-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rod S Taylor, Sally Singh, Personalised rehabilitation for cardiac and pulmonary patients with multimorbidity: Time for implementation?, European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, Volume 28, Issue 16, December 2021, Pages e19–e23, https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487320926058

Close - Share Icon Share

The current status quo?

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) and pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) are traditionally commissioned and delivered as single disease services in Europe, North America and other developed country settings. For CR, the focus has traditionally been on patients with an index diagnosis of myocardial infarction (MI), post-revascularisation or heart failure (HF).1–4 For PR, the index diagnosis is most commonly chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and, unlike CR, more likely not to be after an acute exacerbation but rather during a stable phase of the disease process.5,6

These current CR and PR models reflect the existing evidence base and follow the medical model of the delivery of care. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have traditionally been undertaken in CR targeting specific heart disease indications. As reflected by recent Cochrane systematic reviews and meta-analyses, by far and away the largest volume of RCT evidence is in rehabilitation programmes designed for post-MI and revascularisation patients (63 RCTs, 14,486 patients) and HF (44 RCTs, 5783 patients). Similarly, in PR patients the evidence is stacked towards those with COPD (65 RCTs, 3822 patients).7–9

Consequently, European and North American clinical guidelines follow these single disease pathways and provide class I recommendations for CR and PR in these specific indication groups.10–15

So, what’s the problem?

Given the much smaller body of RCT evidence for other index cardiovascular and respiratory indications, including atrial fibrillation,16 HF with preserved ejection fraction,10,11 valve disease and post-valve surgery,17 peripheral vascular disease18 and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and bronchiectasis,19 clinical guidelines do not recommend rehabilitation for these ‘orphan’ populations. Given that these chronic conditions are associated with high levels of disability, loss in health-related quality of life (HRQoL), increased risk of morbidity and high health costs,20–22 there is clearly a high unmet rehabilitation need.

Furthermore, whilst referred for CR or PR for specific indication (post-MI, revascularisation, HF and COPD) patients typically do not present to rehabilitation programmes with a single disease but have a number of comorbidities. For example, the large Participants in Heart Failure: A Controlled Trial Investigating Outcomes of Exercise Training (HF-ACTION) trial (2331 patients with reduced ejection HF) reported at entry to the study a number of co-morbidities: 59% with hypertension, 21% atrial fibrillation or flutter and 32% with diabetes mellitus.23 Among those referred for PR, the proportion of patients with at least one co-existing condition is reported to vary from 51–96%.24 A growing number of epidemiological studies have reported a high prevalence of so-called multimorbidity, commonly defined as the presence of two or more chronic medical conditions in an individual, in the general population. For example, Barnett et al. found 23% of patients registered across 314 medical practices in Scotland had evidence of multimorbidity, and increasing prevalence with increased age.25 Importantly, compared with patients with only one chronic medical condition, patients with multimorbidity are at higher risk of dying prematurely, being admitted to hospital, having longer stays in hospital and reduced HRQoL.26,27

With its focus on a single medical condition, the traditional model of disease-specific rehabilitation does not meet the challenges of multimorbidity, overlooking the potential interaction of multiple diseases and their management, and some cases may even exclude people with multimorbidity. Despite the high prevalence of cardiovascular disease in individuals with COPD, the challenges of managing this are not formally addressed in PR and potentially necessitate attendance at a CR programme for bespoke cardiac disease management support.28 The recent study of Sumner and colleagues showed that presence of mental health conditions in CR patients such as anxiety and depression can lead to reduced programme adherence.29

What’s the way forward?

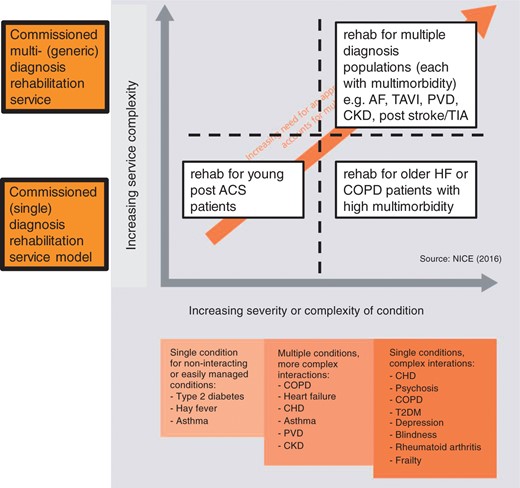

We would argue that the replication of disease-specific rehabilitation programmes for additional specific cardiac and pulmonary diseases, such as atrial fibrillation, peripheral vascular disease or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, is not the answer. Instead, we need to adapt to the change in population demographics and look to provide a model of personalised multimorbidity rehabilitation that meets the needs of patients, irrespective of their cardiovascular or pulmonary index diagnosis (see Figure 1). Key arguments for such a new multimorbidity rehabilitative model include:

Development of a personalised multimorbidity rehabilitation model. The axes chart the increasing complexity of service delivery against the increasing complexity of the disease/s. The complexity of the rehabilitation services increases from the bottom left quadrant where a single indication non-complex programme is offer through to the top right quadrant whereby multiple complex disease each with multimorbidity are offered rehabilitation within a single overarching programme. Adapted from NICE multimorbidity guidelines https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng56. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HF: heart failure; ACS: acute coronary syndrome; AF: atrial fibrillation; CHD: coronary heart disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; PVD: peripheral vascular disease; T2DM: type-2 diabetes; TAVI: trans-aortic value invention; TIA: trans-ischemic attack; NICE: National Institute for Care Excellence.

Sustainability: In today’s financially challenged health service, healthcare commissioners/purchasers are likely to consider of expansion of disease-specific rehabilitation services as inefficient and unsustainable. Instead, they would be more attracted to a programme that caters for patients with multimorbidity as a more appropriate and cost-effective model of care.

Holistic: It would seem likely that failure to consider the impact of multimorbidity on the wellbeing and functionality and, for example ‘just rehabilitate their heart failure’ would much diminish the potential benefits of rehabilitation. Given that it is common for PR and CR patients to have multiple chronic conditions, it is increasingly likely that many of their important clinical problems will not be directly related to their cardiac or respiratory disease. We know from qualitative research that treating one condition at a time is inconvenient and unsatisfactory for the patient with the chronic conditions.30

Inclusivity: Personalised multimorbidity rehabilitation presents an opportunity to develop the model by which to extend services to other important long-term conditions that would be amenable to rehabilitation, and highlighted earlier in this commentary, such as atrial fibrillation. Furthermore, this model could be extended to include other patient groups with, for example, post-trans-ischemic attack/mild stroke or peripheral vascular disease.

So, what do we need to do next?

Unlike disease-specific rehabilitation, currently there is little research literature or clinical advice around a model of personalised multimorbidity rehabilitation. The recently published NHS England 10-year long term plan31 has proposed a symptom-based breathlessness programme after some early pilot work combining COPD and HF, based upon early work by Evans et al., showed that it is clinically intuitive to combine COPD and HF in this model given the common problem of breathlessness, and the prevalence of co-existing COPD and HF.32

The recently updated Cochrane review of interventions for multimorbidity identified a total of 29 RCTs focusing on either specific combinations of two health conditions (e.g. cardiac disease and diabetes) or a broader range of conditions and tended to focus on elderly people.33 While the interventions identified all involved multiple components, they were divided broadly into organisational (e.g. case management or addition of a pharmacist to the clinical care team) or primarily patient-oriented interventions (e.g. self-management support groups or community-based diet and exercise programmes). Overall, these RCTs indicated that there were little or no differences in patient outcomes, including clinical outcomes (e.g. blood pressure, glycaemic control), HRQoL, level of health service use, and medication use. However, none of these trials appeared to be based on a model of personalised multimorbidity rehabilitation.

We are aware of two small developmental studies that have specifically focused on multimorbidity rehabilitation. The first is a pilot RCT in single centre in Australia to evaluate the feasibility of an eight-week rehabilitation programme of supervised exercise and education (based on principles of CR and PR) in 16 patients with multimorbidity (physician diagnosis of two or more chronic conditions).34,35 The authors reported that their intervention was acceptable (71% intervention completion) and an RCT design (comparing generic rehabilitation with usual care comparator of no rehabilitation) was feasible. Although not formally statistically powered to compare groups, a higher mean improvement was seen in the six-minute walk distance of 44 m with rehabilitation compared with control of 23 m. However, the study had a low uptake: 100 patients needed to be screened in order to recruit 18 patients to the study. The second study reports the Healthy and Active Rehabilitation Programme (HARP), a model of rehabilitation for people living in Ayrshire in Scotland with multimorbidity, and established in 2015.36 The authors report that the HARP model has been developed to specifically focus upon deprived and rural communities and those with high unscheduled care demand (i.e. cardiac or pulmonary disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes and at risk of falls). Again, developed from existing models of CR and PR, HARP consists of a comprehensive patient assessment followed by a 10-week exercise and education programme. Interviews with multimorbid patients indicated that the HARP programme was well-received and perceived to improve confidence and motivation for physical activity and other healthy behaviours.

In the absence of an established evidence base, there is an urgent need for research into the acceptability, efficacy and cost-effectiveness of personalised models of rehabilitation for multimorbidity. We close this commentary with identification of the key research questions that need to be addressed:

What multimorbidity patients do we target for rehabilitation? There is probably a good argument for multimorbidity rehabilitation programmes to incorporate the ‘orphan’ medical conditions (i.e. indications with existing RCT evidence of benefit of CR or PR but no current commissioned service) outlined earlier in this commentary, such as atrial fibrillation, peripheral vascular disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. However, we need to think more broadly and ask the question of which groups of medical conditions indications might be best served and have the highest need for rehabilitation. To address this, we need research on large epidemiological data sets to examine the groups (or clusters) of disease indications that might cluster according to key health service outcomes, such as, risk of 30-day hospitalisation and mortality. The association of multimorbidity with frailty is an important consideration. Identification of individuals who are ‘pre-frail’ and at high risk of negative future health outcomes may offer an approach to the identification of those multimorbid patients who may best benefit from a model of personalised multimorbidity rehabilitation.37

How do we develop a personalised rehabilitation model that best addresses multimorbidity? At the heart of existing comprehensive CR and PR programmes is a thorough initial patient assessment enabling a personalised rehabilitation programme around the intervention pillars of exercise/physical activity prescription, education and psychological support. The fundamentals of exercise prescription should also apply to multimorbidity. Instead the challenge is probably more focused on the broader educational component and the specifics that relate to specific disease management when serving a multimorbidity population. The fundamentals of healthy lifestyle behaviours are similar irrespective of the index disease; this might include anxiety management, healthy eating, exercise behaviours and smoking cessation. There may be a need to deliver bespoke disease-specific education, e.g. medication management, and specific symptom control. It is also key not to underestimate the challenges of implementation of multimorbidity rehabilitation into a health service that is based on the traditional medical model of single medical conditions. Programmes of research leading to multimorbidity rehabilitation interventions that are likely implementable and scaleable will therefore need extensive stakeholder involvement with patients, clinicians and service providers/commissioners.

What study designs should be used to evaluate multimorbidity rehabilitation programmes? Evidence generation for CR and PR has traditionally focused on the question of efficacy, typically undertaking parallel group RCT designs that allocate patients with a specific medical condition to either a rehabilitation intervention or control and collect a disease-specific primary outcome.7–9 However, more innovative study designs are likely to be needed for the evaluation of multimorbidity rehabilitation. By definition, study populations need to be broader in their inclusion and include patients with two or more diseases. We would also argue that study designs need refocus on the question of future health service implementation. This may require cluster RCT design allocation where multimorbidity rehabilitation models are introduced at a service level (e.g. hospital, community locality, geographic region). The step-wedge RCT design allows the introduction of multimorbidity rehabilitation intervention across all service providers yet also retains an experimental element that allows an unbiased assessment of efficacy or effectiveness.38 Research studies will also need to address the question of the most appropriate comparator or control (i.e. no rehabilitation or traditional single-disease rehabilitation) and how best to capture patient-related outcomes in this setting. This requires a move away from disease-specific measures and instead the use of across-disease metrics of patient and health service benefit, including generic HRQoL and risk of hospitalization.39

In conclusion, we should not abandon our existing CR or PR programme for an untested, multimorbidity model of rehabilitation. Instead the challenge is for our indication-specific model of cardiopulmonary rehabilitation is to evolve, building on existing successes to more comprehensively address the needs of people with multimorbidity. Alongside this, we need to develop a robust evidence base to inform best clinical practice with the development of an acceptable, effective and good-value-for-money model of personalised rehabilitation for cardiac and pulmonary patients with multimorbidity.

Author contribution

RST and SS both contributed to the conception of this article. Both drafted and critically revised the manuscript and accountable for all aspects of work.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the discussions of the Personalised Exercise-Rehabilitation For People with Multimorbidity (PERFORM) research collaboration that contributed to development of this commentary and thanks to Dr Hayes Dalal who commented on an early draft of this paper.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury Met al.

NHS England. NHS England 10 year plan, https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-term-plan/ (2019, accessed 1 January 2020).

Comments