-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Thomas Galetin, Christoph Eckermann, Jerome M Defosse, Olger Kraja, Alberto Lopez-Pastorini, Julika Merres, Aris Koryllos, Erich Stoelben, Patients’ satisfaction with local and general anaesthesia for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery—results of the first randomized controlled trial PASSAT, European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Volume 63, Issue 2, February 2023, ezad046, https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezad046

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The objective of this single-centre, open, randomized control trial was to compare the patients’ satisfaction with local anaesthesia (LA) or general anaesthesia (GA) for video-assisted thoracoscopy.

Patients with indication for video-assisted thoracoscopy pleural management, mediastinal biopsies or lung wedge resections were randomized for LA or GA. LA was administered along with no or mild sedation and no airway devices maintaining spontaneous breathing, and GA was administered along with double-lumen tube and one-lung ventilation. The primary end point was anaesthesia-related satisfaction according to psychometrically validated questionnaires. Patients not willing to be randomized could attend based on their desired anaesthesia, forming the preference arm.

Fifty patients were allocated to LA and 57 patients to GA. Age, smoking habits and lung function were similarly distributed in both groups. There was no significant difference between the 2 groups with regard to patient satisfaction with anaesthesiology care (median 2.75 vs 2.75, P = 0.74), general perioperative care (2.50 vs 2.50, P = 0.57), recovery after surgery (2.00 vs 2.00, P = 0.16, 3-point Likert scales). Surgeons and anaesthesiologists alike were less satisfied with feasibility (P < 0.01 each) with patients in the LA group. Operation time, postoperative pain scales, delirium and complication rate were similar in both groups. LA patients had a significantly shorter stay in hospital (mean 3.9 vs 6.0 days, P < 0.01). Of 18 patients in the preference arm, 17 chose LA, resulting in similar satisfaction.

Patients were equally satisfied with both types of anaesthesia, regardless of whether the type of anaesthesia was randomized or deliberately chosen. LA is as safe as GA but correlated with shorter length of stay. Almost all patients of the preference arm chose LA. Considering the benefits of LA, it should be offered to patients as an equivalent alternative to GA whenever medically appropriate and feasible.

INTRODUCTION

Thoracic surgery has been facilitated by anaesthesiologic techniques enabling one-lung ventilation (OLV). However, deep general anaesthesia (GA) and OLV negatively impact pulmonary and systemic inflammatory processes, particularly in elderly and comorbid patients. Thus, there are increasing efforts in less invasive anaesthesiologic techniques, using local anaesthesia (LA) and sedation, and maintaining spontaneous breathing; these are usually called AVATS or NiVATS [awake or non-intubated video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS), respectively], depending on the depth of sedation, and are—in turn—facilitated by modern less invasive surgical techniques [1].

While there is decent evidence of the safety, feasibility and pathophysiological advantages of non-intubated VATS [2–4], the patient’s perspective has not been examined, yet. Analogue to other surgical disciplines, patients are usually not explained or offered different types of anaesthesia; instead, the decision is made by the treating physicians [5]. While we can counsel patients on the physiological properties of LA and GA, we do not know if they will be equally satisfied. As shared decision-making is known to increase the patients’ confidence, improve their therapy adherence and quality of life, enhance the communication between healthcare providers and patients, reduce healthcare costs and ameliorate the patients’ outcomes, finding the ‘right’ type of anaesthesia should be part of it [6, 7]. This randomized controlled trial has been conducted to contribute to the knowledge on the patients’ satisfaction related to anaesthesia. We focussed on the question whether patients differ in their anaesthesia-related satisfaction depending on the type of anaesthesia.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the ethic commission of University Witten/Herdecke, Germany, under approval number 195/2017. Written consent was obtained from all participants before inclusion.

Study design

The detailed study protocol has been published [8]. PASSAT was a single-centre, open, randomized controlled trial with an un-randomized, preference-based side-arm, conducted at the thoracic surgery department of the Lung Clinic Cologne-Merheim, Germany, registry ID DRKS00013661. The primary end point was to assess the satisfaction related to LA or GA in patients who underwent minor VATS; for this purpose, patients were randomly assigned to LA or GA (randomized study arm). Patients who did not want to be randomized were asked to attend based on their free choice of anaesthesia type, forming the preference arm of the study. Randomized patients were analysed in an intention-to-treat principle; they were excluded from analysis if they withdrew their consent to participate (dropout).

End points

The primary end point was assessed using a validated questionnaire (ANP [9]). The questionnaire contains 46 items in 2 parts, each answered on a 3-point Likert scale, with 0 indicating the least and 3 indicating the maximum satisfaction. ‘Part 1 assesses the intensity of symptoms regarding the postoperative period in the “recovery-room and the first hours on the ward” (19 items) and the “current state” (17 items). Part 2 assesses patient satisfaction with the anaesthetic care as well as the unspecific perioperative care and postoperative convalescence’, forming 3 scores, of which the first one represents our primary end point [9]. The answers were correlated to preoperative scores for depression, anxiety (HADS-D [10]) and pain sensitivity (PSQ [11]) using linear correlation (Pearson’s r), as these factors were shown to influence postoperative satisfaction [10, 12]. Anaesthesiologists and surgeons answered 4 questions on their satisfaction with the operation and anaesthesiologic regime immediately after surgery (10-point Likert scales).

Patients and procedures

VATS indications were pleural management (biopsies, pleurodesis, permanent drainage), mediastinal biopsies, pericardiac window and lung wedge resection. Eligible patients had to be suitable for both types of anaesthesia so that patients can be converted from LA to GA in case of difficulties during surgery. Patients with previous ipsilateral thoracic surgery or radiation, severe COPD (FEV1 <30%), difficult airway and emergent operation were excluded. LA and GA were performed using the same anaesthetic medicaments to provide for maximal comparability: Patients of both groups received Midazolam p.o. 1 h before surgery and got local infiltration of the surgery site with 1% mepivacaine by the surgeon. One to three trocars or 1 mini thoracotomy were used; the number of affected intercostal spaces was documented. LA patients were sedated with remifentanil and, if necessary, propofol; mild to conscious sedation was aimed at. Spontaneous breathing was maintained without upper airway devices. GA patients were inducted with remifentanil, propofol and rocuronium; surgery was performed under OLV using a double-lumen tube. No peridural catheters or other anaesthesiologic methods were used in neither group. The postoperatively administered analgetic drugs were documented and transformed to morphine-equivalent doses.

The patients were monitored with arterial blood gas analysis during, 30 min and 60 min after the operation.

Sample size calculation

‘The null hypothesis is that patients with LA are as satisfied with anaesthesia according to the “satisfaction with anaesthesia” score of the ANP as those with GA. The alternative hypothesis is that satisfaction in both groups is not equal. The score is noted on an ordinal scale from 0 to 3. The mean satisfaction in the evaluation study was μ = 2.58 with a standard deviation of σ = 0.54 [9]. A difference of satisfaction of ϵ = 0.32 point is defined as clinically relevant, resulting in a mid-scale effect size ϵ/σ = 0.59. With a significance level of α = 5%, a power of (1 − β) = 80% and an allocation rate of 1:1, we need patients in each randomized group [13]. Since the ANP satisfaction scale is ordinal, we correct the sample size by +10%’ [8]. Thus, we had calculated 2 × 50 patients to be randomized to detect a difference of satisfaction of 0.32 points on a 3-point Likert scale (Smallest Effect Size of Interest, SESOI [14], corresponding to a mild-scale effect size, Cohen’s d 0.59). Randomization (with a variable block size of 2, 4 and 6) and data capture were conducted using an approved web-based electronic data capture program (CASTOR EDC, Netherlands [15]).

Descriptive and analytic statistics

Descriptive and analytic statistics were performed with R version 4.2.0 [16]. The central values of the normally distributed quantitative variables are reported with mean and standard deviation, while not-normally distributed quantitative variables are presented as median (1st quartile, 3rd quartile). Normality was examined using histograms and Shapiro–Wilk-test. For normally distributed variables, the differences between groups were compared with the Student's t-test; otherwise, we used the nonparametric Wilcox–Mann–Whitney U-test. Proportions/frequencies between groups were compared with the Chi-squared test. Equivalence was tested upon the reviewers’ requests by comparing the 90% confidence interval of the measured effect with the above specified SESOI and confirmed by two one-sided test approach, using R-package TOSTER [17, 18]. However, this was not a non-inferiority or equivalence trial.

RESULTS

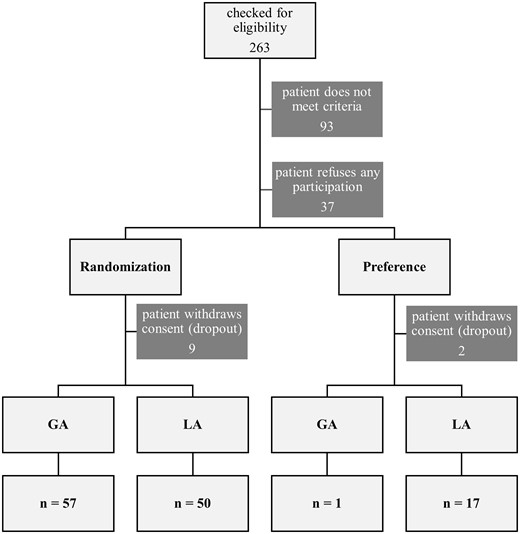

Patients were recruited from June 2018 to September 2021. In total, 263 patients were screened. For LA and GA, after dropouts, 50 and 57 patients were included in the randomized arm and 17 and 1 in the preference arm, respectively. Fifty-three patients refused participation, and 11 withdrew their consent. Reasons for exclusion were that patients were deemed not suitable for surgical reasons (for example central pulmonary nodules) (36), ipsilateral pretreatment (18), language barriers (12), patients cognitively not capable of answering the questionnaires or consent (9) and other reasons (17) (Figure 1). The basic patient characteristics were similar in both groups and are presented in Table 1.

| Basic data . | LA, n = 50 . | GA, n = 57 . | p-Value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 67 ± 12 | 67 ± 11 | 0.9w |

| BMI (kg/m²), mean ± SD | 26 ± 4 | 26 ± 5 | 0.8w |

| Smoker (%) | 0.2 | ||

| Never | 40 | 22 | |

| Former | 26 | 46 | |

| Active | 35 | 31 | |

| Packyears, mean ± SD | 37 ± 20 | 38 ± 21 | 0.8t |

| ASA, median (1st, 3rd quartile) | 3 (3, 3) | 3 (3, 3) | |

| FEV1 (%), mean ± SD | 70 ± 18 | 70 ± 20 | 0.8t |

| Kco(Hb) (%), mean ± SD | 84 ± 20 | 80 ± 22 | 0.5t |

| Operation | 0.2 | ||

| Pleural biopsy | 21 | 31 | |

| Pulmonary wedge resection | 15 | 15 | |

| Pleurodesis | 11 | 7 | |

| Other | 2 | 4 |

| Basic data . | LA, n = 50 . | GA, n = 57 . | p-Value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 67 ± 12 | 67 ± 11 | 0.9w |

| BMI (kg/m²), mean ± SD | 26 ± 4 | 26 ± 5 | 0.8w |

| Smoker (%) | 0.2 | ||

| Never | 40 | 22 | |

| Former | 26 | 46 | |

| Active | 35 | 31 | |

| Packyears, mean ± SD | 37 ± 20 | 38 ± 21 | 0.8t |

| ASA, median (1st, 3rd quartile) | 3 (3, 3) | 3 (3, 3) | |

| FEV1 (%), mean ± SD | 70 ± 18 | 70 ± 20 | 0.8t |

| Kco(Hb) (%), mean ± SD | 84 ± 20 | 80 ± 22 | 0.5t |

| Operation | 0.2 | ||

| Pleural biopsy | 21 | 31 | |

| Pulmonary wedge resection | 15 | 15 | |

| Pleurodesis | 11 | 7 | |

| Other | 2 | 4 |

w: Wilcox–Mann–Whitney U-test; t: Student’s t-test.

GA: general anaesthesia; LA: local anaesthesia; SD: standard deviation

| Basic data . | LA, n = 50 . | GA, n = 57 . | p-Value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 67 ± 12 | 67 ± 11 | 0.9w |

| BMI (kg/m²), mean ± SD | 26 ± 4 | 26 ± 5 | 0.8w |

| Smoker (%) | 0.2 | ||

| Never | 40 | 22 | |

| Former | 26 | 46 | |

| Active | 35 | 31 | |

| Packyears, mean ± SD | 37 ± 20 | 38 ± 21 | 0.8t |

| ASA, median (1st, 3rd quartile) | 3 (3, 3) | 3 (3, 3) | |

| FEV1 (%), mean ± SD | 70 ± 18 | 70 ± 20 | 0.8t |

| Kco(Hb) (%), mean ± SD | 84 ± 20 | 80 ± 22 | 0.5t |

| Operation | 0.2 | ||

| Pleural biopsy | 21 | 31 | |

| Pulmonary wedge resection | 15 | 15 | |

| Pleurodesis | 11 | 7 | |

| Other | 2 | 4 |

| Basic data . | LA, n = 50 . | GA, n = 57 . | p-Value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 67 ± 12 | 67 ± 11 | 0.9w |

| BMI (kg/m²), mean ± SD | 26 ± 4 | 26 ± 5 | 0.8w |

| Smoker (%) | 0.2 | ||

| Never | 40 | 22 | |

| Former | 26 | 46 | |

| Active | 35 | 31 | |

| Packyears, mean ± SD | 37 ± 20 | 38 ± 21 | 0.8t |

| ASA, median (1st, 3rd quartile) | 3 (3, 3) | 3 (3, 3) | |

| FEV1 (%), mean ± SD | 70 ± 18 | 70 ± 20 | 0.8t |

| Kco(Hb) (%), mean ± SD | 84 ± 20 | 80 ± 22 | 0.5t |

| Operation | 0.2 | ||

| Pleural biopsy | 21 | 31 | |

| Pulmonary wedge resection | 15 | 15 | |

| Pleurodesis | 11 | 7 | |

| Other | 2 | 4 |

w: Wilcox–Mann–Whitney U-test; t: Student’s t-test.

GA: general anaesthesia; LA: local anaesthesia; SD: standard deviation

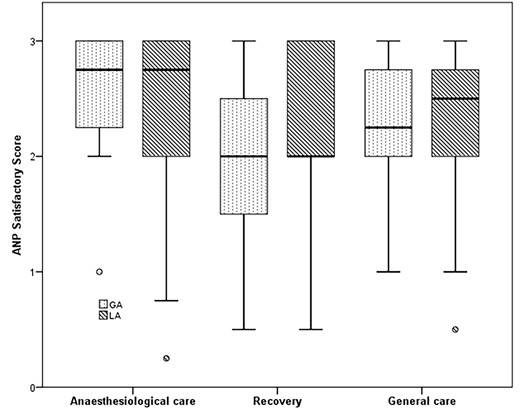

The primary end point of satisfaction with anaesthesiologic care according to the ANP score was not statistically different between the groups [LA 2.75 (2.00, 3.00) vs GA 2.75 (2.25, 3.00), respectively, P = 0.74]. The 90% confidence interval of the effect [−0.00, 0.25] lies within the pre-specified range of difference of interest, which was [−0.32, 0.32] (SESOI [14]), indicating equivalence (P = 0.0001). The ANP also has scores for other aspects of patients’ satisfaction, i.e. satisfaction with general care [2.50 (2.00, 2.75) each, P = 0.57] and with their own recovery [2.00 (2.00, 2.63) vs 2.00 (1.50, 2.25), P = 0.16]. These differences were also not statistically significant between the 2 groups (Figure 2). Satisfaction did not correlate with preoperative scores for anxiety, depression or pain sensitivity, nor with the number of intercostal spaces affected by trocars or mini thoracotomy during surgery (data not shown).

Comparison of anaesthesia-related satisfaction of patients randomized to general anaesthesia or local anaesthesia.

Surgeons were less satisfied with lung collapse, overall feasibility, coughing and pressing in LA than in GA, while the anaesthesiologists were less satisfied with the patient’s anxiety and overall feasibility, but not with coughing and pressing (Table 2).

Practitioners’ satisfaction with the patient being operated in local anaesthesia or general anaesthesia

| Practitioners’ satisfaction . | LA . | GA . | P-Value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anaesthetist’s satisfaction with | |||

| Patient’s anxiety | 7.5 ± 3.0 | 9.6 ± 1.1 | 0.002w |

| Feasibility | 7.4 ± 3.0 | 9.0 ± 1.7 | 0.033w |

| Coughing | 8.7 ± 2.6 | 8.9 ± 2.2 | 0.67w |

| Pressing | 8.7 ± 2.5 | 9.0 ± 1.9 | 0.65w |

| Surgeon’s satisfaction with | |||

| Lung collapse | 7.8 ± 2.6 | 9.0 ± 2.4 | 0.002w |

| Feasibility | 7.7 ± 3.1 | 9.4 ± 1.7 | <0.001w |

| Coughing | 7.9 ± 3.1 | 9.6 ± 1.3 | <0.001w |

| Pressing | 7.3 ± 3.5 | 9.5 ± 1.5 | <0.001w |

| Practitioners’ satisfaction . | LA . | GA . | P-Value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anaesthetist’s satisfaction with | |||

| Patient’s anxiety | 7.5 ± 3.0 | 9.6 ± 1.1 | 0.002w |

| Feasibility | 7.4 ± 3.0 | 9.0 ± 1.7 | 0.033w |

| Coughing | 8.7 ± 2.6 | 8.9 ± 2.2 | 0.67w |

| Pressing | 8.7 ± 2.5 | 9.0 ± 1.9 | 0.65w |

| Surgeon’s satisfaction with | |||

| Lung collapse | 7.8 ± 2.6 | 9.0 ± 2.4 | 0.002w |

| Feasibility | 7.7 ± 3.1 | 9.4 ± 1.7 | <0.001w |

| Coughing | 7.9 ± 3.1 | 9.6 ± 1.3 | <0.001w |

| Pressing | 7.3 ± 3.5 | 9.5 ± 1.5 | <0.001w |

Pressing is contractions of the diaphragm, mediastinum and even whole body when manipulating the lung or bronchi. Both anaesthesiologists and surgeons were more satisfied with GA. Notice that while surgeons felt uncomfortable with the patient coughing and pressing in LA, the anaesthesiologists did not. Data shown as mean ± standard deviation. w: Wilcox–Mann–Whitney U-test.

GA: general anaesthesia; LA: local anaesthesia.

Practitioners’ satisfaction with the patient being operated in local anaesthesia or general anaesthesia

| Practitioners’ satisfaction . | LA . | GA . | P-Value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anaesthetist’s satisfaction with | |||

| Patient’s anxiety | 7.5 ± 3.0 | 9.6 ± 1.1 | 0.002w |

| Feasibility | 7.4 ± 3.0 | 9.0 ± 1.7 | 0.033w |

| Coughing | 8.7 ± 2.6 | 8.9 ± 2.2 | 0.67w |

| Pressing | 8.7 ± 2.5 | 9.0 ± 1.9 | 0.65w |

| Surgeon’s satisfaction with | |||

| Lung collapse | 7.8 ± 2.6 | 9.0 ± 2.4 | 0.002w |

| Feasibility | 7.7 ± 3.1 | 9.4 ± 1.7 | <0.001w |

| Coughing | 7.9 ± 3.1 | 9.6 ± 1.3 | <0.001w |

| Pressing | 7.3 ± 3.5 | 9.5 ± 1.5 | <0.001w |

| Practitioners’ satisfaction . | LA . | GA . | P-Value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anaesthetist’s satisfaction with | |||

| Patient’s anxiety | 7.5 ± 3.0 | 9.6 ± 1.1 | 0.002w |

| Feasibility | 7.4 ± 3.0 | 9.0 ± 1.7 | 0.033w |

| Coughing | 8.7 ± 2.6 | 8.9 ± 2.2 | 0.67w |

| Pressing | 8.7 ± 2.5 | 9.0 ± 1.9 | 0.65w |

| Surgeon’s satisfaction with | |||

| Lung collapse | 7.8 ± 2.6 | 9.0 ± 2.4 | 0.002w |

| Feasibility | 7.7 ± 3.1 | 9.4 ± 1.7 | <0.001w |

| Coughing | 7.9 ± 3.1 | 9.6 ± 1.3 | <0.001w |

| Pressing | 7.3 ± 3.5 | 9.5 ± 1.5 | <0.001w |

Pressing is contractions of the diaphragm, mediastinum and even whole body when manipulating the lung or bronchi. Both anaesthesiologists and surgeons were more satisfied with GA. Notice that while surgeons felt uncomfortable with the patient coughing and pressing in LA, the anaesthesiologists did not. Data shown as mean ± standard deviation. w: Wilcox–Mann–Whitney U-test.

GA: general anaesthesia; LA: local anaesthesia.

There were no statistical differences in the secondary outcomes pain, chest tube time, surgery time and complication rate, but LA patients left the hospital 2 days earlier than GA patients (3.9 ± 2.0 vs 6.0 ± 4.4, P = 0.022; Table 3). In LA patients, the average length of hospital stay was shorter than the chest tube time. There was no difference in postoperative morphine-equivalent doses of analgetic drugs (1175 ± 571 vs 1093 ± 692 mg, P = 0.76, Wilcox test).

| Postoperative outcome . | LA random . | GA random . | P-Value . | LA pref. . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANP score for satisfaction | ||||

| Anaesthetic care | 2.75 (2.00, 3.00) | 2.75 (2.25, 3.00) | 0.74w | 2.75 (2.225, 3.00) |

| General care | 2.50 (2.00, 2.75) | 2.50 (2.00, 2.75) | 0.57w | 2.50 (2.00, 3.00) |

| Recovery | 2.00 (2.00, 2.63) | 2.00 (1.50, 2.25) | 0.16w | 2.00 (2.00, 3.00) |

| Secondary end points | ||||

| Pain NRS day 1 | 2.7 ± 2.5 | 2.2 ± 2.4 | 0.33w | 2.0 ± 2.1 |

| Pain NRS day 5 | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 0.36w | 0 |

| Chest tube time (days) | 5.0 ± 11.8 | 3.9 ± 3.3 | 0.14w | 2.8 ± 2.2 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 3.9 ± 2.0 | 6.0 ± 4.4 | 0.022w | 3.3 ± 1.9 |

| Surgery time (min) | 35 ± 27 | 33 ± 20 | 0.69w | 29 ± 11 |

| Conversion rate LA to GA | 1/50 | – | – | – |

| Complication rate | 0/50 | 3/57 | 0.29 | 0/17 |

| Postoperative outcome . | LA random . | GA random . | P-Value . | LA pref. . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANP score for satisfaction | ||||

| Anaesthetic care | 2.75 (2.00, 3.00) | 2.75 (2.25, 3.00) | 0.74w | 2.75 (2.225, 3.00) |

| General care | 2.50 (2.00, 2.75) | 2.50 (2.00, 2.75) | 0.57w | 2.50 (2.00, 3.00) |

| Recovery | 2.00 (2.00, 2.63) | 2.00 (1.50, 2.25) | 0.16w | 2.00 (2.00, 3.00) |

| Secondary end points | ||||

| Pain NRS day 1 | 2.7 ± 2.5 | 2.2 ± 2.4 | 0.33w | 2.0 ± 2.1 |

| Pain NRS day 5 | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 0.36w | 0 |

| Chest tube time (days) | 5.0 ± 11.8 | 3.9 ± 3.3 | 0.14w | 2.8 ± 2.2 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 3.9 ± 2.0 | 6.0 ± 4.4 | 0.022w | 3.3 ± 1.9 |

| Surgery time (min) | 35 ± 27 | 33 ± 20 | 0.69w | 29 ± 11 |

| Conversion rate LA to GA | 1/50 | – | – | – |

| Complication rate | 0/50 | 3/57 | 0.29 | 0/17 |

ANP scores are presented as median (1st quartile, 3rd quartile), secondary end points are presented as mean ± standard deviation and proportions. w: Wilcox–Mann–Whitney U-test.

GA: general anaesthesia; LA: local anaesthesia.

Bold values represent statistical significance.

| Postoperative outcome . | LA random . | GA random . | P-Value . | LA pref. . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANP score for satisfaction | ||||

| Anaesthetic care | 2.75 (2.00, 3.00) | 2.75 (2.25, 3.00) | 0.74w | 2.75 (2.225, 3.00) |

| General care | 2.50 (2.00, 2.75) | 2.50 (2.00, 2.75) | 0.57w | 2.50 (2.00, 3.00) |

| Recovery | 2.00 (2.00, 2.63) | 2.00 (1.50, 2.25) | 0.16w | 2.00 (2.00, 3.00) |

| Secondary end points | ||||

| Pain NRS day 1 | 2.7 ± 2.5 | 2.2 ± 2.4 | 0.33w | 2.0 ± 2.1 |

| Pain NRS day 5 | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 0.36w | 0 |

| Chest tube time (days) | 5.0 ± 11.8 | 3.9 ± 3.3 | 0.14w | 2.8 ± 2.2 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 3.9 ± 2.0 | 6.0 ± 4.4 | 0.022w | 3.3 ± 1.9 |

| Surgery time (min) | 35 ± 27 | 33 ± 20 | 0.69w | 29 ± 11 |

| Conversion rate LA to GA | 1/50 | – | – | – |

| Complication rate | 0/50 | 3/57 | 0.29 | 0/17 |

| Postoperative outcome . | LA random . | GA random . | P-Value . | LA pref. . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANP score for satisfaction | ||||

| Anaesthetic care | 2.75 (2.00, 3.00) | 2.75 (2.25, 3.00) | 0.74w | 2.75 (2.225, 3.00) |

| General care | 2.50 (2.00, 2.75) | 2.50 (2.00, 2.75) | 0.57w | 2.50 (2.00, 3.00) |

| Recovery | 2.00 (2.00, 2.63) | 2.00 (1.50, 2.25) | 0.16w | 2.00 (2.00, 3.00) |

| Secondary end points | ||||

| Pain NRS day 1 | 2.7 ± 2.5 | 2.2 ± 2.4 | 0.33w | 2.0 ± 2.1 |

| Pain NRS day 5 | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 0.36w | 0 |

| Chest tube time (days) | 5.0 ± 11.8 | 3.9 ± 3.3 | 0.14w | 2.8 ± 2.2 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 3.9 ± 2.0 | 6.0 ± 4.4 | 0.022w | 3.3 ± 1.9 |

| Surgery time (min) | 35 ± 27 | 33 ± 20 | 0.69w | 29 ± 11 |

| Conversion rate LA to GA | 1/50 | – | – | – |

| Complication rate | 0/50 | 3/57 | 0.29 | 0/17 |

ANP scores are presented as median (1st quartile, 3rd quartile), secondary end points are presented as mean ± standard deviation and proportions. w: Wilcox–Mann–Whitney U-test.

GA: general anaesthesia; LA: local anaesthesia.

Bold values represent statistical significance.

One of 50 LA patients had to be converted to GA during the operation. LA patients were hypercapnic and acidic at the end of operation according to BGA, which revealed within 30 min. GA patients were hyperoxygenated and normocapnic at the end of operation (Table 4).

| Arterial blood gas analysis . | LA . | GA . | P-Valuew . |

|---|---|---|---|

| pO2, mean ± SD | |||

| At the end of operation | 104 ± 50 | 173 ± 116 | 0.02 |

| 30 min after operation | 92 ± 26 | 89 ± 32 | 0.34 |

| 60 min after operation | 93 ± 25 | 89 ± 24 | 0.18 |

| pCO2, mean ± SD | |||

| At the end of operation | 54 ± 11 | 46 ± 7 | 0.000 |

| 30 min after operation | 44 ± 6 | 44 ± 6 | 0.54 |

| 60 min after operation | 46 ± 9 | 43 ± 7 | 0.76 |

| pH, mean ± SD | |||

| At the end of operation | 7.33 ± 0.07 | 7.38 ± 0.05 | 0.001 |

| 30 min after operation | 7.40 ± 0.05 | 7.39 ± 0.05 | 0.63 |

| 60 min after operation | 7.39 ± 0.05 | 7.40 ± 0.06 | 0.71 |

| Arterial blood gas analysis . | LA . | GA . | P-Valuew . |

|---|---|---|---|

| pO2, mean ± SD | |||

| At the end of operation | 104 ± 50 | 173 ± 116 | 0.02 |

| 30 min after operation | 92 ± 26 | 89 ± 32 | 0.34 |

| 60 min after operation | 93 ± 25 | 89 ± 24 | 0.18 |

| pCO2, mean ± SD | |||

| At the end of operation | 54 ± 11 | 46 ± 7 | 0.000 |

| 30 min after operation | 44 ± 6 | 44 ± 6 | 0.54 |

| 60 min after operation | 46 ± 9 | 43 ± 7 | 0.76 |

| pH, mean ± SD | |||

| At the end of operation | 7.33 ± 0.07 | 7.38 ± 0.05 | 0.001 |

| 30 min after operation | 7.40 ± 0.05 | 7.39 ± 0.05 | 0.63 |

| 60 min after operation | 7.39 ± 0.05 | 7.40 ± 0.06 | 0.71 |

w: Wilcox–Mann–Whitney U-test.

GA: general anaesthesia; LA: local anaesthesia; SD: standard deviation.

Bold values represent statistical significance.

| Arterial blood gas analysis . | LA . | GA . | P-Valuew . |

|---|---|---|---|

| pO2, mean ± SD | |||

| At the end of operation | 104 ± 50 | 173 ± 116 | 0.02 |

| 30 min after operation | 92 ± 26 | 89 ± 32 | 0.34 |

| 60 min after operation | 93 ± 25 | 89 ± 24 | 0.18 |

| pCO2, mean ± SD | |||

| At the end of operation | 54 ± 11 | 46 ± 7 | 0.000 |

| 30 min after operation | 44 ± 6 | 44 ± 6 | 0.54 |

| 60 min after operation | 46 ± 9 | 43 ± 7 | 0.76 |

| pH, mean ± SD | |||

| At the end of operation | 7.33 ± 0.07 | 7.38 ± 0.05 | 0.001 |

| 30 min after operation | 7.40 ± 0.05 | 7.39 ± 0.05 | 0.63 |

| 60 min after operation | 7.39 ± 0.05 | 7.40 ± 0.06 | 0.71 |

| Arterial blood gas analysis . | LA . | GA . | P-Valuew . |

|---|---|---|---|

| pO2, mean ± SD | |||

| At the end of operation | 104 ± 50 | 173 ± 116 | 0.02 |

| 30 min after operation | 92 ± 26 | 89 ± 32 | 0.34 |

| 60 min after operation | 93 ± 25 | 89 ± 24 | 0.18 |

| pCO2, mean ± SD | |||

| At the end of operation | 54 ± 11 | 46 ± 7 | 0.000 |

| 30 min after operation | 44 ± 6 | 44 ± 6 | 0.54 |

| 60 min after operation | 46 ± 9 | 43 ± 7 | 0.76 |

| pH, mean ± SD | |||

| At the end of operation | 7.33 ± 0.07 | 7.38 ± 0.05 | 0.001 |

| 30 min after operation | 7.40 ± 0.05 | 7.39 ± 0.05 | 0.63 |

| 60 min after operation | 7.39 ± 0.05 | 7.40 ± 0.06 | 0.71 |

w: Wilcox–Mann–Whitney U-test.

GA: general anaesthesia; LA: local anaesthesia; SD: standard deviation.

Bold values represent statistical significance.

Of 18 patients in the preference arm, 17 chose LA. They exhibited decently higher satisfaction scores than the randomized LA patients, again not significantly different to the randomized GA group (Table 3). As only 1 patient of the preference arm chose GA, a statistical analysis of preference GA was not possible.

DISCUSSION

There have been a few trials comparing anaesthesia-related satisfaction in surgical procedures at least as secondary outcome, mostly in smaller outpatient obstetric procedures [19, 20] and inguinal hernia repair. Most trials did not investigate satisfaction in an appropriate manner. A recent RCT compared outpatient inguinal hernia repair in LA with and without conscious sedation using the Iowa Satisfaction with Anaesthesia Score, revealing higher satisfaction in LA with conscious sedation [21]. One RCT compared inguinal hernia repair in LA, regional anaesthesia and GA, but satisfaction was not assessed reliably [22]. A prospective non-randomized trial compared inguinal hernia repair in LA and GA using the same questionnaire as in our trial, revealing no statistical difference [23]. However, preference-based designs could be biased as patients tend to be more satisfied with their own decisions. Our data showed a slight, non-significant tendency of higher satisfaction in the preference LA group compared to the randomized LA group. We were also surprised to see that most patients of the preference arm chose LA, demonstrating the interest in and demand for LA in thoracic surgery, once the patients are explained and offered both types of anaesthesia. As in most cases in surgery, patients are not equally involved in choosing anaesthesia; this result may be of interest for other surgical disciplines, too.

Patients often are less afraid of the surgery itself but the narcosis; some are more anxious by the loss of control during general anaesthesia, while others are more afraid of awareness or pain during LA. So far, the patients’ feelings had not been subject to randomized controlled trials. While we failed to show superiority of LA over GA in terms of anaesthesia-related satisfaction, a potentially undetected but statistically significant difference (type II error) would not translate into a clinically significant difference, based on the assumptions in the study protocol. The real-life consequence is that we now can assure patients in our consultation hours that they do not need to be afraid of either type of anaesthesia, based on controlled data rather than personal experience.

In most secondary end points, LA was equal to GA, but LA patients were discharged significantly faster. The long chest tube time is explained by the patients who received permanent catheters for pleural carcinosis, which were removed a few weeks after surgery. As the proportion of these catheters was equal in both groups, the shorter length of stay in the LA group indicates a faster recovery. The reader has to note that in the German diagnosis-related group-based healthcare system with a mandatory minimum length of stay, this long length of stay is usual even for small procedures.

The discomfort both surgeons and anaesthesiologists felt with LA patients should not prevent them from operating in LA. Nowadays, the doctors are simply not used to operate on awake or mildly sedated patients and have to re-learn these skills. Habituation will probably increase the doctors’ satisfaction as well. However, this hypothesis cannot be examined in detail with our study setting.

Our study suffers from selection bias since the surgeons decided individually on whether a patient was technically suitable for surgery in LA; thus, personal preferences or skills in NiVATS would have influenced patient inclusion. Nonetheless, about one-third of operations were wedge resections in both groups, which shows that not only very simple pleural procedures were conducted. More complicated operations that require a deeper sedation, peridural catheter or upper airway supplies, which—from a patient’s perspective—are quite similar to GA, were excluded to better discriminate between GA and LA.

Furthermore, patients who would have benefitted the most from LA, i.e. elderly patients with a higher risk for delirium or postoperative neurocognitive impairments, could not participate because they were not able to answer the rather long questionnaires. Correspondingly, the delirium rate of 2% was much lower than usual (about 20% in general surgery [24]). Thus, we can only assume their satisfaction from the cognitive capable participants.

One strength of PASSAT trial is the use of valid instruments to measure anaesthesia-related patients’ satisfaction, which—we emphasize—is different from quality of life measurements [25, 26]. Quality of life aims to the mid- and long-term impact of a disease on the patient’s life; thus, there are influencing factors like economic aspects, family support, age, severity of disease, diagnosis and prognosis, which are not part of anaesthesia-related satisfaction. To our knowledge, the combination of a randomized and strict study design with valid instruments is unique, leading us to the assumption that patients should be actively offered LA if medically appropriate.

Of course, there are contraindications to both types of anaesthesia—which have been respected in the study—and the surgeons’ personal skills in NiVATS will limit the patient population considered for LA. Treating a conscious patient is more demanding for anaesthesiologists as well as surgeons, as seen by our survey of the treating physicians who felt more comfortable with the patient being in GA. Generally speaking, everybody from the anaesthesiologic unit, operation room and postanaesthesia care unit has to pay more attention to conscious patients. Silence in the operation room, warmed up skin disinfectant and headphones for the patients can help to let them feel more comfortable. As we had a learning curve, we assume that our patients could have had even higher satisfaction scores if we had these inconspicuous little improvements from the beginning. Furthermore, convincing patients to be randomly allocated to LA or GA was a tough task. Offering both types of anaesthesia during the premedication hours as part of a shared decision-making will strengthen the patient’s confidence, decrease their fears and accelerate their recovery, as seen in our trial, too.

CONCLUSION

Patients with minor VATS experience the same grade of anaesthesia-related satisfaction with both LA and GA. In our collective, patients with free choice mainly selected LA. Considering the known physiological advantages of LA, in combination with equal satisfaction, there is a further reason to actively offer LA to VATS patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Aldi Kraja for statistical advice.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All relevant data are within the article. The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Thomas Galetin: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Validation; Writing—original draft. Christoph Eckermann: Investigation; Resources; Writing—review & editing. Jerome M. Defosse: Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing—review & editing. Olger Kraja: Investigation; Writing—review & editing. Alberto Lopez-Pastorini: Investigation; Writing—review & editing. Julika Merres: Investigation; Software; Visualization; Writing—review & editing. Aris Koryllos: Investigation; Validation; Writing—review & editing. Erich Stoelben: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Writing—review & editing.

Reviewer information

European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery thanks Amit Bhargava, Madhuri Rao and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review process of this article.

REFERENCES

ABBREVIATIONS

- GA

General anaesthesia

- LA

Local anaesthesia

- OLV

One-lung ventilation

- SESOI

Smallest Effect Size of Interest

- VATS

Video-assisted thoracoscopy