-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Germana Panattoni, Luca Monzo, Maria Gugliotta, Giulia Proietti, Mario Tatangelo, Ilaria Jacomelli, Giuseppe Zimbardo, Federica Meringolo, Elisa Fedele, Leonardo Calò, Optimal management of patients after acute coronary syndrome, European Heart Journal Supplements, Volume 25, Issue Supplement_C, May 2023, Pages C84–C89, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartjsupp/suad039

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Patients with clinically established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease are at a very high risk of recurrent cardiovascular events. An adequate management of risk factors and the implementation of healthy behaviours significantly decrease the risk of unfavourable clinical outcomes and future cardiovascular events, including death. Patients discharged after an acute coronary syndrome should be managed according to their individual risk level in order to ensure the appropriate treatment. Nevertheless, care pathways should also take into consideration the available resources and the logistical/structural aspects. In this setting, cardiac rehabilitation is prosed as a multidisciplinary approach to improving daily function and reducing cardiovascular risk factors. The organization of a network with the involvement of different medical and non-medical figures is essential to ensure successful outcomes and expected cost-effectiveness.

General considerations

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), which include coronary heart disease and stroke, are the most common fatal non-communicable diseases globally, responsible for an estimated 18.6 million deaths in 2019. Individuals with a prior cardiovascular event have a risk 5 times greater to have another event than people without known CVD. Patients with clinically established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) are at very high risk of recurrent CVD events.1 An adequate management of risk factors and the implementation of healthy behaviours (including smoking cessation, recommended physical activity, a healthy diet, and maintaining a physiologic weight) significantly decrease the risk of unfavourable clinical outcomes and future cardiovascular events, including death. The World Health Organization estimates that 75% of cardiovascular mortality can be reduced with appropriate changes in lifestyle.

After acute coronary syndrome (ACS) adherence to antithrombotic treatment and to other drug therapies (renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system blockers, betablockers, and statins) is a priority. Less is known about the adherence to behavioural recommendations and the benefit that comes from lifestyle modification. Patients discharged after ACS should be directed to care pathways appropriate to their individual risk level in order to ensure appropriate patient management. An encouragement to healthy behaviours in the immediate post-event phase should be given as high a priority and programmes that encourage early lifestyle modification and secondary prevention should be perform and justify a significant investment.

The EUROASPIRE (European Action on Secondary and Primary Prevention by Intervention to Reduce Events) V survey2 showed that the majority of patients with coronary artery diseases (CADs) failed to achieve the lifestyle, blood pressure, lipid, and glycemic targets.

In this regard, current guidelines support the use of cardiac rehabilitation (CR) (Class I, level of evidence A)1 in patients after ACS and recommend the referral of patients after myocardial infarction (MI) to CR. Indeed, recent studies have demonstrated the role of CR in improving clinical outcomes, quality of life, and in reducing hospital admissions and mortality.3

Cardiac rehabilitation is a multidisciplinary intervention, whose core components are well recognized, including patient assessment, management and control of cardiovascular risk factors, physical activity counselling, prescription of exercise training, dietary advice, psychosocial management, and vocational support. The overall goals focus on optimizing the management of cardiovascular risk factors.4 Indispensable for profit from these facilities are a recoverable clinical, functional, and cognitive condition.

The shared management protocol of the post-acute phase is an indispensable condition for secondary prevention/rehabilitation programmes. All the actors, cardiologists, nurses, and general practitioners should be involved synergistically. The discharge represents a fundamentally important cornerstone for the care of patients and their follow-up.

Care process after acute coronary syndrome

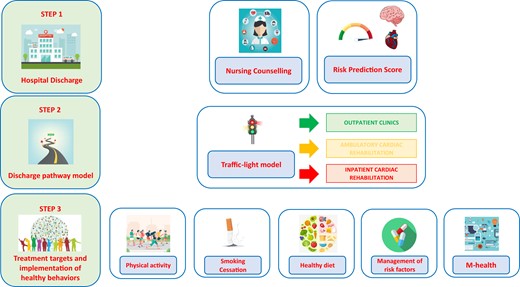

Care process after ACS should include three indispensable steps (Figure 1):

Hospital discharge.

Discharge pathway models.

Treatment targets and implementation of healthy behaviours.

Step 1: hospital discharge

The discharge represents a fundamentally important cornerstone for the management of patient. In this step, primary care providers should play an important role in the education support of post-ACS patients, as part of the overall strategy to improve risk factors control. A counselling activities should be provided to patients after ACS to ensure a significant positive impact on the health and quality of life for the patients and families.

According to American and European guidelines,1,5 patients with clinical manifest atherosclerosis have 20% or more absolute 10-year risk of developing recurrent vascular events, such as cardiovascular death, ischaemic stroke, or MI.

The 10-year risk of cardiovascular events is not the same for all patients and ranges widely across risk classes (from <10% to 30%). The identification of high-risk patients using risk stratification tool is mandatory to prevent recurrent events, to engage intensive treatments and follow-up strategies. The achievement of the risk factor targeted represents an opportunity for major public health gain but preventive treatments may not be indicated for all patients.

Risk stratification tools to predict long-term risk of developing recurrent vascular events include the SMART (Secondary Manifestations of Arterial Disease) risk score6 and the European Action on Secondary and Primary Prevention by Intervention to Reduce Events (EUROASPIRE) risk model.7

The SMART risk score estimates the 10-year risk for MI, stroke, or vascular death.6 This score was developed in the Netherlands in a population of 5788 individuals with previous CVD (including CAD, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral artery disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and polyvascular disease), enrolled in the SMART-study,8 and externally validated in three different cohorts.9 The variables included in the risk score model are age, sex, current smoking, diabetes, blood pressure, cholesterol, CAD, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral artery disease, creatinine, and high sensitivity C-reactive protein values.

The EUROASPIRE Risk Calculator7 estimates the 2-year risk of recurrent CVD in patients with stable CAD. Data were available for 12 484 patients after a median follow-up time of 1.7 years. The association between potential risk factors and the incidence of the primary endpoint [a composite of fatal CVD or new hospitalizations for non-fatal MI, stroke, heart failure (HF), coronary artery bypass graft, or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)] was evaluated on data from 8000 randomly selected patients and was then validated in the remaining 4484 patients.

Step 2: discharge pathway model

As reported in recent studies,10,11 there has been a progressive reduction in hospital mortality compared with an increase in post-discharge mortality for patients with ACS.

An important role in this trend seems to have the lack of appropriate post-discharge cardiological care pathways, based on individual post-ACS risk.

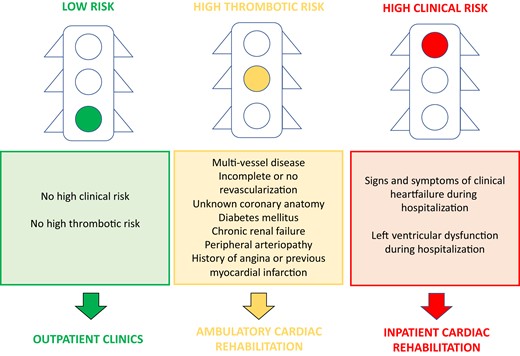

An Italian Consensus Document12 provides a joint proposal for the management of patients hospitalized for ACS and delineate three types of care pathways according to the estimated risk of clinical events (Figure 2) that can be represented as ‘a traffic light’ model:

patient at high risk for HF and/or left ventricular dysfunction;

patient at high thrombotic risk;

low-risk patient.

Features of patient at high risk for heart failure and/or left ventricular dysfunction

Killip class.

Left ventricular ejection fraction <40%.

Left ventricular ejection fraction in a range between 40% and 45% with restrictive diastolic filling pattern, significative mitral valve regurgitation, elevated wall motion score index, and non-dilated ventricle.

Important variation of B-type natriuretic peptide.

Use of loop diuretics.

Left ventricular dysfunction and the presence of signs or symptoms of HF represent the more suitable variables to perform a prognostic stratification and to delineate specific discharge pathways. The onset of HF during hospitalization and after discharge is an important predictor of mortality during follow-up.13 Previous studies have demonstrated the direct correlation between cardiac remodelling and worsening prognosis, indicating as predictive variables the diastolic filling pressure and the presence of mitral valve regurgitation.

In this setting of HF, inpatient CR (residential) centres, individually tailored to the needs of patients, may be preferred to provide a comprehensive multidisciplinary programme in order to reduce the risk of ventricular remodelling and consequently cardiovascular hospitalizations and mortality.4 A recent review14 showed that CR provides important advantages, including reduced risk of MI, a small reduction in all-cause mortality and a large reduction in all-cause hospitalization, along with associated healthcare costs, and improved quality of life up to 12 months’ follow-up.15 Over longer-term follow-up, benefits may include reductions in cardiovascular mortality and MI. Despite the proven benefit, according to the EUROASPIRE V registry2 the attendance rate for these programmes is 34%. This situation has worsened as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. A possible alternative could be offered by telerehabilitation that has shown to be at least equally beneficial and cost-effective than centre-based CR but overcomes some barriers of traditional hospital rehabilitation, especially during a pandemic situation.16

Features of patient at high thrombotic risk

Peripheral arteriopathy.

History of angina or previous MI.

Multi-vessel coronary heart disease.

Incomplete revascularization.

Non-revascularized patients.

Patients with high ischaemic risk have an elevated risk of developing recurrent vascular events. For such patients, outpatient CR should be provided with frequent contacts and programmes suited to the clinical status. If it is not available, the care pathway should take place in cardiological clinics of intensive secondary prevention with nursing counselling, anti-smoking programmes, assessment of therapeutic adherence, dietary consultations, prescription of physical exercise, and psychological support.

Features of low-risk patients

Patients without HF and/or left ventricular and high thrombotic risk should be addressed to a low-intensity follow-up pathways, with a single cardiac visit in the first year and subsequent referral to the general practitioner. Indications for secondary prevention must also be provided in the discharge letter, through dedicated counselling and with remote follow-up.

Step 3: treatment targets and implementation of healthy behaviours

Smoking cessation

Smoking cessation after ACS is a major challenge in secondary prevention, especially in patients <50 years, where 56% of men and 46% of women are persistent smokers.2 In patients with CAD, the significant risk reduction achievable through smoking cessation provides a strong motivation to continue and intensify efforts in this direction. It should, therefore, be kept in mind that the risk of a coronary event in ex-smokers decreases rapidly after quitting and is similar to the risk for non-smokers within 2–3 years.17 Patient and family members should be sensitized to a smoking cessation intervention. The goal must be the complete abolition of cigarette smoking and the prevention of exposure to environmental smoke. This behavioural approach should include an assessment of smoking status and willingness to quit at each visit. The patient should be encouraged to quit and effective treatment intervention offered through social support, special programmes or pharmacotherapy. A useful strategy for achieving effective smoking cessation is the ‘5 A’ strategy1 (Table 1).

| ‘5 A’ strategy . | . |

|---|---|

| Ask | Acknowledge all smokers at each visit (enter smoking data in history collection). |

| Advise | Send a strong, clear, and personalized message, convincing every smoker to quit. |

| Assess | Assess willingness to quit smoking at each visit. |

| Assist | Advise the patient to develop a plan including a quit date, identify sources of help to quit smoking among family and friends, eliminate sources of failure from the environment. Provide advice, educational materials, and suggest behavioural interventions. Advise the use of drug therapy with varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine. |

| Arrange | Meet with the patient shortly after cessation to assess the success of the intervention. If unsuccessful, identify obstacles, and solutions. |

| ‘5 A’ strategy . | . |

|---|---|

| Ask | Acknowledge all smokers at each visit (enter smoking data in history collection). |

| Advise | Send a strong, clear, and personalized message, convincing every smoker to quit. |

| Assess | Assess willingness to quit smoking at each visit. |

| Assist | Advise the patient to develop a plan including a quit date, identify sources of help to quit smoking among family and friends, eliminate sources of failure from the environment. Provide advice, educational materials, and suggest behavioural interventions. Advise the use of drug therapy with varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine. |

| Arrange | Meet with the patient shortly after cessation to assess the success of the intervention. If unsuccessful, identify obstacles, and solutions. |

| ‘5 A’ strategy . | . |

|---|---|

| Ask | Acknowledge all smokers at each visit (enter smoking data in history collection). |

| Advise | Send a strong, clear, and personalized message, convincing every smoker to quit. |

| Assess | Assess willingness to quit smoking at each visit. |

| Assist | Advise the patient to develop a plan including a quit date, identify sources of help to quit smoking among family and friends, eliminate sources of failure from the environment. Provide advice, educational materials, and suggest behavioural interventions. Advise the use of drug therapy with varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine. |

| Arrange | Meet with the patient shortly after cessation to assess the success of the intervention. If unsuccessful, identify obstacles, and solutions. |

| ‘5 A’ strategy . | . |

|---|---|

| Ask | Acknowledge all smokers at each visit (enter smoking data in history collection). |

| Advise | Send a strong, clear, and personalized message, convincing every smoker to quit. |

| Assess | Assess willingness to quit smoking at each visit. |

| Assist | Advise the patient to develop a plan including a quit date, identify sources of help to quit smoking among family and friends, eliminate sources of failure from the environment. Provide advice, educational materials, and suggest behavioural interventions. Advise the use of drug therapy with varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine. |

| Arrange | Meet with the patient shortly after cessation to assess the success of the intervention. If unsuccessful, identify obstacles, and solutions. |

It is possible to evaluate ‘bridge’ strategies, to achieve the goal of complete cessation of cigarette smoking, through the use of electronic cigarettes. The use of these devices is probably more effective than typical nicotine-based treatments (patches, gum, etc.) in achieving smoking cessation. However, the long-term effect on lung function and CVDs of these devices is still being studied.18

Physical activity

Two-thirds of patients did not achieve the suggested physical activity target.2 An individualized approach should begin during hospitalization and the objectives of the physical activity should be defined within the patient's overall treatment plan. Physical activity should begin as early as 12 h after an acute event, including joint movement and postural changes. In fact simple exposure to orthostatic or gravitational stress reduces much of the decline in physical performance.19 At the time of discharge, the patient should demonstrate an understanding of motor activities that may be inappropriate or excessive. A tailored programme should be initiated early after the patient’s discharge and be aimed at designing an exercise programme based on frequency–intensity–time–progression characteristics and risk profile of patient. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing should be performed in all patients for a correct prescription of tailored exercises, since the ventilatory thresholds allow to define the intensity of the exercise in a highly individualized way. If the cardiopulmonary test is not available, a 6-min walking test associated with the terminal evaluation of perceived effort using the Borg scale is a useful tool for the clinician in prescribing exercise.20,21 Subsequent check-ups should be based on the evaluation of the patient’s adherence to the prescribed exercise plan and they should include a brief motivational interview and a complete functional assessment to quantify progresses and readjust the exercise plan based on the needs.

Hypertension

Blood pressure (BP) measurement, with a target of 130/80 mmHg is a strongly secondary prevention recommendation after ACS.1 Of patients prescribed drugs to lower their blood pressure 54% were at target and 76% reported complete adherence with the intake of their blood pressure-lowering drugs.2

Treatment targets and goals: towards intensive lipid-lowering regimens and tailored care

In post-ACS patients, an LDL-C-reduction of ≥50% from baseline and an LDL-C goal of <55 mg/dL are recommended. For patients with CVD who experience a second vascular event within 2 years despite maximally tolerated statin-based therapy, an LDL-C goal <40 mg/dL may be considered.22 Despite the acknowledged clinical benefits of lowering LDL-C in patients with ACS, attainment of LDL-C target values remains suboptimal in this very high-risk setting. In EUROASPIRE V registry,2 lipid-lowering drugs were prescribed to 84% of patients, but only 76% reported an acceptable therapeutic compliance. According to current dyslipidaemia guidelines22 the approach to obtain therapeutic targets was the stepwise strategy, based on the prescription of a high-intensity statin up to the highest tolerated dose and a combination with ezetimibe or an addition of a PCSK9 inhibitor after 4–6 weeks if the goals are not achieved. However, this strategy needs for intermediate clinical and laboratory checks and it is time-consuming. It is mandatory, that all very high-and extremely high-risk patients must be treated with combination therapy as the basic standard of care, as early as possible.23

Glycemic target

It is recommended evaluate glycemic blood levels in all patients with ACS upon the hospital admission, regardless of a history of diabetes. Glycemic levels should be also frequently monitored in patients with overt diabetes or hyperglycemia on admission.

Diet and weight management

A healthy diet is an important component of secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Current guidelines recommend a regular intake of fruits and vegetables, wholegrains, and fish, a moderate consumption of nuts, to limit saturated fats to <10% of total intake, and alcohol consumption <100 g/week or 15 g/day.24 The Mediterranean diet and the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet have been shown, promoting intake of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, nuts, fish, vegetable, and olive oils, to prevent major cardiovascular events and sudden cardiac death, and to reduce cardiovascular risk.1 Healthy diets with energy intake limited to the amount needed to obtain and maintain a healthy weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2), and increasing physical activity, are recommended for weight management after ACS.

Follow-up

After revascularization and/or after stabilized ACS (<1 year), patients should be strictly monitored due to increased recurrence rate. Current ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes recommend24 to reassess left ventricular function 8–12 weeks after the revascularization procedure to evaluate the improvement of cardiac function (myocardial stunning or hibernation) or possible deterioration given by concomitant CVDs. One year after revascularization, even if the patient is asymptomatic, an annual evaluation with a 12 lead ECG, is warranted to evaluate clinical status, medication compliance adherence to targets of cardiovascular risk factors. A non-invasive stress test imaging to assess for silent ischaemia and a transthoracic echocardiography should be performed every 3–5 years. Laboratory tests (lipid profile, renal function, a complete blood count, glycaemia status, biomarkers, etc.) should be reassessed periodically.

Mobile health in secondary prevention post-acute coronary syndrome

The current number of mobile phone users is 7.26 billion, meaning 91% of the world’s population owns a mobile phone. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Observatory for eHealth defined mobile Health (mHealth) as medical and public health practice supported by mobile devices, such as mobile phones, patient monitoring devices, personal digital assistants, and other wireless devices.25 mHealth tools included text messages, Bluetooth-enabled electronic pill boxes, online messaging platforms, and interactive voice calls. Individualized mHealth-based interventions and real-time feedbacks represented a promising tool for facilitating adherence to health behaviours and medications, reminding issue medical appointment, and generating notifications for CVD monitoring,26 especially during a period of lockdown and restricted social mobility due to the COVID-19 pandemic.16 Several studies have reviewed the use of mHealth as a powerful tool and have demonstrated the effectiveness of mHealth on smoking, physical activity, weight loss, and blood pressure-lowering intervention in patients with CVD.27,28

Despite the promising results, there is insufficient evidence to draw definite conclusions and the role of support prevention programmes remains uncertain, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. The TEXTMEDS intervention (Text Messages to Improve Medication Adherence and Secondary Prevention After Acute Coronary Syndrome)29 examined the effects of text message-delivered cardiac education and support on medication adherence after an ACS, demonstrating that a text message-based programme had no effect on medical adherence but small effects on lifestyle risk factors. Further research is required to evaluate mHealth-based interventions benefits in patients after hospitalization for ACS.

Conclusion

Optimal management of post-ACS patients involves programmes of secondary prevention and CR in the context of a structured post-acute network. Cardiologists, non-medical health professionals—mainly nurses—and general practitioners are all equally involved in the care pathway. A strict cardiovascular risk factors management and encouragement of healthy behaviours in the immediate post-event care of patients with ACS should be regarded as the highest priority. The care network organization should consider the needs of the patient and caregivers, together with the available economic resources and the logistics. The delivery of a comprehensive programme is essential to ensure significant beneficial effects on outcomes and at a favourable cost-effectiveness.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this research.

References

Author notes

Conflict of interest: None declared.