-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Atsushi Kamigaichi, Keiju Aokage, Takashi Ikeno, Masashi Wakabayashi, Tomohiro Miyoshi, Kenta Tane, Joji Samejima, Masahiro Tsuboi, Long-term survival outcomes after lobe-specific nodal dissection in patients with early non-small-cell lung cancer, European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Volume 63, Issue 2, February 2023, ezad016, https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezad016

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We investigated the long-term outcomes of lobe-specific nodal dissection (LSD) and systematic nodal dissection (SND) in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Patients with c-stage I and II NSCLC who underwent lobectomy with mediastinal nodal dissection were retrospectively analysed. After propensity score matching, we assessed the overall survival (OS), recurrence-free survival (RFS) and cumulative incidence of death (CID) from primary lung cancer and other diseases.

The median follow-up period was 8.4 years. Among 438 propensity score-matched pairs, OS and RFS were similar between the LSD and SND groups [hazard ratio (HR), 0.979; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.799–1.199; and HR, 0.912; 95% CI, 0.762–1.092, respectively], but the LSD group showed a better prognosis after 5 years postoperatively. CID from primary lung cancer was similar between the 2 groups (HR, 1.239; 95% CI, 0.940–1.633). However, the CID from other diseases was lower in the LSD group than in the SND group (HR, 0.702; 95% CI, 0.525–0.938). According to c-stage, the LSD group tended towards worse OS and RFS, with higher CID from primary lung cancer than the SND group, in patients with c-stage II.

LSD provides acceptable long-term survival for patients with early-stage NSCLC. However, LSD may not be suitable for patients with c-stage II NSCLC due to the higher mortality risk from primary lung cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, and its incidence has increased over the past 2 decades [1]. Since the proposal of ‘radical lobectomy’ by Cahan in 1960, the standard surgical procedure for non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been lobectomy with hilar and mediastinal lymph node (LN) dissection [2]. Moreover, since the proposal of the LN map, systematic nodal dissection (SND) has been performed globally during surgery for NSCLC [3, 4]. However, in 2011, the American College of Surgery Oncology Group (ACSOG Z0030) trial, a large-scale multi-institutional randomized clinical trial (RCT) comparing mediastinal SND versus systematic nodal sampling (SS), showed that SND did not provide a survival benefit compared to SS. The therapeutic significance of SND was not evident [5]. Based on this, SS is widely performed for early-stage lung cancer in current clinical practice [6].

However, since several studies revealed characteristic nodal metastatic patterns according to each lung lobe [7], lobe-specific nodal dissection (LSD) has been proposed, which omits dissection of mediastinal regions with a low risk of metastasis, according to each lung lobe. LSD has been performed for early-stage NSCLC instead of SND in several regions, and previous studies have reported that LSD has survival and recurrence rates similar to SND [8–14].

Recently, the long-term survival outcomes after surgery for early-stage NSCLC have gained attention with increasing detection of early-stage NSCLC due to the development of imaging modalities. However, there are no reports on long-term outcomes beyond 5 years after LSD, and the prognostic impact of the extent of LN dissection in the late postoperative period has not been sufficiently assessed. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the survival outcomes of LSD and SND during long-term follow-up in patients with early-stage NSCLC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical statement

This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and national research committees and the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. This study was conducted under the waiver of authorization approved by the National Cancer Center East institutional review board (no. 2017-418) in March 2018. The requirement for informed consent from individual patients was waived owing to the retrospective design of this study.

Patient population

Prospectively collected medical records from patients with clinical stage IA–IIB NSCLC, who underwent curative surgery by lobectomy without induction therapy at the National Cancer Center Hospital East between January 2006 and December 2014, were reviewed in this study. Patients who underwent only dissection of hilar LNs (ND1a or ND1b) and with right middle lobe or synchronous lung cancer were excluded (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). Histological type, pathological tumour size and invasive component size were reviewed according to the 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus, and Heart [15]. Tumour staging was based on the eighth edition of the TNM classification of the Union for International Cancer Control [16].

Preoperative staging

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scans at 5- to 10-mm collimation of the chest and upper abdomen were obtained to assess the clinical staging of all patients with lung cancer. Moreover, thin-section CT images at 1- to 2-mm collimation were reconstructed to evaluate primary tumour size, ground-glass opacity (GGO) component, solid size and other factors. Clinical LN staging was performed by preoperative contrast CT and 18 fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT. Any mediastinal LN of >1.0 cm in the shortest dimension on thin-slice CT and/or showing an abnormal uptake of 18 fluoro-2-deoxyglucose on 18 fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT was defined as a node-positive tumour. If required, we performed endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration cytology for N staging and for determining indication for surgery.

Surgical procedure

All patients underwent lobectomy involving dissection of the hilar and mediastinal LNs (ND2a). LNs were resected en bloc as a lump with the surrounding fatty tissue. Participants were classified into LSD and SND groups according to the extent of LN dissection. The types of procedures were primarily decided on the basis of surgeon preference. Supplementary Material, Table S1 presents the extent of mediastinal nodal dissection during SND and LSD. The SND group underwent systematic mediastinal nodal dissection (#2R, 4R, 7, 8 and 9 for right-sided tumours and #4L, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 for left-sided tumours). LSD was performed based on nodal metastasis patterns. During the resection of a tumour located in the right upper lobe, upper mediastinal LNs, including the right upper and lower paratracheal nodes (#2R, 4R), were dissected. When we resected cancer located in the left upper lobe, left upper paratracheal (#4L) and aortic nodes in the anteroposterior zone (#5, 6) were dissected. When the tumour was located in the lower lobe, lower mediastinal (#8, 9) and subcarinal (#7) LNs were dissected. N1 nodes, including hilar (#10), interlobar zone (#11) and peripheral zone (#12–14) nodes, were routinely resected wherever cancer was detected. Any suspicious LNs were biopsied and assessed intraoperatively using frozen sections.

Patient follow-up

We examined patients at 3- to 6-month intervals for the first 2 years, at 6- to 12-month intervals for the next 3 years and then at 1-year intervals thereafter. All patients were followed up for at least 5 years and up to 10 years after surgery. Recurrence was diagnosed based on physical examination and/or imaging findings, and the diagnosis was histologically confirmed when clinically feasible.

Statistical analyses

Patient characteristics are summarized using proportions or descriptive statistics, such as the median and interquartile range. Chi-squared and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were performed to compare the LSD and SND groups, and propensity score matching was conducted to balance potential differences in the baseline characteristics between groups. The propensity score was estimated using a logistic regression model, without looking at the outcome information of survival, based on preoperative characteristics, including age (continuous), sex (female/male), smoking history (never/ever), history of other cancers (absent/present), cardiovascular disease (absent/present), diabetes mellitus (absent/present), preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level, GGO (absent/present), radiological invasive tumour size (continuous), clinical stage (IA/IB/II), tumour location (upper lobe/lower lobe), side (right/left) and histology (adenocarcinoma/squamous cell carcinoma/others) as explanatory variables. Greedy matching with a calliper width of 0.20 of the standard deviation of the logit transformation for the estimated propensity score was applied [17]. Propensity score matching at a 1:1 ratio was performed using the estimated propensity score. To evaluate the estimated propensity score, histograms and box plots were created, and standardized differences were calculated to investigate the balance of patient characteristics. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from surgery to death from any cause or was censored at the last follow-up. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was defined as the time from surgery to recurrence or death from any cause or was censored at the last follow-up. Survival data were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the hazard ratio (HR) and its confidence interval (CI) based on robust variance were estimated by the Cox proportional hazards model in the comparisons between groups. A landmark analysis at 5 years was also utilized to assess the impact of the extent of nodal dissection on survival in the late period after surgery. Restricted mean survival time from 0 to 5 and 10 years were also estimated, and the test statistics of their difference between groups were based on an asymptotic normal distribution. Time-to-event end points were also analysed in consideration of competing risks. The risk of death from primary lung cancer, defined as the cumulative incidence of death (CID) from primary lung cancer, was estimated using a cumulative incidence function, which accounted for other causes of death as a competing risk. Similarly, the risk of death from other diseases, defined as the CID from other diseases, was estimated using a cumulative incidence function, which accounted for death from primary lung cancer as a competing risk. Other diseases included cancers other than primary NSCLC and non-malignant diseases. Differences in CID from primary lung cancer and other diseases between groups were assessed using Gray’s test and the Fine–Gray model.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant, without adjustment for multiple testing.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics and prognosis of the lobe-specific nodal dissection and systematic nodal dissection groups in all cohorts

A total of 1453 patients were included in this study. Supplementary Material, Table S2 shows the patient characteristics of the LSD (n = 502) and SND (n = 951) groups. Significant differences were found between these groups in clinical characteristics, such as age (P < 0.001), history of cancers other than primary NSCLC (P = 0.0022), location (P < 0.001), carcinoembryonic antigen level (P = 0.023), GGO presence (P < 0.001), radiological invasive tumour size (P < 0.001), consolidation to maximum tumour ratio (P = 0.034), clinical stage (P < 0.001) and histology (P = 0.0012). In the SND group, skipped nodal metastasis to the upper mediastinal region in lower lobe lung cancer was observed in 1 (0.2%) patient. In addition, skipped nodal metastasis to the subcarinal and lower mediastinal regions in upper lobe lung cancer was observed in 1 (0.2%) patient.

The median follow-up duration was 8.4 (interquartile range, 7.0–10.0) years. OS and RFS were significantly better in the LSD group than in the SND group [HR, 0.714; 95% CI, 0.579–0.882 (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2A) and HR, 0.692; 95% CI, 0.575–0.835 (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2B), respectively].

Patient characteristics and prognosis of the lobe-specific nodal dissection and systematic nodal dissection groups in propensity score-matched pairs

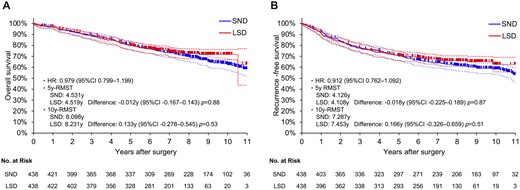

The characteristics of propensity score-matched pairs are shown in Table 1. All clinical variables were balanced between the groups. The details of postoperative complications are shown in Supplementary Material, Table S3. The arrhythmias occurred more frequently in the SND group than in the LSD group (P = 0.038). In addition, similar OS and RFS stratified by matched pairs were found between the LSD and SND groups [HR, 0.979; 95% CI, 0.799–1.199 (Fig. 1A); and HR, 0.912; 95% CI, 0.762–1.092 (Fig. 1B), respectively]. OS and RFS that were not stratified by matched pairs also showed similar results (HR, 0.876; 95% CI, 0.685–1.121; and HR, 0.888; 95% CI, 0.712–1.107, respectively). Meanwhile, in the landmark analysis, the LSD group showed significantly better OS (HR, 0.616; 95% CI, 0.389–0.974) and RFS (HR, 0.544; 95% CI, 0.317–0.932) after 5 years postoperatively (figure not shown).

OS and RFS curves of patients who underwent LSD or SND in propensity score-matched cohorts (A, OS; B, RFS). CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; LSD: lobe-specific nodal dissection; OS: overall survival; RFS: recurrence-free survival; RMST: restricted mean survival time; SND: systematic nodal dissection.

| Variables . | Group . | P-Value . | Standardized difference . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSD (n = 438) . | SND (n = 438) . | |||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 69 (62–74) | 69 (63–75) | 0.48 | 0.045 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 276 (63.0) | 283 (64.6) | 0.62 | 0.033 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 289 (66.0) | 292 (66.7) | 0.83 | 0.014 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Other cancers | 77 (17.6) | 74 (16.9) | 0.79 | 0.018 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 37 (8.5) | 37 (8.5) | 1.0 | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 66 (15.1) | 66 (15.1) | 1.0 | 0 |

| Severe COPD | 2 (0.5) | 4 (0.9) | 0.41 | 0.055 |

| Nodule location, n (%) | ||||

| Right upper lobe | 169 (38.6) | 186 (42.5) | ||

| Right lower lobe | 91 (20.8) | 70 (16.0) | ||

| Left upper lobe | 137 (31.3) | 118 (26.9) | ||

| Left lower lobe | 41 (9.4) | 64 (124.6) | ||

| Upper lobe | 306 (69.9) | 304 (69.4) | 0.88 | 0.010 |

| Lower lobe | 132 (30.1) | 134 (30.6) | ||

| Right side | 260 (59.4) | 256 (58.5) | 0.78 | 0.019 |

| Left side | 178 (40.6) | 182 (41.6) | ||

| CEA, n (%) | ||||

| ≥5 ng/ml | 106 (24.2) | 113 (25.8) | 0.59 | 0.037 |

| Solid tumour size on CT (cm), median (IQR) | 2.2 (1.5–3.0) | 2.3 (1.5–3.0) | 0.38 | 0.051 |

| The presence of GGO component, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 194 (44.3) | 187 (42.7) | 0.63 | 0.037 |

| C/T ratio, median (IQR) | 1 (0.8–1) | 1 (0.7–1) | 0.26 | 0.086 |

| Clinical stage, n (%) | 0.65 | 0.073 | ||

| Stage IA | 325 (74.2) | 325 (74.2) | ||

| Stage IB | 54 (12.3) | 47 (10.7) | ||

| Stage II | 59 (13.5) | 66 (15.1) | ||

| Clinical pulmonary metastasis, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) | 0.32 | 0.068 |

| Clinical pleural invasion, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 19 (2.5) | 6 (0.8) | 0.011 | 0.173 |

| Histological type, n (%) | 0.57 | 0.082 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 334 (76.3) | 331 (75.6) | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 70 (16.0) | 79 (18.0) | ||

| Others | 34 (7.8) | 28 (6.4) | ||

| Pathological solid tumour size (cm), median (IQR) | 1.7 (1.0–2.5) | 1.9 (1.2–2.8) | 0.018 | |

| Pathological stage, n (%) | 0.33 | |||

| Stage 0 | 9 (2.1) | 7 (1.6) | ||

| Stage IA | 266 (60.7) | 279 (63.7) | ||

| Stage IB | 72 (16.4) | 64 (14.6) | ||

| Stage IIA | 9 (2.1) | 13 (3.0) | ||

| Stage IIB | 51 (11.6) | 52 (11.9) | ||

| Stage IIIA | 30 (6.9) | 38 (8.7) | ||

| Stage IIIB | 1 (0.2) | 5 (1.1) | ||

| Variables . | Group . | P-Value . | Standardized difference . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSD (n = 438) . | SND (n = 438) . | |||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 69 (62–74) | 69 (63–75) | 0.48 | 0.045 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 276 (63.0) | 283 (64.6) | 0.62 | 0.033 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 289 (66.0) | 292 (66.7) | 0.83 | 0.014 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Other cancers | 77 (17.6) | 74 (16.9) | 0.79 | 0.018 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 37 (8.5) | 37 (8.5) | 1.0 | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 66 (15.1) | 66 (15.1) | 1.0 | 0 |

| Severe COPD | 2 (0.5) | 4 (0.9) | 0.41 | 0.055 |

| Nodule location, n (%) | ||||

| Right upper lobe | 169 (38.6) | 186 (42.5) | ||

| Right lower lobe | 91 (20.8) | 70 (16.0) | ||

| Left upper lobe | 137 (31.3) | 118 (26.9) | ||

| Left lower lobe | 41 (9.4) | 64 (124.6) | ||

| Upper lobe | 306 (69.9) | 304 (69.4) | 0.88 | 0.010 |

| Lower lobe | 132 (30.1) | 134 (30.6) | ||

| Right side | 260 (59.4) | 256 (58.5) | 0.78 | 0.019 |

| Left side | 178 (40.6) | 182 (41.6) | ||

| CEA, n (%) | ||||

| ≥5 ng/ml | 106 (24.2) | 113 (25.8) | 0.59 | 0.037 |

| Solid tumour size on CT (cm), median (IQR) | 2.2 (1.5–3.0) | 2.3 (1.5–3.0) | 0.38 | 0.051 |

| The presence of GGO component, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 194 (44.3) | 187 (42.7) | 0.63 | 0.037 |

| C/T ratio, median (IQR) | 1 (0.8–1) | 1 (0.7–1) | 0.26 | 0.086 |

| Clinical stage, n (%) | 0.65 | 0.073 | ||

| Stage IA | 325 (74.2) | 325 (74.2) | ||

| Stage IB | 54 (12.3) | 47 (10.7) | ||

| Stage II | 59 (13.5) | 66 (15.1) | ||

| Clinical pulmonary metastasis, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) | 0.32 | 0.068 |

| Clinical pleural invasion, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 19 (2.5) | 6 (0.8) | 0.011 | 0.173 |

| Histological type, n (%) | 0.57 | 0.082 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 334 (76.3) | 331 (75.6) | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 70 (16.0) | 79 (18.0) | ||

| Others | 34 (7.8) | 28 (6.4) | ||

| Pathological solid tumour size (cm), median (IQR) | 1.7 (1.0–2.5) | 1.9 (1.2–2.8) | 0.018 | |

| Pathological stage, n (%) | 0.33 | |||

| Stage 0 | 9 (2.1) | 7 (1.6) | ||

| Stage IA | 266 (60.7) | 279 (63.7) | ||

| Stage IB | 72 (16.4) | 64 (14.6) | ||

| Stage IIA | 9 (2.1) | 13 (3.0) | ||

| Stage IIB | 51 (11.6) | 52 (11.9) | ||

| Stage IIIA | 30 (6.9) | 38 (8.7) | ||

| Stage IIIB | 1 (0.2) | 5 (1.1) | ||

C/T ratio, consolidation–tumour ratio; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CT, computed tomography; GGO, ground-glass opacity; IQR, interquartile range; LSD, lobe-specific nodal dissection; SND, systematic nodal dissection.

| Variables . | Group . | P-Value . | Standardized difference . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSD (n = 438) . | SND (n = 438) . | |||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 69 (62–74) | 69 (63–75) | 0.48 | 0.045 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 276 (63.0) | 283 (64.6) | 0.62 | 0.033 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 289 (66.0) | 292 (66.7) | 0.83 | 0.014 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Other cancers | 77 (17.6) | 74 (16.9) | 0.79 | 0.018 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 37 (8.5) | 37 (8.5) | 1.0 | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 66 (15.1) | 66 (15.1) | 1.0 | 0 |

| Severe COPD | 2 (0.5) | 4 (0.9) | 0.41 | 0.055 |

| Nodule location, n (%) | ||||

| Right upper lobe | 169 (38.6) | 186 (42.5) | ||

| Right lower lobe | 91 (20.8) | 70 (16.0) | ||

| Left upper lobe | 137 (31.3) | 118 (26.9) | ||

| Left lower lobe | 41 (9.4) | 64 (124.6) | ||

| Upper lobe | 306 (69.9) | 304 (69.4) | 0.88 | 0.010 |

| Lower lobe | 132 (30.1) | 134 (30.6) | ||

| Right side | 260 (59.4) | 256 (58.5) | 0.78 | 0.019 |

| Left side | 178 (40.6) | 182 (41.6) | ||

| CEA, n (%) | ||||

| ≥5 ng/ml | 106 (24.2) | 113 (25.8) | 0.59 | 0.037 |

| Solid tumour size on CT (cm), median (IQR) | 2.2 (1.5–3.0) | 2.3 (1.5–3.0) | 0.38 | 0.051 |

| The presence of GGO component, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 194 (44.3) | 187 (42.7) | 0.63 | 0.037 |

| C/T ratio, median (IQR) | 1 (0.8–1) | 1 (0.7–1) | 0.26 | 0.086 |

| Clinical stage, n (%) | 0.65 | 0.073 | ||

| Stage IA | 325 (74.2) | 325 (74.2) | ||

| Stage IB | 54 (12.3) | 47 (10.7) | ||

| Stage II | 59 (13.5) | 66 (15.1) | ||

| Clinical pulmonary metastasis, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) | 0.32 | 0.068 |

| Clinical pleural invasion, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 19 (2.5) | 6 (0.8) | 0.011 | 0.173 |

| Histological type, n (%) | 0.57 | 0.082 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 334 (76.3) | 331 (75.6) | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 70 (16.0) | 79 (18.0) | ||

| Others | 34 (7.8) | 28 (6.4) | ||

| Pathological solid tumour size (cm), median (IQR) | 1.7 (1.0–2.5) | 1.9 (1.2–2.8) | 0.018 | |

| Pathological stage, n (%) | 0.33 | |||

| Stage 0 | 9 (2.1) | 7 (1.6) | ||

| Stage IA | 266 (60.7) | 279 (63.7) | ||

| Stage IB | 72 (16.4) | 64 (14.6) | ||

| Stage IIA | 9 (2.1) | 13 (3.0) | ||

| Stage IIB | 51 (11.6) | 52 (11.9) | ||

| Stage IIIA | 30 (6.9) | 38 (8.7) | ||

| Stage IIIB | 1 (0.2) | 5 (1.1) | ||

| Variables . | Group . | P-Value . | Standardized difference . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSD (n = 438) . | SND (n = 438) . | |||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 69 (62–74) | 69 (63–75) | 0.48 | 0.045 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 276 (63.0) | 283 (64.6) | 0.62 | 0.033 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 289 (66.0) | 292 (66.7) | 0.83 | 0.014 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Other cancers | 77 (17.6) | 74 (16.9) | 0.79 | 0.018 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 37 (8.5) | 37 (8.5) | 1.0 | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 66 (15.1) | 66 (15.1) | 1.0 | 0 |

| Severe COPD | 2 (0.5) | 4 (0.9) | 0.41 | 0.055 |

| Nodule location, n (%) | ||||

| Right upper lobe | 169 (38.6) | 186 (42.5) | ||

| Right lower lobe | 91 (20.8) | 70 (16.0) | ||

| Left upper lobe | 137 (31.3) | 118 (26.9) | ||

| Left lower lobe | 41 (9.4) | 64 (124.6) | ||

| Upper lobe | 306 (69.9) | 304 (69.4) | 0.88 | 0.010 |

| Lower lobe | 132 (30.1) | 134 (30.6) | ||

| Right side | 260 (59.4) | 256 (58.5) | 0.78 | 0.019 |

| Left side | 178 (40.6) | 182 (41.6) | ||

| CEA, n (%) | ||||

| ≥5 ng/ml | 106 (24.2) | 113 (25.8) | 0.59 | 0.037 |

| Solid tumour size on CT (cm), median (IQR) | 2.2 (1.5–3.0) | 2.3 (1.5–3.0) | 0.38 | 0.051 |

| The presence of GGO component, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 194 (44.3) | 187 (42.7) | 0.63 | 0.037 |

| C/T ratio, median (IQR) | 1 (0.8–1) | 1 (0.7–1) | 0.26 | 0.086 |

| Clinical stage, n (%) | 0.65 | 0.073 | ||

| Stage IA | 325 (74.2) | 325 (74.2) | ||

| Stage IB | 54 (12.3) | 47 (10.7) | ||

| Stage II | 59 (13.5) | 66 (15.1) | ||

| Clinical pulmonary metastasis, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) | 0.32 | 0.068 |

| Clinical pleural invasion, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 19 (2.5) | 6 (0.8) | 0.011 | 0.173 |

| Histological type, n (%) | 0.57 | 0.082 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 334 (76.3) | 331 (75.6) | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 70 (16.0) | 79 (18.0) | ||

| Others | 34 (7.8) | 28 (6.4) | ||

| Pathological solid tumour size (cm), median (IQR) | 1.7 (1.0–2.5) | 1.9 (1.2–2.8) | 0.018 | |

| Pathological stage, n (%) | 0.33 | |||

| Stage 0 | 9 (2.1) | 7 (1.6) | ||

| Stage IA | 266 (60.7) | 279 (63.7) | ||

| Stage IB | 72 (16.4) | 64 (14.6) | ||

| Stage IIA | 9 (2.1) | 13 (3.0) | ||

| Stage IIB | 51 (11.6) | 52 (11.9) | ||

| Stage IIIA | 30 (6.9) | 38 (8.7) | ||

| Stage IIIB | 1 (0.2) | 5 (1.1) | ||

C/T ratio, consolidation–tumour ratio; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CT, computed tomography; GGO, ground-glass opacity; IQR, interquartile range; LSD, lobe-specific nodal dissection; SND, systematic nodal dissection.

Figures 2 and 3 show OS and RFS according to the clinical stage. Among patients with clinical stages IA and IB, OS and RFS were similar between groups. Conversely, among patients with clinical stage II, OS and RFS tended to be worse in the LSD group (HR, 1.376; 95% CI, 0.834–2.270 and HR, 1.287; 95% CI, 0.833–1.990, respectively) throughout the entire period, albeit not significantly. In patients with pathological stages IA and IB NSCLC, OS and RFS were similar between groups (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3).

![OS curves of the LSD and SND groups at each clinical stage in propensity score-matched cohorts [(A) clinical stage IA; (B) clinical stage IB; and (C) clinical stage II]. CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; LSD: lobe-specific nodal dissection; NSCLC: non-small-cell lung cancer; OS: overall survival; RMST: restricted mean survival time; SND: systematic nodal dissection.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ejcts/63/2/10.1093_ejcts_ezad016/1/m_ezad016f2.jpeg?Expires=1747891235&Signature=oQ9QwYHlIhlxwRsPk-sdj8IotKkT35huRYlTlqFZlXp2a8gpv0rb11Ki693ZOLUXR8c0~nolebsmF9WXMSngbQ7x6GradSW84B-BeI6gUcVGIKw4VY-jVuI8m6nOJoYp64YNWZiTIr8-yBJA1Ufrz2-M9qVLYebXxtALOdcMq89Slwy679wCe3CnXCN3-kUgweyFGZATXhMqi03xkvS26qQCXMzYbXMx9uFI7A69PX77XvjU2wW8I-ixQrVFqJK4Ur3MDMZ6BO8LEOxVaCqLriNCTybYt7L9FWbEZwj~UvtderVibOrw0OJVdGTbhlaOhKCKSOn58yn9ANosbKTCeg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

OS curves of the LSD and SND groups at each clinical stage in propensity score-matched cohorts [(A) clinical stage IA; (B) clinical stage IB; and (C) clinical stage II]. CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; LSD: lobe-specific nodal dissection; NSCLC: non-small-cell lung cancer; OS: overall survival; RMST: restricted mean survival time; SND: systematic nodal dissection.

![RFS curves of the LSD and SND groups at each clinical stage in propensity score-matched cohorts [(A) clinical stage IA; (B) clinical stage IB; and (C) clinical stage II]. CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; LSD: lobe-specific nodal dissection; NSCLC: non-small-cell lung cancer; RFS: recurrence-free survival; RMST: restricted mean survival time; SND: systematic nodal dissection.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ejcts/63/2/10.1093_ejcts_ezad016/1/m_ezad016f3.jpeg?Expires=1747891235&Signature=rGQHN9ijazg612MJnt2V93X8gTnzdQeURqINEiiChm0YLMpfYNEj~EpW4zWv~o4ex39h5poALTCs9Y2YcfjqFPX1Rv3ucyyZGQqiGxWEyuoYoslbc146pgGjfVaPcFNL9gTOFt4-wO6lF3DgxD43H1P028kJPcoOAwKtWaxNieF~H-AvdyAwU3X1pbU48uuPb4JiOrIm9Go7nS310jXbnGwAYsDIX7kDN7dnmO0W3hV0tn0NR498Hw9P77oy8jO8OblDcOgb-gwWKOqZQe8FBL1JVaQzSYWlzuyBTu2CmaB~LRJsXmJNmTDWPuNmuM0VDJDouK2Qb4M7RfiHiOvqsw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

RFS curves of the LSD and SND groups at each clinical stage in propensity score-matched cohorts [(A) clinical stage IA; (B) clinical stage IB; and (C) clinical stage II]. CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; LSD: lobe-specific nodal dissection; NSCLC: non-small-cell lung cancer; RFS: recurrence-free survival; RMST: restricted mean survival time; SND: systematic nodal dissection.

Supplementary Material, Figs. S4 and S5 show the OS and RFS, respectively, according to the lung lobe where the tumour was located. For each lung lobe, there were no significant differences in OS and RFS between the groups.

Supplementary Material, Tables S4 and S5 show the loco-regional and distant sites of the first relapse in patients with clinical stage I and II NSCLC, respectively. Among patients with clinical stage I NSCLC, loco-regional relapses occurred in 29 (7.7%) and 31 (8.3%) patients in the LSD and SND groups, respectively. Among patients with clinical stage II NSCLC, loco-regional relapses occurred in 17 (28.8%) and 6 (9.1%) patients in the LSD and SND groups, respectively.

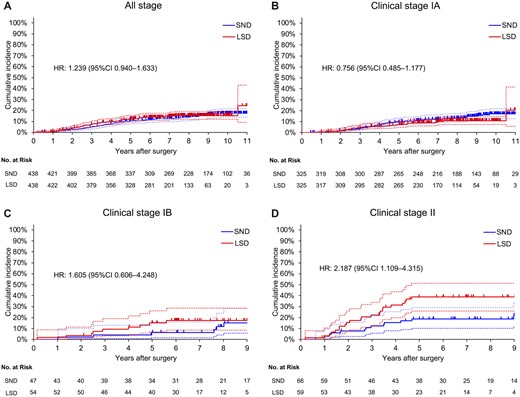

Cumulative incidence of death between the lobe-specific nodal dissection and systematic nodal dissection groups in propensity score-matched pairs

CID from primary lung cancer was similar between the LSD and SND groups (HR, 1.239; 95% CI, 0.940–1.633; Fig. 4A). According to the clinical stage, CID from primary lung cancer was similar between the groups among patients with clinical stages IA and IB (Fig. 4B and C). Conversely, among patients with clinical stage II, CID from primary lung cancer was higher in the LSD group than in the SND group (HR, 2.187; 95% CI, 1.109–4.315; Fig. 4D).

CID from primary lung cancer in the LSD and SND groups in propensity score-matched cohorts [(A) all stage; (B) clinical stage IA; (C) clinical stage IB; and (D) clinical stage II). CI: confidence interval; CID: cumulative incidence of death; HR: hazard ratio; LSD: lobe-specific nodal dissection; SND: systematic nodal dissection.

CID from other diseases was significantly lower in the LSD group than in the SND group (HR, 0.702; 95% CI, 0.525–0.938; Fig. 5A). For each clinical stage, the LSD group tended towards less CID from other diseases than the SND group, albeit non-significantly (Fig. 5B–D). Supplementary Material, Tables S6 and S7 show detailed causes of death due to other diseases in the LSD and SND groups before and after the postoperative 5-year period, respectively. Before 5 years postoperatively, death due to other diseases was comparable between the LSD (n = 33, 7.5%) and SND (n = 39, 8.9%) groups. In addition, after 5 years postoperatively, death due to other diseases occurred in 15 (3.4%) and 41 (9.4%) patients of the LSD and SND groups, respectively.

![CID from other diseases in the LSD and SND groups in propensity score-matched cohorts [(A) all stages; (B) clinical stage IA; (C) clinical stage IB; and (D) clinical stage II]. CI: confidence interval; CID: cumulative incidence of death; HR: hazard ratio; LSD: lobe-specific nodal dissection; SND: systematic nodal dissection](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ejcts/63/2/10.1093_ejcts_ezad016/1/m_ezad016f5.jpeg?Expires=1747891235&Signature=3oD~2qnoc6~in8N~9276mU7hlzDfozaWU7ZJ2SYe-Gn-ydyaVV7b6HRKpvK07ZiVxw8FD5aM1fWa6g7QsBk5IZwitgY9M7e73pVLVNm-mnBsqBdVy27bjAMsIdlVQ~yUg1FFUZdUZ4fyV8S8uqVDUpcnFkQw~krsArcJaV-~g7tkIMVswP56p8-d-ZEvSMePDCNz1-fBL52kXG92KhzUsenQKrPAY6i6HxqlwoQrwHv6pBZHTFWuC5gWC0hy7XKiliD6yyNLfvDWntXRHB59gFEfCnJgcngVUsdmgF2VK5eyo58nGL0R32Jw7cK87Y38xhQQ-2K5EWKvbnUl50DyiQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

CID from other diseases in the LSD and SND groups in propensity score-matched cohorts [(A) all stages; (B) clinical stage IA; (C) clinical stage IB; and (D) clinical stage II]. CI: confidence interval; CID: cumulative incidence of death; HR: hazard ratio; LSD: lobe-specific nodal dissection; SND: systematic nodal dissection

DISCUSSION

This study reported acceptable long-term outcomes after LSD compared to those for SND in patients with early-stage NSCLC. Although LSD showed similar long-term survival and provided a survival benefit in late postoperative period compared to SND, LSD was inferior to SND due to the higher risk of death from primary lung cancer in patients with clinical stage II NSCLC.

Regarding the operative procedure for LNs during surgery for NSCLC, SND was compared with nodal sampling in 3 RCTs between 1998 and 2002, with heterogeneous results [18–20]. Wu et al. [20] reported that SND could improve survival; however, no significant difference in the recurrence rate or survival was observed between SND and SS in the other 2 trials [18, 19]. Moreover, Wright et al. [21] reported that SND was associated with improved survival compared with node sampling in a meta-analysis of these RCTs. Furthermore, the ACSOG Z0030 trial showed that, although SND identified 4% of patients with positive nodes in the mediastinum that were missed by SS, there was no survival benefit for SND in patients with early-stage NSCLC [5]. Consequently, SS is widely performed for early-stage lung cancer in current clinical practice [6]. In several regions, mainly in Japan, LSD has been performed for early-stage NSCLC, instead of SND or SS, based on the characteristic patterns of nodal metastasis according to the primary tumour location. The extent of nodal dissection proposed by Cahan in 1960 was similar to the extent of today’s LSD [2]. Recently, LSD has been oncologically equivalent to SND, although the staging ability of LSD may not exceed that of SND or SS due to less exploration of mediastinal regions [8–14]. Based on the results of the present study, LSD can provide acceptable long-term survival compared to SND in patients with early-stage NSCLC. Although LSD may be especially disadvantageous in the case of skipped nodal metastasis beyond the lobe-specific region, such case was rare in the present study, which is consistent with the results of previous studies [7, 8]. Thus, LSD seems to be a feasible procedure in early-stage NSCLC. However, despite the equivalent long-term survival outcomes between LSD and SND, the risk of death from primary lung cancer was significantly higher in the LSD group than in the SND group among patients with clinical stage II NSCLC. Furthermore, relapse in the ipsilateral mediastinal LNs occurred more frequently in the LSD group among patients with clinical stage II NSCLC. The frequency of unsuspected pathological N2 disease is approximately 2.0–18.5% of all resectable NSCLCs, and the risk of unsuspected nodal metastasis increases with T-factor upstaging [22]. LSD may not adequately evaluate the mediastinal nodal staging for patients with clinical stage II NSCLC. Therefore, we recommend SND during surgery for such patients.

This study showed a survival advantage of LSD in death due to other diseases compared to SND. Extensive mediastinal lymph node dissection may result in the dissection of the pulmonary and cardiac branches of the vagus nerve because these branches run over the subcarinal and main bronchial LNs in a complex pattern [23]. The vagus nerve plays an important role in cardiopulmonary functions, such as mucus production, mucociliary clearance to inhaled irritants, bronchoconstriction, bronchial vasodilation, blood pressure and heart rate control and systemic and local inflammatory response regulation [24–26]. Although chronic cardiopulmonary dysfunction caused by dissection of the vagus nerve branch may be related to late death after 5 years postoperatively due to other diseases, further studies are required. An ongoing randomized phase III trial conducted by the Japanese Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG1413) aims to compare the surgical results between LSD and SND in patients with clinical stage I and II NSCLC [27]. The results of this prospective study may provide valuable insights into the survival benefit of LSD.

There are no established recommendations regarding the removal of particular stations during routine LSD. As reported in previous studies, only LNs in the upper mediastinum (#2R and #4R on the right side; #4L, 5 and 6 on the left side) are dissected for upper lobe tumours, and only LNs in the subcarina and lower mediastinum (#7, 8 and 9) are dissected for lower lobe tumours in Japan [8–10, 12, 13]. Conversely, according to the recommendations of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer and European Society of Thoracic Surgeons [28], dissection of LNs in the subcarina and upper mediastinum is required for tumours in the upper lobe during LSD. Moreover, according to the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons guidelines, LN dissection of #4R, as well as the lower mediastinum, is required for tumours in the right lower lobe [28]. In contrast, LN dissection of #4L is not required for tumours in the left upper lobe [28]. The establishment of standard procedures for LSD warrants further study.

Limitations

First, this was a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected patient data, thus resulting in limitations, including the inability to verify uniform consistency in operative techniques for the groups and specific information pertaining to the surgical approach used for the LN harvesting between surgeons and the way this is reported. Regarding the cause of death, details on other cancers and non-malignant diseases were not available in some cases. Furthermore, a multiple comparison problem exists in the subgroup analysis. A confirmatory trial is warranted in the future. Second, the indications for LSD or SND might not be equivalent, which might lead to a selection bias. We included more confounding variables than previous reports in the propensity score matching analysis; consequently, patient and oncological backgrounds were sufficiently matched. Third, planned LSD might have been converted to SND if LN metastasis was suspected or diagnosed intraoperatively. However, there are no data on the number of such cases. This indicates that the SND group may have had inherently higher tumour malignancy than the LSD group. Fourth, in Japan, SS is not performed in daily clinical practice, and we could not compare the survival outcomes between LSD and SS.

CONCLUSION

LSD can provide acceptable long-term survival with a survival benefit in late postoperative period in patients with early-stage NSCLC. However, SND may be suitable for patients with clinical stage II NSCLC due to the higher risk of death from primary NSCLC in LSD.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at EJCTS online.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Editage (www.editage.com) for the English language review.

Funding

This study received no funding support.

Conflict of interest: Masahiro Tsuboi reports grants from Boehringer-Ingelheim Japan, MSD, AstraZeneca KK, Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Bristol-Myers Squibb KK, Novartis and Eli Lilly Japan and personal fees from Johnson & Johnson Japan, AstraZeneca KK, Eli Lilly Japan, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., MSD, Bristol-Myers Squibb KK, Teijin Pharma, Taiho Pharma, Medtronic Japan and ONO Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, outside the submitted work. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

The data underlying this study are available in this article and in the online supplementary material.

Author contributions

Atsushi Kamigaichi: Conceptualization; Data curation; Investigation; Writing—original draft. Keiju Aokage: Conceptualization; Data curation; Supervision; Writing—review & editing. Takashi Ikeno: Formal analysis; Supervision; Writing—review & editing. Masashi Wakabayashi: Formal analysis; Supervision; Writing—review & editing. Tomohiro Miyoshi: Data curation; Supervision. Kenta Tane: Data curation; Supervision. Joji Samejima: Data curation; Supervision. Masahiro Tsuboi: Data curation; Supervision.

Reviewer information

European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery thanks Paola Ciriaco, Milton Saute, Francesco Zaraca and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review process of this article.

REFERENCES

ABBREVIATIONS

- CI

Confidence interval

- CID

Cumulative incidence of death

- CT

Computed tomography

- GGO

Ground-glass opacity

- HR

Hazard ratio

- LN

Lymph node

- LSD

Lobe-specific nodal dissection

- NSCLC

Non-small-cell lung cancer

- OS

Overall survival

- RCT

Randomized clinical trial

- RFS

Recurrence-free survival

- SND

Systematic nodal dissection

- SS

Systematic nodal sampling