-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Antonio Raviele, Franco Giada, Lennart Bergfeldt, Jean Jacques Blanc, Carina Blomstrom-Lundqvist, Lluis Mont, John M. Morgan, M.J. Pekka Raatikainen, Gerhard Steinbeck, Sami Viskin, Document reviewers, Paulus Kirchhof, Frieder Braunschweig, Martin Borggrefe, Meleze Hocini, Paolo Della Bella, Dipen Chandrakant Shah, Management of patients with palpitations: a position paper from the European Heart Rhythm Association, EP Europace, Volume 13, Issue 7, July 2011, Pages 920–934, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eur130

Close - Share Icon Share

Introduction

Aim of the document

Palpitations are among the most common symptoms that prompt patients to consult general practitioners, cardiologists, or emergency healthcare services.1–4 Very often, however, the diagnostic and therapeutic management of this symptom proves to be poorly efficacious and somewhat frustrating for both the patient and the physician. Indeed, in many cases a definitive, or at least probable, diagnosis of the cause of palpitations is not reached and no specific therapy is initiated.5,6 This means that many patients continue to suffer recurrences of their symptoms, which impair their quality of life and mental balance, lead to the potential risk of adverse clinical events, and induce continual recourse to healthcare facilities.

These difficulties stem from the fact that palpitations are generally a transitory symptom. Indeed, at the moment of clinical evaluation, the patient is often asymptomatic and the diagnostic evaluation focuses on the search for pathological conditions that may be responsible for the symptom. This gives rise to some uncertainty in establishing a cause–effect relationship between any anomalies that may be detected and the palpitations themselves. Moreover, as palpitations may be caused by a wide range of different physiological and pathological conditions, clinicians tend to apply a number of instrumental investigations, laboratory tests, and specialist examinations, which are both time-consuming and costly. Comparable, for example, to syncope, such an approach is warranted in selected patients, whereas other patients with palpitations may not require such careful follow-up. The initial clinical assessment should, therefore, include an educated estimation of the likelihood of a relevant underlying arrhythmia in a patient with palpitations (‘gatekeeper' function).

The current management of patients with palpitations is guided chiefly by the clinical experience of the physician. Indeed, the literature lacks specific policy documents or recommendations regarding the most appropriate diagnostic work-up to be adopted in individual patients. The aim of this article is to propose expert advice for diagnostic evaluation in order to guide optimal management of patients with palpitations.

Definition

Palpitations are a symptom defined as awareness of the heartbeat and are described by patients as a disagreeable sensation of pulsation or movement in the chest and/or adjacent areas.7 Implicit in that awareness is a sense of unpleasantness which may be associated with discomfort, alarm, and less commonly pain. As this awareness causes the individual to mentally focus on their heartbeat, the nature of the heartbeat, both in terms of its perceived ‘forcefulness' and its rate, is assimilated into the term. Therefore, the term is used to describe a patient's subjective perception of abnormal cardiac activity in a way that may be associated with a symptomatic cardiac arrhythmia. However, because palpitations are a symptom with a broad range of causes and underlying diseases, it does not have a rigorous and definable clinical correlate.

In normal resting conditions, the activity of the heart is generally not perceived by the individual. However, during or immediately after intense physical activity or emotional stress, it may be quite normal to become aware of one's own heartbeat for brief periods; these sensations are regarded as physiological palpitations, in that they represent the normal or expected response to a certain challenge or activity leading to an increase in the frequency and strength of the contraction of the heart. Outside of such situations, instead, palpitations are perceived as abnormal.5–9

Pathophysiology

Little is known about the events responsible for heartbeat sensation, the afferent sensory pathways that are involved, or the higher-order cognitive processing that filters, modulates, and amplifies these stimuli and brings some to conscious attention.10 Possible sensory receptors are myocardial, pericardial, and peripheral mechanoreceptors, and/or peripheral baroreceptors with their afferent parasympathetic and sympathtic pathways.11,12 Possible brain centres involved in the elaboration of afferent stimuli are the subcortical areas (thalamus, amygdala) and the base of the frontal lobes.

From the pathophysiological standpoint, the mechanisms underlying palpitations are somewhat heterogeneous: contractions of the heart that are too rapid, irregular or particularly slow, as in cardiac arrhythmias including sinus tachycardia secondary to mental disturbance, systemic diseases, or the use of certain medications; very intense contractions and anomalous movements of the heart in the chest, as in the case of some structural heart diseases associated with increased stroke volume; anomalies in the subjective perception of the heartbeat, whereby a normal heart rhythm or minimal irregularities in the cardiac rhythm are felt by the patient and are poorly tolerated, as in the case of some psychosomatic disorders. It is arguable that the pathophysiology of palpitations in these cases is a centrally mediated ‘fright reaction' that initiates a series of responses which include perception of the beating heart.1

It is important to underline the fact that, although cardiac rhythm disorders generally give rise to palpitations (or other related symptoms, such as fatigue, dyspnoea, dizziness, syncope, and angina), in some subjects, for reasons not entirely known but probably linked to some clinical characteristics (long-standing arrhythmias with relatively low maximum ventricular rate, male sex, absence of coronary heart disease, and congestive heart failure) or to the presence of peripheral neuropathy (e.g. diabetic patients), arrhythmias including prognostically relevant disorders such as non-sustained ventricular tachycardias and atrial fibrillation may remain completely asymptomatic.11,13–15 Thus, in such patients, relevant arrhythmias might not be adequately diagnosed and managed.15

Aetiological classification

From the aetiological point of view, the causes of palpitations can be subdivided into five main groups (Table 1): cardiac arrhythmias, structural heart diseases, psychosomatic disorders, systemic diseases, and effects of medical and recreational drugs.3–9 It is not uncommon, however, for the patient to have more than one potential cause or type of palpitation. Electrocardiographic documentation of a rhythm disorder during spontaneous symptoms provides the strongest evidence of causality; whenever this proves possible, therefore, the palpitations are classified as being of arrhythmic origin. By contrast, they are considered to be of non-arrhythmic origin when the underlying heart rhythm exhibits sinus rhythm or sinus tachycardia. Thus, according to this aetiological hierarchy, non-arrhythmic causes of palpitations emerge as definitive diagnoses only in cases in which the symptom–electrocardiogram (ECG) correlation excludes the presence of rhythm disorders.8 When it is not possible to document the cardiac rhythm during palpitations, non-arrhythmic causes are regarded as probable, but not definitive.

| Cardiac arrhythmias |

| Supraventricular/ventricular extrasystoles |

| Supraventricular/ventricular tachycardias |

| Bradyarrhythmias: severe sinus bradycardia, sinus pauses, second- and third-degree atrioventricular block |

| Anomalies in the functioning and/or programming of pacemakers and ICDs |

| Structural heart diseases |

| Mitral valve prolapse |

| Severe mitral regurgitation |

| Severe aortic regurgitation |

| Congenital heart diseases with significant shunt |

| Cardiomegaly and/or heart failure of various aetiologies |

| Hyperthrophic cardiomyopathy |

| Mechanical prosthetic valves |

| Psychosomatic disorders |

| Anxiety, panic attacks |

| Depression, somatization disorders |

| Systemic causes |

| Hyperthyroidism, hypoglycaemia, postmenopausal syndrome, fever, anaemia, pregnancy, hypovolaemia, orthostatic hypotension, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, pheochromocytoma, arteriovenous fistula |

| Effects of medical and recreational drugs |

| Sympathicomimetic agents in pump inhalers, vasodilators, anticholinergics, hydralazine |

| Recent withdrawal of β-blockers |

| Alcohol, cocaine, heroin, amphetamines, caffeine, nicotine, cannabis, synthetic drugs |

| Weight reductions drugs |

| Cardiac arrhythmias |

| Supraventricular/ventricular extrasystoles |

| Supraventricular/ventricular tachycardias |

| Bradyarrhythmias: severe sinus bradycardia, sinus pauses, second- and third-degree atrioventricular block |

| Anomalies in the functioning and/or programming of pacemakers and ICDs |

| Structural heart diseases |

| Mitral valve prolapse |

| Severe mitral regurgitation |

| Severe aortic regurgitation |

| Congenital heart diseases with significant shunt |

| Cardiomegaly and/or heart failure of various aetiologies |

| Hyperthrophic cardiomyopathy |

| Mechanical prosthetic valves |

| Psychosomatic disorders |

| Anxiety, panic attacks |

| Depression, somatization disorders |

| Systemic causes |

| Hyperthyroidism, hypoglycaemia, postmenopausal syndrome, fever, anaemia, pregnancy, hypovolaemia, orthostatic hypotension, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, pheochromocytoma, arteriovenous fistula |

| Effects of medical and recreational drugs |

| Sympathicomimetic agents in pump inhalers, vasodilators, anticholinergics, hydralazine |

| Recent withdrawal of β-blockers |

| Alcohol, cocaine, heroin, amphetamines, caffeine, nicotine, cannabis, synthetic drugs |

| Weight reductions drugs |

| Cardiac arrhythmias |

| Supraventricular/ventricular extrasystoles |

| Supraventricular/ventricular tachycardias |

| Bradyarrhythmias: severe sinus bradycardia, sinus pauses, second- and third-degree atrioventricular block |

| Anomalies in the functioning and/or programming of pacemakers and ICDs |

| Structural heart diseases |

| Mitral valve prolapse |

| Severe mitral regurgitation |

| Severe aortic regurgitation |

| Congenital heart diseases with significant shunt |

| Cardiomegaly and/or heart failure of various aetiologies |

| Hyperthrophic cardiomyopathy |

| Mechanical prosthetic valves |

| Psychosomatic disorders |

| Anxiety, panic attacks |

| Depression, somatization disorders |

| Systemic causes |

| Hyperthyroidism, hypoglycaemia, postmenopausal syndrome, fever, anaemia, pregnancy, hypovolaemia, orthostatic hypotension, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, pheochromocytoma, arteriovenous fistula |

| Effects of medical and recreational drugs |

| Sympathicomimetic agents in pump inhalers, vasodilators, anticholinergics, hydralazine |

| Recent withdrawal of β-blockers |

| Alcohol, cocaine, heroin, amphetamines, caffeine, nicotine, cannabis, synthetic drugs |

| Weight reductions drugs |

| Cardiac arrhythmias |

| Supraventricular/ventricular extrasystoles |

| Supraventricular/ventricular tachycardias |

| Bradyarrhythmias: severe sinus bradycardia, sinus pauses, second- and third-degree atrioventricular block |

| Anomalies in the functioning and/or programming of pacemakers and ICDs |

| Structural heart diseases |

| Mitral valve prolapse |

| Severe mitral regurgitation |

| Severe aortic regurgitation |

| Congenital heart diseases with significant shunt |

| Cardiomegaly and/or heart failure of various aetiologies |

| Hyperthrophic cardiomyopathy |

| Mechanical prosthetic valves |

| Psychosomatic disorders |

| Anxiety, panic attacks |

| Depression, somatization disorders |

| Systemic causes |

| Hyperthyroidism, hypoglycaemia, postmenopausal syndrome, fever, anaemia, pregnancy, hypovolaemia, orthostatic hypotension, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, pheochromocytoma, arteriovenous fistula |

| Effects of medical and recreational drugs |

| Sympathicomimetic agents in pump inhalers, vasodilators, anticholinergics, hydralazine |

| Recent withdrawal of β-blockers |

| Alcohol, cocaine, heroin, amphetamines, caffeine, nicotine, cannabis, synthetic drugs |

| Weight reductions drugs |

Palpitations due to arrhythmias

Any type of tachyarrhythmia, regardless of whether or not there is an underlying structural or arrhythmogenic heart disease, can give rise to palpitations: atrial extrasystole, ventricular extrasystole, tachycardias with regular ventricular activity (sinus tachycardia, atrioventricular node reentrant tachycardia, atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia, atrial flutter, atrial tachycardias), and tachycardias with irregular ventricular activity (atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, or atrial tachycardia with variable atrioventricular conduction, torsades de pointes).16,17 By contrast, bradyarrhythmias are more rarely perceived as palpitations: these arrhythmias comprise sinus pauses and severe sinus bradycardia seen in sick sinus syndrome, sudden onset of high-degree atrioventricular block, or of intermittent left-bundle branch block. Anomalies in the functioning and/or programming of pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) (pacemaker-mediated tachycardia, pectoral or diaphragmatic stimulation, pacemaker syndrome, etc.) may also be responsible for palpitations.

Palpitations due to structural heart disease

Some structural heart diseases can give rise to palpitations in the absence of true rhythm disorders. These include, among others, mitral valve prolapse, severe mitral and aortic regurgitation, congenital heart disease with significant shunt, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and mechanical prosthetic valves.18,19

Palpitations due to psychosomatic disorders

Psychosomatic disorders that are most frequently associated with palpitations include anxiety, panic attacks, depression, and somatization, which can either induce sinus tachycardia or modify the patient's subjective perception of a heartbeat that is otherwise normal or presents minimal irregularities.20–23 If no other potential causes can be identified, the palpitations are considered to be of psychosomatic origin when the patient fulfils the criteria specified in the literature for one or more of the abovementioned psychosomatic disorders. It must be borne in mind, however, that cardiac arrhythmias and psychosomatic disorders are not mutually exclusive.5,24 In addition, the adrenergic hyperactivation connected with intense emotions and anxiety can, in itself, predispose the patient to supraventricular and/or ventricular arrhythmias.25–27 Indeed, in the last few years, some studies investigating the correlation between anxiety syndrome and the appearance of arrhythmias have suggested that anxiety exerts a facilitating effect on arrhythmogenesis28 as well as on the patient's perception of the arrhythmia.29 Finally, in a study conducted on patients with documented supraventricular tachycardia, it was found that two-thirds had previously been wrongly diagnosed as suffering from panic attack disorder, and that the diagnosed ‘psychosomatic disease' could be cured by catheter ablation in most of these patients.30 Thus, even in patients affected by psychosomatic disorders, it is important to carry out a thorough investigation before excluding an organic cause, particularly arrhythmic, of palpitations.

Palpitations due to systemic causes

A sensation of palpitation may stem from sinus tachycardia and/or increased cardiac contractility, both of which may have various causes: fever, anaemia, orthostatic hypotension, hyperthyroidism/thyreotoxicosis, postmenopausal syndrome, pregnancy, hypoglycaemia, hypovolaemia, pheochromocytoma, arteriovenous fistula, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, among others.31–39

Palpitations due to the effects of medical and recreational drugs

In such cases, palpitations may be linked to sinus tachycardia; drugs involved include sympathomimetics, anticholinergics, vasodilators, and hydralazine.40 The sudden suspension of β-blocker therapy may also give rise to sinus tachycardia and palpitations through the induction of a hyperadrenergic state as a result of the ‘rebound' effect. Moreover, palpitations may even occur after the initiation or dose-increase of β-blockers, due to the perception of pulsations caused by increased stroke volume with lower heart rate, or ventricular ectopic beats if sinus overdrive is withdrawn. Likewise, stimulants such as caffeine and nicotine, or the use of illicit drugs (cocaine, heroin, amphetamines, LSD, synthetic drugs, cannabis, etc.) can lead to sympathetic hyperactivation and sinus tachycardia, even in young subjects without heart disease.41,42 Drugs that prolong QT and predispose patients to torsades de pointes and other tachyarrhythmias, such as antidepressive drugs, besides provoking dizziness or syncope, may also induce arrhythmia-related palpitations.43,44 In the absence of other potential causes, palpitations are regarded as secondary to the use of drugs when they are associated temporally to administration of the drug and when they cease on suspension of the drug.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of palpitations is dependent on definitions and diagnostic methods used and varies substantially in different populations. Nevertheless, there is evidence that palpitations are a very frequent symptom in the general population2,9 and, in particular, in patients suffering from hypertension or heart disease. In studies in primary care settings, palpitations account for 16% of the symptoms that prompt patients to visit their general practitioner, and are second only to chest pain as the presenting complaint for specialist cardiologic evaluation.1,3,4 This high prevalence of palpitations emphasizes the need for a structured, ideally evidence-based, step-wise work-up that may allow to distinguish, since the beginning, between patients with benign prognosis and those with poorer prognosis.

With regard to the prevalence of the various causes of palpitations, clinical evidence indicates that a considerable number of subjects with palpitations have normal sinus rhythm or minor rhythm anomalies, such as short bursts of supraventricular extrasystoles or sporadic ventricular extrasystoles. Nevertheless, clinically significant arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation/flutter or paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardias are also a frequent finding.45,46 In a prospective study by Weber and Kapoor47 in 190 patients presenting with a complaint of palpitations at an university medical centre, palpitations were due to arrhythmias in 41% of these patients (16% of whom had atrial fibrillation/flutter, 10% had supraventricular tachycardia, and 2% had ventricular tachycardia), to structural heart disease in 3%, to psychosomatic disorders in 31% (mainly panic and anxiety disorders), to systemic causes in 4%, and to the use of a medication, illicit substances, or stimulants in 6%. According to the case records, the prevalence of anxiety syndrome and panic attacks in patients with palpitations ranges from 15% to 31%.20–22 In the study by Weber and Kapoor,47 male sex, description of an irregular heartbeat, history of heart disease, and event duration >5 min were found to be independent predictors of a cardiac aetiology. No specific cause of palpitations could be identified in 16% of the patients despite a thorough evaluation including the use of loop recorders. Indeed, it is not always possible to establish a definite cause of palpitations; often, only a likely cause can be given, and, in some cases, several possible causes have to be taken into consideration.8,42 In the literature, there are insufficient data about the age and gender distribution of palpitations. In general, however, older patients and men are more likely to have an arrhythmic cause of palpitations and younger patients and women a psychosomatic cause.47–51

Prognosis

The prognostic implications of palpitations are dependent on the underlying aetiology as well as clinical characteristics of the patient. Available data, especially in terms of long-term prognosis, are scarce. Although palpitations are generally associated with low rates of mortality,4,47 they should bring to attention a potential serious condition in patients with structural or arrhythmogenic heart disease or a family history of sudden death. This is also important to keep in mind if the palpitations are associated with symptoms of haemodynamic impairment (dyspnoea, syncope, pre-syncope, dizziness, fatigue, chest pain, neurovegetative symptoms).5 On the one hand, depending on the clinical characteristics of the patient, palpitations due to arrhythmias, in particular of ventricular origin, but also atrial fibrillation, are associated with different prognostic implications.15–17 On the other hand, in patients without relevant heart disease, palpitations (especially if anxiety-related or extrasystolic) generally have a benign prognosis. A retrospective American study that analysed case records obtained from general practitioners found no difference in 5-year mortality and morbidity between patients with palpitations and a group of asymptomatic control subjects.4 Also in the abovementioned study by Weber and Kapoor47 on a general population of patients presenting with palpitations at an university medical centre, despite the high rate of cardiac cause, 1-year mortality was only 1.6%. However, even in patients without severe heart disease, palpitations may be due to significant arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, or ventricular ectopic beats, all of which require adequate investigation and treatment. Moreover, clinical characteristics of the patient, such as age, presence of heart disease, and ECG abnormalities, do not always allow the physician to identify a priori those cases in which palpitations are caused by clinically significant rhythm disorders.8,47,48,52–54 An exception to this is given by changes in the resting ECG that are indicative of primary electrical heart diseases.

In athletes, palpitations are not uncommon. Sudden death, in particular in younger athletes, is rare and mostly associated with underlying structural heart disease or primary arrhythmic disorders, and palpitations may be the initial clinical symptom or an incidental finding possibly leading to the recognition of a previously undiagnosed relevant heart disease.55,56 Moreover, because of potentially life-threatening haemodynamic consequences of even supraventricular arrhythmias, such as rapidly conducted pre-excited atrial fibrillation during exertion, careful cardiac evaluation, in particular of symptomatic competitive as well as recreational athletes, is warranted.57

Although palpitations display a low mortality rate, the recurrence of symptoms is, however, very frequent. In the study by Weber and Kapoor,4777% of patients experienced at least one recurrence of palpitations, and the effect on their quality of life was unfavourable: one-third of patients reported an impairment of their ability to attend to household chores, 19% claimed that their working capacity had diminished, and 12% said that they had taken days off work. These findings are confirmed by a prospective study conducted by Barsky et al.58 on 145 patients with palpitations, who were followed up for 6 months and compared with an asymptomatic control group. These authors observed that patients with palpitations, in spite of having a favourable prognosis in terms of mortality, remained symptomatic and functionally impaired over time and exhibited a high incidence of panic attacks and psychological symptoms.58 Frequent and recurrent palpitations, therefore, can impair the patient's quality of life, giving rise to anxiety and frequent visits to the emergency department.3 In many respects, palpitations seem to behave like a chronic disorder that has a favourable prognosis, but with periodic attacks followed by transitory remission.3,4

Clinical presentation

Duration and frequency of palpitations

With regard to duration, palpitations may be either short-lasting or persistent. In short-lasting forms, the symptom terminates spontaneously within a brief period of time. In persistent forms, the palpitations are ongoing and terminate only after adequate medical treatment. With regard to frequency, palpitations may occur daily, weekly, monthly, or yearly.

Types of palpitations

Patients report a wide range of sensations to describe their symptoms. The most common descriptions, and those most useful in clinical practice in differential diagnoses among the various causes of palpitations, enable palpitations to be classified according to the rate, rhythm, and intensity of heartbeat5–9,59,60: extrasystolic palpitations, tachycardiac palpitations, anxiety-related palpitations, and pulsation palpitations (Table 2). It should, however, be stressed that patients are not always able to describe the characteristics of their symptoms precisely. It may therefore be difficult to identify the type of palpitation accurately, especially in the case of normal-rate palpitations.5,9,61

| Type of palpitation . | Subjective description . | Heartbeat . | Onset and termination . | Trigger situations . | Possible associated symptoms . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrasystolic | ‘Skipping/missing a beat’, ‘sinking of the heart’ | Irregular, interspersed with periods of normal heartbeat | Sudden | Rest | — |

| Tachycardiac | ‘Beating wings’ in the chest | Regular or irregular, markedly accelerated | Sudden | Physical effort, cooling down | Syncope, dyspnoea, fatigue, chest pain |

| Anxiety-related | Anxiety, agitation | Regular, slightly accelerated | Gradual | Stress, Anxiety attacks | Tingling in the hands and face, lump in the throat, atypical chest pain, sighing dyspnoea |

| Pulsation | Heart pounding | Regular, normal frequency | Gradual | Physical effort | Asthenia |

| Type of palpitation . | Subjective description . | Heartbeat . | Onset and termination . | Trigger situations . | Possible associated symptoms . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrasystolic | ‘Skipping/missing a beat’, ‘sinking of the heart’ | Irregular, interspersed with periods of normal heartbeat | Sudden | Rest | — |

| Tachycardiac | ‘Beating wings’ in the chest | Regular or irregular, markedly accelerated | Sudden | Physical effort, cooling down | Syncope, dyspnoea, fatigue, chest pain |

| Anxiety-related | Anxiety, agitation | Regular, slightly accelerated | Gradual | Stress, Anxiety attacks | Tingling in the hands and face, lump in the throat, atypical chest pain, sighing dyspnoea |

| Pulsation | Heart pounding | Regular, normal frequency | Gradual | Physical effort | Asthenia |

| Type of palpitation . | Subjective description . | Heartbeat . | Onset and termination . | Trigger situations . | Possible associated symptoms . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrasystolic | ‘Skipping/missing a beat’, ‘sinking of the heart’ | Irregular, interspersed with periods of normal heartbeat | Sudden | Rest | — |

| Tachycardiac | ‘Beating wings’ in the chest | Regular or irregular, markedly accelerated | Sudden | Physical effort, cooling down | Syncope, dyspnoea, fatigue, chest pain |

| Anxiety-related | Anxiety, agitation | Regular, slightly accelerated | Gradual | Stress, Anxiety attacks | Tingling in the hands and face, lump in the throat, atypical chest pain, sighing dyspnoea |

| Pulsation | Heart pounding | Regular, normal frequency | Gradual | Physical effort | Asthenia |

| Type of palpitation . | Subjective description . | Heartbeat . | Onset and termination . | Trigger situations . | Possible associated symptoms . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrasystolic | ‘Skipping/missing a beat’, ‘sinking of the heart’ | Irregular, interspersed with periods of normal heartbeat | Sudden | Rest | — |

| Tachycardiac | ‘Beating wings’ in the chest | Regular or irregular, markedly accelerated | Sudden | Physical effort, cooling down | Syncope, dyspnoea, fatigue, chest pain |

| Anxiety-related | Anxiety, agitation | Regular, slightly accelerated | Gradual | Stress, Anxiety attacks | Tingling in the hands and face, lump in the throat, atypical chest pain, sighing dyspnoea |

| Pulsation | Heart pounding | Regular, normal frequency | Gradual | Physical effort | Asthenia |

Extrasystolic palpitations, due to ectopic beats, generally produce feelings of ‘missing/skipping a beat' and/or a ‘sinking of the heart' interspersed with periods during which the heart beats normally; patients report that the heart seems to stop and then start again, causing an unpleasant, almost painful, sensation of a blow to the chest. Linked to the presence of atrial or ventricular extrasystolic beats, this type of palpitation is frequently encountered even in young subjects, often in the absence of heart disease, and generally has a benign prognosis. In extrasystolic palpitations, particularly if they are of ventricular origin, the sensation is due to the increased strength of contraction of the post-extrasystolic beat, which accentuates the movement of the heart inside the chest, or to the post-extrasystolic pause, or to the altered activation of the heart. When the extrasystoles are particularly numerous and/or repetitive, it may prove difficult to make a differential diagnosis between extrasystolic and tachycardiac palpitations, especially those due to atrial fibrillation.

In the case of tachycardiac palpitations, the sensation described by the patient is that of a rapid fluctuation like ‘beating wings' in the chest. The heartbeat is generally perceived to be very rapid (sometimes higher than the maximum heart rate estimated on the basis of the patient's age); it may be regular, as in atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia, atrial flutter, or ventricular tachycardia, or irregular or arrhythmic, as in atrial fibrillation or post-atrial fibrillation-ablation atypical atrial flutter (Table 3). These palpitations are generally linked to supraventricular or ventricular tachyarrhythmias, which begin and usually end suddenly (sometimes the termination is gradual due to the increase in sympathetic tone during tachycardia that tends to persist and declines slowly after its interruption), or to sinus tachycardia due to systemic causes or to the use of drugs or illicit substances (in these cases, palpitations begin and end gradually).

| Type of arrhythmia . | Heartbeat . | Trigger situations . | Associated symptoms . | Vagal manoeuvres . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVRT, AVNRT | Sudden onset regular with periods of elevated heart rate | Physical effort, changes in posture | Polyuria, frog sign | Sudden interruption |

| Atrial fibrillation | Irregular with variable heart rate | Physical effort, cooling down, post meal, alcohol intake | Polyuria | Transitory reduction in heart rate |

| Atrial tachycardia and atrial Flutter | Regular (irregular if A-V conduction is variable) with elevated heart rate | Transitory reduction in heart rate | ||

| Ventricular tachycardias | Regular with elevated heart rate | Physical effort | Signs/symptoms of haemodynamic impairment | No effect |

| Type of arrhythmia . | Heartbeat . | Trigger situations . | Associated symptoms . | Vagal manoeuvres . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVRT, AVNRT | Sudden onset regular with periods of elevated heart rate | Physical effort, changes in posture | Polyuria, frog sign | Sudden interruption |

| Atrial fibrillation | Irregular with variable heart rate | Physical effort, cooling down, post meal, alcohol intake | Polyuria | Transitory reduction in heart rate |

| Atrial tachycardia and atrial Flutter | Regular (irregular if A-V conduction is variable) with elevated heart rate | Transitory reduction in heart rate | ||

| Ventricular tachycardias | Regular with elevated heart rate | Physical effort | Signs/symptoms of haemodynamic impairment | No effect |

AVRT, atrio-ventricular reentrant tachycardia; AVNRT, atrio-ventricular node reentrant tachycardia; A-V, atrioventricular.

| Type of arrhythmia . | Heartbeat . | Trigger situations . | Associated symptoms . | Vagal manoeuvres . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVRT, AVNRT | Sudden onset regular with periods of elevated heart rate | Physical effort, changes in posture | Polyuria, frog sign | Sudden interruption |

| Atrial fibrillation | Irregular with variable heart rate | Physical effort, cooling down, post meal, alcohol intake | Polyuria | Transitory reduction in heart rate |

| Atrial tachycardia and atrial Flutter | Regular (irregular if A-V conduction is variable) with elevated heart rate | Transitory reduction in heart rate | ||

| Ventricular tachycardias | Regular with elevated heart rate | Physical effort | Signs/symptoms of haemodynamic impairment | No effect |

| Type of arrhythmia . | Heartbeat . | Trigger situations . | Associated symptoms . | Vagal manoeuvres . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVRT, AVNRT | Sudden onset regular with periods of elevated heart rate | Physical effort, changes in posture | Polyuria, frog sign | Sudden interruption |

| Atrial fibrillation | Irregular with variable heart rate | Physical effort, cooling down, post meal, alcohol intake | Polyuria | Transitory reduction in heart rate |

| Atrial tachycardia and atrial Flutter | Regular (irregular if A-V conduction is variable) with elevated heart rate | Transitory reduction in heart rate | ||

| Ventricular tachycardias | Regular with elevated heart rate | Physical effort | Signs/symptoms of haemodynamic impairment | No effect |

AVRT, atrio-ventricular reentrant tachycardia; AVNRT, atrio-ventricular node reentrant tachycardia; A-V, atrioventricular.

Anxiety-related palpitations are perceived by the patient as a form of anxiety. The heartbeat is slightly elevated, but never higher than the maximum heart rate estimated on the basis of the patient's age. These palpitations, whether paroxysmal or persistent, begin and end gradually, and patients describe numerous other associated unspecific symptoms, such as tingling in the hands and face, a lump in the throat, mental confusion, agitation, atypical chest pains, and sighing dyspnoea, that normally precede the palpitations. Anxiety-related palpitations are due to psychosomatic disorders and usually require exclusion of an arrhythmic cause of the symptoms.

Pulsation palpitations are felt as strong, but regular and not particularly rapid, heartbeats. They tend to be persistent and are generally linked to structural heart diseases, such as aortic regurgitation, or to systemic causes involving a high stroke volume, such as fever and anaemia.

Associated symptoms and circumstances

Certain symptoms and circumstances associated to palpitations are often connected with the various causes of the palpitations and may be very helpful in making differential diagnoses.5–9,59,60 Palpitations arising after sudden changes in posture are frequently due to intolerance to orthostatis or to episodes of atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia. The occurrence of syncope or other symptoms, such as severe fatigue, dyspnoea, or angina, in addition to palpitations, is much more frequent in patients with structural heart disease. However, syncope may also occur at the onset of supraventricular tachycardia in patients with a normal heart, as the result of the triggering of a vasovagal reaction.62,63

Polyuria, which is due to the hypersecretion of natriuretic hormone, is typical of atrial tachyarrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation. By contrast, the sensation of a rapid, regular pulse in the neck (usually associated with the ‘frog sign') raises suspicion of supraventricular tachycardia, particularly atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia.64 It is the result of atria contracting against closed tricuspid and mitral valves.9,65 An atrioventricular mechanical dissociation may also occur in the case of ventricular extrasystoles. In this case, however, only one or few pulses are felt in the neck, and the rhythm is more irregular. In supraventricular tachycardias involving the atrioventricular node, patients often learn to interrupt the episode by themselves by applying vagal stimulation through Valsalva's manoeuvre or carotid sinus massage.

Palpitations that arise in situations of anxiety or during panic attacks are generally due to episodes of more or less rapid sinus tachycardia secondary to the mental disturbance. In some cases, however, the patient may have difficulty in discerning whether the palpitations precede or follow the onset of the anxiety or panic attack, and may therefore be unable to suggest whether the palpitations are the cause or the effect of the psychological distress.

During physical exercise, due to an increase in the sympathetic drive, patients may experience, in addition to the normal sensation of a rapid heart rate elicited by intense effort, palpitations due to various types of arrhythmia, such as right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia, atrioventricular node reentrant tachycardia, and polymorphic catecholaminergic ventricular tachycardia. Finally, episodes of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation may occur in the phase immediately following the cessation of physical effort, during which a sudden reduction in sympathetic tone is accompanied by an increase in vagal tone.

Accuracy of clinical features for the diagnosis of arrhythmias

The utility of the features on history for diagnosing an arrhythmic cause of palpitations has been examined in a recent systematic review.48 The likelihood ratio of each feature is, in general, low and only a few features are really predictive. They include history of cardiac disease, palpitations affected by sleeping, or while the patient is at work. Other features such as underlying history of panic disorder and duration of palpitations less than 5 min appear to be useful for ruling out a clinically significant arrhythmia.47 However, data in this regard come from studies with small sample sizes.

Diagnostic strategy

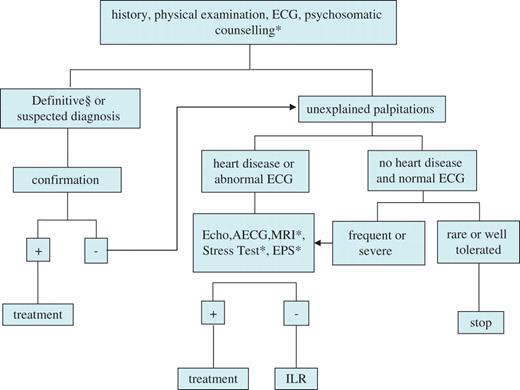

In patients with palpitations the diagnostic strategy should aim at: (i) distinguishing the mechanism of the palpitations; (ii) obtaining an electrocardiographic recording during symptoms; and (iii) evaluating the underlying heart disease. All patients suffering from palpitations should therefore undergo an initial clinical evaluation comprising history, physical examination, and a standard 12-lead ECG (Figure 1). This usually should be performed in a primary care setting.

Diagnostic flow-chart of patients with palpitations. *Indicated only in selected cases; § refers to ECG–symptom correlation available. ECG, electrocardiogram (12-lead); Echo, echocardiography; AECG, ambulatory ECG; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; EPS, electrophysiological study; ILR, implantable loop recorder.

In specific situations, specialist evaluation and certain specific instrumental and laboratory investigations should be considered.59 Stress testing is indicated if the palpitations are associated with physical exertion (e.g. right ventricular outflow tract extrasystoles), in athletes and when coronary heart disease is suspected. The role of echocardiography is of paramount importance to evaluate the presence of structural heart disease. The need to conduct further non-invasive cardiologic investigations (particularly cardiac magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate patients with structural normal heart, palpitations, and frequent ventricular arrhythmias) or invasive investigations (coronary angiography, etc.) will depend on the nature of the heart disease suspected or ascertained. Comparable to exercise-induced syncope, exercise-induced palpitations should raise suspicion for ischaemic, valvular, or other structural heart disease with the corresponding work-up. Whenever a systemic or pharmacological cause of palpitations is suspected, specific laboratory tests should be performed on the basis of the clinical presentation of the symptom and the patient's clinical characteristics (e.g. haemochrome, electrolytes, glycaemia, thyroid function, urinary catecholamines, detection of illicit substances in the blood or urine). If, on the contrary, a psychosomatic cause is suspected, the patient's mental state must be assessed either by means of specific questionnaires or through referral for specialist examination.7,8,20–23

The initial clinical evaluation leads to a definitive or probable diagnosis of the cause of the palpitations in about half of patients, and excludes with reasonable certainty the presence of causes that have an unfavourable prognosis.47 Moreover, a thorough initial clinical evaluation will indicate which specific investigations, if any, are necessary.

If the initial clinical evaluation proves completely unremarkable—which is more frequent in paroxysmal, short-lasting palpitations—the palpitations are deemed to be of unknown origin. In subjects with palpitations of unknown origin who have a low probability of an arrhythmic cause (i.e. patients with gradual onset of palpitations and without significant heart disease and those with anxiety-related or extrasystolic palpitations), further investigations are often not required. The patient should be reassured and a follow-up clinical examination may be scheduled. It should be underlined, however, that, in the absence of electrocardiographic recording during an episode of palpitations, only a presumed or probable diagnosis can be made.30 By contrast, in instances of subjects with palpitations of unknown origin presenting with clinical features suggestive of an arrhythmic cause66 (Table 4), or when palpitations are suspected to be related to atrial fibrillation in individuals with risk factors for thromboembolism,14,67 patients should be referred to an arrhythmia centre, and second-level investigations should be considered; these include ambulatory ECG monitoring and electrophysiological study (EPS) (Figure 1). Finally, second-level investigations should also be carried out in patients with palpitations of unknown origin whose symptoms are frequent or associated with impaired haemodynamic function or impaired quality of life or states of anxiety.9

| Structural heart disease |

| Primary electrical heart disease |

| Abnormal ECG |

| Family history of sudden death |

| Advanced age |

| Tachycardiac palpitations |

| Palpitations associated with haemodynamic impairment |

| Structural heart disease |

| Primary electrical heart disease |

| Abnormal ECG |

| Family history of sudden death |

| Advanced age |

| Tachycardiac palpitations |

| Palpitations associated with haemodynamic impairment |

| Structural heart disease |

| Primary electrical heart disease |

| Abnormal ECG |

| Family history of sudden death |

| Advanced age |

| Tachycardiac palpitations |

| Palpitations associated with haemodynamic impairment |

| Structural heart disease |

| Primary electrical heart disease |

| Abnormal ECG |

| Family history of sudden death |

| Advanced age |

| Tachycardiac palpitations |

| Palpitations associated with haemodynamic impairment |

Initial clinical evaluation

History

It represents a major part of the initial examination as most patients at the time they visit a physician have no palpitations and the diagnosis has to be performed retrospectively.5–9,48 The first step is to establish that symptoms described by the patient match to palpitations and are not confused with chest pain or other manifestations arising in the chest, but that do not correspond to the definition of palpitations described in this article.

When this first step has been achieved several important questions have to be asked, the most important of which are summarized in Table 5. Answers to some of these questions may require inputs from other members of the family or from individuals who have witnessed an episode of palpitations. Description of the type of palpitations (regular or not, rapid or not) could help to determine its underlying mechanism (Table 2). It may be useful to ask the patient to mimic the perceived cardiac rhythm, either vocally or by drumming with the fingers on a table.

| Circumstances prior to the beginning of palpitations |

| Activity (rest, sleeping, during sport or normal exercise, change in posture, after exercise) |

| Position (supine or standing) |

| Predisposing factors (emotional stress, exercise, squatting or bending) |

| Onset of palpitations |

| Abrupt or slowly arising |

| Preceded by other symptoms (chest pain, dyspnoea, vertigo, fatigue, etc.) |

| Episode of palpitations |

| Type of palpitations (regular or not, rapid or not, permanent or not) |

| Associated symptoms (chest pain, syncope or near syncope, sweating, pulmonary oedema, anxiety, nausea, vomiting, etc.) |

| End of the episode |

| Abrupt or slowly decreasing, end or perpetuation of accompanying symptoms, duration, urination |

| Spontaneously or with vagal manoeuvres or drug administration |

| Background |

| Age at the first episode, number of previous episodes, frequency during the last year or month |

| Previous cardiac disease |

| Previous psychosomatic disorders |

| Previous systemic diseases |

| Previous thyroid dysfunction |

| Family history of cardiac disease, tachycardia or sudden cardiac death |

| Medications at the time of palpitations |

| Drug abuse (alcohol and/or others) |

| Electrolytes imbalance |

| Circumstances prior to the beginning of palpitations |

| Activity (rest, sleeping, during sport or normal exercise, change in posture, after exercise) |

| Position (supine or standing) |

| Predisposing factors (emotional stress, exercise, squatting or bending) |

| Onset of palpitations |

| Abrupt or slowly arising |

| Preceded by other symptoms (chest pain, dyspnoea, vertigo, fatigue, etc.) |

| Episode of palpitations |

| Type of palpitations (regular or not, rapid or not, permanent or not) |

| Associated symptoms (chest pain, syncope or near syncope, sweating, pulmonary oedema, anxiety, nausea, vomiting, etc.) |

| End of the episode |

| Abrupt or slowly decreasing, end or perpetuation of accompanying symptoms, duration, urination |

| Spontaneously or with vagal manoeuvres or drug administration |

| Background |

| Age at the first episode, number of previous episodes, frequency during the last year or month |

| Previous cardiac disease |

| Previous psychosomatic disorders |

| Previous systemic diseases |

| Previous thyroid dysfunction |

| Family history of cardiac disease, tachycardia or sudden cardiac death |

| Medications at the time of palpitations |

| Drug abuse (alcohol and/or others) |

| Electrolytes imbalance |

| Circumstances prior to the beginning of palpitations |

| Activity (rest, sleeping, during sport or normal exercise, change in posture, after exercise) |

| Position (supine or standing) |

| Predisposing factors (emotional stress, exercise, squatting or bending) |

| Onset of palpitations |

| Abrupt or slowly arising |

| Preceded by other symptoms (chest pain, dyspnoea, vertigo, fatigue, etc.) |

| Episode of palpitations |

| Type of palpitations (regular or not, rapid or not, permanent or not) |

| Associated symptoms (chest pain, syncope or near syncope, sweating, pulmonary oedema, anxiety, nausea, vomiting, etc.) |

| End of the episode |

| Abrupt or slowly decreasing, end or perpetuation of accompanying symptoms, duration, urination |

| Spontaneously or with vagal manoeuvres or drug administration |

| Background |

| Age at the first episode, number of previous episodes, frequency during the last year or month |

| Previous cardiac disease |

| Previous psychosomatic disorders |

| Previous systemic diseases |

| Previous thyroid dysfunction |

| Family history of cardiac disease, tachycardia or sudden cardiac death |

| Medications at the time of palpitations |

| Drug abuse (alcohol and/or others) |

| Electrolytes imbalance |

| Circumstances prior to the beginning of palpitations |

| Activity (rest, sleeping, during sport or normal exercise, change in posture, after exercise) |

| Position (supine or standing) |

| Predisposing factors (emotional stress, exercise, squatting or bending) |

| Onset of palpitations |

| Abrupt or slowly arising |

| Preceded by other symptoms (chest pain, dyspnoea, vertigo, fatigue, etc.) |

| Episode of palpitations |

| Type of palpitations (regular or not, rapid or not, permanent or not) |

| Associated symptoms (chest pain, syncope or near syncope, sweating, pulmonary oedema, anxiety, nausea, vomiting, etc.) |

| End of the episode |

| Abrupt or slowly decreasing, end or perpetuation of accompanying symptoms, duration, urination |

| Spontaneously or with vagal manoeuvres or drug administration |

| Background |

| Age at the first episode, number of previous episodes, frequency during the last year or month |

| Previous cardiac disease |

| Previous psychosomatic disorders |

| Previous systemic diseases |

| Previous thyroid dysfunction |

| Family history of cardiac disease, tachycardia or sudden cardiac death |

| Medications at the time of palpitations |

| Drug abuse (alcohol and/or others) |

| Electrolytes imbalance |

Circumstances during which palpitations have occurred are generally helpful to evaluate their cause. Some of these circumstances are presented in Table 3. When, after this history-taking, it becomes likely that palpitations are not related to arrhythmia but rather to psychosomatic disorders, before starting more extensive cardiovascular procedures, it is judicious to take the help of a mental health expert.1,22,23,47,58

It is naturally useless to perform this extensive history-taking if the patient has the feeling of palpitation even during the consultation. The first examination in these circumstances is to instantaneously record ECG.

Physical examination

During palpitations

The execution of the physical examination while the patient is still symptomatic is not the most frequent situation. However, when this occurs it is crucial to have some notions about frequency and regularity of heart rhythm by listening to the patient's chest or by palpation of the arterial pulse. The differential diagnosis of various types of tachycardia may be guided by vagal manoeuvres68 such as carotid sinus massage: sudden interruption of the tachycardia is highly suggestive of a tachycardia involving the atrioventricular junction whereas a temporary reduction of the frequency is suggestive of atrial fibrillation, flutter, or atrial tachycardia (Table 3).

When this essential stage has been performed, examination should aim to evaluate the tolerance of a possible heart rhythm disturbance (blood pressure, signs of cardiac failure, and so on), to assess the cardiovascular status (i.e. the presence of structural heart disease), and, in case of a sinus rhythm or sinus tachycardia, to evaluate the presence of systemic diseases potentially responsible for palpitations.

In the absence of palpitations

When the patient is examined in the absence of the culprit symptom, the aim is to find signs of structural heart disease that could explain the occurrence of palpitations (cardiac murmur, hypertension, vascular diseases, signs of heart failure, and so on). It is also important to search for signs of systemic diseases.

Standard electrocardiogram

During palpitations

If the patient is examined during palpitations, 12-lead ECG represents the diagnostic gold standard. Thus, patients should be advised to come as quickly as possible to an emergency department or a physician when an ECG has never been recorded during symptoms. It allows the physician to analyse P and QRS morphologies and the relationship between these two waves, and the frequency and regularity of the heart rhythm, and finally brings an accurate diagnosis on the concordance between palpitations and the presence or absence of arrhythmia. This distinction between arrhythmic or non-arrhythmic palpitation is of paramount importance for the future evaluation.1,5–9,47 Furthermore, precise analysis of ECG during arrhythmia either provides the mechanism or gives important data that lead to this diagnosis. It should be stressed, however, that P waves during rapid tachycardia are not always visible, making the diagnosis difficult. Vagal manoeuvres and pharmacological tests, such as intravenous adenosine or ajmaline, performed during ECG recording are of major interest as they can unmask the atrial activity or interrupt suddenly the tachycardia, resulting in the diagnosis of the type of arrhythmia.16,68 Alternatively, the possibility of taking a transoesophageal ECG during tachycardia must be considered.

In the absence of palpitations

Even when the ECG is recorded in the absence of palpitations it provides important data that can suggest the arrhythmic origin of palpitations (Tables 6 and 7). In some instances, for example in case of evident pre-excitation when the patient reports rapid regular palpitations, the diagnosis is formal even if tachycardia has never been recorded.

Electrocardiographic features recorded on standard electrocardiogram in absence of palpitations and suggestive of palpitations of arrhythmic origin

| Ventricular pre-excitation |

| Atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| P-wave abnormalities, supraventricular premature beats, sinus bradycardia |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy |

| Ventricular tachycardia |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| Frequent ventricular premature beats |

| Ventricular tachycardia |

| Q wave, signs of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, Brugada syndrome or early repolarization syndrome |

| Ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation |

| Long or short QT |

| Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia |

| A-V block, tri- or bifascicular block |

| Torsades de pointes |

| Paroxysmal A-V block |

| Ventricular pre-excitation |

| Atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| P-wave abnormalities, supraventricular premature beats, sinus bradycardia |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy |

| Ventricular tachycardia |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| Frequent ventricular premature beats |

| Ventricular tachycardia |

| Q wave, signs of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, Brugada syndrome or early repolarization syndrome |

| Ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation |

| Long or short QT |

| Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia |

| A-V block, tri- or bifascicular block |

| Torsades de pointes |

| Paroxysmal A-V block |

Electrocardiographic features recorded on standard electrocardiogram in absence of palpitations and suggestive of palpitations of arrhythmic origin

| Ventricular pre-excitation |

| Atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| P-wave abnormalities, supraventricular premature beats, sinus bradycardia |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy |

| Ventricular tachycardia |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| Frequent ventricular premature beats |

| Ventricular tachycardia |

| Q wave, signs of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, Brugada syndrome or early repolarization syndrome |

| Ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation |

| Long or short QT |

| Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia |

| A-V block, tri- or bifascicular block |

| Torsades de pointes |

| Paroxysmal A-V block |

| Ventricular pre-excitation |

| Atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| P-wave abnormalities, supraventricular premature beats, sinus bradycardia |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy |

| Ventricular tachycardia |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| Frequent ventricular premature beats |

| Ventricular tachycardia |

| Q wave, signs of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, Brugada syndrome or early repolarization syndrome |

| Ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation |

| Long or short QT |

| Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia |

| A-V block, tri- or bifascicular block |

| Torsades de pointes |

| Paroxysmal A-V block |

List of eletrocardiographic signs indicative of primary electrical heart diseases

| ECG signs . | Suspected disease . |

|---|---|

| Corrected QT interval >0.46 s | Long QT syndrome |

| Corrected QT interval <0.32 s | Short QT syndrome |

| Right bundle branch block with coved type/saddle type ST segment elevation in the right precordial ECG leads (V1–V3) either spontaneous or provoked by flecainide or ajmaline | Brugada syndrome |

| ε-wave and/or T-wave inversion with QRS duration >110 ms in the right precordial ECG leads (V1–V3); ventricular ectopic beats with left bundle branch block and right-axis deviation morphology | Arrythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy |

| High voltage in the precordial leads, Q wave, ST changes | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| ECG signs . | Suspected disease . |

|---|---|

| Corrected QT interval >0.46 s | Long QT syndrome |

| Corrected QT interval <0.32 s | Short QT syndrome |

| Right bundle branch block with coved type/saddle type ST segment elevation in the right precordial ECG leads (V1–V3) either spontaneous or provoked by flecainide or ajmaline | Brugada syndrome |

| ε-wave and/or T-wave inversion with QRS duration >110 ms in the right precordial ECG leads (V1–V3); ventricular ectopic beats with left bundle branch block and right-axis deviation morphology | Arrythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy |

| High voltage in the precordial leads, Q wave, ST changes | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

List of eletrocardiographic signs indicative of primary electrical heart diseases

| ECG signs . | Suspected disease . |

|---|---|

| Corrected QT interval >0.46 s | Long QT syndrome |

| Corrected QT interval <0.32 s | Short QT syndrome |

| Right bundle branch block with coved type/saddle type ST segment elevation in the right precordial ECG leads (V1–V3) either spontaneous or provoked by flecainide or ajmaline | Brugada syndrome |

| ε-wave and/or T-wave inversion with QRS duration >110 ms in the right precordial ECG leads (V1–V3); ventricular ectopic beats with left bundle branch block and right-axis deviation morphology | Arrythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy |

| High voltage in the precordial leads, Q wave, ST changes | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| ECG signs . | Suspected disease . |

|---|---|

| Corrected QT interval >0.46 s | Long QT syndrome |

| Corrected QT interval <0.32 s | Short QT syndrome |

| Right bundle branch block with coved type/saddle type ST segment elevation in the right precordial ECG leads (V1–V3) either spontaneous or provoked by flecainide or ajmaline | Brugada syndrome |

| ε-wave and/or T-wave inversion with QRS duration >110 ms in the right precordial ECG leads (V1–V3); ventricular ectopic beats with left bundle branch block and right-axis deviation morphology | Arrythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy |

| High voltage in the precordial leads, Q wave, ST changes | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

Ambulatory electrocardiogram monitoring

Ambulatory ECG monitoring serves to document the cardiac rhythm during an episode of palpitations if this cannot be done by means of standard ECG, as in the case of short-lasting symptoms. Indeed, ambulatory ECG monitoring utilizes electrocardiographic recorders that are able to monitor the patient's cardiac rhythm for long periods of time or that can be activated by the patient when symptoms occur.69,70

The devices currently used for ambulatory ECG monitoring can be subdivided into two main categories: external and implantable. External devices comprise Holter recorders, hospital telemetry (reserved for hospitalized patients at high risk of malignant arrhythmias), event recorders, external loop recorders, and, very recently, mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry. Implantable devices comprise pacemakers and ICDs equipped with diagnostic features (used exclusively in patients requiring such devices for therapeutic purposes) and implantable loop recorders (ILRs).

Event recorders or handheld patient-operated ECG systems have been shown to improve the diagnosis of transient ECG changes in patients with palpitations.71,72 These devices are reasonably priced and easy to use. The external and implantable loop recorders, mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry, and pacemakers and ICDs can detect asymptomatic clinically significant arrhythmias automatically (i.e. with no activation by the patient) and provide a significantly higher yield than standard patient-activated loop recorders in patients with infrequent palpitations.49,73–79 Another major benefit of the latest diagnostic systems is that many of them not only allow automatic detection of the arrhythmias but also allow immediate wireless transmission of pertinent ECG data to a central monitoring station via a mobile telephone line or the Internet. The alarms incorporated into the network providing telemetric data to specialists improve the efficiency of patient management, since the physicians can check their patient's data remotely with no delay. This permits greater emphasis on documentation and characterization of spontaneous arrhythmic episodes, and it is expected to allow prompt reaction to clinical events as well as to act as a potential for reduced resource use.80 Moreover, the ability to detect the onset of the episode provides valuable information on the mechanism of the arrhythmias. The main technical characteristics of the different ambulatory ECG monitoring systems are summarized in Table 8.

Technical characteristics of the different ambulatory electrocardiogram monitoring devices

| Device . | Characteristics . |

|---|---|

| Holter monitoring | Utilizes external recorders connected to the patient by means of skin electrodes; these recorders are able to perform continuous beat-to-beat electrocardiographic monitoring via several leads (up to 12 in the latest models). |

| Event recorders | Small, easy-to-use, portable devices that are applied to the patient's skin whenever symptoms are experienced. They provide prospective one-lead electrocardiographic recording for a few seconds. |

| External loop recorders | Connected continuously to the patient by means of skin electrodes and equipped with a memory loop, these devices provide one to three-lead electrocardiographic recording for a few minutes before and after activation by the patient when symptoms arise. The latest devices are also able to self-activate automatically when arrhythmic events occur. |

| Mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry | Made up of an external loop recorder connected to the patient by means of skin electrodes, and of a portable receiver that is able to transmit an electrocardiographic trace to a remote operating centre or to a dedicated website via the telephone. In this way, the patient's rhythm can be monitored in real time. |

| Implantable loop recorders | Similar in size to a pacemaker, these devices are implanted beneath the skin through a small incision of about 2 cm in the left precordial region. They are equipped with a memory loop and, once activated by the patient through an external activator at the moment when the symptoms arise, record one-lead electrocardiographic trace for several minutes before and after the event. They are also able to record any arrhythmic event automatically (i.e. with no intervention by the patient). In general, monitoring lasts either until a diagnosis is reached or until the battery runs down. On completion of monitoring, the device is removed from the patient. |

| Pacemakers/ICDs | Provided by an internal memory, they are able to detect and store an atrial and ventricular IEGM separately (dual chamber devices), and to record any arrhythmic events automatically. Some models may also be activated manually by the patients when palpitations occur. |

| Device . | Characteristics . |

|---|---|

| Holter monitoring | Utilizes external recorders connected to the patient by means of skin electrodes; these recorders are able to perform continuous beat-to-beat electrocardiographic monitoring via several leads (up to 12 in the latest models). |

| Event recorders | Small, easy-to-use, portable devices that are applied to the patient's skin whenever symptoms are experienced. They provide prospective one-lead electrocardiographic recording for a few seconds. |

| External loop recorders | Connected continuously to the patient by means of skin electrodes and equipped with a memory loop, these devices provide one to three-lead electrocardiographic recording for a few minutes before and after activation by the patient when symptoms arise. The latest devices are also able to self-activate automatically when arrhythmic events occur. |

| Mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry | Made up of an external loop recorder connected to the patient by means of skin electrodes, and of a portable receiver that is able to transmit an electrocardiographic trace to a remote operating centre or to a dedicated website via the telephone. In this way, the patient's rhythm can be monitored in real time. |

| Implantable loop recorders | Similar in size to a pacemaker, these devices are implanted beneath the skin through a small incision of about 2 cm in the left precordial region. They are equipped with a memory loop and, once activated by the patient through an external activator at the moment when the symptoms arise, record one-lead electrocardiographic trace for several minutes before and after the event. They are also able to record any arrhythmic event automatically (i.e. with no intervention by the patient). In general, monitoring lasts either until a diagnosis is reached or until the battery runs down. On completion of monitoring, the device is removed from the patient. |

| Pacemakers/ICDs | Provided by an internal memory, they are able to detect and store an atrial and ventricular IEGM separately (dual chamber devices), and to record any arrhythmic events automatically. Some models may also be activated manually by the patients when palpitations occur. |

IEGM, intracardiac electrogram.

Technical characteristics of the different ambulatory electrocardiogram monitoring devices

| Device . | Characteristics . |

|---|---|

| Holter monitoring | Utilizes external recorders connected to the patient by means of skin electrodes; these recorders are able to perform continuous beat-to-beat electrocardiographic monitoring via several leads (up to 12 in the latest models). |

| Event recorders | Small, easy-to-use, portable devices that are applied to the patient's skin whenever symptoms are experienced. They provide prospective one-lead electrocardiographic recording for a few seconds. |

| External loop recorders | Connected continuously to the patient by means of skin electrodes and equipped with a memory loop, these devices provide one to three-lead electrocardiographic recording for a few minutes before and after activation by the patient when symptoms arise. The latest devices are also able to self-activate automatically when arrhythmic events occur. |

| Mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry | Made up of an external loop recorder connected to the patient by means of skin electrodes, and of a portable receiver that is able to transmit an electrocardiographic trace to a remote operating centre or to a dedicated website via the telephone. In this way, the patient's rhythm can be monitored in real time. |

| Implantable loop recorders | Similar in size to a pacemaker, these devices are implanted beneath the skin through a small incision of about 2 cm in the left precordial region. They are equipped with a memory loop and, once activated by the patient through an external activator at the moment when the symptoms arise, record one-lead electrocardiographic trace for several minutes before and after the event. They are also able to record any arrhythmic event automatically (i.e. with no intervention by the patient). In general, monitoring lasts either until a diagnosis is reached or until the battery runs down. On completion of monitoring, the device is removed from the patient. |

| Pacemakers/ICDs | Provided by an internal memory, they are able to detect and store an atrial and ventricular IEGM separately (dual chamber devices), and to record any arrhythmic events automatically. Some models may also be activated manually by the patients when palpitations occur. |

| Device . | Characteristics . |

|---|---|

| Holter monitoring | Utilizes external recorders connected to the patient by means of skin electrodes; these recorders are able to perform continuous beat-to-beat electrocardiographic monitoring via several leads (up to 12 in the latest models). |

| Event recorders | Small, easy-to-use, portable devices that are applied to the patient's skin whenever symptoms are experienced. They provide prospective one-lead electrocardiographic recording for a few seconds. |

| External loop recorders | Connected continuously to the patient by means of skin electrodes and equipped with a memory loop, these devices provide one to three-lead electrocardiographic recording for a few minutes before and after activation by the patient when symptoms arise. The latest devices are also able to self-activate automatically when arrhythmic events occur. |

| Mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry | Made up of an external loop recorder connected to the patient by means of skin electrodes, and of a portable receiver that is able to transmit an electrocardiographic trace to a remote operating centre or to a dedicated website via the telephone. In this way, the patient's rhythm can be monitored in real time. |

| Implantable loop recorders | Similar in size to a pacemaker, these devices are implanted beneath the skin through a small incision of about 2 cm in the left precordial region. They are equipped with a memory loop and, once activated by the patient through an external activator at the moment when the symptoms arise, record one-lead electrocardiographic trace for several minutes before and after the event. They are also able to record any arrhythmic event automatically (i.e. with no intervention by the patient). In general, monitoring lasts either until a diagnosis is reached or until the battery runs down. On completion of monitoring, the device is removed from the patient. |

| Pacemakers/ICDs | Provided by an internal memory, they are able to detect and store an atrial and ventricular IEGM separately (dual chamber devices), and to record any arrhythmic events automatically. Some models may also be activated manually by the patients when palpitations occur. |

IEGM, intracardiac electrogram.

Diagnostic value

Ambulatory ECG monitoring is regarded as diagnostic only when it is possible to establish a correlation between palpitations and an electrocardiographic recording.69,70 In patients who do not develop symptoms during monitoring, therefore, this examination is often non-contributory. In some patients without palpitations on monitoring, the presence of clinically significant arrhythmias that are asymptomatic (i.e. not associated with palpitations) may suggest a probable diagnosis and/or guide the decision to undertake further investigations.15,59 The specificity of ambulatory ECG monitoring, at least in formulating a diagnosis of arrhythmic palpitations or non-arrhythmic palpitations, is optimal, whereas the sensitivity is extremely variable and depends on the following factors: the monitoring techniques used, the duration of monitoring, patient compliance, and, most importantly, the frequency of the attacks.

In patients with palpitations of unknown origin, Holter monitoring has displayed a rather low sensitivity value (33–35%).81 In a meta-analysis of seven studies conducted on patients with syncope and/or palpitations of unknown origin, Holter monitoring has been seen to have a sensitivity value of only 22%.82 By contrast, in patients in whom the symptoms are quite frequent (i.e. daily or weekly), external loop recorders and event recorders have shown both a higher diagnostic value (66–83%) and a better cost/effectiveness ratio than Holter devices.71,83 Finally, in patients with symptoms of possible arrhythmic origin, mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry has been seen to exhibit a higher diagnostic value than the other external devices.71,84,85

ILRs have been successfully used to study syncope, in which they have shown a better cost/effectiveness ratio than the conventional tests,86,87 and they can be useful in the study of palpitations of unknown origin.69,88,89 Indeed, the RUP study (recurrent unexplained palpitations study) recently demonstrated the superiority of ILR over the conventional diagnostic strategy of Holter and event recorder monitoring and EPS in the evaluation of a relatively small cohort of patients with infrequent palpitations (i.e. monthly frequency) reporting both a higher diagnostic value (73% vs. 21%) and a better cost/effectiveness ratio.52 In patients implanted with pacemakers or ICDs, useful information on the origin of palpitations can be obtained by interrogating the memory of the device.90

Although many patients with palpitations of unknown origin who undergo ambulatory ECG monitoring prove to have rhythm disorders that are generally benign, such as atrial or ventricular premature beats, or episodes of sinus rhythm and sinus tachycardia, a substantial percentage (6–35%) of the arrhythmias diagnosed prove to be clinically significant, such as supraventricular tachycardias and atrial fibrillation.5 Ventricular tachycardia is much less common and is typical of patients with structural or arrhythmogenic heart diseases. Finally, a small percentage of patients with palpitations of unknown origin have major bradyarrhythmic disorders, such as severe sinus bradycardia and paroxysmal advanced atrioventricular block.52,71

Limitations

Ambulatory ECG monitoring has some important limitations. Indeed, it is not always possible to formulate a precise diagnosis of the type of arrhythmia recorded, especially when single-lead ECG devices are used. For example, it may be difficult to make a correct differential diagnosis between a supraventricular tachycardia with aberrant conduction and a ventricular tachycardia. Moreover, ambulatory ECG monitoring is unable to distinguish with certainty between bradyarrhythmias due to a reflex mechanism and those caused by a disorder of the cardiac conduction system, a distinction that has prognostic and therapeutic implications. Finally, ambulatory ECG monitoring requires the patient to experience a recurrence of symptoms. This delays the diagnosis and, should the palpitations be due to malignant arrhythmias, exposes the patient to the potential risk of adverse events. The main advantages and limitations of the different ambulatory ECG monitoring systems are summarized in Table 9.

Advantages, limitations, and indications of the different ambulatory electrocardiogram monitoring devices

| . | Holter monitoring . | Event recorders . | External loop recorders/MCOT . | Implantable loop recorders . | Pacemakers/ICDs . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Low cost; possibility to record asymptomatic arrhythmias | Low cost; easy to use | Retrospective and prospective ECG records; possibility to record asymptomatic arrhythmias automatically | Retrospective and prospective ECG records; quite good ECG records; monitoring capability up to 36 months; possibility to record asymptomatic arrhythmias automatically | Better discrimination between ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias, due to dual chamber IEGM recordings; better definition of arrhythmic burden; monitoring duration for many years (corresponding to the expected life of the device); possibility to record asymptomatic arrhythmias automatically |

| Limitations | Monitoring limited to 24 h to 7 days; size may prevent activities that may trigger the arrhythmias; patients often fail to complete adequately the clinical diary upon which the correlation between symptoms and the arrhythmias recorded is based | Monitoring cannot be carried out for more than 3–4 weeks; very brief arrhythmias are not recorded; arrhythmic triggers are not revealed; poor ECG records | Monitoring cannot be carried out for more than 3–4 weeks; continual maintenance is required; devices are uncomfortable; quite poor ECG records | Invasiveness; risk of local complications at the implantation site: higher cost; limited memory and specificity | Invasiveness; risk of early and late local and systemic complications; high costs |