-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tomasz Górny, Arnaud du Sarrat and the international music trade in Halle and Leipzig c.1700, Early Music, Volume 51, Issue 3, August 2023, Pages 451–460, https://doi.org/10.1093/em/caad035

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Arnaud du Sarrat is known primarily as a bookseller and publisher based in Berlin, where he worked as Estienne Roger’s official agent from 1706 at the latest. This article, however, focuses on his activity in Halle between 1694/5 and 1702, when he was bookseller and bookbinder to the university. An analysis of four catalogues presents insights into the printed music available in his stores in Halle and Leipzig at the turn of the 18th century. A study is made of du Sarrat’s relationship with the Dutch book market, especially with booksellers from Amsterdam; and du Sarrat’s correspondence with Theophilus Dorrington suggests how Pietist networks also allowed for the transmission of books.

The dissemination of Italian and French music in German-speaking lands around 1700 was crucial for spreading new musical ideas and forms that shaped the development of the musical language of the late Baroque. Relatively well known is the role of manuscript copies made or assembled by musicians themselves, such as the collection of the Dresden court musician Johann Georg Pisendel. Less well known is the role of the established book trade in Central Europe, whereby agents and booksellers distributed music among many other types of books. This article investigates the music disseminated via a small, but very interesting, part of the book trade, namely the activity of Arnaud du Sarrat in Halle and Leipzig.

Du Sarrat was a bookseller, bookbinder and publisher known primarily for his activity in Berlin, where he took over the business of Robert Roger in late 1702.1 Since 1706 at the latest, du Sarrat was an official agent of the Amsterdam music publisher Estienne Roger.2 This is known from the advertisement appended to the 1706 edition of Recueil de diverses dernieres heures edifiantes by Pierre de la Roque:

It is hereby announced to all lovers of music that a large selection of it can be purchased at Estienne Roger’s establishment in Amsterdam … The same musical books can also be had in London from booksellers François and Paul Vaillant and in Berlin from A[rnaud] du Sarrat.3

Du Sarrat is also listed as Roger’s official agent in Berlin in the catalogues of musical works of the Amsterdam bookseller for the years 1708, 1712 and 1716,4 as well as in adverts from 1709 and 1710.5 This article, however, focuses on an earlier, virtually unknown period of du Sarrat’s activity in Halle around 1700. At this time, printing and the book trade were rapidly developing in Halle as a result of the founding of its university and the growth of the Pietist movement led by August Hermann Francke. The current article offers new evidence of du Sarrat’s arrival in Halle, identifies the music listed in four of his catalogues, and comments on his possible connections within religious networks and within the music trade.

Arnaud du Sarrat in Halle

The archive of the Martin-Luther-Universität in Halle-Wittenberg holds two documents that shed light on Arnaud du Sarrat’s early days in Halle. These are copies of edicts made by the administration of the elector Friedrich III of Brandenburg (later Friedrich I of Prussia) in 1694, the year when the elector founded the university. The first document, signed on 12 September 1694 in Cölln an der Spree, is addressed to the board of the newly founded university in Halle. It identifies du Sarrat as a Frenchman from Berlin, who had received permission to settle in Halle and become the bookseller and bookbinder to the university:

The French bookseller and bookbinder Arnaud du Sarrat presented to His Grace the Duke and Elector of Brandenburg a legal proof of having mastered this valuable and revered craft; as he expressed his intention to move from here to Halle and settle there, His Grace granted him leave to do so and named him the university bookseller and bookbinder...6

The edict closes with a request that du Sarrat is welcomed in Halle and provided with accommodation for two years. The other edict, written on 12 October of the same year, indicates that the university board had not yet considered the proposal to appoint du Sarrat as the official bookseller and bookbinder, and this delay led Friedrich III to issue a direct order in his favour.7 Based on this information, we can assume that du Sarrat started operating in Halle in late 1694 or in early 1695, given that it would have taken several weeks or months to secure the premises and stock.

Du Sarrat’s French and Berlin connections suggest that he might have been one of the French Huguenots, who suffered religious discrimination in their home country after the Edict of Fontainebleau of 1685. In the same year, Elector Friedrich Wilhelm of Brandenburg proclaimed the Edict of Potsdam, granting the French refugees numerous privileges such as the right to settle, the right to worship in French, and preferential tax rates. As a result, a large contingent of Frenchmen—merchants, artisans and intellectuals—settled in Berlin.8 Halle had been depopulated in the Thirty Years’ War so it also welcomed a large diaspora of French-speaking settlers. They conducted their worship in the local cathedral, where the young George Frideric Handel served as organist in 1702–3.9 Du Sarrat, a Frenchman trading in French books most likely tailored his offer to the needs of university professors and students and also the Huguenots living in Halle, although familiarity with French language and culture was expected across European elites at this time.

Music in du Sarrat’s catalogues

Four catalogues survive from du Sarrat’s time in Halle, identified as Catalogues A to D in the discussion below. A small quantity of music is listed in each catalogue, showing how he imported music in a variety of genres from Amsterdam and possibly other locations.

Catalogue A is preserved in the British Library:10

LIVRES FRANCOIS. Qui se trouvent ches ARNAUD DUSARRAT Libraire à Halle.

French books that can be found at Arnaud du Sarrat, a bookseller in Halle.

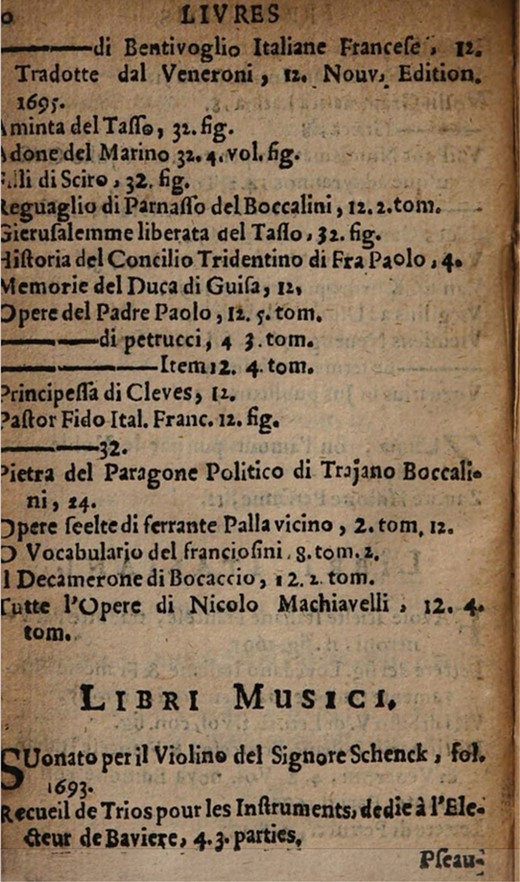

The catalogue consists of five sections. The first (pp.1–59) lists mostly French titles plus a few Latin ones, on various topics including theology, philosophy, law, medicine, chemistry, history and fiction. There are also dictionaries, several editions of the Bible, and even cookbooks. Between brief lists of Italian books (pp.59–60) and Spanish books (p.61) is a section devoted exclusively to music books (Libri musici, pp.60–1; see illus.1). The final section of the catalogue lists ‘Books that can be found in Cologne at Pierre Marteau’s’ (pp.[62]–[67]).11 Pierre Marteau (or Peter Hammer) was a fictitious name used by 17th- and 18th-century publishers and booksellers who wished to conceal their involvement in scurrilous or controversial publication.12 In this case, the ‘Pierre Marteau’ section features titles such as ‘Intrigues amoureuses de la Cour de France’ (Amorous intrigues of the French court) or ‘Catéchisme des Courtisans’ (Catechism of the courtesans).13 Only the final note of the section serves to remind the reader that they are still perusing a du Sarrat catalogue.14 The catalogue is not dated; it does, however, feature many items published in 1694 and 1695, and several dozen dated to 1696 (mostly in the final section but also some in the first section too).15 The catalogue was therefore probably issued in 1696 or later.

Catalogue A: Livres francois (Halle: Arnaud du Sarrat, c.1696), p.60 (London, British Library, 822.a.45)

Among the miscellaneous French books in the first section of Catalogue A are the following musical items:

p.43:

Opera de Achille, Tragedie en musique 4.

p.46:

Pseaumes de Godeau en musique, 8. 4. parties

Pseaumes en musique 24. Amsterdam.

Pseaumes de Conrard en musique.

Pseaumes de Godeau avec le premier Verset en musique. 12.

p.47:

Recueil de Chansons, & airs d’Operas les plus Nouveaux 12. 6. parties. 1695.

p.48:

Recueil des Opera par Lully, 12. 3. vol.

Prominent here are settings of metrical psalms using French versifications by Antoine Godeau and Valentin Conrart, devotional music likely to appeal to Huguenot refugees. The setting of Godeau’s psalms in four parts is probably the 1691 collection by Jacques de Gouy.16 The items derived from Lully operas are indicative of the wide dissemination of his music in 1690s Europe. While the three-volume ‘Recueil des Opera par Lully’ in duodecimo format presumably contained librettos rather than musical notation, a noteworthy inclusion is the opera Achille et Polyxène, started by Jean-Baptiste Lully shortly before his death and completed by Pascal Collasse; the quarto edition specified here was published in Amsterdam in 1688 by Antoine Pointel.17

In Catalogue A, the section of Libri musici includes the following (see also illus.1):

p.60:

Suonato per il Violino del Signore Schenck, fol. 1693.

Recueil de Trios pour les Instruments, dedie à l’Electeur de Baviere, 4. 3. parties.

p.61:

Pseaumes de Godeau en Musique, 12. 4. parties.

Trio des Opera par l’ully [sic] en Musique, 4 [illegible] vol.

Some of these items would be for occupational musicians or recreational musicians of advanced ability. The ‘Recueil de Trios’ probably denotes the Premier livre de trios des plus célèbres autheurs (Amsterdam, 1692) published by Amédée le Chevalier. The violin sonatas by Schenck may be the Il giardino armonico (Amsterdam, 1692) again published by Amédée le Chevalier, although the surviving printed edition contains trio sonatas for two violins, viola da gamba and continuo, and is dated one year earlier than the date given by du Sarrat. Possibly du Sarrat’s catalogue entry testifies to a now lost collection by Schenck.

Catalogues B and C survive sewn together in a volume preserved in the Franckesche Stiftungen in Halle (shelfmark 186 a 19):

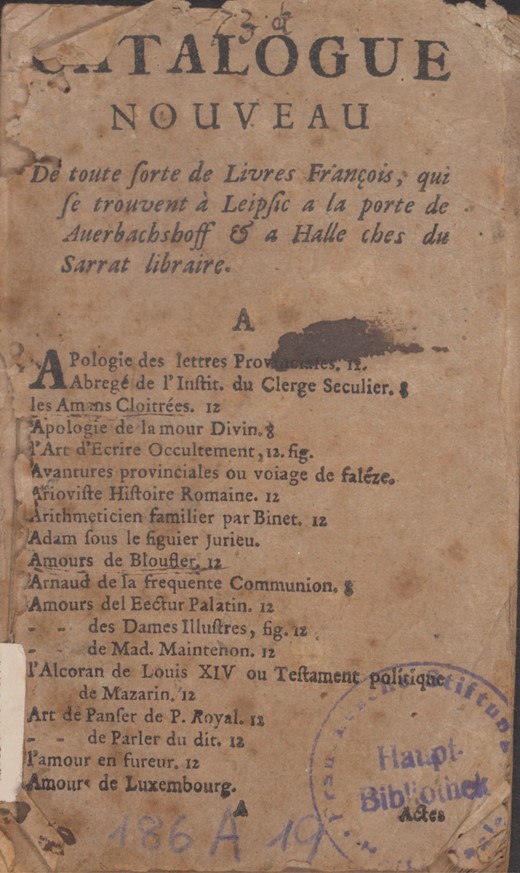

[B:] CATALOGUE NOUVEAU De toute sorte de Livres François, qui se trouvent à Leipsic a la porte de Auerbachshoff & a Halle ches du Sarrat libraire.

A new catalogue of all sorts of French books available in Leipzig at the Auerbachs Hof gate and in Halle, at the bookstore of du Sarrat.

[C:] CATALOGUS LIBRORUM Qui venales prostant Hallensis apud A. DUSARRAT.

A catalogue of books that are sold in Halle by A[rnaud] du Sarrat.

Catalogue B consists of 56 pages listing French works sorted alphabetically with no regard for the varied subject matter (illus.2). Catalogue C is organized in a similar fashion but comprises only 16 pages, listing books in Latin (pp.1–14), Italian (pp.14–15) and Spanish (p.16). Neither catalogue is dated, but Catalogue B lists many items from 1696 and 1697, as well as a few from the year 1698 which can be assumed as the terminus a quo.18 Many books listed in Catalogue C are dated 1696 and one is dated 1697, therefore this catalogue was probably issued around 1697.19

Catalogue B: Catalogue nouveau (Leipzig/Halle: Arnaud du Sarrat, c.1698), title-page (Franckesche Stiftungen zu Halle, 186 a 19)

Catalogues B and C both contain books on a variety of subjects, including some music. Catalogue B repeats the first six musical items listed in Catalogue A (see above), and additionally lists the following:

p.43:

Parodiés Bachiques, 12

p.47:

Recueil des opera par lully [sic] avec les notes 4

p.48:

Recueils [sic] d’Airs serieux & à boire en musique 4. 96

p.53:

Trios des Operas de Lully en Musique in 4. 6. vol. mis en ordre par Amedée le Chevalier.

These items include collections of secular songs aimed at a wide range of audiences, such as the ‘Parodiés Bachiques’20 or the ‘Recueils d’Airs serieux & à boire en musique’.21 The ‘Trios des Operas de Lully’ in six volumes is an edition of 1690–1 by the Amsterdam publisher Amédée le Chevalier.22 The only music in Catalogue C is a reference to the ‘Suonate per il Violino del Signore Schenck, fol.’ (p.15) already encountered in Catalogue A (see above).

Catalogue D, the final surviving catalogue from du Sarrat, is preserved in the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Bibliothek in Hannover (shelfmark bb 565):

LIVRES NOUVEAUX & autres qui se trouvent chéz A. DUSARRAT Marchand Libraire à Halle, & à Leipsig dans le Rothetz Hoff.

New and other books that can be found at A[rnaud] du Sarrat’s, a bookseller in Halle and Leipzig at Rothetz Hof.

The catalogue consists of three sections: Livres nouveaux (pp.1–25), Libri Latini (pp.26–32) and Libri Italiani (pp.33–4). Section one features mostly French works (and a couple of German and Dutch ones), published mainly in Paris and Amsterdam, on subjects ranging from theology, architecture, rhetoric and fiction to fruit-tree cultivation. The catalogue lists periodicals issued in 1701,23 hence its date is probably around 1701. Du Sarrat moved to Berlin in late 1702,24 which is the likely terminus ante quem for all his catalogues discussed here. Like Catalogue B, the title-page of Catalogue D indicates du Sarrat sold books not only in Halle but also in Leipzig, one of Europe’s leading centres for the book trade via its prestigious book fairs.

The first section of Catalogue D lists several musical items:

p.14:

Pseaumes grosse lettre tout musique. 12.

p.16

Neue Testament mit Lobwasser Musique nompareille.25 12. Amsterd.

—Idem mit Lobwasser erste Vers Musique. 12.

—Idem mit Loca Parall. und Lobwasser tout Musique. 12.

Lobwasser Colonel erste Vers Musique mit Prosa. Amsterdam.

—Idem mit rote Linien. 24.

p.20:

Recueil des Airs nouveaux, &c. 12.

Here, along with another anthology of airs, du Sarrat included various bibles with settings of the metrical psalms in the translation by Ambrosius Lobwasser, set to the Genevan tunes. Possibly these psalters printed in Amsterdam were intended for a German Lutheran market.

Du Sarrat and foreign booksellers

Du Sarrat had close connections with French and Dutch booksellers. As an advertisement in Catalogue D explains:

From Mr du Sarrat’s in Halle, every month without fail, one can purchase all the newest publications released in the Netherlands and in France.26

That du Sarrat visited the Netherlands in person and was also active within Pietist correspondence networks is corroborated by a handwritten copy book in the Franckesche Stiftungen collections in Halle. This contains a meticulous copy of a letter sent to du Sarrat on 10 July 1698 by Theophilus Dorrington in the Hague. Dorrington (1654–1715) was an English clergyman who acted as an intermediary between Halle Pietists and English Puritans, following contact established by Heinrich Wilhelm Ludolf (1655–1712).27

Letter from Mr Theophilus Dorrington to Mr Du Sarrat, dated in The Hague, July 10, 1698. Sir, It always gives me great pleasure to receive writings by Mr Francke, a person for whom I have great veneration and esteem. I therefore thank you with all my heart for your care of these things that you sent me from him: I would like to serve you in any way that would be in my power. In order to demonstrate it now as well as I can, I give here the names of some important books newly printed in England and which, if you can find them in Amsterdam, would be very worthy to be brought with you to Germany.28

In the rest of the letter, Dorrington asks du Sarrat to pass a letter to August Hermann Francke, and recommends various religious books in English and Latin, for instance on the subject of Socinianism. The letter shows that du Sarrat was active in circulating religious texts in Pietist networks, and also implies that du Sarrat had a trip planned to Amsterdam to obtain books there.

Du Sarrat’s collaboration with foreign publishing houses (whether direct or indirect) is corroborated by the musical items in his catalogues. Many of them were published by the Amsterdam firms of Antoine Pointel and Amédée le Chevalier. Pointel was active in Amsterdam only from 1685, and went on to sell his stock to le Chevalier in 1692.29 Le Chevalier’s publications in turn were printed by Pieter and Joan Bleau. According to Rudolf Rasch, the Bleau brothers auctioned off their tools of trade in 1695,30 around the time du Sarrat began his operation in Halle and at least a year before Catalogue A was issued. Many of the Bleau brothers’ printing implements were most likely bought by Estienne Roger.31

It is possible that du Sarrat was already selling music published or retailed by Roger during his time in Halle. In 1696 Roger advertised his stock as including not only his own printed music but also works issued by other publishing houses, or their handwritten copies:

It is hereby announced to the public, especially booksellers from foreign lands who would like [to purchase] these music books... that it will suffice them to write a letter to the booksellers Estienne Roger or J[ean] L[ouis] de Lorme in Amsterdam... those wishing [to purchase] any music printed in France or Italy, or handwritten copies, are asked to address those same booksellers, who offer a wide variety [of music] at reasonable prices....32

Indeed, Roger’s catalogues published between 1698 and 1708 feature a section with ‘foreign’ prints (i.e. issued by other publishing houses), including almost all the music published by Johan Philips Heus, Antoine Pointel and Amédée le Chevalier.33 Hence du Sarrat may have obtained the printed music in his catalogues from Estienne Roger, or alternatively directly from le Chevalier (who was based in Ghent from 1698),34 or indirectly via other Amsterdam booksellers such as Jean-Louis de Lorme35 or Pierre Mortier I (1661‒1711).36

Insights into the international trade in music at the end of the 17th century can be found in a letter from Lotharius Zumbach von Koesfeld in Leiden to Sir John Clerk of Penicuik in Rome, dated 23 May 1698:

I lament that I will not be able to render my service to you or to Mr Corelli by selling copies of his Opus 5. For there is a music printer in Holland that is the bane of all composers (both Italian and local ones). He is called Estienne Roger and lives in Amsterdam, and he started to thrive from the time you left. This man, then, takes care to have all the music sent to him from Italy and Germany as quick as possible and still wet from the press by post, and reprints it so quickly that before any copies can arrive here from Italy he just sells his own copies in the whole of Holland37 and Germany. …

I have heard what not long ago happened to Mr Torelli, the very famous violinist, who stayed in Holland during the previous winter. This Mr Torelli, while he was still in Germany and was moving from there to Holland, left his Opus 6 (if I am not mistaken) at a music printing house in Augsburg, in order to be printed there, with an arranged number of copies to be donated to him and sent off to Holland. When Roger from Amsterdam got to know this, he took care to get as quick as possible a copy of this Opus 6 by post from Augsburg, and within a few weeks he reprinted and sold his copies in the whole of Holland and the rest of the Low Countries38 and even in Germany, before those copies sent from Germany to Mr Torelli (which were being slowly conveyed with some other stuff) could arrive in Holland; and this caused great harm and annoyance to Mr Torelli, who was by then in Amsterdam. And he did the same with other composers.39

Even acknowledging the anecdotal character of this story, it seems surprising that Roger would have been sufficiently familiar with the German market in order to distribute his publications there about ten years prior to the first documented evidence of his agents operating in German-speaking lands. Perhaps Du Sarrat could have been an agent for Roger at this early date. Both were Frenchmen by birth, and Roger used the international network of Huguenot merchants efficiently and to great effect.40 Nevertheless it must be remembered that du Sarrat could have obtained his musical wares from other sellers, so his connection with Roger in the 1690s remains hypothetical.

Conclusions

The analysis of archival documents and extant catalogues of Arnaud du Sarrat has shown that he was a Frenchman (and probably a Huguenot) active in Halle from 1694/5 until 1702 as a bookseller, bookbinder and publisher, and also had his business represented in Leipzig from at least 1698 until 1702. Among his wares, he distributed printed music from Amsterdam firms such as Antoine Pointel and Amédée le Chevalier, and had ongoing trade relationships with Amsterdam booksellers.

The total number of music books in du Sarrat’s catalogues is relatively low. Even so, since he advertised that the most recent French and Dutch publications could be purchased from his bookstore, it is not far-fetched to imagine that upon a customer’s request he would have been able to order in any item of printed or manuscript music available in Amsterdam, including music by Corelli, Albinoni and Torelli among others. Perhaps this could have been a route whereby the Halle organist Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow built up his ‘large collection of Italian as well as German music’ (as described by Handel’s biographer John Mainwaring).41 Perhaps, too, the young Handel could have used du Sarrat’s connections to obtain music from Amsterdam such as Roger’s 1701 edition of Tomaso Albinoni’s Sinfonie e concerti a cinque op.2.42 More widely, du Sarrat’s extensive import of French books would have been useful to polyglots such as the Leipzig organist Johann Kuhnau, who showed his awareness of popular literature in his three published novels.43

Du Sarrat’s activities thus show the role of booksellers in the dissemination of music from France and the Low Countries in central German lands around 1700. The evidence uncovered in this article shows the numerous interlocking networks that could potentially bring music and other cultural goods to Halle and Leipzig, including the correspondence networks of Pietists in Halle. Further work in this area may uncover more detailed evidence of the activity of agents of Estienne Roger.44 In broader terms, the many bookstores in early modern towns and cities can be seen as potentially important places for the dissemination of music. The catalogues of these booksellers provide unique insights into the music market, showing the composers and genres available in a location, and also suggesting the richness and diversity of the local musical culture.

Translated by Zofia Wąchocka.

Tomasz Górny is a reader in the Institute of Musicology at the University of Warsaw. He studied literature at the Universities of Kraków, Toulouse and Düsseldorf, as well as organ music at the Conservatory of Amsterdam (with Jacques van Oortmerssen and Pieter van Dijk). His recent research explores the international trade in music books in the long 18th century and Johann Sebastian Bach’s instrumental compositions (especially the keyboard works).[email protected]

I am grateful for the assistance of scholars at the Bach-Archiv, Leipzig, notably Christine Blanken for her comments on my research findings and her stimulating discussions over a cup of tea. The comments of editor Stephen Rose and the anonymous readers for this journal were extremely helpful and enabled me to eliminate many inaccuracies and inconsistencies. Finally, my thanks go to the librarians of the Franckesche Stiftungen in Halle, especially Laura Herrmann and Dirk Glettner. Writing this article was possible thanks to financial support from the University of Warsaw.

Footnotes

I. H. van Eeghen, De Amsterdamse boekhandel 1680–1725, Part I: Jean Louis de Lorme en zijn copieboek (Amsterdam, [1960]), p.115; D. L. Paisey, Deutsche Buchdrucker, Buchhändler und Verleger 1701–1750 (Wiesbaden, 1988), p.48; C. Berkvens-Stevelinck, ‘Französische Bücher und Buchhändler in Berlin’, in Franzosen in Berlin. Über Religion und Aufklärung in Preußen. Studien zum Nachlass des Akademiesekretärs Samuel Formey, ed. M. Fontius and J. Häseler (Berlin, 2019), pp.253–92, at pp.254–5.

For extensive information about Roger’s activity, see Rudolf Rasch’s website The music publishing house of Estienne Roger, https://roger.sites.uu.nl/. See also F. Lesure, Bibliographie des éditions musicales publiées par Estienne Roger et Michel-Charles le Cène (Amsterdam, 1696–1743) (Paris, 1969); R. Rasch, ‘Estienne Roger’s foreign composers’, in Musicians’ mobilities and music migrations in early modern Europe. Biographical patterns and cultural exchanges, ed. G. zur Nieden and B. Over (Bielefeld, 2016), pp.295–309. For one of the first scholarly references to du Sarrat as agent of Roger, see K. Hortschansky, ‘Die Datierung der frühen Musikdrucke Etienne Rogers. Ergänzungen und Berichtigungen’, Tijdschrift van de Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis, iv (1972), pp.252–86, at p.271.

‘On avertit tous les Amateurs de Musique qu’on en trouve un assortiment général à Amsterdam, Chez Estienne Roger … On trouve aussi les dits livres à Londres, Chez François & Paul Vaillant Marchands Libraires, & à Berlin chez A. Du Sarrat.’ Pierre de la Roque, Recueil de diverses dernieres heures edifiantes (Amsterdam: Estienne Roger, 1706), p.[239]. Copy consulted: Franckesche Stiftungen, Halle, 1 h 28.

Estienne Roger, Catalogue des livres de musique (Amsterdam: Estienne Roger, [1708]), p.1. Copy consulted: R. Rasch, The music publishing house of Estienne Roger: Catalogues Roger 1708‒1716: https://roger.sites.uu.nl/wp-content/uploads/sites/416/2019/09/Catalogues-Roger-1708-1716.pdf. Estienne Roger, Catalogue de la musique (Amsterdam: Estienne Roger, [1712]), p.1; copy consulted: Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, M: Be Sammelmappe 1 [28]. Estienne Roger, ‘Catalogue de musique’, in [Denis Vairasse], Histoire des Sevarambes (Amsterdam: Estienne Roger, 1716), pp.291–348, at p.291. Copy consulted: https://archive.org/details/histoiredessevar00vair/page/n5.

Jacques Esprit, La fausseté des vertus humaines (Amsterdam: Estienne Roger, 1709), last two unnumbered pages. Copy consulted: Amsterdam University Library, bj 1520.e7 1717 [LCC]. Mathurin Régnier, Les Oeuvres (Amsterdam: Estienne Roger, 1710), last two unnumbered pages. Copy consulted: Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, M: Lm 3009.

‘Demnach bey Sr: Churfürstl:[ichen] Durchl:[aucht] zu Brandenburg Unserm gnädigsten Herrn, der französische Buch Händler und Buch Binder Arnaud du Sarrat, beglaubte Attestata produciret, daß er so theur Professionen erlernet, und da benebst unterthändigst gebeten, weil er entschloßen sich von hinnen nach Halle zu begeben und daselbst zu etabliren, Höchstgedachte Sr: Churfürstl:[iche] Durchl.[aucht] wolten ihm die Gnade thun, und bey der neuen Universitæt daselbst zum Buchführer und Buchbinder zu bestellen …’ Archiv der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Rep. 27 Theologische Fakultät, Nr. 1286—Landesherrliche Edikte—1688–94: document no.66 (Buchhändler und -binder Arnaud de Sarrat, 1694). Transcription by Christine Blanken of the Bach-Archiv, Leipzig.

Archiv der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Rep. 27 Theologische Fakultät, Nr. 1286—Landesherrliche Edikte—1688–94: document no.72 (Konzession des Buchhändlers Arnaud de Sarrat, 1694).

J. Häseler, ‘Religion und Aufklärung in Preußen: der Beitrag der Hugenotten’, in Franzosen in Berlin, pp.39–96.

B. Baselt, ‘Handel and his central German background’, in Handel. Tercentenary collection, ed. S. Sadie and A. Hicks (London, 1987), pp.43–60, at pp.45–6.

Catalogue A. British Library, 822.a.45.

Livres qui se trouvent à Cologne, chez PIERRE MARTEAU, Catalogue A, p.[62].

K. K. Walther, Die deutschsprachige Verlagsproduktion von Pierre Marteau/Peter Hammer, Köln. Zur Geschichte eines fingierten Impressums (Leipzig, 1983).

Catalogue A, pp.[65–6].

‘On trouve chez ledit Arnaud du Sarrat Outre les livres specifies dans ce Catalogue, toutes sortes de bons Livres Allemands, & Latin, & autres bons livres vieux’ (Many other books named in this catalogue can be found at Arnaud du Sarrat’s, as well as all sorts of good books in German and Latin, and assorted good older books). Catalogue A, p.[67].

For example, ‘Don Quichotte de la Manche, traduit par Arnaud Dandilly 12. 5. Vol. fig. 1696.’, Catalogue A, p.15; ‘Secretaire des Amans […] 12. nouv. Edit. 1696.’, Catalogue A, p.50.

Jacques de Gouy, Airs à quatre parties sur la Paraphrase des pseaumes de Godeau (Amsterdam: [Amédée le Chevalier], printed by Pieter and Joan Bleau, 1691).

Jean-Baptiste Lully, Pascal Collasse, Achille et Polyxène (Amsterdam: Antoine Pointel, 1688). A folio edition had also been published by Ballard in Paris in 1687. See M. Shichijo, ‘Les suites instrumentales issues des opéras de Lully publiées à Amsterdam: études historique, philologique et musicale sur l’éditeur Estienne Roger (1665/66–1722)’ (PhD diss., Université Paris-Sorbonne/ Aichi University of the Arts, 2017), p.62.

‘Recueil de plusiers pieces curieuses tant en prose qu’en vers 12. plusieurs parties 1698.’ Catalogue B, p.46.

‘Veneroni Grammatica Italiano Francesse 1697.’ Catalogue C, p.14.

This is probably Parodies bachiques, sur les airs et symphonies des Opera. Recueillies & mises en ordre par Monsieur Ribon (Paris: Christophe Ballard, 1696). The work was available in Estienne Roger’s Amsterdam bookstore since at least 1699. See R. Rasch, ‘The music shop of Estienne Roger (1698–1708)’, in ‘La la la … Maistre Henri’. Mélanges de musicologie offerts à Henri Vanhulst, ed. C. Ballman and V. Dufour (Turnhout, 2009), pp.297–314, at p.307.

Collections of this kind were popular at the turn of the 18th century. They were published monthly by Christophe Ballard’s Paris publishing house and reprinted by Estienne Roger in Amsterdam. See J.-P. Goujon, ‘Les “Recueils d’airs sérieux et à boire” des Ballard (1695–1724)’, Revue de Musicologie, xcvi/1 (2010), pp.35–72.

This may be the same publication as listed in Catalogue A, p.61. Jean-Baptiste Lully, Les trios des opéra (Amsterdam: [Amedée le Chevallier], printed by Pieter and Joan Blaeu, 1690), [part 1]; Jean-Baptiste Lully, Les trios des opéra (Amsterdam: [Amedée le Chavellier], printed by Pieter and Joan Blaeu, 1691), [part 2]. On this publication, see Shichijo, ‘Les suites instrumentales issues des opéras de Lully’, pp.63–4, 86–7.

For example on page 3: ‘Mercure historique continué, 1701’; ‘Lettres historiques continué, 1701’.

van Eeghen, De Amsterdamse boekhandel 1680–1725, Part I: Jean Louis de Lorme en zijn copieboek, p.115.

Probably ‘non pareille’ (‘not the same’).

‘On trouve chez le Sr. DUSARRAT à Halle tous les mois regulierement, tout ce qu’il y a de nouveau, tant en Hollande qu’en France.’ Catalogue D, p.34.

J. van de Kamp, ‘Das Vorfeld der England-Halle-Kontakte. Theologische und religiöse Austauschprozesse zwischen England und Deutschland im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert’, in London und das Hallesche Waisenhaus. Eine Kommunikationsgeschichte im 18. Jahrhundert, ed. H. Zaunstöck, A. Gestrich and T. Müller-Bahlke (Halle, 2014), pp.49–63, at p.61; A. Schunka, ‘“An England ist uns viel gelegen.” Heinrich Wilhelm Ludolf (1655–1712) als Wanderer zwischen den Welten’, in London und das Hallesche Waisenhaus, pp.65–86, at p.82.

‘Lettre de mr. Theophilus Dorrington a Monsr. Du Sarrat, datée à la Haye, Juillet 10, 1698. Monsieur, Il me donne tousjours un grand plaisir à recevoir des escrits de Mr. Franck, une Personne pour laquelle j’ay une fort grand veneration et estime. Je vous remercie donc de tout mon coeur pour vôtre soin de ces choses que Vous m’avez envoyez de luy: Je voudrois vous servir en toutes manieres qui seroient dans mon pouvoir. Afin que je le montre à present si bien que je le puis faire, je donne icy les noms de quelques Livres d’importance nouvellement imprimées en Angleterre; lesquels si vous les pouvez trouver à Amsterdam, ils seroient fort dignes d’etre apportées avec vous à Allemagne …’ Franckesche Stiftungen, Halle, afst/h d 93, p.61. English translation by Patrycja Czarnecka-Jaskóła.

Rasch, ‘The music shop of Estienne Roger’, p.300.

R. Rasch, ‘Publishers and publishers’, in Music publishing in Europe 1600–1900. Concepts and issues, bibliography, ed. R. Rasch (Berlin, 2005), pp.183–208, at p.196.

Rasch, ‘Publishers and publishers’, p.196.

‘On avertit le public & particulierement les Libraires des Pays Etrangers, que s’ils souhaittent de ces livres de Musique …, ils n’ont qu’à escrire à Estienne Roger ou à J. L. de Lorme Libraires à Amsterdam … ceux qui souhaitteront quelque Musique que ce soit, imprimée en France ou en Italie où Copiée à la main, ils n’ont qu’à s’adresser aux mêmes libraires chés qui l’on en trouve de toutes les sortes à un prix raisonnable. …’ Catalogue appended to Recueil d’airs sérieux et à boire, livre second (Amsterdam: Jean-Louis de Lorme, Estienne Roger, 1696). Copy consulted: R. Rasch, The music publishing house of Estienne Roger: Catalogues Roger 1696–1700, p.2: https://roger.sites.uu.nl/wp-content/uploads/sites/416/2019/09/Catalogues-Roger-1696-1700.pdf.

Rasch, ‘Publishers and publishers’, p.195, Rasch, ‘The music shop of Estienne Roger’, p.300.

H. Vanhulst, ‘Le Chevalier, Amédée’, in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. S. Sadie (London, 2001), xiv, p.440.

Copies of letters sent by de Lorme to du Sarrat in 1707 are preserved in the Amsterdam City Archive (201: Archief van de Waalsch Hervormde Gemeente: 2180 b). See van Eeghen, De Amsterdamse boekhandel 1680–1725, Part I: Jean Louis de Lorme en zijn copieboek, p.115.

Mortier is well known for his competition with Roger in the years 1707–11 (see F. Lesure, ‘Estienne Roger et Pierre Mortier: Un épisode de la guerre des contrefaçons à Amsterdam’, Revue de Musicologie, xxxviii (1956), pp.35–48; Rasch, ‘Publishers and publishers’, pp.197–9), but he was already active in Amsterdam as a music seller in the 1690s.

In the original Latin ‘Belgium’ (see below).

In the original Latin ‘Belgium’ (see below).

‘Doleo interea quod vel tibi vel Domino Corelli illud servitium præstare nequeam ad vendendum exemplaria Operæ eius quintæ. Unus enim est in Hollandia Typographus Musicus in ruinam omnium componistarum tam Italorum quam hujatium. Vocatur ipse Stephanus Roger, habitans Ambstelodami, qui florere incepit ab eo tempore quo tu hinc discessisti. Hic ergo omnem musicam ex Italiâ et Germaniâ quam habere potest et adhuc ferè prælo madidam per postam quantocijus sibi transmitti curat et reimprimit tam citò ut antequam ulla exemplaria ex Italiâ advenire possint, tunc ille sua modo per totum Belgium et Germaniam vendidit. … Audi quid hic nuper acciderit Domino Torelli Violista celeberrimo qui per hijemem antecedentem hic in Hollandia moratus fuit. Hic Dominus Torelli dum adhuc in Germaniâ |b| fuisset et indè ad Hollandiam discessisset, reliquit ibi Augspurgi apud Typographum Musicum Opus suum (ni fallor) sextum, ut ibidem imprimeretur, certâ initâ conditione cum Typographo pro numero exemplarium sibi donandorum et in Hollandiam transmittendorum. Quod cum percepisset ille Roger Ambstelodamensis quantocijus per postam transmitti sibi curavit unum exemplar istuis Operae 6tae Auspurgo, et intra paucas septimanas reimpressit et exemplaria sua vendidit per totam Hollandiam et reliquum Belgium, imò etiam Germaniam antequam illa exemplaria pro Domino Torelli ex Germaniâ transmissa (quae tardè cum mercibus quibusdam advehebantur) in Hollandiam advenire potuissent et hoc in maximum damnum et fastidium Domini Torelli qui tunc Ambstelodami præsens erat. Eodem modo ille facit cum aliis componistis.’ Edinburgh, National Archives of Scotland, Penicuik Papers (gd18/5202/24). English translation (by Andrew Woolley and Rudolf Rasch) and the transcript of the original source quoted from: R. Rasch, The music publishing house of Estienne Roger: documents 1698, pp.13–15. https://roger.sites.uu.nl/wp-content/uploads/sites/416/2018/07/Documents-1698.pdf. As noted by Rasch, the edition mentioned here is likely Torelli’s Concerti musicali, op.6, printed in Augsburg by the heirs of Lorenz Kroniger, Theophil Göbels and Johann Christoph Wagner in 1698.

Shichijo, ‘Les suites instrumentales issues des opéras de Lully’, pp.11–14, 21–4.

J. Mainwaring, Memoirs of the Life of the Late George Frederic Handel (London: Dodsley 1760), p.14.

If Handel became acquainted with ritornello form during his time in Halle, the dating of his early compositions might have to be reevaluated, such as the Oboe Concerto in G minor, hwv287. See H. J. Marx, ‘Zur Echtheit des Oboenkonzertes hwv287 von Georg Friedrich Händel’, in Beiträge zur Geschichte des Konzerts. Festschrift Siegfried Kross zum 60. Geburtstag, ed. R. Means and M. Wendt (Bonn, 1990), pp.33–40, at p.39; S. Rampe, ‘Die Solokonzerte für Oboe sowie Violine’, in Das Händel-Handbuch, ed. H. J. Marx, Band 5: Händels Instrumentalmusik, ed. S. Rampe (Laaber, 2009), pp.382–91, at p.385.

On Kuhnau’s novels, see S. Rose, The musician in literature in the age of Bach (Cambridge, 2011), pp.125–50.

See T. Górny, ‘Estienne Roger and his agent Adam Christoph Sellius: new light on Italian and French music in Bach’s world’, Early Music, xlvii (2019), pp.361–70.