-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Aliya Izumi, Grace Lee, Zoya Gomes, Maral Ouzounian, Penelope Adinku, Lorena Montes, Dominique Vervoort, Women in cardiac surgery: a global workforce analysis, European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Volume 67, Issue 1, January 2025, ezae463, https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezae463

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Cardiac surgery remains one of the most gender-imbalanced surgical specialties. Women constitute 6–11% of the North American workforce, while other regional data are scarce. Despite the acknowledged under-representation of women in cardiac surgery globally and evidence that surgeon–patient gender concordance enhances postoperative outcomes, precise figures remain poorly defined. Herein, we provide the 1st global quantification of women cardiac surgeons (WCS) and explore correlates of workforce diversity.

The Cardiothoracic Surgery Network database was queried for cardiac surgeons within each country and cross-validated with external sources. Profile pronouns and the genderize.io application determined surgeon sex. Data were stratified by country, geographical region and national income group, and correlation analyses with socioeconomic and gender parity metrics were performed.

Women constitute 8.0% (1178/14 651) of the international cardiac surgical workforce, with a median of 0.00 WCS per million women (interquartile range: 0.00–0.09). North America (11.4%) and Europe (10.3%) lead regional representation, while East Asia (2.9%) and the Middle East (1.7%) rank lowest. High-income countries (9.9%) have double the proportion of WCS as low- and middle-income countries (4.8%), with a notable absence among low-income countries. Female representation correlates with Gross National Income per capita (τ = 0.39), the Global Gender Gap Index (τ = 0.26) and health expenditure (τ = 0.26).

Improving female representation in cardiac surgery is essential to advancing social justice and overall patient care. Yet, WCS remain a minority worldwide, with the most pronounced disparities in low- and middle-income countries and regions with low Gross National Income, Global Gender Gap Index and health expenditure. Confronting these inequities will require targeted mentorship efforts and addressing country-specific entry barriers, necessitating further research into the unique factors influencing women in low- and middle-income countries.

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease accounts for over 17 million deaths annually, yet 75% of the world lacks sufficient access to cardiac surgical care [1]. This gap is expected to worsen without efforts to expand the global surgery infrastructure, strengthening the discourse within global health agendas to address shortcomings in the cardiac surgical workforce and the importance of establishing workforce registries [2]. The inequitable distribution of cardiac surgeons globally is central to this issue, with high-income countries (HICs) enjoying far greater access to cardiac surgical care (7.15 cardiac surgeons per million population) than low-income countries (LICs) (0.04 cardiac surgeons per million), despite low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) bearing 80% of global cardiovascular disease mortality [1].

Global inequities in the cardiac surgical workforce are further compounded by the underrepresentation of women cardiac surgeons (WCS). Despite gender parity among medical students and an increasing proportion of women in cardiothoracic surgery training programmes, a pervasive glass ceiling exists, with women comprising 6–11% of cardiac surgery staff in North America [3, 4]. These inequities extend throughout the surgical pipeline, with sex-based differences in compensation, promotion and academic leadership opportunities [4–6], notwithstanding evidence that, regardless of patient sex, female surgeons have comparable or better postoperative outcomes than their male counterparts [4, 7].

Although the benefits of gender diversity within healthcare teams are well-documented [8], female representation in the global cardiac surgical workforce remains inadequately defined. Significant disparities in surgical workforces exist between HICs and LMICs, influenced by economic strength, geopolitical context, healthcare systems and societal gender expectations [1], which may further complicate workforce integration for WCS across various countries. Amid growing cardiac surgical volumes [9], the field must prioritize efforts to scale-up the global workforce. Hence, there is an opportunity to achieve a more representative workforce by emphasizing the recruitment and retention of women. Herein, we conduct the 1st comprehensive analysis of the current WCS landscape and explore correlates of workforce diversity in global cardiac surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data sources

This study utilized the Cardiothoracic Surgery Network (CTSNet, www.ctsnet.org), an international database of registered adult and congenital cardiac surgeons, to collect workforce data during January 2024. The CTSNet database is overseen by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, encompassing membership registries from 29 societies. Cardiac surgeons not affiliated with these societies are permitted to register independently [1]. Numerical data were cross-validated with official reports [9–11] and local sources, including WCS from various regions (P.A., L.M., M.O.), with duplicate surgeon records identified and removed. The national overall and female populations of 214 countries were sourced from the 2022 World Bank World Development Indicators and used to calculate population coverage and gender concordance [12]. Sex was identified using profile pronouns and cross-verified with the genderize.io application programming interface, applying an 80% confidence threshold. Subthreshold verifications were marked as uncertainties [e.g. 51 (+4) indicates 51 WCS and 4 uncertainties] and excluded from the above calculations.

Statistical analysis

Data were stratified by country, World Bank region [East Asia and Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, North America, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA)] and income category [HICs: ≥$13 846 Gross National Income (GNI) per capita; upper-middle-income countries: $4466–$13 845; lower-middle-income countries: $1136–$4465; and LICs ≤$1135] [12]. Data were aggregated, presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) and visualized using mapchart.net. Kendall’s tau (τ) correlation analysis was conducted to assess relationships between WCS rates and (i) GNI per capita, (ii) national health expenditure and (iii) the Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI)—a framework introduced by the World Economic Forum to evaluate countries’ progress towards gender parity in economic participation, educational attainment, health and political empowerment [12, 13]. Correlations were interpreted as: negligible (τ ≤ 0.05), weak (τ = 0.06–0.25), moderate (τ = 0.26–0.48), strong (τ = 0.49–0.70) and very strong (τ ≥ 0.71) [14]. Statistical analyses were performed using the ‘ggcorrplot’ R package (version 1.4.1).

RESULTS

Women in the global cardiac surgical workforce

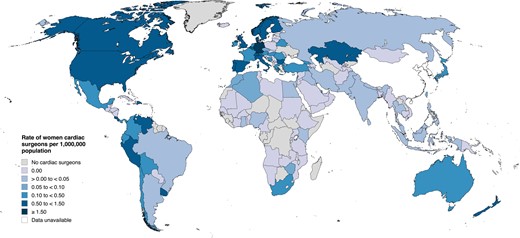

Women constituted 8.0% (1178/14 651) of practicing cardiac surgeons worldwide. Kazakhstan led female representation by this metric [60.0% (12/20)], followed by Barbados [33.3% (1/3)], Bolivia [33.3% (2/6)] and the Dominican Republic [28.9% (13/45)] (Fig. 1, Supplementary Material, Table S1).

Global distribution of women cardiac surgeons as a percentage of the total cardiac surgery workforce in each country. Data were collected from January to May 2024.

Population coverage

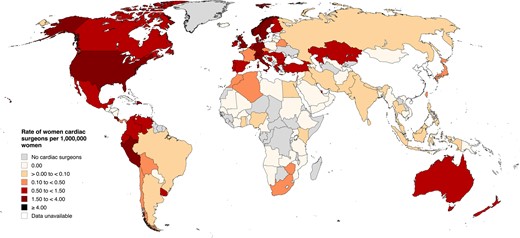

Population coverage (the proportion of WCS per reference population) was 0.15 WCS/million globally, with a national median of 0.00 (IQR: 0.00–0.05). Countries with the highest population coverage were Monaco (54.84 WCS/million), Barbados (3.55/million), Germany (1.83/million) and the USA (1.34/million) (Fig. 2, Supplementary Material, Table S2).

Population coverage rates by country. Population data were extracted from the 2022 World Bank Census.

Gender concordance

Gender concordance describes the number of WCS per female population, indicating the extent to which women have access to women surgeons. Globally, there were 0.30 WCS/million women, with a national median of 0.00 (IQR: 0.00–0.09). Countries with the highest gender concordance were Monaco (107.55/million), Barbados (6.82/million), Germany (3.60/million) and the USA (2.66/million). Comparatively, there were 3.38 male cardiac surgeons/million men globally, with a national median gender concordance of 0.70 (IQR: 0.00–11.19) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Material, Table S3).

Gender concordance rates by country. Female population data were extracted from the 2022 World Bank Census.

Regional and economic trends

While there were no WCS among LICs, women represented 3.6% (61/1678) of cardiac surgeons in lower-middle-income countries, 5.5% (209/3828) in upper-middle-income countries and 9.9% (892/8992) in HICs (Supplementary Material, Table S4). Regionally, 1.7% (14/825) of cardiac surgeons in the Middle East and North Africa were women. Similarly, 2.9% (45/1539) of cardiac surgeons in East Asia and the Pacific were WCS, with the highest proportion in New Zealand. Four percent (39/975) of cardiac surgeons in South Asia were women, comparable with 4.9% (17/345) in SSA. Latin America and the Caribbean, and Europe and Central Asia followed at 5.9% (150/2546) and 10.3% (437/4244) WCS, respectively. North America leads female representation at 11.4% (476/4177), with local medians of 0.72 (IQR: 0.36–1.03) WCS/million and 1.44 (IQR: 0.72–2.05) WCS/million women (Supplementary Material, Table S5).

Correlation analyses

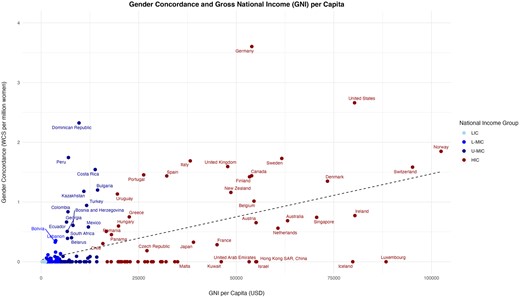

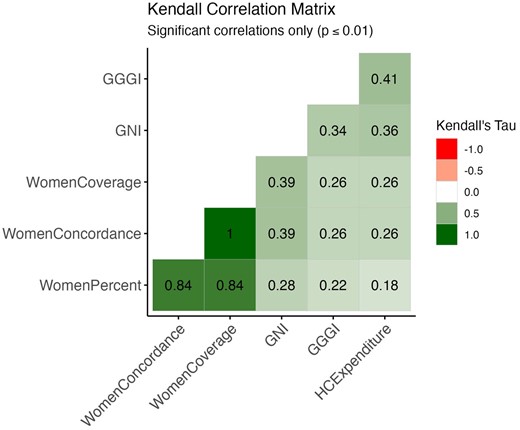

Kendall correlation analysis found a moderate, positive correlation between GGGI gender parity scores and population coverage and gender concordance (τ = 0.26, P < 0.001 for both). Meanwhile, the GGGI displayed a weak, positive correlation with WCS percentage (τ = 0.22, P < 0.01). A moderate, positive correlation was also observed between female representation and GNI per capita, both in terms of national workforce percentage (τ = 0.28, P < 0.001) and population coverage and gender concordance (τ = 0.39, P < 0.001 for both) (Fig. 4). There is a weak, positive correlation between the percentage of WCS and the percentage of Gross Domestic Product allocated to health spending (τ = 0.18, P < 0.001); this relationship strengthened to moderate when considering population coverage and gender concordance (τ = 0.26, P < 0.001 for both). Among the 214 included countries, higher GNI per capita, gender parity and national healthcare investment were associated with increased representation of women in cardiac surgery (Fig. 5).

Scatterplot of cardiac surgeon gender concordance as a function of Gross National Income (GNI) per capita. Each point represents one country and is further identified by its corresponding national income category. Overall trend indicated by a dashed line. HIC: high-income country; LIC: low-income country; L-MIC: lower-middle-income country; U-MIC: upper-middle-income country.

Kendall correlation matrix. Pairwise Kendall tau correlation coefficients for statistically significant relationships (P ≤ 0.01). GGGI: Global Gender Gap Index; GNI: Gross National Income per capita; HCExpenditure: healthcare expenditure.

DISCUSSION

Women remain underrepresented in cardiac surgery. Our study found that WCS account for only 8.0% of nearly 15 000 cardiac surgeons worldwide, a gender imbalance that extends to global population coverage and gender concordance. Although ubiquitous, these disparities vary across national income groups and world regions, with female representation correlating strongest with GNI per capita. Regional sub-analyses reveal that North America, and Europe and Central Asia have the highest proportion of WCS at 11.4% and 10.3%, respectively. Meanwhile, representation remains limited in East Asia and the Pacific (2.9%) and the Middle East and North Africa (1.7%). Collectively, these figures substantiate the recognized gender imbalance within cardiac surgery and highlight the complex intersection of female representation with national economic strength, geopolitical context and sociocultural influences, as no single variable demonstrated a strong independent correlation with WCS rates.

Women occupy only 8.0% of cardiac surgeon positions worldwide, strikingly lower than matriculating medical students (50–60%) and cardiothoracic surgery residents (20%) [15–17]. Cardiac surgery has also seen the slowest increase in female surgeons compared to all other surgical specialties in Canada (0.18% per year) and is forecasted to reach gender parity in 2 centuries compared to a few decades in general surgery and 1 century for neurosurgery and orthopaedics [17]. This disparity raises potential concerns in light of the established association between gender discordance and worse postoperative outcomes for female patients treated by male surgeons [7]. Importantly, there is no corresponding negative effect for male patients treated by female surgeons, who potentially yield better surgical outcomes overall, including reductions in mortality and readmission rates, improved accuracy in risk and severity assessments, greater diagnostic certainty and more positively rated patient encounters [4, 7]. Furthermore, male physicians with greater exposure to female physicians were more effective in treating female patients after myocardial infarction, highlighting the universal benefits of gender-balanced healthcare teams, and the positive influence female physicians can have on their male colleagues [18]. These findings underscore the clinical relevance of gender concordance and population coverage in the context of WCS, especially since female patients already face worse prognoses and higher relative risks of developing cardiovascular disease than men with comparable risk profiles [19].

The observed variability across geographical regions and income groups highlights the global heterogeneity of WCS and their barriers to entry. We 1st stratified the data by national income group, acknowledging the influence of economic prosperity on surgical infrastructure and that the total number of cardiac surgeons closely follows countries’ Gross Domestic Product [1]. Our analysis revealed that WCS representation correlates with GNI per capita, with women comprising 0.0%, 3.6%, 5.5% and 9.9% of cardiac surgical workforces in LICs, lower-middle-income countries, upper-middle-income countries and HICs, respectively, consistent with a slower observed rise of female surgeons in LMICs than in other specialties [20].

Cultural and political attitudes towards gender equity can independently shape WCS distribution, warranting consideration for the GGGI gender parity index. North America displayed the highest WCS representation, consistent with its high GGGI ranking. Despite an advanced cardiac surgery infrastructure and high educational attainment for women, economic parity remains an issue, with North American WCS earning significantly less than their male colleagues and cardiac surgery having the largest gender wage gap of all the surgical specialties in Canada [4, 21]. Xepoleas et al. further highlighted several pregnancy-related challenges for female surgeons, including negative judgements of competency and pressures to schedule pregnancies around training. Interestingly, 79% of surgical residents in SSA reported having children during training, compared to only 28% in the USA, which they attributed to less childbearing stigma and more multi-generational households that provide greater familial support networks to WCS with childcare responsibilities [20]. Conversely, historical attitudes towards female education, the absence of paid paternity leave and limited cardiothoracic surgical training opportunities continue to hinder equitable representation of WCS in SSA [22, 23]. In Europe and Central Asia, which ranks 2nd in female representation and 1st in the GGGI, work–life balance is the most common deterrent to WCS, including limited part-time career availability and work–family conflicts [3, 20, 24]. Meanwhile, the Middle East and North Africa have the lowest GGGI rank and gender concordance in cardiac surgery, consistent with literature describing how traditional gender norms in these countries may discourage women from pursuing the specialty [25]. Notably, some HICs rank low in both gender concordance and GGGI despite economic affluence. For instance, Japan and other East Asian countries ranked in the bottom 50% of the GGGI and were found to have some of the lowest gender concordance rates among HICs. Female surgeons in Japan report significant cultural barriers to entry, including less family support for their careers and conflicts between domestic duties and surgical demands [26]. These examples highlight how cultural attitudes towards gender can create unique challenges for WCS beyond national economies and may help explain why East Asia and the Middle East exhibit poorer gender concordance than SSA despite their higher economic ranks.

Beyond regional factors, the issue of gender equity in cardiac surgery is universal and perpetuated by broader systemic issues. The under-representation of WCS is a product of serial challenges throughout the surgical pipeline that contribute to higher rates of burnout and attrition among women [27]. Women leave residency and fellowship programmes more frequently and face lower certification rates and advancement opportunities than men, occupying only 4% of cardiothoracic professorships in Italy and 30% of leadership positions within cardiovascular societies and editorial boards in Canada [3, 4, 28]. Women also receive fewer referrals and more significant financial repercussions following medical errors [4, 16, 21]. A considerable gender wage gap reinforces these inequities, with WCS earning 70–80% of male salaries despite similar operative hours and outcomes [4, 21]. Italy, with one of the smallest gender pay gaps in Europe [3] and one of the highest gender concordance rates reported, illustrates how improving financial compensation for women may help increase female representation within cardiac surgical teams.

Work–life balance and family planning remain significant concerns, with 65% of WCS reporting that their careers impacted their family planning decisions [15]. Both male and female surgeons agree that women face more professional disadvantages upon starting a family [16]. This sentiment is supported by 98% of WCS versus 50% of men delaying pregnancy and 82% of women versus 60% of men feeling that their careers would be negatively affected by pregnancy [29, 30]. In recognition of these issues, programmes should offer more inclusive family leave policies and increase childbearing support measures such as on-site childcare facilities [4, 16].

Limited female mentorship is the most consistent and universally cited barrier by WCS [20]. The impact of mentorship is well-documented, with 80% of cardiac surgery residents endorsing its significance in specialty selection, particularly among female trainees [4, 31]. Correspondingly, Ahmadiyeh et al. [32] found that having female role models in surgical departments increases the likelihood of female students pursuing surgery. Like mentorship, WCS visibility is crucial to inspiring the next generation of surgeons. Women groups within professional surgical societies are particularly effective in this regard, including the Women in Thoracic Surgery organization and EACTS Women in Cardiothoracic Surgery Committee, which helped increase female involvement at recent Annual Meetings by 11.5% and 4.6% among session leaders and abstract presenters, respectively [33–35]. Awards and grants, such as the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Women in Cardiovascular Medicine Mentorship Award, enhance the visibility and recognition of female surgeons [4]. Furthermore, with 146/214 countries lacking WCS entirely, digital platforms and social media can enhance trainee networking capacity and exposure to same-sex cardiac surgeon mentors [36].

The male-dominated culture of surgery presents additional challenges for the female trainee, with a recent study reporting that 96% of females, compared to 0% of male students, view surgery as ‘unfavourable to their gender’ [16]. Confronting this issue requires male allyship in addition to expanding female leadership in cardiac surgery [4]. Evidence from Turkey indicates that female surgical trainees are more likely to experience gender-based discrimination in departments lacking female faculty [20]. Similarly, a Colombian case study showed that introducing a female cardiothoracic surgery programme director improved the workplace environment for female surgical staff [11]. These examples point to the potential for a positive feedback loop whereby increasing female leadership in cardiac surgery encourages more gender-inclusive environments that promote the inclusion of more WCS.

Limitations

These findings should be considered in the context of certain limitations. First, not all practicing cardiac surgeons are featured in the CTSNet database. Although additional resources and local surgeons were consulted to supplement this registry, underestimates may persist. Given that male and female surgeons register through the same channels, these underestimates are likely to influence the absolute number of surgeons without compromising the accuracy of relative values. However, women often face unique structural and intrinsic barriers that limit their involvement in professional networks [37], which may result in their disproportionate absence from this registry, and some countries incorrectly deemed to have no WCS. This limitation reveals workforce registries as another facet of gender imbalance in cardiac surgery and highlights the need for more equitable enrolment strategies and academic discourse surrounding this topic. The CTSNet database also integrates regional datasets with a bias towards HICs and anglophone regions, leading to more significant underestimates in LMICs where CTSNet registration is voluntary, and English is less commonly spoken. Additionally, while genderize.io was used to determine gender from surgeon names objectively, it contains cultural biases with more uncertainties in East Asian countries that were consequently excluded from rate calculations, leading to more potential underestimations in this region. This study also focused on biological sex as a binary variable rather than exploring all forms of gender identity or expression. Thus, a more nuanced investigation of surgeon gender, including any changes in gender identity since medical licensure, is warranted. Cardiothoracic, cardiovascular and cardiac surgery have also been aggregated for these analyses; as such, our study does not capture nuances between specialization pathways. Finally, national WCS percentages are heavily impacted by the surgeon pool size [e.g. Barbados at 33.3% (1/3)], resulting in outliers that may weaken correlations with the GGGI and health expenditure.

CONCLUSIONS

This study represents an inaugural attempt to quantify the global representation of women in cardiac surgery, providing an empirical basis for addressing the persistent gender disparities in the field and exploring their underlying causes. Our data reveal a higher representation of WCS in HICs than in LMICs, highlighting the role of national economies in shaping access and opportunities for women in the field. Regional interpretations of the data offer critical sociocultural insights to help inform tailored approaches to gender parity in regional workforces. These findings highlight the need for improved workforce data collection to enable global benchmarking and progress monitoring in cardiac surgery and emphasize the importance of equity, diversity and inclusion in the continued innovation and advancement of cardiac surgery around the world.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at EJCTS online.

FUNDING

D.V. is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship for work outside this manuscript. M.O. is partially supported by the Munk Chair in Advanced Therapeutics and the Antonio & Helga DeGasperis Chair in Clinical Trials and Outcomes Research.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data are made publicly available in the tables and supplementary materials.

Author contributions

Aliya Izumi: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Visualization; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. Grace Lee: Conceptualization; Data curation; Methodology; Project administration; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. Zoya Gomes: Conceptualization; Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Writing—review & editing. Maral Ouzounian: Supervision; Validation; Writing—review & editing. Penelope Adinku: Data curation; Investigation; Validation; Writing—review & editing. Lorena Montes: Data curation; Investigation; Validation; Writing—review & editing. Dominique Vervoort: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing.

Reviewer information

European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery thanks Johanna J.M. Takkenberg, Anita Nguyen and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review process of this article.

Presented at the 38th Annual EACTS Meeting, Lisbon, Portugal, October 2024.

REFERENCES

ABBREVIATIONS

- CTSNet

Cardiothoracic Surgery Network

- EACTS

European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery

- GGGI

Global Gender Gap Index

- GNI

Gross National Income

- HIC

High-income country

- IQR

Interquartile range

- LIC

Low-income country

- LMICs

Low- and middle-income countries

- SSA

Sub-Saharan Africa

- WCS

Women cardiac surgeon

Author notes

Aliya Izumi and Grace Lee authors contributed equally to this work.