-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Salvatore Brugaletta, William Wijns, Personalized vascular care: Why it is important?, European Heart Journal Supplements, Volume 24, Issue Supplement_H, November 2022, Pages H1–H2, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartjsupp/suac051

Close - Share Icon Share

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide. Its burden is estimated to grow further in the future, due to rapidly aging of global population and the explosion of cardiovascular risk factors, such as diabetes, dyslipidaemia, and obesity.1

The aim of global healthcare system is to contain such expansion, by providing medical doctors the right tools for educating people in primary and secondary prevention and for selecting the right care, customized per each patient. However, specifically looking at the healthcare system of each country, we may face different barriers. Each country, for example, differ on how patients may access to healthcare and how patients are involved in their own healthcare. Moreover, healthcare systems tend to put much attention to a specific intervention, device, or to a specific healthcare action rather than to optimize care across the entire patient journey, considering not only the intervention per se but also the time before (e.g. primary prevention) or after (e.g. secondary prevention). Such lack of personalization in healthcare involves not only patients but also physicians who are overload of administrative tasks with limited time to spend with patients and administrators, pressured to reduce costs. During the last 2 years, the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened this condition, further diminishing patients experiences and involvement in their own healthcare, with potentially poorer outcomes and higher cost for society.2

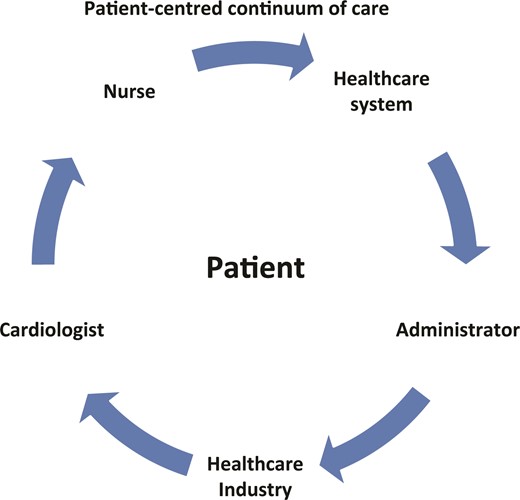

Given this fragmentated background and the increasing burden of vascular disease in the coming years, the need for personalized vascular care is very much needed because it is the road to obtain optimal outcomes by implementing a patient-centred continuum of care, prior, during and after the intervention (Figure 1). Patients’ desire for personalized and tailored care could challenge healthcare administrators to rethink the one-size-fits-all programme designed to control costs, delivering more valuable programme by looking beyond the intervention. The ultimate goal for all stakeholders should be improving patient experiences, outcomes, and value throughout the care continuum.

Personalized health care should be centred to the patient. The various health care providers should collaborate each other.

To fill these gaps and deliver maximum value, an integrated care solution that can manage products and services across the entire patient journey—not just at the point of an intervention—should be created. As such, healthcare systems should emphasize delivering wellness to patients above all else. Such approach may provide mutual benefits for all the actors of the healthcare process: the doctors may provide the best care for their patients, by increasing their adherence to treatment and lifestyle modifications, where healthcare systems and industries may share and facilitate their vision in providing the best healthcare possible. In the digital era we are living, costs for making it possible are not elevated and a small inversion may contribute to a significant improvement in outcome and reduction in cost of outcomes.

Thinking on how to develop a personalized vascular care, we have three different options (Table 1). First one was developed in Boston through the International Consortium for Health Outcome Measurement (ICHOM). It is a business approach, insisting on accountability of care, focused on the development and validation of patient-related outcome metrics. The second one comes from California, it is focused on new technology, such as sensors, telemedicine, artificial intelligence, aiming to provide patient and doctor with data timely accessible; they insist on the reconstruction of healthcare to make it more patient-centric. What we do—as cardiologist—is to integrate these two options in a Hippocratic legacy, allowing us to remaining health care professionals delivering the best care as possible and give us enough time to deliver compassionate care to our patients. Of note, all these three options are complementary.

| . | What? . | How? . |

|---|---|---|

| ICHOM | Business-driven | Accountability |

| PROM’s | ||

| California (Stanford, San Diego) | Technology-driven | Telemedicine |

| Patient empowerment | ||

| Timely data access | ||

| Our community | Hippocratic legacy | Act as healthcare professionals |

| Compassionate care givers |

| . | What? . | How? . |

|---|---|---|

| ICHOM | Business-driven | Accountability |

| PROM’s | ||

| California (Stanford, San Diego) | Technology-driven | Telemedicine |

| Patient empowerment | ||

| Timely data access | ||

| Our community | Hippocratic legacy | Act as healthcare professionals |

| Compassionate care givers |

| . | What? . | How? . |

|---|---|---|

| ICHOM | Business-driven | Accountability |

| PROM’s | ||

| California (Stanford, San Diego) | Technology-driven | Telemedicine |

| Patient empowerment | ||

| Timely data access | ||

| Our community | Hippocratic legacy | Act as healthcare professionals |

| Compassionate care givers |

| . | What? . | How? . |

|---|---|---|

| ICHOM | Business-driven | Accountability |

| PROM’s | ||

| California (Stanford, San Diego) | Technology-driven | Telemedicine |

| Patient empowerment | ||

| Timely data access | ||

| Our community | Hippocratic legacy | Act as healthcare professionals |

| Compassionate care givers |

At the time to translate in practice this personalized vascular healthcare, it should comprise various elements. We need more face-to-face interaction and time of quality between doctors and patients: this step is much important to make the patients feeling confident that all theirs concerns are being considered. Of note, patients carry the burden of disease and they request us not only to be professionals but also to be care givers and to help them carry the burden of disease. In a two-way patient–doctor relationship, the patient plays an active role in shared decision-making, as this is the way to increase h@s compliance to the treatment proposed, including modification of lifestyle. The doctor should be able to review relevant data pertaining to success achieved with similar patients in order to elaborate an individualized treatment plan. The role occupied by computer or smart application is crucial, as they may allow an effective information-sharing between care provider, hospital specialists, and patients. Technology can help physicians to obtain all necessary information/date timelier and deliver a higher standard of care through tailored treatment. This data sharing is bidirectional, allowing on one side doctors to provide treatment information to patients and on the other side patients to provide doctors feedback about their symptoms. Such ability for the doctor to monitor the patient’s progress remotely and continuously, picking up early warning signs of deterioration with consequent adjustment in the treatment, is crucial for personalized vascular care.

The COVID-19 pandemic by accelerating the need for personalized care and telemedicine has given us the chance to practice medicine virtually as never before. Telemedicine has proven a couple of very positive concepts. Patients can now get more involved in their self-assessment during virtual office visits thanks to new medical devices available on the market. The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed how physicians may use app and data to overcome the challenges of not being able to see the patient face-to-face.

In this supplement of European Heart Journal, we see how personalized vascular healthcare is much needed (ref. West) and how it can be delivered in the best way.

A personalized healthcare approach may improve satisfaction and outcomes in ischemia without obstructive coronary artery disease patients (ref. Angela Maas article). The innovative combination of physical activity monitors and a tailored app has shown promising results in delivering with better results cardiac rehabilitation in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (ref. Davies Article). In this regard, wearables data could be integrated to hospital technologies in order to be used by doctors for providing a patient-centred care (ref. paper Hung).

Remote digital smart devices may be also used in personalizing heart failure management (ref. Adamson) or in clinical trials, for measuring response to specific therapy by using subjective scales: Ganesananthan et al. will present us their experience in clinical trials, such as ORBITA-2, ORBITA-STAR, and ORBITA-COSMIC (ref. Rasha Al-Lamee). Eventually we have the industry’s point of view about the future of personalized vascular care (ref. West).

As high-level healthcare providers, we need to look beyond a specific invasive intervention by implementing new technologies to have again the patient at the centre of healthcare: people do not just want to feel cared for, they want to feel cared for on an individual level.

Funding

This paper was published as part of a supplement sponsored by Abbott.

Data availability

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this research.

References

Author notes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

- aging

- dyslipidemias

- obesity

- physical activity

- primary prevention

- percutaneous coronary intervention

- ischemia

- coronary arteriosclerosis

- cardiovascular diseases

- patient compliance

- diabetes mellitus

- cardiac rehabilitation

- cardiologists

- artificial intelligence

- seizures

- heart disease risk factors

- vascular diseases

- heart failure

- diabetes mellitus, type 2

- caregivers

- cause of death

- computers

- continuity of patient care

- cost of illness

- explosions

- feedback

- health

- health personnel

- office visits

- patient-centered care

- reconstructive surgical procedures

- self assessment

- technology

- telemedicine

- vision

- heart

- orbit

- teaching

- secondary prevention

- lifestyle changes

- health outcomes

- health care systems

- medical devices

- care plan

- integrated treatment

- community

- standard of care

- accountability

- medical tourism

- sensor

- shared decision making

- empowerment

- weight measurement scales

- information sharing

- feelings

- data sharing

- coronavirus pandemic