-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Maria L Krogager, Christian Torp-Pedersen, Short-term mortality risk of different plasma potassium levels in patients treated with combination antihypertensive therapy, European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, Volume 28, Issue 11, November 2021, Pages e15–e17, https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487320925220

Close - Share Icon Share

We have shown a narrow potassium interval, namely 4.1–4.7 mmol/L, to be associated with increased survival in patients with hypertension treated with combination therapy compared with values outside this interval.1 However, in that study we were unable to differentiate between serum and plasma potassium due to lack of information on laboratory analysis codes. Therefore, we referred to both plasma and serum potassium measurements as ‘serum potassium’. Several studies have suggested that blood draws taken under suboptimal conditions might result in a substantial difference between the two methods of measuring potassium.2,3 Drogies et al.3 demonstrated that in patients with hypokalaemia the lower reference level is quite similar in both serum and plasma (difference <0.1 mmol/L). Nevertheless, a more significant difference was observed in patients with hyperkalaemia (difference >0.5 mmol/L). Plasma potassium measurements are considered superior to serum potassium measurements.4 We therefore decided to examine whether the results in our previous paper can be replicated using plasma potassium measurements only.

We refer to ‘Short-term mortality risk of serum potassium levels in hypertension: A retrospective analysis of nationwide registry data’1 for detailed information about the methods.

To summarize, we defined hypertension as use of at least two classes of antihypertensive drugs in two concomitant quarters. Patients entered the study in the second quarter and this time is referred to as hypertension date. We used this definition of hypertension for different reasons. First, this is a register study, where identification of patients with hypertension based on monotherapy only is difficult as antihypertensive drugs can be used for other cardiovascular diseases as well. Second, identification of patients with hypertension based on diagnosis code alone would exclude patients with uncomplicated hypertension that are treated and monitored by the general practitioner. Third, Olesen et al.5 showed a high positive predictive value and specificity when defining hypertension as treatment with two classes of antihypertensive drugs.

We retained first plasma potassium measurement within 90 days from hypertension date. The statistical analyses were performed on patients stratified in seven potassium groups. According to the Drogies,3 hypokalaemia was defined as plasma potassium concentrations <3.5 mmol/L and hyperkalaemia as levels >4.6 mmol/L. All-cause mortality within 90 days in the seven plasma potassium strata was the primary outcome of this study and was assessed using Cox proportional hazard model. Potassium interval 4.1–4.4 mmol/L was used as reference in the analyses. Secondary outcome was cardiovascular death with other causes of death as competing risk.

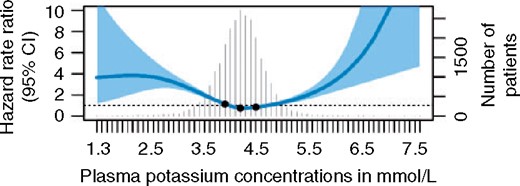

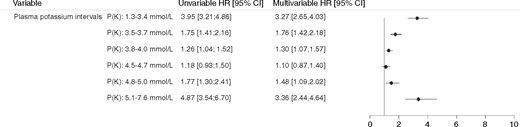

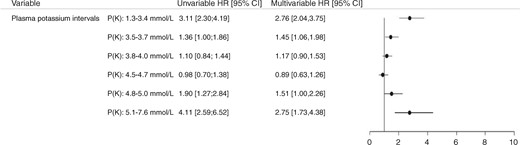

From 1995 to 2018, we identified 26,167 patients treated for high blood pressure who had available plasma potassium measurements within 90 days from hypertension date. The event was observed in 891 patients. Restricted cubic spline figure showed a U-shaped relationship between potassium and 90-day mortality, with highest survival within the interval 3.8–4.4 mmol/L (Figure 1). Adjusted Cox proportional hazard model showed that hypokalaemia and potassium intervals 3.5–3.7 mmol/L and 3.8–4.0 mmol/L levels were associated with increased mortality (hazard ratio 3.27, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.65–4.03; hazard ratio 1.76, 95% CI 1.42–2.18; hazard ratio 1.30, 95% CI 1.07–1.57 respectively), compared with the reference (Figure 2). Hyperkalaemia was also associated with increased risk of death within 90 days (4.8–5.0 mmol/L: hazard ratio 1.48, 95% CI 1.09–2.02 and 5.1–7.6 mmol/L: hazard ratio 3.36, 95% CI 2.44–4.64). We also observed that plasma potassium concentrations below 3.8 mmol/L and above 5.0 mmol/L were associated with cardiovascular death (Figure 3).

Restricted cubic spline curve showing the adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality as a function of second potassium measurements. Knots: the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles of potassium. Model adjusted for age, sex, antihypertensive therapy, heart failure, ischaemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke and diabetes mellitus. CI: confidence interval

All-cause mortality in patients with hypertension stratified by potassium intervals. Reference: 4.1–4.4 mmol/L. Adjusted for age, sex, antihypertensive therapy, heart failure, ischaemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke and diabetes mellitus. HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval

Risk of cardiovascular death (n = 435) within 90 days in patients with hypertension stratified by potassium intervals. Non-cardiovascular deaths (n = 456) were accounted as competing risk. Adjusted for age, sex, antihypertensive therapy, heart failure, ischaemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke and diabetes mellitus. The top three causes of non-cardiovascular death: 222 malignancy, 66 diseases of the respiratory tract (excluding malignancy), 19 diseases of the gastrointestinal tract (excluding malignancy). For 60 patients no cause of death was registered.

This retrospective study using Danish nationwide registers confirmed the results observed in our previous study, namely that plasma potassium concentrations outside the interval 4.1–4.7 mmol/L are associated with increased mortality risk within 90 days.

Both studies suggest that aiming and maintaining potassium concentrations in the middle of the currently used reference interval might improve outcome in patients with hypertension. It is likely that the association of borderline hypokalaemia and hyperkalaemia with short-term mortality can partly be explained by further decrease and increase in potassium, respectively. We have tested this hypothesis in patients with chronic heart failure and initial hypokalaemia.6 We found that patients with persistent hypokalaemia and patients who developed hyperkalaemia (after an episode with hypokalemia) had increased short-term mortality risk. Close monitoring of potassium in patients with dyskalaemias and borderline values is recommended.

Author contribution

Conception or design of the work: MLK, CT-P. Acquisition of data: MLK, CT-P. Analysis and interpretation of data: MLK. Drafted the manuscript: MLK. Critically revised the manuscript: CT-P. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Comments