-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Abigail D Khan, Anne Marie Valente, Don’t be alarmed: the need for enhanced partnerships between medical communities to improve outcomes for adults living with congenital heart disease, European Heart Journal, Volume 42, Issue 41, 1 November 2021, Pages 4249–4251, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab281

Close - Share Icon Share

This editorial refers to ‘Lack of specialist care is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in adult congenital heart disease: a population-based study’, by G-P. Diller et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab422.

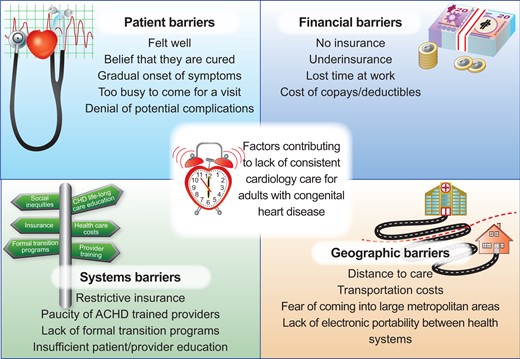

Summary of common barriers to appropriate adult congenital heart disease care.

Over the last few decades, the worldwide population of adults living with congenital heart disease (CHD) has grown substantially.1 , 2 Adults living with CHD are a complex, heterogeneous group of patients with a significant risk of adverse health outcomes in spite of dramatic improvements in medical and surgical care.2 Despite an increasing body of literature supporting the importance of timely, evidence-based medical care, many adult congenital heart disease (ACHD) patients see a cardiologist too late or not at all. There are numerous barriers to receiving ACHD care,3 and surmounting these barriers will require systems-level innovation (Graphical Abstract). Obtaining evidence of the objective benefit of specialized care is a key step in convincing hospitals, health insurers, and other stakeholders to invest the necessary resources to develop robust systems of ACHD care.

In this issue of the European Heart Journal, Diller et al. 4 are asking a critically important question in the field of ACHD: does cardiology follow-up result in a quantifiable improvement in patient outcomes? In this study, the authors used an administrative dataset from a large German health insurer to determine if ACHD patients who were seen by a cardiologist had a lower incidence of major adverse outcomes, including mortality. The major findings of this study are three-fold: (i) 50% of ACHD patients in the dataset were not seen by a cardiologist during the 3-year study period; (ii) the vast majority of patients had contact with either a primary care provider (PCP) or a cardiologist, suggesting that the problem was not loss of contact with the healthcare system; and (iii) the risks of death and major adverse events were lower in those patients who were in cardiology care.

Diller et al. 4 evaluate the impact of specialty vs. primary care as it relates to outcomes in ACHD patients and describe these findings as ‘alarming data’. We agree that the results are provocative, particularly as this dataset is from an insured population in a country with an organized system of ACHD care. They suggest that, despite more than a decade of practice guidelines advocating for the central role of ACHD specialists , 5 nearly half of the patients are not receiving regular cardiology care. These findings reinforce the need to identify and address the barriers that exist for ACHD patients to receive appropriate care.

There are inherent limitations of administrative data which should be noted when interpreting the results of this study. Billing codes are only moderately accurate in identifying adults with CHD, and lack granularity with respect to prior surgical repairs and physiological status.6 Administrative datasets are not generally designed for research purposes, and so are better suited for the examination of population-level trends than to provide an in-depth understanding of individual patient outcomes. Importantly, they only include patients with access to healthcare, and thus may fail to illustrate important inequities. Notably, Diller et al. did not provide information about racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic differences in access to cardiology care. We are no longer a nascent field and it is our responsibility to attempt to understand the full breadth of challenges faced by ACHD patients, including social inequities.

Patients who choose to present to cardiac care represent a self-selected group that may differ in a variety of ways, including their knowledge about their health, the resources at their disposal, and their ability to comply with recommended care. In the absence of a randomized study, which is not morally feasible, we are left to consider the impact of patient vs. provider factors on both rates of access to cardiac care and downstream adverse healthcare outcomes. Administrative datasets, while helpful, are not ideally suited to understanding the drivers of patient and provider decision-making, and therefore are not sufficient as a stand-alone resource to understand the challenges of long-term ACHD care.

The authors estimate that at 3 years of follow-up in their sample, the absolute risk of mortality was 0.9% higher in patients with moderate to severe CHD who were not seen by a cardiologist. This finding is especially striking given that the cardiology patient population had a higher disease complexity and a significantly greater burden of comorbidities than the population seen only by a PCP. Not surprisingly, in univariate models, those in cardiology care had a higher risk of adverse outcomes, but, after multivariable adjustment including the use of propensity scores, that risk was lower. The finding that cardiologists achieve better outcomes despite caring for a higher risk patient population is notable, but not surprising, given data showing higher rates of guideline-directed medication use by cardiologists as compared with PCPs.7 Another mechanism by which cardiologists could impact outcomes is by timely, appropriate referral for advanced imaging and cardiovascular interventions. Both guideline non-adherence and late referral to intervention are common in ACHD and, interestingly, may be more common in patients seen by non-ACHD-trained cardiologists.8 Importantly, it should be noted that the manuscript by Diller et al. is not endorsement of ACHD-specific care, as the authors could not statistically separate the effect of general and ACHD cardiologists. While one might imagine based on prior data that ACHD-specific care may be superior, this has yet to be validated in multiple populations.8 , 9

This study is a high-level examination of rates of adverse outcomes and not an in-depth analysis of mechanisms and causes. The authors do not provide, for instance, causes of death in order to determine how many were preventable, and specifically how many were due to cardiovascular disease. Interestingly, they found that cardiology follow-up was associated with decreased mortality in women, but not in men, in the sample. The mechanism of this is unknown, but given known sex-based differences in the treatment and outcomes of cardiovascular disease, further work is needed to understand sex-specific differences in ACHD.10

The authors’ findings underscore the degree to which loss to follow-up continues to limit our ability to deliver appropriate care to ACHD patients. Lack of follow-up remains a persistent problem despite a strong focus on programmatic growth and the development of coordinated transition programmes. While the current analysis does not help elucidate the underlying contributors to this problem, it does provide an important measure of the problem’s scope. The findings are consistent with previous analyses showing high rates of loss to follow-up in ACHD.3 , 11 , 12 Notably, in the current study, lack of insurance and/or complete lack of contact with the healthcare system are not the barriers, as has been postulated in previous studies. Therefore, it is important to search for other barriers to consistent and appropriate ACHD care.

The authors point to a lack of referral to cardiac care by PCPs, emphasizing the point that 49% of patients were seen only by a PCP during the study period. As presented, the data do not differentiate between lack of referral by PCPs and lack of attendance at a cardiology clinic by patients, which is an important point, given that patients may fail to schedule and/or show at appointments for a variety of reasons. While it is easy to interpret these data as an indictment of PCP care, we should exercise extreme caution in interpreting them as such without better understanding the primary care perspective. A significant number of ACHD patients experience multiorgan dysfunction, and the primary care clinician’s role is essential for coordinated care.

Much of the literature addressing loss of care in ACHD focuses on patient education and the need for patients to act as advocates for their healthcare. Progress will also be made by provider education to promote lifelong care of patients living with CHD. Education alone, however, is unlikely to be sufficient. Referral pathways should be seamless, access to ACHD care must be equitable, and there should be a closed loop communication stream between the specialist and the PCP. Perhaps most importantly, the relationship between the ACHD specialist and the PCP should be viewed as a partnership, with both individuals playing an essential and impactful role in the patient’s health. While the optimal model of collaborative ACHD care has yet to be defined, it is clear that the future outcomes of this population hinge on the ability of our specialty to work closely with other healthcare providers. Future work should examine the potential role of innovative care models, such as shared visits, electronic visits, and others.

The authors also demonstrate a decrease in major adverse events, including emergency hospital admission, in the patients in recent cardiology care. While psychosocial metrics, including quality of life, are not measurable in an administrative dataset, it seems reasonable to postulate that a decrease in adverse events would translate into improvement in quality of life. That said, for some patients, a greater quantity of life does not translate into a better quality of life. These trade-offs should not be forgotten as we attempt to define the value of ACHD care.

It is clear that cardiology care matters for adults living with CHD. The next step for us all is to take this message forward, educating providers, empowering patients, and developing better care networks to support this growing population of individuals with complex care needs.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of the European Heart Journal or of the European Society of Cardiology.

References