-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jasper Tromp, Adriaan A Voors, Heart failure medication: moving from evidence generation to implementation, European Heart Journal, Volume 43, Issue 27, 14 July 2022, Pages 2588–2590, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac272

Close - Share Icon Share

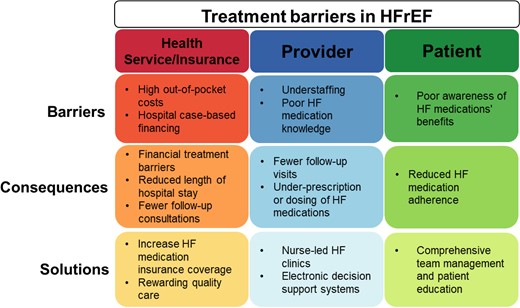

Overview of possible treatment barriers, consequences, and solutions for optimizing HFrEF pharmacotherapy. Abbreviations: HF, heart failure; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

This editorial refers to ‘Accelerated and personalized therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction’, by L. Shen et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac210.

Treating patients with heart failure (HF) and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) with renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors, beta-blockers, and sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors at guideline-recommended dosages (GRD) improves quality of life and increases longevity.1,2 Early European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommended a stepwise strategy to treatment initiation and up-titration.3,4 This strategy started with initiation and up-titration of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and beta-blockers followed by symptom- and left ventricular ejection fraction- (LVEF) guided initiation of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) or ivabradine, or replacing ACE inhibitors with an angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor (ARNi);3 effectively tracking a chronological order of trials to initiate therapies. However, stepwise initiation and up-titration of HF medication can take months, costing considerable time, resources, and potential life years saved. Furthermore, the demonstrated early treatment benefits of ARNis and SGLT2 inhibitors upended this old strategy, leading to the recent 2021 guidelines recognizing ACEi/ARNi, beta-blockers, MRAs, and SGLT2 inhibitors as the ‘foundational 4’ therapies. Yet, the 2021 guidelines failed to give clear guidance on whether HF pharmacotherapies should be initiated simultaneously or in what sequence,1 leaving practising physicians with a significant conundrum. Simultaneous initiation of quadruple therapy might solve the problem. However, this will inevitably increase the risk of side effects, which will be challenging to link to individual medications.

In this issue of the European Heart Journal, Shen et al. significantly extend existing evidence on the benefits of different therapy sequencing strategies in patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).5 The authors estimated the potential reduction of events within 12 months according to different treatment sequences, starting with initiating one or two medications. The authors modelled the events possibly prevented using the combined treatment-naïve placebo arms of the SOLVD-Treatment and CHARM (Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity)-Alternative trials and previously reported hazard ratios from landmark clinical trials. They found that alternative ways of sequencing therapies can potentially reduce the number of HF hospitalizations or cardiovasascular (CV) deaths by up to 47.3 per 1000 person-years. Sequences starting with an SGLT2 inhibitor, MRA, or both were associated with the most significant reduction in CV death, HF hospitalization, and all-cause death. Notably, up to half of the reduction in events was primarily attributed to shortening the time to reach target dose. This might partially explain why sequences starting with medications with fewer up-titration steps (i.e. SGLT2 inhibitors or MRAs) were associated with the most significant reduction in events.

The authors need to be commended for their work, which provides important new insights into the potential benefits of alternative treatment sequencing strategies. Strengths of the study include using two large, well-characterized treatment-naïve populations to estimate the possible number of reduced events and the extensive modelling of various clinically relevant treatment combinations. The study also has several limitations, which deserve mention. First, the authors modelled best-case scenarios where patients can tolerate all medications. ‘Real-world’ patients are commonly older and have more comorbidities, often leading to discontinuation of HF medications.6–9 For example, the mean age of patients in the placebo arm of SOLVD-Treatment was only 61 years,10 compared with 64 years in the ESC HF Long-term registry11 or 71 years in SWEDE-HF.12 Therefore drug discontinuation will probably be higher in real-world patients, and it is unclear how realistic some of the rapid up-titration schedules are in clinical practice. Second, many patients with new-onset HF will be on existing ‘HF’ medication for pre-existing comorbidities such as diabetes or hypertension, which will reduce the derived treatment benefits. Third, the authors did not model the uncertainty of treatment effects and assumed that treatment effects were multiplicative. The assumption of additive drug effects seems reasonable because different HF medications largely target different pathophysiological pathways.13 Nevertheless, this assumption introduces uncertainty in the estimates. Lastly, while scenarios involving the initiation of two medications simultaneously accounted for the risk of discontinuation of individuals drugs, actual discontinuation rates might be higher when side effects cannot be attributed to single medications, leading to possible discontinuation of both. An alternative solution might be the sequential initiation of multiple individual medications at low doses and subsequent up-titration to target doses of individual medications.

Notwithstanding the limitations, the study by Shen et al.5 provides compelling data to consider alternative sequential treatment strategies in HFrEF. Two previous studies showed that the ‘foundational 4’ can extend life by 5.0 years in a 70 year old.2 The present study shows that alternative and more rapid therapy sequencing strategies can save lives already within the first year of treatment. Unfortunately, despite the clear benefits of HF therapies, results from European, North American, and global registries highlight that many patients with HFrEF are still undertreated or treated at suboptimal medication doses.6,8,9 Clinical characteristics and possible side effects have only partially explained the significant treatment gaps in patients with HFrEF. Instead, ‘clinical inertia’ and an underappreciation of clinical risk, particularly in patients with few signs and symptoms, might play an important role. However, ‘clinical inertia’ is an elusive concept more likely to be reflecting underlying structural issues such as high medication co-payments, staffing shortages, or poor physician and patient education on the benefits of HF pharmacotherapy. Therefore, closing HFrEF treatment gaps requires a renewed focus on implementing strategies addressing these underlying barriers (Graphical Abstract). For example, including treatment quality metrics as instruments for financing HF care can incentivize hospitals to prioritize the quality of pre- and post-discharge care over reducing the length of stay. Task-shifting HF care and outpatient follow-up to trained HF nurses can reduce the impact of staffing shortages. Results from Sweden showed that nurse-led HF clinics were associated with lower mortality risk and an increased likelihood of patients being on guideline-directed medical therapy.14 Comprehensive team management and patient education on HF medication’s potential benefits, side effects, and expectations can improve adherence and reduce discontinuation.15 New digital tools, such as electronic decision support tools, can support non-specialist healthcare practitioners to optimize HF medication. For example, a recent cluster randomized trial in the USA showed that a clinical decision support system could improve adherence to guideline-recommended treatment for HF in primary care.16 The results of the study by Shen et al. provide further support for the fact that there is little room for ‘clinical inertia’, and delays in rapid initiation and up-titration of HF medical therapy can cost lives. Future studies should identify context-specific health system barriers underlying ‘clinical inertia’ to implement effective strategies to improve HF medication use.

In conclusion, Shen et al.’s study provides compelling evidence on using alternative treatment strategies to reduce the time to initiate and up-titrate HF pharmacotherapy. Importantly, their results emphasize the need for quick but responsible initiation and up-titration of the ‘foundational 4’ therapies in patients with HFrEF and new implementation strategies to facilitate this.

Conflict of interest: J.T. is supported by the National University of Singapore Start-up grant, the tier 1 grant from the ministry of education, and the CS-IRG New Investigator Grant from the National Medical Research Council; has received consulting or speaker fees from Daiichi-Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche diagnostics, and Us2.ai; and owns patent US-10702247-B2 unrelated to the present work. A.A.V. has received research support and/or has been a consultant for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer AG, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, Merck, Myokardia, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, and Roche Diagnostics.

References

Author notes

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of the European Heart Journal or of the European Society of Cardiology.