-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Filippo Crea, Challenges in heart failure: quality of life, chronic kidney disease, and secondary mitral regurgitation, European Heart Journal, Volume 42, Issue 13, 1 April 2021, Pages 1185–1189, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab154

Close - Share Icon Share

For the podcast associated with this article, please visit https://dbpia.nl.go.kr/eurheartj/pages/Podcasts.

For the podcast associated with this article, please visit https://dbpia.nl.go.kr/eurheartj/pages/Podcasts.

This Focus Issue on heart failure (HF) and cardiomyopathies opens with the Viewpoint entitled ‘The Dapagliflozin And Prevention of Adverse outcomes in Heart Failure trial (DAPA-HF) in context’, authored by John McMurray from the University of Glasgow in the UK, and colleagues.1 The authors note that the recently reported Dapagliflozin And Prevention of Adverse outcomes in Heart Failure trial (DAPA-HF) showed that the sodium–glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin reduced the risk of hospital admission for worsening HF, increased survival, and improved symptoms in patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). In addition, the beneficial effects of SGLT2 inhibitors are not diminished in intensively treated patients who are receiving sacubitril/valsartan.2,3Although SGLT2 inhibitors had been developed as glucose-lowering treatments for patients with type 2 diabetes, approximately half of the patients in DAPA-HF did not have type 2 diabetes. The benefits of dapagliflozin in DAPA-HF were of a similar magnitude in participants without diabetes to those obtained in individuals with diabetes. The authors put these findings into perspective, indicating that there are two principal contextual considerations: (i) how the patients randomized in DAPA-HF and their event rates compare with those in previous SGLT2 inhibitor trials; and (ii) how the effects of dapagliflozin compare with those of other pharmacological treatments for HFrEF.

Besides the risk for mortality and recurrent hospitalizations, patients with HFrEF also suffer from impaired health status. Improvements in physical functioning and symptoms constitute major treatment goals in these patients, as reflected by the guidance statements from regulatory agencies and the recognition of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) and the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire by the Food and Drug Administration as a clinical trial endpoint. The effects of SGTL2 inhibitors on quality of life are still poorly known.4 In a clinical research article on their secondary analysis of the EMPEROR-Reduced trial entitled ‘Empagliflozin and health-related quality of life outcomes in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the EMPEROR-Reduced trial’, Javed Butler from the University of Mississippi School of Medicine, Jackson, MS, USA, and colleagues sought to evaluate whether the benefits of empagliflozin varied by baseline health status and how empagliflozin impacted patient-reported outcomes in patients with HFrEF.5 Health status was assessed by the KCCQ clinical summary score (KCCQ-CSS). The influence of baseline KCCQ-CSS (analysed by tertiles) on the effect of empagliflozin on major outcomes was examined using Cox proportional hazards models. Responder analyses were performed to assess the odds of improvement and deterioration in KCCQ scores related to treatment with empagliflozin. Empagliflozin reduced the primary outcome of cardiovascular (CV) death or HF hospitalization regardless of baseline KCCQ-CSS tertiles. In addition, empagliflozin improved KCCQ-CSS, total symptom score, and overall summary score at 3, 8, and 12 months. Finally, more patients on empagliflozin had more than a 5-point [odds ratio (OR) 1.20], 10-point (OR 1.26), and 15-point (OR 1.29) improvement at 3 months. These benefits were sustained at 8 and 12 months.

The authors conclude that empagliflozin improves CV death or HF hospitalization risk across the range of baseline health status and improves health status across various domains during long-term follow-up. The manuscript is accompanied by an Editorial by John Spertus from Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute and the University of Missouri–Kansas City in Kansas City, MO, USA, and colleagues.6 Spertus and colleagues conclude that the report by the EMPEROR-Reduced investigators provides much-needed information to patients and providers about an important benefit of therapy. While there are additional methods to render the findings even more clinically interpretable and to eventually build risk models to help identify which patients are most likely to benefit from empagliflozin, it is increasingly clear that SGLT2 inhibitors can improve the symptoms, function, and quality of life of patients with HFrEF. The key challenge now is for the provider community to develop new strategies to treat and engage their patients in using these treatments so that their health status and clinical outcomes can be improved.

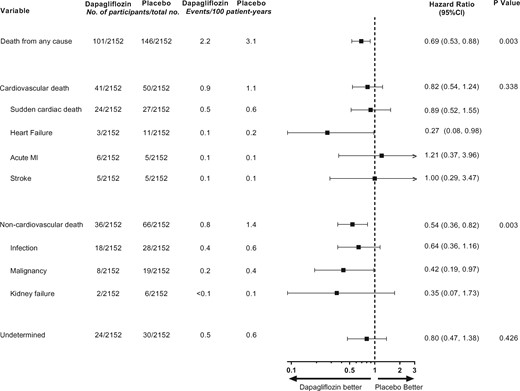

Mortality rates attributed to chronic kidney disease (CKD) have increased in the last decade.7 SGLT2 inhibitors delay progression to kidney failure in patients with type 2 diabetes, both at the early and at more advanced stages of CKD. These benefits appear independent of the improvements in glycaemic control and are likely to be mediated by other mechanisms including favourable effects on glomerular haemodynamics. These findings have led to the hypothesis that SGLT2 inhibitors may also preserve kidney function in patients with CKD without type 2 diabetes. The DAPA-CKD trial enrolled patients with CKD with and without type 2 diabetes and demonstrated that dapagliflozin significantly reduced the risk of kidney events, hospitalizations for HF or CV death, and prolonged survival irrespective of type 2 diabetes status.8 In a clinical research article entitled ‘Effects of dapagliflozin on mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: a pre-specified analysis from the DAPA-CKD randomized controlled trial’, Hiddo Lambers Heerspink from the University Medical Center Groningen in the Netherlands, and colleagues determined the effects of dapagliflozin on CV and non-CV causes of death in a pre-specified analysis of the DAPA-CKD trial.9 DAPA-CKD was an international, randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a median 2.4 years follow-up. Eligible participants were adult patients with CKD, defined as a urinary albumin to creatinine ratio of 200–5000 mg/g and an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 25–75 mL/min/1.73 m2. All-cause mortality was a key secondary endpoint. CV and non-CV death was adjudicated by an independent clinical event committee. The DAPA-CKD trial randomized participants to dapagliflozin 10 mg/day or placebo. The mean age was 62 years, 33% were women, and mean eGFR was 43.1 mL/min/1.73 m2. During follow-up, 247 (5.7%) patients died: 37% of patients died due to CV causes and 41% due to non-CV causes, while in 22% of patients the cause of death was undetermined. The relative risk reduction for all-cause mortality with dapagliflozin (hazard ratio 0.69; P = 0.003) was consistent across pre-specified subgroups. The effect on all-cause mortality was driven largely by a 46% relative risk reduction of non-cardiovascular mortality (Figure 1). Deaths due to infections and malignancies were the most frequently occurring causes of non-CV deaths, and were reduced with dapagliflozin vs. placebo.

Effect of dapagliflozin on cardiovascular, non-cardiovascular, and undetermined causes of deaths (from Sjöström CD, Jongs N, Chertow GM, Kosiborod M, Hou FF, McMurray JJV, Rossing P, Correa-Rotter R, Kurlyandskaya R, Stefansson BV, Toto RD, Langkilde AM, Wheeler DC; for the DAPA-CKD Trial Committees and Investigators. Effects of dapagliflozin on mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: a pre-specified analysis fromthe DAPA-CKD randomized controlled trial. See pages 1216–1227).

The authors conclude that in patients with CKD, dapagliflozin prolongs survival irrespective of baseline patient characteristics. The benefits are driven largely by reductions in non-CV death. The manuscript is accompanied by an Editorial by Nikolaus Marx from the University Hospital in Aachen, Germany10 who notes that taken together, the data from DAPA-CKD, in conjunction with the results from other recently published SGLT2 inhibitor trials in patients with HFrEF, position the class of SGLT2 inhibitors far beyond their original use in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) is an inherited disease associated with a high risk of sudden cardiac death.11–13 Among other factors, physical exercise has been clearly identified as a strong determinant of the phenotypic expression of the disease, arrhythmic risk, and disease progression. Because of this, current guidelines advise that individuals with ARVC should not participate in competitive or frequent high-intensity endurance exercise.14 In a State of the Art Review article entitled ‘Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and sports activity: from molecular pathways in diseased hearts to new insights into the athletic heart mimicry’, Alessio Gasperetti from the University Heart Center Zurich in Switzerland, and colleagues further discuss this subject.15 Exercise-induced electrical and morphological para-physiological remodelling (the so-called ‘athlete’s heart’) may mimic several of the classic features of ARVC. Therefore, the current International Task Force Criteria for disease diagnosis may not perform as well in athletes. Clear adjudication between the two conditions is often a real challenge, with false positives, which may lead to unnecessary treatments, and false negatives, which may leave patients unprotected, both of which are equally unacceptable. This review aims to summarize the molecular interactions caused by physical activity in inducing cardiac structural alterations, and the impact of sports on arrhythmia occurrence and other clinical consequences in patients with ARVC, and to help the physicians in setting the two conditions apart.

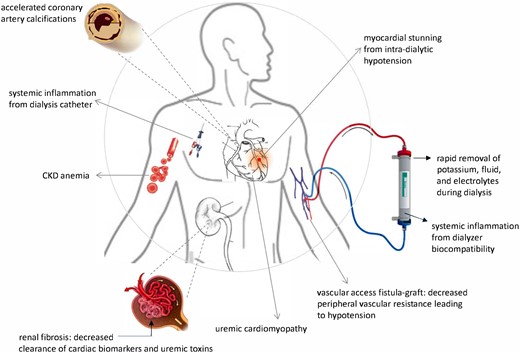

CKD patients require dialysis to manage the progressive complications of uraemia, yet many physicians and patients do not recognize that dialysis initiation, although often necessary, subjects patients to substantial risk for CV death.16,17 In a State of the Art Review article entitled ‘The cardiovascular–dialysis nexus: the transition to dialysis is a treacherous time for the heart’, Kevin Chan from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease in Bethesda, MD, USA, and colleagues indicate that while most recognize that CV mortality risk approximately doubles with CKD, the recent data presented in their review show that this risk spikes to >20 times higher than the US population average at the initiation of chronic renal replacement therapy, and this elevated CV risk continues through the first 4 months of dialysis. Moreover, this peak reflects how dialysis itself changes the pathophysiology of CV disease and transforms its presentation, progression, and prognosis.18 This article also reviews how dialysis initiation modifies the interpretation of circulating biomarkers, alters the accuracy of CV imaging, and worsens prognosis (Figure 2). The authors advocate a multidisciplinary approach and outline the issues practitioners should consider in order to optimize CV care for this unique and vulnerable population during a perilous passage.

The mechanisms of cardiovascular disease shift when dialysis starts. (from Chan K, Moe SM, Saran R, Libby P. The cardiovascular-dialysis nexus: the transition to dialysis is a treacherous time for the heart. See pages 1244–1253)

Moderate or severe secondary (also known as functional) mitral regurgitation (SMR) accompanies HF in about a third of patients and contributes to clinical deterioration, progression of the syndrome, and adverse outcomes.19,20 In a Special Article entitled ‘The management of secondary mitral regurgitation in patients with heart failure. A joint position statement from the Heart Failure Association (HFA), European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI), European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), and European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) of the ESC’, Andrew Coats from Sydney University in Australia, and colleagues note that SMR results from left ventricular remodelling that prevents coaptation of the valve leaflets. SMR contributes to progression of the symptoms and signs of HF, and confers worse prognosis.21 The management of HF patients with SMR is complex and requires timely referral to a multidisciplinary Heart Team. Optimization of pharmacological and device therapy according to guideline recommendations is crucial. Further management requires careful clinical and imaging assessment, addressing the anatomical and functional features of the mitral valve and left ventricle, overall HF status, and relevant comorbidities. Evidence concerning surgical correction of SMR is sparse, and it is doubtful whether this approach improves prognosis. Transcatheter repair has emerged as a promising alternative, but the conflicting results of current randomized trials require careful interpretation. This collaborative position statement, developed by four key associations of the European Society of Cardiology—the Heart Failure Association, European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions, European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging, and European Heart Rhythm Association—presents an updated practical approach to the evaluation and management of patients with HF and SMR based upon a Heart Team approach.

The issue is also complemented by a Discussion Forum contribution. In an article entitled ‘Different genotypes of Brugada syndrome may present different clinical phenotypes: electrophysiology from bench to bedside’, Ibrahim El-Battrawy from the University of Heidelberg in Germany, and colleagues comment on the recent publication entitled ‘Brugada syndrome genetics is associated with phenotype severity’ by Giuseppe Ciconte from the IRCCS Policlinico San Donato in Milan, Italy, and colleagues.22,23 Ciconte and colleagues respond in a separate contribution.24

The editors hope that this issue of the European Heart Journal will be of interest to its readers.

With thanks to Amelia Meier-Batschelet, Johanna Huggler, and Martin Meyer for help with compilation of this article.

References

Coats AJS, Anker SD, Baumbach A, Alfieri O, von Bardeleben RS et al