-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Emma E Thomas, Rebecca Chambers, Samara Phillips, Jonathan C Rawstorn, Susie Cartledge, Sustaining telehealth among cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation services: a qualitative framework study, European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, Volume 22, Issue 8, November 2023, Pages 795–803, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvac111

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

As we move into a new phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, cardiac and pulmonary services are considering how to sustain telehealth modalities long-term. It is important to learn from services that had greater telehealth adoption and determine factors that support sustained use. We aimed to describe how telehealth has been used to deliver cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation services across Queensland, Australia.

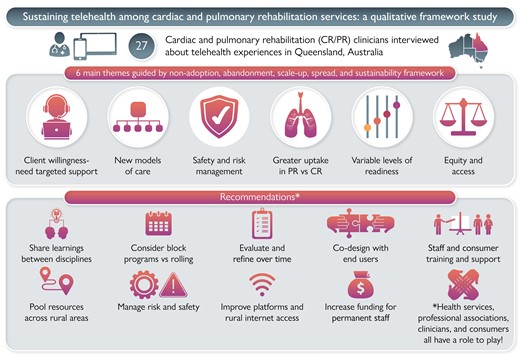

Semi-structured interviews (n = 8) and focus groups (n = 7) were conducted with 27 cardiac and pulmonary clinicians and managers from health services across Queensland between June and August 2021. Interview questions were guided by Greenhalgh’s Non-adoption, Abandonment, Scale-up, Spread, and Sustainability framework. Hybrid inductive/deductive framework analysis elicited six main themes: (i) Variable levels of readiness; (ii) Greater telehealth uptake in pulmonary vs. cardiac rehabilitation; (iii) Safety and risk management; (iv) Client willingness—targeted support required; (v) Equity and access; and (vi) New models of care. We found that sustained integration of telehealth in cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation will require contributions from all stakeholders: consumers (e.g. co-design), clinicians (e.g. shared learning), health services (e.g. increasing platform functionality), and the profession (e.g. sharing resources).

There are opportunities for telehealth programmes servicing large geographic areas and opportunities to increase programme participation rates more broadly. Centralized models of care serving large geographic areas could maximize sustainability with current resource limitations; however, realizing the full potential of telehealth will require additional funding for supporting infrastructure and workforce. Individuals and organizations both have roles to play in sustaining telehealth in cardiac and pulmonary services.

New models of care (e.g. pooling of resources across sites) needs to be considered to ensure telehealth options can continue in areas with limited staff resources and to also increase patient numbers.

Remote patient monitoring needs to be more widely incorporated to enhance telehealth-delivered exercise aspects of secondary prevention programmes.

We provide recommendations developed around the Non-adoption, Abandonment, Scale-up, Spread, and Sustainability framework to support the sustainable integration of telehealth models within cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation services.

Introduction

Secondary prevention (e.g. the management of disease post-diagnosis) programmes such as cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation provide long-term self-management strategies through the provision of exercise sessions and education in lifestyle change (i.e. medication adherence, healthy eating, smoking cessation). In Australia, brief information is provided during the acute hospital stay; however, rehabilitation is largely delivered as outpatients (Phase II care) in the community or hospital settings. Programmes are typically 6–12 weeks in duration.1 Despite the effectiveness of these programmes,2, 3 attendance rates are persistently low.4 Only around 10% of eligible Australians attend facility-based programmes.5

Many preventative services experience inconsistent participation rates at some stage. The reasons why people do not attend facility-based cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation are multi-faceted but typically include the geographical distance from the service, transport issues, or work and carer responsibility.6–8 Consumers at highest risk of future cardiovascular events are reported least likely to attend, often due to a lack of risk factor knowledge that contributes to their high risk in the first place.9 Alternate delivery models such as telehealth can address many of these attendance barriers and have the potential to improve health outcomes for consumers and economic benefits for health systems.10 For example, increasing uptake of cardiac rehabilitation in Australia by 30% and 65% was estimated to have net annual financial savings of AUD$46.7million and AUD$86.7 million, respectively.11, 12

As part of the COVID-19 emergency response, some cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation services across Australia rapidly transitioned to delivering services using telehealth (including telephone, video consultations, and remote patient monitoring).13, 14 There now exists an ideal opportunity to determine how telehealth can become a sustainable part of cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation services. Queensland is an ideal location to investigate this further, given the state’s highly developed telehealth infrastructure, large regional and remote population, and well-established state-wide clinical networks.

Therefore, the aim of this research project was to describe how telehealth was used to deliver cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation services across Queensland. This information was used to produce practical recommendations to guide the sustained delivery of telehealth in cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation beyond the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study design

This study used qualitative research methods including a framework approach and hybrid inductive/deductive analysis,15 which is described in greater detail below.

Participant recruitment and setting

Cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation clinicians and managers from nursing, physiotherapy, and exercise physiology backgrounds were recruited from health services across Queensland (Australia). Queensland is a large state in Australia’s northeast; it covers over 1.8 million km2 (7× the size of Great Britain) and has a population of ∼5 million people who are dispersed across metropolitan, regional, and remote areas. Public health services in Queensland are run by the state health department. Purposeful sampling ensured participants were recruited from a range of health services including metropolitan (major cities), regional (e.g. cities and urban centres outside of southeast Queensland), and rural/remote areas (areas that are further than 15 km from a town with <50 000 residents).16 Participants were recruited via email membership lists of the Queensland Australian Cardiovascular and Rehabilitation Association, the Australian Pulmonary Rehabilitation Network, and Queensland Health state-wide cardiac and pulmonary networks, and provided with details on the purpose of the research and participant requirements.

Data collection and analysis

Semi-structured qualitative interviews and focus groups were guided by the Non-adoption, Abandonment, Scale-up, Spread, and Sustainability (NASSS) framework (see Supplementary material online, File SB for the interview guide).17 This framework is specific to evaluating the implementation of health technologies and predicting their future success.18 It was created by reviewing the evidence base of previous technological interventions implemented for health. It involves investigating a technological innovation at a health service across seven domains that are (i) the condition, (ii) the technology, (iii) the value proposition, (iv) the adopter system (staff and patients), (v) the organization, (vi) the wider context (e.g. socio-cultural), and (vii) how factors interact and adapt over time. Reporting of findings was guided by the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist (Supplementary material online, File SA).

Interviews (∼ 30 min) and focus groups (∼45–60 min) took place between June and August 2021 using the Zoom™ videoconferencing platform (https://zoom.us/). While focus groups were usually preferred, interviews were offered to staff who had limited availability. Interviews were also conducted with managers, so that clinicians in the focus groups felt they could speak more freely, rather than having their supervisors present. Interviews and focus groups were conducted by female authors E.E.T. (cardiovascular researcher with a PhD) and R.C. (pulmonary clinician and researcher). We used the same semi-structured, open question, interview guide for interviews and focus groups. This ensured discussions could cover the broad range of constructs known to influence the implementation and sustainability of technologies in healthcare, while also allowing participants to focus on concepts that were most salient to their telehealth experience. Interviewers had no relationship with participants prior to study commencement.

Interviews were automatically transcribed via the Zoom™ software. Each author (E.E.T., R.C., S.P., J.R., and S.C.) was involved in reviewing transcripts for accuracy and de-identification. This process enabled the whole authorship team to familiarize themselves with the data. It also enabled multiple authors who have qualitative training or experience (E.E.T., S.C., and J.R.) to be involved in the coding/indexing process. We then conducted the analysis in two steps: (i) open coding to assess for and develop main themes and (ii) mapping themes back to the NASSS framework to undertake a framework analysis. A coding frame was jointly developed, tested, and refined before being applied to all transcripts. Coding was completed using NVivo 12 software. A full description of our data analysis steps is summarized in Table 1.

| Step . | Process . | Team members involved . |

|---|---|---|

| Familiarization and data immersion | ||

| 1 | All authors were involved in reviewing a number of transcripts for accuracy and to assist with de-identification. This assisted with the authors being familiar and immersed within the data, before analysis commenced. | All authors |

| Coding | ||

| 2 | We conducted open, inductive coding to assess for and develop main themes. | E.E.T., J.R., S.C. |

| 3 | We then conducted deductive coding of themes back to the NASSS framework, thus conducting a deductive framework analysis. | E.E.T., J.R., S.C. |

| 4 | This developed a coding frame which was tested on additional transcripts and refined, before being applied to all transcripts. | E.E.T., J.R., S.C. |

| Step . | Process . | Team members involved . |

|---|---|---|

| Familiarization and data immersion | ||

| 1 | All authors were involved in reviewing a number of transcripts for accuracy and to assist with de-identification. This assisted with the authors being familiar and immersed within the data, before analysis commenced. | All authors |

| Coding | ||

| 2 | We conducted open, inductive coding to assess for and develop main themes. | E.E.T., J.R., S.C. |

| 3 | We then conducted deductive coding of themes back to the NASSS framework, thus conducting a deductive framework analysis. | E.E.T., J.R., S.C. |

| 4 | This developed a coding frame which was tested on additional transcripts and refined, before being applied to all transcripts. | E.E.T., J.R., S.C. |

NASSS, Non-adoption, Abandonment, Scale-up, Spread, and Sustainability.

| Step . | Process . | Team members involved . |

|---|---|---|

| Familiarization and data immersion | ||

| 1 | All authors were involved in reviewing a number of transcripts for accuracy and to assist with de-identification. This assisted with the authors being familiar and immersed within the data, before analysis commenced. | All authors |

| Coding | ||

| 2 | We conducted open, inductive coding to assess for and develop main themes. | E.E.T., J.R., S.C. |

| 3 | We then conducted deductive coding of themes back to the NASSS framework, thus conducting a deductive framework analysis. | E.E.T., J.R., S.C. |

| 4 | This developed a coding frame which was tested on additional transcripts and refined, before being applied to all transcripts. | E.E.T., J.R., S.C. |

| Step . | Process . | Team members involved . |

|---|---|---|

| Familiarization and data immersion | ||

| 1 | All authors were involved in reviewing a number of transcripts for accuracy and to assist with de-identification. This assisted with the authors being familiar and immersed within the data, before analysis commenced. | All authors |

| Coding | ||

| 2 | We conducted open, inductive coding to assess for and develop main themes. | E.E.T., J.R., S.C. |

| 3 | We then conducted deductive coding of themes back to the NASSS framework, thus conducting a deductive framework analysis. | E.E.T., J.R., S.C. |

| 4 | This developed a coding frame which was tested on additional transcripts and refined, before being applied to all transcripts. | E.E.T., J.R., S.C. |

NASSS, Non-adoption, Abandonment, Scale-up, Spread, and Sustainability.

This framework analysis approach, as described by Gale et al.,19 was used to determine major themes. The framework analysis approach involves familiarization of the data, identifying a thematic framework, indexing, charting, and data interpretation.19 A matrix was then developed to bring key findings together (Supplementary material online, FileSC) and guided discussions and interpretation of the data. Participants were not provided copies of the transcript and did not give feedback on the findings.

Trustworthiness and rigour

The study took into account the four constructs of trustworthiness (as per Guba)20: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Bias was minimized by having participants from a range of staffing levels, settings, disciplines, and geographic locations. The credibility of the study was increased by the involvement of the state-wide pulmonary (R.C.) and cardiac (S.P.) rehabilitation coordinators who had familiarity with service provision across the state and could triangulate findings from their perspective. Our researchers also were from different states with representation from both cardiac and pulmonary research. Transferability was enhanced by having a range of clinicians from across the state involved in the study, as well as the inclusion of different professionals (e.g. nursing, physiotherapy) and roles (e.g. managerial vs. clinical). To increase dependability, all authors coded the same transcript, the consistency of coding was checked, and the coding frame was amended to ensure consistency. Finally, five meetings were held with all authors to review and discuss coding and development of themes which improved the confirmability of results.

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from The University of Queensland’s Human Research Ethics Committee (#73464), and verbal consent was recorded for all participants.

Results

Demographics

A total of 27 participants took part, including eight individual interviews (∼30 min in duration) and seven focus groups (mean 2.6 per group; ∼45–60 min in duration) (Table 2). Three participants were unable to complete data collection, mostly due to an unexpectedly high clinical load.

| Position . | Categories . | Count (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female Missing/prefer not to say | 19 (70) 3 (11) |

| Age in years | Median: 47.5 (IQR: 37–53) | |

| Missing/prefer not to say | 5 (19) | |

| Professional role | Team leader/director | 5 (19) |

| Clinician | 22 (81) | |

| Professionalgroup | Clinical nurse | 14 (52) |

| Physiotherapist | 11 (41) | |

| Exercise physiologist | 2 (7) | |

| Years working in allied health | Median: 10 (IQR: 6–17) | |

| Missing/prefer not to say | 6 (22) | |

| Clinical area | Cardiac rehabilitation | 8 (30) |

| Pulmonary rehabilitation | 8 (30) | |

| Both cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation | 11 (40) | |

| Geographic location | Metropolitan Regional/remote | 12 (44) 15 (56) |

| Position . | Categories . | Count (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female Missing/prefer not to say | 19 (70) 3 (11) |

| Age in years | Median: 47.5 (IQR: 37–53) | |

| Missing/prefer not to say | 5 (19) | |

| Professional role | Team leader/director | 5 (19) |

| Clinician | 22 (81) | |

| Professionalgroup | Clinical nurse | 14 (52) |

| Physiotherapist | 11 (41) | |

| Exercise physiologist | 2 (7) | |

| Years working in allied health | Median: 10 (IQR: 6–17) | |

| Missing/prefer not to say | 6 (22) | |

| Clinical area | Cardiac rehabilitation | 8 (30) |

| Pulmonary rehabilitation | 8 (30) | |

| Both cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation | 11 (40) | |

| Geographic location | Metropolitan Regional/remote | 12 (44) 15 (56) |

n = 27; IQR = interquartile range.

| Position . | Categories . | Count (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female Missing/prefer not to say | 19 (70) 3 (11) |

| Age in years | Median: 47.5 (IQR: 37–53) | |

| Missing/prefer not to say | 5 (19) | |

| Professional role | Team leader/director | 5 (19) |

| Clinician | 22 (81) | |

| Professionalgroup | Clinical nurse | 14 (52) |

| Physiotherapist | 11 (41) | |

| Exercise physiologist | 2 (7) | |

| Years working in allied health | Median: 10 (IQR: 6–17) | |

| Missing/prefer not to say | 6 (22) | |

| Clinical area | Cardiac rehabilitation | 8 (30) |

| Pulmonary rehabilitation | 8 (30) | |

| Both cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation | 11 (40) | |

| Geographic location | Metropolitan Regional/remote | 12 (44) 15 (56) |

| Position . | Categories . | Count (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female Missing/prefer not to say | 19 (70) 3 (11) |

| Age in years | Median: 47.5 (IQR: 37–53) | |

| Missing/prefer not to say | 5 (19) | |

| Professional role | Team leader/director | 5 (19) |

| Clinician | 22 (81) | |

| Professionalgroup | Clinical nurse | 14 (52) |

| Physiotherapist | 11 (41) | |

| Exercise physiologist | 2 (7) | |

| Years working in allied health | Median: 10 (IQR: 6–17) | |

| Missing/prefer not to say | 6 (22) | |

| Clinical area | Cardiac rehabilitation | 8 (30) |

| Pulmonary rehabilitation | 8 (30) | |

| Both cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation | 11 (40) | |

| Geographic location | Metropolitan Regional/remote | 12 (44) 15 (56) |

n = 27; IQR = interquartile range.

Key themes

Analysis of focus group and interview data elicited six main themes: (i) Variable levels of readiness; (ii) Greater telehealth uptake in pulmonary vs. cardiac rehabilitation; (iii) Safety and risk management; (iv) Client willingness—targeted support required; (v) Equity and access; and (vi) New models of care. Each theme and associated subthemes are described in further detail below including example quotes from participants.

Variable levels of readiness

Prior experience

Across services, there was a wide variety of experiences using telehealth, influenced in part by the varying levels that COVID-19 had impacted the services. Some regional services were largely unaffected by COVID-19, whereas metropolitan services were required to stop all in-person care. The maturity of the telehealth service also differed greatly. Two regional services reported no or very limited exposure to telehealth, while one state-wide service had provided telehealth for more than 10 years, and this was considered ‘business as usual’. The presence of telehealth champions (staff that encourage telehealth use and have an enthusiasm for its use) within the service greatly increased the speed with which a service could adopt the new model of care and champions were described as crucial for training and ‘moving others forward’. Adoption was also supported by prior interest in telehealth, with COVID-19 being viewed as a nudge rather than the main reason that a service was utilizing this additional model of care.

‘I don’t think it [COVID-19] was entirely the full reason why we changed, I think we were looking at that anyway, to provide a more flexible model—but I think it [helped us] to include that model.’ (Focus Group 7)

Establishing telehealth services

Many services mentioned that establishing telehealth can be challenging and take time to set up and perfect. Some felt it required approximately 18 months to get the telehealth service working well and ensure all clinicians felt confident using it. The ease of set up was greatly influenced by having good systems and procedures in place including the telehealth system or platform, which needed to be easy to use and ideally also enable opportunities for one-on-one contact with the consumer.

‘… [having] the system set in place has helped a lot—having the [video-conferencing] portal and the virtual waiting room set up for us. So, we can bring patients in individually to [the virtual] clinic and provide that little bit of one-on-one care and make sure that questions are answered prior to our [telehealth] session.’ (Focus Group 7)

Telehealth infrastructure and staffing

Resource issues placed additional pressures on the system and made adopting new innovations challenging. Staffing issues due to recruitment challenges and/or limited funding were particularly prevalent in regional and remote areas where the workforce was more transient and vacant positions were sometimes left unfilled. In other services, the lack of permanent funding for staff was the greatest challenge.

‘Pulmonary rehab has no allocated physiotherapy funding so without that it’s really difficult for us to even explore.’ (Focus Group 4)

Space and the need for dedicated and private telehealth rooms were also common concern for clinicians. Such spaces need to be fitted with appropriate hardware, software, and peripheral devices (e.g. headsets and cameras).

‘So, we need staffing, we need equipment, we'd need a room, as you can see, I’m sitting in a shared office. We don't have a space to actually run something like that.’ (Interview 8)

Greater telehealth uptake in pulmonary vs. cardiac rehabilitation

Programme structure

There was a stark difference in telehealth uptake between cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation. Pulmonary consumers were perceived as more suitable to telehealth models due to the progressive nature of the condition and that these consumers often had greater challenges physically attending in-person (e.g. experiencing shortness of breath walking from the car park to the clinic). Cardiac rehab patients are typically referred to programmes after an acute event, and this appears to create greater anxiety in both consumers and clinicians to be seen in-person, so they could be carefully monitored and have their surgical wounds assessed if required.

‘Clinicians feel more comfortable delivering [pulmonary rehabilitation] at home, whereas in cardiac with a recent event, they feel that they need to have eyes on monitoring [the consumer] at all times.’ (Focus Group 3)

Further, programme formats also influenced telehealth uptake with pulmonary programmes running block-based intake (e.g. all consumers commence the programme together at a first session and complete as a group), which were easier to adapt to telehealth models as compared with rolling programmes (e.g. consumers can commence at any week of the programme and continue until all sessions are complete) that meant constant troubleshooting for new participants who may not be familiar with the format.

‘I think it's probably the way we deliver our programs. So, in our team, pulmonary rehab is a set [block] program whereas cardiac rehab is a rolling program. That was probably the key factor in why it would be very hard to [transition to telehealth in cardiac rehabilitation].’ (Interview 1)

Staff willingness

Some participants also felt that staff willingness played a role in greater reluctance among the cardiac rehabilitation staff cohort. Additionally, financial incentives (e.g. videoconferencing being reimbursed at a higher rate than telephone calls) did not appear to be motivating for cardiac clinicians. And while staff recognized that visual information was helpful for aspects of therapy and/or building rapport, this was not always enough to motivate staff to use videoconferencing.

‘But cardiac just haven't really come on board with [telehealth], but they do certainly deliver, which is frustrating from a management point of view, they deliver a lot of what they call home-based programs with their phone—and they’re just not generating, from my perspective, the same connection, or the same amount of funding.’ (Interview 1)

Safety and risk management

There was a clear need for a risk stratification framework to guide who clinicians offer remotely supervised exercise sessions to and how clinicians can support these consumers to ensure this occurs safely (just as they would for any home-based programme). This was particularly pertinent for consumers based in rural and remote settings where help would be further away if an adverse event occurred; therefore, proximity to emergency care is one aspect that needs to be taken into consideration.

‘Who’s safe? Who are we confident in treating at home in an area where they don’t have direct access to emergency services? So, if you’re next door to the [major tertiary hospital] yes, it's probably really safe—call an ambulance if you’re next door. But out in [rural town] where it's a four or five hour flight back into the city I think we need to be really specific on who we can treat at home and who we really need to see face to face.’ (Interview 6)

To support risk management, clinicians wanted access to real-time objective data for exercise to enable greater remote patient monitoring, thus enabling clinicians to provide more informed exercise prescriptions and coaching and increase clinician confidence. The need for increased monitoring was also requested from consumers who wanted their physiological observations (e.g. blood pressure, heart rate) and other physical aspects (e.g. wound care) regularly monitored to provide reassurance.

‘A lot of them [consumers] came back and said they were concerned that, because they didn't have the face to face they didn't have their blood pressure checked, or they didn’t have the wound—you know—touched, to ensure that it was healing well, and so there’s just a perception about the service [being less high quality]’ (Focus Group 3)

In addition to safety, monitoring was also perceived to improve consumers’ confidence to exercise to their prescribed limit. There was a perception that unmonitored consumers may not exert themselves to the same level.

Client willingness—targeted support required

Some services, mainly located in metropolitan areas, reported limited client interest in telehealth models and a strong preference for in-person care. As described by one interviewee from a metropolitan service ‘…we haven't had more than one client [that] has opted for the virtual [model].’ (Focus Group 3) However, client willingness levels do appear to have improved over time as telehealth has become more familiar and normalized as an alternative model of care.

‘A lot of them are using that sort of format to talk to family overseas … or for their GP consults and things so it's a lot less scary for people and I guess they see that they do get something positive out of it.’ (Focus Group 5)

When well-supported to use telehealth (e.g. provided with technology and troubleshooting support), the feedback from clients was positive.

‘Overall, it was very positive feedback from the patients, I would say that [they] raved about it, they thought it was great [and they] didn’t have to leave their own home, but there was still a delivery of pulmonary rehab to the best of what we could provide in their own home.’ (Interview 2)

There was a need for these positive experiences to be shared with potential clients in the future.

‘I think in rural communities, I think if we can set it up well at the start, and we get good buy in from patients who can then share their experience to other mates that have heart attacks or and can say oh look this works really well, you should give it a go.’ (Interview 6)

Distance and costs

While the benefits for clients were seen across varying services and geographic locations, clients in rural areas had greater incentives due to long travel times to attend in-person programmes. Without telehealth, many of these clients would not have been able to receive rehabilitation at all. However, clinicians in rural areas also reported greater connectivity problems with their consumers. One clinician reported that approximately one-third of their consumers did not have the connectivity to use videoconferencing. The cost of using the internet was also a reported challenge in a particularly low socio-economic area with a clinician reporting one client saying:

‘I would like to continue doing this, but I can't afford to pay for the amount of Internet that it [video-conferencing] uses—it uses all of my plan and I am on the pension…’ (Focus Group 7)

Equity and access

Reaching regional and rural populations

The ability of telehealth to increase the geographical reach of a service was a clear driving force for many clinicians. This was a key reason that clinicians wanted to maintain telehealth options longer-term.

One state-wide service had built-in key performance indicators to ensure their telehealth-delivered service targeted areas of high needs, reporting a required minimum of 45% of their service was being provided to clients outside of South East Queensland.‘[Telehealth] has probably opened our service up to a cohort of patients that previously wouldn't have come in, and ones that we previously wouldn't have done this level of intervention with at home, so I think it's a catalyst to move forward.’ (Focus Group 3)

Reaching special populations

Specific opportunities were also reported for Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations.

However, strategies are required to support clinicians working with these population groups to deliver care in a culturally appropriate way and particularly to build rapport.‘I think a big uncaptured cohort of people are our Aboriginal people in town, who really do not want to come into the hospital. But actually, they do have iPhones. Or if they don’t have iPhones, I could get them to their local clinic and they could sit in front of a computer there. I’m excited that that would work well for them.’ (Interview 7)

‘And we’ve also found that it can be quite difficult to develop rapport with people from Indigenous communities over a screen. Again, there’s some that take to it very well. But a lot struggle with it quite a bit. And when I say struggle, they don’t make eye contact with you, they won't talk—very different from if you can sit in a room and be in the same space.’ (Interview 8)

New models of care

Many services are integrating hybrid models of care (e.g. provide a combination of in-person, telephone, and videoconferencing) with nearly all telehealth-delivered services including an in-person pre- and post-assessment. There is an element of relationship building and rapport that is also supported by in-person care. To overcome limited staff resources, and ensure there are enough client numbers, two services reported pooling resources across a health district and taking turns for clinicians from various facilities to run a telehealth model. This was successful at reducing resource pressures on individual sites.

Providing different options of care was viewed favourably by management. There was also a desire to utilize available staff in rural and remote areas that are not necessarily a part of the cardiac or pulmonary service. For example, one clinician suggested that rural general practitioners or rural physiotherapists could be trained to support clients to set up for a telehealth appointment and facilitate a pre- or post-assessment with virtual support from a specialized clinician.‘I think that the shared care model which we are doing is probably a little bit more novel…because you don’t always have enough numbers to start a group … [but] you’ve got [some] people that have the technology and they're savvy to do it and want to do it. And it’s working—we’re getting the numbers between the two sites in that program and there’s certainly an appetite by services for it not to fall over.’ (Interview 1)

The centralization of education models of care was also something that was favourable to clinicians, particularly those with limited resources and poor access to staff with specialized skills (e.g. dieticians or pharmacists trained in cardiac care). One service also felt that a state-wide self-management programme could reduce unnecessary hospitalizations with greater partnerships between tertiary and primary care. However, this would require better remote monitoring infrastructure.

In order to achieve this, there was a reported need to understand service gaps and know what other services are provided, to identify opportunities that best fit individuals’ needs.‘We would take on the management of them at home and partner with both the hospital and the GPs. [Technology provider] has actually got the capability of doing a dashboard [to show data for each] individual patient. We would do the follow-up calls and some visualization of where they’re at, and then [use] clear escalation pathways either to the GPs or back into the hospital if required.’ (Focus Group 1)

Better quality checks and evaluation of services are also required. Only one service reported having systems in place to provide ongoing quality checks of their telehealth service; this involved a standardized training programme, recording, and feedback of sessions, and ongoing ad hoc quality checks.‘You know we’re doing this re engagement and it's quite difficult to actually find out [from services] what is it that you're offering. We’re very straightforward, this is what we offer you know if it covers lots of areas within Queensland. You have something where everybody inputs that information, so we could just go well, you're not suitable hours, however, there is one X, Y, Z that might be more suitable for you.’ (Focus Group 1)

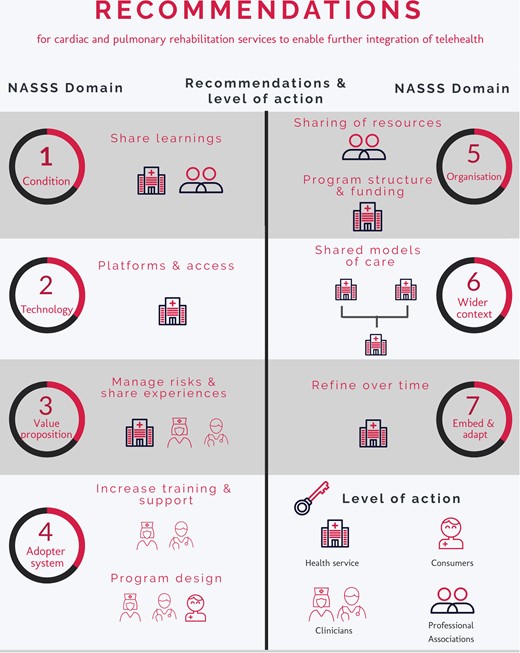

Recommendations

The combined matrix of findings and summarized subthemes was mapped across the NASSS domains to help identify key areas of intervention to support the long-term integration of telehealth into services (Supplementary material online, FileSC). This facilitated the development of recommendations in Figure 1 below (see Supplementary material online, FileSD for an extended version with further details on recommendations).

Recommendations for cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation services to enable further integration of telehealth; NASSS, Non-adoption, Abandonment, Scale-up, Spread, and Sustainability.

The recommendations made for integrating telehealth into cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation services involved actions for a variety of stakeholders, including professional associations, health services, clinicians, and consumers. Professional associations are asked to advocate for better internet access in rural areas as well as assist with developing updated safety protocols and telehealth user guidelines. Health services should improve their platforms, evaluate their services, and use the funding to create permanent staff positions for continuity. Clinicians can look to share their learnings with disciplines outside their own and should participate in training sessions whenever available. Finally, health services and clinicians need to enable consumers to be involved at the very beginning design stages of any service. Further details can be seen in Figure 1.

Discussion

Uptake of telehealth in cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation

We investigated telehealth use and readiness across Queensland among cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation services. At the beginning of the pandemic, many services were using telehealth for the first time and were focused on aspects related to the technology and gaining familiarity with telehealth.13, 14 While some services were still grappling with initial use in our study, the larger conversation regarding ongoing use and sustainability has been much more focused on the value proposition (for clinicians and consumers) for both services.21 Services were weighing up the benefits and opportunities with a clearer understanding that incorporating an additional modality of care can be resource-intensive—requiring time, infrastructure, and additional staff. There was a discrepancy between telehealth use across the two condition groups (pulmonary vs. cardiac). Clinician willingness is a key factor and has long been observed as a key barrier to telehealth uptake.22 The intake format of the programmes (i.e. block vs. rolling) also appeared to influence telehealth uptake across the services. Additionally, the recency and sudden nature of an acute coronary event also appear to reduce clinician and consumer confidence in exercising remotely. This body of work has facilitated sharing of lessons across the cardiac and pulmonary state-wide networks, and the development of a toolkit for pulmonary rehabilitation is now being adapted for cardiac and heart failure rehabilitation services and guidelines have recently been published.23

Perceived value of telehealth

The clearest value of telehealth was for services covering large geographic areas, where effort and costs are offset by savings in travel time for both consumers and staff.24–27 This is supported by the literature which suggests that while many services believe delivering care via telehealth may be cheaper than in-person, it is often not the case; telehealth is often an investment to enable consumer choice and provide greater flexibility in how and where care is received.28 According to Snoswell et al.,28 the greatest potential for cost savings is likely to be due to productivity gains, telementoring (e.g. staff upskilling), and reduction in secondary care.28 For cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation services, the greatest potential for health service savings lies in extending the service reach and increasing participation in cohorts that previously would have declined rehabilitation options altogether, thereby, potentially reducing future cardiovascular events.29 However, services require greater reassurance that public health funding will be available to support the cost if there are increased staff requirements.

Future possibilities, increased inclusion, and sustainability challenges

As telehealth funding streams are not well established, models of care that pool resources across services may help to increase sustainability by spreading costs across larger numbers of participants, either at a small scale (e.g. 2–3 services) or across the state. Telehealth enables new opportunities for resource efficiencies that are not possible, or at least impractical, for centre-based delivery. Wade and Stocks (2017) summarize in a review paper the growing evidence that telehealth can reduce inequalities in cardiovascular outcomes in Australia among disadvantaged groups such as those living in rural locations, from low socio-economic backgrounds, and/or First Nations communities.30 However, greater action and resources are required to ensure the development and delivery of secondary prevention programmes (both in-person and telehealth) are appropriate for these population groups.31 Currently, there are low levels of involvement in First Nations peoples in these programmes and limited cultural understanding of staff designing and delivering the programmes.32 Telehealth also has the opportunity to reduce staffing pressures across services that have notorious challenges attracting and retaining staff, especially in rural and regional areas where resources are often scarce, and having enough funded staff time to provide multidisciplinary care given the wide range of expertise required to support cardiac and pulmonary services (e.g. nursing, physiotherapy, pharmacy, dietetics, occupational therapy, etc.). Smaller rural and regional services often do not have the resources to provide multiple modalities of care to their clients, nor the speciality expertise which is often more abundant in metropolitan areas. However, they welcome the opportunity for their clients to be able to log in to educational sessions happening in major hub sites or additional exercise training sessions that may occur virtually.

Safety and effectiveness concerns

There were clear concerns from clinicians regarding the safety of providing exercise sessions to high-risk individuals and to those that live a long way from emergency support. Standardized risk and mitigation policies and action plans are required to assist in reducing these concerns. Some services do have these policies in place, but this needs to be more broadly implemented and may require adaptation to consider specific requirements for remotely delivered exercise. While safety was a common concern, it should be interpreted within the context of current practice, where home programmes are often provided without any supervision and the health risks of sedentary behaviour are often greater than the risk of an adverse event occurring due to exercise. Clinical trials that include remotely supervised exercise have to date shown that the risk of adverse events is very low.33–35 Remote patient monitoring can quantify and/or qualify how participants respond to exercise stress. This can help clients feel more confident to exercise at appropriate levels36 and may also reassure clinicians. Remote patient monitoring is an underutilized option for enabling greater objective measurement and supervision of clients exercising remotely. A meta-analysis of multiple studies demonstrated the safe and effective use of remote monitoring within the cardiac rehabilitation population.37 A major challenge has been implementing remote monitoring solutions into clinical practice and setting up seamless interoperable systems that work within current health systems.38

Evaluations of ‘real-world’ telehealth models need to be conducted to ensure equivalent programme quality and effectiveness. Additionally, most services wish to maintain some aspect of in-person care, a viewpoint that was also observed in previous qualitative research.39 Currently, in-person models are viewed as ‘gold standard’ by many clinicians and consumers. However, this perception contradicts growing evidence showing telehealth can be at least as effective for improving health and well-being,10, 35, 37, 40 and overlooks opportunities to help many people who receive no rehabilitation at all because they are unable or unwilling to attend in-person programmes.41

Strengths and limitations

This study was conducted across Queensland and, therefore, may not be generalizable across other jurisdictions. In particular, it should be noted that there is a high heterogeneity of cardiac rehabilitation programme structure in Australia.42 Further, we only interviewed public services and the experience may have been different in private rehabilitation services. However, public services make up the majority of cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation care in Queensland. The study was strengthened by the inclusion of participants working across metropolitan, regional, and rural/remote services, and by being able to compare the experience across two clinical cohorts (cardiac and pulmonary) as well as both high and low users of telehealth. We also had a strong response rate and were able to reach data saturation including multidisciplinary participants reflective of the staffing of both cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation services. Additionally, our hybrid inductive/deductive framework analysis adds rigour to the data analysis as we were able to capture the most salient aspects of each participant’s telehealth experiences, while also mapping these against an established framework appropriate for guiding future adoption and sustainability. This ensures our findings provide a meaningful contribution to progress telehealth rehabilitation programmes.

Conclusion

As we move into a new phase of the pandemic which involves adapting to delivering care alongside managing COVID-19, new strategic directions are required to determine how telehealth can be sustainably embedded into secondary prevention services to maximize overall reach and participation. Services that wish to maintain telehealth require support to ensure the infrastructure, workforce, and funding schemes can sustain these models of care long-term. There are clear opportunities for programmes that service large geographic areas and opportunities to increase programme participation rates more broadly, especially among hard-to-reach population groups. To increase sustainability, sharing of limited staff resources through more centralized models of care should be explored. Further, the adaptation of current risk stratification processes and greater implementation of remote patient monitoring are required to enhance consumer and staff confidence about the safety of remotely supervised exercise. Lastly, greater information regarding what services are provided across the state is required to determine service gaps and to target telehealth modalities to areas with large consumer needs and limited staff capacity. These findings have been combined into clear recommendations that we hope will support similar services (inter)nationally to further integrate telehealth modalities where appropriate.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing online

Funding

E.E.T. (105215), S.C. (104860), and J.R. (102585) were funded by fellowships from the National Heart Foundation of Australia during this project.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Author notes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Comments