-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

D. Zyśko, M. Szewczuk-Bogusławska, M. Kaczmarek, A.K. Agrawal, J. Rudnicki, J. Gajek, O. Melander, R. Sutton, A. Fedorowski, Reflex syncope, anxiety level, and family history of cardiovascular disease in young women: case–control study, EP Europace, Volume 17, Issue 2, February 2015, Pages 309–313, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euu200

Close - Share Icon Share

Anxiety is an emotion, which stimulates sympathetic nervous outflow potentially facilitating vasovagal reflex syncope (VVS) but reports on anxiety levels in patients with VVS are sparse.

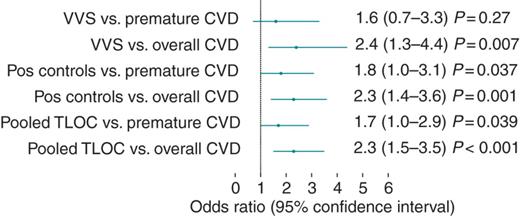

We studied anxiety levels in young women (21–40 years) referred for unexplained transient loss of consciousness (TLOC), and age-matched female controls with or without past history of TLOC (≈probable VVS). Referred patients underwent head-up tilt (HUT) according to current ESC Guidelines. State and Trait Anxiety Inventory questionnaire evaluated anxiety levels plus a questionnaire explored risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD). Sixty-five of 91 women were diagnosed with VVS on HUT. Among 549 controls, 223 (40.6%) reported at least one episode of TLOC. State-anxiety level in patients with VVS undergoing HUT (42.4 ± 9.3) was higher compared with both controls with (38.3 ± 10.2; P < 0.01) and without past TLOC history (35.9 ± 9.8; P < 0.001). Trait anxiety in patients with VVS (42.7 ± 8.4), and controls with TLOC history (42.4 ± 8.4) was higher compared with controls without TLOC history (39.7 ± 8.5; P < 0.01). In the logistic regression using controls without TLOC as reference, both VVS diagnosis and past history of TLOC were associated with family history of CVD [odds ratio (OR) 2.4, 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.3–4.4; P = 0.007, and 2.3, 1.4–3.6; P = 0.001, respectively], and this association was independent of anxiety level.

Trait anxiety and family history of CVD are increased in both young women with VVS and controls with history of TLOC. However, the height of anxiety level does not explain CVD heredity and other mechanisms may link syncope with CVD.

Higher average trait anxiety is more prevalent in young women with vasovagal syncope than in controls without transient loss of consciousness (TLOC).

Family history of premature cardiovascular diseases (CVD) is more prevalent in young women with confirmed vasovagal syncope and in controls with history of TLOC compared with controls without TLOC, independently of anxiety level.

The study indicates the existence of links between predisposition to vasovagal syncope and the family occurrence of premature CVD other than the higher anxiety level.

Introduction

Syncope is a transient, self-limited loss of consciousness caused by global cerebral hypoperfusion.1 The most common mechanism of syncope is vasovagal reflex being responsible for 60–70% of all syncope.2,3 The pathophysiology of vasovagal reflex is still elusive; however, exaggerated adrenergic activation has been suggested as a trigger in susceptible individuals.4,5 In parallel, the important role of psychological factors in triggering the vasovagal reflex indicates involvement of higher brain functions such as emotions in reflex activation.6 Anxiety is an emotion, which strongly stimulates sympathetic nervous outflow and facilitates or even triggers the vasovagal reflex,7–10 whereas relief from anxiety by simple reassurance may significantly decrease the incidence of vasovagal attacks.1,11–13

According to Spielberger et al., anxiety may be assessed as the current level of fear (state anxiety) or the continuous average level of fear (trait anxiety).14 State anxiety relates to the moment of assessment and refers to how a person is feeling at the time. Trait anxiety refers to a stable individual proneness to perceive stressful situations as dangerous or threatening and to respond to such situations with feelings of stress, worry, and discomfort. The understanding of how psychological factors influence susceptibility to vasovagal reflex may be essential for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of syncope. Epidemiological data show that the incidence of reflex syncope increases steeply in the second and third decades of life, especially among females.15 Moreover, there seems to be a link between emotional syncope in early life and coronary events many years later.16 We, therefore, studied anxiety levels and family occurrence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in young women referred to the syncope unit with unexplained transient loss of consciousness (TLOC), and among age-matched randomly selected female controls with or without past history of TLOC.

Patients and methods

Study population and examination

The study was performed between July 2010 and September 2013. A total of 640 women aged 21–40 years were included: 91 consecutive female patients who were referred by primary care physicians or other specialists with history of unexplained TLOC to the University Hospital, Wroclaw, and 549 age-matched women who were recruited among regular and post-graduate university students as controls. Women in the control group were participants in either Emergency Medicine training or Psychology courses at the university. The age range of 21–40 years was selected to conform with that for normal values of state and trait anxiety reported for the Polish population.14 The hospital catchment area covers a total urban population of 1.2 million and is the only centre with a dedicated syncope laboratory. However, there are no local guidelines regarding the investigation of unexplained TLOC, and patients with TLOC may be arbitrarily directed to other hospitals and/or specialists rendering patient coverage likely to be incomplete.

Patients underwent a standard head-up tilt (HUT) protocol, according to current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines employing the Italian protocol.1 The diagnostic criteria were the typical haemodynamic response (sudden onset hypotension and/or bradycardia/asystole) with reproduction of vasovagal reflex-related symptoms including pre- or syncope. Every patient was informed about the purpose of the test, possible syncope, and minimal risks of the method. After giving informed consent, patients filled a questionnaire on personal and family history of syncope, cardiovascular risk factors, as well as a standard STAI (State and Trait Anxiety Inventory) Questionnaire.14 The participants were asked about the number of fainting episodes, age at first faint, and whether fainting had ever been associated with trauma. Those who confirmed regular or occasional current smoking were counted as smokers. Hypertension was defined as current treatment with antihypertensive agents or personal history of untreated hypertension.

Family history of premature CVD was assessed as positive if a first-degree male relative had suffered a myocardial infarction or stroke before the age of 55, or if a first-degree female relative had suffered one before the age of 65. As many participants could not determine the age of first CVD event in their family members, the overall family history of CVD was also assessed as an alternative cardiovascular risk factor, as suggested by previous studies.17 A family history of sudden death was assessed as positive in case of unexplained sudden death among first-degree relatives.

The control group, which was not investigated by HUT, filled either a paper or on-line version of the same study questionnaire at home. The control group was then divided into controls with a history of TLOC and those without a history of TLOC. The discriminating question was ‘have you ever fainted or abruptly lost consciousness?’ Women who had never experienced TLOC were classified as controls without a history of TLOC, whereas women who reported at least one TLOC episode were classified as controls with a history of TLOC. Those who confirmed TLOC as a consequence of trauma, epilepsy, and hypoglycaemia were excluded from the control group. The circumstances of TLOC were explored by additional questions not reported here in detail. Both those with typical vasovagal triggers, such as prolonged standing or instrumentation, and/or prodrome as well as those who could not identify any trigger or prodrome were classified as controls with TLOC history. Retrograde amnesia is a recognized phenomenon in syncope, even in this age group.1 The Institutional Review Board of Wroclaw Medical University gave ethical approval of the study.

State-trait anxiety inventory questionnaire

The state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI) is composed of two separate 20-item self-report scales that measure both state (S-Anxiety) and trait anxiety (T-Anxiety). The S-Anxiety scale assesses how the subject feels ‘right now’, while in the T-Anxiety scale the subject estimates the average anxiety level in different situations. A total score for each scale ranges from 20 to 80, with higher scores indicating a greater anxiety level. The STAI has been shown to possess high reliability and good construct validity in the assessment of anxiety disorders in both adolescents18 and older adults.19 The Polish version of the STAI has the same construction as the original and contains normal values for the Polish population aged 21–79 years. The theoretical validity and reliability indicators for the Polish sample have been previously shown to be satisfactory using this method in both individual diagnoses and scientific empirical research.20

Statistical analysis

The variables were presented as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range for continuous variables, and percentages for categorical variables. The intergroup differences were compared using Student's t, Mann–Whitney U, or Pearson's χ2 tests as appropriate. The relations between dependent categorical variable, i.e. family history of CVD and the presumable predictors of CVD risk, i.e. VVS diagnosis or past TLOC history, were assessed by the appropriate logistic regression models. P < 0.05 was regarded as significant.

Results

Twenty-one of 91 women referred for investigation of syncope were excluded on grounds of history and/or HUT being non-diagnostic for reflex syncope, e.g. typical psychogenic pseudosyncope, arrhythmic syncope, epilepsy, or non-syncopal symptoms only, such as palpitations or dizziness, with the absence of confirmed TLOC. Further, five women were excluded on grounds of negative HUT despite a history suggestive of vasovagal reflex syncope (VVS). Thus, the study group consisted of 65 women. According to the vasovagal syncope international study (VASIS) classification,21 the most frequent HUT-induced pattern of VVS was the mixed one (54%), followed by the cardioinhibitory (37%) and vasodepressor types (9%).

Among 549 controls, 223 (40.6%) reported at least one episode of TLOC, whereas 326 (59.4%) denied any episode. Basic characteristics of the study population stratified according to HUT (study group), or history of TLOC (control group) are presented in Table 1. None of the participants reported diabetes, myocardial infarction, stroke, or any cardiovascular intervention, and only a few women reported arterial hypertension. Number of TLOCs, age at first TLOC, frequency of trauma, and depression were significantly higher in the study group than in controls with history of TLOC. Family history of CVD was more prevalent in the study group compared with controls without history of TLOC (P = 0.006) but did not differ from that in controls with history of TLOC (P = 0.9).

Basic characteristics of study population (n = 614) stratified according to the diagnosis of reflex syncope (study group) or history of TLOC (control group)

| Characteristics . | Study groupa (n = 65) . | Controls with past TLOC historyb (n = 220) . | Controls without past TLOC historyb (n = 320) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29.9 (5.4) | 27.5 (5.8)* | 29.6 (5.8) |

| Smoking (%) | 29.2 | 41.7 | 36.1 |

| Age at the first TLOC (years) | 19.1 (8.7) | 15.4 (5.5)* | – |

| Trauma during TLOC (%) | 38.5 | 7.2* | – |

| Number of TLOCc | 3 (2–10) | 1 (1–2)* | – |

| History of depression (%) | 3.1 | 0* | 2.2 |

| Hypertension (%) | 0 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| Family history of CVD (%) | 32.3 | 31.3 | 16.8* |

| Family history of premature CVD (%) | 16.9 | 19.2 | 11.8 |

| Family history of sudden death (%) | 3.1 | 10.9 | 9.0 |

| Characteristics . | Study groupa (n = 65) . | Controls with past TLOC historyb (n = 220) . | Controls without past TLOC historyb (n = 320) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29.9 (5.4) | 27.5 (5.8)* | 29.6 (5.8) |

| Smoking (%) | 29.2 | 41.7 | 36.1 |

| Age at the first TLOC (years) | 19.1 (8.7) | 15.4 (5.5)* | – |

| Trauma during TLOC (%) | 38.5 | 7.2* | – |

| Number of TLOCc | 3 (2–10) | 1 (1–2)* | – |

| History of depression (%) | 3.1 | 0* | 2.2 |

| Hypertension (%) | 0 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| Family history of CVD (%) | 32.3 | 31.3 | 16.8* |

| Family history of premature CVD (%) | 16.9 | 19.2 | 11.8 |

| Family history of sudden death (%) | 3.1 | 10.9 | 9.0 |

TLOC, transient loss of consciousness; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

aPatients referred to syncope unit with reflex syncope (positive HUT).

bControls with or without personal history of TLOC.

cMedian (interquartile range).

*P < 0.05 vs. study group.

Basic characteristics of study population (n = 614) stratified according to the diagnosis of reflex syncope (study group) or history of TLOC (control group)

| Characteristics . | Study groupa (n = 65) . | Controls with past TLOC historyb (n = 220) . | Controls without past TLOC historyb (n = 320) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29.9 (5.4) | 27.5 (5.8)* | 29.6 (5.8) |

| Smoking (%) | 29.2 | 41.7 | 36.1 |

| Age at the first TLOC (years) | 19.1 (8.7) | 15.4 (5.5)* | – |

| Trauma during TLOC (%) | 38.5 | 7.2* | – |

| Number of TLOCc | 3 (2–10) | 1 (1–2)* | – |

| History of depression (%) | 3.1 | 0* | 2.2 |

| Hypertension (%) | 0 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| Family history of CVD (%) | 32.3 | 31.3 | 16.8* |

| Family history of premature CVD (%) | 16.9 | 19.2 | 11.8 |

| Family history of sudden death (%) | 3.1 | 10.9 | 9.0 |

| Characteristics . | Study groupa (n = 65) . | Controls with past TLOC historyb (n = 220) . | Controls without past TLOC historyb (n = 320) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29.9 (5.4) | 27.5 (5.8)* | 29.6 (5.8) |

| Smoking (%) | 29.2 | 41.7 | 36.1 |

| Age at the first TLOC (years) | 19.1 (8.7) | 15.4 (5.5)* | – |

| Trauma during TLOC (%) | 38.5 | 7.2* | – |

| Number of TLOCc | 3 (2–10) | 1 (1–2)* | – |

| History of depression (%) | 3.1 | 0* | 2.2 |

| Hypertension (%) | 0 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| Family history of CVD (%) | 32.3 | 31.3 | 16.8* |

| Family history of premature CVD (%) | 16.9 | 19.2 | 11.8 |

| Family history of sudden death (%) | 3.1 | 10.9 | 9.0 |

TLOC, transient loss of consciousness; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

aPatients referred to syncope unit with reflex syncope (positive HUT).

bControls with or without personal history of TLOC.

cMedian (interquartile range).

*P < 0.05 vs. study group.

S-Anxiety and T-Anxiety questionnaires were missing in 9 and 13 controls, respectively. Thus, we analysed 605 S-Anxiety and 601 T-anxiety complete questionnaires. The pooled results of female controls with and without TLOC history did not significantly differ from the age-matched population samples used in the validation studies (data not shown). As can be seen in Table 2, state-anxiety level was higher in patients undergoing HUT and diagnosed with VVS (42.4 ± 9.3), compared with both those with and without TLOC history, although the state-anxiety level was significantly higher in controls with TLOC history compared with controls without TLOC history (38.3 ± 10.2 vs. 35.9 ± 9.8, P = 0.007). Consequently, an incremental state-anxiety pattern was observed from the lowest level among controls without history of TLOC, higher among those with self-reported TLOC, to the highest level among those undergoing HUT due to unexplained TLOC. Further, 57% of patients with reflex syncope demonstrated more than moderate levels of state anxiety compared with only 28% of controls without a history of TLOC. However, trait-anxiety level did not differ between patients with reflex syncope (42.7 ± 8.4) and controls with a history of TLOC (42.4 ± 8.4), in contrast to that in controls without a history of TLOC, which was significantly lower (39.7 ± 8.5; P < 0.01). Four of 10 patients with reflex syncope demonstrated high trait-anxiety levels compared with only 19% of controls without a history of TLOC (Table 2).

State and trait anxiety assessed in the study population (n = 605) stratified according to the diagnosis of reflex syncope (study group) or history of TLOC (control group)

| Anxiety level . | Study groupa (n = 65) . | Controls with past TLOC historyb (n = 220) . | Controls without past TLOC historyb (n = 320) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| State | |||

| Raw (mean ± SD) | 42.4 ± 9.3 | 38.3 ± 10.2*,*** | 35.9 ± 9.8** |

| Low (1–4th decile) [n(%)] | 11 (17) | 75 (34) | 128 (40) |

| Moderate (5–6th decile) [n(%)] | 17 (26) | 64 (27) | 102 (32) |

| High (7–10th decile) [n(%)] | 37 (57) | 81 (39)* | 90 (28)** |

| Trait | |||

| Raw (mean ± SD) | 42.7 ± 8.4 | 42.4 ± 8.4*** | 39.7 ± 8.5* |

| Low (1–4th decile) [n(%)] | 21 (32) | 86 (39) | 170 (54) |

| Moderate (5–6th decile) [n(%)] | 19 (29) | 63 (29) | 86 (27) |

| High (7–10th decile) [n(%)] | 25 (39) | 70 (32)*** | 61 (19)** |

| Anxiety level . | Study groupa (n = 65) . | Controls with past TLOC historyb (n = 220) . | Controls without past TLOC historyb (n = 320) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| State | |||

| Raw (mean ± SD) | 42.4 ± 9.3 | 38.3 ± 10.2*,*** | 35.9 ± 9.8** |

| Low (1–4th decile) [n(%)] | 11 (17) | 75 (34) | 128 (40) |

| Moderate (5–6th decile) [n(%)] | 17 (26) | 64 (27) | 102 (32) |

| High (7–10th decile) [n(%)] | 37 (57) | 81 (39)* | 90 (28)** |

| Trait | |||

| Raw (mean ± SD) | 42.7 ± 8.4 | 42.4 ± 8.4*** | 39.7 ± 8.5* |

| Low (1–4th decile) [n(%)] | 21 (32) | 86 (39) | 170 (54) |

| Moderate (5–6th decile) [n(%)] | 19 (29) | 63 (29) | 86 (27) |

| High (7–10th decile) [n(%)] | 25 (39) | 70 (32)*** | 61 (19)** |

aPatients referred to syncope unit with reflex syncope (positive HUT).

bControls with or without past history of TLOC.

*P < 0.01 vs. study group.

**P < 0.001 vs. study group.

***P < 0.01 vs. controls without past TLOC history.

State and trait anxiety assessed in the study population (n = 605) stratified according to the diagnosis of reflex syncope (study group) or history of TLOC (control group)

| Anxiety level . | Study groupa (n = 65) . | Controls with past TLOC historyb (n = 220) . | Controls without past TLOC historyb (n = 320) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| State | |||

| Raw (mean ± SD) | 42.4 ± 9.3 | 38.3 ± 10.2*,*** | 35.9 ± 9.8** |

| Low (1–4th decile) [n(%)] | 11 (17) | 75 (34) | 128 (40) |

| Moderate (5–6th decile) [n(%)] | 17 (26) | 64 (27) | 102 (32) |

| High (7–10th decile) [n(%)] | 37 (57) | 81 (39)* | 90 (28)** |

| Trait | |||

| Raw (mean ± SD) | 42.7 ± 8.4 | 42.4 ± 8.4*** | 39.7 ± 8.5* |

| Low (1–4th decile) [n(%)] | 21 (32) | 86 (39) | 170 (54) |

| Moderate (5–6th decile) [n(%)] | 19 (29) | 63 (29) | 86 (27) |

| High (7–10th decile) [n(%)] | 25 (39) | 70 (32)*** | 61 (19)** |

| Anxiety level . | Study groupa (n = 65) . | Controls with past TLOC historyb (n = 220) . | Controls without past TLOC historyb (n = 320) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| State | |||

| Raw (mean ± SD) | 42.4 ± 9.3 | 38.3 ± 10.2*,*** | 35.9 ± 9.8** |

| Low (1–4th decile) [n(%)] | 11 (17) | 75 (34) | 128 (40) |

| Moderate (5–6th decile) [n(%)] | 17 (26) | 64 (27) | 102 (32) |

| High (7–10th decile) [n(%)] | 37 (57) | 81 (39)* | 90 (28)** |

| Trait | |||

| Raw (mean ± SD) | 42.7 ± 8.4 | 42.4 ± 8.4*** | 39.7 ± 8.5* |

| Low (1–4th decile) [n(%)] | 21 (32) | 86 (39) | 170 (54) |

| Moderate (5–6th decile) [n(%)] | 19 (29) | 63 (29) | 86 (27) |

| High (7–10th decile) [n(%)] | 25 (39) | 70 (32)*** | 61 (19)** |

aPatients referred to syncope unit with reflex syncope (positive HUT).

bControls with or without past history of TLOC.

*P < 0.01 vs. study group.

**P < 0.001 vs. study group.

***P < 0.01 vs. controls without past TLOC history.

The relative probability of positive family history of CVD among young women diagnosed with VVS (n = 65), age-matched controls with past history of TLOC) (Pos controls, n = 223), and both groups pooled (TLOC pooled) compared with controls without past history of TLOC (n = 326) as a reference. The age-adjusted logistic regression model was applied. Premature CVD was defined as the occurrence of CVD (myocardial infarction or stroke) in a first-degree male relative before the age of 55, or in a first-degree female relative before the age of 65.

The history of TLOC in controls was associated with a family history of premature CVD (OR, 95% CI 1.8, 1.0–3.1; P = 0.037), in contrast to the VVS group (OR, 95% CI 1.6, 0.7–3.3, P = 0.27). However, as shown in Figure 1, after pooling all individuals with prevalent TLOC, i.e. those diagnosed with VVS and controls with a history of TLOC, the occurrence of either confirmed or probable VVS predicted both overall and premature CVD among first-grade relatives. The relationship between family history of sudden unexplained death and TLOC in both the patients and the controls with a history of TLOC was not significant for either subgroup (all P-values >0.2). Using the multivariate-adjusted logistic regression model, we were unable to show a significant relationship between either state- or trait-anxiety levels and family history of CVD (all P-values >0.2).

Discussion

In this study, the state- and trait-anxiety level was higher among investigated reflex syncope patients but only when compared with control individuals who had never experienced TLOC. In contrast, those controls who reported at least one TLOC demonstrated as high level of trait anxiety as those with VVS. Thus, an increased anxiety level may be a component of the vasovagal reflex-related phenotype, regardless of the number of TLOCs and their severity. However, the causal relationship between syncope and anxiety is difficult to assess because recurrent TLOC may provoke substantial anxiety and make the patient seek medical attention more often compared with unaffected age-matched individuals.23

Levels of anxiety, both state and trait, had no relationship with a family history of CVD but syncope, proven to be vasovagal in nature or assumed to be so in the positive control group had an important relationship with CVD. Anxiety levels are, therefore, considered not to be responsible for the demonstrated CVD relationship. Other possible mechanisms have not been tested in this study but they should be the subject of further work.

The higher state anxiety among the vasovagal reflex patients than among controls with a history of TLOC may be explained by the stressful pre-test situation and expectations of the test outcome. Reports regarding the level of anxiety in vasovagal patients are sparse and mainly refer to those who sought medical help.23–25 Patients with VVS demonstrate a higher frequency of psychiatric disorders than patients with cardiac arrhythmias.25 Among patients with unexplained syncope, anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric finding.26 However, patients with unexplained syncope and negative HUT exhibit even higher levels of psychological distress than those with positive HUT.8

In young females with a history of TLOC, the dominant TLOC aetiology was from the history most likely to be reflex in origin.1 However, even if some controls reported TLOC of other than vasovagal reflex aetiology, the above-cited data suggest that the average anxiety level would be higher rather than lower among patients in whom VVS is the confirmed diagnosis. Indeed, in this study trait-anxiety level did not differ between patients with vasovagal reflex and controls with past history of TLOC.

The age at first syncope was higher in patients with VVS than in controls with a history of TLOC, 19 vs. 15 years. While this is a statistically significant difference, these two ages fall well within the first peak of incidence of reflex syncope according to Dutch epidemiological data.3,15 Also shown in Table 1 is the high level of trauma due to syncope found in patients compared with controls with a history of TLOC but it falls within the published range of other work on the incidence of trauma in syncope.27,28

The high prevalence of CVD in families of syncopal patients is in concordance with our previous report on association between the prevalence of vasovagal syncope in the first decades of life and the incidence of cardiovascular events in later life.16 This relationship was independent of higher anxiety levels, also suggesting that additional mechanisms are involved. A high prevalence of syncope and CVD in families of patients with reflex syncope has been recently confirmed by other authors and may reflect shared hereditary susceptibility to both VVS and cardiovascular morbidity.29 Further studies on the prognostic importance of syncope in relation to CVD and the pathophysiological links between them are needed.

Limitations

There are certain limitations to this study. First, it only addressed females implying that the data cannot be extrapolated to males. Secondly, the control data are historical and, despite the diligence in collection, are likely to contain some imprecision. Thirdly, the study group was relatively small but sufficient to permit analysis. Fourthly, the selection of controls from a highly educated group may be prejudicial to the applicability of the findings to a general population.

Conclusions

State- and trait-anxiety levels were higher in patients with VVS than in controls without a history of TLOC.

Family history of CVD was more prevalent in both young women with VVS and controls with a history of TLOC.

However, a higher anxiety level was not related to family history of CVD and other mechanisms should be considered as a link between syncope and cardiovascular events.

Funding

This study was supported by grant from the Wroclaw Medical University number ST-384.

Conflicts of interest: none declared.