-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Karolina Baranowska, Learning most with least effort: subtitles and cognitive load, ELT Journal, Volume 74, Issue 2, April 2020, Pages 105–115, https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccz060

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The article reports a study investigating the effects of different subtitling conditions on cognitive load, incidental vocabulary learning, and comprehension. In the study, 63 Polish intermediate learners of English were asked to watch a movie clip and subsequently to answer comprehension questions, take a vocabulary knowledge test, and fill in a self-reported cognitive load questionnaire. They were divided into three groups: one group watched the clip with Polish subtitles, one with English subtitles, and one without subtitles. The findings indicate that intralingual (L2) subtitles assist learners in vocabulary acquisition more than interlingual (L1) subtitles. Moreover, both types of subtitles lower cognitive load, which is accompanied by greater comprehension of the material presented. The results of the study offer some practical implications for EFL teachers and learners.

Learning English through the media

In the past few decades, foreign language films and online media have received considerable attention in the ELT literature. Previous research reveals that exposure to various media positively correlates with foreign language acquisition in the case of both younger and older learners. For example, in the Early Language Learning in Europe project (Enever 2011), researchers explored, inter alia, the impact of out-of-school exposure to English in the case of primary school children from a range of European countries. As it turned out, the amount of exposure to foreign language films outside the classroom correlated positively with learners’ test scores in listening and reading comprehension. Thus, the researchers suggest that undubbed television programmes should be more available to children since ‘the benefits of this additional language exposure outweigh the effort required’(Enever 2011: 7). There is also evidence that secondary school learners enhance their foreign language proficiency by means of watching videos in the target language. The aim of another large-scale study, First European Survey on Language Competences, was to collect data on foreign language learners’ proficiency in different European countries. Secondary school students from 16 educational systems were tested on their listening, reading, and writing skills in the two most widely taught foreign languages in their educational systems. Overall, the results revealed that learners benefited from exposure to the media as evidenced by test scores (Jones et al. 2012).

Even though it is widely believed that children have more capacity for incidental vocabulary learning than adults (e.g. Macnamara 1973), there is ample experimental research which shows that adults can also acquire the target language implicitly. For example, Harji et al. (2010) investigated the benefits of watching English videos by Iranian university students. The participants watched instructional videos either without subtitles or with English subtitles. Among other things, the researchers found that exposure to the media was effective in terms of vocabulary acquisition.

Finally, studies investigating learners’ perceptions of the usefulness of exposure to foreign language media show that such exposure is generally appreciated by learners and believed to be useful for foreign language learning. A recent survey concerning the use of new technologies in learning English conducted by Trinder (2017) revealed that students regarded films and the media as useful tools for developing listening skills, pronunciation, and speaking. Television series or video clips were also perceived as useful for developing communicative competence.

Impact of different subtitling conditions

Watching subtitled films is generally found to be advantageous in terms of overall language improvement, including incidental and intentional vocabulary learning. Vanderplank (1988) noticed that one advantage of subtitles is the fact that they help learners notice unfamiliar language, which is otherwise lost in the speech stream. As Vanderplank (ibid.: 272–73) noted, ‘subtitles might have a potential value in helping the learning acquisition process by providing learners with the key to massive quantities of authentic and comprehensible language input’. English language learners who took part in his study found English language subtitles to be facilitative in terms of comprehension of the presented video material as well as in noticing new words. Aydin Yildiz (2017) examined the impact of watching subtitled videos on comprehension and vocabulary learning in the case of Turkish intermediate students of English. The participants were divided into two groups: one watched movie clips with and the other without English subtitles. After four treatment sessions during which they watched different clips, the participants completed a multiple choice vocabulary test and answered comprehension questions. The results reveal that the group watching subtitled videos outperformed the group watching the videos without subtitles on the vocabulary post-test.

Even though the benefits of watching subtitled foreign language films have been acknowledged by numerous researchers, what still remains to be established is how the video material should be presented to learners, i.e. which subtitling condition assists learners the most in acquiring the target language. Some argue that intralingual subtitles (foreign language subtitles) are more advantageous since they help viewers to recognize the words that are being spoken. For example, Frumuselu et al. (2015) found that intralingual subtitles were more beneficial irrespective of the learners’ language level. The researchers explain that this may be attributable to the fact that intralingual subtitles increase learners’ interaction with the target language. Moreover, intralingual subtitles allow learners to see the written form of the spoken word, which makes them more confident. However, interlingual subtitles (native-language subtitles) have also been found to contribute to vocabulary acquisition. Koolstra and Beentjes (1999) investigated incidental vocabulary learning in the Dutch context. They exposed one group of children to an English programme with Dutch subtitles, one group to a version without subtitles and one group to a Dutch programme as a control condition. Their findings show that the presence of standard subtitling (L1 subtitles) can contribute to incidental learning of vocabulary.

Although in most studies subtitles were found to be useful in foreign language acquisition, there are also studies which show that watching subtitled videos did not lead to greater vocabulary acquisition than watching videos without subtitles. To take one example, Karakas and Sariçoban (2012) investigated the impact of subtitled cartoons on incidental vocabulary learning. They found that the group that watched an experimental video with English subtitles did not have more vocabulary gains than the group that watched the version without subtitles. However, both groups improved their scores from the pre-test to the post-test, which means that mere exposure to videos can assist in vocabulary acquisition.

Learning and cognitive load

Cognitive load can be defined as ‘a multidimensional construct representing the load that performing a particular task imposes on the learner’s cognitive system’ (Paas et al. 2003: 64). Since there are different sources of cognitive load, it can be subcategorized into intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load. Intrinsic cognitive load is generated by the inherent complexity of the presented material, extraneous cognitive load is generated by the format of the presentation of the information (Brunken et al. 2003), and germane cognitive load ‘constitutes the remaining available cognitive resources’ (Kruger et al. 2014: 3).

In the light of cognitive load theory, subtitles may be regarded as deleterious to learning since viewers have to manage attention distribution between different sources of information, which in turn increases extraneous cognitive load. At the same time, germane cognitive load decreases, which means that there are fewer cognitive resources available for processing and forming schemata (e.g. Brunken et al. 2003). In language acquisition studies, however, subtitles are generally believed to lower extraneous cognitive load by providing visual support, which in turn leads to better performance as well as learning (Paas et al. 2003). Kruger et al. (2014) carried out an experiment on the impact of subtitles and attention distribution on cognitive load and comprehension of an English academic lecture by speakers of English as a second language whose L1 was Sesotho. To measure the level of cognitive load, they used objective measures, i.e. electroencephalography and eye-tracking, as well as subjective measures, i.e. self-reported questionnaires. Interestingly, on the basis of self-reports, they found that the lowest comprehension effort was reported by the group exposed to interlingual subtitles, whereas the highest mental load was experienced by the group exposed to intralingual subtitles.

Although there is now substantial research showing that viewing foreign language films contributes to the development of foreign language proficiency, there is no consensus on the effects of native versus foreign language subtitles on the level of cognitive load experienced by learners and on the amount of vocabulary learning and comprehension that takes place. Moreover, little is known about the interaction of cognitive load, vocabulary learning, and comprehension during exposure to videos in different subtitling conditions. On the basis of previous research in the field (e.g. Kruger et al. 2014), it can be hypothesized that subtitles in general will not result in cognitive overload and will even lower the level of cognitive load, although it is difficult to predict whether interlingual or intralingual subtitles will induce lower cognitive load. Determining how cognitive load influences learning is important in foreign language education since it allows for the appropriate choice of learning materials that make students learn the most at a minimal cost. It may be expected that lower cognitive load results in greater vocabulary acquisition and comprehension of the video material presented. Learning materials that generate low cognitive load are likely to boost interest in learning foreign languages since learning will not be perceived as a tedious activity, but rather a pleasant and effortless process. In order to address the above-mentioned issues, the following research questions have been formulated:

1) What are the effects of different subtitling conditions on the level of cognitive load experienced by learners while viewing English language videos?

2) What are the effects of different subtitling conditions on the level of comprehension of English language videos?

3) What are the effects of different subtitling conditions on the acquisition of English vocabulary?

4) Is there a relationship between the level of cognitive load experienced by learners while viewing videos and vocabulary acquisition?

5) Is there a relationship between the level of cognitive load experienced by learners while viewing videos and comprehension?

The study

Method

Participants and procedure

The participants of the study were 63 Polish learners of English selected by means of convenience sampling from a high school in Słupca, Greater Poland Voivodship. They were at an intermediate level of proficiency (B1), which was determined on the basis of the coursebook they were using at the time of the study and the teacher’s report. Three intact groups were used: there were 20 students in the first group, 22 in the second, and 21 in the third group. The participants were informed about the general aims of the study; they were asked to watch the movie carefully and were also told that they would be asked questions about it afterwards. First, each group completed a pre-test on vocabulary items from the movie. Subsequently, the first group watched the video material without subtitles, the second group with Polish subtitles, and the third group with English subtitles. After the viewing, the participants completed a post-test on comprehension and vocabulary, as well as a self-reported questionnaire concerning cognitive load.

Materials

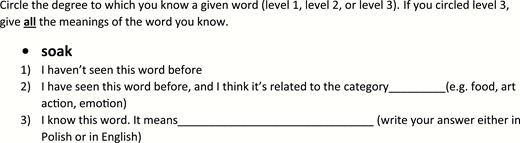

The materials used in the study included a pre-test which consisted of two parts. The first part contained questions checking the participants’ familiarity with the video clip to be presented, so as to eliminate students who were familiar with the television series, as the likelihood of them knowing the experimental clip would then be too high. The second part was a Revised Vocabulary Knowledge Scale (RVKS) test, adapted from Zhao and Macaro (2016: 86). Figure 1 is an example item from the test along with the instructions that were provided.

As Figure 1 shows, the test consists of a three-point scale concerning vocabulary knowledge: ‘I haven’t seen this word before’, ‘I have seen this word before, and I think it’s related to the category__’, ‘I know this word. It means (answer in Polish or English)’. The first level is worth 0 points, the second 1 point, and the third one is worth 2 points. In total, there were 30 words, 10 of which were fillers to distract the participants from the purpose of the study. Although the participants were asked to give all the meanings of a given word they knew, they got a point only if they knew the meaning in which the word was used in the video clip. Therefore, what was measured was the ability to infer context-dependent meanings (ad hoc concepts)—a student obtained a point in the post-test only if the meaning given was the required meaning, and this required meaning was the meaning that had to be inferred from the context.

The video material was a 12-minute clip from the first episode of the television series Gilmore Girls. The rationale behind choosing this particular series was that it was highly likely that the series was not well-known by teenagers as it ended its run in 2007, yet it is authentic material so does not pose a threat to the external validity of the study. Moreover, the scenes include mostly dialogues, so the participants were not able to answer comprehension questions without comprehending the language used in the video material.

The post-test consisted of two parts. In the first one, the participants were asked to answer eight comprehension questions. Seven of them were worth 1 point, and one was worth 3 points. All the questions were in the participants’ native language. The second part was the RVKS test containing 20 vocabulary items from the video clip. This time the participants were specifically asked to provide the meaning of the words in which they were used in the clip.

A self-reported questionnaire was compiled from the self-report used by Kruger et al. (2014) and NASA Task Load Index (Hart 1986). In total, there were five questions with the answers presented on a five-point Likert scale. Each question was related to one aspect of cognitive load: mental demand, temporal demand, effort, frustration, and engagement.

Results

The effects of subtitles on cognitive load

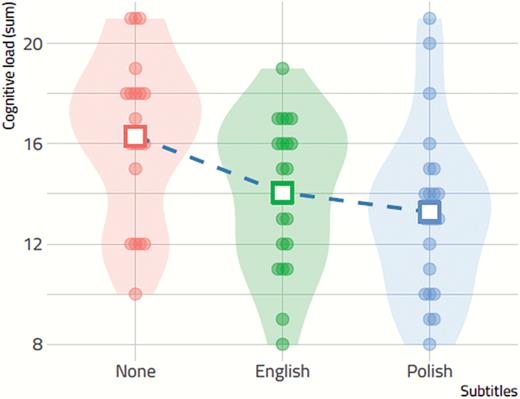

Figure 2 illustrates the level of cognitive load experienced by each participant in the three experimental groups. It shows that the group which watched the version without subtitles experienced the highest mental effort, while the group that watched the clip with Polish subtitles reported the lowest level of cognitive load.

The level of cognitive load in the three experimental groups. Broken line connects means

A Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to check for statistically significant differences. It yielded a statistically significant difference between the impact of different subtitling conditions on the level of cognitive load (P = 0.012). The results of pairwise comparisons show, however, that the only difference to reach the level of statistical significance is the difference between the Polish-subtitles and the no-subtitles group (P = 0.011).

The effects of subtitles on comprehension

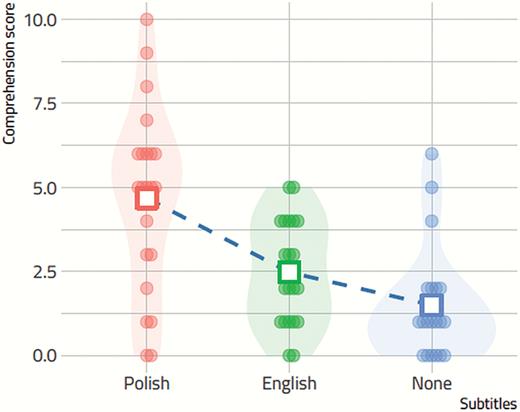

Comprehension questions turned out to be the easiest for the group watching the clip with Polish subtitles, and the most difficult for the group watching the clip without subtitles. As indicated by the Kruskal–Wallis test (P = 0.000), the differences in the level of comprehension between the three groups were statistically significant. Pairwise comparisons demonstrate that statistically significant differences were found between the no-subtitles and the Polish subtitles group (P = 0.000), as well as the English and the Polish subtitles groups (P = 0.038). Figure 3 shows how comprehension decreased from the Polish subtitles, through the English subtitles, to the no-subtitles group. From this, it can be inferred that own-language subtitles facilitate the comprehension of foreign language videos the most.

Comprehension scores broken by groups. Broken lines connects means

The effects of subtitles on vocabulary acquisition

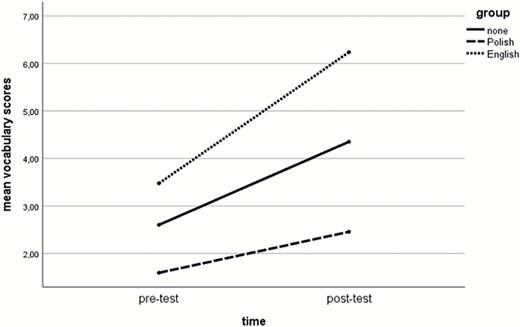

As shown in Figure 4, all experimental groups improved their vocabulary scores from pre-test to post-test.

Mean vocabulary scores on the pre-test and post-test broken by group

Although no statistically significant differences were found between the groups on the pre-test (P = 0.59), the difference between the Polish and the English subtitles groups approached significance (P = 0.07). On the post-test, the differences between the groups proved to be statistically significant (P = 0.003), although the paired comparison analysis showed that the only statistically significant difference was found between the Polish and the English subtitles groups (P = 0.002). Table 1 shows mean vocabulary scores on the pre and post-test, as well as mean vocabulary gains for all three groups. Vocabulary gains were calculated by subtracting the points obtained on the pre-test from the points obtained from the post-test.

Mean scores obtained on the pre-test, post-test, and mean vocabulary gains for all experimental groups

| . | Pre-test . | Post-test . | Vocabulary gains . |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 2.6 | 4.3 | 1.7 |

| Polish | 1.6 | 2.4 | 0.9 |

| English | 3.5 | 6.2 | 2.8 |

| . | Pre-test . | Post-test . | Vocabulary gains . |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 2.6 | 4.3 | 1.7 |

| Polish | 1.6 | 2.4 | 0.9 |

| English | 3.5 | 6.2 | 2.8 |

Mean scores obtained on the pre-test, post-test, and mean vocabulary gains for all experimental groups

| . | Pre-test . | Post-test . | Vocabulary gains . |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 2.6 | 4.3 | 1.7 |

| Polish | 1.6 | 2.4 | 0.9 |

| English | 3.5 | 6.2 | 2.8 |

| . | Pre-test . | Post-test . | Vocabulary gains . |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 2.6 | 4.3 | 1.7 |

| Polish | 1.6 | 2.4 | 0.9 |

| English | 3.5 | 6.2 | 2.8 |

As presented in Table 1, the English subtitles group had the biggest vocabulary gains, while the Polish subtitles group did not acquire many new vocabulary items from the video clip.

The relationship between cognitive load, vocabulary acquisition, and comprehension

In terms of the relationship between the level of cognitive load and vocabulary acquisition, Spearman’s rank-order correlation indicated no statistically significant correlations, either in terms of vocabulary gains for all the groups taken together (rs = –0.047, P = 0.717), or in terms of gains for each group separately.

When it comes to the relationship between the level of cognitive load and comprehension, Spearman’s rank-order correlation showed a statistically significant correlation for all groups taken together (rs = –0.34, P = 0.006). When broken down by groups, a significant correlation was found only in the English subtitles group (rs = –0.596, P = 0.004). Therefore, the results suggest that a high level of cognitive load implies poorer comprehension, at least while watching videos with intralingual subtitles.

Discussion

The current study shows that there is a significant difference between various subtitling conditions when it comes to their impact on cognitive load, comprehension, and vocabulary learning. The results demonstrate that there is a significant difference in the level of cognitive load experienced by learners watching videos in different subtitling conditions. Own-language subtitles contributed to lowering cognitive load more than intralingual subtitles, while the absence of subtitles resulted in the highest level of cognitive load. Cognitive load theory says that a high level of cognitive load may negatively impact learning since it places a greater demand on learners’ mental resources, leaving fewer resources for learning. In the present study, there was a negligible correlation between the level of cognitive load and incidental vocabulary learning in the case of both subtitles groups. Nevertheless, it can be tentatively inferred that materials which generate low cognitive load may be conducive to vocabulary learning as the value of the correlation coefficient was negative, which means that greater cognitive load negatively impacts vocabulary learning.

The current study also set out to determine the impact of cognitive load on comprehension. Since the Polish subtitles group reported the lowest level of cognitive load and at the same time obtained the highest scores on the comprehension post-test, it can be concluded that the higher the level of cognitive load, the more difficult comprehension becomes. Additionally, in line with previous research in the field (e.g. Kruger et al. 2014), subtitles, regardless of their type, were not found to result in cognitive overload, which means that while watching subtitled videos, mental resources are still available for learning.

As regards the differences between subtitling conditions and their impact on incidental vocabulary learning, the results demonstrate that learning foreign language vocabulary through the media can be effective since in all three experimental groups there were some vocabulary gains. It transpired that intralingual subtitles boosted vocabulary acquisition more than interlingual subtitles, which were in turn even less beneficial than the absence of subtitles. It should be noted, however, that the interlingual group had the lowest score not only on the post-test, but also on the pre-test, which could mean that this group was at a lower level of proficiency than the other two groups, hence their vocabulary gains were the smallest. Also, the study set out to investigate incidental vocabulary learning, therefore the participants were not informed about the vocabulary post-test, only about the comprehension questions. Thus, this unexpected finding may also be attributed to the fact that the participants could have focused on comprehension and did not really pay attention to the English words that were spoken, only to Polish subtitles. In contrast, while being exposed to the English language with or without English subtitles, they were probably more concerned with guessing the meaning of the words to understand a given dialogue; with Polish subtitles they did not have to put additional effort to infer the meaning of words as they were translated for them. Accordingly, in terms of comprehension, Polish subtitles turned out to be the most advantageous.

Conclusion

In contemporary classrooms, where learning with the use of new technologies often takes precedence over traditional forms of learning, seeking ways to assist learners in acquiring a foreign language through those technologies should be one of the priorities for educators. In our technologically driven world, access to films and different types of subtitles is no longer a problem, thus teachers can focus solely on the choice of video content relevant to their learners’ current needs.

Videos have an added value of entertainment so that students can learn in a relaxed atmosphere, which lowers the affective filter. They may learn with or without conscious effort (intentional versus incidental learning) and in either case learning is a pleasant activity, which in turn boosts motivation towards learning. Students will use media and watch foreign language films in their free time anyway, so the role of teachers is to make the most of it. The results of the current study as well as previous research in the field show that watching foreign language films, especially with subtitles, is an effective technique of vocabulary learning, and this is why it should become part of mainstream teaching.

The study has important implications for materials developers and teachers promoting out-of-class exposure to videos. There is a need for developing learning materials that include videos. Such videos should be available in different subtitling conditions so that different versions can be used depending on the learning objective—if the focus is vocabulary learning, a movie may be played with intralingual subtitles, if the focus is comprehension (e.g. a film is used as a springboard for discussion), interlingual subtitles may be opted for. Materials designed for ‘flipped classrooms’ will effectively increase the popularity of using videos for language practice. For example, YouTube videos are easily accessed, they are relatively short, usually available with subtitles, and interesting for students, thus materials based on YouTube clips will effectively encourage learners to practise the target language inside and outside the classroom. Nowadays we have access to a variety of technological developments, such as online resources using videos or smart televisions, so teachers should take advantage of these new technologies to make students learn more with less mental effort. The current study showed that it is possible to modify extraneous load related to the learning material—the same film viewed with interlingual and intralingual subtitles may induce a different amount of cognitive load. Thus, educators should help their learners undertake self-learning activities that will not overburden their working memory. Learners should be instructed how to watch foreign language movies at home so as to effectively improve foreign language competency. The current study is therefore useful for teachers inasmuch as it shows which subtitling condition is best suited for intermediate learners when they want to learn new vocabulary items or improve listening comprehension skills.

Due to technological advancement, watching foreign language movies with subtitles is possible even in countries which traditionally preferred dubbing (e.g. France or Spain). Accordingly, the benefits of subtitling for language learners should be widespread so as to encourage students from ‘dubbing countries’ to watch subtitled rather than dubbed movies. The current study offers a promising start for further research into the use of subtitled videos in classrooms and their impact on vocabulary learning, comprehension and cognitive load. The interaction between cognitive load and learning is one of the aspects of the current study that deserves more research. In the study, cognitive load was measured only by means of a subjective measure. It is, however, advisable that further research resort to objective measures of cognitive load, e.g. eye-tracking, as it may provide a better understanding of the actual mental effort experienced. Of particular interest may also be the interaction between different levels of proficiency and the level of cognitive load, vocabulary learning, or comprehension of foreign language videos in different subtitling conditions. While in the present study incidental vocabulary learning was tested, more studies should be carried out on intentional vocabulary learning. When explicitly instructed to pay attention to the language, students can perhaps benefit even more from watching videos during lessons, although possibly with greater cognitive load. Finally, one area that deserves more attention is students’ preferences regarding subtitling conditions. Teachers should be aware of how their students watch foreign language films to be able to help them use such materials more effectively.

Karolina Baranowska is a PhD student at the Department of Applied English Linguistics and Language Teaching, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland. Her research interests include second language acquisition, methods of teaching English as a foreign language, and cognitive load theory. She is involved in teaching English as a foreign language at academic level.

Email:[email protected]