-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Klaus K. Witte, Christopher B. Pepper, J. Campbell Cowan, John D. Thomson, Kate M. English, Michael E. Blackburn, Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in adult patients with tetralogy of Fallot, EP Europace, Volume 10, Issue 8, August 2008, Pages 926–930, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eun108

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Adults with repaired tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) are at risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD). ESC and AHA guidelines suggest the use of implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) to protect from this. Few data are available on the benefits of these devices in this population, and there are no randomized studies.

We analysed outcomes with respect to death, ICD therapy delivery, and complications for 20 patients with repaired TOF and 39 dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) patients followed up at a UK teaching hospital. All TOF patients had clinical ventricular tachycardia (VT), electrophysiological study-inducible VT, or previous arrest due to tachyarrhythmia and received dual-chamber devices with individualized atrial detection algorithms. Tetralogy of Fallot patients were younger than DCM patients, but follow-up duration was not different between the groups. Tetralogy of Fallot patients were more likely to have experienced oversensing (45 vs. 13%; P < 0.02), inappropriate anti-tachycardia pacing delivery (20 vs. 2%; P < 0.05), and inappropriate cardioversion (25 vs. 4%; P = 0.06) than DCM patients and less likely to receive appropriate therapies than DCM patients. The death rate in TOF patients was significantly lower than that in DCM patients (5 vs. 21%; P < 0.05).

Tetralogy of Fallot patients have a higher risk of inappropriate therapies and other complications yet a lower incidence of appropriate therapies from their ICD than DCM patients. Further research into identification of factors predicting SCD in TOF and the benefits of ICD implantation is essential given the potential complications of ICD implantation in young congenital heart disease patients.

Introduction

Advances in the surgical treatment of patients born with congenital heart defects have transformed the prognosis of conditions previously fatal in infancy or childhood. However, annual mortality rate in these patients does not return to normal. The most frequent modes of death include heart failure and sudden cardiac death (SCD) because of arrhythmia. In patients with tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), cardiac dysrhythmia leading to sudden death is thought to account for 30% of late mortality. 1 An SCD rate at late follow-up of between 1.2 and 1.8% per year 2–7 (increasing to 6% per year after 30 years of follow-up 2 , 8 ) is 25–100 times higher than that of an age-matched population. 2 , 3 , 9 Patients with poor exercise capacity, severe symptoms of breathlessness, cardiac enlargement, poor haemodynamics, and symptomatic dysrhythmias are thought to be at higher risk of SCD. 10 Inducible ventricular tachycardia (VT) at electrophysiological study (EPS) has recently been added to this list. 11 However, these features have low specificity and in the absence of sufficiently large randomized controlled trials in congenital heart disease (CHD) populations, registries remain the only available data helping to identify those patients with the most to gain from measures to prevent SCD such as implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) therapy. Guidelines drawn up by the American College of Cardiology, the European Society of Cardiology, and the American Heart Association 12 suggest the use of ICDs in patients with CHD who are survivors of cardiac arrest, those with spontaneous VT not successfully ablated, and those with inducible VT with unexplained syncope and impaired right or left ventricular function. In the UK, NICE guidelines are even broader, suggesting the ‘routine consideration’ of ICD for patients with repaired TOF. 13 Application of these guidelines verbatim would lead to many more patients with repaired TOF having ICDs implanted. However, the absolute benefits of ICD therapy in this group remain unclear and associated morbidity scarcely reported.

Aims

The aim of the current study was to examine the outcomes following ICD implantation in patients with repaired TOF. We chose to compare this group with a group of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) because the evidence base for indications for ICD therapy in DCM is most closely allied with the accepted indications for ICD therapy in patients with CHD.

Methods

Patients

All patients with TOF or DCM with ICDs implanted between 1 December 1996 and 1 December 2006 at a single centre providing supra-regional congenital cardiology services and regional electrophysiological services were included in the study. Case notes were retrieved and reviewed to identify indication, medical therapy, complications, and outcomes. Each therapy delivered was adjudicated by a physician experienced in device therapy. Therapies were classed as anti-tachycardia pacing (ATP) or shock and described as ‘appropriate’ if delivered for VT or ‘inappropriate’ if delivered for an atrial dysrhythmia. Events and mortality were censored at the date of last follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Variables were analysed using a commercially available statistics programme (Statview v5, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Continuous data are presented as means ± 1SD in text and tables, and the groups were compared using Student's t -test. Categorical data were analysed using χ 2 tests. We constructed the Kaplan–Meier curves for the two groups for time to first inappropriate therapy, time to any therapy, and death. A P -value of less than 0.05 was taken as significant.

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patient groups. All patients with TOF received dual-chamber devices. Dilated cardiomyopathy patients had dual chamber ( n = 19), single-chamber ( n = 15), or biventricular ICD ( n = 5) devices. All devices were implanted in the pre-pectoral position. Patients with TOF were younger than those with DCM. Significant (more than mild) right ventricular (RV) dilatation or dysfunction was seen in the majority of the TOF patients, whereas left ventricular function was generally well preserved. Patients with DCM were more likely to have had a previous cardiac arrest. More TOF patients had undergone EPS than DCM patients, and only one DCM patient had had an attempted VT ablation procedure. Electrophysiological study in TOF was performed in order to establish the origin of palpitations, attempt VT ablation, or, additionally, in five cases to ablate supra-ventricular dysrhythmias. All TOF patients were symptomatic with palpitations and had documented VT, either on Holter monitor or EPS and most had been in hospital at least once with ventricular dysrhythmia in the 12 months preceding ICD implantation.

| . | TOF ( n = 25) . | DCM ( n = 39) . | P -value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) (SD) | 24 (7) | 54 (12) | <0.0001 |

| Mean age at repair (years) | 3 (2) | – | |

| β-blockers/amiodarone ( n ) | 17/8 (68/32%) | 20/19 (50/48%) | |

| Primary/secondary ( n ) | 7/18 | 9/30 | |

| Significant RV dilatation/dysfunction ( n ) | 18/17 (72/68%) | 4/3 (10/7%) | Both <0.01 |

| Significant pulmonary incompetence ( n ) | 16 (64%) | 0 | |

| Previous VT ablation ( n ) | 4 (16%) | 1 (2%) | <0.02 |

| Significant LV dysfunction ( n ) | 3 (%) | 37 (95%) | <0.02 |

| Symptoms ( n ) | 25 (100%) | 19 (49%) | <0.02 |

| EPS performed ( n ) | 17 (68%) | 7 (20%) | <0.02 |

| Hospitalized up to 1 year prior to ICD ( n ) | 23 (95%) | 25 (64%) | <0.02 |

| . | TOF ( n = 25) . | DCM ( n = 39) . | P -value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) (SD) | 24 (7) | 54 (12) | <0.0001 |

| Mean age at repair (years) | 3 (2) | – | |

| β-blockers/amiodarone ( n ) | 17/8 (68/32%) | 20/19 (50/48%) | |

| Primary/secondary ( n ) | 7/18 | 9/30 | |

| Significant RV dilatation/dysfunction ( n ) | 18/17 (72/68%) | 4/3 (10/7%) | Both <0.01 |

| Significant pulmonary incompetence ( n ) | 16 (64%) | 0 | |

| Previous VT ablation ( n ) | 4 (16%) | 1 (2%) | <0.02 |

| Significant LV dysfunction ( n ) | 3 (%) | 37 (95%) | <0.02 |

| Symptoms ( n ) | 25 (100%) | 19 (49%) | <0.02 |

| EPS performed ( n ) | 17 (68%) | 7 (20%) | <0.02 |

| Hospitalized up to 1 year prior to ICD ( n ) | 23 (95%) | 25 (64%) | <0.02 |

RV, right ventricular; VT, ventricular tachycardia; LV, left ventricular; EPS, electrophysiological study; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy.

| . | TOF ( n = 25) . | DCM ( n = 39) . | P -value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) (SD) | 24 (7) | 54 (12) | <0.0001 |

| Mean age at repair (years) | 3 (2) | – | |

| β-blockers/amiodarone ( n ) | 17/8 (68/32%) | 20/19 (50/48%) | |

| Primary/secondary ( n ) | 7/18 | 9/30 | |

| Significant RV dilatation/dysfunction ( n ) | 18/17 (72/68%) | 4/3 (10/7%) | Both <0.01 |

| Significant pulmonary incompetence ( n ) | 16 (64%) | 0 | |

| Previous VT ablation ( n ) | 4 (16%) | 1 (2%) | <0.02 |

| Significant LV dysfunction ( n ) | 3 (%) | 37 (95%) | <0.02 |

| Symptoms ( n ) | 25 (100%) | 19 (49%) | <0.02 |

| EPS performed ( n ) | 17 (68%) | 7 (20%) | <0.02 |

| Hospitalized up to 1 year prior to ICD ( n ) | 23 (95%) | 25 (64%) | <0.02 |

| . | TOF ( n = 25) . | DCM ( n = 39) . | P -value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) (SD) | 24 (7) | 54 (12) | <0.0001 |

| Mean age at repair (years) | 3 (2) | – | |

| β-blockers/amiodarone ( n ) | 17/8 (68/32%) | 20/19 (50/48%) | |

| Primary/secondary ( n ) | 7/18 | 9/30 | |

| Significant RV dilatation/dysfunction ( n ) | 18/17 (72/68%) | 4/3 (10/7%) | Both <0.01 |

| Significant pulmonary incompetence ( n ) | 16 (64%) | 0 | |

| Previous VT ablation ( n ) | 4 (16%) | 1 (2%) | <0.02 |

| Significant LV dysfunction ( n ) | 3 (%) | 37 (95%) | <0.02 |

| Symptoms ( n ) | 25 (100%) | 19 (49%) | <0.02 |

| EPS performed ( n ) | 17 (68%) | 7 (20%) | <0.02 |

| Hospitalized up to 1 year prior to ICD ( n ) | 23 (95%) | 25 (64%) | <0.02 |

RV, right ventricular; VT, ventricular tachycardia; LV, left ventricular; EPS, electrophysiological study; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy.

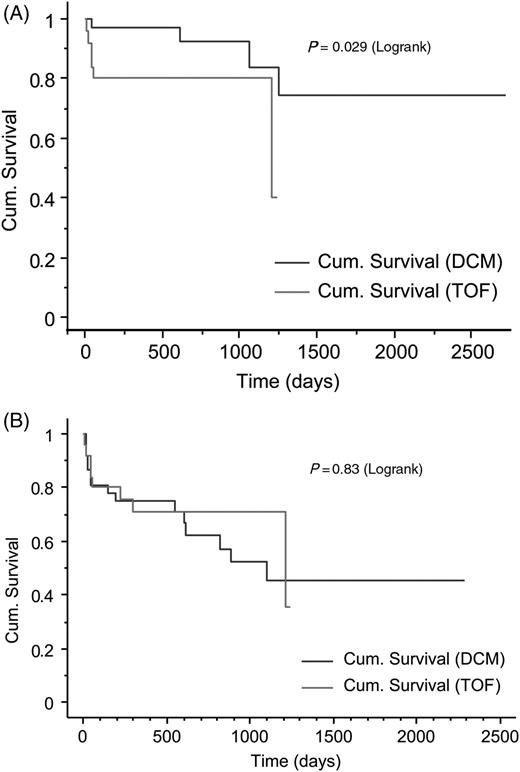

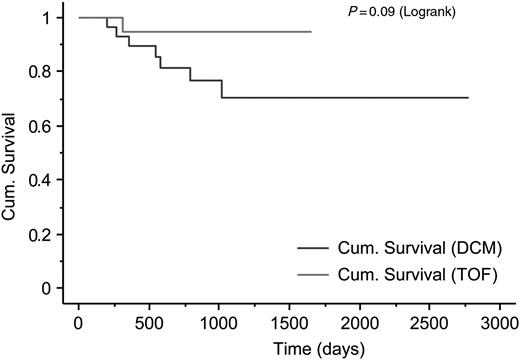

Patient outcomes are shown in Table 2 . Tetralogy of Fallot patients had a higher rate of inappropriate discharges, mostly for misidentified supra-ventricular tachycardias (SVTs), and a lower rate of appropriate discharges, when compared with patients with DCM. Tetralogy of Fallot patients had a slightly higher rate of appropriate ATP therapies than patients with DCM. Only one patient (in the DCM group) had both appropriate ATP and cardioversion. The Kaplan–Meier analysis confirms a higher rate of inappropriate therapy in TOF patients than DCM ( Figure 1 A ), yet no difference between TOF patients and those with DCM for days alive without any therapy ( Figure 1 B ). This is accounted for by a trend towards fewer days alive prior to appropriate therapy for DCM patients. Overall survival in our populations seems to be lower in patients with DCM ( Figure 2 ).

The Kaplan–Meier cumulative survival plot for days alive to ( A ) first inappropriate therapy and ( B ) any therapy.

The Kaplan–Meier cumulative survival plot for patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and tetralogy of Fallot with automatic implantable defibrillators.

| . | TOF ( n = 25) . | DCM ( n = 39) . | P -value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean follow-up (days) (SD) | 695 (493) | 841 (570) | ns |

| Appropriate ATP ( n ) | 4 (20%) | 5 (13%) | ns |

| Appropriate cardioversion ( n ) | 1 (5%) | 9 (23%) | <0.05 |

| Complications (lead problems/pneumothorax) ( n ) | 1/1 (10%) | 1/1 (5%) | ns |

| Oversensing ( n ) | 10 (45%) | 5 (13%) | =0.02 |

| Inappropriate ATP ( n ) | 4 (20%) | 1 (2%) | <0.05 |

| Inappropriate cardioversion ( n ) | 5 (20%) | 2 (4%) | =0.06 |

| Death ( n ) | 1 (5%) | 8 (21%) | <0.05 |

| . | TOF ( n = 25) . | DCM ( n = 39) . | P -value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean follow-up (days) (SD) | 695 (493) | 841 (570) | ns |

| Appropriate ATP ( n ) | 4 (20%) | 5 (13%) | ns |

| Appropriate cardioversion ( n ) | 1 (5%) | 9 (23%) | <0.05 |

| Complications (lead problems/pneumothorax) ( n ) | 1/1 (10%) | 1/1 (5%) | ns |

| Oversensing ( n ) | 10 (45%) | 5 (13%) | =0.02 |

| Inappropriate ATP ( n ) | 4 (20%) | 1 (2%) | <0.05 |

| Inappropriate cardioversion ( n ) | 5 (20%) | 2 (4%) | =0.06 |

| Death ( n ) | 1 (5%) | 8 (21%) | <0.05 |

ATP, anti-tachycardia pacing; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy.

| . | TOF ( n = 25) . | DCM ( n = 39) . | P -value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean follow-up (days) (SD) | 695 (493) | 841 (570) | ns |

| Appropriate ATP ( n ) | 4 (20%) | 5 (13%) | ns |

| Appropriate cardioversion ( n ) | 1 (5%) | 9 (23%) | <0.05 |

| Complications (lead problems/pneumothorax) ( n ) | 1/1 (10%) | 1/1 (5%) | ns |

| Oversensing ( n ) | 10 (45%) | 5 (13%) | =0.02 |

| Inappropriate ATP ( n ) | 4 (20%) | 1 (2%) | <0.05 |

| Inappropriate cardioversion ( n ) | 5 (20%) | 2 (4%) | =0.06 |

| Death ( n ) | 1 (5%) | 8 (21%) | <0.05 |

| . | TOF ( n = 25) . | DCM ( n = 39) . | P -value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean follow-up (days) (SD) | 695 (493) | 841 (570) | ns |

| Appropriate ATP ( n ) | 4 (20%) | 5 (13%) | ns |

| Appropriate cardioversion ( n ) | 1 (5%) | 9 (23%) | <0.05 |

| Complications (lead problems/pneumothorax) ( n ) | 1/1 (10%) | 1/1 (5%) | ns |

| Oversensing ( n ) | 10 (45%) | 5 (13%) | =0.02 |

| Inappropriate ATP ( n ) | 4 (20%) | 1 (2%) | <0.05 |

| Inappropriate cardioversion ( n ) | 5 (20%) | 2 (4%) | =0.06 |

| Death ( n ) | 1 (5%) | 8 (21%) | <0.05 |

ATP, anti-tachycardia pacing; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy.

Discussion

The present data demonstrate that patients with repaired TOF receiving an ICD have a high rate of inappropriate discharges, mostly for SVTs, and a lower rate of appropriate discharges when compared with patients with DCM. Tetralogy of Fallot patients had a higher rate of appropriate ATP therapies than those with DCM.

Sudden cardiac death in congenital heart disease

Sudden cardiac death is the single most common cause of mortality late after repair of TOF, 14–18 accounting for 30% of deaths in TOF patients over 15 years of follow-up. 1 Absolute death rates in this population remain very low, but are still 25–100 times higher than that of an age-matched population. Although the SCD of an otherwise relatively healthy young person is a catastrophic event, such that aggressive preventative therapy might seem proportional, ICD therapy is expensive and carries inherent physical and psychological risks.

For the current adult TOF cohort, the risk factors for ventricular arrhythmias and SCD, (although in all of the studies, SCD makes up very few of the censor events) include absolute QRS duration ≥180 ms, increasing QRS duration, 19 older age at first repair, pulmonary regurgitation and RV dilatation, 16 , 20 , 21 frequent ventricular ectopic beats, 21 increased RV systolic pressures, 4 , 21 , 22 complete heart block, 21 , 23 increased JT dispersion, 24 , 25 and impaired heart rate variability. 26 Other predictors of clinical arrhythmia include late gadolinium enhancement on MRI scan 27 and left ventricular dysfunction. 28 Many of these variables are merely markers of increased severity of RV dilatation and dysfunction as a result of chronic pulmonary incompetence, and it is too early to tell whether newer, more conservative approaches to RV outflow tract obstruction with less long-term pulmonary regurgitation will improve long-term haemodynamic and electrophysiological outcomes. Some patients with little RV dilatation develop ventricular arrhythmias associated with scar in the RV and may not be identified with these non-specific factors.

Electrophysiological studies in congenital heart disease

The use of EPS in patients with DCM has largely been discarded as a prognostic indicator. 29 However, in CHD, EPS continues to be used to try to assess patients' arrhythmic risk. No useful mortality data are available from most prospective studies because of small patient numbers and low event rates, but up to 35% of patients have haemodynamically important inducible VT, 30 , 31 associated with wide QRS, increased RV dimensions, and increased QT dispersion. The only study large enough ( n = 252) to provide accurate mortality data based on 15 years of follow-up confirmed inducible VT in 37% and event-free survival in the inducible group of 50% compared with 90% in those without inducible VT. However, there were only 17 deaths (7%) over 15 years, although in those with inducible polymorphic VT ( n = 11), the SCD rate at 15 years was 40%. 19

Implantable defibrillators in congenital heart disease

Risk–benefit ratio

Although there is a lack of evidence of mortality benefit of ICDs in TOF patients, there is anecdotal suggestion of morbidity benefit. Medical therapy for symptomatic VT is often unsatisfactory in this group even if the side effects of amiodarone in such young patients are accepted, 32 many patients continue to have episodes of palpitations because of VT. In patients with TOF with frequent episodes of ATP-responsive VT, device implantation can significantly improve their quality of life by avoiding hospital admission and maintenance of their driving licence.

Despite optimal programming and dual-lead systems in all patients, our TOF group suffered an inappropriate shock rate of 20%. Patients with repaired TOF are generally younger than their DCM counterparts, and RV dysfunction has less effect on physical functioning than left ventricular dysfunction. Hence, such patients are likely to be more active than other groups receiving ICDs which increase the risk of sinus tachycardia at rates falling in the VT detection zones, thereby increasing the risk of inappropriate VT therapies. Atrial dysrhythmias, as a result of the surgical atriotomy, 33 are also a frequent cause of inappropriate therapy, and the hypertrophied and dilated RV in TOF increases the risk of far-field sensing of the QRS complex. Consistent with these frequently occurring factors in TOF patients, the largest retrospective study so far published suggests a 30% inappropriate ATP or shock rate in 121 patients. 34 Other complications include a higher lead failure rate and the ongoing risk of infection due to numerous generator replacements in these young patients. Finally, the onset of ventricular dysrhythmias and ICD implantation has important lifestyle implications. Some patients (particularly thin young women) find even current ICDs unacceptably bulky. There are stringent licensing authority restrictions about driving and particular types of employment may be threatened. Patients with ICDs are more likely to report ICD-related lower quality of life and depression, with a greater prevalence in young patients. 35 , 36 This problem may be exacerbated in patients with CHD as a consequence of their lifelong cardiac condition and childhood experiences.

Outcomes

Our data demonstrate a low frequency of events with only one appropriate cardioversion and one death after a mean of 2 years of follow-up. This contrasts with the higher appropriate discharge rate in patients with DCM. Although our cohort is small, and limited by a modest period of follow-up, the indications for implantation and period of follow-up were similar between the groups, yet the mortality difference between the groups was significantly different. In the absence of randomized trials in patients with TOF, a comparison with the DCM population is relevant. The mean 1 year mortality for DCM patients recruited to the control arms of the primary prevention arms of ICD studies was 9%. 37 In contrast, the SCD mortality in TOF is <2% per year in most studies and increases to 6% in patients followed for more than 30 years. In patients with DCM, no single trial has demonstrated a clear benefit of ICD therapy on mortality. 38 It required a large meta-analysis with over 1800 patients to identify a statistically significant benefit. 37 Data on secondary prevention remains neutral, despite meta-analysis, probably hampered by small numbers. Our results and data from other published reports suggest that the arrhythmic mortality from SCD in TOF patients is even lower than that of DCM patients.

Finally, and particularly relevant to the TOF population, in the ICD arm of DEFINITE, the largest randomized trial of primary prevention in DCM, 33 of 229 patients received 70 ‘appropriate’ therapies, but there were only 15 sudden deaths in the 229 patients receiving medical therapy. This implies that therapies delivered for VT are not always life saving, because much VT will terminate spontaneously. 39 This is likely to be more common in the TOF patients than in DCM patients.

Conclusion

Full implementation of current guidelines suggesting that ICD implantation as a therapy for patients with TOF (or any CHD) would lead to a large increase in ICD implants in low risk, young individuals with no proven mortality benefit, and great potential for physical and psychological damage. Before the NICE guidelines can be adopted for all individuals with TOF and other potentially arrhythmogenic congenital heart defects, the mortality and morbidity benefits and psychological aspects of ICD therapy in this group should be evaluated more closely.

Limitations

Our study is limited by its retrospective nature, small numbers, and short duration of follow-up. However, our data were collected in a consecutive fashion and no patients were excluded. Furthermore, given the high rate of mortality in patients with DCM, it is likely that a longer duration of follow-up would further expose the differences between the populations in terms of total mortality and sudden death. Our analysis using DCM and TOF patients is not without its limitations, but DCM patients represent the nearest appropriate comparator group for whom randomized controlled data are available.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Ms Rachel Mundell and Mrs Eve Butterfield for secretarial assistance. The data relating to patients with Tetralogy of Fallot have also been included in a multicentre analysis of event rates in patients with congenital heart disease and ICDs.

Conflict of interest: none declared.