-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Connor A. Emdin, Tom Callender, Jun Cao, Kazem Rahimi, Effect of antihypertensive agents on risk of atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of large-scale randomized trials, EP Europace, Volume 17, Issue 5, May 2015, Pages 701–710, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euv021

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

High blood pressure is known to be associated with future risk of atrial fibrillation. Whether such risks can be reduced with antihypertensive therapy is less clear. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of large-scale randomized trials that have reported the effect of antihypertensive agents on atrial fibrillation.

MEDLINE was searched for randomized trials published between 1966 and February 2014. Randomized, controlled trials were eligible for inclusion if they tested an antihypertensive agent and reported atrial fibrillation as an outcome. Atrial fibrillation, reported as trial outcome or adverse event, and study characteristics were extracted by investigators. In 27 trials with 214 763 randomized participants and 9929 events of atrial fibrillation, pooled using inverse-variance weighted fixed effects meta-analysis, antihypertensive therapy reduced the risk of atrial fibrillation by 10% [risk ratio (RR) 0.90; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.86, 0.94]. However, the proportional effects differed significantly between trials (P < 0.001 for heterogeneity). In trials that included patients with no prior heart disease, or patients with coronary artery disease but no heart failure, no significant effects were found (RR 1.02; CI 0.88, 1.18 and RR 0.95; CI 0.89, 1.01, respectively). Conversely, proportional effects were larger in trials that predominantly included patients with heart failure (RR 0.81; CI 0.74, 0.87). When classes of medication were compared against each other, no significant differences in effects on atrial fibrillation were observed.

Antihypertensive therapy reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation modestly but benefits appear to be larger in patients with heart failure, with no clear evidence of benefit in patients without heart failure. Previous suggestions of class-specific effects could not be confirmed in this more comprehensive analysis.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation is the most common cardiac arrhythmia and poses an increasing burden on patients and health systems worldwide. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation across all ages in Europe and North America is 1–2%, and in other regions of the world 0.1–4%.1 Since 1990, total disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) per person attributable to atrial fibrillation has increased by 50%, reaching 3.5 million DALYs worldwide in 2010.2 Efforts to reduce the burden of atrial fibrillation through traditional antiarrhythmic drugs have been hampered by the significant safety issues associated with the use of such therapies.3 On the other hand, some of the safest therapies for cardiovascular risk reduction, such as statins, have not been shown to have any conclusive effect on risk of atrial fibrillation.4 Therefore, the identification of other pharmacological therapies to reduce the incidence of atrial fibrillation is of critical importance.

Hypertension has been long recognized as a risk factor for the development of atrial fibrillation.5 In an analysis of the Framingham cohort, men and women with hypertension (defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥160 mmHg or a diastolic pressure ≥95 mmHg) had 50 and 40% greater risk for the development of atrial fibrillation, respectively.5 Similarly, an analysis of 5000 individuals in the Cardiovascular Health Study indicated that a 10 mmHg higher baseline systolic pressure was associated with an 11% greater risk for the development of atrial fibrillation over a 3-year follow-up.6

Whether pharmacological blood pressure management reduces the risk of atrial of fibrillation is less certain. A meta-analysis of renin-angiotensin inhibitors (RAS) concluded that such agents reduce the risk of atrial fibrillation by 28% [95% confidence interval (CI) 15%, 40%].7 However, this could not be confirmed in a later trial of perindopril and indapamide in patients with diabetes (HR 0.92; CI 0.74, 1.13)8 and in a second trial of irbesartan in patients with atrial fibrillation (RR 0.97: CI 0.85, 1.10).9 On the other hand, a meta-analysis of beta-blockers in heart failure concluded that beta-blockade reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation by 27%.10 However, this analysis did not investigate the effect of other antihypertensive agents or the effect of beta-blockade in other patient groups. It is, therefore, unclear whether the observed effect is specific to beta-blockade or restricted to patients with heart failure.

No meta-analysis, to our best knowledge, has attempted to investigate whether antihypertensive therapy, in general, reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation and whether different classes of antihypertensives have differential effects. We therefore undertook such a meta-analysis, in an attempt to reduce existing uncertainties around the effect of antihypertensive therapy on atrial fibrillation.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines.11

Data sources and searches

The search strategy used in this meta-analysis was derived from an existing strategy used to identify trials which tested an antihypertensive agent (regardless of whether it was used for blood pressure lowering) in any patient population.12 This includes trials which tested antihypertensive agents for purposes of blood pressure lowering as well as secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and management heart failure, although these populations were examined separately in a secondary analysis (described below). Trials which compared one class of antihypertensive agent against another class were also included, but were analysed separate from trials comparing an antihypertensive agent against placebo or control. Search terms were ‘anti-hypertensive agents’ OR ‘hypertension’ OR ‘diuretics, thiazide’ OR ‘angiotensin-converting enzyme’ OR ‘receptors, angiotensin/antagonists & inhibitors’ OR ‘tetrazoles’ OR ‘calcium channel blockers’ or ‘vasodilator agents’ or the names of all blood pressure lowering drugs listed in the British National Formulary as keywords or text words or the MESH term blood pressure [drug effects]. MEDLINE was searched using this strategy from 1966 to February 2014. Studies were restricted to those of type ‘clinical trial’ or ‘controlled clinical trial’ or ‘randomized controlled trial’ or ‘meta-analysis’ with a journal restriction to core clinical journals applied. Additionally, bibliographies of identified meta-analyses, reviews, and individual trials were searched by hand to further identify eligible trials. We then manually examined whether each trial reported atrial fibrillation events and searched for any reporting of atrial fibrillation in secondary publications.

Study selection

Randomized, controlled trials published between 1966 and 2014 on MEDLINE were eligible for inclusion. We included all large (>1000 patient-years in each arm) randomized controlled trials of antihypertensive therapy, provided they had reported events of atrial fibrillation as pre-defined study outcome or from adverse event reports. As in the Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration,13 antihypertensive therapy was defined as treatment with diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), calcium channel blockers (CCBs), or beta-blockers. We did not place any restriction on the patient populations eligible for inclusion or the primary objective of the trial; trials conducted in patients with heart failure and after myocardial infarction were included. We also did not exclude trials which reported atrial fibrillation as an adverse event or routinely collected event. The use of routine unadjudicated events is unlikely to result in biased estimates (provided sufficient number of events can be gathered) because any under- or over-reporting would affect both arms of the trial equally.14,15

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two researchers (C.E. and J.C.) independently screened all abstracts and acquired full text papers for potentially eligible studies. These were then reviewed in full text independently by two researchers (C.E. and T.C.), with differences resolved by consensus. Once all eligible trials were identified, two researchers (C.E. and J.C.) extracted information independently from each study. Number of individuals in the treatment and control arms, number of atrial fibrillation events in both arms, baseline blood pressure (systolic and diastolic), inclusion criteria, and type of event (endpoint/adverse event) were recorded. If a hazard ratio was provided, we utilized that ratio as a relative risk for the meta-analysis, as hazard ratios avoid censoring associated with the use of tabular data and have greater statistical power. However, if a hazard ratio was not provided, a relative risk ratio (RR) from the total number of events was used. For one trial, the total number of individuals in each arm without atrial fibrillation at baseline was not available, but the number of atrial fibrillation events in each arm was.16 Therefore, to calculate an RR for the trial, equal sized arms were assumed, as randomization would distribute baseline atrial fibrillation approximately equally. Two trials reported summary results for atrial fibrillation/flutter, which were considered as atrial fibrillation for this analysis.16–18 One trial with three arms compared an ACE inhibitor, to an ARB to a combination of an ACE inhibitor and ARB.19 To include this trial in the main analysis, one of the ACE inhibitor/ARB arms was randomly selected for comparison to the ACE/ARB combination arm. One study was excluded, as it provided only a single atrial fibrillation event in the treatment arm and no events in the control arm.20

Cochrane's risk of bias tool was used to evaluate risk of bias for included trials.21 Risk of bias was evaluated on five dimensions: selection bias (defined as random sequence generation and allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of both participants and investigators), detection bias (blinding of evaluators), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), and reporting bias (selective outcome reporting). Each dimension was judged to be of low, unclear, or high risk of bias. The trial, as a whole, was then judged to be of low, unclear or high risk of bias, depending on whether risk of bias among individual dimensions would have led to bias in the reported atrial fibrillation outcome.

Data synthesis and analysis

For all analyses, overall effect estimates were calculated using inverse-variance, weighted, fixed effects analysis, with 95% CIs. Random effects meta-analysis was performed as a sensitivity analysis. Heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic and tested between subgroups using Cochran's Q statistic, with a P-value of <0.05 considered significant. Analyses were performed to address: (i) whether antihypertensive therapy reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation across all studies identified, (ii) whether the proportional effect of antihypertensive therapy differs by prior disease and risk of atrial fibrillation, and (iii) whether proportional effects vary by class of antihypertensive medication. For the main analysis, to determine whether antihypertensive therapy has an effect on risk of atrial fibrillation, we included all trials that compared either antihypertensive therapy with a placebo, that compared intensive blood pressure lowering with usual care, or that compared classes of antihypertensive therapy. As a sensitivity analysis, we excluded trials that recorded atrial fibrillation as an adverse event.

To explore heterogeneity in the effect of antihypertensive therapy on atrial fibrillation, we stratified trials by whether they were conducted in patients without heart disease, with heart disease or with heart failure. We further stratified trials by tertiles of event rate (calculated as the number of atrial fibrillation events per patient-year) to examine whether the effect of antihypertensive therapy differed by event rate.

For analysis by class of medication, we meta-analysed both the effect of each class of medication against placebo and the effect of each class of medication against all active comparators. For example, for ACE inhibitors, we meta-analysed all trials comparing ACE inhibitors against placebo and all trials comparing ACE inhibitors against active comparators separately. For one trial, ONTARGET, we excluded the combination arm from comparison by the class of medication, as it would have led to active therapy being compared against itself.19

All statistical analyses were completed with Stata 12 (Stata Corp, USA).

Results

Search results and study characteristics

A total of 10 181 abstracts were identified and screened (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1). One hundred and twenty-five randomized trials were initially identified, of which 94 were excluded for not fulfilling inclusion criteria. Three trials (CHARM program) reported atrial fibrillation combined for all three trials while two trials (SOLVD program) reported atrial fibrillation combined for both trials. CHARM and SOLVD were then each considered a single trial. As a result, 27 trials, with 9929 events in 214 763 patients, were identified (Table 1). Twenty trials involved blood pressure lowering (either testing an antihypertensive agent against a placebo or testing intensive lowering against usual care) while eight trials tested an antihypertensive against another antihypertensive agent. Eleven trials reported atrial fibrillation as an adverse event while 16 trials reported atrial fibrillation as an endpoint. Of the 20 blood pressure lowering trials, one trial (ACTIVE I) was conducted in patients with a history of atrial fibrillation, while 19 trials were conducted in patients who predominantly had no history of atrial fibrillation. Five trials were conducted in patients who predominantly had no history of coronary heart disease, 5 trials were conducted in patients with a history of coronary heart disease while 10 trials were conducted in patients with heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction.

Summary of characteristics of trials comparing antihypertensive therapy against placebo or against active control

| Name . | Inclusion criteria . | Intervention/control . | Total . | Mean age . | Male (%) . | Duration of follow-up . | BP at baseline . | Type of prevention . | Reported as . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTIVE I9 (subgroup) | History of atrial fibrillation (sinus rhythm at baseline) | Irbesartan/placebo | 1730 | 70 | 61 | 4.1 | 138/82 | Secondary prevention (history of AF) | Endpoint (committee validated) |

| Advance8 | Hypertension (diabetes mellitus) | Perindopril/indapamide/control | 10293 | 66 | 57% | 4.3 | 145/81 | Primary (sinus rhythm on baseline and no history of AF) | Endpoint (random sample validated) |

| ALLHAT18 | Hypertension (cardiovascular risk factor) | Amlodipine/chlorthalidone | 18630 | 67 | 53% | 4.9 | 146/84 | Unclear (Sinus rhythm on baseline) | Endpoint (Evaluated by external ECG centre) |

| Lisinopril/chlorthalidone | 18397 | 67 | 53% | 4.9 | 146/84 | ||||

| BEST29 | Heart Failure (NYHA class III or IV) | Bucindolol/placebo | 2708 | 60 | 78% | 2 | 117/71 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event |

| Cardio-Sis30 | Hypertension with an additional risk factor | Intense (<130 mmHg)/usual (<140 mmHg) | 10985 | 67 | 41% | 2 | 163/90 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint (committee validated) |

| CAPPP31 | Hypertension | Captopril/diuretic or beta-blocker | 1111 | 53 | 54% | 6.1 | 161/99 | Primary | Adverse event |

| Capricorn32 | Myocardial infarction (LVSD) | Carvedilol/placebo | 1959 | 63 | 74% | 1.3 | 122/74 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event (post hoc investigator validated) |

| CHARM33 | Heart Failure (Reduced or preserved ejection fraction) | Candesartan/placebo | 6379 | 65 | 68% | 3.1 | 131/77 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint (investigator reported) |

| DIABHYCAR34 | Hypertension (diabetes mellitus) | Ramipril/placebo | 4912 | 65 | 70% | 3.9 | 145/82 | Unclear | Adverse event |

| GISSI-335 | Myocardial infarction | Lisinopril/placebo | 17711 | 78% | 0.12 | Primary (sinus rhythm on baseline and no history of AF) | Endpoint (investigator reported) | ||

| HOPE36 | Hypertension (cardiovascular disease history with an additional cardiovascular risk factor) | Ramipril/placebo | 8335 | 66 | 73% | 4.5 | 138/79 | Unclear (Sinus rhythm on baseline) | Endpoint (ECGs analysed by cardiologists) |

| LIFE26 | Hypertension (left ventricular hypertrophy) | Losartan/atenolol | 8851 | 67 | 46% | 4.8 | 174/98 | Primary (sinus rhythm on baseline and no history of AF) | Endpoint (evaluated by external ECG centre) |

| MERIT-HF37 | Heart failure | Metoprolol/placebo | 3132 | 63 | 76% | 1 | 130/78 | Unclear (sinus rhythm on baseline) | Adverse event |

| NAVIGATOR38 | Hypertension (impaired glucose tolerance) | Valsartan/placebo | 8943 | 63 | 49% | 6.5 | 140/82 | Primary (sinus rhythm on baseline and no history of AF) | Adverse event (post hoc ECG or investigator reported adverse event) |

| NORDIL39 | Hypertension | Diltiazem/diuretic or beta-blocker | 10881 | 60 | 49% | 4.5 | 173/106 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint |

| ONTARGET19 | Hypertension (vascular disease or diabetes) | Telmisartan/ramipril | 16555 | 66 | 73% | 4.7 | 142/82 | Unclear (sinus rhythm on baseline) | Endpoint |

| Telmisartan + rampiril/ramipril | 16514 | 66 | 73% | 4.7 | 142/82 | ||||

| OPTIMAAL16 | Myocardial infarction with signs of heart failure or LVSD | Losartan/captopril | 4822 | 67 | 71% | 2.7 | 122/71 | Unclear (sinus rhythm on baseline) | Adverse event |

| PRAISE-240 | Heart failure (non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy) | Amlodipine/placebo | 2289 | 59 | 66% | 2.8 | 120/81 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event |

| PRoFESS41 | Hypertension (history of cerebrovascular events) | Telmisartan/placebo | 20332 | 66 | 64% | 2.5 | 144/84 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event |

| SENIORS42 | Heart Failure with reduced or preserved ejection fraction | Nebivolol/placebo | 2128 | 76 | 63% | 1.8 | 139/81 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event |

| SHEP43 | Hypertension (elderly with systolic hypertension) | Active treatment (diuretic or beta-blocker)/placebo | 4736 | 72 | 43% | 4.5 | 171/77 | Primary (atrial fibrillation was exclusion criteria) | Endpoint (evaluated by external ECG centre) |

| SOLVD (Montreal site)44 | Heart failure (mild to moderate with LVSD) | Enalapril/placebo | 374 | 57 | 90% | 2.9 | 128/79 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint (ECG interpreted by cardiologist) |

| STOP-245 | Hypertension (SBP > 180 or DBP > 105) | Enalapril or lisonpril (ACE-I)/convetional (diuretics or beta-blockers) | 4418 | 76 | 33% | 5 | 194/98 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint |

| Amiloride/convetional (diuretics or beta-blockers) | 4409 | 76 | 33% | 5 | 194/98 | ||||

| TRACE46 | Myocardial infarction (LVSD) | Trandolapril/placebo | 1577 | 67 | 72% | 2.2 | Unclear | Endpoint (post hoc investigator validated) | |

| TRANSCEND47 | Hypertension (cardiovascular diseases or diabetes with end organ damage) | Telmisartan/placebo | 5701 | 67 | 57% | 4.7 | 141/82 | Primary (described as new onset atrial fibrillation) | Endpoint |

| Val-HeFT48 | Heart failure | Valsartan/placebo | 4395 | 63 | 79% | 1.9 | 121/ | Unclear (sinus rhythm at baseline) | Adverse event |

| VALUE49 | Hypertension (high cardiovascular risk) | Valsartan/amlodipine | 13760 | 67 | 58% | 4.2 | 155/88 | Unclear | Endpoint (evaluated by external ECG centre) |

| Name . | Inclusion criteria . | Intervention/control . | Total . | Mean age . | Male (%) . | Duration of follow-up . | BP at baseline . | Type of prevention . | Reported as . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTIVE I9 (subgroup) | History of atrial fibrillation (sinus rhythm at baseline) | Irbesartan/placebo | 1730 | 70 | 61 | 4.1 | 138/82 | Secondary prevention (history of AF) | Endpoint (committee validated) |

| Advance8 | Hypertension (diabetes mellitus) | Perindopril/indapamide/control | 10293 | 66 | 57% | 4.3 | 145/81 | Primary (sinus rhythm on baseline and no history of AF) | Endpoint (random sample validated) |

| ALLHAT18 | Hypertension (cardiovascular risk factor) | Amlodipine/chlorthalidone | 18630 | 67 | 53% | 4.9 | 146/84 | Unclear (Sinus rhythm on baseline) | Endpoint (Evaluated by external ECG centre) |

| Lisinopril/chlorthalidone | 18397 | 67 | 53% | 4.9 | 146/84 | ||||

| BEST29 | Heart Failure (NYHA class III or IV) | Bucindolol/placebo | 2708 | 60 | 78% | 2 | 117/71 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event |

| Cardio-Sis30 | Hypertension with an additional risk factor | Intense (<130 mmHg)/usual (<140 mmHg) | 10985 | 67 | 41% | 2 | 163/90 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint (committee validated) |

| CAPPP31 | Hypertension | Captopril/diuretic or beta-blocker | 1111 | 53 | 54% | 6.1 | 161/99 | Primary | Adverse event |

| Capricorn32 | Myocardial infarction (LVSD) | Carvedilol/placebo | 1959 | 63 | 74% | 1.3 | 122/74 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event (post hoc investigator validated) |

| CHARM33 | Heart Failure (Reduced or preserved ejection fraction) | Candesartan/placebo | 6379 | 65 | 68% | 3.1 | 131/77 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint (investigator reported) |

| DIABHYCAR34 | Hypertension (diabetes mellitus) | Ramipril/placebo | 4912 | 65 | 70% | 3.9 | 145/82 | Unclear | Adverse event |

| GISSI-335 | Myocardial infarction | Lisinopril/placebo | 17711 | 78% | 0.12 | Primary (sinus rhythm on baseline and no history of AF) | Endpoint (investigator reported) | ||

| HOPE36 | Hypertension (cardiovascular disease history with an additional cardiovascular risk factor) | Ramipril/placebo | 8335 | 66 | 73% | 4.5 | 138/79 | Unclear (Sinus rhythm on baseline) | Endpoint (ECGs analysed by cardiologists) |

| LIFE26 | Hypertension (left ventricular hypertrophy) | Losartan/atenolol | 8851 | 67 | 46% | 4.8 | 174/98 | Primary (sinus rhythm on baseline and no history of AF) | Endpoint (evaluated by external ECG centre) |

| MERIT-HF37 | Heart failure | Metoprolol/placebo | 3132 | 63 | 76% | 1 | 130/78 | Unclear (sinus rhythm on baseline) | Adverse event |

| NAVIGATOR38 | Hypertension (impaired glucose tolerance) | Valsartan/placebo | 8943 | 63 | 49% | 6.5 | 140/82 | Primary (sinus rhythm on baseline and no history of AF) | Adverse event (post hoc ECG or investigator reported adverse event) |

| NORDIL39 | Hypertension | Diltiazem/diuretic or beta-blocker | 10881 | 60 | 49% | 4.5 | 173/106 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint |

| ONTARGET19 | Hypertension (vascular disease or diabetes) | Telmisartan/ramipril | 16555 | 66 | 73% | 4.7 | 142/82 | Unclear (sinus rhythm on baseline) | Endpoint |

| Telmisartan + rampiril/ramipril | 16514 | 66 | 73% | 4.7 | 142/82 | ||||

| OPTIMAAL16 | Myocardial infarction with signs of heart failure or LVSD | Losartan/captopril | 4822 | 67 | 71% | 2.7 | 122/71 | Unclear (sinus rhythm on baseline) | Adverse event |

| PRAISE-240 | Heart failure (non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy) | Amlodipine/placebo | 2289 | 59 | 66% | 2.8 | 120/81 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event |

| PRoFESS41 | Hypertension (history of cerebrovascular events) | Telmisartan/placebo | 20332 | 66 | 64% | 2.5 | 144/84 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event |

| SENIORS42 | Heart Failure with reduced or preserved ejection fraction | Nebivolol/placebo | 2128 | 76 | 63% | 1.8 | 139/81 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event |

| SHEP43 | Hypertension (elderly with systolic hypertension) | Active treatment (diuretic or beta-blocker)/placebo | 4736 | 72 | 43% | 4.5 | 171/77 | Primary (atrial fibrillation was exclusion criteria) | Endpoint (evaluated by external ECG centre) |

| SOLVD (Montreal site)44 | Heart failure (mild to moderate with LVSD) | Enalapril/placebo | 374 | 57 | 90% | 2.9 | 128/79 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint (ECG interpreted by cardiologist) |

| STOP-245 | Hypertension (SBP > 180 or DBP > 105) | Enalapril or lisonpril (ACE-I)/convetional (diuretics or beta-blockers) | 4418 | 76 | 33% | 5 | 194/98 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint |

| Amiloride/convetional (diuretics or beta-blockers) | 4409 | 76 | 33% | 5 | 194/98 | ||||

| TRACE46 | Myocardial infarction (LVSD) | Trandolapril/placebo | 1577 | 67 | 72% | 2.2 | Unclear | Endpoint (post hoc investigator validated) | |

| TRANSCEND47 | Hypertension (cardiovascular diseases or diabetes with end organ damage) | Telmisartan/placebo | 5701 | 67 | 57% | 4.7 | 141/82 | Primary (described as new onset atrial fibrillation) | Endpoint |

| Val-HeFT48 | Heart failure | Valsartan/placebo | 4395 | 63 | 79% | 1.9 | 121/ | Unclear (sinus rhythm at baseline) | Adverse event |

| VALUE49 | Hypertension (high cardiovascular risk) | Valsartan/amlodipine | 13760 | 67 | 58% | 4.2 | 155/88 | Unclear | Endpoint (evaluated by external ECG centre) |

Summary of characteristics of trials comparing antihypertensive therapy against placebo or against active control

| Name . | Inclusion criteria . | Intervention/control . | Total . | Mean age . | Male (%) . | Duration of follow-up . | BP at baseline . | Type of prevention . | Reported as . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTIVE I9 (subgroup) | History of atrial fibrillation (sinus rhythm at baseline) | Irbesartan/placebo | 1730 | 70 | 61 | 4.1 | 138/82 | Secondary prevention (history of AF) | Endpoint (committee validated) |

| Advance8 | Hypertension (diabetes mellitus) | Perindopril/indapamide/control | 10293 | 66 | 57% | 4.3 | 145/81 | Primary (sinus rhythm on baseline and no history of AF) | Endpoint (random sample validated) |

| ALLHAT18 | Hypertension (cardiovascular risk factor) | Amlodipine/chlorthalidone | 18630 | 67 | 53% | 4.9 | 146/84 | Unclear (Sinus rhythm on baseline) | Endpoint (Evaluated by external ECG centre) |

| Lisinopril/chlorthalidone | 18397 | 67 | 53% | 4.9 | 146/84 | ||||

| BEST29 | Heart Failure (NYHA class III or IV) | Bucindolol/placebo | 2708 | 60 | 78% | 2 | 117/71 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event |

| Cardio-Sis30 | Hypertension with an additional risk factor | Intense (<130 mmHg)/usual (<140 mmHg) | 10985 | 67 | 41% | 2 | 163/90 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint (committee validated) |

| CAPPP31 | Hypertension | Captopril/diuretic or beta-blocker | 1111 | 53 | 54% | 6.1 | 161/99 | Primary | Adverse event |

| Capricorn32 | Myocardial infarction (LVSD) | Carvedilol/placebo | 1959 | 63 | 74% | 1.3 | 122/74 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event (post hoc investigator validated) |

| CHARM33 | Heart Failure (Reduced or preserved ejection fraction) | Candesartan/placebo | 6379 | 65 | 68% | 3.1 | 131/77 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint (investigator reported) |

| DIABHYCAR34 | Hypertension (diabetes mellitus) | Ramipril/placebo | 4912 | 65 | 70% | 3.9 | 145/82 | Unclear | Adverse event |

| GISSI-335 | Myocardial infarction | Lisinopril/placebo | 17711 | 78% | 0.12 | Primary (sinus rhythm on baseline and no history of AF) | Endpoint (investigator reported) | ||

| HOPE36 | Hypertension (cardiovascular disease history with an additional cardiovascular risk factor) | Ramipril/placebo | 8335 | 66 | 73% | 4.5 | 138/79 | Unclear (Sinus rhythm on baseline) | Endpoint (ECGs analysed by cardiologists) |

| LIFE26 | Hypertension (left ventricular hypertrophy) | Losartan/atenolol | 8851 | 67 | 46% | 4.8 | 174/98 | Primary (sinus rhythm on baseline and no history of AF) | Endpoint (evaluated by external ECG centre) |

| MERIT-HF37 | Heart failure | Metoprolol/placebo | 3132 | 63 | 76% | 1 | 130/78 | Unclear (sinus rhythm on baseline) | Adverse event |

| NAVIGATOR38 | Hypertension (impaired glucose tolerance) | Valsartan/placebo | 8943 | 63 | 49% | 6.5 | 140/82 | Primary (sinus rhythm on baseline and no history of AF) | Adverse event (post hoc ECG or investigator reported adverse event) |

| NORDIL39 | Hypertension | Diltiazem/diuretic or beta-blocker | 10881 | 60 | 49% | 4.5 | 173/106 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint |

| ONTARGET19 | Hypertension (vascular disease or diabetes) | Telmisartan/ramipril | 16555 | 66 | 73% | 4.7 | 142/82 | Unclear (sinus rhythm on baseline) | Endpoint |

| Telmisartan + rampiril/ramipril | 16514 | 66 | 73% | 4.7 | 142/82 | ||||

| OPTIMAAL16 | Myocardial infarction with signs of heart failure or LVSD | Losartan/captopril | 4822 | 67 | 71% | 2.7 | 122/71 | Unclear (sinus rhythm on baseline) | Adverse event |

| PRAISE-240 | Heart failure (non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy) | Amlodipine/placebo | 2289 | 59 | 66% | 2.8 | 120/81 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event |

| PRoFESS41 | Hypertension (history of cerebrovascular events) | Telmisartan/placebo | 20332 | 66 | 64% | 2.5 | 144/84 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event |

| SENIORS42 | Heart Failure with reduced or preserved ejection fraction | Nebivolol/placebo | 2128 | 76 | 63% | 1.8 | 139/81 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event |

| SHEP43 | Hypertension (elderly with systolic hypertension) | Active treatment (diuretic or beta-blocker)/placebo | 4736 | 72 | 43% | 4.5 | 171/77 | Primary (atrial fibrillation was exclusion criteria) | Endpoint (evaluated by external ECG centre) |

| SOLVD (Montreal site)44 | Heart failure (mild to moderate with LVSD) | Enalapril/placebo | 374 | 57 | 90% | 2.9 | 128/79 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint (ECG interpreted by cardiologist) |

| STOP-245 | Hypertension (SBP > 180 or DBP > 105) | Enalapril or lisonpril (ACE-I)/convetional (diuretics or beta-blockers) | 4418 | 76 | 33% | 5 | 194/98 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint |

| Amiloride/convetional (diuretics or beta-blockers) | 4409 | 76 | 33% | 5 | 194/98 | ||||

| TRACE46 | Myocardial infarction (LVSD) | Trandolapril/placebo | 1577 | 67 | 72% | 2.2 | Unclear | Endpoint (post hoc investigator validated) | |

| TRANSCEND47 | Hypertension (cardiovascular diseases or diabetes with end organ damage) | Telmisartan/placebo | 5701 | 67 | 57% | 4.7 | 141/82 | Primary (described as new onset atrial fibrillation) | Endpoint |

| Val-HeFT48 | Heart failure | Valsartan/placebo | 4395 | 63 | 79% | 1.9 | 121/ | Unclear (sinus rhythm at baseline) | Adverse event |

| VALUE49 | Hypertension (high cardiovascular risk) | Valsartan/amlodipine | 13760 | 67 | 58% | 4.2 | 155/88 | Unclear | Endpoint (evaluated by external ECG centre) |

| Name . | Inclusion criteria . | Intervention/control . | Total . | Mean age . | Male (%) . | Duration of follow-up . | BP at baseline . | Type of prevention . | Reported as . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTIVE I9 (subgroup) | History of atrial fibrillation (sinus rhythm at baseline) | Irbesartan/placebo | 1730 | 70 | 61 | 4.1 | 138/82 | Secondary prevention (history of AF) | Endpoint (committee validated) |

| Advance8 | Hypertension (diabetes mellitus) | Perindopril/indapamide/control | 10293 | 66 | 57% | 4.3 | 145/81 | Primary (sinus rhythm on baseline and no history of AF) | Endpoint (random sample validated) |

| ALLHAT18 | Hypertension (cardiovascular risk factor) | Amlodipine/chlorthalidone | 18630 | 67 | 53% | 4.9 | 146/84 | Unclear (Sinus rhythm on baseline) | Endpoint (Evaluated by external ECG centre) |

| Lisinopril/chlorthalidone | 18397 | 67 | 53% | 4.9 | 146/84 | ||||

| BEST29 | Heart Failure (NYHA class III or IV) | Bucindolol/placebo | 2708 | 60 | 78% | 2 | 117/71 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event |

| Cardio-Sis30 | Hypertension with an additional risk factor | Intense (<130 mmHg)/usual (<140 mmHg) | 10985 | 67 | 41% | 2 | 163/90 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint (committee validated) |

| CAPPP31 | Hypertension | Captopril/diuretic or beta-blocker | 1111 | 53 | 54% | 6.1 | 161/99 | Primary | Adverse event |

| Capricorn32 | Myocardial infarction (LVSD) | Carvedilol/placebo | 1959 | 63 | 74% | 1.3 | 122/74 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event (post hoc investigator validated) |

| CHARM33 | Heart Failure (Reduced or preserved ejection fraction) | Candesartan/placebo | 6379 | 65 | 68% | 3.1 | 131/77 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint (investigator reported) |

| DIABHYCAR34 | Hypertension (diabetes mellitus) | Ramipril/placebo | 4912 | 65 | 70% | 3.9 | 145/82 | Unclear | Adverse event |

| GISSI-335 | Myocardial infarction | Lisinopril/placebo | 17711 | 78% | 0.12 | Primary (sinus rhythm on baseline and no history of AF) | Endpoint (investigator reported) | ||

| HOPE36 | Hypertension (cardiovascular disease history with an additional cardiovascular risk factor) | Ramipril/placebo | 8335 | 66 | 73% | 4.5 | 138/79 | Unclear (Sinus rhythm on baseline) | Endpoint (ECGs analysed by cardiologists) |

| LIFE26 | Hypertension (left ventricular hypertrophy) | Losartan/atenolol | 8851 | 67 | 46% | 4.8 | 174/98 | Primary (sinus rhythm on baseline and no history of AF) | Endpoint (evaluated by external ECG centre) |

| MERIT-HF37 | Heart failure | Metoprolol/placebo | 3132 | 63 | 76% | 1 | 130/78 | Unclear (sinus rhythm on baseline) | Adverse event |

| NAVIGATOR38 | Hypertension (impaired glucose tolerance) | Valsartan/placebo | 8943 | 63 | 49% | 6.5 | 140/82 | Primary (sinus rhythm on baseline and no history of AF) | Adverse event (post hoc ECG or investigator reported adverse event) |

| NORDIL39 | Hypertension | Diltiazem/diuretic or beta-blocker | 10881 | 60 | 49% | 4.5 | 173/106 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint |

| ONTARGET19 | Hypertension (vascular disease or diabetes) | Telmisartan/ramipril | 16555 | 66 | 73% | 4.7 | 142/82 | Unclear (sinus rhythm on baseline) | Endpoint |

| Telmisartan + rampiril/ramipril | 16514 | 66 | 73% | 4.7 | 142/82 | ||||

| OPTIMAAL16 | Myocardial infarction with signs of heart failure or LVSD | Losartan/captopril | 4822 | 67 | 71% | 2.7 | 122/71 | Unclear (sinus rhythm on baseline) | Adverse event |

| PRAISE-240 | Heart failure (non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy) | Amlodipine/placebo | 2289 | 59 | 66% | 2.8 | 120/81 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event |

| PRoFESS41 | Hypertension (history of cerebrovascular events) | Telmisartan/placebo | 20332 | 66 | 64% | 2.5 | 144/84 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event |

| SENIORS42 | Heart Failure with reduced or preserved ejection fraction | Nebivolol/placebo | 2128 | 76 | 63% | 1.8 | 139/81 | Mix of primary and secondary | Adverse event |

| SHEP43 | Hypertension (elderly with systolic hypertension) | Active treatment (diuretic or beta-blocker)/placebo | 4736 | 72 | 43% | 4.5 | 171/77 | Primary (atrial fibrillation was exclusion criteria) | Endpoint (evaluated by external ECG centre) |

| SOLVD (Montreal site)44 | Heart failure (mild to moderate with LVSD) | Enalapril/placebo | 374 | 57 | 90% | 2.9 | 128/79 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint (ECG interpreted by cardiologist) |

| STOP-245 | Hypertension (SBP > 180 or DBP > 105) | Enalapril or lisonpril (ACE-I)/convetional (diuretics or beta-blockers) | 4418 | 76 | 33% | 5 | 194/98 | Mix of primary and secondary | Endpoint |

| Amiloride/convetional (diuretics or beta-blockers) | 4409 | 76 | 33% | 5 | 194/98 | ||||

| TRACE46 | Myocardial infarction (LVSD) | Trandolapril/placebo | 1577 | 67 | 72% | 2.2 | Unclear | Endpoint (post hoc investigator validated) | |

| TRANSCEND47 | Hypertension (cardiovascular diseases or diabetes with end organ damage) | Telmisartan/placebo | 5701 | 67 | 57% | 4.7 | 141/82 | Primary (described as new onset atrial fibrillation) | Endpoint |

| Val-HeFT48 | Heart failure | Valsartan/placebo | 4395 | 63 | 79% | 1.9 | 121/ | Unclear (sinus rhythm at baseline) | Adverse event |

| VALUE49 | Hypertension (high cardiovascular risk) | Valsartan/amlodipine | 13760 | 67 | 58% | 4.2 | 155/88 | Unclear | Endpoint (evaluated by external ECG centre) |

Quality assessment

Of the 27 included trials, 24 were judged to be of low risk of bias (see Supplementary material online, Table S1). One trial was judged to be of unclear risk of bias, while two trials were judged to be of high risk of bias.

Effect of antihypertensive therapy on risk of atrial fibrillation

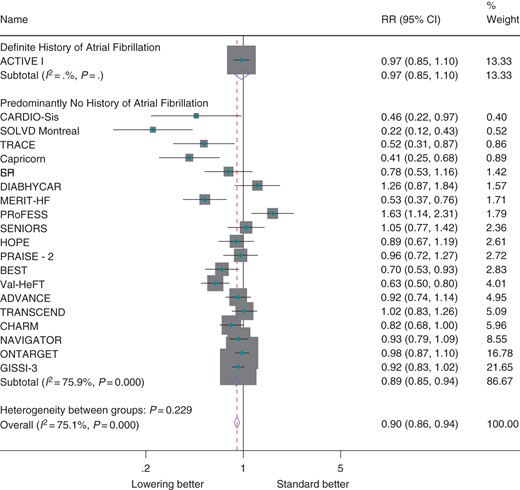

Overall, antihypertensive therapy (regardless of whether it was used for the purpose of blood pressure lowering) reduced the risk of atrial fibrillation by 10% (RR 0.90; CI 0.86, 0.94, Figure 1). In the single trial that focused on prevention of recurrences of atrial fibrillation, there was no clear effect (RR 0.97; CI 0.85, 1.10). However, there did not appear to be significant heterogeneity between this trial (secondary prevention) and trials for which history of atrial fibrillation was not an inclusion criteria (largely primary prevention, P = 0.229), although significant heterogeneity was observed among trials overall (I2 = 75.1%, P < 0.001). Exclusion of trials that reported atrial fibrillation as an adverse event had little effect on observed estimates (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2). Estimates did not differ materially when random effects meta-analysis was used (see Supplementary material online, Figure S3).

Effect of antihypertensive therapy on incidence of atrial fibrillation by history of atrial fibrillation.

Subgroup analysis

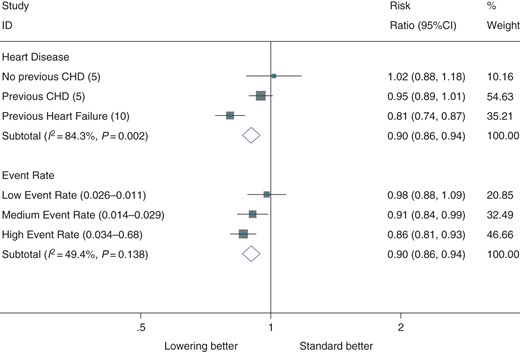

Antihypertensive therapy was significantly more effective in patients with evidence of heart failure (RR 0.81; CI 0.74, 0.87) than in patients with coronary heart disease (RR 0.95; CI 0.89, 1.01) or patients with no previous heart disease (RR 1.02; CI 0.88, 1.18, Figure 2, Pheterog = 0.002). There was a graded increase in proportional effects with increasing risk of atrial fibrillation across trials (RR 0.86, CI 0.81, 0.93 for highest event rate tertile vs. RR 0.98, CI 0.88, 1.09 for lowest event rate tertile). However, a test for heterogeneity by event rate tertile was not significant (P = 0.14). Proportional effects were slightly greater when random effects meta-analysis was used and a test for heterogeneity by event rate tertiles was significant (P = 0.04, see Supplementary material online, Figure S4).

Effect of antihypertensive therapy on incidence of atrial fibrillation, by presence of heart disease and by tertiles of event rate. The ranges of event rate, in units of atrial fibrillation events per patient year is denoted in brackets beside each tertile.

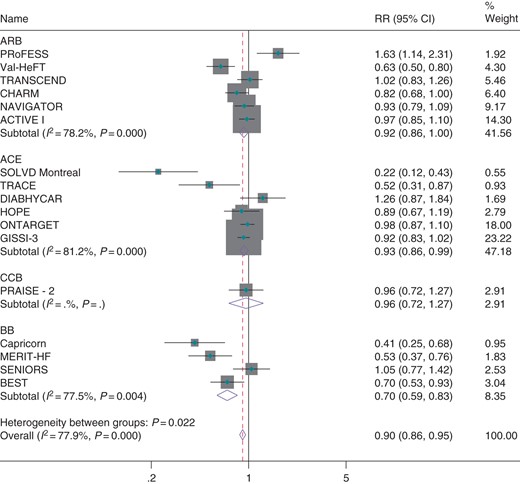

Effect of antihypertensive therapy on risk of atrial fibrillation by class of medication

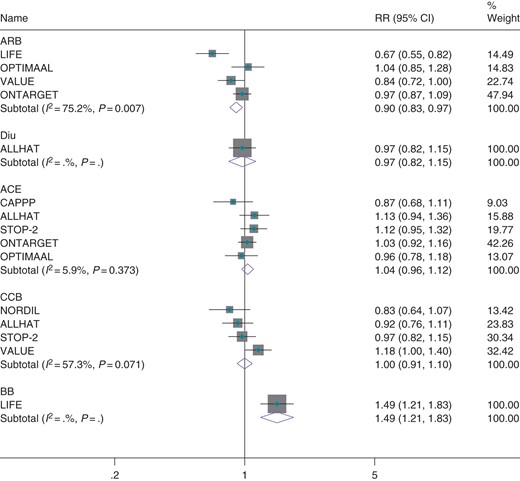

Seventeen trials compared an ACE inhibitor, ARB, CCB, or beta-blocker against a placebo. When trials were grouped by the class of medication used, significantly greater benefit was observed in trials comparing beta-blockers against placebo (RR = 0.70, CI 0.59–0.83, Figure 3) than other classes of medication against placebo (Pheterog = 0.002, Figure 3). However, all trials comparing beta-blockers against placebo were conducted in heart failure patients. When excluded, no heterogeneity was observed between the effects of ACE-I, ARBs, and CCBs on incidence of atrial fibrillation (P = 0.972). As a comparison of placebo-controlled trials may be confounded by differing patient populations between trials, we considered eight trials that compared one class of antihypertensive therapy against another class in a second analysis. When trials were grouped by the class of medication used, beta-blockers were observed to be significantly less effective than other classes of medication (Figure 4). However, this effect was solely due to the LIFE trial (the only trial comparing a beta-blocker against an active comparator). When excluded, no class of medication (ACE inhibitor, ARB, diuretic, or CCB) was observed to be more effective than any other class of medication for prevention of atrial fibrillation (see Supplementary material online, Figure S5). Estimates were similar when random effects meta-analysis was used (see Supplementary material online, Figure S6).

Effect of classes of antihypertensive medication against placebo for prevention of atrial fibrillation.

Effect of classes of antihypertensive therapies against all active comparators on atrial fibrillation.

Discussion

We identified 27 trials that reported information on 9929 events of atrial fibrillation in 214 763 randomized participants. Although pooled effects across these trials suggest that antihypertensive therapy reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation by 10% overall, proportional effects appear to be significantly greater in trials conducted in heart failure patients, where the risk of atrial fibrillation was reduced by about a quarter. Conversely, no significant effects were observed in trials conducted in patients without heart failure. When classes of medication were compared against each other, no significant differences in effects on atrial fibrillation were observed, although a single trial suggested that beta-blockers may be less effective than ARBs in individuals without heart failure.

The comprehensive approach of identifying all large blood pressure lowering trials enabled us to investigate the effect of antihypertensive therapy (regardless of whether it was used for blood pressure lowering) on atrial fibrillation by subgroups of patients and risk. The significant heterogeneity in proportional effects by disease status, with no benefit observed in patients without prior heart disease to significant benefit observed in those with known heart failure, is likely to be of clinical relevance. In response to the increasing burden of atrial fibrillation, there is growing interest in the use of antihypertensive therapy for primary prevention of atrial fibrillation.22–24 Our results suggest that such therapy may have limited benefits in patients with hypertension and no structural heart disease and would be better targeted towards patients with heart failure.

The greater relative effect observed in patients with heart failure could be either due to a heart failure-specific physiological feature or to a higher baseline risk for development of atrial fibrillation in this patient population. In support of the latter hypothesis, greater proportional effects were observed in the highest event rate tertile relative to the lowest event rate tertile. However, six of the seven trials in the highest event rate tertile were conducted in patients with a history of heart failure. It is therefore difficult to determine which hypothesis is valid or whether both hypotheses are valid. Evidence against the hypothesis that higher baseline risk is associated with higher proportional risk reductions comes from two previous trials that specifically investigated the effect of ARBs in people with previous history of atrial fibrillation.9,25 Although such patients are at very high risk of recurrent atrial fibrillation, these trials did not detect any significant effects.

In addition to allowing for investigation of population-specific effects, our inclusion of all large antihypertensive trials also allowed for the examination of evidence for antihypertensive class-specific effects on atrial fibrillation. When compared against all active comparators, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, CCBs, and diuretics were not observed to be more effective than other classes of medication. There was the suggestion that beta-blockers may be less effective than ARBs in patients with hypertension, although this estimate was derived from a single trial.26 However, our analysis largely rules out the existence of significant class-specific effects on risk of atrial fibrillation, particularly renin-angiotensin-specific effects above and beyond those provided by diuretics or CCBs.

The absence of a clear class-specific effect contrast markedly with previous observational analyses and meta-analyses of randomized trials. A propensity score-matched analysis of the Danish population from 1995 to 2010 concluded that the use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs was associated with an approximately 90% risk reduction for the onset of atrial fibrillation compared with beta-blocker therapy and a 50% risk reduction for the onset of atrial fibrillation compared with diuretics.27 These results were interpreted as evidence that renin–angiotensin inhibition significantly reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation, above and beyond the effect of blood pressure lowering. The current analysis of randomized trials indicates that the reported effects from such non-randomized comparisons are likely due to uncontrolled confounding. A meta-analysis of trials of beta-blockers in heart failure demonstrated a 27% reduction in onset of atrial fibrillation through beta-blocker therapy. The authors speculated that this observed effect may be due to beta-blockers' ability to prevent ventricular remodelling or their ability to shorten the action potential through beta adrenergic stimulation.10 Similarly, in a meta-analysis concluding that renin–angiotensin inhibitors reduce the risk of atrial fibrillation by 33%, authors suggested that this effect was greater than that predicted by blood pressure lowering alone.28 Our results demonstrate that these proposed class-specific effects are due to meta-analyses examining only a portion of the evidence, and not undertaking a comprehensive examination of all trials investigating antihypertensive therapy.

This study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the largest meta-analysis of the prevention atrial fibrillation with antihypertensive therapy. Our unique search strategy (attempting to identify all large blood pressure lowering trials and individually searching for reporting of atrial fibrillation events) allowed us to identify trials that would have been missed if key words for atrial fibrillation were used in the search strategy. Additionally, the comprehensive approach of attempting to identify all trials using antihypertensive therapies applied in this meta-analysis allows valid conclusions to be drawn on the existence of class-specific effects and analysis of effects by subgroups of patients. However, this analysis also has several limitations. First, 11 trials reported atrial fibrillation as an investigator reported adverse event, and the majority of the trials included in this analysis reported atrial fibrillation in a post hoc manner (rather than a primary or secondary adjudicated endpoint). While removal of trials reporting atrial fibrillation as an adverse event in a sensitivity analysis had no effect on the results, propensity for post hoc analyses on atrial fibrillation to be published if significant may be a source of bias. Although this would be expected to bias the results towards the extreme, we did not observe an effect for antihypertensive therapy to prevent atrial fibrillation in many of the included trials. Second, the relatively short follow-up of included trials (the majority with a median follow-up <5 years) may have precluded a longer term effect of blood pressure lowering on risk of atrial fibrillation from being observed. A third limitation of our analysis is that we did not have access to individual patient data, which would have allowed detailed time to event analyses. In meta-analyses of longer term studies when information about timing of the events is not available, shorter term treatment effects may be missed if a large proportion of people has experienced an event by the end of the study. A large individual patient data meta-analysis, such as the Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration, is better suited to investigate this possibility comprehensively.13

Conclusions

While antihypertensive therapy is associated with a significant 10% relative reduction in the risk of atrial fibrillation, this effect was confined to patients with heart failure, with no clear evidence of benefit in populations without heart failure. In contrast with previous analyses, we also found little evidence to support class-specific effects of antihypertensive therapies on risk of atrial fibrillation.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Europace online.

Authors’ contributions

C.E. and K.R. had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Everyone who contributed to this work is listed as an author.

Funding

K.R. is supported by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre and NIHR Career Development Fellowship. C.E. is supported by the Rhodes Trust. The work of the George Institute is supported by the Oxford Martin School.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References