-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Violeta González-Salvado, Carlos Peña-Gil, Óscar Lado-Baleato, Carmen Cadarso-Suárez, Guillermo Prada-Ramallal, Eva Prescott, Matthias Wilhelm, Prisca Eser, Marie-Christine Iliou, Uwe Zeymer, Diego Ardissino, Wendy Bruins, Astrid E van der Velde, Arnoud W J Van’t Hof, Ed P de Kluiver, Evelien K Kolkman, Leonie Prins, José Ramón González Juanatey, Offering, participation and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programmes in the elderly: a European comparison based on the EU-CaRE multicentre observational study, European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, Volume 28, Issue 5, May 2021, Pages 558–568, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwaa104

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is strongly recommended but participation of elderly patients has not been well characterized. This study aims to analyse current rates and determinants of CR referral, participation, adherence, and compliance in a contemporary European cohort of elderly patients.

The EU-CaRE observational study included data from consecutive patients aged ≥ 65 with acute coronary syndrome, revascularization, stable coronary artery disease, or heart valve replacement, recruited in eight European centres. Rates and factors determining offering, participation, and adherence to CR programmes and compliance with training sessions were studied across centres, under consideration of extensive-outpatient vs. intensive-inpatient programmes. Three thousand, four hundred, and seventy-one patients were included in the offering and participation analysis. Cardiac rehabilitation was offered to 80.8% of eligible patients, formal contraindications being the main reason for not offering CR. Mean participation was 68.0%, with perceived lack of usefulness and transport issues being principal barriers. Mean adherence to CR programmes of participants in the EU-CaRE study (n = 1663) was 90.3%, with hospitalization/physical impairment as principal causes of dropout. Mean compliance with training sessions was 86.1%. Older age was related to lower offering and participation, and comorbidity was associated with lower offering, participation, adherence, and compliance. Intensive-inpatient programmes displayed higher adherence (97.1% vs. 85.9%, P < 0.001) and compliance (full compliance: 66.0% vs. 38.8%, P < 0.001) than extensive-outpatient programmes.

In this European cohort of elderly patients, older age and comorbidity tackled patients’ referral and uptake of CR programmes. Intensive-inpatient CR programmes showed higher completion than extensive-outpatient CR programmes, suggesting this formula could suit some elderly patients.

Introduction

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) aims to lessen the adverse outcomes of cardiovascular disease, ameliorate symptoms, enhance quality of life, and improve prognosis, reducing the risk of future events and mortality. Modern CR programmes perform a multifaceted intervention including cardiovascular risk evaluation and management, counselling for physical activity, psychosocial support, adherence to medical therapies, and patient and family education.1,2

The benefits of exercise-based CR programmes for patients with coronary artery disease,3,4 heart failure,5 or after heart valve intervention6 have been well documented, as well as their cost-effectiveness.7 Although CR constitutes an essential part of the comprehensive management of Cardiology patients,8 these programmes remain underutilized, with global participation rates that have remained below 50% for decades.9

The ageing of the population and advances in treatments have led to higher survival and the progressive chronification of cardiovascular disease, and to a higher proportion of elderly patients now being treated in Cardiology departments. However, despite the evidence supporting the benefits of CR for elderly patients,10–13 this group is less likely to take part in conventional programmes.14–16

The type of intervention performed within CR programmes in Europe differs across centres and countries, with inpatient and outpatient programmes, shorter, intensive modalities and longer, extensive programmes. However, these services have not been specifically designed for an ageing population, more prone to frailty and comorbidity, and with specific characteristics—such as transport issues—that should be considered, also in the setting of CR.17 It is unknown which CR modality attracts the highest participation among elderly patients. Moreover, factors affecting elderly patients’ adherence to CR programmes have not been well characterized. This study aims to provide an updated portrait of rates and factors influencing CR offering and participation, as well as adherence and compliance with programmes, in a contemporary cohort of elderly patients (≥65 years) from eight European centres participating in the EU-CaRE project.

Methods

Study design and population

This research includes data from the prospective, multi-centre, observational EU-CaRE study, conducted between September 2015 and January 2018. It was conceived to provide a snapshot of the existing CR programmes among the elderly, across eight participating centres in eight European countries [Bern (CH), Copenhagen (DK), Ludwigshafen (D), Paris (F), Parma (I), Nijmegen (NL), Santiago de Compostela (E), and Zwolle (NL)). It included all patients aged ≥65 years with recent acute coronary syndrome (ACS), coronary revascularization—including percutaneous (PCI) or bypass grafting (CABG)—documented coronary artery disease without revascularization, or surgical or percutaneous treatment for valve disease, who were offered CR as part of a standard of care at each centre.18

All eligible patients who were offered and accepted CR were identified as ‘participants’ and those who refused CR as ‘non-participants’, independently of their willingness to join the study. This was purposely designed to allow studying barriers to participation in CR itself. In order to ensure a certain degree of homogeneity in the recruitment of the sample, only the subset of patients who suffered ACS or underwent revascularization (PCI/CABG) were considered in the offering and participation analysis, as established in the EU-CaRE Statistical Analysis Plan.

Participants who consented to take part in the observational EU-CaRE study, constituted the ‘EU-CaRE sample’. Adherence to CR programmes and compliance with training sessions were studied on the global observational EU-CaRE sample (including ACS/PCI/CABG patients plus those with non-revascularized coronary artery disease, or heart valve intervention, n = 1633). Patients who abandoned the CR programme before its onset (‘early dropouts’) were distinguished from those leaving the programme once initiated (‘late dropouts’). Follow-up was set in 12 months.

Data collection and definitions

Collected data included programme details, baseline patient characteristics, offering, and participation rates, reasons for not offering and for not participating, number of dropouts with reasons, and number of training sessions attended. Two modalities of CR programmes were differentiated according to their duration and frequency of training sessions, using an arbitrary definition: intensive programmes (<4 weeks and >3 sessions/week) and extensive programmes (≥4 weeks and ≤3 training sessions/week).

CR-offering rate was defined as the proportion of patients who were offered CR out of the total number of screened ACS/PCI/CABG patients; participation rate was defined as the proportion of patients who accepted participation out of those who were offered the programme. Adherence was defined as the proportion of EU-CaRE participants who completed the programme (absence of dropout), while compliance was defined by the number of training sessions attended per CR programme in relation to the number of sessions planned. These variables were defined as established in the EU-CaRE statistical plan.

Sociodemographic factors, index event type, cardiovascular risk characteristics, and comorbidities were compared between offered vs. non-offered patients, and between participants vs. non-participants. Also, predictive models of participation were developed for outpatient programmes with sufficient number of participants and non-participants (Zwolle, Copenhagen, Bern, and Santiago). Additionally, cardiovascular symptoms (i.e. dyspnoea, angina), distance to the centre, laboratory parameters, and adverse events were also explored in the adherence and compliance analysis.

Statistical analysis

For the descriptive analysis, continuous variables were expressed as median with interquartile range (Q3–Q1), and discrete/nominal variables were defined by their absolute value and percentage. Inter-centre and inter-group differences (i.e. offered vs. non-offered patients, participants vs. non-participants), and between types of programmes (intensive-inpatient vs. extensive-outpatient) were assessed by means of the Fisher’s exact test for discrete/nominal variables, and the Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis H test in the case of continuous variables, as appropriate.

To study participation, variables, such as age, gender, cardiovascular risk factors, and comorbidities, were considered as potential predictors (yes/no). Predictive logistic regression models for participation were constructed using Generalized Additive Models (GAM).19 These flexible models allowed estimating smooth effects of the continuous covariates (such as age) on the binary response (participation vs. non-participation) in each outpatient centre separately. The predictive capacity of each fitted model was appraised by means of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the corresponding area under the curve (AUC), along with its 95% confidence interval (CI). The selection of predictor variables of participation was conducted using AUC criteria, considering the combination of variables that led to the best predictive capacity. The goodness of fit for each model was tested using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test.

To study compliance, a beta regression model was fitted using GAM regression for location, scale, and shape (GAMLSS).20 The selection of predictive variables was done using the Generalized Akaike’s Information Criterion (GAIC). The effects of the explanatory variables on the response were expressed in terms of odds ratios (ORs) together with their corresponding 95% CI. P-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

All statistical analyses were carried out using the free statistical software R (R core team 2016), using the mgcv package,23 for fitting GAMS, gamlss package for fitting GAMLSS regression models, and pROC24 to conduct the ROC analysis.

Results

Programmes’ characteristics

There was great heterogeneity across centres, concerning types of CR programmes, screening timing (during or after admission: Phases I/II), and referral system. Outpatient programmes followed an extensive training modality (Bern, Copenhagen, Nijmegen, Santiago, and Zwolle, 1–3 sessions/week), while inpatient programmes generally followed an intensive modality (Ludwigshafen, Parma, and Paris, 5–9 sessions/week) (Table 1). In Nijmegen, Parma, and Ludwigshafen patients were mostly referred to directly join the CR programme, which affected referral and participation assessment in these centres. EU-CaRE participants’ baseline characteristics and index event varied across centres, as previously described.21

| . | Extensive CR programmes . | Intensive CR programmes . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copenhagen . | Bern . | Zwolle . | Santiago . | Nijmegen . | Parma . | Paris . | Ludwigshafen . | |

| Origin of patients | Outpatients | Outpatients | Outpatients | Outpatients | Outpatients | In and outpatients | In and outpatients | Outpatients |

| Patients’ screening (phase of CR) | After admission (Phase II) | During and after admission (Phase I/II) | After admission (Phase II) | During and after admission (Phase I/II) | After admission (Phase II) | After admission (Phase II) | During and after admission (Phase I/II) | During and after admission (Phase I/II) |

| Referral by others | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes (entirely) | Yes (entirely) | Yes | Yes (entirely) |

| Setting | Separate building | In hospital | Separate building | In hospital | Separate building | Separate building | Separate building | Separate building |

| Programme duration (weeks) | 12 | 18 | 6 | 8–12 | 6 | In: 2 Out: 8 | In: 3.5 Out: 3 | 3 |

| Number of training sessions offered | 16 | 36 | 10 | 24 | 12 | In: 18 Out: 24 | In: 17 Out: 15 | 15 |

| Training sessions per week | 2 | 2 | 1–2 | 2–3 | 2 | In: 9 Out: 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Follow-up contact (at 6–12 months) | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | In: Yes Out: No | In: Yes Out: Yes | Yes |

| Covered by health insurance | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| . | Extensive CR programmes . | Intensive CR programmes . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copenhagen . | Bern . | Zwolle . | Santiago . | Nijmegen . | Parma . | Paris . | Ludwigshafen . | |

| Origin of patients | Outpatients | Outpatients | Outpatients | Outpatients | Outpatients | In and outpatients | In and outpatients | Outpatients |

| Patients’ screening (phase of CR) | After admission (Phase II) | During and after admission (Phase I/II) | After admission (Phase II) | During and after admission (Phase I/II) | After admission (Phase II) | After admission (Phase II) | During and after admission (Phase I/II) | During and after admission (Phase I/II) |

| Referral by others | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes (entirely) | Yes (entirely) | Yes | Yes (entirely) |

| Setting | Separate building | In hospital | Separate building | In hospital | Separate building | Separate building | Separate building | Separate building |

| Programme duration (weeks) | 12 | 18 | 6 | 8–12 | 6 | In: 2 Out: 8 | In: 3.5 Out: 3 | 3 |

| Number of training sessions offered | 16 | 36 | 10 | 24 | 12 | In: 18 Out: 24 | In: 17 Out: 15 | 15 |

| Training sessions per week | 2 | 2 | 1–2 | 2–3 | 2 | In: 9 Out: 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Follow-up contact (at 6–12 months) | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | In: Yes Out: No | In: Yes Out: Yes | Yes |

| Covered by health insurance | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| . | Extensive CR programmes . | Intensive CR programmes . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copenhagen . | Bern . | Zwolle . | Santiago . | Nijmegen . | Parma . | Paris . | Ludwigshafen . | |

| Origin of patients | Outpatients | Outpatients | Outpatients | Outpatients | Outpatients | In and outpatients | In and outpatients | Outpatients |

| Patients’ screening (phase of CR) | After admission (Phase II) | During and after admission (Phase I/II) | After admission (Phase II) | During and after admission (Phase I/II) | After admission (Phase II) | After admission (Phase II) | During and after admission (Phase I/II) | During and after admission (Phase I/II) |

| Referral by others | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes (entirely) | Yes (entirely) | Yes | Yes (entirely) |

| Setting | Separate building | In hospital | Separate building | In hospital | Separate building | Separate building | Separate building | Separate building |

| Programme duration (weeks) | 12 | 18 | 6 | 8–12 | 6 | In: 2 Out: 8 | In: 3.5 Out: 3 | 3 |

| Number of training sessions offered | 16 | 36 | 10 | 24 | 12 | In: 18 Out: 24 | In: 17 Out: 15 | 15 |

| Training sessions per week | 2 | 2 | 1–2 | 2–3 | 2 | In: 9 Out: 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Follow-up contact (at 6–12 months) | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | In: Yes Out: No | In: Yes Out: Yes | Yes |

| Covered by health insurance | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| . | Extensive CR programmes . | Intensive CR programmes . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copenhagen . | Bern . | Zwolle . | Santiago . | Nijmegen . | Parma . | Paris . | Ludwigshafen . | |

| Origin of patients | Outpatients | Outpatients | Outpatients | Outpatients | Outpatients | In and outpatients | In and outpatients | Outpatients |

| Patients’ screening (phase of CR) | After admission (Phase II) | During and after admission (Phase I/II) | After admission (Phase II) | During and after admission (Phase I/II) | After admission (Phase II) | After admission (Phase II) | During and after admission (Phase I/II) | During and after admission (Phase I/II) |

| Referral by others | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes (entirely) | Yes (entirely) | Yes | Yes (entirely) |

| Setting | Separate building | In hospital | Separate building | In hospital | Separate building | Separate building | Separate building | Separate building |

| Programme duration (weeks) | 12 | 18 | 6 | 8–12 | 6 | In: 2 Out: 8 | In: 3.5 Out: 3 | 3 |

| Number of training sessions offered | 16 | 36 | 10 | 24 | 12 | In: 18 Out: 24 | In: 17 Out: 15 | 15 |

| Training sessions per week | 2 | 2 | 1–2 | 2–3 | 2 | In: 9 Out: 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Follow-up contact (at 6–12 months) | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | In: Yes Out: No | In: Yes Out: Yes | Yes |

| Covered by health insurance | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Offering of cardiac rehabilitation programmes

Out of 4174 patients screened, 3471 patients with ACS (53.7%), PCI (65.3%), or CABG (26.2%) were included in the offering analysis. CR was offered to >80% of eligible patients (73–100% in outpatient-extensive programs; 53–100% in inpatient-intensive programmes, P < 0.001) (Table 2). Main reasons for not offering outpatient CR were having a contraindication and living far from the centre.

Cardiac rehabilitation offering and participation and adherence and compliance by centre

| . | Extensive CR programmes . | Intensive CR programmes . | Total, n (%) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copenhagen . | Bern . | Zwolle . | Santiago . | Nijmegena . | Parmaa . | Paris . | Ludwigshafena . | ||

| Offering and participation (n = 3471, elderly ACS/PCI/CABG patients) | |||||||||

| Screened patients, n | 613 | 856 | 757 | 663 | 89 | 367 | 587 | 242 | 4174 |

| ACS/PCI/CABG patients, n (%) | 537 (87.60%) | 637 (74.42%) | 746 (98.55%) | 594 (89.59%) | 29 (32.58%) | 270 (73.57%) | 457 (77.85%) | 201 (83.06%) | 3471 (83.16%) |

| Patients offered CR, n (%) | 454 (84.54%) | 541 (84.92%) | 688 (92.22%) | 434 (73.06%) | 29 (100%) | 213 (78.89%) | 246 (53.83%) | 201 (100%) | 2806 (80.84%) |

| Patients accepting CR, n (%) | 308 (67.84%) | 336 (62.11%) | 406 (59.01%) | 201 (46.31%) | 28 (96.55%) | 198 (92.96%) | 230 (93.50%) | 201 (100%) | 1908 (68.00%) |

| Adherence and compliance (n = 1607, EU-CaRE sampleb) | |||||||||

| EU-CaRE sample, n | 237 | 203 | 220 | 247 | 32 | 247 | 219 | 228 | 1633 |

| Early dropouts, n (%) | 28/228 (12.28%) | 3/203 (1.48%) | 0/219 (0.00%) | 34/247 (13.77%) | 0/32 (0.00%) | 3/241 (1.25%) | 0/219 (0.00%) | 0/218 (0.00%) | 68/1607 (4.23%) |

| Late dropouts, n (%) | 10/228 (4.39%) | 24/203 (11.82%) | 10/219 (4.57%) | 27/247 (10.93%) | 0/32 (0.00%) | 10/241 (4.15%) | 5/219 (2.28%) | 2/218 (0.92%) | 88/1607 (5.48%) |

| Total dropouts, n (%) | 38/228 (16.67%) | 27/203 (13.30%) | 10/219 (4.57%) | 61/247 (24.70%) | 0/32 (0.00%) | 13/241 (5.39%) | 5/219 (2.28%) | 2/218 (0.92%) | 156/1607 (9.71%) |

| Compliance, % median (IQR) | 88% (62–100%) | 94% (76.5–100%) | 100% (90–100%) | 92% (67–100%) | 100% (90.3–100%) | 95% (85–100%) | 100% (92–100%) | 100% (100–100%) | 97% (86–100%) |

| Compliance, % mean (SD) | 73.08% (33.57 %) | 81.81% (27.08 %) | 93.63% (12.07%) | 73.78% (36.06 %) | 93.12% (10.99 %) | 88.90% (17.86 %) | 92.89% (13.53%) | 98.70% (3.77 %) | 86.06% (25.19 %) |

| . | Extensive CR programmes . | Intensive CR programmes . | Total, n (%) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copenhagen . | Bern . | Zwolle . | Santiago . | Nijmegena . | Parmaa . | Paris . | Ludwigshafena . | ||

| Offering and participation (n = 3471, elderly ACS/PCI/CABG patients) | |||||||||

| Screened patients, n | 613 | 856 | 757 | 663 | 89 | 367 | 587 | 242 | 4174 |

| ACS/PCI/CABG patients, n (%) | 537 (87.60%) | 637 (74.42%) | 746 (98.55%) | 594 (89.59%) | 29 (32.58%) | 270 (73.57%) | 457 (77.85%) | 201 (83.06%) | 3471 (83.16%) |

| Patients offered CR, n (%) | 454 (84.54%) | 541 (84.92%) | 688 (92.22%) | 434 (73.06%) | 29 (100%) | 213 (78.89%) | 246 (53.83%) | 201 (100%) | 2806 (80.84%) |

| Patients accepting CR, n (%) | 308 (67.84%) | 336 (62.11%) | 406 (59.01%) | 201 (46.31%) | 28 (96.55%) | 198 (92.96%) | 230 (93.50%) | 201 (100%) | 1908 (68.00%) |

| Adherence and compliance (n = 1607, EU-CaRE sampleb) | |||||||||

| EU-CaRE sample, n | 237 | 203 | 220 | 247 | 32 | 247 | 219 | 228 | 1633 |

| Early dropouts, n (%) | 28/228 (12.28%) | 3/203 (1.48%) | 0/219 (0.00%) | 34/247 (13.77%) | 0/32 (0.00%) | 3/241 (1.25%) | 0/219 (0.00%) | 0/218 (0.00%) | 68/1607 (4.23%) |

| Late dropouts, n (%) | 10/228 (4.39%) | 24/203 (11.82%) | 10/219 (4.57%) | 27/247 (10.93%) | 0/32 (0.00%) | 10/241 (4.15%) | 5/219 (2.28%) | 2/218 (0.92%) | 88/1607 (5.48%) |

| Total dropouts, n (%) | 38/228 (16.67%) | 27/203 (13.30%) | 10/219 (4.57%) | 61/247 (24.70%) | 0/32 (0.00%) | 13/241 (5.39%) | 5/219 (2.28%) | 2/218 (0.92%) | 156/1607 (9.71%) |

| Compliance, % median (IQR) | 88% (62–100%) | 94% (76.5–100%) | 100% (90–100%) | 92% (67–100%) | 100% (90.3–100%) | 95% (85–100%) | 100% (92–100%) | 100% (100–100%) | 97% (86–100%) |

| Compliance, % mean (SD) | 73.08% (33.57 %) | 81.81% (27.08 %) | 93.63% (12.07%) | 73.78% (36.06 %) | 93.12% (10.99 %) | 88.90% (17.86 %) | 92.89% (13.53%) | 98.70% (3.77 %) | 86.06% (25.19 %) |

Patients in Nijmegen, Ludwigshafen, and Parma were referred to the centre for cardiac rehabilitation.

Fifty-six patients who initially accepted to join the observational EU-CaRE study were finally excluded, with reasons: informed consent withdrawal, death, or lost to follow-up.

Cardiac rehabilitation offering and participation and adherence and compliance by centre

| . | Extensive CR programmes . | Intensive CR programmes . | Total, n (%) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copenhagen . | Bern . | Zwolle . | Santiago . | Nijmegena . | Parmaa . | Paris . | Ludwigshafena . | ||

| Offering and participation (n = 3471, elderly ACS/PCI/CABG patients) | |||||||||

| Screened patients, n | 613 | 856 | 757 | 663 | 89 | 367 | 587 | 242 | 4174 |

| ACS/PCI/CABG patients, n (%) | 537 (87.60%) | 637 (74.42%) | 746 (98.55%) | 594 (89.59%) | 29 (32.58%) | 270 (73.57%) | 457 (77.85%) | 201 (83.06%) | 3471 (83.16%) |

| Patients offered CR, n (%) | 454 (84.54%) | 541 (84.92%) | 688 (92.22%) | 434 (73.06%) | 29 (100%) | 213 (78.89%) | 246 (53.83%) | 201 (100%) | 2806 (80.84%) |

| Patients accepting CR, n (%) | 308 (67.84%) | 336 (62.11%) | 406 (59.01%) | 201 (46.31%) | 28 (96.55%) | 198 (92.96%) | 230 (93.50%) | 201 (100%) | 1908 (68.00%) |

| Adherence and compliance (n = 1607, EU-CaRE sampleb) | |||||||||

| EU-CaRE sample, n | 237 | 203 | 220 | 247 | 32 | 247 | 219 | 228 | 1633 |

| Early dropouts, n (%) | 28/228 (12.28%) | 3/203 (1.48%) | 0/219 (0.00%) | 34/247 (13.77%) | 0/32 (0.00%) | 3/241 (1.25%) | 0/219 (0.00%) | 0/218 (0.00%) | 68/1607 (4.23%) |

| Late dropouts, n (%) | 10/228 (4.39%) | 24/203 (11.82%) | 10/219 (4.57%) | 27/247 (10.93%) | 0/32 (0.00%) | 10/241 (4.15%) | 5/219 (2.28%) | 2/218 (0.92%) | 88/1607 (5.48%) |

| Total dropouts, n (%) | 38/228 (16.67%) | 27/203 (13.30%) | 10/219 (4.57%) | 61/247 (24.70%) | 0/32 (0.00%) | 13/241 (5.39%) | 5/219 (2.28%) | 2/218 (0.92%) | 156/1607 (9.71%) |

| Compliance, % median (IQR) | 88% (62–100%) | 94% (76.5–100%) | 100% (90–100%) | 92% (67–100%) | 100% (90.3–100%) | 95% (85–100%) | 100% (92–100%) | 100% (100–100%) | 97% (86–100%) |

| Compliance, % mean (SD) | 73.08% (33.57 %) | 81.81% (27.08 %) | 93.63% (12.07%) | 73.78% (36.06 %) | 93.12% (10.99 %) | 88.90% (17.86 %) | 92.89% (13.53%) | 98.70% (3.77 %) | 86.06% (25.19 %) |

| . | Extensive CR programmes . | Intensive CR programmes . | Total, n (%) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copenhagen . | Bern . | Zwolle . | Santiago . | Nijmegena . | Parmaa . | Paris . | Ludwigshafena . | ||

| Offering and participation (n = 3471, elderly ACS/PCI/CABG patients) | |||||||||

| Screened patients, n | 613 | 856 | 757 | 663 | 89 | 367 | 587 | 242 | 4174 |

| ACS/PCI/CABG patients, n (%) | 537 (87.60%) | 637 (74.42%) | 746 (98.55%) | 594 (89.59%) | 29 (32.58%) | 270 (73.57%) | 457 (77.85%) | 201 (83.06%) | 3471 (83.16%) |

| Patients offered CR, n (%) | 454 (84.54%) | 541 (84.92%) | 688 (92.22%) | 434 (73.06%) | 29 (100%) | 213 (78.89%) | 246 (53.83%) | 201 (100%) | 2806 (80.84%) |

| Patients accepting CR, n (%) | 308 (67.84%) | 336 (62.11%) | 406 (59.01%) | 201 (46.31%) | 28 (96.55%) | 198 (92.96%) | 230 (93.50%) | 201 (100%) | 1908 (68.00%) |

| Adherence and compliance (n = 1607, EU-CaRE sampleb) | |||||||||

| EU-CaRE sample, n | 237 | 203 | 220 | 247 | 32 | 247 | 219 | 228 | 1633 |

| Early dropouts, n (%) | 28/228 (12.28%) | 3/203 (1.48%) | 0/219 (0.00%) | 34/247 (13.77%) | 0/32 (0.00%) | 3/241 (1.25%) | 0/219 (0.00%) | 0/218 (0.00%) | 68/1607 (4.23%) |

| Late dropouts, n (%) | 10/228 (4.39%) | 24/203 (11.82%) | 10/219 (4.57%) | 27/247 (10.93%) | 0/32 (0.00%) | 10/241 (4.15%) | 5/219 (2.28%) | 2/218 (0.92%) | 88/1607 (5.48%) |

| Total dropouts, n (%) | 38/228 (16.67%) | 27/203 (13.30%) | 10/219 (4.57%) | 61/247 (24.70%) | 0/32 (0.00%) | 13/241 (5.39%) | 5/219 (2.28%) | 2/218 (0.92%) | 156/1607 (9.71%) |

| Compliance, % median (IQR) | 88% (62–100%) | 94% (76.5–100%) | 100% (90–100%) | 92% (67–100%) | 100% (90.3–100%) | 95% (85–100%) | 100% (92–100%) | 100% (100–100%) | 97% (86–100%) |

| Compliance, % mean (SD) | 73.08% (33.57 %) | 81.81% (27.08 %) | 93.63% (12.07%) | 73.78% (36.06 %) | 93.12% (10.99 %) | 88.90% (17.86 %) | 92.89% (13.53%) | 98.70% (3.77 %) | 86.06% (25.19 %) |

Patients in Nijmegen, Ludwigshafen, and Parma were referred to the centre for cardiac rehabilitation.

Fifty-six patients who initially accepted to join the observational EU-CaRE study were finally excluded, with reasons: informed consent withdrawal, death, or lost to follow-up.

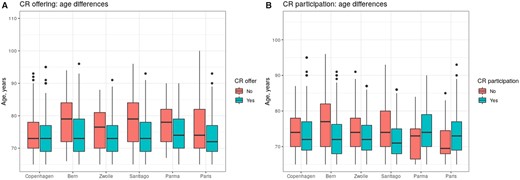

Older age led to lower referral to CR (Figure 1), with overall no sex differences after adjusting by age except for Zwolle and Copenhagen, where less women were offered CR (P < 0.05). Except for a larger proportion of Caucasian patients referred to CR in Zwolle, no other significant socio-demographic differences were detected. Regarding cardiovascular risk profile, those who were offered CR had a smaller percentage of smokers in Copenhagen and Zwolle (P < 0.05), and fewer patients with diabetes mellitus in Copenhagen, Bern, and Zwolle (P < 0.05). Other risk factors, including hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, and family history of cardiovascular disease, were balanced between offered and non-offered patients. Previous history of ACS was overall less frequent among offered patients, as well as cardiovascular (chronic heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and transient ischaemic attack) and non-cardiovascular comorbidity (nephropathy, peripheral artery, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease).

Age distribution of patients considering cardiac rehabilitation offering and participation. Box plots represent age distribution for patients who were offered cardiac rehabilitation vs. non-offered patients (A) and for participants vs. non-participants in cardiac rehabilitation (B) across centres in the EU-CaRE study.

The type of index event was involved in the offering process, and related to patient profile at each centre: i.e. CR was more often offered to patients after ACS in Bern, after PCI in Santiago and Parma, and after CABG in Bern, Zwolle, and Paris.

Participation in cardiac rehabilitation programmes

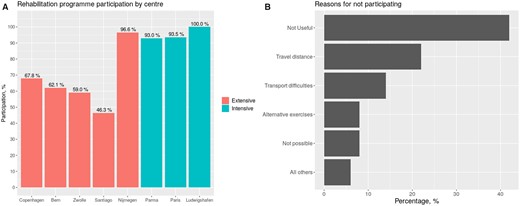

The mean participation was 68%. Higher rates were observed in intensive compared to extensive programmes (97.1% vs. 63.2%, P < 0.001), considering that patients in most inpatient programmes were directly referred to initiate CR (Table 2 and Figure 2). Main reasons for not participating in outpatient programmes were perceived lack of usefulness, transport difficulties to the centre and uptake of alternative exercise programmes (Figure 2).

Participation in extensive-outpatient and intensive-inpatient programmes. Participation rates in extensive and intensive cardiac rehabilitation programmes (A) and reasons for refusing participation (B) among elderly patients in the study. Patients in Nijmegen, Parma, and Ludwishafen were specifically referred to initiate cardiac rehabilitation.

As shown in Figure 1, participants in extensive CR programmes were younger, with no gender differences after adjusting by age except for Paris, with more male participants. There were overall no differences in ethnicity and employment status, except for a larger proportion of employed non-participants in Zwolle (P = 0.02). Patients living with others were more likely to participate, reaching statistical significance in Santiago and Zwolle (P < 0.001).

We observed a fairly equal distribution of cardiovascular risk factors between participants and non-participants. Concerning comorbidity, heart valve disease (P = 0.01) and peripheral artery disease (P = 0.001) in Bern, and atrial fibrillation in Zwolle and Copenhagen (P < 0.005) were less prevalent among participants, respectively. History of previous ACS tended to be less common among participants, significantly in Bern and Zwolle (P < 0.001).

The distribution of the index event also varied. Among participants, ACS was significantly more frequent in Paris and Parma, and CABG was more prevalent than PCI in all centres but for Santiago, which displayed opposite results.

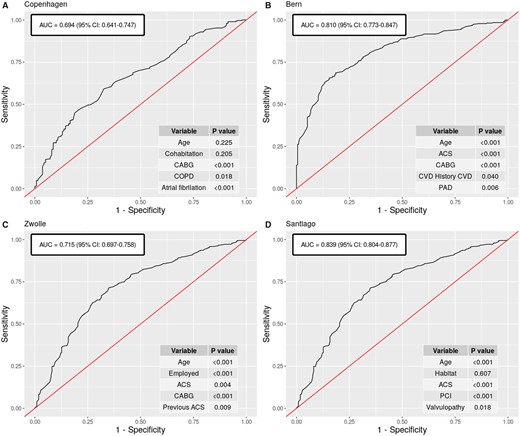

Multivariable predictive models for participation in extensive-outpatient CR programmes were developed for Zwolle, Copenhagen, Bern, and Santiago, with an overall good predictive capacity (AUC ≥ 0.70) (Figure 3) and good calibration as tested by the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (P > 0.05 for all models). With the only exception of Copenhagen, were age effect was not statistically significant, the remaining three centres showed a linear decrease in participation of 5–8% per year of age. Additional predictor variables (type of index event, particular socio-demographic characteristics, or comorbidities) behaved differently across centres. Therefore, the highly centre-specific nature of data prevented achieving a unique predictor model.

Predictive models of participation in extensive-outpatient programmes. Receiver operating characteristic curves for multivariable predictive models of participation in extensive-outpatient cardiac rehabilitation programmes in Copenhagen (A), Bern (B), Zwolle (C), and Santiago (D) and variables included in each model.

Adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programmes

Mean adherence to CR in this study surpassed 90%. Dropout rates were significantly higher in extensive programs compared to intensive programs (14.1% vs. 2.8%, P < 0.001) (Table 2). Main reasons for both early and late dropout were hospitalization and physical impairment, followed by travel distance/transport difficulties in case of early dropout.

Adverse events during CR were strongly associated with dropout (P < 0.001 in all centres). Thus, when excluding patients suffering adverse events, the highest dropout rates found in Santiago (25%), Copenhagen (17%), and Bern (13%), fell to 17%, 14%, and 7%, respectively.

Although there were no consistent ‘adherent’ and ‘non-adherent’ patient profiles across centres, women tended to leave the program significantly more often in Santiago (P = 0.01) and Bern (P = 0.03). Also, some comorbidity features were significantly related with dropout, such as rheumatoid arthritis (P = 0.003) and heart valve disease (P = 0.04) in Copenhagen, or COPD (P = 0.03) and nephropathy (P = 0.02) in Santiago, but no homogeneous pattern was found.

Compliance with cardiac rehabilitation programmes

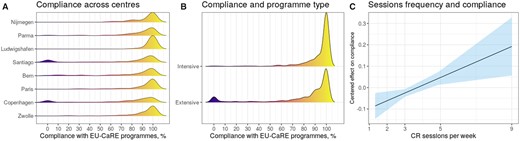

Global compliance with planned training sessions across centres was 86% (Table 1). Figure 4 depicts the estimated distribution of compliance with CR training, sorted by centres, and types of programmes. A peak at the upper tail of the distribution (highest compliance zone) is shown, together with a smaller peak at the lowest-compliance zone in Copenhagen and Santiago (Figure 4A), and in extensive programmes (Figure 4B). Even if overall compliance was high, this was affected by programme characteristics: the higher the frequency of training sessions, the higher the degree of compliance was observed (OR: 1.03, 95% CI = 1.01–1.06; P = 0.006) (Figure 4C). Accordingly, full compliance was significantly higher in intensive-inpatient than in extensive-outpatient programmes (66.0% vs. 38.8%%, P < 0.001).

Compliance across cardiac rehabilitation programmes and effect of training sessions’ frequency. Probability density function of compliance with training sessions is depicted by centre (A) and by type of programme (B). A peak at the upper level of the distribution is shown, revealing overall high compliance. The linear relationship between training frequency and compliance degree is displayed (C).

Compliance level according to patients’ characteristics was also studied. Despite significantly lower compliance among employed compared to retired patients in Bern (P = 0.044), no differences concerning other socio-demographic factors were detected in this elderly sample. Diabetics showed lower compliance compared to non-diabetics in Copenhagen (P = 0.028) and Bern (P = 0.005), but other cardiovascular risk factors did not show any differences. Certain comorbidities were associated with lower compliance, such as atrial fibrillation (Copenhagen, Zwolle and Parma, P < 0.05), obstructive apnoea in Santiago (P = 0.008), or rheumatoid arthritis (P = 0.008) and nephropathy (P < 0.001) in Parma. Regarding the index event, higher compliance was shown for CABG patients in Zwolle (P = 0.03).

Adverse events during CR were significantly associated with lower compliance levels in five centres, namely Zwolle (P = 0.011), Paris (P = 0.032), Bern (P < 0.001), Santiago (P = 0.001) and Parma (P = 0.002). Concerning symptoms, higher CCS angina class was linked to higher compliance in Paris (P = 0.046), while no differences were detected for dyspnoea assessed by New York Heart Association class in any of the centres.

Discussion

This study provides a portrait of current referral to, uptake of, adherence to and compliance with different models of CR programmes among elderly patients of Western Europe, identifying areas for improvement to achieve the best results. In patients with ACS of revascularization, CR offering surpassed 80% and participation was below 70%, significantly lower for older, comorbid patients. Inpatient programmes—where most patients were directly referred to initiate CR—presented higher participation. Adherence stayed above 90% and compliance above 85%, tackled by comorbidity and adverse events during the programme. Notably, adherence and compliance were significantly higher in intensive-inpatient programmes as compared to extensive-outpatient programmes.

Having formal contraindications for CR was the main reason for not offering it in this study, reflecting an overall correct referral system. However, there was a higher chance to offer CR to younger patients with lower comorbidity, and these were also more likely to participate. Women were slightly less likely to be offered and to participate in CR, although differences only remained significant in a minority of centres after age adjustment. These observations are concordant with previous research.14–16,22 Age may affect offer and participation in two manners: first, older patients are prone to higher comorbidity and complexity, discouraging physicians to refer them to CR. Secondly, there is a chance that elderly patients feel their potential benefit to enrol in CR is low.22,23 In fact, perceived ‘lack of usefulness’ was the main reason for refusing participation in our study. Nevertheless, older, comorbid patients may benefit from CR as much as their younger counterparts, and may even have a wider margin for improvement, including enhanced physical performance, management of comorbidity and iatrogenesis, and psychological and cognitive gains derived of socialization.10–13 We hypothesize that this perceived ‘lack of usefulness’ might be related with misunderstanding and misconceptions regarding CR and lifestyle changes.24 Also, choosing the right moment to provide this information and offer CR is important. Previous studies have suggested the immediate post-cardiac event period is probably not the best moment for the patient’s understanding and retaining of information due to the proximity of the shock, which might interfere with cognitive functioning.24,25 In fact, many patients did not remember having received information about CR during their hospital stay, and those who remembered it did not fully understand the CR offer.25

Transport issues constituted the second-factor hindering participation, as previously described.14,23 These are more likely to affect elderly patients, who may have difficulties to drive or arrange alternative transport.26,27 A systematic review of 62 studies involving 1646 patients (mean age 64.2 years) reported that participation in CR was strongly conditioned by the patient’s perception of suitability and scheduling of programmes, social factors and expectations, rather than perceptions of programme benefits.28 In this line, strategies to increase enrolment in CR, including: automatic referral of all eligible patients, physician endorsement, motivational communication, and specifically for older patients: post-discharge visits, intermediate phase programmes and peer support groups27,29 may also need to consider enhanced availability and ease of access to CR programmes. Novel delivery alternatives and tailored formulas, including home-based and telerehabilitation30–34 may help to overcome geographical and transport barriers.35 In this regard, results of the EU-CaRE multicentre randomized controlled trial involving mobile telemonitoring guided CR (mCR)18 will be separately presented.

Another main finding was the fact that shorter, intensive programmes displayed higher adherence compared to extensive programmes in this elderly population, which leads to two considerations. First, intensive programmes were usually inpatient (patients stayed in an inpatient facility during the programme), while extensive programmes were mostly outpatient (patients travelled to the CR centre), which may well have lessened transport issues in the first case. Secondly, shorter, intensive CR modalities may be a suitable option for patients who are unable or unwilling to attend an extended programme, contributing to enhanced adherence. Previous studies have reported improved physical and psychological parameters after short (4 weeks) intensive CR programmes.36,37 Others have stated the benefits of intensive, but considerably longer (12 weeks) interventions.38,39 Thus, the definition of ‘intensive’ and ‘short’ -arbitrarily settled in our study- may need clarification.

In the predictive models of participation developed for outpatient programmes, the index event was involved in participation and related to the characteristics of the centre. Thus, higher participation was associated with PCI in Santiago—where PCI was more frequent than CABG—and with CABG in the remaining centres—where CABG was balanced or slightly more frequent than PCI. Beatty et al.40 reported higher referral to CR after CABG than after PCI, as well as the strong influence of the hospital in which the procedure was performed on referral. These findings suggest a sort of ‘specialization’ of CR centres according to patients’ profile and management, and reflect their particular practice, screening process, and resources. Likewise, certain patient features were differently linked to participation and adherence across programmes, most probably translating diverse population profiles and particular constraints. Accordingly, the multicentre nature of data precluded developing a unique predictive model of participation.

Adherence and compliance in this cohort were remarkably high, with hospitalization or physical impairment being the principal reasons to prematurely leave the programme. Dropout was slightly more frequent among women and patients with comorbidity, and strongly associated with adverse events, as previously described.14,15 Conversely, no age effect was observed. Intensive programmes displayed the best results. Although there is limited evidence on the optimal ‘dose’ of CR, the greatest benefits in terms of death and ACS risk reduction have been reported for patients attending at least 36 sessions.41 However, longer programmes may carry a greater risk of dropout, which should be balanced against potential benefits. In our study, we found a linear relationship between frequency of training sessions and compliance, suggesting that concentrated training formulas could possibly work better in this older population and tackle dropout.

Limitations

This study is subject to several limitations. First, this study was challenged by the multicentre and heterogeneous nature of data, including different social settings, types of CR programmes, and patients’ characteristics. Comparing in- and outpatient CR was complicated by almost all centres only offering one or the other, so participation rate may not be ascribed to either in- or outpatient programmes but rather to other factors inherent to different societies. Secondly, offering rates in this study were markedly high. This may have been based on a selection bias at screening: the denominator to calculate offering-rate was not extracted from hospital data considering all patients aged ≥65 with an eligible diagnosis,42 but considering all screened patients meeting both criteria, possibly reducing the denominator and leading to offering rate overestimation. Alternatively, participation in this study may have led to extra efforts of the CR recruitment teams leading to higher than usual CR offering and participation rates. Additionally, patients in Nijmegen (outpatient programme), Parma and Ludwigshafen (inpatient programmes) were specifically referred to initiate CR, explaining ≈100% participation rates. For this reason, predictive models for participation were only performed for outpatient programmes, excluding Nijmegen. Thirdly, we acknowledge missing data concerning reasons for not offering CR (28%), for not participating (6%), and for early (12%) and late dropout (18%). Also, compliance was defined in this study as the proportion of training sessions attended by patients, but compliance with other essential components and goals of a comprehensive CR programme were not considered in this analysis, leading to a ‘partial’ evaluation of results.

Clinical implications

A number of clinical implications can be derived from this study. First, the great heterogeneity found across patients and CR programmes in this study offers the opportunity to learn from different practices and highlights that it is unlikely that a single model suits all patients: current models should adapt to the particular needs of the target population, rather than offering a ‘one-size-fits-all’ formula. Second, raising awareness on potential health and well-being gains of CR for elderly patients—in view of many elderly patients believing they would not be benefited by CR—, seeking for strategies to overcome geographical barriers, and developing tools for early management of comorbidity are still pending subjects to improve their participation and adherence. Third, shorter, intensive programmes might be considered to increase adherence and compliance of elderly patients who decline extensive programmes, especially if similar benefits are demonstrated from different types of programmes.37 Finally, the ability to predict and identify patients less likely to uptake CR would allow emphasizing inpatient cardiac education and outpatient recommendations in such cases, and avoid early dropout.

Conclusion

In this European cohort of elderly patients, high CR offering rates (>80%) and very high adherence (>90%) and compliance (>85%) proportions contrasted with moderately high participation rates (<70%). Older age and higher comorbidity were related to lesser offering and participation, while comorbidity and adverse events were associated with lower adherence and compliance. Intensive-inpatient CR programmes showed higher completion than extensive-outpatient CR programmes, suggesting this formula may be considered a suitable option for certain elderly patients.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Manuela Sestayo for her valuable contribution to the development of the study.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: this project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement: 634439) and from the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation for the Swiss consortium partner.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Comments