-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Gianfranco Parati, Alessandro Croce, Grzegorz Bilo, Blood pressure variability: no longer a mASCOT for research nerds, European Heart Journal, Volume 45, Issue 13, 1 April 2024, Pages 1170–1172, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae023

Close - Share Icon Share

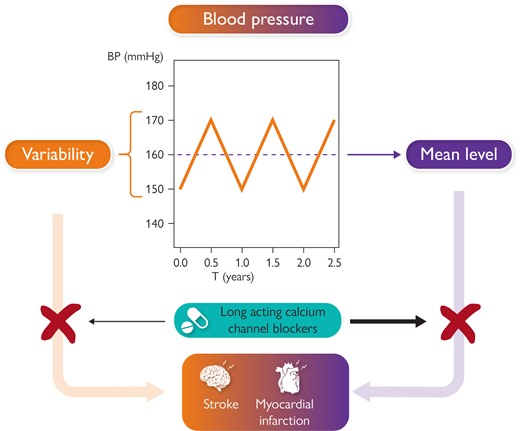

Figure illustrates the contribution of both blood pressure mean level and blood pressure variability to increased risk of cardiovascular events, such as stroke and myocardial infarction. The figure also illustrates the possibility suggested by available studies to antagonize the impact on cardiovascular risk of either increased mean blood pressure level and enhanced blood pressure variability through administration of long acting calcium channel blockers.

This editorial refers to ‘Legacy benefits of blood pressure treatment on cardiovascular events are primarily mediated by improved blood pressure variability: the ASCOT trial’, by A. Gupta et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad814.

In the field of cardiovascular health, blood pressure (BP) has long been recognized as a pivotal determinant of outcome. Nonetheless, even optimal control of average BP levels and other established risk factors does not fully protect from cardiovascular complications. Understanding the factors responsible for such a failure and reducing this residual risk remain important challenges.

BP is a highly variable parameter, and this may contribute to the difficulties still faced in our time to reduce cardiovascular damage induced by hypertension. BP variability (V) is a complex phenomenon encompassing changes in BP occurring over various time spans. In spite of the convincing evidence demonstrating its prognostic importance,1–3 the role of BPV as an independent risk factor, able to reclassify cardiovascular risk, is still not universally acknowledged outside the narrow circle of enthusiastic researchers.1

One of the first major studies showing the relationship between visit-to-visit BPV (VVV, an estimate of BP variations between clinic visits) and outcome was a post-hoc analysis of the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA) trial, with data published in 2010. In this analysis, VVV of systolic (S)BP not only independently predicted outcome but appeared superior to mean BP levels in this regard.4 Moreover, the ASCOT data provided evidence that VVV may be better reduced by long-acting calcium channel blocker (CCB; amlodipine)-based antihypertensive treatment, compared with a beta-blocker (atenolol)-based regimen.5 Further analyses of trial data supported the potential role of CCBs in BPV reduction and, indirectly, suggested that this effect may contribute to improved outcome.6 Notwithstanding this evidence, BPV is still seen mainly as a research issue and not addressed by the current hypertension management guidelines on either side of the Atlantic.

In the current issue of the European Heart Journal, Gupta et al. report the results of long-term follow-up of the ASCOT-BPLA trial, looking specifically at two main aspects: (i) whether VVV during the trial had an impact on the outcomes registered over extended follow-up; and (ii) whether the difference in VVV between treatment arms observed in the randomized phase may mediate the potential differences in long-term outcomes. To that end, the authors analysed the outcomes based on linked hospital and mortality records over a median period of 17.4 years (up to 21 years).7 The main findings may be summarized as follows: (i) systolic VVV was a strong predictor of cardiovascular events [hazard ratio (HR) per 5 mmHg (roughly corresponding to 1 SD) increase in SBP VVV was 1.22, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.18–1.26], independently of and possibly superior to average BP levels, with similar HRs observed for all investigated outcomes; this was also true in participants with well controlled BP; (ii) the risk of several key outcomes (including stroke and coronary events) remained significantly lower in the amlodipine-based treatment arm over the extended follow-up. Data obtained in a subgroup in which more detailed information was available after 10 years follow-up suggest that this was true despite considerable changes in treatment strategy, with many participants who switched to other drug classes in both treatment groups and despite similar BP values during office visits.

The main results of this analysis largely confirm and reinforce the conclusions derived from the randomized treatment period. There is no doubt that the association between VVV and outcomes in patients with well-controlled BP indicates that VVV should be considered a risk factor independently contributing to residual risk. Several hypotheses may be plausible regarding the actual meaning of increased VVV: it may be due to worse stability of treatment effect caused, for instance, by poorer adherence; it may also reflect underlying poor cardiovascular health (e.g. worse autonomic cardiovascular modulation, increased arterial stiffness, impaired renal sodium handling, or their combination).1 Whatever the explanation might be, VVV remains a parameter quite easily (and at almost no additional cost) obtained from medical records, and able to capture a considerable proportion of residual risk over and above conventional risk factors.

Several more specific aspects of the study should be emphasized. The fact that the in-trial VVV values maintained their predictive power better than average in-trial BP over a long follow-up period is new, but not really surprising: by achieving BP control with treatment, a large part of BP-related risk was removed; on the other hand, VVV is much less affected by antihypertensive treatment (especially if the correlation between BP level and VVV is adjusted for), thus leaving the associated risk largely unchanged. Notwithstanding this, the authors were able to observe long-term benefits of the amlodipine-based regimen even long after the randomized phase was completed. It is not clear whether this can be explained by persisting differences in treatment between the study arms (after 10 years in the subgroup with available data 67.2% of patients still took CCBs in the amlodipine arm and 45.6% in the beta-blocker arm) or by some kind of legacy effect (vascular ageing slowed down in the amlodipine arm?).7

Obviously, the above findings may not be considered a direct proof of the ability of long-acting CCBs such as amlodipine to reduce VVV-related risk; this would require an ad hoc trial, rather difficult to design and to implement. Nevertheless, the consistency of the data in favour of this drug class in terms of BPV lowering may suggest that, whenever the patient displays elevated BPV and has no compelling indications for other drug classes, long-acting CCBs may be the preferred choice (being safe and effective in reducing both BP and BP-related risk).

In this regard, it is interesting to consider the intriguing parallelism between the reported findings and the observations from the CAFE substudy of ASCOT. In this substudy, a much more pronounced reduction in central BP was observed in the amlodipine-based treatment arm than with the atenolol-based treatment (while peripheral BP was similar between arms). The possible contribution of this difference to the better outcomes in the former group was hypothesized, similarly as for VVV.8 It would be fascinating to explore whether the observed differences in these two BP features were inter-related and to understand their relative importance.

The incorporation of BPV in clinical practice will require a generally accepted cut-off value, which will allow patients to be divided into those with elevated or normal BPV. This will be necessary to use BPV for reclassifying individual patient’s risk, mostly in those in whom conventional risk assessment tools produce equivocal (‘borderline’) stratification. Gupta et al. identified 13 mmHg for SBP SD (the lower limit of the upper tertile of distribution in the study cohort) as the value of VVV above which the risk is clearly increased.7 Arguably, this simple approach may be a tad too simplistic. The authors did not run a formal analysis to demonstrate the validity of this threshold. Such an analysis would be of interest given that some previous studies (including ASCOT itself) suggested that the relationship between BPV and outcome may not be linear.4 Therefore, a finer categorization (e.g. in deciles) might be more efficient in capturing a meaningful threshold value. Moreover, the same threshold may not be optimal for all BP levels, since BPV (measured as the SD of BP values) is known to increase with increasing average BP. Metrics of BPV are available, such as coefficient of variation (CV) or variation independent of mean (VIM), which can largely remove the above correlation. Even though they do not appear superior to SD in statistical models which adjust for average BP, they might be preferable in individual patients, in whom such an adjustment is not possible. CV seems particularly suited to clinical use, being much easier to calculate.1 Finally, the application of finer statistical tools which evaluate the ability of the investigated indices to reclassify cardiovascular risk, such as the Net Reclassification Index and the Integrated Discrimination Index, might reinforce the impact of the present results. Until now the ability of BPV to improve risk stratification has been formally evaluated in only a few studies: significant increases in reclassification indices were reported for short-term BPV by the Ambulatory Blood Pressure-International Study,9 for home BPV in the study by Sasaki et al.,10 and for VVV in ADVANCE-ON data.11

The data from long-term ASCOT follow-up add to already solid evidence supporting BPV as an emerging risk factor, potentially able to improve risk classification and to help in explaining residual risk of hypertensive patients,7 as summarized in the recent Position Paper on BPV of the European Society of Hypertension.1 Furthermore, it appears that this factor may by modified by giving preference to long-acting CCBs in hypertension treatment, and corollary evidence suggests possible benefits of BPV lowering in terms of outcome improvement.

In this regard, BPV appears at least non-inferior to other emerging cardiovascular risk factors listed in recent international guidelines for cardiovascular prevention and hypertension management. Its association with outcomes appears as strong as that of, for example, Lp(a),12 birthweight,13 or air pollution.14 At variance from BPV, many of these factors have no formal evidence supporting their ability to reclassify risk. Moreover, accumulating evidence suggests that a specific pharmacological intervention can modify BPV. In contrast, many factors listed in the guidelines such as arterial stiffness or air pollution are not easily or not at all modifiable on an individual level.

On such a background and given the results of the study by Gupta et al.,7 the moment may thus have finally arrived to seriously consider use of BPV in clinical practice as an additional BP-related, potentially modifiable risk factor.

Declarations

Disclosure of Interest

The authors declare no disclosure of interest for this contribution.

References

Author notes

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of the European Heart Journal or of the European Society of Cardiology.