-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Thomas J. McGarry, Rajeev Joshi, Hiro Kawata, Jigar Patel, Gregory Feld, Ulrika M. Birgersdotter-Green, Victor Pretorius, Pocket infections of cardiac implantable electronic devices treated by negative pressure wound therapy, EP Europace, Volume 16, Issue 3, March 2014, Pages 372–377, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eut305

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Managing an infection of the pocket of a cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) is frequently challenging. The wound is often treated with a drain or wet-to-dry dressings that allow healing by secondary intention. Such treatment can prolong the hospital stay and can frequently result in a disfiguring scar. Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has been frequently used to promote the healing of chronic or infected surgical wounds. Here we describe the first series of 28 patients in which NPWT was successfully used to treat CIED pocket infections.

After removal of the CIED and debridement of the pocket, a negative pressure of 125 mmHg continuously applied to the wound through an occlusive dressing. Negative pressure wound therapy was continued for a median of 5 days (range 2–15 days) and drained an average of 260 mL sero-sanguineous fluid (range 35–970 mL). At the conclusion of NPWT, delayed primary closure of the pocket was performed with 1-0 prolene mattress sutures. The median length of stay after CIED extraction was 11.0 days (range 2–43 days). Virtually all infected pockets healed without complications and without evidence of recurrent infection over a median follow-up of 49 days (range 10–752 days). One patient developed a recurrent infection when NPWT was discontinued prematurely and a new device was implanted at the infected site.

We conclude that NPWT is a safe and effective means to promote healing of infected pockets with a low incidence of recurrent infection and a satisfactory cosmetic result.

We report the first series of cases in which negative pressure wound therapy was routinely employed to treat CIED pocket infections after device removal and lead extraction.

Negative pressure wound therapy promotes rapid wound healing, entails few dressing changes, and gives a pleasing cosmetic result with a low risk of recurrent infection.

Placement of a temporary pacemaker at the time of device extraction does not seem to increase the risk of recurrent infection.

Negative pressure wound therapy may offer advantages over standard methods of treating a pocket infection, including placement of a drain or allowing the wound to heal by secondary intention.

Introduction

Infection of cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) is a growing clinical problem.1 Implantation of CIEDs is increasing at a rate of ∼5% per year in the United States, as the population ages and indications for device implantation expand.2 The rate of CIED infection is growing even more rapidly than the rate of implantation,3–6 probably because devices with more leads are being used in older patients with more risk factors for infection. The mainstays of treatment are complete removal of the infected device and a prolonged course of appropriate antibiotic therapy.7,8 The management of CIED infection remains, however, a challenging clinical problem. Infection of a CIED carries about a 5% mortality risk, prolongs hospital stay, and adds significantly to health care costs.9 The surgical mortality associated with extraction of a CIED is greatly increased in the presence of an active infection.10,11

A particularly problematic area in the management of CIED infection is the treatment of an infected pocket after device extraction. Traditionally, infected wounds are treated either with a drain or with wet-to-dry dressing changes and allowed to heal by secondary intention. There is debate as to whether the infected pocket site should be closed before insertion of a new device and whether the generator capsule should be completely debrided. Closure of the wound might trap bacteria under the skin, while leaving the wound open might leave it vulnerable to external infection.

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has been used to treat many different types of chronic wounds that are difficult to heal by primary closure. Healing may be problematic because of the wound's anatomic site, because of the presence of an infection, or because of patient factors like obesity or diabetes mellitus. During NPWT continuous suction is applied to a sealed, airtight wound.12,13 NPWT removes edema fluid, exudate, and debris from the wound bed. It is also thought to increase blood flow to the wound, to reduce the bacterial count, and to promote the formation of granulation tissue by stimulating cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and the elaboration of growth factors.14 NPWT has been successfully employed to treat laparotomy wounds, open bone fractures, lower extremity trauma, split thickness skin grafts, and diabetic foot ulcers.15–19 In cardiac surgery NPWT has been extensively used to treat deep surgical wound infections and post-sternotomy mediastinitis.20,21 Retrospective analyses suggest that in these infections NPWT reduces mortality and lowers the re-infection rate. In a randomized multicenter trial, NPWT was compared to standard therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot infections after trans-metatarsal amputation.22 NPWT was found to significantly increase the proportion of wounds that healed successfully and to speed the rate of healing.

A total of 10 case reports describing the use of NPWT to treat CIED pocket infections have been published.23–25 In these cases, NPWT was reserved for unusual situations where either the device and leads were not completely extracted or wide debridement of the pocket made primary closure impossible. NPWT was applied on an inpatient basis for a prolonged period of time (20–60 days), and one patient out of the 10 developed a late re-infection.

In our centre, we have routinely used NPWT to treat pocket infections after device and lead extraction. Here, we report our experience with the first 28 patients. We find that NPWT is safe and effective, has a low reinfection rate, and is associated with a short hospital stay. This is the first report of the routine use of NPWT in the treatment of CIED pocket infections.

Methods

Patient characteristics

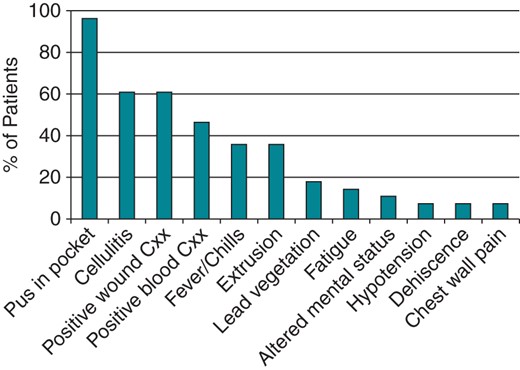

NPWT devices were implanted in 28 successive patients who showed obvious evidence of a pocket infection at the time of device extraction (Table 1). Subjects were predominantly male (70%) and elderly (median age 69 years, range 30–93 years). Patients had an average of 1.8 risk factors for device infection (diabetes, chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, generator change, or anticoagulation7) and an average of 2.5 leads. In 9 patients (32%) the infection occurred within 3 months of the latest generator implantation (median 32 days, range 8–70 days). In the other 19 patients (68%) infection occurred more than 3 months after the last implantation (median 39 months, range 6 months to 12 years). In 2 patients infection developed about 2 weeks after trauma to the pulse generator site, and in 3 patients the infection appeared to have been seeded from another site. The most common signs and symptoms of infection were frank pus in the pocket at the time of extraction, cellulitis over the implantation site, fever or chills, and extrusion of the device through the skin (Figure 1). Other symptoms included chest pain, fatigue, wound dehiscence, altered mental status, and hypotension. Acute infection was diagnosed in 16 patients (57%), which we define as presenting with infectious symptoms within 1 month of symptom onset (average 2 weeks, range 1 day to 1 month). Chronic infection was diagnosed in 12 patients (43%), which we define as presenting with an asymptomatic erosion of device hardware through the skin (7 patients) or presenting more than 1 month after symptom onset (5 patients, range 1–4 months).

| Pt . | Age/sex . | Device type . | Lead # . | Time since implant . | NPWT duration (days) . | NPWT drainage (mL) . | LOS post-Op (days) . | Time to re-implant (days) . | Infection-free follow-up (days) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 75 M | BiV-ICD | 3 | 15 days | ND | ND | 9 | 6 | 752 |

| 2 | 68 M | ICD | 1 | 4 years | 5 | 345 | 6 | 47 | 65 |

| 3 | 43 M | DC PM | 3 | 3 years | 15 | 580 | 16 | 15 | 48 |

| 4 | 69 F | BiV-ICD | 4 | 1.0 years | 9 | 70 | 7 | 47 | 129 |

| 5 | 73 M | BiV-ICD | 4 | 2 months | 4 | 605 | 7 | 4 | 10 |

| 6 | 70 M | DC PM | 2 | 15 days | 5 | 100 | 6 | 20 | 142 |

| 7 | 79 M | ICD | 2 | 25 days | 4 | 170 | 6 | ND | 17 |

| 8 | 65 M | DC PM | 4 | 3 years | 6 | 150 | 12 | ND | 11 |

| 9 | 64 M | BiV-ICD | 4 | 2.3 years | 5 | 90 | 15 | 14 | – |

| 10 | 30 M | DC PM | 2 | 6 years | 3 | 65 | 6 | No plan | 38 |

| 11 | 43 F | BiV-ICD | 3 | 8 days | 3 | NR | 4 | 24 | 192 |

| 12 | 67 F | ICD | 3 | 6 months | 6 | NR | 12 | 55 | 437 |

| 13 | 93 F | DC PM | 2 | 6 months | 6 | 130 | 13 | 9 | 413 |

| 14 | 70 M | ICD | 2 | 4.0 years | 2 | 125 | 2 | ND | 27 |

| 15 | 52 M | DC PM | 3 | 53 day | ND | 40 | 14 | 10 | 400 |

| 16 | 85 M | DC PM | 2 | 1.6 years | 4 | 100 | 10 | 7 | 294 |

| 17 | 89 F | DC PM | 2 | 12 years | 3 | 35 | 9 | 8 | 18 |

| 18 | 75 F | BiV-ICD | 3 | 2.9 years | 7 | 485 | 9 | 3 | 10 |

| 19 | 53 M | ICD | 2 | 2 months | 13 | 180 | 26 | 24 | 26 |

| 20 | 55 M | ICD | 2 | 40 days | 3 | 80 | 10 | 8 | 66 |

| 21 | 83 F | DC PM | 2 | 5.2 years | 6 | 310 | 8 | 47 | 49 |

| 22 | 86 M | ICD | 3 | 3.3 years | 7 | 480 | 9 | ND | 78 |

| 23 | 70 F | DC PM | 2 | 1.0 years | 4 | 40 | 4 | No plan | 85 |

| 24 | 82 M | DC PM | 2 | 11 months | 4 | 370 | 4 | No plan | 21 |

| 25 | 58 F | ICD | 2 | 4.9 years | 7 | 615 | 43 | No plan | 133 |

| 26 | 55 M | ICD | 2 | 2.7 years | 7 | 70 | 13 | 43 | 57 |

| 27 | 58 M | BiV-ICD | 3 | 7 months | 4 | (1895)a | 17 | ND | ND |

| 28 | 56 M | ICD | 2 | 2.3 years | >11 | >970 | 11 | ND | ND |

| Pt . | Age/sex . | Device type . | Lead # . | Time since implant . | NPWT duration (days) . | NPWT drainage (mL) . | LOS post-Op (days) . | Time to re-implant (days) . | Infection-free follow-up (days) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 75 M | BiV-ICD | 3 | 15 days | ND | ND | 9 | 6 | 752 |

| 2 | 68 M | ICD | 1 | 4 years | 5 | 345 | 6 | 47 | 65 |

| 3 | 43 M | DC PM | 3 | 3 years | 15 | 580 | 16 | 15 | 48 |

| 4 | 69 F | BiV-ICD | 4 | 1.0 years | 9 | 70 | 7 | 47 | 129 |

| 5 | 73 M | BiV-ICD | 4 | 2 months | 4 | 605 | 7 | 4 | 10 |

| 6 | 70 M | DC PM | 2 | 15 days | 5 | 100 | 6 | 20 | 142 |

| 7 | 79 M | ICD | 2 | 25 days | 4 | 170 | 6 | ND | 17 |

| 8 | 65 M | DC PM | 4 | 3 years | 6 | 150 | 12 | ND | 11 |

| 9 | 64 M | BiV-ICD | 4 | 2.3 years | 5 | 90 | 15 | 14 | – |

| 10 | 30 M | DC PM | 2 | 6 years | 3 | 65 | 6 | No plan | 38 |

| 11 | 43 F | BiV-ICD | 3 | 8 days | 3 | NR | 4 | 24 | 192 |

| 12 | 67 F | ICD | 3 | 6 months | 6 | NR | 12 | 55 | 437 |

| 13 | 93 F | DC PM | 2 | 6 months | 6 | 130 | 13 | 9 | 413 |

| 14 | 70 M | ICD | 2 | 4.0 years | 2 | 125 | 2 | ND | 27 |

| 15 | 52 M | DC PM | 3 | 53 day | ND | 40 | 14 | 10 | 400 |

| 16 | 85 M | DC PM | 2 | 1.6 years | 4 | 100 | 10 | 7 | 294 |

| 17 | 89 F | DC PM | 2 | 12 years | 3 | 35 | 9 | 8 | 18 |

| 18 | 75 F | BiV-ICD | 3 | 2.9 years | 7 | 485 | 9 | 3 | 10 |

| 19 | 53 M | ICD | 2 | 2 months | 13 | 180 | 26 | 24 | 26 |

| 20 | 55 M | ICD | 2 | 40 days | 3 | 80 | 10 | 8 | 66 |

| 21 | 83 F | DC PM | 2 | 5.2 years | 6 | 310 | 8 | 47 | 49 |

| 22 | 86 M | ICD | 3 | 3.3 years | 7 | 480 | 9 | ND | 78 |

| 23 | 70 F | DC PM | 2 | 1.0 years | 4 | 40 | 4 | No plan | 85 |

| 24 | 82 M | DC PM | 2 | 11 months | 4 | 370 | 4 | No plan | 21 |

| 25 | 58 F | ICD | 2 | 4.9 years | 7 | 615 | 43 | No plan | 133 |

| 26 | 55 M | ICD | 2 | 2.7 years | 7 | 70 | 13 | 43 | 57 |

| 27 | 58 M | BiV-ICD | 3 | 7 months | 4 | (1895)a | 17 | ND | ND |

| 28 | 56 M | ICD | 2 | 2.3 years | >11 | >970 | 11 | ND | ND |

LOS, length of stay; M, male; F, female; DC PM, dual chamber pacemaker; ICD, implantable cardiac defibrillator; Bi-V, bi-ventricular pacemaker; ND, no data; no plan, CIED re-implantation is not planned.

aThis patient had bleeding that was drained by NPWT. His drainage is not included in the average.

| Pt . | Age/sex . | Device type . | Lead # . | Time since implant . | NPWT duration (days) . | NPWT drainage (mL) . | LOS post-Op (days) . | Time to re-implant (days) . | Infection-free follow-up (days) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 75 M | BiV-ICD | 3 | 15 days | ND | ND | 9 | 6 | 752 |

| 2 | 68 M | ICD | 1 | 4 years | 5 | 345 | 6 | 47 | 65 |

| 3 | 43 M | DC PM | 3 | 3 years | 15 | 580 | 16 | 15 | 48 |

| 4 | 69 F | BiV-ICD | 4 | 1.0 years | 9 | 70 | 7 | 47 | 129 |

| 5 | 73 M | BiV-ICD | 4 | 2 months | 4 | 605 | 7 | 4 | 10 |

| 6 | 70 M | DC PM | 2 | 15 days | 5 | 100 | 6 | 20 | 142 |

| 7 | 79 M | ICD | 2 | 25 days | 4 | 170 | 6 | ND | 17 |

| 8 | 65 M | DC PM | 4 | 3 years | 6 | 150 | 12 | ND | 11 |

| 9 | 64 M | BiV-ICD | 4 | 2.3 years | 5 | 90 | 15 | 14 | – |

| 10 | 30 M | DC PM | 2 | 6 years | 3 | 65 | 6 | No plan | 38 |

| 11 | 43 F | BiV-ICD | 3 | 8 days | 3 | NR | 4 | 24 | 192 |

| 12 | 67 F | ICD | 3 | 6 months | 6 | NR | 12 | 55 | 437 |

| 13 | 93 F | DC PM | 2 | 6 months | 6 | 130 | 13 | 9 | 413 |

| 14 | 70 M | ICD | 2 | 4.0 years | 2 | 125 | 2 | ND | 27 |

| 15 | 52 M | DC PM | 3 | 53 day | ND | 40 | 14 | 10 | 400 |

| 16 | 85 M | DC PM | 2 | 1.6 years | 4 | 100 | 10 | 7 | 294 |

| 17 | 89 F | DC PM | 2 | 12 years | 3 | 35 | 9 | 8 | 18 |

| 18 | 75 F | BiV-ICD | 3 | 2.9 years | 7 | 485 | 9 | 3 | 10 |

| 19 | 53 M | ICD | 2 | 2 months | 13 | 180 | 26 | 24 | 26 |

| 20 | 55 M | ICD | 2 | 40 days | 3 | 80 | 10 | 8 | 66 |

| 21 | 83 F | DC PM | 2 | 5.2 years | 6 | 310 | 8 | 47 | 49 |

| 22 | 86 M | ICD | 3 | 3.3 years | 7 | 480 | 9 | ND | 78 |

| 23 | 70 F | DC PM | 2 | 1.0 years | 4 | 40 | 4 | No plan | 85 |

| 24 | 82 M | DC PM | 2 | 11 months | 4 | 370 | 4 | No plan | 21 |

| 25 | 58 F | ICD | 2 | 4.9 years | 7 | 615 | 43 | No plan | 133 |

| 26 | 55 M | ICD | 2 | 2.7 years | 7 | 70 | 13 | 43 | 57 |

| 27 | 58 M | BiV-ICD | 3 | 7 months | 4 | (1895)a | 17 | ND | ND |

| 28 | 56 M | ICD | 2 | 2.3 years | >11 | >970 | 11 | ND | ND |

| Pt . | Age/sex . | Device type . | Lead # . | Time since implant . | NPWT duration (days) . | NPWT drainage (mL) . | LOS post-Op (days) . | Time to re-implant (days) . | Infection-free follow-up (days) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 75 M | BiV-ICD | 3 | 15 days | ND | ND | 9 | 6 | 752 |

| 2 | 68 M | ICD | 1 | 4 years | 5 | 345 | 6 | 47 | 65 |

| 3 | 43 M | DC PM | 3 | 3 years | 15 | 580 | 16 | 15 | 48 |

| 4 | 69 F | BiV-ICD | 4 | 1.0 years | 9 | 70 | 7 | 47 | 129 |

| 5 | 73 M | BiV-ICD | 4 | 2 months | 4 | 605 | 7 | 4 | 10 |

| 6 | 70 M | DC PM | 2 | 15 days | 5 | 100 | 6 | 20 | 142 |

| 7 | 79 M | ICD | 2 | 25 days | 4 | 170 | 6 | ND | 17 |

| 8 | 65 M | DC PM | 4 | 3 years | 6 | 150 | 12 | ND | 11 |

| 9 | 64 M | BiV-ICD | 4 | 2.3 years | 5 | 90 | 15 | 14 | – |

| 10 | 30 M | DC PM | 2 | 6 years | 3 | 65 | 6 | No plan | 38 |

| 11 | 43 F | BiV-ICD | 3 | 8 days | 3 | NR | 4 | 24 | 192 |

| 12 | 67 F | ICD | 3 | 6 months | 6 | NR | 12 | 55 | 437 |

| 13 | 93 F | DC PM | 2 | 6 months | 6 | 130 | 13 | 9 | 413 |

| 14 | 70 M | ICD | 2 | 4.0 years | 2 | 125 | 2 | ND | 27 |

| 15 | 52 M | DC PM | 3 | 53 day | ND | 40 | 14 | 10 | 400 |

| 16 | 85 M | DC PM | 2 | 1.6 years | 4 | 100 | 10 | 7 | 294 |

| 17 | 89 F | DC PM | 2 | 12 years | 3 | 35 | 9 | 8 | 18 |

| 18 | 75 F | BiV-ICD | 3 | 2.9 years | 7 | 485 | 9 | 3 | 10 |

| 19 | 53 M | ICD | 2 | 2 months | 13 | 180 | 26 | 24 | 26 |

| 20 | 55 M | ICD | 2 | 40 days | 3 | 80 | 10 | 8 | 66 |

| 21 | 83 F | DC PM | 2 | 5.2 years | 6 | 310 | 8 | 47 | 49 |

| 22 | 86 M | ICD | 3 | 3.3 years | 7 | 480 | 9 | ND | 78 |

| 23 | 70 F | DC PM | 2 | 1.0 years | 4 | 40 | 4 | No plan | 85 |

| 24 | 82 M | DC PM | 2 | 11 months | 4 | 370 | 4 | No plan | 21 |

| 25 | 58 F | ICD | 2 | 4.9 years | 7 | 615 | 43 | No plan | 133 |

| 26 | 55 M | ICD | 2 | 2.7 years | 7 | 70 | 13 | 43 | 57 |

| 27 | 58 M | BiV-ICD | 3 | 7 months | 4 | (1895)a | 17 | ND | ND |

| 28 | 56 M | ICD | 2 | 2.3 years | >11 | >970 | 11 | ND | ND |

LOS, length of stay; M, male; F, female; DC PM, dual chamber pacemaker; ICD, implantable cardiac defibrillator; Bi-V, bi-ventricular pacemaker; ND, no data; no plan, CIED re-implantation is not planned.

aThis patient had bleeding that was drained by NPWT. His drainage is not included in the average.

Presenting symptoms in CIED infections. The percentage of patients with each symptom is graphed. Cxx, cultures.

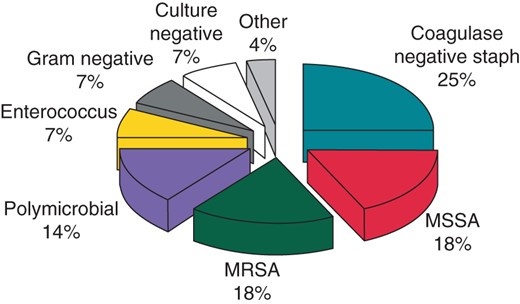

Most patients (26 of 28, 93%) had positive blood, wound, or lead tip cultures. Staphylococcal species were the most common pathogens. They were cultured from 21 patients (75%) and were evenly divided between methicillin-sensitive, methicillin-resistant, and coagulase-negative species (Figure 2). Two patients presented with persistent enterococcal bacteremia. Other organisms included Pseudomonas aeruginosa, E. coli, Enterobacter species, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Acute infections were predominantly caused by methicillin-sensitive or methicillin-resistant staphylococci (12 of 16 patients, 75%). Chronic infections were predominantly caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci or gram negative bacilli (8 of 12 patients, 67%). Five patients had vegetations seen on either the leads or the heart valves by trans-esophageal echocardiography.

Procedure

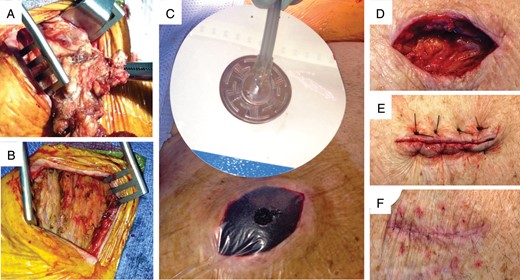

Extraction procedures were performed an average of 4.9 days after the patient's initial presentation for the infection (median 4 days, range 0–20 days). After removal of the infected leads and the pulse generator, the pocket was copiously irrigated with antibiotic saline (cefazolin 1 g/L in normal saline) and extensively debrided to remove all infected tissue, foreign material, and pus. We performed a complete capsulectomy because the capsule is relatively avascular and is often seeded with bacteria26 (Figure 3A and 3B). Care was taken to ensure complete hemostasis using electrocautery, and a figure-of-eight 2-0 Vicryl suture was placed in the muscle overlying the sites where the leads entered the venous system. Our procedure for inserting the NPWT device was described previously.27 Briefly, after re-irrigating the pocket with antibiotic saline, the skin incision was modified to form a lenticular shape and then packed with a GranuForm™ sponge that was trimmed to be about 25% smaller than the wound margins (Figure 3C). The purpose of the sponge is to distribute the negative pressure throughout the entire wound bed and to prevent the end of the pressure tubing from becoming occluded. A silver-impregnated sponge is available, which is thought to have antimicrobial activity.

Surgical technique for NPWT. (A) Excision of the infected capsule. (B) The pocket after complete capsulectomy and debridement. (C) Application of NPWT. The wound has been packed with a sponge and covered with an occlusive dressing with a hole. The suction tube is attached to an adhesive support. See text for details. (D) The wound after completion of NPWT. (E) Closure of the wound with prolene sutures. (F) The healed wound one month after discontinuation of NPWT.

The entire wound was covered with an occlusive dressing and a drainage tube was inserted through a hole in the occlusive dressing over the centre of the sponge. A continuous negative pressure of 125 mmHg was applied using a wound vacuum device (ActiV.A.C. System, KCI Medical, see Supplementary data online Figure S1). The negative suction pressure did not cause increased patient discomfort. The dressing was changed every 72–96 h, and NPWT was discontinued when drainage fluid became clear, the volume dropped to less than 25 cc per day, and the wound bed became covered with fresh granulation tissue. Delayed primary closure of the wound was then performed employing 3 or 4 1–0 Prolene mattress sutures (Figure 3D–F). Patients were usually discharged with the prolene sutures in place, and they were removed in clinic after approximately 2 weeks.

In 11 patients who were felt to be pacemaker-dependent (39%), a temporary permanent pacemaker was inserted at the time of extraction.28 In these cases a pacing lead was placed percutaneously through the contralateral jugular vein and the pulse generator was attached and placed in an extracorporeal position28 Three patients were fitted with an external wearable defibrillator (Life Vest, Zoll Medical Corporation) until their implantable cardiac defibrillator was re-implanted.29 Patients were treated with intravenous or oral antibiotics for an average of 4.0 weeks after extraction (median 4 weeks, range 1–8 weeks), according to the advice of the Infectious Disease Service. In patients who presented with bacteremia, implantation of the new device was delayed until 2 weeks after the last positive blood culture, in accordance with published guidelines.7

Results

The median duration of NPWT was 5 days (Table 2; range 2–15 days), and the median total volume of sero-sanguineous fluid removed was 260 ml (range 35–970 ml). Patients were discharged from the hospital an average of 11.0 days (range 2–43 days) after device extraction. The length of the hospital stay was often dictated by factors unrelated to the duration of NPWT. The average length of stay after NPWT was discontinued was 4.5 days with a median of 2.5 days and a range of 0–29 days. Three patients were transferred to another facility; the others were discharged to home. Devices were re-implanted in the contralateral hemithorax a median of 15 days after extraction (range 3–55 days).

| . | Average . | Median . | Range . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leads | 2.5 | 2 | 1–4 |

| Age of device | 820 days | 490 days | 8 days–6 years |

| NPWT duration | 5.7 days | 5.0 days | 1–15 days |

| NPWT drainage | 260 mL | 140 mL | 35–970 mL |

| Post-operative LOS | 11.0 days | 9 days | 2–43 days |

| Time to re-implant | 22 days | 15 days | 3–55 days |

| Infection-free follow-up | 116 days | 49 days | 10–752 days |

| . | Average . | Median . | Range . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leads | 2.5 | 2 | 1–4 |

| Age of device | 820 days | 490 days | 8 days–6 years |

| NPWT duration | 5.7 days | 5.0 days | 1–15 days |

| NPWT drainage | 260 mL | 140 mL | 35–970 mL |

| Post-operative LOS | 11.0 days | 9 days | 2–43 days |

| Time to re-implant | 22 days | 15 days | 3–55 days |

| Infection-free follow-up | 116 days | 49 days | 10–752 days |

| . | Average . | Median . | Range . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leads | 2.5 | 2 | 1–4 |

| Age of device | 820 days | 490 days | 8 days–6 years |

| NPWT duration | 5.7 days | 5.0 days | 1–15 days |

| NPWT drainage | 260 mL | 140 mL | 35–970 mL |

| Post-operative LOS | 11.0 days | 9 days | 2–43 days |

| Time to re-implant | 22 days | 15 days | 3–55 days |

| Infection-free follow-up | 116 days | 49 days | 10–752 days |

| . | Average . | Median . | Range . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leads | 2.5 | 2 | 1–4 |

| Age of device | 820 days | 490 days | 8 days–6 years |

| NPWT duration | 5.7 days | 5.0 days | 1–15 days |

| NPWT drainage | 260 mL | 140 mL | 35–970 mL |

| Post-operative LOS | 11.0 days | 9 days | 2–43 days |

| Time to re-implant | 22 days | 15 days | 3–55 days |

| Infection-free follow-up | 116 days | 49 days | 10–752 days |

The median follow-up period was 49 days (range 10–752 days). In all but one of our 28 patients, the wound healed completely, without complications, and without evidence of residual infection. We observed no re-infections in the 11 pacemaker-dependent patients in whom a ‘temporary permanent’ pacemaker had been inserted through the contralateral internal jugular vein at the time of extraction.28

In the patient who developed a recurrent infection (#9), the etiologic organism was E. faecalis and NPWT had been maintained for only 2 days. NPWT was discontinued prematurely after the patient was transferred to a different hospital. Two weeks later, this patient had a new device implanted at the previously infected site because the contralateral subclavian vein could not be accessed. Recurrent infection was discovered 2 months after re-implantation, when the pocket was explored for a lead revision. We speculate that in this case the original infection had not been adequately treated. In another case (#15) the patient developed constitutional symptoms 3 months after a new device was implanted in the contralateral hemithorax. He was found to have vegetations on the leads of his new device, but the new pocket showed no evidence of infection at the time when the second device was extracted. Both infections were caused by methicillin-sensitive S. aureus. We believe that the second infection was independent of the first because this patient continued to abuse intravenous heroin and because the second infection occurred at a separate anatomic site.

Two of our patients developed post-operative bleeding. One (#27) was placed on full heparin anticoagulation in the post-operative period because of a mechanical pulmonary valve. Two days after the procedure he developed a hematoma at his surgical site. The intensity of heparin anticoagulation was reduced and suction from his NPWT device was turned off. Blood continued to ooze from the wound, so he was taken to the operating room where bleeding was controlled by electrocautery and placing additional figure-of-eight sutures deep to the muscle layer. A second patient was noted to have a stable 4 × 4 cm pocket hematoma after the procedure. His NPWT system drained about 80 ml of frank blood in the immediate post-operative period. This episode was self-limited and he did not require transfusion or surgical intervention.

Discussion

The treatment of infected wounds poses a problem in surgical management. Primary closure is usually avoided because it can entrap bacteria beneath the skin, delaying clearance of the infection and possibly leading to the formation of an abscess. Because of these concerns the infected wound is usually left open to the air and allowed to heal by secondary intention; the wound eventually heals as granulation tissue slowly grows in from the wound margins and the surface becomes re-epithelialized. Although healing by secondary intention allows efficient clearance of an infection, wound healing can be prolonged, can entail frequent wet-to-dry dressing changes, and can result in a more extensive scar. Another option is to close the wound but to leave a surgical drain in place in order to promote removal of bacteria, edema fluid, and small bits of infected tissue from the wound bed. Placing a drain, however, introduces a foreign body into the wound, raising the possibility that an infected biofilm will form around it and cause a persistent infection. Furthermore, areas of the infected pocket may not be completely accessible to the drain.

In the past decade negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has been introduced as a new treatment modality for infected wounds, and the literature is replete with reports of its efficacy.30 NPWT carries several distinct advantages over the standard therapies described above. Negative pressure can remove bacteria and edema fluid more efficiently than gravity drainage and can promote blood flow into the infected area. Negative pressure can be applied over the entire wound bed, minimizing the possibility that pockets of infection will go untreated. There is also evidence that it promotes angiogenesis, the secretion of growth factors, and cell division in granulation tissue.12–14

Clinical experience using NPWT to treat CIED pocket infections has been limited. In previous reports NPWT was used in atypical cases where the standard therapy of complete device extraction could not be employed, because of either the patient's wishes, technical difficulties, or a perceived high surgical risk. In the first reported case,25 NPWT was employed because a large ulcer had formed around the site where the device had eroded through the skin. After the ulcer was excised the wound could not be primarily closed because the edges could not be approximated. A second report described four elderly patients who either did not undergo complete device extraction or a second system was implanted in an infected field.24 A third report described five cases where the CIED was extracted and the leads were shortened but left in place.23 NPWT was employed for a prolonged period of time (∼34 days) with the expectation that it would allow clearance of the infection. The average length of stay for these patients was 38.6 days, and one of the five patients developed re-infection after 69 days.

Here, we report the routine use of NPWT to treat 28 patients with CIED pocket infections. Our patients represent a typical spectrum of cases where device extraction becomes necessary.31 Almost all of our patients had positive blood or wound cultures, and about two-thirds had staphylococcal infections. About one-third of the infections were peri-procedural and about two-thirds occurred as a result of chronic device erosion through the skin. Most patients had one or more risk factors for device infection. We found that NPWT is safe and effective and does not appear to prolong the length of hospital stay after extraction. All wounds healed completely by delayed primary closure and gave a good cosmetic result. Most importantly, we found that NPWT is associated with a low risk of recurrent infection. Only one of our 28 patients developed a recurrent pocket infection. In this case NPWT was discontinued prematurely when the patient was transferred to a different hospital and the new CIED was inserted at the previously infected site. The presence of a temporary pacemaker does not seem to inhibit clearance of the infection, and we routinely remove it at the time of re-implantation. Although all of our patients were kept in-house during NPWT, the treatment could be continued on an outpatient basis because the dressing changes are infrequent. The suction manifold is battery-powered and portable.

Two of our patients developed post-operative bleeding while on NPWT. Neither required a transfusion, but one required surgical intervention. To avoid bleeding complications, we stress the importance of complete hemostasis at the time of device extraction, before negative pressure is applied. We recommend that full anticoagulation be avoided if possible in patients while NPWT is applied, and that the negative suction pressure be lowered from 125 to 75 mmHg if the patient is to be anticoagulated.

Our results must be interpreted in light of their limitations. We did not directly compare NPWT to another form of wound therapy in a randomized manner, nor did we compare patients who received NPWT to a group of historical controls who did not. Such comparisons would be necessary before one could conclude that NPWT was superior. If the overall incidence of wound complications is low, a greater number of patients than we present here would need to be studied in order to demonstrate a difference.

Conclusion

We conclude that NPWT is a safe and effective treatment for CIED pocket infections that gives a good cosmetic result and has a low incidence of recurrent infection. Controlled prospective randomized trials will be needed to establish whether NPWT results in a lower incidence of re-infection or reduced mortality compared with primary closure, delayed primary closure, or closure by secondary intention.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Europace online.

Conflict of interest: none declared.