm | 3 (median) | 355 ms |

| Endo 100% (21)Epi 38.1% (8) |

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 57.1% (12) still inducible after 1st procedure |

| Muser 201617 | 462 ± 156 | 59.9 ± 30.6 | CARTO |

| 3 (median) | 369 ms |

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) | 10% (3) still inducible after last procedure |

| Mean/Total | 441 | 59 | 100% CARTO | — | 3.7 (mean) |

|

|

|

| Substrate and VT mapping (if haemodynamically tolerated) |

|

RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; N/A, non-available; W, Watt; VT, ventricular tachycardia; N, number; Endo, endocardial; Epi: epicardial.

Percentage provided with regards to total number of inducible VTs (n = 37). Among these, 6 were Purkinje-related.

Procedural data

Of the five studies included in our analysis, only two studies14,17 reported on the duration of the procedure as well as the mean fluoroscopy time (Table 2). The CARTO mapping system was used in all studies, while a range of 3.5–8 mm irrigated or non-irrigated tip catheters were used for mapping and ablation. Endocardial mapping was performed in all patients, whereas epicardial mapping was performed in 25.3% (21) of patients. Substrate and VT mapping (for haemodynamically tolerated VTs) was performed in all studies.

Catheter ablation was performed using 25–50 W, and three studies10,14,17 targeted an impedance drop of at least 10 Ohm per lesion. Endocardial ablation was performed in all patients (100%), whereas epicardial ablation was performed in 15 patients (18%). Only 70% of patients (15/21) who underwent epicardial mapping were finally ablated from epicardium. All studies checked for inducible VTs at the end of the procedure and at least 1 VT morphology was still inducible in 36 patients (34%). Detailed procedural data are presented in Table 2.

Efficacy of catheter ablation

The mean follow-up period for 3 of the studies14,–16 was 19.6 ± 13.5 months, while the remaining 2 studies10,17 had a median follow-up of 27 months. During the follow-up period, at least 1 episode of recurrent VT occurred in 45 of the 83 (54.2%) patients undergoing catheter ablation. Twenty-six patients required a second ablation procedure, while four patients required a third ablation.

Definition of VT relapse was similar across studies (see Supplementary material online, TableS3). In 3 studies,14,–16 freedom from VT relapse was ≥ 50% after the first ablation procedure. Naruse et al.16 reported the lowest relapse rate (43%) after a single procedure. In this study, 4 patients (28.6%) required a second ablation procedure. Of those 4 patients, 3 patients whose initial ablation was directed at only scar-related VT had recurrence of scar-related VT. One patient whose initial ablation was directed at both scar- and Purkinje-related VT developed another focal Purkinje VT. On the contrary, Kumar et al.10 reported the highest rate of relapse (71%) after first ablation, with a significant proportion of patients requiring a second (43%) or third ablation (10%).

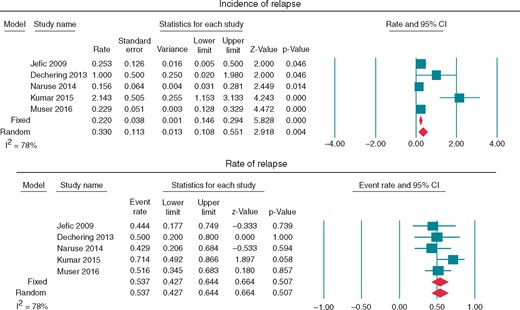

Overall, the pooling of our data (Figure 2) shows that catheter ablation can be an effective method to diminish or abolish VTs in patients with CS, with an incidence of relapse 0.33 (95% CI 0.108–0.551, P < 0.004). When a less stringent endpoint was used (i.e. freedom from arrhythmia or reduction of ventricular arrhythmia burden), 61 (88.4%) patients improved following catheter ablation.

Forest plots assessing (A) incidence of relapse and (B) rate of relapse.

Procedural complications

It is worth mentioning that of the five studies, two studies15,16 did not provide any information related to procedural complications. One study14,15 claimed no complications during ablation and two studies10,18 reported on any form of complication (Table 3). More specifically, Kumar et al.10 reported that a patient developed electromechanical dissociation and ultimately required a biventricular assistance device and later underwent heart transplant (Table 3). In addition, Muser et al.17 reported that one patient had perforation of the coronary sinus, while another one developed a total occlusion of a small coronary artery branch. The rate of procedural complications for each study did not exceed 4.7–6.4%, respectively. Overall, no procedural deaths were reported.

| Study . | Procedural complications % (N) . | Procedural mortality % (N) . | FUP duration (months) . | Transplant % (N) . | Mortality during FUP % (N) . | Relapse rate % (N) . | VT burden decrease in 6 months % (N) . | Redo procedures % (N) . | Predictors of procedural success (freedom from VT relapse) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jefic 200914 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 20 | 0% (0) | 11.1% (1) | 44% (4) | 100% (9) | 33% (3) 2nd | N/A |

| Deschering 201315 | N/A | 0% (0) | 6 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 50% (4) | 100% (8) | 12.5% (1) 2nd | N/A |

| Naruse 201416 | N/A | 0% (0) | 33 | N/A | N/A | 43% (6) | N/A | 28.6% (4) 2nd | N/A |

| Kumar 201510 | Electromechanical dissociation, requiring biventricular assistant device and transplant 4.7% (1) | 0% (0) | 24 (median) | 23.8% (5) | 19% (4) | 71% (15) | 76% (16) |

| N/A |

| Muser 201617 |

| 0% (0) | 30 (median) | 12.9% (4) | 3.2% (1) | 52% (16) | 90% (28) |

|

|

| Total/Mean | 2.7%b | 0% | — | 13%/(9) | 8.7%/(6) | 54.2%/(45) | 88.4%/(61) |

| — |

| Study . | Procedural complications % (N) . | Procedural mortality % (N) . | FUP duration (months) . | Transplant % (N) . | Mortality during FUP % (N) . | Relapse rate % (N) . | VT burden decrease in 6 months % (N) . | Redo procedures % (N) . | Predictors of procedural success (freedom from VT relapse) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jefic 200914 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 20 | 0% (0) | 11.1% (1) | 44% (4) | 100% (9) | 33% (3) 2nd | N/A |

| Deschering 201315 | N/A | 0% (0) | 6 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 50% (4) | 100% (8) | 12.5% (1) 2nd | N/A |

| Naruse 201416 | N/A | 0% (0) | 33 | N/A | N/A | 43% (6) | N/A | 28.6% (4) 2nd | N/A |

| Kumar 201510 | Electromechanical dissociation, requiring biventricular assistant device and transplant 4.7% (1) | 0% (0) | 24 (median) | 23.8% (5) | 19% (4) | 71% (15) | 76% (16) |

| N/A |

| Muser 201617 |

| 0% (0) | 30 (median) | 12.9% (4) | 3.2% (1) | 52% (16) | 90% (28) |

|

|

| Total/Mean | 2.7%b | 0% | — | 13%/(9) | 8.7%/(6) | 54.2%/(45) | 88.4%/(61) |

| — |

N/A, non-available; N, number; FUP, follow-up; VT, ventricular tachycardia; LGE, lade gadolinium enhancement; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; RV, right ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Only on Univariate Cox Regression: LVEF (per 10%) HR = 1.69, 95% CI: 1.14–2.51, P = 0.01; Moderate to severe RV dysfunction HR = 1.83, 95% CI 1.08–3.10; P = 0.03; NYHA class III/IV HR 2.43, 95% CI 1.26–4.68, P = 0.01; Positive baseline PET HR = 3.86, 95% CI 1.01–14.74, P = 0.05; > 5 segments involved by LGE in MRI HR = 5.02, 95% CI 1.25–20.16, P = 0.02.

bAmong studies with available data.

| Study . | Procedural complications % (N) . | Procedural mortality % (N) . | FUP duration (months) . | Transplant % (N) . | Mortality during FUP % (N) . | Relapse rate % (N) . | VT burden decrease in 6 months % (N) . | Redo procedures % (N) . | Predictors of procedural success (freedom from VT relapse) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jefic 200914 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 20 | 0% (0) | 11.1% (1) | 44% (4) | 100% (9) | 33% (3) 2nd | N/A |

| Deschering 201315 | N/A | 0% (0) | 6 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 50% (4) | 100% (8) | 12.5% (1) 2nd | N/A |

| Naruse 201416 | N/A | 0% (0) | 33 | N/A | N/A | 43% (6) | N/A | 28.6% (4) 2nd | N/A |

| Kumar 201510 | Electromechanical dissociation, requiring biventricular assistant device and transplant 4.7% (1) | 0% (0) | 24 (median) | 23.8% (5) | 19% (4) | 71% (15) | 76% (16) |

| N/A |

| Muser 201617 |

| 0% (0) | 30 (median) | 12.9% (4) | 3.2% (1) | 52% (16) | 90% (28) |

|

|

| Total/Mean | 2.7%b | 0% | — | 13%/(9) | 8.7%/(6) | 54.2%/(45) | 88.4%/(61) |

| — |

| Study . | Procedural complications % (N) . | Procedural mortality % (N) . | FUP duration (months) . | Transplant % (N) . | Mortality during FUP % (N) . | Relapse rate % (N) . | VT burden decrease in 6 months % (N) . | Redo procedures % (N) . | Predictors of procedural success (freedom from VT relapse) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jefic 200914 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 20 | 0% (0) | 11.1% (1) | 44% (4) | 100% (9) | 33% (3) 2nd | N/A |

| Deschering 201315 | N/A | 0% (0) | 6 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 50% (4) | 100% (8) | 12.5% (1) 2nd | N/A |

| Naruse 201416 | N/A | 0% (0) | 33 | N/A | N/A | 43% (6) | N/A | 28.6% (4) 2nd | N/A |

| Kumar 201510 | Electromechanical dissociation, requiring biventricular assistant device and transplant 4.7% (1) | 0% (0) | 24 (median) | 23.8% (5) | 19% (4) | 71% (15) | 76% (16) |

| N/A |

| Muser 201617 |

| 0% (0) | 30 (median) | 12.9% (4) | 3.2% (1) | 52% (16) | 90% (28) |

|

|

| Total/Mean | 2.7%b | 0% | — | 13%/(9) | 8.7%/(6) | 54.2%/(45) | 88.4%/(61) |

| — |

N/A, non-available; N, number; FUP, follow-up; VT, ventricular tachycardia; LGE, lade gadolinium enhancement; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; RV, right ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Only on Univariate Cox Regression: LVEF (per 10%) HR = 1.69, 95% CI: 1.14–2.51, P = 0.01; Moderate to severe RV dysfunction HR = 1.83, 95% CI 1.08–3.10; P = 0.03; NYHA class III/IV HR 2.43, 95% CI 1.26–4.68, P = 0.01; Positive baseline PET HR = 3.86, 95% CI 1.01–14.74, P = 0.05; > 5 segments involved by LGE in MRI HR = 5.02, 95% CI 1.25–20.16, P = 0.02.

bAmong studies with available data.

Discussion

In the present systematic review, we have shown that catheter ablation can decrease the overall ventricular arrhythmia burden in 88.4% of CS patients with recurrent VT, and render patients free from VT relapse in 45.8%. This was observed in cases where AAD and immunosuppression treatment could not prevent VT relapse. However, we have found that 26 patients underwent a second procedure, while a third procedure was required in 4 patients.

Although the results of VT ablation appear to be promising, the available data are limited, based on small cohort studies without controls and inherent poor quality. Despite those limitations, VT ablation in CS has quite comparable efficacy to VT ablation in other structural heart disease patients such ischaemic cardiomyopathy (ICM) and non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy (NIDCM). The Multicenter Thermocool VT Ablation Trial21 was a prospective observational trial that enrolled 231 patients with recurrent monomorphic VT in setting of ICM treated with catheter ablation. After a follow-up of 6 months, it was found that 53% of patients were free from recurrent incessant VT or intermittent VT. In the Ventricular Tachycardia Ablation in Coronary Heart Disease (VTACH)22 study of the 107 patients included in the analysis, median time to VT/VF recurrence in the ablation group was longer than the control group (18.6 vs. 5.9 months), while after 2 years, those randomized to ablation had superior VT/VF-free survival (47 vs. 29%; P = 0.045). The data regarding to NIDCM are limited and without large prospective randomized trials describing the outcomes following VT ablation. One large single-centre retrospective observational study,9 examined 119 patients with NIDCM and reported that 79 patients were free of VT after 12 months. Importantly, the Heart Center of Leipzig VT (HELP-VT) study23 which enrolled 63 patients with NIDCM and 164 patients with ICM demonstrated that the acute procedural success was achieved in 66.7% of those with NIDCM (vs. 77.4% in ICM; P = 0.125). Long-term VT-free survival was significantly lower for NIDCM compared with ICM: VT-free survival rates at 1 year were 40.5% for NIDCM and 57% for ICM. Cumulative VT-free survival after median follow-up periods of 20 and 27 months for NIDCM and ICM, respectively, were 23 and 43% (P = 0.01).

With regards to safety, the risk of complications may be as high as 6.4%, suggesting that the overall net benefit of the procedure may be acceptable, but appropriate patient selection and consenting is of utmost importance. Importantly, this risk rate appears to be comparable, or possibly lower, to the overall risk of complications (8–10%) from catheter ablation as this was assessed in a previous meta-analysis.24

Therapeutic approaches targeting ventricular tachycardia in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis

Typically, immunosuppression and antiarrhythmics are the first line treatments to manage VT in CS patients.20,25 Corticosteroids along with steroid-sparing agents such as methotrexate, and cyclophosphamide are very often used.20,25,26 Studies have shown that corticosteroid therapy can be effective for managing ventricular arrhythmias at the early stage, but less effective at the late stage.27 However, the evidence for the role of immunosuppressive therapy is rather conflicting.28,29 Muser et al.18 suggested that patients with more inflammation at baseline are at higher risk of relapse. Therefore, a positron emission tomography (PET) scan at baseline may be of importance to identify those individuals who are more likely to benefit from aggressive medical therapy. Although the optimal timing for ablation remains unclear, Muser et al.18 recommend that a procedure should be performed after the active disease phase so as to achieve the best possible results. This is presumably due to the development of fibrosis in the substrate making it more amenable to ablation plus the lack of inflammatory infiltrate promoting automatic activity and forming new pro-arrhythmic sites.

Antiarrhythmic drugs such as amiodarone, mexiletine, β-blockers, lidocaine, and others alone or in combination with immunosuppression therapy play a significant role in the management of VT in these patients.20 Despite the beneficial effects of corticosteroids, there are still data supporting that these could potentially result to worsening of VT when initiated shortly after the active phase28,29 or exert no effects at all.30 It has been suggested that treatment with steroids is effective mainly in early stages of the disease and before the development of overt clinical cardiac symptoms.31 Heart transplantation is also an option in CS non-responsive to medical management, however it has been associated with increased mortality.20,26

Ablation of ventricular tachycardia in cardiac sarcoidosis

One of the issues of CS patients who are ICD recipients is the frequent occurrence of shocks and/or present with arrhythmia storms, in spite of medical therapy.32–35 The lack of effective non-invasive approaches to decrease the overall ventricular arrhythmia burden in this population has led to further investigation, pointing to catheter ablation as a possible approach for managing VT refractory to immunosuppressive and antiarrhythmic therapy.

The pooling of our data suggests that catheter ablation of VT is an acceptable therapeutic option being effective in eradicating or decreasing the overall arrhythmia burden. However, the lack of a control group in all studies does not allow us to rule out the possibility of a placebo effect of ablation itself.

Ventricular tachycardia in patients with CS is challenging. According to our data, several VT morphologies are usually identified. Endocardial mapping of both ventricles is frequently required, with epicardial mapping and ablation needed in up to a third of procedures. More than a third of patients will require redo procedures, and complete VT eradication will occur only in half of patients. However, if we accept the broader endpoint of reduction of ventricular arrhythmia burden, 88.4% or even more than 90% of patients will experience some form of benefit. The possible occurrence of major complications in almost 5% of patients doesn’t make this a prohibitive procedure, but reinforces the need of careful patient selection. However, as shown before, recurrent VT in CS patients may be a surrogate of adverse prognosis, with death and transplant occurring in six and nine patients respectively, in spite of ablation.

Detailed endocardial and epicardial voltage mapping of CS patients shows confluent RV scarring with patchy LV involvement, with a predilection for the septum, anterior wall, and the outflow tracts.10 High-density mapping is important to better define scar areas, isthmuses and its wider adoption may result in better long-term procedural outcomes. A limitation of current mapping systems is to define to structural and functional substrates most likely to support VT and the inability to map intramural circuits. Potential approaches include the application of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to identify potential channels in scar that can then be mapped and ablated as has been described in Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) & ischaemic heart disease (IHD).36 This is critically dependent on image resolution with gadolinium late enhancement which will be reduced if the patient has an ICD as this reduces the resolution achievable by MRI since wide band image acquisition is required giving 4–8 mm as opposed to 1 mm sectioning of the substrate. This fact suggests the potential need of routine cardiac MRI scan in this population before implanting an ICD.

Obtaining epicardial access may be a challenging process in less experienced centres, and is associated with peri-procedural complications. Possible indications for mapping the epicardium are persistent inducibility after endocardial ablation, recurrent VT following index ablation, 12-lead ECG suggesting epicardial origin, evidence of epicardial substrate on pre-procedural MRI, presence of unipolar electrogram abnormalities in the presence of normal bipolar electrogram voltage.18

Elimination of all inducible VTs is a difficult goal because of the diffuse and heterogeneous RV involvement, intramural scarring, or close proximity to critical epicardial structures, such as the coronary arteries, which prohibits ablation.10 The lack of ability to achieve transmural lesions for circuits deep in the septum or hypertrophied sites is a current limitation of ablation technology.

Real-time contact force monitoring and aiming at higher force-time-integral values or ablation index may lead to more transmural lesion formation. Use of bipolar radiofrequency ablation,37,38 transcoronary alcohol ablation,39 and needle catheter ablation40 may be different alternatives for achieving transmural lesions, and neutralizing deep intramyocardial foci. Unfortunately, the benefit of these strategies has not yet been systematically assessed for CS patients.40

In the studies included in our systematic review, loss of pacing capture in the ablated tissue or drops in impedance during ablation were the strategies used to document successful RF delivery and lesion creation.

Due to the intermittent nature of CS (active vs. inactive state), one of the main issues for cardiac electrophysiologists is the difference in VT inducibility between the inactive and active stages. One could argue that the main difficulty is actually not so much the intermittent nature, but the progressive and dynamic nature of the course of CS in some of these patients. The substrate is often changing and new arrhythmias may develop as well as recurrences may occur. Moreover, inability to map these tachycardias due to their instability electrically/haemodynamically may indeed have an impact on long-term procedural success, but it may also reinforce the importance of medical therapy in the active phase to reduce inflammation and applying thorough substrate-based ablation with targeting and eradication of all late potential areas.

To summarize, our findings suggest that even though VT ablation can be employed to CS patients with refractory VT, strong and high-quality data supporting its use and efficacy are absent. Data directly comparing VT ablation with pharmacologic therapy are missing. However, it is worth mentioning that in all studies, patients who did not respond to medical therapy, underwent catheter ablation. This indicates that ablation was reserved for the most severe and recurrent/refractory forms of VT. Randomization to catheter ablation vs. medical therapy in such circumstances is not devoid of ethical issues, as it is unlikely physician would deny a patient the possibility of such a life-saving treatment option following unsuccessful non-invasive medical management. However, primary prevention ablation in cases of inducible VT following stabilisation with medical therapy especially in ICD candidates could be considered in a multi-centre study.

Limitations

Several limitations in the analysis performed in the present systematic review need to be acknowledged. Firstly, we were not able to analyse data from case-control design due to the absence of control groups in all studies. Some studies included patients with CS not undergoing catheter ablation, as they were stable on medical therapy, and therefore these could not be classified as controls, as they appeared to have a less aggressive disease compared to those undergoing ablation (recurrent VT despite medical therapy). Secondly, including single or dual-centre case series, and the large discrepancy in the demographic characteristics and medical management may explain part of the observed heterogeneity. Thirdly, missing data on concomitant medication, major events like death and/or transplantation during follow-up, outcomes of different ablation strategies (activation mapping vs. substrate ablation), and procedural complications impact on the quality of the analyses. Fourthly, all included studies were conducted in centres with high levels of experience in VT ablation, and therefore the results of can only be extrapolated to centres with similar expertise. The results of VT ablation in sarcoid patients in low experience centres remain to be assessed, and in face of the complexity of the substrate, referral to highly experienced tertiary centres would be advisable. Systematic assessment of ablation through multi-centre studies is required to evaluate the broad use of ablation as therapeutic approach in CS patients with refractory VT. Overall, the present data refer to patients with recurrent/refractory VT, and therefore cannot be extrapolated to all patients with sarcoidosis presenting with VT, namely the first episode of appropriate shock.

Conclusions

Data arising from small non-controlled cohort studies suggest that catheter ablation may be an important treatment option for refractory VT in CS patients. In fact, catheter ablation can result to acceptable rates of freedom from arrhythmia relapse in nearly 55% of patients in almost all studies, as well as to a reduction of arrhythmia burden in 88% (or more) of patients. Moreover, freedom from arrhythmia in almost half of patients occurs at the expense of a non-negligible (up to 5%) rate of major complications. However, studies on this topic are observational non-controlled case series, with low methodological quality. Therefore, future well-designed randomized controlled trials or large-scale registries assessing this specific patient population are required.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Europace online.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding

P.D.L. is supported by UCL/UCLH Biomedicine NIHR. He has received educational grants from Boston Scientific & Medtronic, speaker fees from Boston Scientific.

References

Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J et al.

Zipes DP, Camm AJ, Borggrefe M, Buxton AE, Chaitman B, Fromer M et al.

Author notes

Nikolaos Papageorgiou and Rui Providência contributed equally to the study.