-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Stanisław Surma, Dimitri P Mikhailidis, Maciej Banach, Celebrating the 90th birthday of the scientist who discovered statins: Akira Endō, European Heart Journal, Volume 45, Issue 9, 1 March 2024, Pages 647–650, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad831

Close - Share Icon Share

Dr Akira Endō—the father of statins

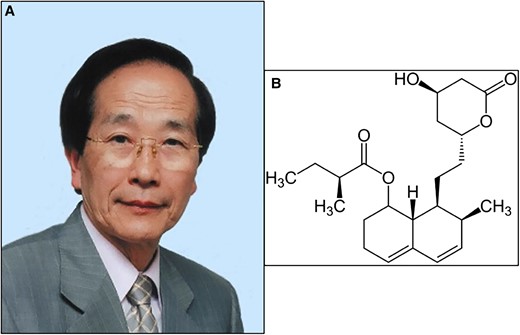

In 1971, Dr Akira Endō (Figure 1A), working at the Sankyo company in Tokyo, speculated that fungi not only contained antibiotics but also inhibitors of other processes, such as cholesterol metabolism. Over a period of several years, he screened >6000 fungal cultures until a positive result emerged.1 This compound, which was named compactin (mevastatin), came from the blue-green mould Penicillium citrinum Pen-5 that was isolated from a rice sample collected at a grain shop in Kyoto. Based on biochemical assays, compactin (mevastatin) (Figure 1B) is the first known statin.1 On 14 November 2023, Dr Akira Endō celebrated his 90th birthday. His discovery not only made statins the gold standard for lipid-lowering treatment (LLT), but also changed the natural history of cardiovascular (CV) disease (CVD) treatment and prolonged the lives of patients, both in primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention.2 For the past decades, statins are the most commonly used ‘cardiology’ drugs in the world.2 After over 50 years of natural ‘statin history’, we have prepared a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis to summarize where we are and why we still underuse these drugs.

A—Dr Akira Endō (source: https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akira_End%C5%8D; no permisision required); B—compactin (mevastatin)—the first known statin discovered by Dr Akira Endō (public domain, no permission required).

[S]trengths—statins improve cardiovascular prognosis and prolong life

Statins are the gold standard of lipid-lowering therapy and their use is associated with improved CV outcomes (Figure 2). A meta-analysis of 94 000 patients in primary CV prevention showed that the use of statins reduced the risk of: non-fatal acute coronary syndrome (ACS) by 38%, CV mortality by 20%, all-cause mortality (ACM) by 11%, non-fatal stroke by 17%, unstable angina by 25%, and composite major CV events (MACE) by 26%.3 Similarly positive results were obtained in a meta-analysis of 11 RCTs with 58 504 participants in primary prevention. Acute coronary syndrome risk was reduced by 44%, major cerebrovascular events by 22%, major coronary events by 33%, composite CVD outcome by 29%, revascularizations by 35%, angina by 24%, and CVD hospitalization by 26%.4 The use of statins in patients for secondary CVD prevention is associated with even more convincing results with ACM risk reduced by 22%, CVD mortality by 31%, ACS by 38%, a need for coronary revascularization by 44%, and cerebrovascular events by 25%.5 Each reduction in serum low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) by 1 mmol/L (40 mg/dL) was associated with a reduction in MACE risk by 12% (95% CI: 8%–16%) in the 1st year, 20% (16%–24%) in the 3rd year, 23% (18%–27%) in the 5th year, and 29% (14%–42%) in the 7th year of LLT.6

SWOT analysis of lipid-lowering treatment with statins. LLT, lipid-lowering therapy; CV, cardiovascular; ACS, coronary acute syndrome; CAD, coronary artery disease; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; SI, statin intolerance; SAMS, statin-associated muscle symptoms; AEs, adverse events; NOD, new-onset diabetes; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; PAD, peripheral artery disease; HeFH, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia; FDC, fixed dose combination; HIS, high intensity statin; EZE, ezetimibe; BA, bempedoic acid; OBICE, obicetrapib; PCSK9m, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 modulator

Elevated LDL-C levels in younger people increase the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) to a greater extent compared with the same exposure in older people. This emphasizes the need to control LDL-C at the earliest possible stage (=lifetime).2 More intensive statin treatment allows for an additional 24% reduction in ASCVD risk and by 10% ACM risk.2–6 Therefore, LLT with statins to be maximally effective should be carried out in accordance with the following principles: ‘the lower the better’, ‘the longer the better’, and ‘the earlier the better’.2

[W]eaknesses—statin intolerance—but is it really a significant problem and weakness?

Statin intolerance (SI) should be reconsidered since they are one of the best tolerated drugs in cardiology.2 However, due to lack of physician and patient comprehensive knowledge, anti-statin movements from the very beginning, media that prefer to unfavourably present statins, and fake news, SI has been inappropriately considered as a weakness. In this context, a study by Jones et al. found that the prevalence of misinformation on statins on websites was 22.5%; this had a significant impact since almost 60% of participants recommended that their relatives ignore statin prescriptions. This study also showed that providing information about the benefits and ways to deal with potential (rare) side effects of statins significantly increased adherence.7

A drug that does not cause side effects has no effect at all. The reason for not using statins is mostly the fear of intolerance, something we call a drucebo effect that might be responsible for up to 90% of SI cases.8 The world’s largest meta-analysis of 176 clinical studies, including 4 143 517 patients showed that the overall prevalence of SI worldwide is 9.1% (8.1%–10%), and when diagnosed with the approved definitions, it was only 5.9%–7%.9 In other words, SI is in most of the cases overdiagnosed, and 93% of patients on a statin can be treated effectively without any safety concerns.9 After ruling out the drucebo effect and excluding the risk factors and conditions that might increase SI risk, any statin treatment can be continued in up to 98% of cases.2,9 The most frequently reported side effects of statins (those with confirmed causality) include statin-associated muscle symptoms (serious SAMS: <0.1%), temporary elevation of liver enzymes (in most of the cases, they return to normal levels after 4–8 weeks of therapy), and new-onset diabetes (however, the risk is 5× less than CVD benefits associated with statin therapy).8 In patients with a higher risk of SAMS (e.g. polypharmacy) and a high risk of diabetes or with already existing diabetes, pitavastatin might prove to be another option to optimize the treatment of lipid disorders10 (Figure 2).

[O]pportunities—lipid-lowering treatment based on statins allows to reduce LDL-C levels by >85%

Recently, due to the ineffectiveness of LLT with only one-third to one-fourth of patients reaching their LDL-C target, we have made a switch from the high intensity statin therapy to intensive lipid-lowering combination therapy.2 Depending on the therapeutic goal (determined individually for each patient based on CV risk and baseline LDL-C level), a treatment with appropriate lipid-lowering potency is selected.2 The use of combinations of lipid-lowering drugs allows to reduce LDL-C level by >85% [strong statin in highest dose + ezetimibe + bempedoic acid + proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) targeted therapy approach].2 In patients at high to extremely high CVD risk, the upfront lipid-lowering combination therapy not only allows to achieve LDL-C targets more frequently, significantly reduces the number of side effects and the risk of discontinuation, but also reduces the risk of CV outcomes [by 25% in 3-year follow-up; absolute risk reduction (ARR) 3.6%] and ACM (by 47%, ARR 4.7%).11 Therefore, LDL-C goal achievement is possible for most patients (Figure 2).11

[T]hreats—lack of adherence to statin therapy is an independent cardiovascular disease risk factor

A lack of adherence to statin/lipid-lowering therapy and failure to achieve therapeutic goals are common problems in clinical practice.8,11 The SANTORINI (Treatment of High and Very High riSk Dyslipidemic pAtients for the PreveNTion of CardiOvasculaR Events) study showed that in patients with high or very high CV risk, only 20.1% achieved their target serum LDL-C level according to the 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines (24% of high-risk patients and 18.6% of very high-risk patients, respectively).12 Moreover, as many as 21.8% of patients did not receive any LLT (23.5% and 21.1%, respectively), statin monotherapy was used by 54.3% of patients (58.4% and 52.5%, respectively), combined therapy was used in 24% of patients (18.1% and 26.4%, respectively), and most often, this was a combination of a statin and ezetimibe.12

Based on the available evidence, non-adherence to statin therapy, which may result from statin-associated side effects, but also patient non-compliance (because of lack of patient education and ineffective communication), and physician inertia, is an independent CVD risk factor.8,11 A study involving 347 104 ASCVD patients on statins showed that compared with the most adherent patients, the risk of death increased by 8%–30% as adherence deteriorated.13 Another study involving nearly 55 000 patients with ACS showed that 20% of the participants were non-adherent to statin treatment during the first year. This translated into a significantly higher risk of all-cause mortality (by 71%) and CV mortality (by 62%).14 A systematic review indicated that lack of adherence to statin treatment increased the risk of ASCVD by up to 5 times, ACM by 2.5 times, while lack of persistent treatment increases the risk of CVD and mortality by 1.7 times and 5 times, respectively2,8,11 (Figure 2).

Conclusions

Statins, which were developed after the discovery by Dr Akira Endō, revolutionized medicine and proved to be the most effective treatment for reducing the risk associated with ASCVD and prolonging life. Despite this evidence, these drugs are underused. This situation can only be changed by improving the knowledge of patients and prescribers regarding the importance of using statins in patients with CVD. Knowledge regarding how to deal with SI is also critically important.

Declarations

Disclosure of Interest

S.S.: honoraria from: Novartis/Sandoz and Pro.Med.; D.P.M. has nothing to disclose; M.B.: speakers bureau: Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, KRKA, Polpharma, Mylan/Viatris, Novartis, Novo-Nordisk, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Teva, and Zentiva; consultant to Adamed, Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, Esperion, NewAmsterdam, Novartis, Novo-Nordisk, and Sanofi-Aventis; grants from Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, Mylan/Viatris, Sanofi, and Valeant.