-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Roberto Caporale, Giovanna Geraci, Michele Massimo Gulizia, Mauro Borzi, Furio Colivicchi, A. Menozzi, Giuseppe Musumeci, Marino Scherillo, Antonietta Ledda, Giuseppe Tarantini, Piersilvio Gerometta, Giancarlo Casolo, Dario Formigli, Francesco Romeo, Roberto Di Bartolomeo, Consensus Document of the Italian Association of Hospital Cardiologists (ANMCO), Italian Society of Cardiology (SIC), Italian Association of Interventional Cardiology (SICI-GISE) and Italian Society of Cardiac Surgery (SICCH): clinical approach to pharmacologic pre-treatment for patients undergoing myocardial revascularization procedures, European Heart Journal Supplements, Volume 19, Issue suppl_D, May 2017, Pages D151–D162, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/sux010

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The wide availability of effective drugs in reducing cardiovascular events together with the use of myocardial revascularization has greatly improved the prognosis of patients with coronary artery disease. The combination of antithrombotic drugs to be administered before the knowledge of the coronary anatomy and before the consequent therapeutic strategies, can allow to anticipate optimal treatment, but can also expose the patients at risk of bleeding that, especially in acute coronary syndromes, can significantly weigh on their prognosis, even more than the expected theoretical benefit. In non ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes patients in particular, we propose a ‘selective pre-treatment’ with P2Y12 inhibitors, based on the ischaemic risk, on the bleeding risk and on the time scheduled for the execution of coronary angiography. Much of the problems concerning this issue would be resolved by an early access to coronary angiography, particularly for patients at higher ischaemic and bleeding risk.

Revised by Antonio Francesco Amico. Matteo Cassin, Emilio Di Lorenzo, Luciano Moretti, Alessandro Parolari, Emanuela Pccaluga, Paolo Rubartelli

Consensus Document Approval Faculty in appendix

Introduction

The great efficacy in the treatment of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and coronary disease in general, can be attributed to the diffusion of myocardial revascularization by both percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), and to the availability of antithrombotic drugs that effectively reduce ischaemic complications. It is a widespread practice to administer antiplatelet and/or anticoagulant therapy before performing coronary angiography (a strategy known as ‘pre-treatment’) in order to prevent ischaemic events before a revascularization procedure and to reduce peri-procedural infarction in case of PCI. Pre-treatment may however, expose the patient to haemorrhagic complications without providing any benefit in case of low ischaemic risk, or require its rapid discontinuation in case of surgical revascularization. Pre-treatment may furthermore provide very different theoretical benefits according to the patient's clinical conditions, as they could be greater in acute syndromes, where the instability of the atherosclerotic plaque and thrombosis prevail.

The choice of the drugs to be administered before invasive intervention is made more complex since the last European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on non ST-segment elevation (NSTE) ACS1 state that patients with ischaemia-induced troponin elevation, who are defined as being at high risk, should be referred for a coronary angiography within 24 h; something that actually occurs in a minority of patients.

This consensus document, which was drawn up by experts from the leading Italian societies of cardiology, aims to provide an instrument to guide the choice of treatments as well-suited as possible to the clinical condition of patients candidates to myocardial revascularization.

Suggested options are summarized in tables reported at the end of every chapter. The weight of the recommendations is shown on a coloured scale: the recommended treatment appears in green; the optional treatment for which a favourable opinion prevails appears in yellow; a treatment that is possible, but only in selected cases is in orange whereas contraindicated treatments are in the red column.

ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome

Antiplatelet drugs

Oral antiplatelet agents

Pre-treatment with aspirin is recommended in all ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (STE ACS) patients’ candidates for PCI, but no specific data are available in the literature.2

In patients with STE ACS, angioplasty is usually performed within a few hours or minutes, making difficult to effectively inhibit platelets hyperactivity by oral agents, given their metabolism and bioavailability.

Pre-treatment with clopidogrel in the patient subgroup of the CLARITY-TIMI 28 study3 undergoing PCI reduced the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) without a significant increase in bleeding.4 However, PCI was performed hours after thrombolysis. Successively, two studies on primary PCI did not reveal any significant benefit from pre-treatment.5,6 Lastly, the ACTION meta-analysis showed a significant reduction in MACE with clopidogrel pre-treatment without increase in major bleeds.7

The superiority of prasugrel and ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel in reducing MACE in ACS patients was demonstrated by both TRITON TIMI-388 and PLATO studies.9 The new antiplatelet drugs were more effective than clopidogrel even in the STE ACS subgroup10,11; however, very few data are available on pre-treatment and in patients undergoing primary PCI.

The only randomized trial on pre-hospital treatment with a P2Y12 inhibitor is the ATLANTIC study,12 in which no difference was observed in pre- and post-PCI reperfusion markers by ticagrelor pre-treatment, compared with its cath lab administration; the mean time difference between the two strategies was a mere 31 min. Pre-treatment with ticagrelor did not reduce MACE, but without an increased risk of bleeding.

Despite the lack of evidence from randomized trials, early administration of a P2Y12 inhibitor, preferably prasugrel or ticagrelor, would seem advisable, even in the ambulance if allowed by local organization, especially if the patient transport time exceeds 30 min. The administration of clopidogrel must be reserved for cases in which prasugrel and ticagrelor are contraindicated or not available.2

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPI) have been used in STE ACS to obtain an effective anti-platelet action during angioplasty. A meta-regression performed by De Luca G. et al.13 showed a significant relationship between the patient risk profile and the reduction in mortality in patients pre-treated with GPI. However, many of the studies included were conducted without systematic use of GPI.

In patients pre-treated with clopidogrel, the HORIZONS-AMI trial14 showed the superiority of pre-treatment with bivalirudin over unfractionated heparin combined with abciximab. In patients pre-treated with a loading dose of clopidogrel, the BRAVE-3 study15 did not show any advantage from the administration of abciximab on the amount of myocardial necrosis.

These data suggest that routine up-stream use of a GPI does not yield benefits in terms of outcome, whilst increasing the risk of bleeding,16 and is therefore generally not indicated. It may be considered in patients with a high thrombotic risk and low haemorrhagic risk, for whom PCI is delayed due to longer transfer time.12,17

Anticoagulants

Although there are no specific data on the up-stream administration of unfractioned heparin (UFH) in patients with STE ACS scheduled for primary PCI, its use would appear to be reasonable.2

Enoxaparin is a potential option; however, in the ATOLL study18 it doesn’t demonstrate to be superior to UFH in reducing ischaemic and haemorrhagic events.

Bivalirudin would appear to be preferable in patients at high haemorrhagic risk, for its efficacy similar to UFH associated with GPI but with a lower incidence of bleeding; its use was associated with a reduction in total and cardiovascular mortality, but increased the incidence of intra-stent thrombosis.19,20 It should be pointed out that bivalirudin favourable results have not always been confirmed.21,22

It is not therefore possible to pinpoint the best anticoagulant treatment, but the choice should be taken depending on the characteristics of the individual patient. In cases of low haemorrhagic risk and low thrombotic burden, UFH or enoxaparin are reasonable options. In those patients treated with a combination of UFH and GPI, which guarantees excellent antithrombotic efficacy but increases haemorrhagic risk, it is fundamental not to overdose heparin and to privilege radial access. Bivalirudin, on the other hand, should be preferred in patients with a higher haemorrhagic risk or in those with delayed presentation, in whom GPI are less effective.

Anticoagulant therapy should be discontinued after PCI, except in patients in whom it has a specific indication or for the prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism.

There are no randomized studies available on parenteral anticoagulant therapy in patients on oral anticoagulant therapy (OAT) to be treated with primary PCI, only expert opinions.23,24 Regardless of whether the patient is on treatment with a vitamin K antagonist or with a new oral anticoagulant (NOA), it is nevertheless required to administer an additional dose of i.v. anticoagulant, like reduced-dose UFH or bivalirudin, which has a lower bleeding risk.

Anti-ischaemic drugs

Beta-blockers

Beta-blockers have shown to reduce mortality in the acute phase of STE ACS in the pre-thrombolytic age25,26; however, the evidence of a benefit in primary PCI treated patients is inconsistent. Early use of high doses is associated with increased mortality,27 particularly in patients at risk of developing cardiogenic shock.28

Calcium channel-blockers

Verapamil and diltiazem own an efficacy similar to that of beta-blockers in reducing heart rate and symptoms; however, in the acute phases of STE ACS they could be potentially harmful and should therefore not be used.29

Nitrates

Routine administration of nitrates in STE ACS is generally not recommended2; their usefulness has been however, acknowledged in patients with hypertension or heart failure.

Statins

In patients with STE ACS high-dose statins should be administered early and continued in the long term, with a target low density lipoprotein cholesterol level (C-LDL) below 70 mg/dL.2 This treatment is recommended regardless of reperfusion therapy.

Statins could have ‘pleiotropic effects’ on vessel walls, with anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antithrombotic properties that could improve endothelial function and stabilize the atherosclerotic disease.30 They have been used in primary PCI in an attempt to reduce the extent of myocardial damage and favour optimal reperfusion.31–35 High doses of high efficacy statins (atorvastatin 80 mg and rosuvastatin 40 mg), administered immediately before primary PCI could improve both epicardial (TIMI flow and TIMI frame count) and myocardial reperfusion (TIMI myocardial perfusion grade or myocardial blush grade), and could reduce the incidence of no-reflow and the levels of myocardial damage markers.

Studies on this topic are too small to demonstrate a definite effect of pre-treatment; however, given the lack of significant side effects in the acute phase, it would seem appropriate to suggest their early administration.

In Italy statin prescription is ruled by circular no. 13 issued by the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA),36 which identifies high-dose atorvastatin (≥40 mg/day) as the first treatment option in patients with ACS and/or undergoing myocardial revascularization.

Suggested treatment options for STE ACS patients are summarized in Table 1.

|

|

UFH, unfractioned heparin; ASA, acute coronary syndromes; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

aAs an alternative to UFH.

bAfter or as an alternative to UFH.

cIn addition to ASA.

dIn patients at low bleeding risk and at high ischaemic risk to be transferred to a PCI centre.

eAs an alternative to i.v. ASA.

fAs an alternative to oral ASA.

|

|

UFH, unfractioned heparin; ASA, acute coronary syndromes; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

aAs an alternative to UFH.

bAfter or as an alternative to UFH.

cIn addition to ASA.

dIn patients at low bleeding risk and at high ischaemic risk to be transferred to a PCI centre.

eAs an alternative to i.v. ASA.

fAs an alternative to oral ASA.

Non ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome

Antiplatelet drugs

Oral antiplatelet agents

The ESC 2011 guidelines on NSTE ACS37 recommended the administration of aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitors ‘as soon as possible’, whereas the 2015 edition suggests that this treatment should be administered timely from the time of diagnosis, without however providing specific indications about when, and recommending haemorrhagic risk stratification.1 Invasive strategy should be adopted:

immediately (within 2 h of diagnosis) for patients with haemodynamic or electric instability, or another very high risk criterion;

early (with 24 h of diagnosis) in patients with at least one high risk criterion, including troponin elevation;

electively (within 72 h of diagnosis) in patients with at least one intermediate ischaemic risk criterion.

Aspirin

Aspirin has demonstrated to be effective in patients with unstable angina38; the incidence of myocardial infarction or death was reduced in four trials in the pre-PCI era.39–42 A meta-analysis of these studies showed a significant reduction at 2 years in the MACE rate.43 However, there are no specific data available on the administration before an invasive strategy.

Clopidogrel

The pre-treatment strategy comes from the results of the PCI-CURE trial,44 in which a 30% reduction in the primary endpoint of death, infarction or stroke was seen in patients pre-treated with clopidogrel; however, this sub-group represents only about 20% of the whole CURE trial population, and the average time interval between pre-treatment and PCI was 10 days, which is far longer than nowadays.

Prasugrel

The only randomized trial on pre-treatment with a P2Y12 inhibitor in patients with NSTE ACS is the ACCOAST study,45 in which patients intended for an invasive approach were randomized to receive pre-treatment with an oral loading dose of 30 mg of prasugrel followed by a further oral 30 mg load at the time of PCI, or the administration of 60 mg of prasugrel in the cath lab. The mean duration of pre-treatment was 4.3 h. At 7 days no reduction was observed in the occurrence of the primary endpoint, while major bleeds where significantly increased in the pre-treatment arm. Pre-treatment with prasugrel in patients with NSTE ACS is therefore not recommended.1

Ticagrelor

In the NSTE ACS patient subgroup of the PLATO study, the primary composite efficacy endpoint was significantly reduced by ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel;46 however, results in patients actually pre-treated are not available.

Intravenous antiplatelet agents

Cangrelor

Cangrelor is a direct reversible inhibitor of P2Y12 receptor, that has been compared with clopidogrel in patients undergoing PCI,47–49 most of whom affected by ACS. A meta-analysis of these trials showed that the infusion of cangrelor reduced the relative risk of the composite endpoint (peri-procedural death, myocardial infarction, ischaemia-guided revascularization and intra-stent thrombosis), determining also an increase in minor and major bleeds, but not in the need for transfusions.50

European Society of Cardiology guidelines suggest considering pre-treatment with cangrelor in patients who are not treated with a P2Y12 inhibitor.1 Cangrelor, which has been approved by the European Medicines Agency, is currently not available in Italy.

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors

Up-stream use of GPI in patients with NSTE ACS has been studied in two trials. In the ACUITY,51 the deferred GPI administration strategy compared with the up-stream use led to a significant reduction at 30 days in major bleedings not related to CABG, without any difference in the primary efficacy endpoint. The EARLY-ACS study52 did not reveal any significant reduction in the primary endpoint occurrence in the arm pre-treated with eptifibatide compared with the optional use arm, but showed a significant increase in major bleeds. Lastly, a meta-analysis indicated that GPI pre-treatment did not reduce mortality or myocardial infarction recurrence at 30 days, with a significant increase in major bleeds.53 Thus pre-treatment with GPI inhibitors is not recommended.1

Proposed ‘decision-making’ scheme for pre-treatment with a P2Y12 inhibitor

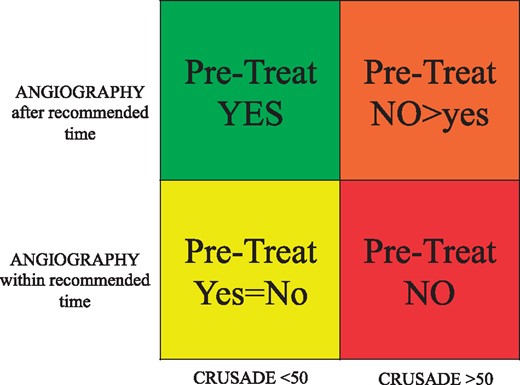

We propose a decision-making scheme for pre-treatment in NSTE ACS patients based on the ESC stratification of the ischaemic risk,1 on the timing of the coronary angiography and on the haemorrhagic risk, assessed by the CRUSADE score,54 choosing a cut-off value of 50 that identifies patients at high risk of major bleeds.

Time to invasive strategy is longer than recommended in a significant amount of patients in Italy,55 in Europe56,57 and in the USA.58 Sometime this deferral could be related to associated clinical conditions that recommend stabilization or a more thorough diagnosis before performing coronary angiography; in the majority of cases, however, the delay stems from the need to transfer the patient in hospitals with cath labs.

Patients at very high ischaemic risk

In case of invasive intervention within 2 h, the oral load of P2Y12 inhibitor will be ineffective at the time of the procedure, and it would therefore appear to be preferable to use GPI if needed, given also their faster resolution of the effect in case of need of a surgical treatment. However, pre-treatment with ticagrelor or prasugrel is not excluded, mainly when the ischaemic risk is far greater than the haemorrhagic risk and the likelihood of surgery is not high.

Patients at high or moderate ischaemic risk

In case of very high haemorrhagic risk, identified by a CRUSADE score ≥ 50, pre-treatment is usually not recommended (red box), and only if the time to the coronary angiography is longer can pre-treatment be considered in selected cases (orange box) (Figure 1).

Pre-treatment with P2Y12 inhibitors in non ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes at moderate/high risk.

In case of a CRUSADE score <50 pre-treatment is not mandatory but however allowed (yellow box) if coronary angiography will be performed within the recommended time; if the angiography is delayed, pre-treatment with P2Y12 inhibitors would appear to be appropriate (green box).

Patients at low ischaemic risk

In patients with NSTE ACS at low ischaemic risk pre-treatment with P2Y12 inhibitors is not recommended.1

Anticoagulants

The anticoagulant of choice in NSTE ACS should be fondaparinux, due to its more favourable efficacy and safety profile compared with UFH and enoxaparin.1,59,60 In patients pre-treated with fondaparinux an additional bolus of standard-dose UFH must be administered at the time of PCI.

Enoxaparin and UFH are recommended when fondaparinux is not available.13 There are no conclusive data regarding the superiority of one drug over the other.61 In a meta-analysis of over 30 000 patients, enoxaparin compared with UFH determined a slight decrease in the composite endpoint of death and myocardial infarction at 30 days without differences in terms of major bleeds.62 In patients pre-treated with enoxaparin is strongly recommended to avoid to switch to UFH, unfortunately frequently done,55 due to a higher risk of ischaemic and haemorrhagic complications.63 UFH is particularly indicated in patients with severe renal insufficiency.

In the ACUITY study64 bivalirudin was non-inferior to UFH in the reduction of ischaemic events, reducing also major bleeds, but it has to be administered only at the time of the PCI. The usefulness of continuing its infusion after PCI in order to reduce the risk of intra-stent thrombosis was recently questioned.22

Anticoagulation should be discontinued after PCI, except in those patients in whom it has a specific indication.

In patients with NSTE ACS candidates to coronary angiography while on chronic OAT with vitamin K inhibitors or NOA there are still no consistent data. OAT can be stopped and replaced by UFH or enoxaparin, or could be continued at reduced dosages, in order to reduce the risk of both thromboembolic and haemorrhagic events. It is not necessary to administer UFH during PCI if the INR value is greater than 2.5, whereas in case of NOA treatment, administration of an additional intravenous bolus of UFH is recommended.1,23,24

Anti-ischaemic drugs

Beta-blockers

The administration of beta-blockers in NSTE ACS patients demonstrated to reduce in-hospital mortality, except that in patients at risk of cardiogenic shock or with unknown left ventricular function.65

Calcium channel-blockers

Diltiazem and verapamil are possible alternatives in case of contraindications to the use of beta-blockers. They can be used to control angina or in case of vasospasm.1

Nitrates

Nitrates are highly effective in reducing angina and are particularly suitable in patients with incomplete blood pressure control. Their usefulness remains limited to symptom control.1

Statins

The evidences in favour of pre-treatment with high doses of statins in case of PCI in patients with NSTE ACS were summarized in a meta-analysis66 that shows how the administration of atorvastatin 80 mg or rosuvastatin 40 mg before PCI is associated with a reduction in the incidence and amount of post-procedural necrosis, as expressed by lower myocardial damage markers levels, and of short-term MACE.

Reloading is also advisable in patients who are already treated with statins.67

Suggested treatment options for NSTE ACS patients are summarized in Tables 2and3.

Non ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes pre-treatment: very high risk

|

|

UFH, unfractioned heparin; ASA, acute coronary syndromes.

Non ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes pre-treatment: very high risk

|

|

UFH, unfractioned heparin; ASA, acute coronary syndromes.

Non ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes pre-treatment: moderate/high risk

|

|

UFH, unfractioned heparin; ASA, acute coronary syndromes.

aIn addition to ASA.

bSee risk/time schedule.

cPt. with severe kidney disease.

dIn patient with heparin induced thrombocytopenia.

Non ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes pre-treatment: moderate/high risk

|

|

UFH, unfractioned heparin; ASA, acute coronary syndromes.

aIn addition to ASA.

bSee risk/time schedule.

cPt. with severe kidney disease.

dIn patient with heparin induced thrombocytopenia.

Patients with stable ischaemic heart disease

Antiplatelet drugs

Aspirin pre-treatment is recommended in all PCI candidates, also if there are no specific data available.68

In the lack of studies, ESC guidelines suggest a loading dose of clopidogrel before PCI when coronary anatomy is known, recommending its administration at least 2 h before the procedure;68 guidelines take also into consideration a loading dose of clopidogrel in patients with a high likelihood of coronary stenosis to revascularize.38,68,69 In patients who are already on treatment with clopidogrel, reloading with 600 mg can be considered once angioplasty is planned.

There are no data available on the use of ticagrelor and prasugrel in non-ACS patients, so their administration is not recommended.

Use of GPI should be reserved as rescue therapy in case of intra-procedural thrombotic complications.70

Anticoagulants

In patients with stable ischaemic heart disease the aim of anticoagulant therapy is to reduce the risk of peri-procedural thrombotic complications, and it should therefore only be administered at the time of PCI.

UFH remains the standard of care.71 Enoxaparin can be used as alternative to UFH.72 Bivalirudin should be reserved for patients at very high bleeding risk.73

In stable patients on OAT it is reasonable to continue administration of vitamin K inhibitors, adding a reduced dose of UFH only in case of radial approach. The great handling of NOAs makes it easy to temporarily stop treatment.23,24,74

Anti-ischaemic drugs

In general, there is no specific need of anti-ischaemic treatment before a revascularization procedure, if not those suited to the patient's specific clinical condition.

Statins

Statins are recommended with the aim of keeping C-LDL levels below 70 mg/dL.68 Pre-procedural administration in stable patients is thought to be effective to prevent contrast-induced kidney disease.75

A recent meta-analysis76 showed that pre-treatment with high doses of high-efficacy statin is associated with a reduction in the risk of peri-procedural myocardial necrosis, and a reduction in short-term MACE.

It would therefore appear advisable to administer an oral loading dose of 80 mg of atorvastatin or 20–40 mg of rosuvastatin before elective percutaneous revascularization procedure. Reloading is appropriate in patients already on therapy with another statin.77

Suggested treatment options for stable ischaemic heart disease patients are summarized in Table 4.

|

|

UFH, unfractioned heparin; ASA, acute coronary syndromes; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

aIn addition to ASA in case of scheduled PCI for known anatomy or high likelihood of PCI.

|

|

UFH, unfractioned heparin; ASA, acute coronary syndromes; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

aIn addition to ASA in case of scheduled PCI for known anatomy or high likelihood of PCI.

Patients candidates to coronary artery bypass grafting

Most patients who are candidates to CABG are on treatment with antiplatelet, anticoagulant, beta-blocker and statin therapy, whose pre-operative administration must be managed in order to maintain their cardio-protective effects, but avoiding to increase bleeding or hypotension.

Antiplatelet drugs

Antiplatelet drugs improve short- and long-term outcomes even in patients undergoing CABG;78,79 bleeding is however a serious and common complication80,81 that implies an additional risk of further adverse events.82–84

Pre-operative discontinuation of aspirin is considered to be risky in patients with ACS or with coronary stents,85 and it should only be considered in case of a very high risk of bleeding or in patients who refuse transfusions, stopping treatment three days before the procedure.86,87

In patients with stable coronary disease, the benefits of continuing therapy with aspirin up to the day of the procedure are less well defined. It was highlighted a slight increase in the risk of bleeding without improving the early graft patency rate.88 The ATACAS trial89 did not reveal any differences in major bleeds with the pre-operative use of aspirin, nor a reduction in thrombotic events or in mortality, possibly due to the low risk of the population studied.

Prasugrel compared with clopidogrel significantly increases post-operative bleedings, including fatal ones; however, after discontinuation of the drug, post-operative mortality was lower than for patients treated with clopidogrel.90

Ticagrelor demonstrated peri-operative bleeding risk similar to clopidogrel,91 but mortality in patients treated 3–5 days after the last administered dose was significantly lower.92 Ticagrelor has a reversible binding with platelets, and may remain in circulation for a long time, inhibiting also transfused platelets.93 A specific antidote is currently being developed.94

It may be appropriate to monitor platelet inhibition with dedicated tests, in order to limit the antiplatelet discontinuation period to 1–2 days.95,96

These are the ESC guidelines suggestions:37,68in case of high or very high risk of haemorrhage:

aspirin should be maintained for the entire surgical period;

clopidogrel and ticagrelor should be discontinued 5 days before the procedure;

prasugrel should be discontinued 7 days before;

in case of high or very high thrombotic risk (clinical and/or anatomical):

aspirin should be maintained for the entire surgical period;

in emergency, discontinuing the P2Y12 inhibitor is not recommended and all possible measures must be taken to reduce the risk of bleeding;

in case of urgent surgery, consider to perform the procedure after 1-2 days of discontinuation.

In case of very high both thrombotic and ischaemic risk, ‘bridging’ strategies with short half-life intravenous anti-platelet drugs were evaluated:

discontinuation of clopidogrel 5 days before the procedure and administration of tirofiban or eptifibatide i.v. up to 4 h before;97

discontinuation of thienopyridine (99% clopidogrel) 48 h before the procedure and administration of intravenous cangrelor up to 1–6 h before.98

Replacing double antiplatelet therapy with heparin is not recommended.

A P2Y12 inhibitor should be administered as soon as possible after the procedure, as it improves graft patency and outcome at 30 days.99,100

Anticoagulants

In patients treated with vitamin K inhibitors, normal INR values must be restored before an elective procedure. The use of low molecular weight heparin as a therapeutic bridge may increase the risk of peri-procedural bleeding.100 In case of emergency/urgency, vitamin K and/or transfusions of fresh plasma or prothrombin complex concentrates may be administered.101

If a NOA is used, it should be discontinued 48–96 h before a scheduled procedure, taking into account the patient's kidney function and the drug used,102 without bridging with heparin.74,100,103

Laboratory tests to measure NOA effects have not yet been validated, as the relationship between the value of the measured parameter and the risk of bleeding is not known.102

In case of urgent heart surgery, it would seem preferable to wait until the NOAs are no longer effective. In case of emergency procedures, activated prothrombin complexes may be used.104

Specific inhibitors have so far been studied on a very limited number of patients. Idarucizumab is an antibody fragment that in a few minutes overrides the effect of dabigatran,105 whereas Andexanet inhibits the effect of anti-Xa NOA.106

The administration of NOAs should not be restarted earlier than 48–72 h after the procedure, and there are no data available on use at reduced dosages.

Beta-blockers

The enthusiasm on the use of these drugs was curbed by the results of a meta-analysis,107 by the results of a Texas Heart Surgery Society database,108 and by a retrospective analysis of the data of over 500 000 patients without recent myocardial infarction109: pre-operative use did not lead to a mortality reduction, while slightly increased the incidence of atrial fibrillation; the underlying mechanism is possibly related to hypotension.

Statins

Statins reduce the development of venous graft disease110; pleiotropic effects are associated with a reduction in adverse clinical events and to cardiovascular protection.111,112

Despite these premises, a review113 on pre-operative treatment indicated as the only result a reduction in the incidence of post-operative atrial fibrillation and consequently of the duration of hospitalization. There were no significant effects on mortality, stroke, peri-operative infarction or kidney disease.

Conclusions

The antithrombotic drugs administration before coronary angiography in patients with coronary disease on the one hand may make it possible to bring forward optimal therapy but on the other it may expose to risk of bleeding that, particularly in patients with ACS, can weigh heavily on prognosis, even more so than the theoretical benefit of pre-treatment.

In NSTE ACS patients in particular, we suggest a ‘selective pre-treatment’ with P2Y12 inhibitors, guided by a careful assessment of both ischaemic and haemorrhagic risk, whilst also taking into consideration the actual time delay before the coronary angiography.

Many of the issues regarding this topic could be solved by early access to coronary angiography, particularly in patients at greatest risk of events.

Consensus Document Approval Faculty

Abrignani Maurizio Giuseppe, Alunni Gianfranco, Amodeo Vincenzo, Angeli Fabio, Aspromonte Nadia, Audo Andrea, Azzarito Michele, Battistoni Ilaria, Bianca Innocenzo, Bisceglia Irma, Bongarzoni Amedeo, Bonvicini Marco, Cacciavillani Luisa, Calculli Giancarlo Giacinto, Caldarola Pasquale, Capecchi Alessandro, Caretta Giorgio, Carmina Maria Gabriella, Casazza Franco, Casu Gavino, Cemin Roberto, Chiarandà Giacomo, Chiarella Francesco, Chiatto Mario, Cibinel Gian Alfonso, Ciccone Marco Matteo, Cicini Maria Paola, Clerico Aldo, D'Agostino Carlo, De Luca Giovanni, De Maria Renata, Del Sindaco Donatella, Di Fusco Stefania Angela, Di Lenarda Andrea, Di Tano Giuseppe, Egidy Assenza Gabriele, Egman Sabrina, Enea Iolanda, Fattirolli Francesco, Favilli Silvia, Ferraiuolo Giuseppe, Francese Giuseppina Maura, Gabrielli Domenico, Giardina Achille, Greco Cesare, Gregorio Giovanni, Iacoviello Massimo, Khoury Georgette, Lucà Fabiana, Lukic Vjerica, Macera Francesca, Marini Marco, Masson Serge, Maurea Nicola, Mazzanti Marco, Mennuni Mauro, Menotti Alberto, Mininni Nicola, Moreo Antonella, Mortara Andrea, Mureddu Gian Francesco, Murrone Adriano, Nardi Federico, Navazio Alessandro, Nicolosi Gian Luigi, Oliva Fabrizio, Parato Vito Maurizio, Parrini Iris, Patanè Leonardo, Pini Daniela, Pino Paolo Giuseppe, Pirelli Salvatore, Procaccini Vincenza, Pugliese Francesco Rocco, Pulignano Giovanni, Radini Donatella, Rao Carmelo Massimiliano, Riccio Carmine, Roncon Loris, Rossini Roberta, Ruggieri Maria Pia, Rugolotto Matteo, Sanna Fabiola, Sauro Rosario, Severi Silva, Sicuro Marco, Silvestri Paolo, Sisto Francesco, Tarantini Luigi, Uguccioni Massimo, Urbinati Stefano, Valente Serafina, Vatrano Marco, Vianello Gabriele, Vinci Eugenio, Zuin Guerrino.

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Roberto Caporale reports honoraria for consulting from Lilly and Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Alberto Menozzi reports honoraria for lectures and consulting from Astra-Zeneca, Abbott Vascular, Bayer, Correvio, Daiichi-Sankyo, Medtronic, MSD, The Medicines Company. Giuseppe Musumeci reports honoraria for lectures from Daiichi Sankyo, Astra Zeneca, Menarini, Servier and Abbott Vascular. Prof. Giuseppe Tarantini reports honoraria for lectures from Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical, Philips Volcano, Medtronic and Abbott Vascular.

References

- acute coronary syndromes

- anticoagulants

- antiplatelet agents

- fibrinolytic agents

- beta-blockers

- ischemia

- coronary angiography

- statins

- cardiologists

- coronary revascularization

- st segment elevation

- cardiac surgery procedures

- cardiology

- pharmacology

- consensus

- Interventional Cardiology

- risk of excessive or recurrent bleeding