-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kazuhito Imanaka, Shunei Kyo, Shin-ichi Ban, Possible close relationship between non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia and cholesterol crystal embolism after cardiovascular surgery, European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Volume 22, Issue 6, December 2002, Pages 1032–1034, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1010-7940(02)00590-0

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A senile patient developed fatal intestinal necrosis right after uneventful cardiovascular operation using usual cardiopulmonary bypass. Cholesterol crystal embolism (CCE) was demonstrated histologically, but angiograms were typical of non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI). Very severe vasoconstriction occurred not only in the superior mesenteric artery but also in other splanchnic arteries. The clinical course strongly suggested that NOMI resulted from CCE and that some humoral factors were released and played very important roles in this case.

1 Introduction

In a 67-year-old male with severe aortic regurgitation and bilateral common iliac artery aneurysms, fatal intestinal necrosis occurred following aortic valve replacement (AVR) and implantation of a bifurcated vascular prosthesis, performed concurrently and both uneventfully. Angiograms were typical of non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI). Histologically, cholesterol crystal embolism (CCE) was demonstrated. Both NOMI and CCE can cause intestinal necrosis, but they are not believed to have a close relationship.

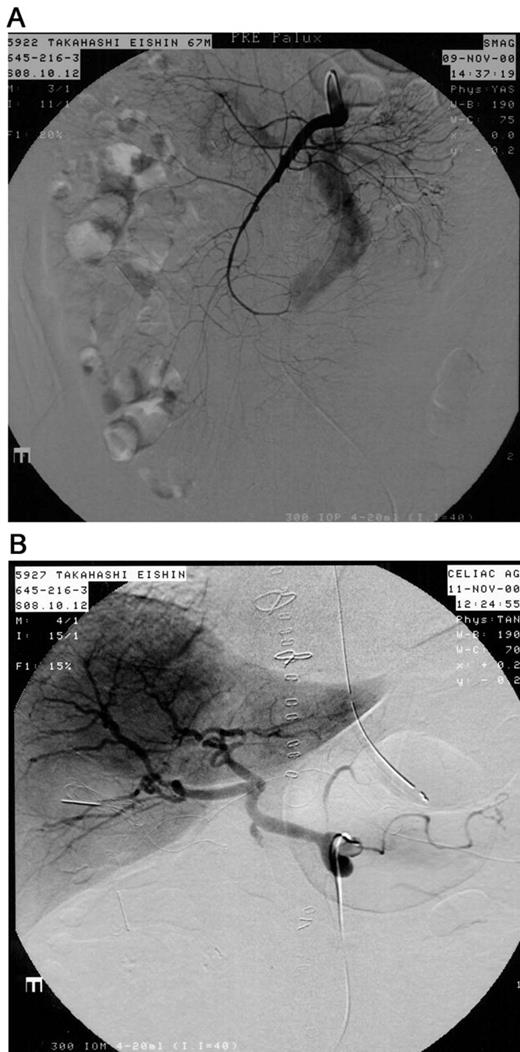

The surgical procedure on this senile patient was unremarkable. AVR was performed with the usual cardiopulmonary bypass and cardioplegic arrest at moderate hypothermia. The arterial cannula was placed onto the ascending aorta which was mildly thickened but was free from severe atherosclerotic changes. Abdominal aorta below inferior mesenteric artery and bilateral common iliac arteries was replaced with a bifurcated vascular prosthesis. There was no visceral or renal ischemic time. Only one lumbar artery originating near the bifurcation of the aorta was ligated during the abdominal aortic surgery. The postoperative hemodynamic condition, including urine output, was very good without inotropes, and calcium-channel blockers (nicardipine hydrochloride 3–6 mg/h) and nitroglycerin (4 mg/h) were administered continuously. Despite normal peripheral pulses and body temperature, many purpuras and livedo reticularis, often observed in patients with CCE, were present in the skin. The patient regained consciousness normally several hours later, and was noted to have paraplegia. Emergency examinations revealed a heavily atherosclerotic descending thoracic aorta, but neither aortic dissection nor spinal lesion was present. During several hours of evaluations of the paraplegia, anuria, abdominal pain and a steep elevation of serum creatinine phosphokinase (CPK) (387→33591 IU/l) acutely developed. Acidosis was absent. Angiography revealed severe widespread narrowing of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) with very slow flow and absence of ileal and jejunal images, all of which are representative of NOMI. Infusion of papaverine hydrochloride and prostaglandin (PG) E1 into the SMA was started, and the patient subsequently underwent emergency abdominal re-exploration. The whole gastrointestinal tract was pale, and two severely ischemic segments in the ileum were resected. After this operation, papaverine (60 mg/day) and PGE1 (20 μg/day) were continuously infused into the SMA, but the serum CPK level did not decrease. Two days later, repeat angiography disclosed unchanged extensive spasm of the SMA, and very severe narrowing of the splenic artery, the left gastric artery, and the gastroduodenal artery. Both renal artery stems looked almost normal, but the kidneys were not visualized. The hepatic circulation appeared to be normal (Fig. 1) . Doses of papaverine and PGE1 were doubled, but no improvement resulted. Cutaneous findings deteriorated, and nose, ears, scrotum, and some fingers and toes became gangrenous. The patient died of septic shock on the 5th postoperative day.

(A) The origin of the superior mesenteric artery appeared to be normal, but its branches were diffusely and severely narrowed. The blood flow was very slow, and the ileum and jejunum were not visualized. (B) The splenic artery, the left gastric artery, and the gastroduodenal artery were also extremely narrowed. Strikingly, the hepatic circulation appeared to be normal.

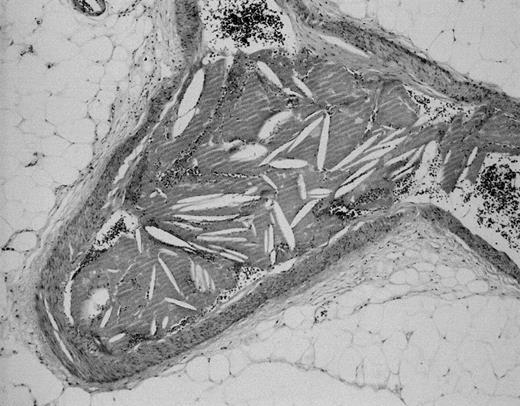

Histological examination of the resected ileum revealed hemorrhagic necrosis of the mucosal layer and CCE in the arterioles and the small arteries (Fig. 2) . Atherosclerotic changes and fresh thrombi were not observed. Histopathologically, therefore, CCE was judged responsible for the fatal intestinal necrosis.

Cholesterol crystal embolism was detected in the arterioles and the small arteries of the resected ileum.

2 Discussion

In this case, the presence of both NOMI and CCE were confirmed. Both entities are highly lethal, but they have not been believed to be closely related with each other.

NOMI is a well-known disorder, but little is yet known about the precise etiology of the vasoconstriction of the SMA. A strong correlation between systemic hypoperfusion and NOMI has been pointed out, and, especially in post-cardiotomy NOMI, low output syndrome is usually a predisposing factor [1,2]. However, this case was completely free of hemodynamic instability or other risk factors such as diabetes or oral digoxin intake. In addition, vasodilators had been administered before diagnosis. These facts strongly suggested an uncommon etiology of NOMI in the present case.

CCE results from atheromatous plaque rupture and microemboli. Diagnosis is made by histologic confirmation of intravascular birefringent cholesterol crystal. As in the present case, CCE is often associated with cutaneous manifestations and causes life threatening multiple organ damage. Pannecrosis of the intestine in CCE has been reported repeatedly [3–6]. However, ischemia during embolism is an essentially local event. Moreover, there is abundant collateral circulation especially in the small intestine, and the extensive vascular plexus there makes it highly resistant to microemboli [7]. In patients with CCE and pannecrosis of the intestine, therefore, some additional phenomenon must be present. Generalized vasoconstriction of the SMA, which took place in this case, is one possible mechanism, although the precise relationship between CCE and NOMI is difficult to demonstrate clinically. CCE is based on findings of histology, NOMI is based on findings of angiography, and these two entities are closely related in cases like the present one. We believe that selective angiography of the SMA and other susceptible vessels is mandatory in every case in which CCE is a real possibility.

Paraplegia after routine cardiac surgery or after surgery on the abdominal aorta far distal to the visceral arteries is a rare occurrence. Its etiology in this case remains unclear, although it also might have been a result of CCE [8].

Another striking aspect of this case was that very severe vasoconstriction was demonstrated not only in the SMA but also in other arteries. Most previous papers regarding NOMI have focused on vasoconstriction in the SMA alone. Some authors have reported successful resolution of NOMI by selective infusion of vasodilators into the SMA [1,2,9,10], but unsuccessful cases are also rather common. The angiograms in this case strongly suggested that some humoral substances had played an essential role in the extensive severe vasoconstriction, and that such substances may selectively affect the arteries that supply the alimentary tract and the kidneys. This hypothesis needs to be clarified by laboratory studies. In any event, in cases like the present one, various therapeutic strategies should be considered in order to save the patients’ life.