-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Artur Fedorowski, Robert Sheldon, Richard Sutton, Tilt testing evolves: faster and still accurate, European Heart Journal, Volume 44, Issue 27, 14 July 2023, Pages 2480–2482, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad359

Close - Share Icon Share

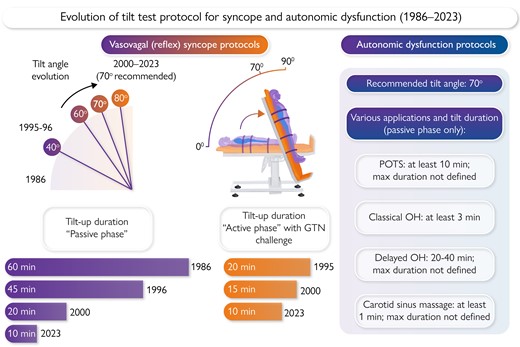

Evolution of the tilt test protocol for reflex syncope and autonomic dysfunction 1986–2023. The left side represents evolution of the tilt test protocol for reflex syncope leading to the ‘Fast Italian protocol’, and years when changes were introduced. Tilt angles have progressively increased, with 70° now being the norm. Tilt durations have progressively shortened in the passive phase, with less change in the active (drug challenge) phase, which may be at the minimum for the drug to produce its effect and for the effect to initiate reflex syncope. The figure shows centrally a tilt test being conducted. It will be noted that the intravascular blood volume shifts into the legs with upright posture. The right side summarizes applications of the tilt test for detection of cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction with tilt duration proposed by autonomic societies. GTN = nitroglycerin; POTS = postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome; OH = orthostatic hypotension.

This editorial refers to ‘Short-duration head-up tilt test potentiated with sublingual nitroglycerin in suspected vasovagal syncope: the fast Italian protocol’, by V. Russo et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad322.

In this issue of the European Heart Journal, Russo and colleagues1 report the results of a randomized trial of a considerably shortened version of the widely used Italian tilt test protocol. They compared similar test structures with the new version lasting only 20 min with the currently recommended duration of 35 min. The two test protocols performed very similarly, which offers the possibility of saving precious clinical time. The importance of this study is best understood in the context of current assessment of syncope, considering the long evolution of tilt-table testing, and the necessary diffusion of this simple and short diagnostic tool into many settings.

Syncope is a very common cardiovascular presentation. It is a symptom with a wide range of causes, results in injury in 15%, and is associated with well-documented reductions in quality of life.2 The complexity and sequelae of syncope presentations mean that there is a pressing need for simple, efficient diagnostic approaches. The most common cause of syncope is vasovagal reflex and, if the history is not diagnostic, the most sensitive and specific investigation is tilt testing. The contribution of Russo and colleagues stands to make it simpler and more widely accessible.

A recent article in the journal has shown that tilt testing in patients with syncope remains a valuable asset3 despite a shift from diagnosis to exposure of a tendency to reflex syncope.

Tilt testing as a clinical tool emerged in 1986 with a small series of unexplained syncope patients being diagnosed with vasovagal reflex by prolonged passive head-up tilt, reported by Kenny and colleagues.4 This revelation sparked its world-wide implementation. However, the first tilt test protocol, although suitable for diagnosis in the highly symptomatic, was inadequate for widespread use. The tilt angle was too low at 40° and required too long an upright period, 60 min. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, many sought modifications which included higher tilt angles up to 60–80° and shorter tilt durations, all of which have been successively adopted5,6 (Graphical Abstract). In addition, lower-body negative pressure and drug interventions (i.v. isoproterenol or sublingual nitroglycerin)7,8 designed to potentiate the effect of diminished venous return in the upright position were introduced. Isoproterenol was favoured in North America while Europe selected nitroglycerin, quickly finding it effective, with sublingual delivery obviating the need for establishing i.v. access.8 I.v. access also had a disadvantage of possible accompanying pain, polluting the autonomic atmosphere of the patient. Another aspect was that i.v. access may have, in some instances, allowed better reimbursement in the USA accompanied by the huge rise in the cost of isoproterenol, but with the outcome that tilt testing fell from favour. In this context, Sheldon9 proposed in 1993 a dramatic change in the tilt testing protocol with elimination of the passive phase and only a 10 min drug challenge using isoproterenol up to 5 μg/min. This proposal did not, however, gain wider acceptance either in North America or in Europe.

By the late 1990s to early 2000s, Europe was concentrating on sublingual nitroglycerin and tilt testing was in decline in theUSA. At this point, the ‘Italian protocol’ with a moderate 20 min passive tilt period followed by a 15 min drug intervention period with sublingual nitroglycerin was published10 and adopted by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines in 2001 and all subsequent iterations to the present version issued in 2018.2

The ‘Italian protocol’ is still lengthy and now is challenged by the Russo group1 who have approached further shortening of the test by reduction of the passive phase to 10 min made on a scientific basis (Graphical Abstract). Russo and colleagues examined equal groups (n = 277 in each) of patients with unexplained syncope using the traditional (i.e. longer) and the fast (shortened) Italian protocol, demonstrating almost the same rate of positive responses (58.5% vs. 60.3%). These authors conclude that their ‘Fast Italian’ protocol may safely replace the traditional one, and it is difficult not to agree with them as the modified protocol may save a lot of time in the tilt laboratory.

Russo’s group has made an important step1 which is expected to be widely adopted. If this happens, patients benefit, with more cases being diagnosed; is the expectation further strengthened by our new understanding of reflex syncope that has accumulated in recent years? The enlightenment was, perhaps, triggered by the ‘Reinterpretation of tilt testing’ in 201411 and has been followed by the identification of a low blood pressure (BP) phenotype prone to sustain a positive tilt test12 and demonstration of asymptomatic episodes of hypotension in these patients, offering a further test by ambulatory BP monitoring to confirm the patient’s susceptibility to reflex syncope.13

Vasovagal reflex is the most common syncope aetiology, but almost all subsequent deaths of syncope patients are due to a wide variety of cardiovascular problems. Only 5–10% of diagnosed aetiologies are related to cardiac arrhythmias. In many countries, care is centred in syncope units, use of the Italian protocol is high, and the abbreviated Russo protocol will further streamline care. In countries in which care for syncope patients tends to be directed towards arrhythmia specialists, who are primarily focused on arrhythmia detection, ablation, and devices, with less focus on non-cardiac syncope, adoption of the Fast Italian protocol might be a potential ‘game changer’.

The shortened protocol is sufficiently easy, safe, non-invasive, inexpensive, and well tolerated that it could be implemented in most clinics, requiring less infrastructure than a stress test. Early use of this protocol might reduce the need for expensive implantable loop recorders. In countries with less established syncope units, this might significantly expand the number of treating physicians, who would use it simply as another diagnostic test. This would change the paradigm completely, from highly specialized and few syncope specialists, to numbers more able to meet the diagnostic demand. Syncope assessment could become generalized, moving out of large referral sites to the community—a pattern demonstrated repeatedly for successful and valuable medical procedures. Moreover, one standardized methodology would facilitate international collaboration and multicentre studies, so desperately needed for an effective reflex syncope treatment.

The shortening of the protocol by the Russo group rightly focuses on syncope diagnosis, of course after a clinical history. Its wide acceptance may generate a need for different protocols: one for patients with a history of unexplained syncope and high likelihood of reflex mechanism, and another for orthostatic intolerance with underlying cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction but without history of syncope (Graphical Abstract). The latter includes common dysautonomic conditions such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome and orthostatic hypotension, especially the delayed (slowly progressing) form,14 where an active standing test may be impractical, inconclusive, or imprecise to confirm the diagnosis.3 The details of this potential second tilt protocol have yet to be clarified, but prolonged passive upright tilt may be needed if the haemodynamic changes demonstrate an obvious tendency without meeting the pre-defined diagnostic criteria of autonomic dysfunction. For some patients, the volume shift produced by tilt testing (Graphical Abstract) may be slower to develop as their compensatory mechanisms are more effective, justifying prolonged orthostatic challenge for correct diagnosis. Finally, we should bear in mind that tilt testing might be applied as a part of a more comprehensive cardiovascular autonomic workup and can augment the effects of other provocatory tests such carotid sinus massage, Valsalva manoeuvre, or deep breathing test, as recommended by the current European syncope guidelines and autonomic societies.2,15 For the syncope protocol, these additions may be unnecessary, unless a comprehensive autonomic workup is indicated by the patient’s history and/or the referring physician’s request.

The study has some limitations. It was performed in two centres only and was underpowered to tease out the effects of age, sex, and baseline syncope burden, which might be important. In the absence of a healthy control group, there remains the theoretical possibility that the specificity of the short protocol is less than that of the standard Italian protocol. These aspects should be addressed by further studies.

In closing, the Russo group is to be applauded for this work, which is expected to be widely adopted in Europe. It may also encourage a wider use of the shortened tilt test protocol in other parts of the world and change the delivery of syncope assessment and care. If this happens, patients will benefit and the pressure on large referral centres might even subside. A worthwhile step indeed.

References

Author notes

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of the European Heart Journal or of the European Society of Cardiology.

Conflict of interest A.F. is a consultant to Medtronic Inc., ArgenX BV, and Antag Therapeutics, and has received lectures fees from Finapres Medical Systems. R.Sh. has no conflicts to declare. R.Su. is a consultant to Medtronic Inc. and a member of the Speakers bureau of Abbott Laboratories Corp (SJM).