-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Anna Meta Dyrvig Kristensen, Manan Pareek, Kristian Hay Kragholm, Christian Torp-Pedersen, John William McEvoy, Eva Bossano Prescott, Temporal trends in low-dose aspirin therapy for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in European adults with and without diabetes, European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, Volume 30, Issue 12, September 2023, Pages 1172–1181, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwad092

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Aspirin therapy for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) is controversial, and guideline recommendations have changed throughout the last decades. We report temporal trends in primary prevention aspirin use among persons with and without diabetes and describe characteristics of incident aspirin users.

Using Danish nationwide registries, we identified incident and prevalent aspirin users in a population of subjects ≥40 years without CVD eligible for primary preventive aspirin therapy from 2000 through 2020. Temporal trends in aspirin users with and without diabetes were assessed, as were CVD risk factors among incident users. A total of 522 680 individuals started aspirin therapy during the study period. The number of incident users peaked in 2002 (39 803 individuals, 1.78% of the eligible population) and was the lowest in 2019 (11 898 individuals, 0.49%), with similar trends for subjects with and without diabetes. The percentage of incident users with no CVD risk factors [diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (a proxy for smoking)] decreased from 53.9% in 2000 to 30.9% in 2020. The temporal trends in prevalent aspirin users followed a unimodal curve, peaked at 7.7% in 2008, and was 3.3% in 2020. For subjects with diabetes, the peak was observed in 2009 at 38.5% decreasing to 17.1% in 2020.

Aspirin therapy for primary prevention of CVD has decreased over the last two decades. However, the drug remained used in individuals with and without diabetes, and a large proportion of individuals started on aspirin therapy had no CVD risk factors.

Lay Summary

One sentence summary

This study investigated the temporal trends in aspirin use for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in individuals with and without diabetes and found that even though the number of aspirin users has declined, the drug remains prescribed, and individuals even without cardiovascular risk factors were started on aspirin therapy.

Lay summary key findings

The number of aspirin users with and without diabetes for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease has decreased over the last two decades. Nevertheless, individuals with a low burden of cardiovascular risk factors were started on aspirin therapy.

Efforts to inform appropriate use of aspirin are needed.

See the editorial comment for this article 'Low-dose aspirin therapy for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: where are we at?', by N.R. Pugliese and S. Taddei, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwad110.

Introduction

Aspirin has been an essential drug for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) for decades, but its role in primary prevention has long been controversial.1,2 Prior to the millennium, trials of aspirin for primary prevention suggested a reduction in myocardial infarction with a limited increase in bleeding events.3,4 Aspirin was thus recommended for patients at high cardiovascular (CV) risk.5,6 With the advent of better preventive strategies, including statins, antihypertensive medications, and improvements in smoking and other lifestyle-related factors, the continued role of aspirin in the primary preventive setting was questioned. More recent randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses found little to no net clinical benefit or even net harm of aspirin in primary prevention of CVD due to an increased risk of bleeding, despite the use of low doses.7–14. Consequently, international guidelines have downgraded the use of aspirin for primary prevention of CVD.15–18 According to the 2021 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines, aspirin is not recommended in subjects with low/moderate CVD risk [Class III, level of evidence (LOE) A], but may be considered in high-risk patients with diabetes (Class IIb, LOE A).15,19

Despite the lack of net benefit, aspirin still appears to be prescribed in a large number of individuals for primary prevention of CVD.20–22 The aim of this study was to evaluate the temporal trends in incident and prevalent aspirin users in primary prevention of CVD over a 20-year period in addition to CVD and bleeding risk among incident users. We hypothesized that the use of aspirin has declined and has become more appropriate over time by targeting individuals at high CVD risk (e.g. those with diabetes) and low bleeding risk.

Methods

Data sources

Data were gathered from Danish nationwide registries. All Danish citizens are registered in the Civil Registration Registry with a unique civil registration number provided at birth or immigration, enabling cross-linkage between registries.23 We further utilized data from the Danish Registry of Medicinal Product Statistics (the national prescription registry), which holds information on all prescribed medications,24 and the Danish National Patient Registry in which all diagnoses registered at outpatient visits or hospital admissions are available.25

Study population

At-risk study population

For each calendar year from 2000 through 2020, we identified an at-risk population defined as potential candidates for primary preventive aspirin therapy (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1). This at-risk population was the Danish population aged ≥40 years, without CVD, and not currently treated with a P2Y12-receptor antagonist or an oral anticoagulant. Cardiovascular disease included prior myocardial infarction, unstable angina, stable coronary artery disease, ischaemic stroke, transient ischaemic attack, atrial flutter, atrial fibrillation, or peripheral artery disease. This at-risk population was used as the denominator for analyses of prevalent aspirin users. For analyses of incident aspirin users, the same at-risk population was used, but individuals already receiving aspirin were excluded.

Prevalent and incident primary prevention aspirin users

Low-dose aspirin [Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes B01AC06 and N02BA01] was defined as a daily dose ≤150 mg as higher doses are not used for prevention of CVD in Denmark.

For each year, individuals in the at-risk population were classified as incident users on the first day of redeeming a prescription for aspirin and could only be counted as incident users once during the study period. Prevalent aspirin users were estimated on a yearly basis and were defined as individuals redeeming ≥1 aspirin prescription annually.

Characteristics, comorbidities, and comedications

Comorbidities and comedications were defined using diagnostic codes from hospitalization or outpatient visits prior to aspirin redemption in addition to pharmacy prescription fillings within 180 days prior or equal to the day of aspirin redemption. For the at-risk population, diagnostic codes prior to January 1 each year and pharmacy prescription fillings 180 days prior to January 1 each year were used to define comorbidities and comedication.

We assessed the following CVD risk factors: diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and COPD (as a proxy for smoking). Diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and COPD were defined using diagnostic codes or prescriptions for glucose-lowering drugs, statins, inhaled anticholinergic drugs, or inhaled adrenergic-anticholinergic combination drugs, respectively. Hypertension was defined as either a diagnosis of hypertension or at least two antihypertensive drugs claimed during a period of 180 days prior to the day of redeeming aspirin or January 1 for the at-risk population. Risk factors for bleeding comprised a history of one of the following: chronic kidney disease (CKD), peptic ulcer, any prior or recent hospitalized bleeding episode, and liver disease. Recent bleeding was defined as a bleeding event within the previous 5 years.

To assess the concomitant temporal trends of medications that may affect bleeding risk, we investigated the proportion of incident users redeeming a prescription of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), glucocorticoids, and proton pump inhibitors (PPI) up to 180 days prior and after the day of aspirin redemption, respectively.

Individuals without known CVD may have been prescribed aspirin in relation to a coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) due to suspected CVD. Therefore, we conducted an analysis in which we excluded subjects starting aspirin either 30 days before or after CCTA (performed after 1 January 2008). The diagnostic report of the CCTA was not available.

Diagnostic codes used for the present study were classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, Eighth or Tenth revision (ICD-8 and ICD-10). Drug prescriptions were classified according to the ATC Classification System. The relevant ICD- and ATC-codes are listed in the Supplementary material online, Material.

Ethics

According to the Danish law, retrospective registry-based studies conducted for the sole purpose of statistics and scientific research do not require ethical approval or informed consent. However, the study is approved by the data responsible institute (Capital Region of Denmark—approval number: P-2019-348) in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation. The legislation of Statistics Denmark does not allow data sharing, but access can be granted with proper permission.

Statistical analysis

For each year throughout the study period, we estimated the percentage of prevalent and incident aspirin users relative to the entire at-risk population, in individuals with and without diabetes. We also determined the ratio of the proportion of the at-risk population with diabetes starting aspirin vs. the proportion of the at-risk population without diabetes starting aspirin. Characteristics of incident aspirin users were presented in 5-year intervals and stratified by the absence or presence of diabetes. We further examined the proportion of the at-risk population with risk factors for CVD and bleeding. Characteristics were presented as numbers with corresponding percentages for categorical variables and medians with interquartile ranges for continuous variables. Finally, for incident users, we determined the number of CV risk factors present at the time of aspirin redemption.

All data management and analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), and R, version 4.0.3 (https://www.r-project.org/).

Results

Temporal trends in incident users

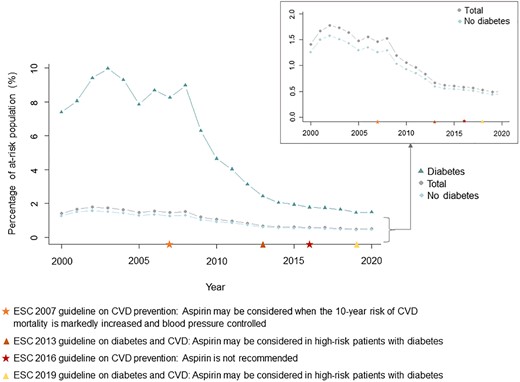

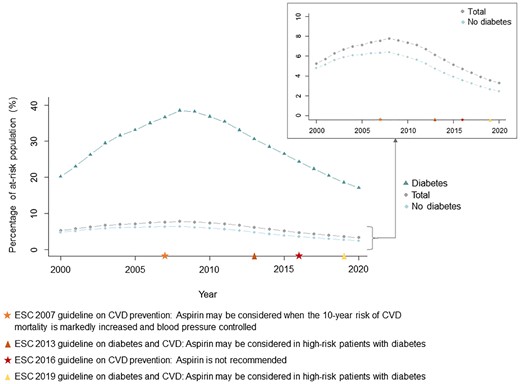

A total of 522 680 individuals started aspirin for primary prevention from January 2000 through December 2020. The proportion starting aspirin peaked in 2002 (39 803 individuals, 1.8% of the at-risk population, Figure 1) and was the lowest in 2019 (11 898 individuals, 0.5%). The trend was similar in subjects with and without diabetes. In subjects with diabetes, the proportion starting aspirin was the highest at 10.0% in 2003 and declined to 1.5% in 2020. In subjects without diabetes, the proportion starting aspirin peaked at 1.6% in 2002 and decreased to 0.5% in 2020. For all groups, the steepest decline appeared to be from 2008 to 2014, with a more gradual decline from 2014 to 2020. Temporal trends were similar across age groups (Figure 2). The ratio of aspirin initiation in individuals with diabetes vs. without diabetes peaked at 6.9 in 2008, decreased to 3.3 in 2016, and did not change substantially thereafter (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2).

Temporal trends in incident users of aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. The figure shows the proportion of at-risk individuals (without cardiovascular disease and not currently treated with antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs) starting aspirin therapy in total (grey circles) and the proportion of at-risk individuals with and without diabetes starting aspirin therapy (diabetes: green triangles, no diabetes: blue rhombuses). Temporal markers of the European Society of Cardiology guidelines on aspirin in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease are presented. CVD, cardiovascular disease; ESC, European Society of Cardiology.

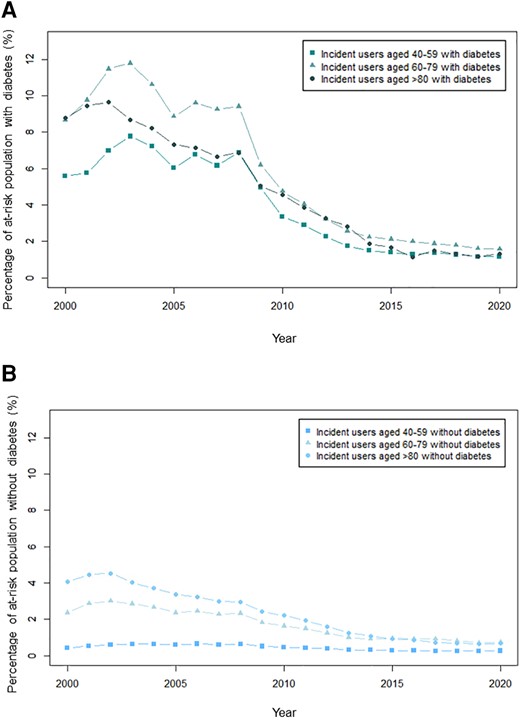

Proportion of at-risk individuals starting aspirin therapy stratified by age in (A): individuals with diabetes and (B): individuals without diabetes. The figures show the proportion of at-risk individuals starting aspirin therapy stratified by age group 40–59, 60–79, and >80.

Characteristics of incident users

Characteristics of incident aspirin users stratified by 5-year intervals and diabetes are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Incident aspirin users were primarily started at a dose of 75 mg. The proportion increased from 47.2% in individuals starting aspirin in the period from 2000 through 2004 to 95.1% in the period from 2015 through 2020 (Table 1). Compared with the at-risk population, incident aspirin users had a higher CVD and bleeding risk (Table 1 and Supplementary material online, Table S1). An increasing proportion of incident users were males, had hypercholesterolemia, COPD, CKD, and liver disease (Table 1, Supplementary material online, Figures S3 and S4). The proportion with diabetes appeared to remain unchanged over time (Table 1, Supplementary material online, Figures S3 and S5). An increasing proportion of incident users had a prior bleeding episode, whereas the proportion with a recent bleeding episode did not change substantially (Table 1, Supplementary material online, Figure S6). Similar trends in CVD and bleeding risk factors were observed in the population not prescribed aspirin with the exception of an increase in the proportion of individuals with diabetes and hypertension and a rising age (see Supplementary material online, Table S1).

| . | 2000–04 . | 2005–09 . | 2010–14 . | 2015–20 . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, no (%) | 184 416 (35.3) | 162 907 (31.2) | 96 172 (18.4) | 79 185 (15.1) | 522 680 (100) |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 68.6 (59.5, 77.2) | 65.7 (58.0, 74.5) | 65.9 (57.4, 73.9) | 66.0 (57.0, 73.1) | 66.7 (58.3, 75.2) |

| Male sex, no (%) | 88 390 (47.9) | 81 103 (49.8) | 48 554 (50.5) | 43 105 (54.4) | 261 152 (50.0) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, no (%) | |||||

| Diabetes | 25 297 (13.7) | 25 943 (15.9) | 13 740 (14.3) | 10 937 (13.8) | 75 917 (14.5) |

| Hypertension | 64 973 (35.2) | 66 072 (40.6) | 39 551 (41.1) | 30 620 (38.7) | 201 216 (38.5) |

| Hyper-cholesterolemia | 26 739 (14.5) | 61 048 (37.5) | 41 844 (43.5) | 37 767 (47.7) | 167 398 (32.0) |

| COPD | 2498 (1.4) | 2825 (1.7) | 1992 (2.1) | 2026 (2.6) | 9341 (1.8) |

| ≥1 cardiovascular risk factor | 95 006 (51.5) | 106 022 (65.1) | 65 232 (67.8) | 54 427 (68.7) | 320 687 (61.4) |

| Bleeding risk factors, no (%) | |||||

| Prior bleeding event | 16 002 (8.7) | 16 926 (10.4) | 12 218 (12.7) | 11 474 (14.5) | 56 620 (10.8) |

| Recent bleeding event | 10 236 (5.6) | 8806 (5.4) | 5610 (5.8) | 4689 (5.9) | 29 341 (5.6) |

| Prior peptic ulcer | 8283 (4.5) | 7080 (4.3) | 4139 (4.3) | 2941 (3.7) | 22 443 (4.3) |

| Liver disease | 2498 (1.4) | 2825 (1.7) | 1992 (2.1) | 2026 (2.6) | 9341 (1.8) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4012 (2.2) | 3370 (2.1) | 2528 (2.6) | 2656 (3.4) | 12 566 (2.4) |

| ≥ 1 bleeding risk factor | 26 197 (14.2) | 25 739 (15.8) | 17 812 (18.5) | 16 407 (20.7) | 86 155 (16.5) |

| Aspirin dose, no (%) | |||||

| 75 mg | 87 058 (47.2) | 136 720 (83.9) | 89 681 (93.3) | 75 332 (95.1) | 388 791 (74.4) |

| 100 mg | 32 713 (17.7) | 9688 (5.9) | 2394 (2.5) | 1185 (1.5) | 45 980 (8.8) |

| 150 mg | 64 645 (35.1) | 16 499 (10.1) | 4097 (4.3) | 2688 (3.4) | 87 909 (16.8) |

| Medications prescribed 1–180 days prior to aspirin prescription, no (%) | |||||

| PPI | 13 559 (7.4) | 17 674 (10.8) | 14 533 (15.1) | 13 720 (17.3) | 59 486 (11.4) |

| NSAID | 35 816 (19.4) | 34 889 (21.4) | 17 985 (18.7) | 12 087 (15.3) | 100 777 (19.3) |

| Glucocorticoids | 9524 (5.2) | 7768 (4.8) | 4878 (5.1) | 4016 (5.1) | 26 186 (5.0) |

| Medications prescribed 1–180 days after aspirin prescription, no (%) | |||||

| PPI | 18 130 (9.8) | 23 392 (14.4) | 18 726 (19.5) | 17 900 (22.6) | 78 148 (15.0) |

| NSAID | 35 025 (19.0) | 31 478 (19.3) | 15 229 (15.8) | 9655 (12.2) | 91 387 (17.5) |

| Glucocorticoids | 9892 (5.4) | 7857 (4.8) | 5034 (5.2) | 4104 (5.2) | 26 887 (5.1) |

| . | 2000–04 . | 2005–09 . | 2010–14 . | 2015–20 . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, no (%) | 184 416 (35.3) | 162 907 (31.2) | 96 172 (18.4) | 79 185 (15.1) | 522 680 (100) |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 68.6 (59.5, 77.2) | 65.7 (58.0, 74.5) | 65.9 (57.4, 73.9) | 66.0 (57.0, 73.1) | 66.7 (58.3, 75.2) |

| Male sex, no (%) | 88 390 (47.9) | 81 103 (49.8) | 48 554 (50.5) | 43 105 (54.4) | 261 152 (50.0) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, no (%) | |||||

| Diabetes | 25 297 (13.7) | 25 943 (15.9) | 13 740 (14.3) | 10 937 (13.8) | 75 917 (14.5) |

| Hypertension | 64 973 (35.2) | 66 072 (40.6) | 39 551 (41.1) | 30 620 (38.7) | 201 216 (38.5) |

| Hyper-cholesterolemia | 26 739 (14.5) | 61 048 (37.5) | 41 844 (43.5) | 37 767 (47.7) | 167 398 (32.0) |

| COPD | 2498 (1.4) | 2825 (1.7) | 1992 (2.1) | 2026 (2.6) | 9341 (1.8) |

| ≥1 cardiovascular risk factor | 95 006 (51.5) | 106 022 (65.1) | 65 232 (67.8) | 54 427 (68.7) | 320 687 (61.4) |

| Bleeding risk factors, no (%) | |||||

| Prior bleeding event | 16 002 (8.7) | 16 926 (10.4) | 12 218 (12.7) | 11 474 (14.5) | 56 620 (10.8) |

| Recent bleeding event | 10 236 (5.6) | 8806 (5.4) | 5610 (5.8) | 4689 (5.9) | 29 341 (5.6) |

| Prior peptic ulcer | 8283 (4.5) | 7080 (4.3) | 4139 (4.3) | 2941 (3.7) | 22 443 (4.3) |

| Liver disease | 2498 (1.4) | 2825 (1.7) | 1992 (2.1) | 2026 (2.6) | 9341 (1.8) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4012 (2.2) | 3370 (2.1) | 2528 (2.6) | 2656 (3.4) | 12 566 (2.4) |

| ≥ 1 bleeding risk factor | 26 197 (14.2) | 25 739 (15.8) | 17 812 (18.5) | 16 407 (20.7) | 86 155 (16.5) |

| Aspirin dose, no (%) | |||||

| 75 mg | 87 058 (47.2) | 136 720 (83.9) | 89 681 (93.3) | 75 332 (95.1) | 388 791 (74.4) |

| 100 mg | 32 713 (17.7) | 9688 (5.9) | 2394 (2.5) | 1185 (1.5) | 45 980 (8.8) |

| 150 mg | 64 645 (35.1) | 16 499 (10.1) | 4097 (4.3) | 2688 (3.4) | 87 909 (16.8) |

| Medications prescribed 1–180 days prior to aspirin prescription, no (%) | |||||

| PPI | 13 559 (7.4) | 17 674 (10.8) | 14 533 (15.1) | 13 720 (17.3) | 59 486 (11.4) |

| NSAID | 35 816 (19.4) | 34 889 (21.4) | 17 985 (18.7) | 12 087 (15.3) | 100 777 (19.3) |

| Glucocorticoids | 9524 (5.2) | 7768 (4.8) | 4878 (5.1) | 4016 (5.1) | 26 186 (5.0) |

| Medications prescribed 1–180 days after aspirin prescription, no (%) | |||||

| PPI | 18 130 (9.8) | 23 392 (14.4) | 18 726 (19.5) | 17 900 (22.6) | 78 148 (15.0) |

| NSAID | 35 025 (19.0) | 31 478 (19.3) | 15 229 (15.8) | 9655 (12.2) | 91 387 (17.5) |

| Glucocorticoids | 9892 (5.4) | 7857 (4.8) | 5034 (5.2) | 4104 (5.2) | 26 887 (5.1) |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; IQR, interquartile range, NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

| . | 2000–04 . | 2005–09 . | 2010–14 . | 2015–20 . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, no (%) | 184 416 (35.3) | 162 907 (31.2) | 96 172 (18.4) | 79 185 (15.1) | 522 680 (100) |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 68.6 (59.5, 77.2) | 65.7 (58.0, 74.5) | 65.9 (57.4, 73.9) | 66.0 (57.0, 73.1) | 66.7 (58.3, 75.2) |

| Male sex, no (%) | 88 390 (47.9) | 81 103 (49.8) | 48 554 (50.5) | 43 105 (54.4) | 261 152 (50.0) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, no (%) | |||||

| Diabetes | 25 297 (13.7) | 25 943 (15.9) | 13 740 (14.3) | 10 937 (13.8) | 75 917 (14.5) |

| Hypertension | 64 973 (35.2) | 66 072 (40.6) | 39 551 (41.1) | 30 620 (38.7) | 201 216 (38.5) |

| Hyper-cholesterolemia | 26 739 (14.5) | 61 048 (37.5) | 41 844 (43.5) | 37 767 (47.7) | 167 398 (32.0) |

| COPD | 2498 (1.4) | 2825 (1.7) | 1992 (2.1) | 2026 (2.6) | 9341 (1.8) |

| ≥1 cardiovascular risk factor | 95 006 (51.5) | 106 022 (65.1) | 65 232 (67.8) | 54 427 (68.7) | 320 687 (61.4) |

| Bleeding risk factors, no (%) | |||||

| Prior bleeding event | 16 002 (8.7) | 16 926 (10.4) | 12 218 (12.7) | 11 474 (14.5) | 56 620 (10.8) |

| Recent bleeding event | 10 236 (5.6) | 8806 (5.4) | 5610 (5.8) | 4689 (5.9) | 29 341 (5.6) |

| Prior peptic ulcer | 8283 (4.5) | 7080 (4.3) | 4139 (4.3) | 2941 (3.7) | 22 443 (4.3) |

| Liver disease | 2498 (1.4) | 2825 (1.7) | 1992 (2.1) | 2026 (2.6) | 9341 (1.8) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4012 (2.2) | 3370 (2.1) | 2528 (2.6) | 2656 (3.4) | 12 566 (2.4) |

| ≥ 1 bleeding risk factor | 26 197 (14.2) | 25 739 (15.8) | 17 812 (18.5) | 16 407 (20.7) | 86 155 (16.5) |

| Aspirin dose, no (%) | |||||

| 75 mg | 87 058 (47.2) | 136 720 (83.9) | 89 681 (93.3) | 75 332 (95.1) | 388 791 (74.4) |

| 100 mg | 32 713 (17.7) | 9688 (5.9) | 2394 (2.5) | 1185 (1.5) | 45 980 (8.8) |

| 150 mg | 64 645 (35.1) | 16 499 (10.1) | 4097 (4.3) | 2688 (3.4) | 87 909 (16.8) |

| Medications prescribed 1–180 days prior to aspirin prescription, no (%) | |||||

| PPI | 13 559 (7.4) | 17 674 (10.8) | 14 533 (15.1) | 13 720 (17.3) | 59 486 (11.4) |

| NSAID | 35 816 (19.4) | 34 889 (21.4) | 17 985 (18.7) | 12 087 (15.3) | 100 777 (19.3) |

| Glucocorticoids | 9524 (5.2) | 7768 (4.8) | 4878 (5.1) | 4016 (5.1) | 26 186 (5.0) |

| Medications prescribed 1–180 days after aspirin prescription, no (%) | |||||

| PPI | 18 130 (9.8) | 23 392 (14.4) | 18 726 (19.5) | 17 900 (22.6) | 78 148 (15.0) |

| NSAID | 35 025 (19.0) | 31 478 (19.3) | 15 229 (15.8) | 9655 (12.2) | 91 387 (17.5) |

| Glucocorticoids | 9892 (5.4) | 7857 (4.8) | 5034 (5.2) | 4104 (5.2) | 26 887 (5.1) |

| . | 2000–04 . | 2005–09 . | 2010–14 . | 2015–20 . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, no (%) | 184 416 (35.3) | 162 907 (31.2) | 96 172 (18.4) | 79 185 (15.1) | 522 680 (100) |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 68.6 (59.5, 77.2) | 65.7 (58.0, 74.5) | 65.9 (57.4, 73.9) | 66.0 (57.0, 73.1) | 66.7 (58.3, 75.2) |

| Male sex, no (%) | 88 390 (47.9) | 81 103 (49.8) | 48 554 (50.5) | 43 105 (54.4) | 261 152 (50.0) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, no (%) | |||||

| Diabetes | 25 297 (13.7) | 25 943 (15.9) | 13 740 (14.3) | 10 937 (13.8) | 75 917 (14.5) |

| Hypertension | 64 973 (35.2) | 66 072 (40.6) | 39 551 (41.1) | 30 620 (38.7) | 201 216 (38.5) |

| Hyper-cholesterolemia | 26 739 (14.5) | 61 048 (37.5) | 41 844 (43.5) | 37 767 (47.7) | 167 398 (32.0) |

| COPD | 2498 (1.4) | 2825 (1.7) | 1992 (2.1) | 2026 (2.6) | 9341 (1.8) |

| ≥1 cardiovascular risk factor | 95 006 (51.5) | 106 022 (65.1) | 65 232 (67.8) | 54 427 (68.7) | 320 687 (61.4) |

| Bleeding risk factors, no (%) | |||||

| Prior bleeding event | 16 002 (8.7) | 16 926 (10.4) | 12 218 (12.7) | 11 474 (14.5) | 56 620 (10.8) |

| Recent bleeding event | 10 236 (5.6) | 8806 (5.4) | 5610 (5.8) | 4689 (5.9) | 29 341 (5.6) |

| Prior peptic ulcer | 8283 (4.5) | 7080 (4.3) | 4139 (4.3) | 2941 (3.7) | 22 443 (4.3) |

| Liver disease | 2498 (1.4) | 2825 (1.7) | 1992 (2.1) | 2026 (2.6) | 9341 (1.8) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4012 (2.2) | 3370 (2.1) | 2528 (2.6) | 2656 (3.4) | 12 566 (2.4) |

| ≥ 1 bleeding risk factor | 26 197 (14.2) | 25 739 (15.8) | 17 812 (18.5) | 16 407 (20.7) | 86 155 (16.5) |

| Aspirin dose, no (%) | |||||

| 75 mg | 87 058 (47.2) | 136 720 (83.9) | 89 681 (93.3) | 75 332 (95.1) | 388 791 (74.4) |

| 100 mg | 32 713 (17.7) | 9688 (5.9) | 2394 (2.5) | 1185 (1.5) | 45 980 (8.8) |

| 150 mg | 64 645 (35.1) | 16 499 (10.1) | 4097 (4.3) | 2688 (3.4) | 87 909 (16.8) |

| Medications prescribed 1–180 days prior to aspirin prescription, no (%) | |||||

| PPI | 13 559 (7.4) | 17 674 (10.8) | 14 533 (15.1) | 13 720 (17.3) | 59 486 (11.4) |

| NSAID | 35 816 (19.4) | 34 889 (21.4) | 17 985 (18.7) | 12 087 (15.3) | 100 777 (19.3) |

| Glucocorticoids | 9524 (5.2) | 7768 (4.8) | 4878 (5.1) | 4016 (5.1) | 26 186 (5.0) |

| Medications prescribed 1–180 days after aspirin prescription, no (%) | |||||

| PPI | 18 130 (9.8) | 23 392 (14.4) | 18 726 (19.5) | 17 900 (22.6) | 78 148 (15.0) |

| NSAID | 35 025 (19.0) | 31 478 (19.3) | 15 229 (15.8) | 9655 (12.2) | 91 387 (17.5) |

| Glucocorticoids | 9892 (5.4) | 7857 (4.8) | 5034 (5.2) | 4104 (5.2) | 26 887 (5.1) |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; IQR, interquartile range, NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Characteristics of incident primary prevention aspirin users with and without diabetes

| . | 2000–04 . | 2005–09 . | 2010–14 . | 2015–20 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | No diabetes . | Diabetes . | No diabetes . | Diabetes . | No diabetes . | Diabetes . | No diabetes . | Diabetes . |

| Patients, no | 159 119 | 25 297 | 136 964 | 25 943 | 82 432 | 13 740 | 68 248 | 10 937 |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 69.3 (60.2, 77.8) | 64.1 (56.4, 70.5) | 66.3 (58.5, 75.2) | 62.7 (55.4, 70.5) | 66.2 (57.7, 74.3) | 64.2 (55.7, 71.5) | 66.1 (57.2, 73.3) | 64.7 (56.4, 72.1) |

| Male sex, no (%) | 74 282 (46.7) | 14 108 (55.8) | 66 185 (48.3) | 14 918 (57.5) | 40 666 (49.3) | 7888 (57.4) | 36 351 (53.3) | 6754 (61.8) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, no (%) | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 52 789 (33.2) | 12 184 (48.2) | 52 292 (38.2) | 13 780 (53.1) | 31 583 (38.3) | 7968 (58.0) | 24 072 (35.3) | 6548 (59.9) |

| Hyper-cholesterolemia | 19 233 (12.1) | 7506 (29.7) | 44 193 (32.3) | 16 855 (65.0) | 32 251 (39.1) | 9593 (69.8) | 30 036 (44.0) | 7731 (70.7) |

| COPD | 10 380 (6.5) | 1490 (5.9) | 9155 (6.7) | 1585 (6.1) | 6424 (7.8) | 1082 (7.9) | 5460 (8.0) | 959 (8.8) |

| ≥1 cardiovascular risk factora | 69 709 (43.8) | 16 201 (64.0) | 80 079 (58.5) | 21 554 (83.1) | 51 492 (62.5) | 11 945 (86.9) | 43 490 (63.7) | 9543 (87.3) |

| Bleeding risk factors, no (%) | ||||||||

| Prior bleeding event | 13 594 (8.5) | 2408 (9.5) | 14 075 (10.3) | 2851 (11.0) | 10 323 (12.5) | 1895 (13.8) | 9786 (14.3) | 1688 (15.4) |

| Recent bleeding event | 8701 (5.5) | 1535 (6.1) | 7376 (5.4) | 1430 (5.5) | 4790 (5.8) | 820 (6.0) | 4027 (5.9) | 662 (6.1) |

| Prior peptic ulcer | 7178 (4.5) | 1105 (4.4) | 5879 (4.3) | 1201 (4.6) | 3531 (4.3) | 608 (4.4) | 2491 (3.6) | 450 (4.1) |

| Liver disease | 1804 (1.1) | 694 (2.7) | 2008 (1.5) | 817 (3.1) | 1487 (1.8) | 505 (3.7) | 1586 (2.3) | 440 (4.0) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1870 (1.2) | 2142 (8.5) | 1803 (1.3) | 1567 (6.0) | 1575 (1.9) | 953 (6.9) | 1661 (2.4) | 995 (9.1) |

| ≥ 1 bleeding risk factor | 20 894 (13.1) | 5303 (21.0) | 20 435 (14,9) | 5304 (20.4) | 14 572 (17.7) | 3240 (23.6) | 13 450 (19.7) | 2957 (27.0) |

| . | 2000–04 . | 2005–09 . | 2010–14 . | 2015–20 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | No diabetes . | Diabetes . | No diabetes . | Diabetes . | No diabetes . | Diabetes . | No diabetes . | Diabetes . |

| Patients, no | 159 119 | 25 297 | 136 964 | 25 943 | 82 432 | 13 740 | 68 248 | 10 937 |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 69.3 (60.2, 77.8) | 64.1 (56.4, 70.5) | 66.3 (58.5, 75.2) | 62.7 (55.4, 70.5) | 66.2 (57.7, 74.3) | 64.2 (55.7, 71.5) | 66.1 (57.2, 73.3) | 64.7 (56.4, 72.1) |

| Male sex, no (%) | 74 282 (46.7) | 14 108 (55.8) | 66 185 (48.3) | 14 918 (57.5) | 40 666 (49.3) | 7888 (57.4) | 36 351 (53.3) | 6754 (61.8) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, no (%) | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 52 789 (33.2) | 12 184 (48.2) | 52 292 (38.2) | 13 780 (53.1) | 31 583 (38.3) | 7968 (58.0) | 24 072 (35.3) | 6548 (59.9) |

| Hyper-cholesterolemia | 19 233 (12.1) | 7506 (29.7) | 44 193 (32.3) | 16 855 (65.0) | 32 251 (39.1) | 9593 (69.8) | 30 036 (44.0) | 7731 (70.7) |

| COPD | 10 380 (6.5) | 1490 (5.9) | 9155 (6.7) | 1585 (6.1) | 6424 (7.8) | 1082 (7.9) | 5460 (8.0) | 959 (8.8) |

| ≥1 cardiovascular risk factora | 69 709 (43.8) | 16 201 (64.0) | 80 079 (58.5) | 21 554 (83.1) | 51 492 (62.5) | 11 945 (86.9) | 43 490 (63.7) | 9543 (87.3) |

| Bleeding risk factors, no (%) | ||||||||

| Prior bleeding event | 13 594 (8.5) | 2408 (9.5) | 14 075 (10.3) | 2851 (11.0) | 10 323 (12.5) | 1895 (13.8) | 9786 (14.3) | 1688 (15.4) |

| Recent bleeding event | 8701 (5.5) | 1535 (6.1) | 7376 (5.4) | 1430 (5.5) | 4790 (5.8) | 820 (6.0) | 4027 (5.9) | 662 (6.1) |

| Prior peptic ulcer | 7178 (4.5) | 1105 (4.4) | 5879 (4.3) | 1201 (4.6) | 3531 (4.3) | 608 (4.4) | 2491 (3.6) | 450 (4.1) |

| Liver disease | 1804 (1.1) | 694 (2.7) | 2008 (1.5) | 817 (3.1) | 1487 (1.8) | 505 (3.7) | 1586 (2.3) | 440 (4.0) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1870 (1.2) | 2142 (8.5) | 1803 (1.3) | 1567 (6.0) | 1575 (1.9) | 953 (6.9) | 1661 (2.4) | 995 (9.1) |

| ≥ 1 bleeding risk factor | 20 894 (13.1) | 5303 (21.0) | 20 435 (14,9) | 5304 (20.4) | 14 572 (17.7) | 3240 (23.6) | 13 450 (19.7) | 2957 (27.0) |

In addition to diabetes.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; IQR, interquartile range.

Characteristics of incident primary prevention aspirin users with and without diabetes

| . | 2000–04 . | 2005–09 . | 2010–14 . | 2015–20 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | No diabetes . | Diabetes . | No diabetes . | Diabetes . | No diabetes . | Diabetes . | No diabetes . | Diabetes . |

| Patients, no | 159 119 | 25 297 | 136 964 | 25 943 | 82 432 | 13 740 | 68 248 | 10 937 |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 69.3 (60.2, 77.8) | 64.1 (56.4, 70.5) | 66.3 (58.5, 75.2) | 62.7 (55.4, 70.5) | 66.2 (57.7, 74.3) | 64.2 (55.7, 71.5) | 66.1 (57.2, 73.3) | 64.7 (56.4, 72.1) |

| Male sex, no (%) | 74 282 (46.7) | 14 108 (55.8) | 66 185 (48.3) | 14 918 (57.5) | 40 666 (49.3) | 7888 (57.4) | 36 351 (53.3) | 6754 (61.8) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, no (%) | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 52 789 (33.2) | 12 184 (48.2) | 52 292 (38.2) | 13 780 (53.1) | 31 583 (38.3) | 7968 (58.0) | 24 072 (35.3) | 6548 (59.9) |

| Hyper-cholesterolemia | 19 233 (12.1) | 7506 (29.7) | 44 193 (32.3) | 16 855 (65.0) | 32 251 (39.1) | 9593 (69.8) | 30 036 (44.0) | 7731 (70.7) |

| COPD | 10 380 (6.5) | 1490 (5.9) | 9155 (6.7) | 1585 (6.1) | 6424 (7.8) | 1082 (7.9) | 5460 (8.0) | 959 (8.8) |

| ≥1 cardiovascular risk factora | 69 709 (43.8) | 16 201 (64.0) | 80 079 (58.5) | 21 554 (83.1) | 51 492 (62.5) | 11 945 (86.9) | 43 490 (63.7) | 9543 (87.3) |

| Bleeding risk factors, no (%) | ||||||||

| Prior bleeding event | 13 594 (8.5) | 2408 (9.5) | 14 075 (10.3) | 2851 (11.0) | 10 323 (12.5) | 1895 (13.8) | 9786 (14.3) | 1688 (15.4) |

| Recent bleeding event | 8701 (5.5) | 1535 (6.1) | 7376 (5.4) | 1430 (5.5) | 4790 (5.8) | 820 (6.0) | 4027 (5.9) | 662 (6.1) |

| Prior peptic ulcer | 7178 (4.5) | 1105 (4.4) | 5879 (4.3) | 1201 (4.6) | 3531 (4.3) | 608 (4.4) | 2491 (3.6) | 450 (4.1) |

| Liver disease | 1804 (1.1) | 694 (2.7) | 2008 (1.5) | 817 (3.1) | 1487 (1.8) | 505 (3.7) | 1586 (2.3) | 440 (4.0) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1870 (1.2) | 2142 (8.5) | 1803 (1.3) | 1567 (6.0) | 1575 (1.9) | 953 (6.9) | 1661 (2.4) | 995 (9.1) |

| ≥ 1 bleeding risk factor | 20 894 (13.1) | 5303 (21.0) | 20 435 (14,9) | 5304 (20.4) | 14 572 (17.7) | 3240 (23.6) | 13 450 (19.7) | 2957 (27.0) |

| . | 2000–04 . | 2005–09 . | 2010–14 . | 2015–20 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | No diabetes . | Diabetes . | No diabetes . | Diabetes . | No diabetes . | Diabetes . | No diabetes . | Diabetes . |

| Patients, no | 159 119 | 25 297 | 136 964 | 25 943 | 82 432 | 13 740 | 68 248 | 10 937 |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 69.3 (60.2, 77.8) | 64.1 (56.4, 70.5) | 66.3 (58.5, 75.2) | 62.7 (55.4, 70.5) | 66.2 (57.7, 74.3) | 64.2 (55.7, 71.5) | 66.1 (57.2, 73.3) | 64.7 (56.4, 72.1) |

| Male sex, no (%) | 74 282 (46.7) | 14 108 (55.8) | 66 185 (48.3) | 14 918 (57.5) | 40 666 (49.3) | 7888 (57.4) | 36 351 (53.3) | 6754 (61.8) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, no (%) | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 52 789 (33.2) | 12 184 (48.2) | 52 292 (38.2) | 13 780 (53.1) | 31 583 (38.3) | 7968 (58.0) | 24 072 (35.3) | 6548 (59.9) |

| Hyper-cholesterolemia | 19 233 (12.1) | 7506 (29.7) | 44 193 (32.3) | 16 855 (65.0) | 32 251 (39.1) | 9593 (69.8) | 30 036 (44.0) | 7731 (70.7) |

| COPD | 10 380 (6.5) | 1490 (5.9) | 9155 (6.7) | 1585 (6.1) | 6424 (7.8) | 1082 (7.9) | 5460 (8.0) | 959 (8.8) |

| ≥1 cardiovascular risk factora | 69 709 (43.8) | 16 201 (64.0) | 80 079 (58.5) | 21 554 (83.1) | 51 492 (62.5) | 11 945 (86.9) | 43 490 (63.7) | 9543 (87.3) |

| Bleeding risk factors, no (%) | ||||||||

| Prior bleeding event | 13 594 (8.5) | 2408 (9.5) | 14 075 (10.3) | 2851 (11.0) | 10 323 (12.5) | 1895 (13.8) | 9786 (14.3) | 1688 (15.4) |

| Recent bleeding event | 8701 (5.5) | 1535 (6.1) | 7376 (5.4) | 1430 (5.5) | 4790 (5.8) | 820 (6.0) | 4027 (5.9) | 662 (6.1) |

| Prior peptic ulcer | 7178 (4.5) | 1105 (4.4) | 5879 (4.3) | 1201 (4.6) | 3531 (4.3) | 608 (4.4) | 2491 (3.6) | 450 (4.1) |

| Liver disease | 1804 (1.1) | 694 (2.7) | 2008 (1.5) | 817 (3.1) | 1487 (1.8) | 505 (3.7) | 1586 (2.3) | 440 (4.0) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1870 (1.2) | 2142 (8.5) | 1803 (1.3) | 1567 (6.0) | 1575 (1.9) | 953 (6.9) | 1661 (2.4) | 995 (9.1) |

| ≥ 1 bleeding risk factor | 20 894 (13.1) | 5303 (21.0) | 20 435 (14,9) | 5304 (20.4) | 14 572 (17.7) | 3240 (23.6) | 13 450 (19.7) | 2957 (27.0) |

In addition to diabetes.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; IQR, interquartile range.

Incident aspirin users with diabetes had a greater burden of comorbidities compared with incident users without diabetes as well as the at-risk diabetes population (Table 2 and Supplementary material online, Table S2).

When evaluating concomitant temporal trends of medications that may affect bleeding risk, we found that the percentage of patients redeeming a prescription for PPI both before and after aspirin redemption increased, whereas the use of NSAID decreased (Table 1).

A total of 16 217 (3.1%) persons started aspirin therapy in temporal relation to a CCTA. The results were similar with exclusion of this subgroup (see Supplementary material online, Table S3).

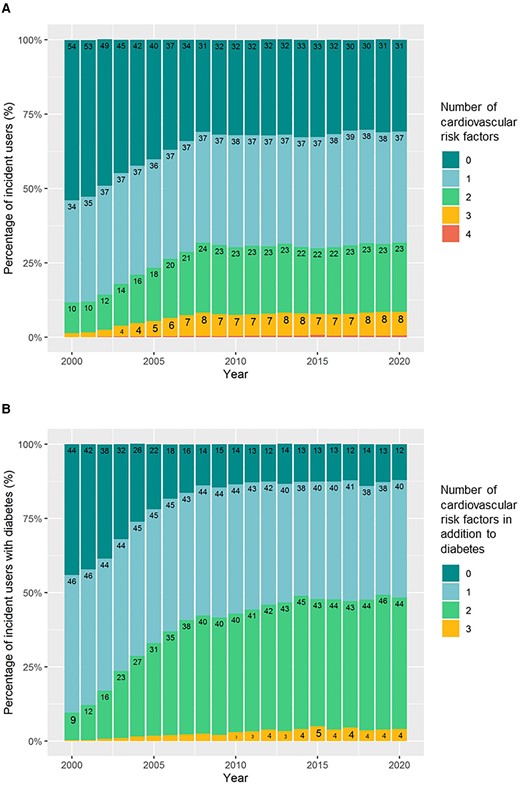

Number of cardiovascular risk factors in incident users

The percentage of incident aspirin users with no CV risk factors (diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or COPD) decreased from 53.8% in 2000 to 35.1% in 2020 (Figure 3A). Incident users with one, two, three, and four risk factors, respectively, increased over time. Among individuals with diabetes, the proportion with no other risk factors decreased from 44.1% in 2000 to 12.1% in 2020 (Figure 3B).

Number of cardiovascular risk factors in incident aspirin users in (A): the overall population of incident users and (B): incident users with diabetes. The figures show the percentage of incident users with 0–4 risk factors for cardiovascular disease present at the time of aspirin redemption. Cardiovascular risk factors were defined as diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (a proxy for smoking).

Temporal trends in prevalent aspirin users

The temporal trends in prevalent aspirin users followed a unimodal curve (Figure 4). The overall prevalence peaked at 7.7% in 2008 decreasing to 3.3% in 2020. The prevalence among at-risk individuals with diabetes peaked in 2009 at 38.5% and was the lowest at 17.1% in 2020. The percentage of prevalent aspirin users with diabetes increased throughout the study period and was 29% in 2020 (see Supplementary material online, Figure S7).

Temporal trends in prevalent users of aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. The figure shows the proportion of at-risk individuals prescribed aspirin in total (grey circles) and stratified by presence of diabetes (diabetes: green triangles, no diabetes: blue rhombuses) on an annual basis from 2000 through 2020. Temporal markers of the European Society of Cardiology guidelines on aspirin in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease are presented. CVD, cardiovascular disease; ESC, European Society of Cardiology.

Discussion

This nationwide registry-based cohort study examined the temporal trends and characteristics of aspirin users with and without diabetes in the primary preventive setting from 2000 through 2020. We found that aspirin use decreased with a similar trend in individuals with and without diabetes. However, the drug remained in prevalent use for primary prevention in a substantial proportion of individuals with and without diabetes and a large proportion of individuals started aspirin therapy in the absence of traditional CV risk factors.

Guideline recommendations for aspirin in primary prevention have changed throughout the past decades, and global discrepancies remain.26 In 2007, the ESC CVD prevention guidelines stated that aspirin could be considered in primary prevention of CVD if the 10-year risk of CV mortality was increased and blood pressure controlled.6 On the contrary, the 2007 ESC guidelines for patients with diabetes did not mention aspirin for the primary prevention of CVD, whereas the drug was recommended for prevention of stroke with a Class I recommendation.27 These 2007 guidelines appear to be reflected in our results as the steepest decline in incident users was seen in 2008–14, and the peak in prevalent users likewise was observed in 2008. In 2016, the ESC CVD prevention guidelines recommended against aspirin for primary prevention of CVD (Class III). This recommendation was modified, when the 2019 and 2021 ESC CVD prevention guidelines stated that aspirin may be considered in individuals with diabetes at high CV risk and low risk of bleeding (Class IIb).15,28 In the recent American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and the US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, aspirin can be considered in middle-aged individuals at high risk of CVD (Class IIb and Grade C, respectively).16,18 Several previous studies have reported misuse with respect to guideline recommendations.20–22,29–32 Our data suggest that even though there was a decline in users of aspirin, overutilization and inappropriate prescriptions still occur. A recent US registry-based study of 855 366 individuals in 2018–19 reported inappropriate aspirin prescriptions in 26–28% of aspirin users.22 Another US study investigating trends in aspirin use in 45 323 adults without CVD aged ≥40 years in 1998–2019 found, similar to our study, an increase in aspirin use until 2009 followed by a decreasing trend.21 The proportion of individuals treated with aspirin was higher compared with our study, as 27.5% of responders without CVD reported aspirin use in 2019. The divergence might be due to differing guidelines between the USA and Europe.33

Contemporary randomized clinical trials of aspirin for primary prevention in individuals at moderate CV risk,7 the elderly,8 and those with diabetes11 reported limited or no benefit of aspirin in preventing CVD, with a concomitant increase in bleeding. A recent Danish registry-based study also found a non-negligible risk of bleeding with primary preventive aspirin use, especially for individuals ≥80 years, in whom the incidence of major bleeding was 2.2 per 100 patient years in 2018.20 Contrary to our hypothesis, we observed an increasing percentage of incident aspirin users with high bleeding risk over the study period. The same pattern was found in non-aspirin users and likely reflects an increased focus on registration, improved quality of the Danish registries, and inclusion of all prior bleeding episodes. Also worth noting is that age is a key driver of CVD risk and bleeding risk, and so the use of CVD risk to identify persons for primary prevention of aspirin may also contribute to this observation. A higher proportion of incident users redeemed a prescription of PPIs after vs. before aspirin redemption. Furthermore, during the study period, the overall use of PPI increased, the use of NSAID decreased, and almost all incident users were started on 75 mg aspirin. This potentially reflects a greater attention to strategies that mitigate the bleeding risk of aspirin. However, our data nonetheless indicate that, among individuals at increased bleeding risk, more care may need to be taken to avoid aspirin prescription in the first place.

Aspirin has long been used as a primary preventive drug in subjects with diabetes due to increased platelet activation and abnormalities increasing the risk of CVD.34,35 Randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses in individuals with diabetes have given divergent results,9–11,36–38 and aspirin is now only recommended in those at high, but not low, CV risk.17,19 Compared with our findings, a higher prevalence of aspirin users was found in a US cross-sectional study using survey data reporting aspirin use for primary prevention. In total, 61.7% of older adults with diabetes reported aspirin use.32 However, this study was limited to individuals ≥60 years and included over the counter sale of aspirin.

We observed a temporal decline in incident aspirin users with diabetes over the period of observation, whereas an increasing percentage of prevalent users had a diagnosis of diabetes. These findings indicate that individuals with diabetes appear to be consistent users compared with individuals without diabetes. Subjects with diabetes who did start aspirin therapy also had an increasing burden of CV risk factors over time. This may indicate greater attention to starting aspirin in those at the highest risk of CVD.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the study include the large sample size and the use of nationwide Danish registries with high accuracy of diagnoses.39 Subjects included in the analyses were based on a source population consisting of all citizens in Denmark, representing a broad spectrum of unselected individuals. A limitation of our study is the lack of information on smoking, family history of CVD, and atherosclerotic plaques at the level of the carotid artery, which are likely to affect the prescription of aspirin in primary prevention. However, in Denmark, assessment of the carotid artery is rarely done without stroke or transient ischaemic attack as an indication, and we believe it is not likely to influence our data. The diagnosis of diabetes was based on either a registry-based diagnosis through the hospital (inpatient or outpatient) or redemption of a prescription for a glucose-lowering drug. Therefore, individuals treated with diet and lifestyle therapy alone may not have been included. We only included individuals ≥40 years, which may limit generalizability. This criterion was chosen as prescription of aspirin in younger persons is likely to be due to high risk based on information not available to us, e.g. strong family history.16,18 It is also possible that some of the primary prevention adults included in our study were prescribed aspirin despite a lack of CVD risk factors for the purpose of reducing colorectal cancer risk.40 Finally, over-the-counter sale of low-dose aspirin is not available in the Danish Registry of Medicinal Product Statistics and was not included in the analysis. However, medications are partially reimbursed in Denmark minimizing over the counter use, and we aimed at assessing the temporal trends in the prescription pattern of aspirin.

Perspectives

Results from our study bring the misuse of aspirin in primary prevention of CVD in individuals with and without diabetes into focus. The study underlines the need for minimizing implementation gaps after guideline changes, e.g. by focusing on improved guidance of general practitioners.

Conclusion

Prescription of aspirin for primary prevention of CVD has decreased over the last two decades in individuals both with and without diabetes, and more attention is given to mitigate the bleeding risk. However, aspirin appears to be inappropriately prescribed for primary prevention in many adults, given that a large proportion of incident users had no CV risk factors. Efforts to inform appropriate prescription of aspirin are needed, e.g. by improved guidance for general practitioners.

Supplementary data

The Supplementary Material is available online and consists of supplementary figures and tables as cited in the text.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Journal of Preventive Cardiology online.

Acknowledgements

None.

Authors’ contributions

A.M.D.K. conceptualized the hypothesis, designed the work, analysed and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. M.P., K.K., and E.P. conceptualized the hypothesis, designed the work, analysed and interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. C.T.P. and W.M.E. interpreted the data and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Data availability

The legislation of Statistics Denmark does not allow data sharing, but access can be granted with proper permission.

References

Author notes

Conflict of interest: M.P. discloses the following relationships not related to the content of the manuscript—Advisory Board: AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag; Grant Support: Danish Cardiovascular Academy funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation and the Danish Heart Foundation (grant number: CPD5Y-2022004-HF); Speaker Honorarium: AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen-Cilag.

Comments