-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mikael Elinder, Oscar Erixson, An inquiry into the relationship between intelligence and prosocial behavior: Evidence from Swedish population registers, The Economic Journal, Volume 135, Issue 668, May 2025, Pages 1141–1166, https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueae105

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We investigate the relationship between intelligence and prosocial behaviour, using administrative data on cognitive ability, charitable giving, voting and possession of eco-friendly cars for 1.2 million individuals. We find strong positive associations for all three behaviours, which remain when using twin-pair fixed effects to account for confounders. We also find that general (fluid) intelligence is a stronger predictor than other dimensions of cognitive ability, and that most of the relationship remains after controlling for a set of mediators, suggesting a direct impact on prosocial behaviour. Finally, we show that cognitive ability is also positively related to a survey measure of altruism.

A unique feature of us humans is our inclination to cooperate with non-kins to produce public goods and redistribute resources (Fehr and Fischbacher, 2003; Silk and House, 2011). This type of prosocial behaviour has important implications for nearly all aspects of economic decision-making and the functioning of our societies (Ostrom et al., 2002; Gintis et al., 2005; Henrich, 2018). However, finding a rational explanation for why humans have evolved into a prosocial animal has for a long time constituted a key challenge for evolutionary biologists (Hamilton, 1964; Alexander, 1987; Batson, 1987; Bowles and Gintis, 2011; Henrich, 2018).

In this paper, we investigate whether prosocial behaviours, such as donating money to charities, voting in democratic elections or voluntarily reducing one's carbon footprint, may be explained by another unique human feature—our highly developed intelligence. For this purpose, we analyse high-quality Swedish administrative data containing information on cognitive ability, charitable giving, voting and possession of environmentally friendly cars for 1.2 million individuals.

Scholars in many disciplines have shown an interest in the potential link between cognitive ability and prosocial behaviour. However, no coherent or generally accepted theory has been formulated, and empirical evidence for a causal link is still lacking.

Benjamin et al. (2013) hypothesised that prosocial behaviour (e.g., cooperating in a prisoners’ dilemma) stems from optimisation errors, which should be more common among individuals with a lower cognitive ability. In a series of lab experiments, however, they found little evidence for this hypothesis. Proto et al. (2019), on the other hand, showed that highly intelligent individuals are more likely to cooperate and reach mutually beneficial equilibria with higher payoffs for all players, including themselves. This result may be explained by individuals with a higher cognitive ability being better at understanding the perspectives of others (Herrnstein and Murray, 1994) and that prosocial acts may induce reciprocity among the beneficiaries (Grueneisen and Warneken, 2022) or rewards from outside observers (Millet and Dewitte, 2007).

Another line of reasoning is based on the notion that cognitive ability comes with the ability for logical reasoning and perspective taking, both of which naturally lead to ethical reasoning and altruism (Singer, 1981).1 Individuals with a higher capacity for ethical reasoning would more often conclude that prosocial acts are rational as consciously acting in conflict with one's own ethical principles may result in cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957).2 A related aspect is that cognitive ability improves learning (Cunha and Heckman, 2007), and to the extent that schools teach prosocial values (Helliwell and Putnam, 2007; Willeck and Mendelberg, 2022), individuals with a higher cognitive ability may adopt such values to a higher degree than others.

Individuals with a higher cognitive ability typically also earn more (Lindqvist and Vestman, 2011) and may thus more easily regain resources spent on prosocial behaviours (Bryant et al., 2003; Wiepking and Maas, 2009). A higher cognitive ability would thus be associated with a lower cost for prosocial acts and we would observe more prosocial behaviour among individuals with a higher cognitive ability.3

All these theoretical arguments, except for the argument based on optimisation errors (Benjamin et al., 2013), suggest that intelligence is positively and causally linked to prosocial behaviour.4 Nevertheless, some nuances in the different theoretical arguments allow for empirical analyses to assess their relevance. For instance, if the altruism channel is valid, individuals with a higher cognitive ability would then express more altruistic values, whereas if the cost-of-giving argument is important, one would expect that the relationship between cognitive ability and prosocial behaviour is substantially mediated by income.

Our primary goal in this paper is to evaluate whether there is a positive relationship between cognitive ability and prosocial behaviour and whether such a relationship is likely to reflect a causal link. However, we also try to shed some light on the importance of the different theoretical arguments and the mechanisms through which this relationship may emerge.

Several previous attempts have been made to empirically characterise the relationship between intelligence and prosocial behaviour. One strand of literature has used lab experiments, such as the dictator game and public goods game, to investigate whether intelligence predicts giving. Some of these studies have documented a negative association (Ben-Ner et al., 2004; Kanazawa and Fontaine, 2013; Ponti and Rodriguez-Lara, 2015; Cueva et al., 2016), a few find no association (Brandsäter and Güth, 2002; Benjamin et al., 2013), while others document a positive association between intelligence and generosity toward others in these types of games (Millet and Dewitte, 2007; Chen et al., 2013; Guo et al., 2019; Proto et al., 2019).

Another strand of the literature has relied on surveys containing self-reported measures of prosocial behaviours, such as charitable giving (Bekkers, 2006; Wiepking and Maas, 2009; James, 2011), voting (Deary et al., 2008; Denny and Doyle, 2008), environmentally friendly behaviours (Schneider and Sutter, 2020; Eshchanov et al., 2021), altruism (Falk et al., 2018) and various proxies for intelligence, such as cognitive reflection tests, memory tests, verbal proficiency or self-reported math skills (Bekkers, 2006; Wiepking and Maas, 2009; James, 2011; Falk et al., 2018). Most of these studies document a positive relationship, while Falk et al. (2018) found that it is present in a large number of countries.

We add to this literature by conducting the first large-scale study on the relationship between reliable and objectively reported measures of both intelligence and prosocial behaviour.5 Moreover, while the literature has hitherto focused on whether or not there is an association between intelligence and prosocial behaviour, surprisingly few attempts have been made to assess whether such an association is a consequence of confounding factors correlated with both intelligence and the behaviour in question.6 A positive association could arise without any of the theoretical arguments mentioned above being valid. For instance, more intelligent individuals may be more likely to grow up with parents and peers who promote prosocial values, which, in turn, results in prosocial behaviour. We take this issue seriously and use within-twin-pair variation in cognitive ability to estimate the relationship. By doing so, we effectively account for many potentially confounding environmental and genetic factors. We also control for a well-established measure of personality (sometimes referred to as non-cognitive ability in the economics literature) to account for intelligence being positively correlated with closely related cognitive functions that may influence prosocial behaviour, such as empathy. Moreover, we investigate how the relationship is mediated by education, income, family situation and place of residence. Finally, using survey data from a smaller sample, we investigate whether the relationship between cognitive ability and prosocial behaviour is mirrored in stated altruism.

We measure intelligence using cognitive ability test scores from the Swedish military enlistment process, which was mandatory for men and voluntary for women, and we study three different third-party-reported prosocial behaviours, all observed at the individual level in the administrative registers: charitable giving, voting and possession of eco-friendly cars.

These behaviours are prosocial in the sense that they are generally encouraged, often thought of as benefiting others (typically strangers), and are thus akin to behaviours observed in classical applications of, for example, the dictator game or the public goods game. We do not claim that charitable giving, voting or buying an eco-friendly car are solely, or even mainly, prosocial behaviours, only that these behaviours contain generally accepted prosocial elements. As discussed by, for instance, Schroeder and Graziano (2015), intended helpful behaviours may not always benefit the recipient, which means that no specific behaviour may be considered universally or inherently prosocial, but must always be defined in a social context.7

The perhaps most prominent example of real-life prosocial behaviour is charitable giving. Individuals with more human capital are generally more generous toward charities (e.g., Bryant et al., 2003; Wiepking and Maas, 2009; Bekkers and Wiepking, 2011). However, less is known as to why human capital constitutes such a strong predictor of charitable giving (Bekkers and Wiepking, 2011). Some argue that education fosters an attitude of giving to charity (Wiepking and Maas, 2009), while others have noted that specific abilities, such as verbal proficiency (Bekkers, 2006; Wiepking and Maas, 2009), represent important predictors of charitable giving over and beyond education. These findings point to the potential role of cognitive ability as an independent determinant of charitable giving. In line with this conjecture, James (2011) analysed survey data from the Health and Retirement Study and found that cognitive decline is associated with a lower rate of charitable giving among elderly Americans.

Voting complements charitable giving as a prosocial behaviour in that it incurs a time cost rather than a monetary cost for the donor. In this respect, voting is similar to volunteering.8 Voting in elections is also often modelled and viewed as a prosocial act, or, more precisely, as a civic duty (e.g., Jankowski, 2002; Campbell, 2006; Edlin et al., 2007; Willeck and Mendelberg, 2022). Voting contains various prosocial elements as voting benefits others with similar interests, may contribute to better quality in political outcomes through ‘the miracle of aggregation’ (Converse, 1990) and provides support for democracy and resistance against anti-democratic movements (e.g., Glaeser et al., 2007; Helliwell and Putnam, 2007). A number of studies have been conducted on the link between cognitive ability and political participation (e.g., Dal Bó et al., 2017). This literature has been motivated by the conjecture that the strong positive association between education and voting could be explained by intelligence predicting both educational attainment and political participation (Herrnstein and Murray, 1994).9 In line with this argument, a few studies have also found a positive link between proxies for intelligence and survey data on voting (e.g., Deary et al., 2008; Denny and Doyle, 2008)10 and genetic predispositions for cognitive ability and validated voting data (Aarøe et al., 2021). Similar to Aarøe et al. (2021), we rely on validated voting data. An advantage of using validated turnout data is that this approach avoids the common problem of over-reporting political participation in surveys (for a recent discussion on this issue, see DeBell et al., 2018).

The choice to analyse the possession of an environmentally friendly car (hereafter referred to as an eco-friendly car) as a prosocial behaviour is motivated by the general observation that many behaviours cause negative environmental externalities. Minimising these negative externalities contributes to preserving and managing our common environment (Hardin, 1968; Ostrom, 1990). Since an eco-friendly car typically costs more than a similar conventional car, but emits less pollutants, buying an eco-friendly car is similar in kind to making a contribution in a public goods game. Studies using variation in the average intelligence quotient (IQ) between countries have found that a higher national IQ is associated with higher environmental awareness (Salahodjaev, 2018), less deforestation (Obydenkova et al., 2016) and that it exhibits an inverted U-shaped relation with CO2 emissions (Salahodjaev et al., 2016).11 Moreover, Schneider and Sutter (2020) and Eshchanov et al. (2021) reported results regarding the relationship between cognitive ability and environmentally friendly behaviours (e.g., adopting renewable energy sources, second-hand shopping, energy conservation behaviours) using individual-level survey data. While Eshchanov et al. (2021) found indications of a positive relationship, the estimate regarding cognitive ability in Schneider and Sutter (2020) is statistically insignificant. As far as we know, we are the first to report results regarding the link between intelligence and third-party-reported pro-environmental behaviour at the individual level.

We find a strong positive relationship between cognitive ability and all three prosocial behaviours among men. A one-SD increase in cognitive ability is associated with a 40% increase in the probability of giving to charity, a 31% increase in the probability of voting and a 14% increase in the probability of having an eco-friendly car.

We find similar positive associations between cognitive ability test scores and all three prosocial behaviours in a sample of women having enlisted (∼3,000), thereby suggesting that our findings are not specific to men.

Cognitive ability of the enlistees is assessed through four subtests concerning logical ability, verbal ability, spatial ability and technical comprehension. We find strong positive associations between test scores on all four subtests and all three prosocial behaviours. Interestingly, the strongest associations are found in relation to the subtests measuring logical ability and verbal ability. These subtests are also considered the best measures of general intelligence (or fluid intelligence).

Using within-twin-pair variation in cognitive ability to account for confounders, we find that the estimates are generally lower than the unconditional correlations. However, the estimates still reveal strong associations with all three behaviours. A one-SD increase in cognitive ability is associated with a 26% increase in the probability of giving to charity, a 13% increase in the probability of voting and a 13% increase in the probability of having an eco-friendly car. We interpret these estimates as evidence that the unconditional correlations are substantially biased; however, they also strengthen the case for a real and profound relationship between intelligence and prosocial behaviours.

The twin estimates are slightly reduced when we control for potentially mediating variables (income, education, family situation, municipality of residence). However, with regard to both charitable giving and voting, the relationship remains positive and statistically significant, thus suggesting that there is a direct link between intelligence and prosocial behaviour. The point estimate for an eco-friendly car is still positive, but not statistically significant. Among the mediators, it appears as if years of education is the primary mediator. Somewhat surprisingly, however, income does not appear to be an important mediator.

Finally, we have matched survey responses on self-reported altruism to the cognitive ability test scores for a subsample of individuals (∼600). We find that more intelligent individuals express a higher degree of altruism compared to less intelligent individuals, consistent with Falk et al. (2018).

1. Data

We use administrative data from the Swedish Military Archive covering all men and women alive on 1 January 2016, who enlisted for military service in Sweden between 1969 and 1997.12 Enlistment was at the time mandatory for men and voluntary for women. More than 90% of all men in each birth cohort participated in the enlistment procedure the year they turned eighteen or nineteen. Exemption was granted only to individuals with severe disabilities. More than 1.2 million men and 3,000 women enlisted during this period. The data thus cover almost the entire population of Swedish men born between 1951 and 1979, who on average are in their late forties or early fifties when we measure the outcomes. See Online Appendix Table D1 for additional descriptive statistics regarding the analysis samples. In addressing the role of confounders, we exploit variation within twin pairs, in total 5,786 pairs.13 In Sweden, all individuals have a personal identity number (PIN). We use this PIN to link information from the enlistment records with data from other registers containing data on prosocial behaviours and mediators, which we describe below.

Data on intelligence are obtained from the Swedish Armed Forces’ enlistment procedure, available through the Swedish Military Archives. We measure intelligence using scores from a cognitive ability test taken during the military enlistment. This test has been evaluated by psychologists and is considered good at capturing intelligence (Mårdberg and Carlstedt, 1998; Carlstedt, 2000), as defined by a hierarchical g-factor model (Carroll, 1993). The test consists of four subtests that measure general intelligence (sometimes also referred to as fluid intelligence), but also to some extent crystallised, verbal and spatial intelligence (Carlstedt and Mårdberg, 1993). The test was incentivised, as higher scores led to more attractive positions during the military service, but did not affect the likelihood of being selected for military service (which was mandatory). This is important since, as shown by Duckworth et al. (2011), when intelligence tests are not incentivised, less motivated individuals tend to score lower on the test. If less motivated individuals are also, on average, less prosocial, this could potentially cause a positive bias in our setting. As our measure of cognitive ability is incentivised, it is not likely to be severely affected by this type of bias. We also empirically investigate the importance of this concern in our setting (in Section 3.3 below) and find no indication of such a bias. Moreover, the test score is highly correlated with a test score on a similar cognitive ability test taken at the age of 50–65 (Rönnlund et al., 2015), suggesting that it represents a good predictor of intelligence during the entire adulthood. The enlistment test scores were summarised into a so-called stanine (1–9) scale, which approximates a normal distribution with a mean of 5 and an SD of 2, in which 1 corresponds to IQ < 76, 5 to 96 < IQ < 104 and 9 to IQ > 126 (Öhman, 2015). These test scores have been used and discussed extensively in the literature concerning how intelligence is related to labour market and educational outcomes (Lindqvist and Vestman, 2011; Lundborg et al., 2014; Carlsson et al., 2015; Grönqvist et al., 2017; 2020; Edin et al., 2022; Hermo et al., 2022), health (Hemmingsson et al., 2007; Öhman, 2015; Elinder et al., 2023) and crime (Frisell et al., 2012). With regard to the regression analyses, we follow the previous literature (e.g., Edin et al., 2022) and standardise the cognitive scores to have a mean of zero and unit variance in order to account for the slight drift in scores over cohorts.

Data on charitable giving are retrieved from the Swedish Tax Agency's Income and Tax Register. We use information on individual-level donations to major charities in Sweden during the period 2012–15. These data exist, since donations to charities allowed for tax reductions during this period.14 To get the tax reduction, the donor had to make one or more gifts, each one of at least SEK 200 (≈ USD 20) to a given organisation per year and make a total annual gift amounting to at least SEK 2,000.15 The tax register covers information on all gifts amounting to at least SEK 200, which means that it also covers gifts that did not lead to a tax reduction and gifts that exceeded the maximum amount resulting in a tax reduction (which was SEK 6,000). Importantly, the charity asks the donors for their personal identity numbers (cf. social security number in the United States) and then reports the gift to the tax agency. If eligible, the tax reduction is then automatically calculated, which means that the donor does not need to take any active action to get the tax reduction. This procedure involves important advantages compared to the system of tax deductions for charitable donations used in, for instance, the United States (Clotfelter, 1997), which requires the donor to understand the tax law and actively file forms to receive the tax return. In contrast, the Swedish system minimises the risk of a relationship arising between cognitive ability and charitable giving due to more intelligent individuals being more financially literate (Lussardi and Mitchell, 2014), more familiar with the tax code and potential deductions (Chetty and Saez, 2013) or less willing to try to get a tax reduction.16 Charitable giving is defined as a binary variable taking the value one if the individual has made at least one gift amounting to SEK 200 or more during the period 2012–15 and zero otherwise. In Online Appendices C and D, we provide results for several alternative definitions of charitable giving, such as the donated amount and giving to specific organisations.

Data on voting are obtained from electoral rolls for the Swedish election to the European Parliament on 7 June 2009. Some 7 million Swedes were eligible to vote and the overall turnout was 45.5%.17 The election rolls have been digitised and made available to us by political scientists at Uppsala University via Statistics Sweden. Extensive quality checks show that the resulting data on voter turnout are of very high quality, and they have been used by, for example, Lindgren et al. (2018), who studied the impact of education on voter turnout. We define voting as a binary variable taking the value one if the individual voted in the election and zero otherwise. Voting data are available for a sample of about two-thirds of the population of enlisted men and women.18 In Online Appendices C and D, we also provide results for voting in several other elections.

Data on eco-friendly cars are retrieved from the Swedish Vehicle Register, a population-wide register containing detailed information on all cars registered in Sweden, which enables us to link cars to their owners. A car is considered eco-friendly if its primary or secondary fuel source is ethanol, natural gas, biodiesel or electricity. We define possession of an eco-friendly car as a binary variable taking the value one if anyone in the individual's household owned an eco-friendly car in any year during the period 2007–15 and zero otherwise.19, 20 In Online Appendices C and D, we provide results for several alternative definitions of possession and ownership of eco-friendly cars.

From the Military Archive, we also collect a measure for personal aptitude for military service, henceforth denoted personality, measured at enlistment through a psychological assessment of the enlistee's emotional stability, sociality, persistence and willingness to assume responsibility and take initiative.21 The measure is used as a control variable in the econometric analysis, and we standardise it to have a mean of zero and unit variance.22

Data on mediators (education, income, marriage, presence of children in household, municipality of residence) are collected from the Income and Tax Register, the Education Register and the Multi-Generation Register, described in more detail in Section 3.2 below.

Finally, we complement the analyses with survey data on altruism preferences, described in more detail in Section 4 below.

Further details on the data and how to access them are provided in Online Appendices A and B.

2. The Gradient: Cognitive Ability and Prosocial Behaviour

2.1. Evidence from Men

In Figure 1, we characterise the relationship between cognitive ability and the three prosocial behaviours by displaying the categorical averages of the outcomes per stanine score. We also report estimates of the gradients obtained from the bivariate regression model

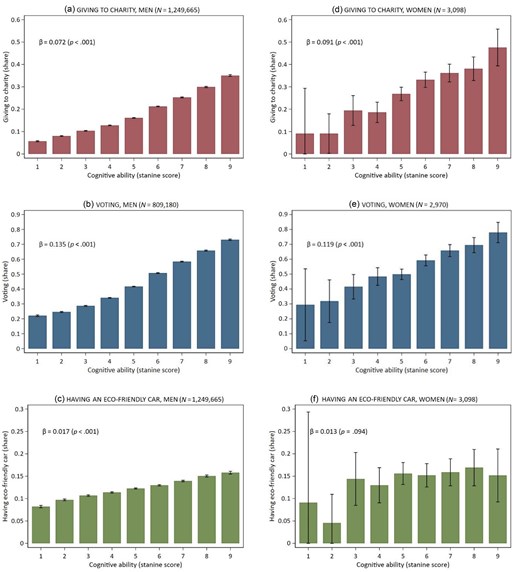

The Relationship between Cognitive Ability and Prosocial Behaviours. Panels (a)–(c) show the relationship between cognitive ability and charitable giving (a), voting (b), and having an eco-friendly car (c), for men. Panels (d)–(f) show the corresponding relationships for women.

Notes: The bars display the categorical averages of the outcome per cognitive ability score together with 95% confidence intervals. The lower end of the confidence intervals for cognitive ability 1 in panel (b) and for cognitive abilities 1 and 2 in panel (f) have been capped at 0. The β coefficients, displayed in the top-left corners, are estimates from the linear bivariate regression model

Panel (a) shows that the incidence of giving increases monotonically over the full range of cognitive ability scores. Men with a top score of 9 are more than five times as likely to make a charitable donation than men with the lowest score of 1 and more than twice as likely than men with the average score of 5. An estimate of the gradient (β) implies that a one-SD increase in cognitive ability is associated with a 7.2-percentage-point or a 40% relative increase in the probability of giving to charity (p < .001).

Panel (b) shows that men with higher cognitive ability scores are on average more likely to have voted and that the share of men who voted increases monotonically over the full range of cognitive ability scores. Men with a top score were more than three times as likely to vote than men with the lowest scores and 70% more likely to vote than men with an average score. The gradient estimate (β) implies that a one-SD increase in cognitive ability is associated with a 13.5-percentage-point or a 31% relative increase in the probability of voting (p < .001).

Panel (c) shows that the share having an eco-friendly car increases monotonically over the full range of cognitive ability scores. The share with an eco-friendly car among men with the lowest cognitive ability score is 8%. Men with a top score were almost twice as likely to have an eco-friendly car than men with the lowest scores and 30% more likely than men with an average score. The gradient estimate (β) implies that a one-SD increase in cognitive ability is associated with a 1.7-percentage-point or a 14% relative increase in the probability of having an eco-friendly car (p < .001).

We also find similar positive associations with regard to several alternative ways of defining charitable giving, voting and having an eco-friendly car (see Online Appendix Figures C2–C16 and Online Appendix Tables D5–D7), and when adding birth-year fixed effects and the personality measure to the regressions (see Online Appendix Tables D2–D4).

2.2. Evidence from Enlisted Women

We also analyse the relationship between cognitive ability and prosocial behaviours among women who enlisted. It should be noted that the sample of women is considerably smaller than that of men, resulting in lower statistical power. It should also be noted that enlistment was voluntary for women, resulting in a selected sample of women. With these caveats in mind, we find positive relationships for women as well; see Figure 1(d)–(f).

The incidence of giving increases over the full range of cognitive ability scores. Women with a top score are five times as likely to make a charitable donation as women with the lowest score and nearly twice as likely as women with the average score. The gradient estimate (β) implies that a one-SD increase in cognitive ability is associated with a 9.1-percentage-point or a 30% relative increase in the probability of donating to charity (p < .001).

Women with higher cognitive ability scores are on average also more likely to have voted, and the share of women who voted increases monotonically over the full range of cognitive ability scores. Women with a top score were more than twice as likely to vote as women with the lowest scores and 50% more likely to vote than women with an average score. The gradient estimate (β) implies that a one-SD increase in cognitive ability is associated with an 11.9-percentage-point or a 21% relative increase in the probability of voting (p < .001).

However, we find no clear indications of a positive relationship between cognitive ability and having an eco-friendly car for women. Taken at face value, the gradient estimate implies that a one-SD increase in cognitive ability is associated with a 1.3-percentage-point or a 9% relative increase in the probability of having an eco-friendly car. However, this estimate is not statistically different from zero (p = .101).

Taken together, the results are largely consistent with the results for men, thus suggesting that the relationship between intelligence and prosocial behaviour is similar for both men and women.

We find similar positive associations when we add birth-year fixed effects and control for personality in the regressions; see column 2 of Online Appendix Tables D2–D4.

2.3. Dimensions of Intelligence

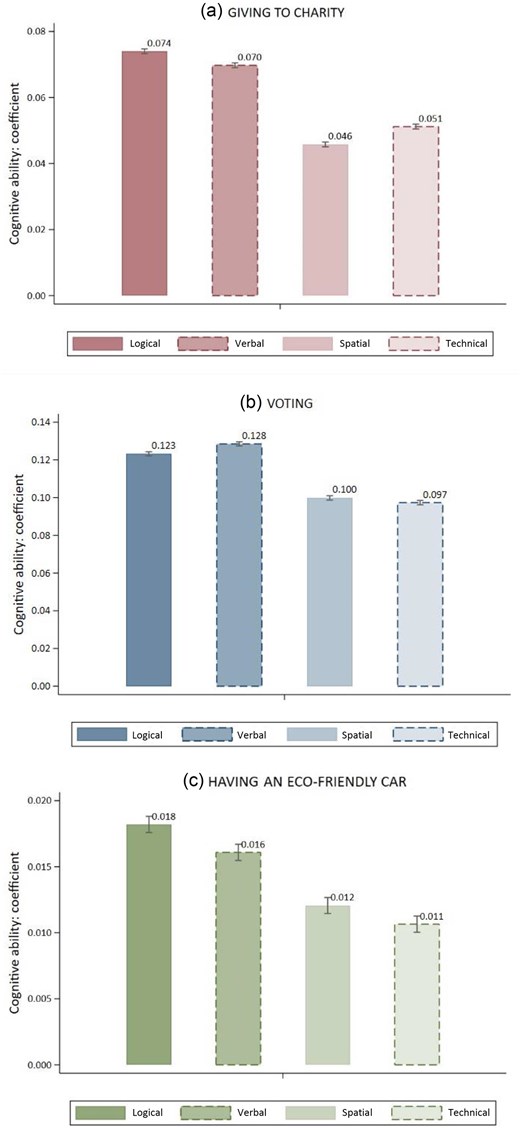

Cognitive ability of the enlistees is assessed through four subtests concerning logical ability, verbal ability, spatial ability and technical comprehension.23 Inspired by a hierarchical g-factor model (Carroll, 1993), each subtest measures a specific dimension of intelligence more reliably than the other subtests (Mårdberg and Carlstedt, 1998). The logical ability test has the highest g-loading and is considered the best measure of general intelligence. The verbal test has a high loading on crystallised intelligence (Gc), the spatial ability test has a high loading on spatial intelligence (Gv) and the technical comprehension test has modest loadings on both crystallised and spatial intelligence. All four tests have significant g-loading, but decrease in the order mentioned (Carlstedt and Mårdberg, 1993). The result of each subtest is summarised on a stanine scale. Panels (a)–(c) of Figure 2 show that test scores on all subtests are positively related to all three prosocial behaviours. They also show that all three prosocial behaviours are more strongly associated with scores on the logical and verbal tests than scores on the other two tests. These results strengthen our belief that general intelligence, and not only some sub-dimension of intelligence, is positively related to prosocial behaviour.

The Relationship between Different Dimensions of Cognitive Ability and Prosocial Behaviours. Panels (a)–(c) show the relationship between dimensions of cognitive ability and charitable giving (a), voting (b), and having an eco-friendly car (c).

Notes: Panels (a) and (c) are based on data on 1,087,113 men and panel (b) on 655,196 men, for whom there are data available on all four separate subtests of cognitive ability. The coefficient estimates and the accompanying 95% confidence intervals are obtained from the linear bivariate regression model

2.4. Conclusion

The above results show that cognitive ability, and especially general intelligence, is positively associated with three prosocial behaviours: charitable giving, voting and possession of an eco-friendly car. This is consistent with the theoretical arguments pointing to a direct link between general intelligence and prosocial behaviour (Singer, 1981; Herrnstein and Murray, 1994; Bryant et al., 2003; Millet and Dewitte, 2007; Proto et al., 2019; Grueneisen and Warneken, 2022). The magnitudes of the associations in our study are also on par with those in many of the previous studies. For example, our finding that a one-SD increase in intelligence is associated with a 31% increase in voting is very similar to the 38% increase found by Deary et al. (2008). Moreover, Wiepking and Maas (2009) found that a one-SD increase in verbal proficiency is associated with an 18% higher donated amount. We find that a one-SD increase is associated with a 40% increased likelihood of giving to charity.

3. The Role of Confounders—Evidence from Twins

The results in the previous section show that there are strong positive associations between cognitive ability and several prosocial behaviours. However, there are many reasons why these relationships may not be causal. A key concern is that intelligence is correlated with other factors, which, in turn, are correlated with prosocial behaviour.

For example, more intelligent individuals are likely to be raised in families with more intelligent parents (Björklund et al., 2010; Grönqvist et al., 2017) who may transmit prosocial values, both genetically (Cesarini et al., 2009) and through their behaviours and expectations (Bekkers, 2006; Wilhelm et al., 2008). This argument holds, not only within the family, but also, to some extent, within peer groups, schools and neighbourhoods.24

Individuals with higher intelligence are also more likely to have been raised in affluent families and well-to-do neighbourhoods (Chetty et al., 2014). Consequently, they may have had limited exposure to environmental hazards (Banzhaf et al., 2019) that can adversely affect cognitive development, including factors like lead (Grönqvist et al., 2020), air pollution (Simeonova et al., 2019) or prenatal alcohol exposure (Nilsson, 2017). If any of these or other environmental factors affect both cognitive development and prosocial behaviour, this could mean that the estimated positive association between cognitive ability and prosocial behaviour may be spurious.

Our approach to mitigate the influence of unobserved genetic, family and environmental factors on our results relies on variation in cognitive ability within twin pairs. Twin-based methods, extensively employed in economics and various other disciplines for similar purposes (e.g., Behrman, 2016), offer a valuable tool in this regard. Given that twins typically share similar prenatal environments, are raised by the same parents, attend the same schools and are influenced by the same peer groups during their upbringing, this methodology effectively controls for common family and environmental confounding factors.25 Moreover, it partly addresses confounding due to genetics. Therefore, any remaining variation is attributed to differences in non-shared environments and non-shared genetics.26

However, it remains possible that the association may be confounded by personality traits other than cognitive ability that are correlated with both cognitive ability and prosocial behaviour. For a long time, the Big Five personality traits, with the exception of openness, have been thought to be uncorrelated, or only exhibit a weak correlation, with intelligence (Matthews et al., 2009). A recent meta study confirms this, but also notes that cognitive ability and some subcomponents of personality are significantly correlated (Stanek and Ones, 2023). For instance, despite a near-zero correlation between general intelligence and agreeableness, the two subcomponents empathy (interpersonal sensitivity) and compassion have been found to be positively correlated with general intelligence (ρ = 0.20 and ρ = 0.26, respectively). Moreover, Guo et al. (2019) showed that empathy is related to both intelligence and prosocial behaviour. Likewise, the cognitive ability measure in our data is positively correlated with the scores on the personality test (described in Section 1),27 which, in turn, is correlated with three prosocial behaviours. Hence, we control for the personality measure in the regression models.

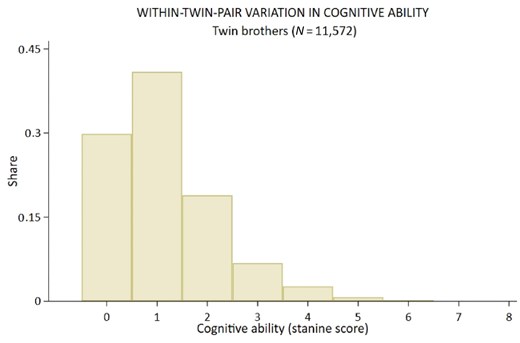

The enlistment data contain a total of 5,786 pairs of male twins and Supplementary Table S1 in Online Appendix D shows that the twins are very similar to the population at large in terms of observable characteristics and, importantly, with regard to cognitive ability and prosocial behaviours. In Figure 3, we display the variation in cognitive ability used in the analysis, calculated as the difference between the maximum and minimum stanine scores in the twin pair. We see that, for 70% of the twin pairs, there is a difference of one or more stanine points, while for 30%, the difference exceeds one SD (two stanine points).

The Distribution of Within-Twin-Pair Differences in Cognitive Ability.

Notes: The figure is based on data on 5,786 twin pairs (11,572 twins). The within-twin-pair difference is calculated as the difference between the maximum and minimum values of cognitive ability in the twin pair. See the main text and Online Appendix A for details about the variables and sample.

The regression model with twin fixed effects takes the form

where

3.1. Twin Fixed-Effect Estimates

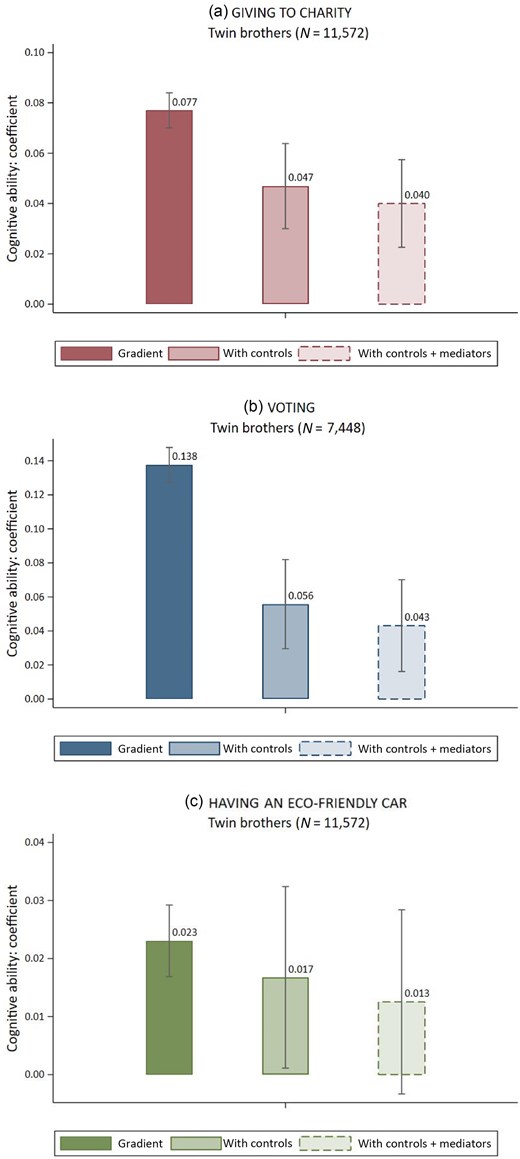

The left-hand bars of panels (a)–(c) in Figure 4 show that the gradients for twins are nearly identical to the gradients in the population (0.077 versus 0.072; 0.138 versus 0.135; 0.023 versus 0.017). The middle bars show the

The Role of Confounders and Mediators for the Relationship between Cognitive Ability and Prosocial Behaviour. Panels (a)–(c) show estimates of the relationship between cognitive ability and charitable giving (a), voting (b), and having an eco-friendly car (c).

Notes: The left-hand bars display regression estimates of cognitive ability and accompanying 95% confidence intervals from the model

In Online Appendix Tables D14–D16, we report results for the different dimensions of intelligence, using models with twin fixed effects. These confirm that the strongest relationships are found with regard to the logical test, followed by the verbal test.

It is worth commenting on the role of personality. Supplementary Tables D11–D13 in Online Appendix D show that the personality measure is uncorrelated with all three prosocial outcomes, conditional on cognitive ability and twin-pair fixed effects. This is noteworthy, given that several studies investigating other types of outcomes such as schooling, earnings and health have found that this personality measure is a stronger predictor than cognitive ability (e.g., Lindqvist and Vestman, 2011; Öhman, 2015; Edin et al., 2022).28

However, it should be noted that our findings do not rule out that other personality traits also serve as important determinants for prosocial behaviour. In particular, it would be interesting to assess to what degree specific personality traits such as emotional intelligence, empathy and theory of mind are linked to prosocial behaviour (Wiepking and Maas, 2009; Klimecki et al., 2016). Unfortunately, such data are not readily available in Swedish registers or surveys.

3.2. Mediators and Mitigators

An effect of higher intelligence on prosocial behaviours may be explained by various mediating or mitigating mechanisms. For instance, more intelligent young individuals are more likely to proceed with (Edin et al., 2022) and gain from education (Cunha and Heckman, 2007), earn more (Lindqvist and Vestman, 2011), find a partner and become a parent (Heckman et al., 2006) and sort into high-status neighbourhoods (Schachner and Sampson, 2020).

Each of these factors may also promote prosocial behaviours (Bekkers and Wiepking, 2012). For instance, education may transmit social norms and foster moral reasoning (Helliwell and Putnam, 2007), as well as increase the level of awareness concerning the needs and well-being of others (Bekkers and Wiepking, 2012). Income, in turn, is positively related to both charitable giving (Meer and Priday, 2021) and voting (Wolfinger and Rosenstone, 1980). Moreover, being a parent may also turn an individual's focus more toward the family rather than toward others, thus mitigating prosocial behaviour (Elinder et al., 2021). Finally, it has been shown that there are peer effects on prosocial behaviours, such as charitable giving (Smith et al., 2013), voting (Barber and Imai, 2013) and having an environmentally friendly car (Tebbe, 2023), in particular at the geographical level (Tebbe, 2023).

The right-hand bars in panels (a)–(c) in Figure 4 show coefficient estimates of the association between cognitive ability and the three prosocial behaviours when controlling for years of education, educational track, log of income (labour and capital), being married, having children and the municipality of residence (as well as twin-pair fixed effects and personality).29 For all three behaviours, the coefficient estimates decrease a bit, and the coefficient estimate with respect to owning an eco-friendly car is now statistically insignificant (p = .109). These results thus indicate that there is an important and strong direct link between intelligence and prosocial behaviours. Among the different mediators, only years of education seems to account for the drop in the coefficient estimate of cognitive ability (see Online Appendix Tables D11–D13). This means that the drop in the coefficient estimate on cognitive ability cannot be explained by individuals with a higher cognitive ability earning more, choosing different educational tracks, having a different family situation or living in different municipalities.30

3.3. Measurement Errors

Although our measure of cognitive ability is generally considered to be of high quality in terms of both reliability and validity, it is nevertheless possible that some errors were introduced in the measuring process. Hence, we address the potential influence of two types of measurement errors. First, we try to evaluate the sensitivity of our results to classical measurement errors. Second, we address the potential that the cognitive ability test scores to some extent also capture individuals’ motivation to do military service. Reassuringly, the results presented above only appear to be marginally affected by these types of measurement errors.

3.3.1. Classical measurement errors

Classical measurement errors in the cognitive ability test may arise for several reasons. The test subject may, for example, have an unusually good or bad day (e.g., due to good or bad sleep) or the particular set of questions selected for the test randomly happened to be unusually easy or hard.31 The test scores may thus be a noisy measure of the individual's ‘true’ cognitive ability. In our setting, this would lead to the estimates of the relationship between cognitive ability and prosocial behaviours being affected by attenuation bias (e.g., Wooldridge, 2006). This problem may be further aggravated in models relying on within-family variation (Griliches, 1979). But it may also be smaller in models relying on within-family variation if the causes of the measurement error are correlated within the family. If so, part of the measurement error is netted out with family fixed effects. For instance, it is easy to imagine that two twin brothers might have had a bad or good night's sleep for the same reason.

Similar concerns apply to the other enlistment tests. The fact that we standardise the variables partly mitigates this issue. If the reliability ratios32 of the variables measured with errors are known, it is possible to obtain consistent coefficient estimates by using the errors-in-variables estimator (Draper and Smith, 1998). Lindqvist and Vestman (2011) calculated and reported reliability ratios for both the cognitive ability and personality measures, using test scores from the Swedish enlistment process for a sample of twins.33 The reliability ratio for cognitive ability is 0.8675, while it is 0.70267 for personality, thus indicating that cognitive ability is measured with less error than personality. In Online Appendix Tables D17–D19, we reproduce the main results using reliability ratios for the cognitive ability and personality measures. The estimates corrected for measurement errors are approximately 10–14% larger than the corresponding non-corrected estimates. Hence, the potential attenuation bias stemming from measurement errors may be relatively small (compared to, e.g., the confidence intervals). Moreover, restricting the sample to twin pairs, in which both twins have enlisted on the same day (about 80% of the sample) and thus exhibit more correlated measurement errors, yields estimates that are akin to the main estimates, supporting the conclusion that measurement errors play a minor role. The approach, using reliability ratios, to correct for measurement errors relies on several restrictive assumptions, such as uncorrelated measurement errors within twin pairs, which are hard to validate and most likely not completely fulfilled. Another common approach to account for measurement error is to instrument cognitive ability with another measure of cognitive ability (Grönqvist et al., 2017). A more efficient extension of this approach, the Obviously Related Instrumental Variables (ORIV) estimator, was developed by Gillen et al. (2019) and applied to a within-family estimator by van Kippersluis et al. (2023). The ORIV estimator uses multiple measures of, in our case, cognitive ability as instruments for each other. A key assumption of this approach is that the measurement errors are uncorrelated between the different measures, which is reasonable if one test happens to consist of unusually easy questions for a particular enlistee. However, if the enlistee has a bad day then measurement errors between the tests are likely to be correlated. We complement the analysis by also applying the ORIV method, using the test scores on the logical and the verbal tests as two measures of cognitive ability. We use the logical and verbal tests as they have been found to have the highest g-loadings, and as they are both similarly correlated with the outcomes (see Figure 2). The ORIV estimates show that twin fixed-effect estimates suffer from attenuation bias (see Supplementary Table S20). In general, the measurement error-corrected coefficients are about twice as large. While this approach relies on different assumptions than the approach using reliability ratios, it is hard to assess which approach is more reliable in our setting. Taken together, measurement errors appear to cause a bias toward zero in our setting.

3.3.2. Does cognitive ability also capture motivation?

Suppose that a person who is highly motivated to do military service exerts more effort in the enlistment tests and thus obtains better test results. If motivation to do military service is correlated with an omitted factor, which is an independent determinant for prosocial behaviour (e.g., willingness to make sacrifices for the good of society), then the coefficient estimates regarding cognitive ability may be upward biased. This is a tricky problem to handle. However, we try to assess the importance of this concern by controlling for another test score, which is likely to be equally affected by motivation-driven effort, but does not plausibly affect prosocial behaviour through any other channel than being a proxy for the omitted variable. For this purpose, we collect the scores from a physical endurance test taken during the enlistment procedure.34 In Online Appendix Tables D17–D19, we first show that physical endurance is indeed unrelated to the three prosocial behaviours and, second, that the relationship between cognitive ability and these behaviours is essentially unaffected when controlling for physical endurance. We also show, in Online Appendix Tables D17–D19, that our main results are robust to the exclusion of twin pairs, in which at least one of them scored very low (1 or 2) on the cognitive ability test. Our concern is that very low test scores could be more prone to motivation-driven measurement errors if they are the result of low effort. These robustness results and the fact that enlisting individuals had incentives to do well on the enlistment tests lead us to conclude that motivation to do military service is unlikely to lead to a substantial bias in the coefficients of interest. After all, scoring low was not a cause for being exempted from military service, but would result in a less attractive position.

3.4. Conclusion

The twin estimates suggest that the positive association between cognitive ability and prosocial behaviour is unlikely to be a direct consequence of only unobserved confounding factors. Yet, such factors appear to explain about half of the cross-sectional relationship. This should be kept in mind when interpreting the results from studies that do not properly account for such confounders. It should, however, be noted that some unobserved factors correlated with both intelligence and prosocial behaviour may remain unaccounted for in our empirical strategy. Moreover, part of the relationship seems to be mediated through education, but not through any of the other mediators, such as income. The fact that education mediates this relationship is consistent with either education fostering prosocial values or furthering the development of abilities related to, for instance, ethical reasoning. Finally, when we use various approaches to account for measurement errors, we find that such errors tend to bias the estimates slightly towards zero, suggesting that the ‘true’ effects might be larger than what our twin fixed-effect estimates suggest.

4. Survey Evidence—Stated Altruism

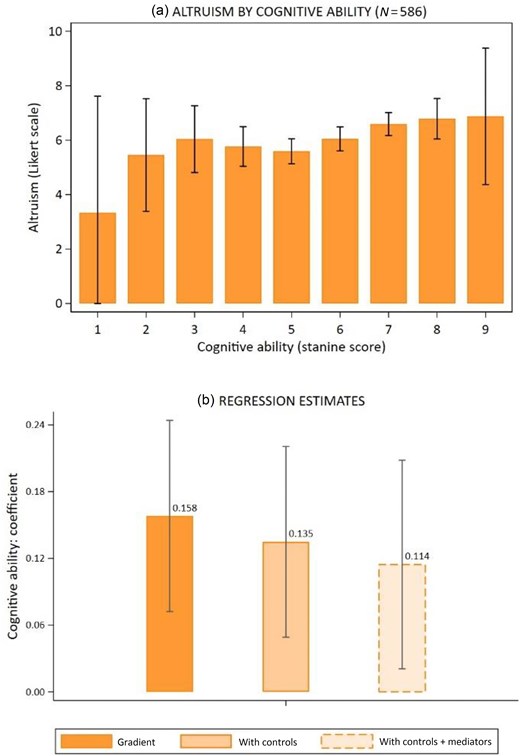

We have shown that cognitive ability is positively associated with three different prosocial behaviours. However, it would be interesting to see how our measure of cognitive ability relates to a commonly used survey measure of altruism, such as that used by Falk et al. (2018). For this purpose, we have matched survey responses on self-reported altruism (scale 0–10), as well as risk preferences and patience,35 for a subsample of men (N = 586) who participated in the military enlistment process. See Elinder et al. (2020) and Online Appendix A for details about the survey.36

Figure 5(a) shows that the degree of altruism increases over the range of cognitive ability scores. The first bar of panel (b) displays the gradient estimate from a bivariate regression, and it implies that a one-SD increase in cognitive ability is associated with a 0.16-SD increase in altruism (p < .001). The second and third bars of panel (b) show the coefficient estimates of cognitive ability when we control for age, age2, risk preferences and patience,37 as well as a set of mediators38 similar to those used in Section 3.2. The relationship weakens somewhat when including controls and mediators, but it remains positive and statistically significant (p < .01 and p = .017).39

The Relationship between Cognitive Ability and Stated Altruism.

Notes: The bars in panel (a) display the categorical averages of the outcome per cognitive ability score. The left-hand bar in panel (b) displays regression estimates of cognitive ability and accompanying 95% confidence intervals from the model

These results suggest that individuals with a higher cognitive ability perceive themselves as more altruistic, which is in line with the findings of Falk et al. (2018).40 While the results do not provide enough information to firmly discriminate between different theoretical mechanisms, it is worth noting that they are clearly consistent with theories suggesting that cognitive ability influences prosocial behaviour through ethical reasoning and altruism (e.g., Singer, 1981).

5. Discussion

Our results offer several new insights on the relationship between intelligence and prosocial behaviour. First, we find strong links between cognitive ability and all three measures of prosocial behaviour in a sample covering essentially the entire population of Swedish men born between 1951 and 1979. Similar links are also found for the smaller sample of women. The three different measures of prosocial behaviour complement each other, such that charitable giving concerns monetary donations and is similar in kind to giving in dictator games, whereas voting and choosing an eco-friendly car are akin to cooperation in social dilemmas such as public goods games. While buying an eco-friendly car requires the sacrifice of monetary resources, voting incurs a time cost. Moreover, we also find that the positive associations between cognitive ability and prosocial behaviours are mirrored in stated altruism. Despite our aim to capture a variety of prosocial behaviours, such behaviours may take many different forms. It is possible that less intelligent individuals may be equally or more prosocial in other ways (e.g., volunteering). However, several studies have found that less intelligent individuals are more likely to engage in antisocial behaviour, such as committing crimes (see, for example, Heckman et al., 2006; Frisell et al., 2012).

The positive relationship between cognitive ability and prosocial behaviour remains even after controlling for common family and environmental background and shared genes, thus suggesting a deeper link between intelligence and prosocial behaviour. While our results indicate that general intelligence is the cognitive function offering the best explanation for prosocial behaviour, a key challenge for future research is to improve our understanding of the relative importance of other closely related cognitive functions, such as empathy and theory of mind, with regard to prosocial behaviour (Singer and Fehr, 2005), as well as their potential interactions with intelligence.

Perhaps surprisingly, we find no evidence of more intelligent individuals being more prosocial just because they earn more, even though we do find support for education serving as an important mediator. However, the mediation analysis also suggests that intelligence has a direct impact on prosocial behaviour.

The results presented here also provide input to theories on the development of human cooperation and the success of our species (Henrich, 2018). The cultural brain hypothesis (CBH) states that human cooperation and cognitive ability are transmitted and selected for, from generation to generation, through cultural selection (Henrich, 2018). The CBH is able to explain the increase in human brain size over time (Muthukrishna and Henrich, 2016) and is also consistent with the increased levels of IQ observed in many countries over the last century (Flynn, 1984; 1987). If intelligent individuals contribute more to solving social dilemmas, as our results suggest, then an important self-reinforcing mechanism should be added to theories on the coevolution of human cooperation and cognitive ability.

If the results presented here generalise to other domains of prosocial behaviour, we will be in a better position to understand several important challenges facing humanity, such as why individuals differ in their attitudes toward taking costly actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Early adopters of such prosocial behaviours would then have better cognitive abilities, which means that extrinsic rewards or nudges may be more effective than moral arguments when it comes to increasing the number of followers.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Online Appendix

Replication Package

Notes

The authors are grateful for helpful comments and suggestions from many scholars, in particular Niklas Bengtsson, David Cesarini, Ian Deary, Siegfried Dewitte, Per-Anders Edin, Per Engström, James Flynn, Ulrich Glogowsky, Joseph Henrich, Stephen Knowles, Aleksey Kolpakov, Matthew Lindquist, Erik Lindqvist, Ben Marx, Mattias Nordin, Paul Nystedt, Eugenio Proto, Jesse Shapiro, Peter Singer, Uwe Sunde, Benno Torgler, Mattias Öhman, as well as seminar participants at Brisbane University of Technology, University of Otago, Uppsala University, LMU Munich, Swedish Institute for Social Research (SOFI), Jönköping University, the Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IFN) and participants at the IIPF conference 2019, the MPSA meeting 2022, the Swedish Conference in Economics 2022 and the EEA-ESEM meeting 2023. We are also grateful to Daniel Waldenström and Sven Oskarsson for generously sharing data. Some of the work was carried out when Mikael Elinder enjoyed the hospitality of the Department of Economics, University of Otago. We would also like to thank Jan Wallanders och Tom Hedelius stiftelse samt Tore Browaldhs stiftelse (P19-0138) and Stiftelsen Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (P19-0448). The Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Etikprövningsmyndigheten) has approved the research conducted in this study (reference numbers 2017/408, 2017/411, 2020–01685).

Footnotes

Intelligence and related cognitive abilities such as empathy and theory of mind may all be the product of a well-developed brain, suggesting that a higher cognitive ability and sensitivity to the well-being of others may result from high functionality in the same brain centres. There is some support for this link in neuroimaging and electroencephalographic studies, which have found that specific centres in the brain are involved in both emotional and cognitive tasks. For instance, the anterior cingulate cortex regulates both cognitive and emotional processing (Bush et al., 2000).

As intelligence arguably offers many important survival advantages, intelligence and prosocial behaviour may coevolve as long as intelligence increases fitness more than prosocial behaviour decreases it.

This argument relies on the assumption that individuals would like to behave prosocially, but that the cost may sometimes prevent them from doing so.

An exception is James (2011), who studied the relationship between cognitive decline and charitable giving in survey data covering elderly Americans using an individual fixed-effect approach.

Also, note that we do not make any assumptions regarding the motives (e.g., self-interest or altruism) for prosocial behaviour.

Using survey data, Denny (2003) found that literacy is positively correlated with volunteering after controlling for education.

See Lindgren et al. (2018) for a recent example of how education affects voting.

Hillygus (2005) found a positive correlation between SAT scores and political engagement in survey data covering American college graduates.

Several studies have studied the link between other individual characteristics and environmental attitudes; see, e.g., Torgler and Garcia-Valiñas (2007).

After 1997, the Swedish Armed Forces had to cut costs and could not afford to let all men go through the enlistment procedure. Hence, men who participated in the enlistment procedure after 1997 are no longer representative of all physically and mentally able men of their birth cohorts.

We identify twin pairs as two individuals who share a biological mother and biological father, according to the Multi-Generation Register, and quarter of birth year from the Income and Tax register.

The recipient organisation had to be a tax-exempted foundation or other non-profit organisation engaged in charity work for the economically needy or in the promotion of scientific research, as well as approved by the Tax Agency. The approved organisations received 80% of all funds collected by all 405 organisations accredited by the Swedish Fundraising Control (a non-profit organisation with the purpose of monitoring and collecting statistics on the fundraising activities of the accredited organisations), and the gifts observed in the tax register account for 47% of all charitable gifts to the organisations approved by the Tax Agency. The remaining 53% come from bequests, donations from organisations, as well as small and anonymous gifts from individuals.

The tax reduction was 25% of the gift amount and could amount to a maximum of SEK 1,500 per year, corresponding to a total annual gift amount of SEK 6,000.

One potential concern with the data on charitable giving is that people's decision to donate could be driven by extrinsic (monetary) incentives associated with the tax reduction rather than by prosocial motives. There are two reasons why this appears to be of limited significance. First, statistics from the umbrella organisation for charities in Sweden reveal no clear surge in donations following the introduction of the tax reduction in 2012 (Swedish Fundraising Association, 2021). Second, if monetary incentives serve as key drivers for charitable gifts, we would expect to see bunching at the threshold for the tax reduction of SEK 2,000. Comfortingly, however, there is no clear excess mass at the threshold value, as seen in Online Appendix Figure C1. The clear spikes are at SEK 200, which indicates one eligible gift, at SEK 1,000, indicating bunching at even amounts, and at SEK 2,400, which is likely to capture repeated monthly donations of SEK 200.

The turnout is low in comparison to the turnout in general Swedish parliamentary elections at around 90%. However, we see the relatively low turnout as an advantage from an analytical perspective, since it offers us more variation to be used in the estimations of the relationship between cognitive ability and voting.

The voting population is restricted to individuals born in 1960 or later, in total 809,180 men and 2,970 women.

The Vehicle Register is available from 1985, even though we only use data for the period 2007–15. The reason for starting in 2007 is that this is when eco-friendly cars became widespread in Sweden. The so-called pump law was enacted in 2006, which forced all gas stations selling more than a certain volume of fuel to also offer renewable fuel. Most gas stations chose to invest in ethanol pumps (those that could not afford this investment had to close down their business), and Sweden saw a sharp increase in the number of ethanol cars in the following years. Electric cars and electric hybrids became widespread a few years later, in the 2010s, and with them the availability of charging stations.

An individual could be the registered owner of several cars. It is also possible that an individual is not a registered owner of a car, but that he or she lives with a partner who owns a car. This is why we define an individual as having an eco-friendly car if there is at least one eco-friendly car registered to someone in the individual's household (including the individual him- or herself).

Personality is assessed through a 20–30-minute interview with a psychologist. In preparation for the interview, the psychologist has information on scores from the cognitive ability test, school grades, as well as the enlistee's answers to eighty questions regarding family conditions, social relationships, etc. The interview as such follows a specific confidential manual on topics to discuss and how to grade the enlistee's answers.

This measure is commonly referred to as non-cognitive ability in the economics literature and has been used previously in research relating it to labour market and educational outcomes; see, e.g., Lindqvist and Vestman (2011), Lundborg et al. (2014), Carlsson et al. (2015), Grönqvist et al. (2017; 2020), Edin et al. (2022) and Hermo et al. (2022). With regard to health, see, e.g., Öhman (2015).

The logical ability test measures how well the individual understands written instructions and applies these in order to solve problems. In the verbal ability test, the individual is supposed to match a word to its synonym out of a set of four potential synonyms. The spatial ability test is aimed at testing the individual's ability to identify the correct two-dimensional plan drawing from a series of drawings of fully assembled three-dimensional objects. The test concerning technical comprehension measures the individual's knowledge regarding physics and chemistry (Öhman, 2015).

Much of the environment is shared during childhood and adolescence, but as the twins age, less of the environment is likely to be shared.

We do not have information on zygosity in these data. In the overall population of twins, the incidence of monozygotic (dizygotic) twins is about 30% (70%). In a population of same-sex twins, the incidence is expected to be 50%. The variation in cognitive ability is likely to be much higher between dizygotic twins than between monozygotic twins (Lindqvist and Vestman, 2011). Thus, most of the variation in cognitive ability used for identification is likely to stem from genetic variation.

The Pearson correlation coefficient between cognitive ability and personality is 0.38 in the full sample of enlisted males and 0.41 for male twins.

Previous studies also indicate that specific personality traits such as agreeableness, emotional stability, self-esteem, etc. play an important role in relation to prosocial acts in general (e.g., Ben-Ner et al., 2004; Klimecki et al., 2016), as well as for deciding whether to donate to charity (e.g., Wiepking and Maas, 2009).

Education is measured as the number of years of completed education in 2015 (or 2009 for voting) as reported in the Education Register. Educational track is collected from the Education Register and provides information on the field of specialisation of the highest obtained degree by means of ten categories (0, general education; 1, education and teacher training; 2, humanities and arts; 3, social sciences, law, commerce and administration; 4, science, mathematics and computing; 5, technology and manufacturing; 6, agriculture, forestry and veterinary medicine; 7, health and social care; 8, services; 9, unknown). These categories are entered as fixed effects in the regressions. Income is measured as the log of the average of the sum (+1) of annual pre-tax labour and capital incomes, reported in the Income and Tax Register, during the same period that the prosocial behaviour is measured. Married is an indicator variable for being married, as reported in the Income and Tax Register, in any of the years for which the prosocial behaviour is measured. Parent is an indicator variable for being a parent to a (living) child, as reported in the Multi-Generation Register, in any of the years for which prosocial behaviour is measured. Municipality of residence is collected from the Income and Tax Register for the first year for which the outcome is measured (i.e., charitable giving in 2012, eco-friendly car in 2007, voting in 2009). Municipality of residence is entered as fixed effects in the regressions.

In Online Appendix Tables D2–D4 we report results from a mediation analysis for the full population. Also, in this analysis, education appears as the most important mediator and the coefficients on cognitive ability remain positive and statistically significant.

Individuals were not allowed to be sick during the enlistment process. If they were sick, they were rescheduled to another day.

The reliability ratio, also referred to as the signal-to-noise ratio, can be defined as

To obtain the reliability ratios, they rely on a comparison between monozygotic and dizygotic twins.

The test is intended to measure the enlistee's fitness level and it is carried out on a stationary bike, which gradually increases the resistance until the enlistee reaches the requirements or when he/she can no longer cope. The test result is reported on a stanine scale. For the econometric analysis, we standardise it to have a mean of zero and unit variance.

As we cannot observe the personality measure from the enlistment in these data, we have instead obtained data on these preferences.

Unfortunately, according to the agreement with the survey respondents, we are not allowed to link the survey data to the administrative data on prosocial behaviours and investigate any possible associations between preferences and behaviours.

Unfortunately, we do not have access to a larger set of relevant predetermined characteristics.

The mediators are collected from the LISA database, which contains data from several administrative registers and includes years of schooling, income (log of disposable income), an indicator for being married and an indicator for being a parent.

Detailed regression results are provided in Online Appendix Table D21.

The discrepancy between our estimate (0.16) and that of Falk et al. (2018) (0.04) may be partially due to the fact that the measure of self-reported math ability used by Falk et al. (2018) is a proxy for intelligence. The survey we use includes the math question in Falk et al. (2018), which asks the respondent to rate his/her math skills on an eleven-point Likert scale. The correlation between cognitive ability and math ability in our data is 0.41.

References

Supplementary data

The data and codes for this paper are available on the Journal repository. They were checked for their ability to reproduce the results presented in the paper. The authors were granted an exemption to publish parts of their data because access to these data is restricted. However, the authors provided the Journal with temporary access to the data, which enabled the Journal to run their codes. The codes for the parts subject to exemption are also available on the Journal repository. The restricted access data and these codes were also checked for their ability to reproduce the results presented in the paper. The replication package for this paper is available at the following address: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14179064.