-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Béatrice Brembilla-Perrot, Frédéric Chometon, Laurent Groben, Charif Tatar, Jean-Dominique Luporsi, Julien Bertrand, Olivier Huttin, Daniel Beurrier, Sonia Ammar, Juanico Cedano, Nacima Benzaghou, Marius Andronache, Rouzbeh Valizadeh, Arnaud Terrier De La Chaise, Pierre Louis, Olivier Selton, Olivier Claudon, François Marçon, Are the results of electrophysiological study different in patients with a pre-excitation syndrome, with and without syncope?, EP Europace, Volume 10, Issue 2, February 2008, Pages 175–180, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eum300

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Syncope in Wolff–Parkinson–White (WPW) syndrome may reveal an arrhythmic event or is not WPW syndrome related. The aim of the study is to evaluate the results of electrophysiological study in WPW syndrome according to the presence or not of syncope and the possible causes of syncope.

Among 518 consecutive patients with diagnosis of WPW syndrome, 71 patients, mean age 34.5 ± 17, presented syncope. Transoesophageal electrophysiological study in control state and after isoproterenol infusion was performed in the out-patient clinic. Atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia (AVRT) was more frequently induced than in asymptomatic patients ( n = 38, 53.5%, P < 0.01), less frequently than in those with tachycardia; atrial fibrillation (AF) and/or antidromic tachycardia (ATD) was induced in 28 patients (39%) more frequently ( P < 0.05) than in asymptomatic patients or those with tachycardia. The incidence of high-risk form [rapid conduction over accessory pathway (AP) and AF or ATD induction] was higher in syncope group ( n = 18, 25%, P < 0.001) than in asymptomatic subjects (8%) or those with tachycardias (7.5%). Maximal rate conducted over AP was similar in patients with and without syncope, and higher in patients with spontaneous AF, but without syncope. Results were not age-related.

Tachycardia inducibility was higher in patients with syncope than in the asymptomatic group. The incidence of malignant WPW syndrome was higher in patients with syncope than in asymptomatic or symptomatic population, but the maximal rate conducted over AP was not higher and another mechanism could be also implicated in the mechanism of syncope.

Introduction

Syncope in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome may be considered as a premonitory event of life-threatening arrhythmias or may be an event without correlation with WPW syndrome.

Few studies report syncope associated with WPW syndrome. Syncope was shown, at first, not to increase the incidence of pre-excitation syndrome at risk of life-threatening arrhythmias in adults. 1 However, in patients younger than 25 years, high risk of atrial fibrillation (AF) induction with a rapid ventricular response has been reported. 2

Since accessory pathway can be safely treated by catheter ablation, 3 WPW syndrome electrophysiological study (EPS) in patients presenting with syncope is recommended.

Methods

Population of study

Five hundred and twenty-one patients, mean age 35 ± 17 years, were consecutively diagnosed of having overt permanent pre-excitation syndrome on surface ECG. Subjects were diagnosed and recruited in a single centre, between 1990 and 2007.

One hundred and seventy-nine patients were asymptomatic and EPS was indicated for prognostic evaluation. Two hundred and seventy patients had tachycardia which could be documented or not; 18 of them had a documented AF; they had no dizziness or syncope; the study was indicated for the prognostic evaluation of pre-excitation syndrome and the assessment of the tachycardia. Seventy-two patients (14%) had syncope, defined as a short loss of consciousness, usually leading to falling. The onset of syncope was relatively rapid, and the subsequent recovery was spontaneous, complete, and usually prompt. Electrophysiological study was performed for syncope in those patients. Syncope was the first event of the pre-excitation syndrome in 39 patients and pre-excitation syndrome was diagnosed at the time of the syncope. Thirty-five patients had presented from 2 to 5 episodes of presyncope before syncope. Twenty-nine of them had a feeling of palpitations or tachycardia before or at the time of syncope. Fast AF was documented in eight of them.

Methods

Informed consent was obtained from the patients and in the case of children, from children and their parents.

The EPS was performed by transesophageal route in out-patient clinic except in patients with documented arrhythmia ( n = 8). The patients were not sedated. The study was performed in a room for electrophysiology, which has adequate life-saving equipment and qualified medical staff, after clear explanations of the technique. Patients were informed of the possibility of chest pain due to pacing current of more than 12–15 mA.

Oesophageal catheter (Fiab catheter, Ela medical, France) was passed through oral cavity. Our protocol was previously reported. 4 , 5

Surface electrocardiograms and oesophageal electrogram were simultaneously recorded on paper at speeds of 25 or 100 mm/s (Midas/Marquette-Hellige and then Bard system). Cardiac stimulation was initially performed with a programmable stimulator (Explorer 2000, Ela) which was connected to an Ela pulse amplifier that can deliver pulses at a width of 16 ms, with a 10 to 29 mA output; mean output used in this population was 17 ± 5 mA. Recently, we have used a biphasic stimulator (Micropace, Bard France) used for intracardiac study. Pulses of 10 ms duration were used; output varied from 9 to 20 mA (mean 11 ± 2 mA).

Incremental atrial pacing was performed until type I second degree atrioventricular block occurred. Programmed atrial stimulation at a basic cycle length of 600 and 400 ms with the introduction of one and two extrastimuli was performed. When a fast supraventricular tachycardia was induced, the protocol was stopped. In the absence of induction of a tachycardia conducted through the accessory pathway at a rate higher than 250 bpm, isoproterenol (0.02–1 µg/min 1 ) was infused then to increase the sinus rate to at least 130 bpm and the pacing protocol was repeated. 6 , 7

Arterial blood pressure was continuously monitored during the study by an external sphygmomanometer (Baxter, Japan).

Patients with induced atrial arrhythmias were monitored until sinus rhythm was restored. All patients were leaving hospital after the EPS. Beta-blockers were prescribed in patients with inducible re-entrant tachycardia. An association of class I antiarrhythmic drug (as flecaïnide) combined with small doses of beta-blockers was preferred in patients with a malignant form of WPW syndrome until radiofrequency accessory pathway ablation was performed.

Head-up tilt testing without provocative drugs was performed in 39 syncope patients. After 20 min in supine position, electric table was moved to an upright position for 40 min or until syncope occurred. The inclination was of 80°. The ECG was continuously monitored and the arterial blood pressure was measured by an external sphygmomanometer.

Definitions

The accessory pathway's location was determined with the 12-lead ECG recorded in maximal pre-excitation.

Sustained AF or reciprocating tachycardia was defined as a tachycardia that lasted longer than 1 min.

Conduction over the accessory atrioventricular connection was evaluated by the measurement of the shortest atrial cycle length at which there was one-to-one conduction over the accessory connection and the shortest atrial tachycardia cycle length at which there was one-to-one conduction over the accessory connection.

Accessory pathway's effective refractory period was determined at a cycle length of 600 ms and 400 ms in control state and only 400 ms after isoproterenol.

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome was considered as malignant and with a risk of sudden death when the following association was observed: the shortest RR interval between pre-excited beats was <250 ms in the control state or <200 ms during isoproterenol infusion 7 and sustained AF or tachycardia or antidromic tachycardia was induced. Orthodromic tachycardia induction was not considered as a criterium for a high risk form of pre-excitation syndrome.

Inducible reciprocating tachycardia or other supraventricular tachyarrhythmia was a possible cause for syncope, if tachycardia was sustained, either spontaneously stopped but reproducible or a permanent tachycardia, associated with a decrease in systolic arterial blood pressure of at least 30% or by at least 20 mmHg and inducing symptoms similar to those preceding spontaneous syncope.

Electrophysiological study was considered as negative if no tachycardia was induced and a relatively long refractory period of accessory pathway was noted.

Head-up tilt testing was considered as positive, if syncope was induced by the tilting or a decrease in systolic blood pressure to below 90 mmHg associated with symptoms of impending syncope. 8 , 9

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis used the Student's t paired test for quantitative data and the χ 2 test for discrete variables and ordinal tests. A P -value <0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

Feasibility of transoesophageal study

Electrophysiological study was not feasible in three patients, one with syncope, one asymptomatic patient, and one with tachycardia, either because it was not possible to introduce the oesophageal catheter because of a nausea reflex or because left atrium could not be paced through the oesophagus. All patients left hospital after the EPS; however, three patients with syncope and six other patients required the flecainide infusion to stop an induced AF and patients were discharged only after the restoration of sinus rhythm. In other patients, the mean duration of EPS ranged from 5 to 30 min (mean 12 ± 3).

Results of transoesophageal electrophysiological study in patients with syncope

We report the data of 71 patients in whom the study could be performed. Atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia (AVRT) was induced in the case of 38 patients (53.5%). Isoproterenol infusion was required in 12 patients. Atrial fibrillation was induced in the case of 22 patients and antidromic tachycardia in 6 patients; isoproterenol infusion was required in 10 patients. Both tachycardias, AVRT and AF were induced in the case of 10 patients; isoproterenol was required in 4 of them.

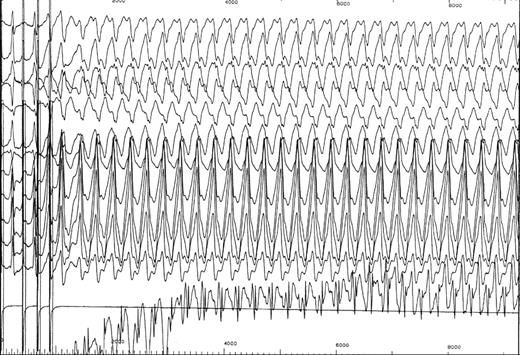

Overall 56 of 71 syncope patients (79%) had an inducible tachycardia (either AVRT, AF, antidromic tachycardia or all). The tachycardia's rate was very fast (more than 240 bpm) (28 patients); 22 patients presented a vasovagal reaction occurring after the end of the tachycardia. Atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia was followed by a short episode of sinus tachycardia and then a sinus or junctional bradycardia while the arterial blood pressure was decreasing ( Figure 1 ).

Atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia followed by a short episode of sinus tachycardia and then a sinus bradycardia.

Forty-nine patients recognized the induced tachycardia as the symptoms associated with syncope, but some of them had also these symptoms several years earlier before the occurrence of syncope.

Rapid conduction over the accessory pathway (more than 240 bpm in the basal state and/or more than 300 bpm after isoproterenol) was noted in 18 patients (25%).

At the end of the EPS; only 15 patients (21%) suffered from benign form of pre-excitation syndrome; they had no inducible tachycardia and the accessory pathway refractory period was long. In opposition, 18 patients (25%) were considered as having a malignant form of pre-excitation syndrome; they had an inducible AF or antidromic tachycardia with short RR intervals between pre-excited beats ( Figure 2 ). Among these patients, six had also inducible AVRT.

Induction of antidromic tachycardia with short RR intervals between pre-excited beats (200 ms).

Data of head-up tilt test in syncope patients

Thirteen syncope patients with induced supraventricular tachycardia had a positive tilt testing. Eleven patients with a negative EPS had a positive tilt testing. The remaining 15 patients had a negative head-up tilt test.

Comparisons of clinical data in patients with syncope and without syncope

Sex ratio was equal in the two groups ( Table 1 ).

Clinical data of the study population compared with remaining patients with Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome

| . | Total . | Syncope . | No symptoms . | Tachycardia . | AF . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 518 | 71 | 178 | 251 | 18 |

| Age (years) | 35 ± 17 | 34.5 ± 17 | 30 ± 16 | 37 ± 16 | 49 ± 16*** |

| Male sex, % | 307 (59) | 37 (52) | 118 (66) | 140 (56) | 13 (72) |

| Left lateral AP, % | 209 (40) | 27 (38) | 42 (23.5)* | 131 (52)* | 9 (50) |

| Left PS AP, % | 107 (21) | 15 (21) | 47 (26) | 42 (16) | 3 (17) |

| Right PS AP, % | 127 (24.5) | 19 (27) | 60 (34) | 45 (18) | 3 (17) |

| Anteroseptal AP, % | 22 (4) | 5 (7) | 18 (10) | 19 (7.5) | |

| Right lateral AP, % | 42 (8) | 4 (6) | 9 (5) | 7 (3) | 2 (11) |

| Other or two AP's, % | 10 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 7 (3) |

| . | Total . | Syncope . | No symptoms . | Tachycardia . | AF . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 518 | 71 | 178 | 251 | 18 |

| Age (years) | 35 ± 17 | 34.5 ± 17 | 30 ± 16 | 37 ± 16 | 49 ± 16*** |

| Male sex, % | 307 (59) | 37 (52) | 118 (66) | 140 (56) | 13 (72) |

| Left lateral AP, % | 209 (40) | 27 (38) | 42 (23.5)* | 131 (52)* | 9 (50) |

| Left PS AP, % | 107 (21) | 15 (21) | 47 (26) | 42 (16) | 3 (17) |

| Right PS AP, % | 127 (24.5) | 19 (27) | 60 (34) | 45 (18) | 3 (17) |

| Anteroseptal AP, % | 22 (4) | 5 (7) | 18 (10) | 19 (7.5) | |

| Right lateral AP, % | 42 (8) | 4 (6) | 9 (5) | 7 (3) | 2 (11) |

| Other or two AP's, % | 10 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 7 (3) |

Study not possible in three patients, one with syncope, one asymptomatic patient, and one with tachycardia, excluded from the data.

AP, accessory pathway; PS, posteroseptal; AF, atrial fibrillation.

The statistical data indicated the comparisons with the group with syncope (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001).

Clinical data of the study population compared with remaining patients with Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome

| . | Total . | Syncope . | No symptoms . | Tachycardia . | AF . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 518 | 71 | 178 | 251 | 18 |

| Age (years) | 35 ± 17 | 34.5 ± 17 | 30 ± 16 | 37 ± 16 | 49 ± 16*** |

| Male sex, % | 307 (59) | 37 (52) | 118 (66) | 140 (56) | 13 (72) |

| Left lateral AP, % | 209 (40) | 27 (38) | 42 (23.5)* | 131 (52)* | 9 (50) |

| Left PS AP, % | 107 (21) | 15 (21) | 47 (26) | 42 (16) | 3 (17) |

| Right PS AP, % | 127 (24.5) | 19 (27) | 60 (34) | 45 (18) | 3 (17) |

| Anteroseptal AP, % | 22 (4) | 5 (7) | 18 (10) | 19 (7.5) | |

| Right lateral AP, % | 42 (8) | 4 (6) | 9 (5) | 7 (3) | 2 (11) |

| Other or two AP's, % | 10 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 7 (3) |

| . | Total . | Syncope . | No symptoms . | Tachycardia . | AF . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 518 | 71 | 178 | 251 | 18 |

| Age (years) | 35 ± 17 | 34.5 ± 17 | 30 ± 16 | 37 ± 16 | 49 ± 16*** |

| Male sex, % | 307 (59) | 37 (52) | 118 (66) | 140 (56) | 13 (72) |

| Left lateral AP, % | 209 (40) | 27 (38) | 42 (23.5)* | 131 (52)* | 9 (50) |

| Left PS AP, % | 107 (21) | 15 (21) | 47 (26) | 42 (16) | 3 (17) |

| Right PS AP, % | 127 (24.5) | 19 (27) | 60 (34) | 45 (18) | 3 (17) |

| Anteroseptal AP, % | 22 (4) | 5 (7) | 18 (10) | 19 (7.5) | |

| Right lateral AP, % | 42 (8) | 4 (6) | 9 (5) | 7 (3) | 2 (11) |

| Other or two AP's, % | 10 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 7 (3) |

Study not possible in three patients, one with syncope, one asymptomatic patient, and one with tachycardia, excluded from the data.

AP, accessory pathway; PS, posteroseptal; AF, atrial fibrillation.

The statistical data indicated the comparisons with the group with syncope (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001).

Patients with spontaneous documented AF were older.

Left lateral accessory pathway location was more frequent in patients with syncope than in asymptomatic patients but was less frequent than in symptomatic patients without syncope. Other accessory pathway locations did not differ significantly.

Comparisons of electrophysiological data in patients with syncope and without syncope

Patients with syncope differed from asymptomatic patients by a higher incidence of inducible AVRT ( P < 0.001), inducible AF ( P < 0.05), and malignant forms ( P < 0.01) ( Table 2 ).

Electrophysological data of the study population compared to remaining patients with Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome

| . | Total . | Syncope . | No symptoms . | Tachycardia . | AF . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 518 | 71 | 178 | 251 | 18 |

| AVRT induction, % | 288 (56) | 38 (53.5)** | 18 (10) | 233 (93) | 8 (44) |

| AF induction, % | 111 (25) | 22 (31)* | 33 (18.5) | 40 (16) | 14 (78) |

| Antidromic T, % | 25 (5) | 6 (8) | 7 (4) | 10 (4) | 3 (17) |

| Max rate CS | 194 ± 58 | 195 ± 58 | 190 ± 57 | 193 ± 62 | 237 ± 57** |

| Max rate iso | 244 ± 64 | 244 ± 73 | 238 ± 63 | 251 ± 67 | 280 ± 55* |

| Malignant form, % | 91 (20) | 18 (25)*** | 15 (8) | 19 (7.5) | 7 (39) |

| . | Total . | Syncope . | No symptoms . | Tachycardia . | AF . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 518 | 71 | 178 | 251 | 18 |

| AVRT induction, % | 288 (56) | 38 (53.5)** | 18 (10) | 233 (93) | 8 (44) |

| AF induction, % | 111 (25) | 22 (31)* | 33 (18.5) | 40 (16) | 14 (78) |

| Antidromic T, % | 25 (5) | 6 (8) | 7 (4) | 10 (4) | 3 (17) |

| Max rate CS | 194 ± 58 | 195 ± 58 | 190 ± 57 | 193 ± 62 | 237 ± 57** |

| Max rate iso | 244 ± 64 | 244 ± 73 | 238 ± 63 | 251 ± 67 | 280 ± 55* |

| Malignant form, % | 91 (20) | 18 (25)*** | 15 (8) | 19 (7.5) | 7 (39) |

AVRT, atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia; AF, atrial fibrillation; T, tachycardia; Max rate CS, maximal rate (bpm) conducted over the accessory pathway in control state; Max rate iso, maximal rate conducted over the accessory pathway after isoproterenol infusion. (*P, 0.05; **P, 0.01; ***P, 0.001).

Electrophysological data of the study population compared to remaining patients with Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome

| . | Total . | Syncope . | No symptoms . | Tachycardia . | AF . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 518 | 71 | 178 | 251 | 18 |

| AVRT induction, % | 288 (56) | 38 (53.5)** | 18 (10) | 233 (93) | 8 (44) |

| AF induction, % | 111 (25) | 22 (31)* | 33 (18.5) | 40 (16) | 14 (78) |

| Antidromic T, % | 25 (5) | 6 (8) | 7 (4) | 10 (4) | 3 (17) |

| Max rate CS | 194 ± 58 | 195 ± 58 | 190 ± 57 | 193 ± 62 | 237 ± 57** |

| Max rate iso | 244 ± 64 | 244 ± 73 | 238 ± 63 | 251 ± 67 | 280 ± 55* |

| Malignant form, % | 91 (20) | 18 (25)*** | 15 (8) | 19 (7.5) | 7 (39) |

| . | Total . | Syncope . | No symptoms . | Tachycardia . | AF . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 518 | 71 | 178 | 251 | 18 |

| AVRT induction, % | 288 (56) | 38 (53.5)** | 18 (10) | 233 (93) | 8 (44) |

| AF induction, % | 111 (25) | 22 (31)* | 33 (18.5) | 40 (16) | 14 (78) |

| Antidromic T, % | 25 (5) | 6 (8) | 7 (4) | 10 (4) | 3 (17) |

| Max rate CS | 194 ± 58 | 195 ± 58 | 190 ± 57 | 193 ± 62 | 237 ± 57** |

| Max rate iso | 244 ± 64 | 244 ± 73 | 238 ± 63 | 251 ± 67 | 280 ± 55* |

| Malignant form, % | 91 (20) | 18 (25)*** | 15 (8) | 19 (7.5) | 7 (39) |

AVRT, atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia; AF, atrial fibrillation; T, tachycardia; Max rate CS, maximal rate (bpm) conducted over the accessory pathway in control state; Max rate iso, maximal rate conducted over the accessory pathway after isoproterenol infusion. (*P, 0.05; **P, 0.01; ***P, 0.001).

Patients with syncope differed from patients with documented or presumed AVRT by lower incidence of AVRT ( P < 0.001), higher incidence of induced AF ( P < 0.05), and malignant form of pre-excitation syndrome ( P < 0.001).

Patients with syncope differed from those with spontaneous haemodynamically well-tolerated AF by less frequent AF induction and lower maximal rate conducted through the accessory pathway in control state and after isoproterenol than in patients with spontaneous AF and no syncope.

Differences in electrophysiological data related to the patient's age

There were no differences between children and teenagers and adults; for 3 patients, respectively 66, 67 and 71 years old, syncope was the first event and was associated with the presence of a malignant form of preexcitation syndrome ( Table 3 ).

Clinical and electrophysiological data of patients with syncope according to the patient's age

| . | 6–19 years . | 20–85 years . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 21 | 50 | |

| Age (years) | 15 ± 3 | 43 ± 14 | |

| Male sex, % | 14 (67) | 23 (46) | NS |

| AVRT induction, % | 9 (43) | 28 (56) | NS |

| AF induction, % | 6 (28.5) | 16 (32) | NS |

| Antidromic T, % | 3 (14) | 3 (6) | NS |

| Max rate CS (bpm) | 194 ± 59 | 196 ± 58 | NS |

| Max rate iso (bpm) | 235 ± 79 | 245 ± 71 | NS |

| Malignant form, % | 7 (33) | 11 (22) | NS |

| . | 6–19 years . | 20–85 years . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 21 | 50 | |

| Age (years) | 15 ± 3 | 43 ± 14 | |

| Male sex, % | 14 (67) | 23 (46) | NS |

| AVRT induction, % | 9 (43) | 28 (56) | NS |

| AF induction, % | 6 (28.5) | 16 (32) | NS |

| Antidromic T, % | 3 (14) | 3 (6) | NS |

| Max rate CS (bpm) | 194 ± 59 | 196 ± 58 | NS |

| Max rate iso (bpm) | 235 ± 79 | 245 ± 71 | NS |

| Malignant form, % | 7 (33) | 11 (22) | NS |

Clinical and electrophysiological data of patients with syncope according to the patient's age

| . | 6–19 years . | 20–85 years . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 21 | 50 | |

| Age (years) | 15 ± 3 | 43 ± 14 | |

| Male sex, % | 14 (67) | 23 (46) | NS |

| AVRT induction, % | 9 (43) | 28 (56) | NS |

| AF induction, % | 6 (28.5) | 16 (32) | NS |

| Antidromic T, % | 3 (14) | 3 (6) | NS |

| Max rate CS (bpm) | 194 ± 59 | 196 ± 58 | NS |

| Max rate iso (bpm) | 235 ± 79 | 245 ± 71 | NS |

| Malignant form, % | 7 (33) | 11 (22) | NS |

| . | 6–19 years . | 20–85 years . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 21 | 50 | |

| Age (years) | 15 ± 3 | 43 ± 14 | |

| Male sex, % | 14 (67) | 23 (46) | NS |

| AVRT induction, % | 9 (43) | 28 (56) | NS |

| AF induction, % | 6 (28.5) | 16 (32) | NS |

| Antidromic T, % | 3 (14) | 3 (6) | NS |

| Max rate CS (bpm) | 194 ± 59 | 196 ± 58 | NS |

| Max rate iso (bpm) | 235 ± 79 | 245 ± 71 | NS |

| Malignant form, % | 7 (33) | 11 (22) | NS |

Follow-up

Patients with induced tachycardia were either treated medically with flecainide and beta-blockers or by catheter ablation of the accessory pathway; the choice depended on the age and the height of the child, patient's preferences, the location of the accessory pathway, and the time of recruitment. Since 2000, catheter ablation was the first therapeutic option in all teenagers or adults with inducible tachycardia.

Patients with negative EPS were generally not treated, unless indicated for sports activities.

Patients' follow-up ranged from 8 months to 9 years (mean 5 ± 2 years).

Accessory pathway catheter ablation was performed in 23 patients, 20 with inducible tachycardia and 3 with a negative EPS; other patients with induced tachycardia were treated by flecainide associated or not with beta-blockers.

Patients with induced AF or AVRT had no recurrence of syncope either after accessory pathway ablation ( n = 20), but also after antiarrhythmic drugs ( n = 22); syncope or dizziness recurred in three patients without inducible arrhythmias in whom catheter ablation of the accessory pathway was performed at patient's demand.

Other patients without inducible tachycardia were not treated and dizziness recurred in three patients.

Discussion

We report a low incidence of syncope in WPW syndrome (14%), but pre-excitation syndrome was frequently directly implicated in the presumed mechanism of syncope. The incidence of forms at high risk of life-threatening arrhythmias was higher in patients with syncope than in asymptomatic patients and in symptomatic patients without syncope. We also found that AVRT was a frequent cause of syncope. The maximal rate conducted over accessory pathway was not higher in patients with syncope than in patients without syncope and was surprisingly slower than in those with spontaneous AF but without syncope.

Syncope was not considered as clinically relevant in previous studies in WPW syndrome 10 and was not found being a clinical predictor of ventricular fibrillation in the study of Attoyan et al . 11 Some patients can present a rapid AF or other tachycardia conducted over the accessory pathway without occurrence of syncope; 10 Among WPW syndrome population, 7 of 18 patients who were admitted for AF, had malignant pre-excitation with short RR intervals between pre-excited beats and they had no dizziness or syncope. The maximal rate conducted over the accessory pathway was higher in these patients with spontaneous AF but without syncope than in those with syncope or asymptomatic subjects.

But syncope was considered as clinically relevant in the study by Paul et al . 2 They reported a syncope incidence of 19% in 74 patients with a WPW syndrome and they noted that AF with short RR intervals between pre-excited beats was frequent in patients with syncope (9/14).

Ventricular tachycardia was also reported as a possible cause of syncope in WPW syndrome. 12 However, other authors 13 , 14 reported a high risk of induction of not specific polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in 10–37% of patients with a WPW syndrome.

Electrophysiological study is now considered mandatory for identification of the patients at risk of rapid arrhythmias with good diagnostic value 15–18 and this technique was chosen in the present study. Some presumed causes for syncope were identified. As Paul et al ., 2 we report a high incidence of malignant forms of pre-excitation syndrome in patient with syncope and independently on the age of the patient. We also report higher inducibility of re-entrant tachycardia than in asymptomatic subjects. We previously reported 19 that AV nodal re-entrant tachycardia or AVRT over a concealed accessory pathway can bring about syncope by vagal reaction, occurring after termination of the tachycardia. Frequently, these patients had a vagal hypertonia with a positive tilt testing. Maximal rate conducted over accessory pathway was not higher in patients with syncope than in those without syncope. Patients with rapid spontaneous AF frequently had no syncope. The tachycardia rate probably did not explain syncope. In most patients, syncope could be related to induced tachycardia because the patient recognized the symptoms associated with syncope. Significant change in arterial blood pressure was noted either during tachycardia or just after its termination. No patients had syncope during EPS, but they felt dizzy because they were in supine position.

Syncope was considered unrelated to WPW syndrome in 15 patients and was considered of vasovagal origin in 11 patients with a negative EPS and a positive tilt testing. Epilepsy was identified in one patient who had also inducible AF. Infrahisian conduction abnormalities were identified in a second time during an intracardiac study in a 45-year-old woman who had a negative transoesophageal EPS and tilt testing. Ajmaline injection suppressed the conduction over the accessory pathway and induced complete infrahisian AV block. Similar cases were reported several years ago. 20 , 21 Syncope remained unexplained in two patients with a negative EPS and negative tilt testing.

These presumed mechanisms of syncope were not considered to be age related, 22 although some authors reported prolongation of the accessory pathway refractory period and increased induction of AF in elderly patients. 23–26 Paul et al . 2 reported a high incidence of life-threatening arrhythmias in young adults with syncope, but all patients were younger than 25 years. These results were not confirmed in our study.

The advantages of accessory pathway catheter ablation were shown for patients with AVRT 3 and in asymptomatic patients with inducible tachycardia. 27 We confirm that patients with syncope and inducible tachycardia could benefit from ablation, but we do not recommend accessory pathway ablation in patients with syncope and without inducible tachycardia. Antiarrhythmic treatment was also shown in the present study to suppress dizziness and syncope recurrence in patients with inducible tachycardia independently on the results of tilt testing.

Limits of the study

The main limit is the absence of reproduction of syncope during the EPS because the test was performed in supine position. Some patients recognized AVRT as the tachycardia that they had since several years, but the tachycardia was of short duration and was well tolerated spontaneously. We cannot explain why one of them was responsible for syncope. Was the tachycardia faster or the patient older or the patient more tired?

Among patients with induced tachycardia and positive tilt head-up tilt testing, we cannot exclude a vasovagal origin for syncope. The effects of medical or ablative treatment on the suppression of syncope which argue for the role of supraventricular tachycardia are difficult to interpret because the syncope was the first episode for most of the patients.

Tilt table testing was not performed in all patients with syncope, especially in those with a malignant form of WPW syndrome. We cannot exclude that syncope in patients with inducible rapid AF was also of vagal origin and without relationship with induced tachycardia.

The interpretation of the results of tilt table testings are limited by the diagnostic value of the technique which depends on the patient's age and the tilt table test protocol used.

We report the data of transoesophageal EPS; the method was shown to indicate similar results to those obtained by intracardiac route. 28 However, ventricular pacing cannot be performed and we could have failed the induction of some tachycardias by this method. This fact could explain that AF was induced in only 14 of 18 patients with spontaneous AF, but AF induction can also be more difficult than the induction of a re-entrant tachycardia.

In conclusion, electrophysiological data of patients with syncope clearly differed from those of asymptomatic subjects by higher tachycardia inducibility. The incidence of malignant form of WPW syndrome was higher in patients with syncope than asymptomatic or symptomatic population with a WPW syndrome and indicates a potential risk of sudden death in patients with WPW syndrome combined with syncope. Syncope should be considered as a clinically relevant symptom in pre-excitation syndrome and electrophysiological evaluation is indicated at all ranges of life. The association of tachycardia inducibility with a high vagal tone could also explain the occurrence of syncope in some patients with a pre-excitation syndrome.

Conflict of interest : none declared.