-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mahmoud Tantawy, Ghada Selim, Marwan Saad, Marwan Tamara, Sameh Mosaad, Outcomes with intracoronary vs. intravenous epinephrine in cardiac arrest, European Heart Journal - Quality of Care and Clinical Outcomes, Volume 10, Issue 1, January 2024, Pages 99–103, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjqcco/qcad013

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS) guidelines recommend intravenous (IV) and intraosseous (IO) epinephrine as a basic cornerstone in the resuscitation process. Data about the efficacy and safety of intracoronary (IC) epinephrine during cardiac arrest in the catheterization laboratory are lacking.

To examine the efficacy and safety of IC vs. IV epinephrine for resuscitation during cardiac arrest in the catheterization laboratory.

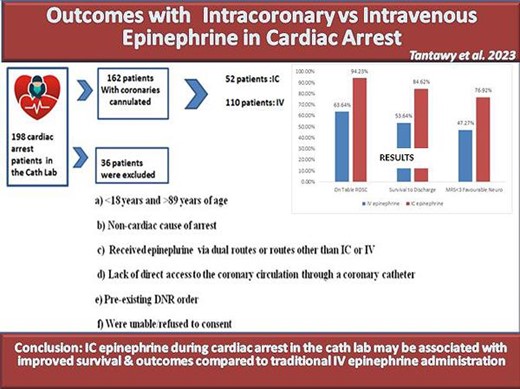

This is a prospective observational study that included all patients who experienced cardiac arrest in the cath lab at two tertiary centres in Egypt from January 2015 to July 2022. Patients were divided into two groups according to the route of epinephrine given; IC vs. IV. The primary outcome was survival to hospital discharge. Secondary outcomes included rate of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), time-to-ROSC, and favourable neurological outcome at discharge defined as modified Rankin Scale (MRS) <3. A total of 162 patients met our inclusion criteria, mean age (60.69 ± 9.61), 34.6% women. Of them, 52 patients received IC epinephrine, and 110 patients received IV epinephrine as part of the resuscitation. Survival to hospital discharge was significantly higher in the IC epinephrine group (84.62% vs. 53.64%, P < 0.001) compared with the IV epinephrine group. The rate of ROSC was higher in the IC epinephrine group (94.23% vs. 70%, P < 0.001) and achieved in a shorter time (2.6 ± 1.97 min vs. 6.8 ± 2.11 min, P < 0.0001) compared with the IV group. Similarly, favourable neurological outcomes were more common in the IC epinephrine group (76.92% vs. 47.27%, P < 0.001) compared with the IV epinephrine group.

In this observational study, IC epinephrine during cardiac arrest in the cath lab appeared to be safe and may be associated with improved outcomes compared with the IV route. Larger randomized studies are encouraged to confirm these results.

Introduction

Cardiac arrest is the most dreaded complication of patients with heart disease. Healthcare professionals and medical teams across the world strive to put in place strategies aimed at improving the clinical outcome for all in-hospital arrest patients, including timely intervention and post-arrest care with the primary goal of improving survival and discharge from hospital rates as well as minimizing the probability of neurological insults. It is, therefore, not surprising that the response time to in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) is generally shorter than out-of-hospital arrest, as the arrests are frequently witnessed, leading to a reduced ischaemic burden time [i.e. the time between the onset of the arrest and return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC)].1 Literature indicates that around 3% of IHCAs occur in the cath lab, and 1.3% of patients who undergo cardiac catheterization experience a cardiac arrest.2

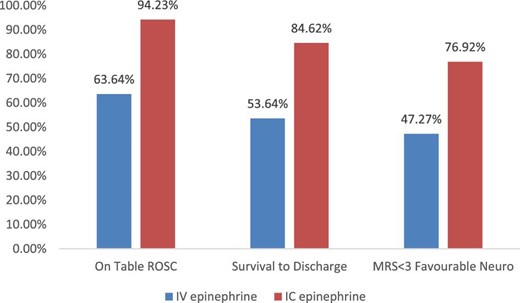

Clinical outcomes between intravenous vs. intracoronary epinephrine.

IC epinephrine has proved its efficacy in the management of no-reflow phenomenon using a dose of 0.1 mg diluted.3–6 Furthermore, a small study from Korea, including 30 patients with severe hypotension during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) showed that IC epinephrine (0.1–0.2 mg) was safe and effective in the treatment of hypotension.7 In addition, a case report of massive air embolism during PCI demonstrated that IC epinephrine was successfully used in resuscitation.8 These studies are limited with their very small cohorts and do not compare IC vs. IV epinephrine in cardiac arrest resuscitation.

The current study aimed to bridge the literature gap and examine the outcomes of IC vs. IV routes for epinephrine administration during cardiac arrest.

Methods

Study population, inclusion, and exclusion criteria

This is a prospective multicentre observational study including all patients who experienced cardiac arrest in the cath lab before, during, or after an elective, emergency, diagnostic, or interventional cardiac catheterization procedure performed at two tertiary hospitals, Misr University for Science and Technology Hospital and AlShiekh Zayed Specialized Hospital in Cairo, Egypt in the period from January 2015 till July 2022. Patients were excluded if (a) <18 years and >89 years of age, (b) the cause of arrest was deemed to be non-cardiac, (c) they received epinephrine via dual routes or routes other than IC or IV, (d) lack of direct access to the coronary circulation through a coronary catheter, (e) they had a pre-existing DNR order, or (f) they were unable/refused to consent. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee Board of Misr University for Sciences and Technology Hospital in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study protocol in the cath lab

The study protocol was explained to all patients referred to the cath lab (or their surrogates). Patients received standard care for the planned procedure. In the event of a cardiac arrest in the cath lab, patients were resuscitated according to the Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS) guidelines.9 During cardiac resuscitation, if the coronary catheter was already engaging one of the coronary arteries, the patient would be enrolled in the study, and epinephrine would be given either through an IC route (1 mg epinephrine IV every 3–5 min)9 or a similar dose through an IV route, according to the physician's discretion. If the coronary catheter was not already engaged in one of the coronaries, then the patient would be excluded from the study and would receive IV epinephrine immediately to avoid any delay in ACLS. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics, as well as procedural details, were collected.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was survival to hospital discharge. Secondary outcomes included the rate of ROSC in the cath lab, time-to-ROSC, and favourable neurological outcome at hospital discharge defined as a modified Rankin Score (MRS) <3.10

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean and SD values and were compared using t-tests. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages and were compared using χ2 test. Statistically, significant results were defined as a P-value <0.05. All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS 25).

Results

Study population

Out of 8152 patients who underwent cardiac catheterization at both institutions during the study period, 198 patients experienced cardiac arrest in the cath lab, of whom 36 were eliminated as per the exclusion criteria. The remaining 162 patients (1.07%) had direct coronary access via catheter engagement and hence met our inclusion criteria. The mean age was 60.69 ± 9.61 years, and women represented 34.6% of the cohort. The indication for cardiac catheterization was stable angina in 10.5%, unstable angina in 20.4%, ST-elevation myocardial infarction in 35.2%, and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction in 32.1% of the cohort.

During resuscitation, 52 (32.1%) received IC epinephrine, and 110 (67.1%) received IV epinephrine. There was no difference in patients’ demographics and baseline characteristics between the two groups (Table1). The cumulative dose utilized to achieve ROSC was significantly lower in the IC vs. IV epinephrine group (1.17 ± 0.47 mg vs. 2.71 ± 1.67 mg, P < 0.001, respectively). Statistically, there were no significant differences regarding other procedural information (e.g. indication for coronary angiogram, elective vs. emergent, the number of vessels with obstructive disease, shockable vs. non-shockable rhythm during cardiac arrest, advanced airway insertion … etc.) between both groups (Table2).

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics in intravenous vs. intracoronary epinephrine cohorts

| . | Cohort . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics . | Intravenous epinephrine . | Intracoronary epinephrine . | P-value . |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 61.01 ± 9.27 | 60.06 ± 10.29 | 0.557 |

| Female, n (%) | 41 (37.27%) | 15 (28.85%) | 0.292 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 29.4 ± 3.1 | 30.4 ± 2.52 | 0.107 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 83 (75.45%) | 38 (73.08%) | 0.745 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 59 (53.64%) | 26 (50%) | 0.665 |

| Active smoking, n (%) | 49 (44.55%) | 26 (50%) | 0.516 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 56 (50.91%) | 23 (44.23%) | 0.427 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 9 (8.18%) | 4 (7.69%) | 0.915 |

| Asthma, n (%) | 2 (1.82%) | 1 (1.92%) | 0.963 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 24 (21.8%) | 10 (19.2%) | 0.706 |

| Chronic liver disease, n (%) | 1 (0.91%) | 3 (5.77%) | 0.063 |

| Prior stroke, n (%) | 11 (10%) | 5 (9.62%) | 0.939 |

| Prior coronary artery disease, n (%) | 51 (46.36%) | 29 (55.77%) | 0.264 |

| Prior myocardial infarction, n (%) | 3 (2.73%) | 2 (3.85%) | 0.701 |

| Prior coronary intervention, n (%) | 8 (7.27%) | 3 (5.77%) | 0.723 |

| Prior coronary artery bypass, n (%) | 5 (4.55%) | 3 (5.77%) | 0.737 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, mean ± SD | 50.9 ± 9.2 | 48.2 ± 13.1 | 0.132 |

| . | Cohort . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics . | Intravenous epinephrine . | Intracoronary epinephrine . | P-value . |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 61.01 ± 9.27 | 60.06 ± 10.29 | 0.557 |

| Female, n (%) | 41 (37.27%) | 15 (28.85%) | 0.292 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 29.4 ± 3.1 | 30.4 ± 2.52 | 0.107 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 83 (75.45%) | 38 (73.08%) | 0.745 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 59 (53.64%) | 26 (50%) | 0.665 |

| Active smoking, n (%) | 49 (44.55%) | 26 (50%) | 0.516 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 56 (50.91%) | 23 (44.23%) | 0.427 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 9 (8.18%) | 4 (7.69%) | 0.915 |

| Asthma, n (%) | 2 (1.82%) | 1 (1.92%) | 0.963 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 24 (21.8%) | 10 (19.2%) | 0.706 |

| Chronic liver disease, n (%) | 1 (0.91%) | 3 (5.77%) | 0.063 |

| Prior stroke, n (%) | 11 (10%) | 5 (9.62%) | 0.939 |

| Prior coronary artery disease, n (%) | 51 (46.36%) | 29 (55.77%) | 0.264 |

| Prior myocardial infarction, n (%) | 3 (2.73%) | 2 (3.85%) | 0.701 |

| Prior coronary intervention, n (%) | 8 (7.27%) | 3 (5.77%) | 0.723 |

| Prior coronary artery bypass, n (%) | 5 (4.55%) | 3 (5.77%) | 0.737 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, mean ± SD | 50.9 ± 9.2 | 48.2 ± 13.1 | 0.132 |

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics in intravenous vs. intracoronary epinephrine cohorts

| . | Cohort . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics . | Intravenous epinephrine . | Intracoronary epinephrine . | P-value . |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 61.01 ± 9.27 | 60.06 ± 10.29 | 0.557 |

| Female, n (%) | 41 (37.27%) | 15 (28.85%) | 0.292 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 29.4 ± 3.1 | 30.4 ± 2.52 | 0.107 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 83 (75.45%) | 38 (73.08%) | 0.745 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 59 (53.64%) | 26 (50%) | 0.665 |

| Active smoking, n (%) | 49 (44.55%) | 26 (50%) | 0.516 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 56 (50.91%) | 23 (44.23%) | 0.427 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 9 (8.18%) | 4 (7.69%) | 0.915 |

| Asthma, n (%) | 2 (1.82%) | 1 (1.92%) | 0.963 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 24 (21.8%) | 10 (19.2%) | 0.706 |

| Chronic liver disease, n (%) | 1 (0.91%) | 3 (5.77%) | 0.063 |

| Prior stroke, n (%) | 11 (10%) | 5 (9.62%) | 0.939 |

| Prior coronary artery disease, n (%) | 51 (46.36%) | 29 (55.77%) | 0.264 |

| Prior myocardial infarction, n (%) | 3 (2.73%) | 2 (3.85%) | 0.701 |

| Prior coronary intervention, n (%) | 8 (7.27%) | 3 (5.77%) | 0.723 |

| Prior coronary artery bypass, n (%) | 5 (4.55%) | 3 (5.77%) | 0.737 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, mean ± SD | 50.9 ± 9.2 | 48.2 ± 13.1 | 0.132 |

| . | Cohort . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics . | Intravenous epinephrine . | Intracoronary epinephrine . | P-value . |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 61.01 ± 9.27 | 60.06 ± 10.29 | 0.557 |

| Female, n (%) | 41 (37.27%) | 15 (28.85%) | 0.292 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 29.4 ± 3.1 | 30.4 ± 2.52 | 0.107 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 83 (75.45%) | 38 (73.08%) | 0.745 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 59 (53.64%) | 26 (50%) | 0.665 |

| Active smoking, n (%) | 49 (44.55%) | 26 (50%) | 0.516 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 56 (50.91%) | 23 (44.23%) | 0.427 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 9 (8.18%) | 4 (7.69%) | 0.915 |

| Asthma, n (%) | 2 (1.82%) | 1 (1.92%) | 0.963 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 24 (21.8%) | 10 (19.2%) | 0.706 |

| Chronic liver disease, n (%) | 1 (0.91%) | 3 (5.77%) | 0.063 |

| Prior stroke, n (%) | 11 (10%) | 5 (9.62%) | 0.939 |

| Prior coronary artery disease, n (%) | 51 (46.36%) | 29 (55.77%) | 0.264 |

| Prior myocardial infarction, n (%) | 3 (2.73%) | 2 (3.85%) | 0.701 |

| Prior coronary intervention, n (%) | 8 (7.27%) | 3 (5.77%) | 0.723 |

| Prior coronary artery bypass, n (%) | 5 (4.55%) | 3 (5.77%) | 0.737 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, mean ± SD | 50.9 ± 9.2 | 48.2 ± 13.1 | 0.132 |

Procedural characteristics in intravenous vs. intracoronary epinephrine cohorts

| . | Cohort . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics . | Intravenous epinephrine . | Intracoronary epinephrine . | P-value . |

| Clinical indication for coronary angiogram, n (%) | 0.586 | ||

| Stable angina | 12 (11%) | 5 (9.6%) | |

| Unstable angina | 24 (22%) | 9 (17.3%) | |

| ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 34 (31%) | 23 (44.2%) | |

| Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 38 (34%) | 14 (27%) | |

| Other (preoperative CA, etc.) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1.9%) | |

| Status of coronary angiogram, n (%) | 0.716 | ||

| Emergency | 72 (65.5%) | 37 (71.2%) | |

| Urgent | 25 (22.7%) | 9 (17.3%) | |

| Elective | 13 (11.8%) | 6 (11.5%) | |

| Number of vessels with obstructive disease, mean ± SD | 2.3 ± 1.12 | 2.12 ± 1.32 | 0.369 |

| Number of vessels intervened on, mean ± SD | 1.8 ± 0.61 | 1.65 ± 0.75 | 0.177 |

| Number of stents placed, mean ± SD | 2.16 ± 1.66 | 2.05 ± 1.59 | 0.690 |

| Vessel involved, n (%) | |||

| Left main coronary artery | 20 (18.2%) | 15 (28.8%) | 0.124 |

| Left anterior descending artery | 57 (51.8%) | 33 (63.5%) | 0.164 |

| Left circumflex artery | 35 (31.8%) | 10 (19.2%) | 0.095 |

| Right coronary artery | 31 (28.2%) | 10 (19.2%) | 0.221 |

| Shockable rhythm, n (%) | 45 (40.91%) | 21 (40.38%) | 0.949 |

| Advanced airway placement, n (%) | 68 (61.82%) | 24 (46.15%) | 0.06 |

| Total dose of epinephrine, mg, mean ± SD | 2.71 ± 1.67 | 1.17 ± 0.47 | <0.001 |

| . | Cohort . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics . | Intravenous epinephrine . | Intracoronary epinephrine . | P-value . |

| Clinical indication for coronary angiogram, n (%) | 0.586 | ||

| Stable angina | 12 (11%) | 5 (9.6%) | |

| Unstable angina | 24 (22%) | 9 (17.3%) | |

| ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 34 (31%) | 23 (44.2%) | |

| Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 38 (34%) | 14 (27%) | |

| Other (preoperative CA, etc.) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1.9%) | |

| Status of coronary angiogram, n (%) | 0.716 | ||

| Emergency | 72 (65.5%) | 37 (71.2%) | |

| Urgent | 25 (22.7%) | 9 (17.3%) | |

| Elective | 13 (11.8%) | 6 (11.5%) | |

| Number of vessels with obstructive disease, mean ± SD | 2.3 ± 1.12 | 2.12 ± 1.32 | 0.369 |

| Number of vessels intervened on, mean ± SD | 1.8 ± 0.61 | 1.65 ± 0.75 | 0.177 |

| Number of stents placed, mean ± SD | 2.16 ± 1.66 | 2.05 ± 1.59 | 0.690 |

| Vessel involved, n (%) | |||

| Left main coronary artery | 20 (18.2%) | 15 (28.8%) | 0.124 |

| Left anterior descending artery | 57 (51.8%) | 33 (63.5%) | 0.164 |

| Left circumflex artery | 35 (31.8%) | 10 (19.2%) | 0.095 |

| Right coronary artery | 31 (28.2%) | 10 (19.2%) | 0.221 |

| Shockable rhythm, n (%) | 45 (40.91%) | 21 (40.38%) | 0.949 |

| Advanced airway placement, n (%) | 68 (61.82%) | 24 (46.15%) | 0.06 |

| Total dose of epinephrine, mg, mean ± SD | 2.71 ± 1.67 | 1.17 ± 0.47 | <0.001 |

Procedural characteristics in intravenous vs. intracoronary epinephrine cohorts

| . | Cohort . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics . | Intravenous epinephrine . | Intracoronary epinephrine . | P-value . |

| Clinical indication for coronary angiogram, n (%) | 0.586 | ||

| Stable angina | 12 (11%) | 5 (9.6%) | |

| Unstable angina | 24 (22%) | 9 (17.3%) | |

| ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 34 (31%) | 23 (44.2%) | |

| Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 38 (34%) | 14 (27%) | |

| Other (preoperative CA, etc.) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1.9%) | |

| Status of coronary angiogram, n (%) | 0.716 | ||

| Emergency | 72 (65.5%) | 37 (71.2%) | |

| Urgent | 25 (22.7%) | 9 (17.3%) | |

| Elective | 13 (11.8%) | 6 (11.5%) | |

| Number of vessels with obstructive disease, mean ± SD | 2.3 ± 1.12 | 2.12 ± 1.32 | 0.369 |

| Number of vessels intervened on, mean ± SD | 1.8 ± 0.61 | 1.65 ± 0.75 | 0.177 |

| Number of stents placed, mean ± SD | 2.16 ± 1.66 | 2.05 ± 1.59 | 0.690 |

| Vessel involved, n (%) | |||

| Left main coronary artery | 20 (18.2%) | 15 (28.8%) | 0.124 |

| Left anterior descending artery | 57 (51.8%) | 33 (63.5%) | 0.164 |

| Left circumflex artery | 35 (31.8%) | 10 (19.2%) | 0.095 |

| Right coronary artery | 31 (28.2%) | 10 (19.2%) | 0.221 |

| Shockable rhythm, n (%) | 45 (40.91%) | 21 (40.38%) | 0.949 |

| Advanced airway placement, n (%) | 68 (61.82%) | 24 (46.15%) | 0.06 |

| Total dose of epinephrine, mg, mean ± SD | 2.71 ± 1.67 | 1.17 ± 0.47 | <0.001 |

| . | Cohort . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics . | Intravenous epinephrine . | Intracoronary epinephrine . | P-value . |

| Clinical indication for coronary angiogram, n (%) | 0.586 | ||

| Stable angina | 12 (11%) | 5 (9.6%) | |

| Unstable angina | 24 (22%) | 9 (17.3%) | |

| ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 34 (31%) | 23 (44.2%) | |

| Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 38 (34%) | 14 (27%) | |

| Other (preoperative CA, etc.) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1.9%) | |

| Status of coronary angiogram, n (%) | 0.716 | ||

| Emergency | 72 (65.5%) | 37 (71.2%) | |

| Urgent | 25 (22.7%) | 9 (17.3%) | |

| Elective | 13 (11.8%) | 6 (11.5%) | |

| Number of vessels with obstructive disease, mean ± SD | 2.3 ± 1.12 | 2.12 ± 1.32 | 0.369 |

| Number of vessels intervened on, mean ± SD | 1.8 ± 0.61 | 1.65 ± 0.75 | 0.177 |

| Number of stents placed, mean ± SD | 2.16 ± 1.66 | 2.05 ± 1.59 | 0.690 |

| Vessel involved, n (%) | |||

| Left main coronary artery | 20 (18.2%) | 15 (28.8%) | 0.124 |

| Left anterior descending artery | 57 (51.8%) | 33 (63.5%) | 0.164 |

| Left circumflex artery | 35 (31.8%) | 10 (19.2%) | 0.095 |

| Right coronary artery | 31 (28.2%) | 10 (19.2%) | 0.221 |

| Shockable rhythm, n (%) | 45 (40.91%) | 21 (40.38%) | 0.949 |

| Advanced airway placement, n (%) | 68 (61.82%) | 24 (46.15%) | 0.06 |

| Total dose of epinephrine, mg, mean ± SD | 2.71 ± 1.67 | 1.17 ± 0.47 | <0.001 |

| . | RR (95% CI) . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes . | Intravenous epinephrine . | Intracoronary epinephrine . | P-value . |

| Survival to discharge | 59 (53.64%) | 44 (84.62%) | <0.001 |

| Rate of rate of return of spontaneous circulation | 70 (63.64%) | 49 (94.23%) | <0.001 |

| Time to rate of return of spontaneous circulation, min, mean ± SD | 6.8 ± 2.11 | 2.6 ± 1.97 | <0.0001 |

| Favourable neurological recovery (modified Rankin Scale < 3) | 52 (47.27%) | 40 (76.92%) | <0.001 |

| . | RR (95% CI) . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes . | Intravenous epinephrine . | Intracoronary epinephrine . | P-value . |

| Survival to discharge | 59 (53.64%) | 44 (84.62%) | <0.001 |

| Rate of rate of return of spontaneous circulation | 70 (63.64%) | 49 (94.23%) | <0.001 |

| Time to rate of return of spontaneous circulation, min, mean ± SD | 6.8 ± 2.11 | 2.6 ± 1.97 | <0.0001 |

| Favourable neurological recovery (modified Rankin Scale < 3) | 52 (47.27%) | 40 (76.92%) | <0.001 |

| . | RR (95% CI) . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes . | Intravenous epinephrine . | Intracoronary epinephrine . | P-value . |

| Survival to discharge | 59 (53.64%) | 44 (84.62%) | <0.001 |

| Rate of rate of return of spontaneous circulation | 70 (63.64%) | 49 (94.23%) | <0.001 |

| Time to rate of return of spontaneous circulation, min, mean ± SD | 6.8 ± 2.11 | 2.6 ± 1.97 | <0.0001 |

| Favourable neurological recovery (modified Rankin Scale < 3) | 52 (47.27%) | 40 (76.92%) | <0.001 |

| . | RR (95% CI) . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes . | Intravenous epinephrine . | Intracoronary epinephrine . | P-value . |

| Survival to discharge | 59 (53.64%) | 44 (84.62%) | <0.001 |

| Rate of rate of return of spontaneous circulation | 70 (63.64%) | 49 (94.23%) | <0.001 |

| Time to rate of return of spontaneous circulation, min, mean ± SD | 6.8 ± 2.11 | 2.6 ± 1.97 | <0.0001 |

| Favourable neurological recovery (modified Rankin Scale < 3) | 52 (47.27%) | 40 (76.92%) | <0.001 |

Outcomes

Epinephrine administration via IC route during resuscitation was associated with higher survival to hospital discharge (84.62% vs. 53.64%, P < 0.001) compared with IV route. Similarly, the rate of ROSC was higher (94.23% vs. 63.64%, P < 0.001), and the time-to-ROSC was shorter (2.6 ± 1.97 min vs. 6.8 ± 2.11 min, P < 0.0001) in the IC vs. IV groups, respectively. In patients who survived, the rate of favourable neurological outcome (MRS < 3) at discharge was higher in the IC epinephrine group (76.92% vs. 47.27%, P < 0.001) compared with IV group (Figure 1 and Table3). No signs suggestive of epinephrine toxicity were observed throughout the hospital stay.

Discussion

Cardiac arrest in the cath lab is a serious, and often unavoidable, complication that is associated with poor outcomes. Capitalizing on the assets the facility has to offer such as invasive equipment and a trained interventional team may maximize the survival rate and improve clinical outcomes. Despite existing evidence of the efficacy and safety of lower dose epinephrine delivered IC for some cath lab complications such as no-reflow, no study has compared the clinical outcomes of IC vs. IV route for epinephrine in patients with cardiac arrest in the cath lab. The current study aimed to address this gap in the literature.

The current study showed important findings. First, survival to discharge was more likely to occur in patients who received IC epinephrine during cardiac arrest. Second, ROSC was more commonly achieved, and in lesser time, in patients who received IC vs. IV epinephrine. Third, in patients who survived, those who received IC epinephrine had better neurological outcomes likely related to faster achievement of ROSC during cardiac arrest. Finally, there were no serious side effects from IC epinephrine, and hence, this is the first-in-human study, to our knowledge, to show that it is safe and effective to deliver epinephrine IC at the same IV dose recommended by the ACLS guidelines.

Epinephrine is a sympathomimetic catecholamine known for its potent agonist effects on both alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptors. The alpha effects cause peripheral vasoconstriction, which in turn leads to increased coronary perfusion pressure.11 The higher rates of ROSC and shorter time-to-ROSC observed in this study could be attributed to the differences in the pharmacokinetics of epinephrine when administered by the IC vs. the IV routes, where epinephrine delivered via IC pathway is more likely to attain peak concentrations in a shorter time than via IV approach. This could be the underlying mechanism accounting for the differences in clinical outcomes between both groups. Our hypothesis is supported by the work of several researchers who demonstrated that the more proximal the site of infusion to the coronary circulation, the better the outcome. Researchers demonstrated that epinephrine delivered through the sternal intraosseous (IO) route attained higher peak concentrations in a shorter time than that delivered by the tibial IO route.12

Similarly, in their study on 114 patients, Schlundt et al.13 found that IC injection of adenosine resulted in identical fractional flow reserve measurements compared with the IV pathway infusion at a much smaller dose, requiring a shorter time. Furthermore, chest compressions performed during CPR may impede venous return and, consequently, drug concentration when administered intravenously.14

The faster ROSC achieved with IC pathway is likely to be the cause of reduced risk and duration of neurological injury. This was evident in this study by the superior survival to discharge and favourable neurological outcome upon discharge (defined as MRS < 3) in the IC group compared with IV.

Our study has multiple strengths. It is the first-in-human study to show the safety and efficacy of IC epinephrine in cardiac arrest. Additionally, it provides some evidence that the clinical outcome of cardiac arrest may be improved if it is feasible to administer epinephrine through IC rather than IV route. However, our study does not come without limitations. First, it is an observational study, and hence, confounding cannot be entirely excluded. One of the potential confounding factors is the physician's discretion regarding which route of epinephrine they chose. Unfortunately, due to the critical condition during cardiac arrest, we could not perform the study in a randomized fashion. Another potential confounding factor is the administration of IC epinephrine in a timely fashion. If the catheter was not already engaged in one of the coronary arteries, then an attempt to engage one of the coronaries during ACLS may lead to a delay in epinephrine administration. To mitigate this limitation, we prospectively designed our protocol to include only patients in whom coronary access was readily present. Patients without coronary access received IV epinephrine and were excluded from the study. Second, our study includes a small cohort. In addition, it is limited to two centres in one country and, hence, cannot be generalized to other ethnicities. Larger prospective randomized trials are needed to confirm our results.

Conclusions

In this prospective multicentre observational study, IC epinephrine during cardiac arrest in the cath lab may be associated with improved survival and outcomes compared with traditional IV epinephrine administration.

Funding

None

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.