-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Astrid Apor, Andrea Bartykowszki, Bálint Szilveszter, Andrea Varga, Ferenc I Suhai, Aristomenis Manouras, Levente Molnár, Ádám L Jermendy, Alexisz Panajotu, Mirjam Franciska Turáni, Roland Papp, Júlia Karády, Márton Kolossváry, Tímea Kováts, Pál Maurovich-Horvat, Béla Merkely, Anikó Ilona Nagy, Subclinical leaflet thrombosis after transcatheter aortic valve implantation is associated with silent brain injury on brain magnetic resonance imaging, European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Imaging, Volume 23, Issue 12, December 2022, Pages 1584–1595, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jeac191

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

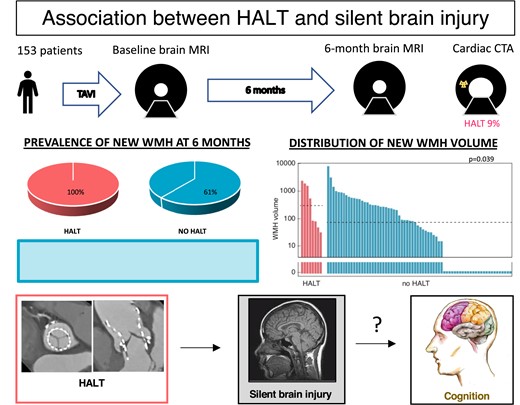

Whether hypoattenuated leaflet thickening (HALT) following transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) carries a risk of subclinical brain injury (SBI) is unknown. We investigated whether HALT is associated with SBI detected on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and whether post-TAVI SBI impacts the patients’ cognition and outcome.

We prospectively enrolled 153 patients (age: 78.1 ± 6.3 years; female 44%) who underwent TAVI. Brain MRI was performed shortly post-TAVI and 6 months later to assess the occurrence of acute silent cerebral ischaemic lesions (SCIL) and chronic white matter hyperintensities (WMH). HALT was screened by cardiac computed tomography (CT) angiography (CTA) 6 months post-TAVI. Neurocognitive evaluation was performed before, shortly after and 6 months following TAVI. At 6 months, 115 patients had diagnostic CTA and 10 had HALT. HALT status, baseline, and follow-up MRIs were available in 91 cases. At 6 months, new SCIL was evident in 16%, new WMH in 66%. New WMH was more frequent (100 vs. 62%; P = 0.047) with higher median volume (319 vs. 50 mm3; P = 0.039) among HALT-patients. In uni- and multivariate analysis, HALT was associated with new WMH volume (beta: 0.72; 95%CI: 0.2–1.39; P = 0.009). The patients’ cognitive trajectory from pre-TAVI to 6 months showed significant association with the 6-month SCIL volume (beta: −4.69; 95%CI: −9.13 to 0.27; P = 0.038), but was not related to the presence or volume of new WMH. During a 3.1-year follow-up, neither HALT [hazard ratio (HR): 0.86; 95%CI: 0.202–3.687; P = 0.84], nor the related WMH burden (HR: 1.09; 95%CI: 0.701–1.680; P = 0.71) was related with increased mortality.

At 6 months post-TAVI, HALT was linked with greater WMH burden, but did not carry an increased risk of cognitive decline or mortality over a 3.1-year follow-up (NCT02826200).

See the editorial comment for this article ‘Cognitive implications of subclinical leaflet thrombosis after transcatheter aortic valve implantation’, by P. van der Bijl and J. J. Bax, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jeac198.

Introduction

Hypoattenuated leaflet thickening (HALT) is a relatively common phenomenon after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), with a reported prevalence ranging between 10 and 40%1–4 depending on patient-, prosthesis-, and medication-related factors. In the majority of cases, HALT is a clinically silent phenomenon found in asymptomatic patients with normal valve gradients.4–6 Nonetheless, concerns remain regarding the potentially increased incidence of thromboembolic events in these patients. Conflicting evidence has been reported on the association between HALT and ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA).3,7–11 Importantly, whether the presence of HALT is associated with a higher risk of subclinical neurological complications has not been investigated.

The importance of silent brain injury (SBI), including acute silent cerebral ischaemic lesions (SCIL) transiently visible on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and chronic white matter hyperintensities (WMH) on fluid-attenuated inverse recovery sequence (FLAIR) is getting increasingly recognized in the context of cardiovascular diseases.12,13 Conditions that represent a high embolic burden, such as atrial fibrillation or carotid artery disease have been linked with SBI development.13

In the context of TAVI, procedure-related SCILs can be detected on the majority of post-TAVI brain MRI scans14–16 and have been associated with transient cognitive decline.14,16,17 The current body of evidence on cognitive outcomes after TAVI suggests that during medium-term follow-up cognitive function remains stable at the group-level.18 However, this might not hold true at the individual level; patients might experience various cognitive outcomes, including improvement, preservation, or deterioration. With the introduction of TAVI to a broader, younger population a deeper understanding of not only procedural but also long-term complications and prognosis is becoming paramount. In relation to this, identifying the predictive factors of cognitive decline or improvement is highly relevant.

We hypothesized that patients with HALT might be exposed to an increased risk of SBI, with potential impact on cognitive functioning. Thus, we set out to investigate whether the presence of HALT is associated with an increased risk of developing clinically silent cerebral lesions detected by MRI, and to assess how SBI (developing peri-procedurally or during follow-up) may impact the short- and medium-term cognitive trajectory of patients undergoing TAVI.

Methods

Study population and design

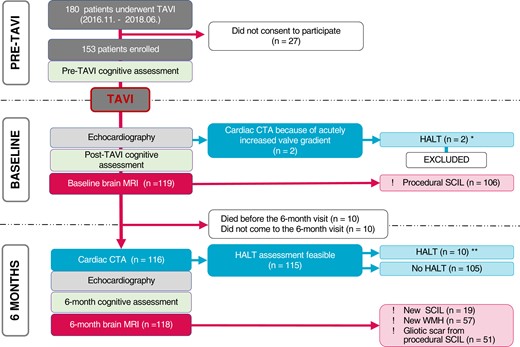

The RulE out Transcatheter aOrtic valve thRombosis with post Implantation Computed tomography (RETORIC) study was a prospective, single-centre, observational cohort study that enrolled all consecutive patients who underwent TAVI at the Semmelweis University Heart and Vascular Centre, Budapest, Hungary, between November 2016 and June 2018 and gave consent (NCT02826200). All patients received a self-expandable valve [CoreValve, EvolutR (both Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA), Portico (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA)]. Post-TAVI brain MRI was performed in all patients before hospital discharge unless contraindicated, to look for acute SCILs on DWI and document baseline WMH burden on FLAIR.

At 6 months post-TAVI, cardiac computed tomography (CT) angiography (CTA) was performed to screen for the presence of HALT in all patients unless contraindicated, as well as a repeat brain MRI. Cognitive assessment was performed pre-TAVI, post-TAVI before hospital discharge, and at 6 months after TAVI. A flowchart is provided in Figure 1 (see also Supplementary data online, Figure S1) The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee and all patients provided written informed consent for the procedures.

Study flow chart. CTA, computed tomography angiography; HALT, hypoattenuated leaflet thickening; SCIL, silent cerebral ischaemic lesion; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; WMH, white matter hyperintensity. *Two patients with acute HALT are included in the analysis of HALT predictors (12 patients altogether). **Only those with HALT detected at 6 months are included in the analysis of the consequences of HALT (10 patients).

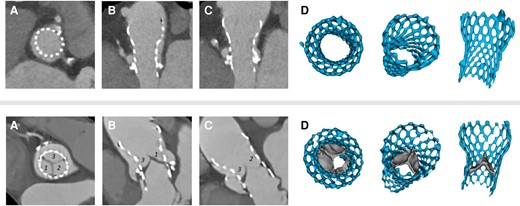

CT and HALT assessment

CTA was performed with retrospective electrocardiogram-gating using a 256-slice CT scanner (Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands). Images were reconstructed with 1 mm slice thickness and 1 mm increment using a hybrid iterative reconstruction (iDOSE4, Philips Healthcare, Cleveland, OH, USA) technique.

The presence of HALT was evaluated by three experienced radiologists blinded to echocardiographic and clinical parameters. All images were assessed by all three readers to achieve a consensus read. At end-diastole, each cusp was separately evaluated for the presence of leaflet thickening. In long-axis view, the thickness of each leaflet was measured in parallel and perpendicular axes to the frame. Based on both measurements an average thickness of <1 mm was considered as no HALT (0 point), 1–2 mm of hypoattenuated mass was considered as mild thickening (one point), 3–5 mm as moderate (two points), and >5 mm was considered as severe leaflet thickening (three points) (see Supplementary data online, Table S1). A summed score of 4 or more was considered HALT19,20 (Figure 2).

Representative CTA images of an aortic prosthesis without (upper panel) and with (lower panel) HALT. End diastolic, short axis (A), multiplanar (B and C), and 3D (D) reconstructions. Upper panel: the cusps of the prosthesis are basically nonvisible, representing normal prosthesis morphology without leaflet thickening. The summed leaflet score is 0 point. Lower panel: Cusps 1 and 3 have moderate leaflet thickening (2–2 points), Cusp 2 has mild leaflet thickening affecting the margin of the leaflet (one point). The summed leaflet score is five points. CTA, computed tomography angiography; HALT, hypoattenuated leaflet thickening; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Brain MRI

Brain MRI was performed on a 1.5 T scanner (Achieva1.5, Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands) using an eight-channel head coil. The protocol included diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) (with automatically generated DWI and apparent diffusion coefficient maps) and FLAIR (see Supplementary data online, Table S2). Two experienced radiologists, blinded to clinical and other imaging data, read all MRIs in consensus using a picture archiving and communication system workstation (IMPAX 6.5.2, AGFA Healthcare, Mortsel, Belgium). The volume of all DWI+ lesions (hyperintensity on DWI, corresponding hypointensity on ADC) and that of new FLAIR hyperintense lesions at 6 months were recorded. The lesion volume was calculated as follows: lesion territory from manual segmentation × slice thickness (mm3). To determine WMH volumes on the baseline-MRI we used the lesion segmentation tool [toolbox (version 3.0.0) for Statistical Parametric Mapping].21

The following parameters were assessed at baseline:

The presence and volume of acute DWI+ ischaemic lesions (procedural SCIL).

White matter hyperintense lesion (baseline WMH) volume.

The following parameters were assessed at 6 months:

The presence and volume of DWI+ acute ischaemic lesions (6-month new SCIL).

The presence and volume of new WMH lesions that were not visible on the baseline scan (6-month new WMH), including gliotic scars of DWI+ lesions on the baseline-MRI.

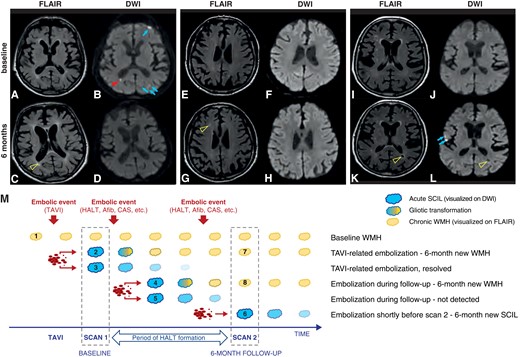

Silent brain lesions

The detection of acute ischaemic injury (SCIL) was based on DWI MRI and we used fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images for visualization of chronic lesions (WMH). SCILs can be detected within minutes after the onset of ischaemia with DWI; however, the specific signal changes persist only for about 14 days.22 Therefore, DWI enables the identification of procedural embolic lesions even in the absence of a pre-operative scan, however, has limited utility for determining embolic prevalence. Acute infarcts might resolve without trace or undergo gliotic scarring eventually resulting in chronic lesions (WMH) that are visible on FLAIR.

White matter hyperintensities (WMHs) represent chronic ischaemic injury; WMH volume provides information about cumulative ischaemic burden. WMHs are visualized on FLAIR, which in contrast to DWI, turn positive in delay, but persists indefinitely, so we could detect the new chronic lesions on the 6-month MRI, which were not present at baseline (Figure 3).

(A–L) Brain MRI images representing the various lesions analysed. (A–D) Procedural SCILs in multiple territories on DWI (B), which disappeared during follow-up without leaving permanent cerebral lesions (arrows), and one small periventricular SCIL (arrowhead) that evolved into gliotic scar on the 6-month MRI FLAIR image (C, open arrowhead). (E–H) New WMH on the 6-month MRI FLAIR image (G, open arrowhead), without restricted diffusion on DWI (H) that was not present at baseline on the FLAIR (E) or DWI images (F). (I–L) New lesions on the 6-month MRI that were not present at baseline. (K and L) 6-month new SCILs (L, arrows) that were not present at baseline (J); 6-month new chronic ischaemic lesion (WMH) on the FLAIR image (K, open arrowhead) with central signal intensity similar to fluid on DWI (L, open arrowhead). (M) Schematic representation of the evolution of silent brain injury. SCAN 1, performed within 5 days after TAVI, provides information both about the patients’ pre-procedural chronic ischaemic burden (Lesion 1, pre-existing WMH), and about the procedure-related embolic load (DWI+ SCILs, Lesions 2 and 3). DWI+ lesions might resolve without trace (Lesion 3) or transform into a chronic lesion (Lesion 2) later visible as a new WMH on FLAIR (Lesion 7). SCAN 2, performed 6 months post-TAVI, detects as SCIL any recent ischaemic lesions that occurred within 14 days of the SCAN (Lesion 6). Also, it detects as new WMH (i.e. WMH that was not visible on the baseline scan, Lesions 7 and 8) any lesions that occurred any time during follow-up and turned into WMH (Lesion 4). On the other hand, it would miss those lesions that occurred during follow-up and resolved by the time of SCAN 2 (Lesion 5). AFib, atrial fibrillation; CAS, carotid artery stenosis; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; SCIL, silent cerebral ischaemic lesion; WMH, white matter hyperintensity.

Echocardiography

All patients underwent transthoracic echocardiography examination before TAVI, post-TAVI before discharge, and 6 months after TAVI.

Neurocognitive assessment

All subjects underwent a standardized cognitive assessment using a repeatable Hungarian version of the Addenbrookes Cognitive Assessment (ACE) test,23 performed by one of two trained investigators, blinded to CTA and MRI data, pre-TAVI (0–3 days), post-TAVI before hospital discharge (3–7 days), and 6 months following TAVI.

Endpoint definition

The primary endpoint of this study was imaging evidence of any potentially embolization related SBI on the 6-month brain MRI including:

the presence and volume of DWI+ acute ischaemic lesions (6-month new SCIL) or

the presence and volume of new WMH at 6 months.

Further endpoints were: 1, clinically overt stroke/TIA during the first 6 months post-TAVI; 2, total ACE score change between baseline and 6 months (6-month ΔACE); 3, all-cause death.

Six patients suffered clinically overt procedural stroke. They were excluded from all analyses that involved SBIs.

Mortality data were obtained from the National Health Insurance Fund provided official death records, ensuring that no patient was lost to follow-up. Follow-up for survival started at the 6-month visit.

Statistical analysis

To assess the normality of data, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used. Continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile ranges as appropriate; categorical variables are presented as frequencies with percentages.

For comparison between groups, continuous variables were tested using the unpaired Student’s t-test in case of a normal distribution and the Mann–Whitney U test if the assumption of a normal distribution was rejected. Differences in ACE scores at different time points were compared using a paired Student’s t-test. Differences in categorical variables were tested by using the Fisher’s exact or the Pearson’s χ2 test. To determine whether HALT is associated with MRI endpoints or neurocognitive outcomes uni- and multivariate linear regression analyses were performed. In the univariate analyses, parameters with expected predictive value (based on former studies and clinical evidence) were selected by the study team. Parameters with a P-value <0.05 in the univariate analysis were included into the multivariate model.

Uni- and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to generate hazard ratios. For survival analysis, variables with a P-value ≤ 0.1 in univariate analysis were included into the multivariate regression and HALT was introduced as a forced variable.

Because of the limited patient number, in the univariate analyses all individuals with available data were included, whereas the multivariable models included patients with available data for all tested parameters.

A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All calculations were performed using R software (SPSS version 25; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

For more methodical details see the Supplementary data online.

Results

Patient population and study flow

We enrolled 153 patients (age 78.1 ± 6.3 years; female 44%). Pre-TAVI cognitive examination was performed in 106 patients. Shortly post-TAVI [median 4 (3; 5) days], 119 patients underwent brain MRI. Post-TAVI cognitive assessment was completed in 83 patients.

At the 6-month follow-up, 131 patients were examined. Echocardiography was performed in 129, cardiac CTA in 116, control brain MRI in 118, and neurocognitive examination in 93 cases. Full datasets of baseline and follow-up MRI and CTA examinations were available in 91 patients (Figure 1).

Prevalence and predictors of HALT

Two patients developed acute and clinically apparent valve thrombosis (i.e. HALT with increased valve gradients) shortly after TAVI, before hospital discharge. No overt neurological events were detected in these patients. They were excluded from further analysis.

At the 6-month examination, HALT was detected in 10 patients (8.7%). Characteristics of the study population, stratified by the presence of HALT are summarized in Table 1. Patients with HALT were less likely to be on oral anticoagulant therapy (8 vs. 45%, P = 0.012). HALT was more frequent in Portico valves, but this difference was not statistically significant (Evolute: 8.3%, CoreValve: 0%, Protico: 20%; P = 0.17). The groups were similar regarding other pre-TAVI and peri-procedural characteristics.

Patient characteristics of the entire study cohort and stratified according to the presence of HALT

| . | All patients (153)∗ . | Without HALT (105) . | With HALT (12) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 78.1 ± 6.3 | 78.4 ± 6.3 | 77.7 ± 4.4 | 0.74 |

| Female (n; %) | 67/153 (44) | 40/105 (38) | 8/12 (67) | 0.07 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.1 ± 5.6 | 28.6 ± 5.7 | 25.6 ± 3.7 | 0.07 |

| Hypertension (n; %) | 140/153 (92) | 93/105 (89) | 11/12 (92) | 0.99 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n; %) | 74/153 (48) | 49/105 (47) | 5/12 (42) | 0.77 |

| Dyslipidaemia (n; %) | 101/153 (66) | 67/105 (64) | 7/12 (58) | 0.76 |

| Peripheral artery disease (n; %) | 120/153 (78) | 51/105 (49) | 7/12 (58) | 0.56 |

| COPD (n; %) | 32/153 (21) | 20/105 (19) | 3/12 (27) | 0.70 |

| Atrial fibrillation (n; %) | 62/153 (41) | 39/105 (37) | 3/12 (27) | 0.99 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 5.0 ± 1.5 | 4.7 ± 1.5 | 5.3 ± 1.4 | 0.20 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 96.9 ± 33.5 | 91.5 ± 27.7 | 88.8 ± 23.2 | 0.75 |

| Pre-TAVI EF (%) | 52.5 ± 13.0 | 53.3 ± 12.8 | 46.9 ± 14.5 | 0.08 |

| Pre-TAVI NYHA class | ||||

| NYHA II (n; %) | 74/153 (48) | 52/105 (50) | 5/12 (42) | 0.77 |

| NYHA III (n; %) | 71/153 (46) | 47/105 (45) | 5/12 (42) | 0.99 |

| NYAH IV (n; %) | 8/153 (5) | 6/105 (6) | 2/12 (17) | 0.19 |

| Procedural characteristics | ||||

| Valve in valve TAVI (n; %) | 6/153 (4) | 6/105 (6) | 0/12 (0) | 0.99 |

| TAVI type | ||||

| CoreValve (n; %) | 14/153 (9) | 8/105 (8) | 0/12 (0) | 0.99 |

| Evolut (n; %) | 107/153 (70) | 77/105 (78) | 7/12 (58) | 0.32 |

| Portico (n; %) | 32/153 (21) | 20/105 (19) | 5/12 (42) | 0.13 |

| Annulus minimal diameter (mm) | 20.4 ± 2.8 | 20.4 ± 3.0 | 20.6 ± 1.6 | 0.80 |

| Annulus maximal diameter (mm) | 24.5 ± 3.1 | 24.5 ± 3.3 | 24.7 ± 1.2 | 0.83 |

| Access route | ||||

| Femoral (n; %) | 143/153 (93) | 100/105 (95) | 11/12 (92) | 0.49 |

| Subclavian (n; %) | 8/153 (5) | 5/105 (5) | 0/12 (0) | 0.99 |

| Carotid (n; %) | 2/153 (1) | 0/105 (0) | 1/12 (1) | 0.11 |

| Pre-dilation (n; %) | 10/153 (7) | 4/105 (4) | 2/12 (17) | 0.12 |

| Post-dilation (n; %) | 111/153 (73) | 72/105 (69) | 10/12 (83) | 0.51 |

| Peri-procedural stroke (n; %) | 6/153 (4) | 3/105 (3) | 0/12 (0) | 0.99 |

| Post-TAVI antithrombotic therapy | ||||

| SAPT (n; %) | 18/133 (14) | 12/105 (11) | 3/12 (25) | 0.18 |

| DAPT (n; %) | 57/133 (43) | 43/105 (41) | 8/12 (73) | 0.13 |

| OAC (n; %) | 58/133 (44) | 50/105 (45) | 1/12 (8) | 0.012 |

| OAC alone (n; %) | 23/133 (17) | 20/105 (19) | 0/12 (0) | 0.22 |

| OAC + SAPT (n; %) | 35/133 (26) | 30/105 (29) | 1/12 (17) | 0.18 |

| . | All patients (153)∗ . | Without HALT (105) . | With HALT (12) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 78.1 ± 6.3 | 78.4 ± 6.3 | 77.7 ± 4.4 | 0.74 |

| Female (n; %) | 67/153 (44) | 40/105 (38) | 8/12 (67) | 0.07 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.1 ± 5.6 | 28.6 ± 5.7 | 25.6 ± 3.7 | 0.07 |

| Hypertension (n; %) | 140/153 (92) | 93/105 (89) | 11/12 (92) | 0.99 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n; %) | 74/153 (48) | 49/105 (47) | 5/12 (42) | 0.77 |

| Dyslipidaemia (n; %) | 101/153 (66) | 67/105 (64) | 7/12 (58) | 0.76 |

| Peripheral artery disease (n; %) | 120/153 (78) | 51/105 (49) | 7/12 (58) | 0.56 |

| COPD (n; %) | 32/153 (21) | 20/105 (19) | 3/12 (27) | 0.70 |

| Atrial fibrillation (n; %) | 62/153 (41) | 39/105 (37) | 3/12 (27) | 0.99 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 5.0 ± 1.5 | 4.7 ± 1.5 | 5.3 ± 1.4 | 0.20 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 96.9 ± 33.5 | 91.5 ± 27.7 | 88.8 ± 23.2 | 0.75 |

| Pre-TAVI EF (%) | 52.5 ± 13.0 | 53.3 ± 12.8 | 46.9 ± 14.5 | 0.08 |

| Pre-TAVI NYHA class | ||||

| NYHA II (n; %) | 74/153 (48) | 52/105 (50) | 5/12 (42) | 0.77 |

| NYHA III (n; %) | 71/153 (46) | 47/105 (45) | 5/12 (42) | 0.99 |

| NYAH IV (n; %) | 8/153 (5) | 6/105 (6) | 2/12 (17) | 0.19 |

| Procedural characteristics | ||||

| Valve in valve TAVI (n; %) | 6/153 (4) | 6/105 (6) | 0/12 (0) | 0.99 |

| TAVI type | ||||

| CoreValve (n; %) | 14/153 (9) | 8/105 (8) | 0/12 (0) | 0.99 |

| Evolut (n; %) | 107/153 (70) | 77/105 (78) | 7/12 (58) | 0.32 |

| Portico (n; %) | 32/153 (21) | 20/105 (19) | 5/12 (42) | 0.13 |

| Annulus minimal diameter (mm) | 20.4 ± 2.8 | 20.4 ± 3.0 | 20.6 ± 1.6 | 0.80 |

| Annulus maximal diameter (mm) | 24.5 ± 3.1 | 24.5 ± 3.3 | 24.7 ± 1.2 | 0.83 |

| Access route | ||||

| Femoral (n; %) | 143/153 (93) | 100/105 (95) | 11/12 (92) | 0.49 |

| Subclavian (n; %) | 8/153 (5) | 5/105 (5) | 0/12 (0) | 0.99 |

| Carotid (n; %) | 2/153 (1) | 0/105 (0) | 1/12 (1) | 0.11 |

| Pre-dilation (n; %) | 10/153 (7) | 4/105 (4) | 2/12 (17) | 0.12 |

| Post-dilation (n; %) | 111/153 (73) | 72/105 (69) | 10/12 (83) | 0.51 |

| Peri-procedural stroke (n; %) | 6/153 (4) | 3/105 (3) | 0/12 (0) | 0.99 |

| Post-TAVI antithrombotic therapy | ||||

| SAPT (n; %) | 18/133 (14) | 12/105 (11) | 3/12 (25) | 0.18 |

| DAPT (n; %) | 57/133 (43) | 43/105 (41) | 8/12 (73) | 0.13 |

| OAC (n; %) | 58/133 (44) | 50/105 (45) | 1/12 (8) | 0.012 |

| OAC alone (n; %) | 23/133 (17) | 20/105 (19) | 0/12 (0) | 0.22 |

| OAC + SAPT (n; %) | 35/133 (26) | 30/105 (29) | 1/12 (17) | 0.18 |

HALT, hypoattenuated leaflet thickening; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NYHA; New York Heart Association functional class; EF, ejection fraction; SAPT/DAPT, single/dual antiplatelet therapy (without OAC); OAC, oral anticoagulant (including OAC alone and OAC + SAPT).

Of the enrolled 153 patients, HALT status was available only in 117 cases. In order to present potential risk factors for developing HALT, in Table 1 all patients diagnosed with HALT at any time during the study (i.e. two acute HALT cases and 10 patients with HALT on the 6-month CTA) are included in the HALT group. Regarding post-TAVI antithrombotic therapy, 131 patients who came for the 6-month follow-up and the two acute HALT cases are included in the total cohort (n = 133).

Patient characteristics of the entire study cohort and stratified according to the presence of HALT

| . | All patients (153)∗ . | Without HALT (105) . | With HALT (12) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 78.1 ± 6.3 | 78.4 ± 6.3 | 77.7 ± 4.4 | 0.74 |

| Female (n; %) | 67/153 (44) | 40/105 (38) | 8/12 (67) | 0.07 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.1 ± 5.6 | 28.6 ± 5.7 | 25.6 ± 3.7 | 0.07 |

| Hypertension (n; %) | 140/153 (92) | 93/105 (89) | 11/12 (92) | 0.99 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n; %) | 74/153 (48) | 49/105 (47) | 5/12 (42) | 0.77 |

| Dyslipidaemia (n; %) | 101/153 (66) | 67/105 (64) | 7/12 (58) | 0.76 |

| Peripheral artery disease (n; %) | 120/153 (78) | 51/105 (49) | 7/12 (58) | 0.56 |

| COPD (n; %) | 32/153 (21) | 20/105 (19) | 3/12 (27) | 0.70 |

| Atrial fibrillation (n; %) | 62/153 (41) | 39/105 (37) | 3/12 (27) | 0.99 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 5.0 ± 1.5 | 4.7 ± 1.5 | 5.3 ± 1.4 | 0.20 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 96.9 ± 33.5 | 91.5 ± 27.7 | 88.8 ± 23.2 | 0.75 |

| Pre-TAVI EF (%) | 52.5 ± 13.0 | 53.3 ± 12.8 | 46.9 ± 14.5 | 0.08 |

| Pre-TAVI NYHA class | ||||

| NYHA II (n; %) | 74/153 (48) | 52/105 (50) | 5/12 (42) | 0.77 |

| NYHA III (n; %) | 71/153 (46) | 47/105 (45) | 5/12 (42) | 0.99 |

| NYAH IV (n; %) | 8/153 (5) | 6/105 (6) | 2/12 (17) | 0.19 |

| Procedural characteristics | ||||

| Valve in valve TAVI (n; %) | 6/153 (4) | 6/105 (6) | 0/12 (0) | 0.99 |

| TAVI type | ||||

| CoreValve (n; %) | 14/153 (9) | 8/105 (8) | 0/12 (0) | 0.99 |

| Evolut (n; %) | 107/153 (70) | 77/105 (78) | 7/12 (58) | 0.32 |

| Portico (n; %) | 32/153 (21) | 20/105 (19) | 5/12 (42) | 0.13 |

| Annulus minimal diameter (mm) | 20.4 ± 2.8 | 20.4 ± 3.0 | 20.6 ± 1.6 | 0.80 |

| Annulus maximal diameter (mm) | 24.5 ± 3.1 | 24.5 ± 3.3 | 24.7 ± 1.2 | 0.83 |

| Access route | ||||

| Femoral (n; %) | 143/153 (93) | 100/105 (95) | 11/12 (92) | 0.49 |

| Subclavian (n; %) | 8/153 (5) | 5/105 (5) | 0/12 (0) | 0.99 |

| Carotid (n; %) | 2/153 (1) | 0/105 (0) | 1/12 (1) | 0.11 |

| Pre-dilation (n; %) | 10/153 (7) | 4/105 (4) | 2/12 (17) | 0.12 |

| Post-dilation (n; %) | 111/153 (73) | 72/105 (69) | 10/12 (83) | 0.51 |

| Peri-procedural stroke (n; %) | 6/153 (4) | 3/105 (3) | 0/12 (0) | 0.99 |

| Post-TAVI antithrombotic therapy | ||||

| SAPT (n; %) | 18/133 (14) | 12/105 (11) | 3/12 (25) | 0.18 |

| DAPT (n; %) | 57/133 (43) | 43/105 (41) | 8/12 (73) | 0.13 |

| OAC (n; %) | 58/133 (44) | 50/105 (45) | 1/12 (8) | 0.012 |

| OAC alone (n; %) | 23/133 (17) | 20/105 (19) | 0/12 (0) | 0.22 |

| OAC + SAPT (n; %) | 35/133 (26) | 30/105 (29) | 1/12 (17) | 0.18 |

| . | All patients (153)∗ . | Without HALT (105) . | With HALT (12) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 78.1 ± 6.3 | 78.4 ± 6.3 | 77.7 ± 4.4 | 0.74 |

| Female (n; %) | 67/153 (44) | 40/105 (38) | 8/12 (67) | 0.07 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.1 ± 5.6 | 28.6 ± 5.7 | 25.6 ± 3.7 | 0.07 |

| Hypertension (n; %) | 140/153 (92) | 93/105 (89) | 11/12 (92) | 0.99 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n; %) | 74/153 (48) | 49/105 (47) | 5/12 (42) | 0.77 |

| Dyslipidaemia (n; %) | 101/153 (66) | 67/105 (64) | 7/12 (58) | 0.76 |

| Peripheral artery disease (n; %) | 120/153 (78) | 51/105 (49) | 7/12 (58) | 0.56 |

| COPD (n; %) | 32/153 (21) | 20/105 (19) | 3/12 (27) | 0.70 |

| Atrial fibrillation (n; %) | 62/153 (41) | 39/105 (37) | 3/12 (27) | 0.99 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 5.0 ± 1.5 | 4.7 ± 1.5 | 5.3 ± 1.4 | 0.20 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 96.9 ± 33.5 | 91.5 ± 27.7 | 88.8 ± 23.2 | 0.75 |

| Pre-TAVI EF (%) | 52.5 ± 13.0 | 53.3 ± 12.8 | 46.9 ± 14.5 | 0.08 |

| Pre-TAVI NYHA class | ||||

| NYHA II (n; %) | 74/153 (48) | 52/105 (50) | 5/12 (42) | 0.77 |

| NYHA III (n; %) | 71/153 (46) | 47/105 (45) | 5/12 (42) | 0.99 |

| NYAH IV (n; %) | 8/153 (5) | 6/105 (6) | 2/12 (17) | 0.19 |

| Procedural characteristics | ||||

| Valve in valve TAVI (n; %) | 6/153 (4) | 6/105 (6) | 0/12 (0) | 0.99 |

| TAVI type | ||||

| CoreValve (n; %) | 14/153 (9) | 8/105 (8) | 0/12 (0) | 0.99 |

| Evolut (n; %) | 107/153 (70) | 77/105 (78) | 7/12 (58) | 0.32 |

| Portico (n; %) | 32/153 (21) | 20/105 (19) | 5/12 (42) | 0.13 |

| Annulus minimal diameter (mm) | 20.4 ± 2.8 | 20.4 ± 3.0 | 20.6 ± 1.6 | 0.80 |

| Annulus maximal diameter (mm) | 24.5 ± 3.1 | 24.5 ± 3.3 | 24.7 ± 1.2 | 0.83 |

| Access route | ||||

| Femoral (n; %) | 143/153 (93) | 100/105 (95) | 11/12 (92) | 0.49 |

| Subclavian (n; %) | 8/153 (5) | 5/105 (5) | 0/12 (0) | 0.99 |

| Carotid (n; %) | 2/153 (1) | 0/105 (0) | 1/12 (1) | 0.11 |

| Pre-dilation (n; %) | 10/153 (7) | 4/105 (4) | 2/12 (17) | 0.12 |

| Post-dilation (n; %) | 111/153 (73) | 72/105 (69) | 10/12 (83) | 0.51 |

| Peri-procedural stroke (n; %) | 6/153 (4) | 3/105 (3) | 0/12 (0) | 0.99 |

| Post-TAVI antithrombotic therapy | ||||

| SAPT (n; %) | 18/133 (14) | 12/105 (11) | 3/12 (25) | 0.18 |

| DAPT (n; %) | 57/133 (43) | 43/105 (41) | 8/12 (73) | 0.13 |

| OAC (n; %) | 58/133 (44) | 50/105 (45) | 1/12 (8) | 0.012 |

| OAC alone (n; %) | 23/133 (17) | 20/105 (19) | 0/12 (0) | 0.22 |

| OAC + SAPT (n; %) | 35/133 (26) | 30/105 (29) | 1/12 (17) | 0.18 |

HALT, hypoattenuated leaflet thickening; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NYHA; New York Heart Association functional class; EF, ejection fraction; SAPT/DAPT, single/dual antiplatelet therapy (without OAC); OAC, oral anticoagulant (including OAC alone and OAC + SAPT).

Of the enrolled 153 patients, HALT status was available only in 117 cases. In order to present potential risk factors for developing HALT, in Table 1 all patients diagnosed with HALT at any time during the study (i.e. two acute HALT cases and 10 patients with HALT on the 6-month CTA) are included in the HALT group. Regarding post-TAVI antithrombotic therapy, 131 patients who came for the 6-month follow-up and the two acute HALT cases are included in the total cohort (n = 133).

MRI findings

At baseline, procedural SCIL was detected in 106 patients (91%) [median lesion number: 6 (2; 10), median lesion volume: 222 (87; 590) mm3]. The median baseline WMH volume was 19 701 (8238; 29 995) mm3.

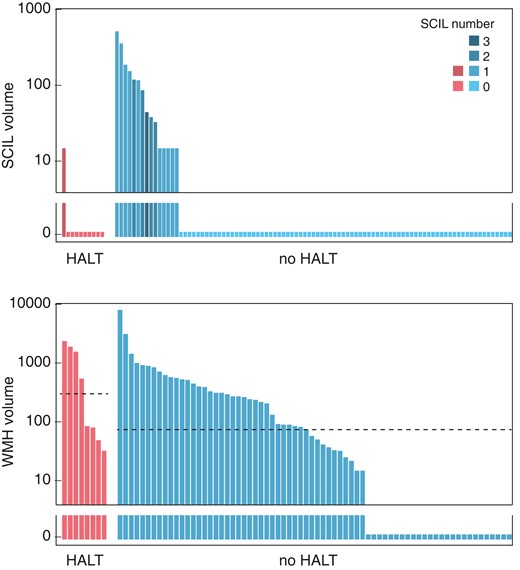

At 6 months, new SCILs were present in 16% of the patients, with similar distribution among patients with and without HALT (Figure 4). WMH volume increase was detected in 57 patients [median volume 58 (0; 322) mm3]. New WMH appeared more frequently (100 vs. 62%, P = 0.047) and the median new WMH volume was larger (319 vs. 50 mm3, P = 0.039) in patients with HALT (Table 2).

Distribution of SCIL and new WMH on the 6-month MRI among patients with and without HALT, as indicated below the panels. The y-axis is logarithmic and zero values are shown below the axis break. Upper panel: SCIL distribution. Lower panel: WMH distribution. Horizontal dashed lines indicate the median volumes in each group. The median is zero for both groups on Panel A. HALT, hypoattenuated leaflet thickening; SCIL, silent cerebral ischaemic lesion; WMH, white matter hyperintensity.

Follow-up clinical and imaging data of the entire study population and stratified according to the presence of HALT

| . | All patients (131) . | Without HALT (105) . | With HALT (10) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiography | ||||

| 6-month aortic Vmax (m/s) | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 0.58 |

| (129) | (103) | (10) | ||

| 6-month AMG (mmHg) | 8.5 ± 5.5 | 8.5 ± 5.8 | 8.7 ± 4.6 | 0.93 |

| (129) | (103) | (10) | ||

| 6-Month brain MRI | ||||

| New SCIL on 6-month MRI (n; %) | 19/118 (16) | 15/93 (16) | 1/10 (10) | 0.99 |

| 6-month new SCIL volume [mm3, median (IQR)] | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | 0.71 |

| 6-month new SCIL volume (mm3, mean ± SD) | 17 ± 68 | 19 ± 71 | 2 ± 5 | 0.71 |

| New WMH on the 6-month MRI (n; %) | 57/87 (66) | 43/69 (62) | 8/8 (100) | 0.047 |

| 6-month new WMH volume [mm3, median (IQR)] | 58 (0; 322) | 50 (0; 312) | 319 (72; 1656) | 0.039 |

| Neurocognitive outcomes | ||||

| TIA/stroke/systemic embolization (n; %) | 2a/131 (2) | 2/106 (2) | 0/10 (0) | 0.99 |

| Pre-TAVI ACE score | 72.2 ± 12.3 | 73.2 ± 12.6 | 78.8 ± 12.7 | 0.40 |

| (106) | (71) | (5) | ||

| 6-month ACE score | 73.7 ± 12.9 | 74.6 ± 12.4 | 75.8 ± 15.6 | 0.84 |

| (93) | (76) | (5) | ||

| 6-month ΔACE | 1.3 ± 8.5 | 1.0 ± 8.5 | −3.5 ± 6.4 | 0.46 |

| (73) | (61) | (2) |

| . | All patients (131) . | Without HALT (105) . | With HALT (10) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiography | ||||

| 6-month aortic Vmax (m/s) | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 0.58 |

| (129) | (103) | (10) | ||

| 6-month AMG (mmHg) | 8.5 ± 5.5 | 8.5 ± 5.8 | 8.7 ± 4.6 | 0.93 |

| (129) | (103) | (10) | ||

| 6-Month brain MRI | ||||

| New SCIL on 6-month MRI (n; %) | 19/118 (16) | 15/93 (16) | 1/10 (10) | 0.99 |

| 6-month new SCIL volume [mm3, median (IQR)] | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | 0.71 |

| 6-month new SCIL volume (mm3, mean ± SD) | 17 ± 68 | 19 ± 71 | 2 ± 5 | 0.71 |

| New WMH on the 6-month MRI (n; %) | 57/87 (66) | 43/69 (62) | 8/8 (100) | 0.047 |

| 6-month new WMH volume [mm3, median (IQR)] | 58 (0; 322) | 50 (0; 312) | 319 (72; 1656) | 0.039 |

| Neurocognitive outcomes | ||||

| TIA/stroke/systemic embolization (n; %) | 2a/131 (2) | 2/106 (2) | 0/10 (0) | 0.99 |

| Pre-TAVI ACE score | 72.2 ± 12.3 | 73.2 ± 12.6 | 78.8 ± 12.7 | 0.40 |

| (106) | (71) | (5) | ||

| 6-month ACE score | 73.7 ± 12.9 | 74.6 ± 12.4 | 75.8 ± 15.6 | 0.84 |

| (93) | (76) | (5) | ||

| 6-month ΔACE | 1.3 ± 8.5 | 1.0 ± 8.5 | −3.5 ± 6.4 | 0.46 |

| (73) | (61) | (2) |

TIA in both cases. AMG, aortic mean gradient; SCIL, silent cerebral ischaemic lesion; WMH, white matter hyperintensity; ACE, Addenbrookes Cognitive Examination; TIA, transient ischaemic attack; 6-month ΔACE, ACE score change between pre-TAVI and 6 months. 6-Month new WMH volume is presented as median values, followed by interquartile ranges in brackets, as well as mean value and standard deviation. As Table 2 is to present the consequences of HALT, patients who were HALT positive at the time of the 6-month follow-up are included in the HALT group (i.e. the two patients with acute valve thrombosis are not included in these analyses). Numbers in brackets indicate the number of patients with available data.

Follow-up clinical and imaging data of the entire study population and stratified according to the presence of HALT

| . | All patients (131) . | Without HALT (105) . | With HALT (10) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiography | ||||

| 6-month aortic Vmax (m/s) | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 0.58 |

| (129) | (103) | (10) | ||

| 6-month AMG (mmHg) | 8.5 ± 5.5 | 8.5 ± 5.8 | 8.7 ± 4.6 | 0.93 |

| (129) | (103) | (10) | ||

| 6-Month brain MRI | ||||

| New SCIL on 6-month MRI (n; %) | 19/118 (16) | 15/93 (16) | 1/10 (10) | 0.99 |

| 6-month new SCIL volume [mm3, median (IQR)] | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | 0.71 |

| 6-month new SCIL volume (mm3, mean ± SD) | 17 ± 68 | 19 ± 71 | 2 ± 5 | 0.71 |

| New WMH on the 6-month MRI (n; %) | 57/87 (66) | 43/69 (62) | 8/8 (100) | 0.047 |

| 6-month new WMH volume [mm3, median (IQR)] | 58 (0; 322) | 50 (0; 312) | 319 (72; 1656) | 0.039 |

| Neurocognitive outcomes | ||||

| TIA/stroke/systemic embolization (n; %) | 2a/131 (2) | 2/106 (2) | 0/10 (0) | 0.99 |

| Pre-TAVI ACE score | 72.2 ± 12.3 | 73.2 ± 12.6 | 78.8 ± 12.7 | 0.40 |

| (106) | (71) | (5) | ||

| 6-month ACE score | 73.7 ± 12.9 | 74.6 ± 12.4 | 75.8 ± 15.6 | 0.84 |

| (93) | (76) | (5) | ||

| 6-month ΔACE | 1.3 ± 8.5 | 1.0 ± 8.5 | −3.5 ± 6.4 | 0.46 |

| (73) | (61) | (2) |

| . | All patients (131) . | Without HALT (105) . | With HALT (10) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiography | ||||

| 6-month aortic Vmax (m/s) | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 0.58 |

| (129) | (103) | (10) | ||

| 6-month AMG (mmHg) | 8.5 ± 5.5 | 8.5 ± 5.8 | 8.7 ± 4.6 | 0.93 |

| (129) | (103) | (10) | ||

| 6-Month brain MRI | ||||

| New SCIL on 6-month MRI (n; %) | 19/118 (16) | 15/93 (16) | 1/10 (10) | 0.99 |

| 6-month new SCIL volume [mm3, median (IQR)] | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | 0.71 |

| 6-month new SCIL volume (mm3, mean ± SD) | 17 ± 68 | 19 ± 71 | 2 ± 5 | 0.71 |

| New WMH on the 6-month MRI (n; %) | 57/87 (66) | 43/69 (62) | 8/8 (100) | 0.047 |

| 6-month new WMH volume [mm3, median (IQR)] | 58 (0; 322) | 50 (0; 312) | 319 (72; 1656) | 0.039 |

| Neurocognitive outcomes | ||||

| TIA/stroke/systemic embolization (n; %) | 2a/131 (2) | 2/106 (2) | 0/10 (0) | 0.99 |

| Pre-TAVI ACE score | 72.2 ± 12.3 | 73.2 ± 12.6 | 78.8 ± 12.7 | 0.40 |

| (106) | (71) | (5) | ||

| 6-month ACE score | 73.7 ± 12.9 | 74.6 ± 12.4 | 75.8 ± 15.6 | 0.84 |

| (93) | (76) | (5) | ||

| 6-month ΔACE | 1.3 ± 8.5 | 1.0 ± 8.5 | −3.5 ± 6.4 | 0.46 |

| (73) | (61) | (2) |

TIA in both cases. AMG, aortic mean gradient; SCIL, silent cerebral ischaemic lesion; WMH, white matter hyperintensity; ACE, Addenbrookes Cognitive Examination; TIA, transient ischaemic attack; 6-month ΔACE, ACE score change between pre-TAVI and 6 months. 6-Month new WMH volume is presented as median values, followed by interquartile ranges in brackets, as well as mean value and standard deviation. As Table 2 is to present the consequences of HALT, patients who were HALT positive at the time of the 6-month follow-up are included in the HALT group (i.e. the two patients with acute valve thrombosis are not included in these analyses). Numbers in brackets indicate the number of patients with available data.

In 61% of the patients procedural SCILs underwent gliotic scar formation and were visible on the 6-month MRI; the rest disappeared without remnants.

Association between MRI findings and HALT

In univariate regression analysis, we found no interaction between HALT and the presence or volume of new SCIL on the 6-month MRI. On the other hand, HALT showed significant association with the volume of new WMH (beta: 0.69; 95%CI: 0.08–1.32; P = 0.028).

Atrial fibrillation is an established risk factor for SBI. Interestingly, we found no interaction between the presence of atrial fibrillation and the presence or volume of new cerebral lesions. One plausible explanation for that is that patients with atrial fibrillation were on efficient stroke prevention therapy. On the other hand, the CHA2DS2-VASc score represents a cumulative sum index of embolic risk, without in itself triggering anticoagulant medication. In search of potential other determinants of the patients’ silent embolic burden, we tested whether the observed SBIs were related to the CHA2DS2-VASc score. Indeed, the 6-month new SCIL volume was significantly associated with the CHA2DS2-VASc score (beta: 0.05; 95%CI: 0.001–0.09; P = 0.047), whereas in case of new WMH no such interaction was found.

Procedural SCIL contributes to WMH progression. Accordingly procedural SCIL volume showed strong association with the WMH volume increase (beta: 0.7; 95%CI: 0.53–0.89; P < 0.001). In multivariable analysis including HALT and procedural SCIL volume, both parameters remained significant determinants of the new WMH volume (Table 3).

| . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Beta . | 95%CI . | P . | Beta . | 95%CI . | P . |

| 6-month new SCIL volume | ||||||

| HALT | −0.11 | −0.37–0.14 | 0.38 | |||

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 0.05 | 0.00–0.09 | 0.047 | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.08 | −0.07–0.23 | 0.27 | |||

| 6-month new WMH volume | ||||||

| HALT | 0.69 | 0.08–1.32 | 0.028 | 0.79 | 0.20–1.39 | 0.009 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 0.09 | −0.03–0.21 | 0.16 | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.15 | −0.03–0.34 | 0.11 | |||

| Procedural SCIL volume | 0.71 | 0.53–0.89 | <0.001 | 0.58 | 0.18–1.00 | <0.001 |

| . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Beta . | 95%CI . | P . | Beta . | 95%CI . | P . |

| 6-month new SCIL volume | ||||||

| HALT | −0.11 | −0.37–0.14 | 0.38 | |||

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 0.05 | 0.00–0.09 | 0.047 | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.08 | −0.07–0.23 | 0.27 | |||

| 6-month new WMH volume | ||||||

| HALT | 0.69 | 0.08–1.32 | 0.028 | 0.79 | 0.20–1.39 | 0.009 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 0.09 | −0.03–0.21 | 0.16 | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.15 | −0.03–0.34 | 0.11 | |||

| Procedural SCIL volume | 0.71 | 0.53–0.89 | <0.001 | 0.58 | 0.18–1.00 | <0.001 |

HALT, hypoattenuated leaflet thickening; 6-month SCIL, silent cerebral ischaemic lesion on the 6-month MRI; 6-month new WMH, white matter hyperintensity on the 6-month MRI that was not visible at baseline.

| . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Beta . | 95%CI . | P . | Beta . | 95%CI . | P . |

| 6-month new SCIL volume | ||||||

| HALT | −0.11 | −0.37–0.14 | 0.38 | |||

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 0.05 | 0.00–0.09 | 0.047 | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.08 | −0.07–0.23 | 0.27 | |||

| 6-month new WMH volume | ||||||

| HALT | 0.69 | 0.08–1.32 | 0.028 | 0.79 | 0.20–1.39 | 0.009 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 0.09 | −0.03–0.21 | 0.16 | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.15 | −0.03–0.34 | 0.11 | |||

| Procedural SCIL volume | 0.71 | 0.53–0.89 | <0.001 | 0.58 | 0.18–1.00 | <0.001 |

| . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Beta . | 95%CI . | P . | Beta . | 95%CI . | P . |

| 6-month new SCIL volume | ||||||

| HALT | −0.11 | −0.37–0.14 | 0.38 | |||

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 0.05 | 0.00–0.09 | 0.047 | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.08 | −0.07–0.23 | 0.27 | |||

| 6-month new WMH volume | ||||||

| HALT | 0.69 | 0.08–1.32 | 0.028 | 0.79 | 0.20–1.39 | 0.009 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 0.09 | −0.03–0.21 | 0.16 | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.15 | −0.03–0.34 | 0.11 | |||

| Procedural SCIL volume | 0.71 | 0.53–0.89 | <0.001 | 0.58 | 0.18–1.00 | <0.001 |

HALT, hypoattenuated leaflet thickening; 6-month SCIL, silent cerebral ischaemic lesion on the 6-month MRI; 6-month new WMH, white matter hyperintensity on the 6-month MRI that was not visible at baseline.

Cognitive trajectory and its determinants

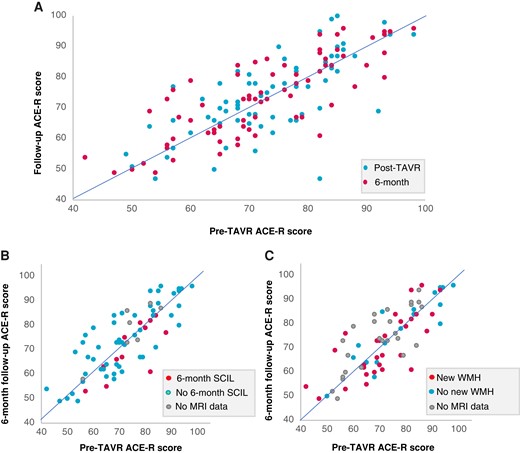

The overall cognitive performance of the cohort was stable over the follow-up period, with mean pre-operative, postoperative, and 6-month ACE scores of 72.2 ± 12.3, 74.1 ± 13.3, and 73.7 ± 12.9, respectively (P > 0.05 for all) (Table 2). Individual cognitive trajectories are displayed in Figure 5.

Cognitive trajectory of individual patients post-TAVI. (A) Cognitive trajectory of all patients with available cognitive data. Blue dots indicate ACE score change from pre-TAVI to soon after TAVI; red dots indicate ACE score change from pre-TAVI to the 6-month follow-up. (B and C) ACE score change from pre-TAVI to the 6-month follow-up stratified according to the presence (red) or absence (blue) of SCIL (B) or new WMH (C) on the 6-month MRI. Grey dots indicate patients without MRI data. TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve replacement; ACE, Addenbrookes Cognitive Examination; SCIL, silent cerebral ischaemic lesion; WMH, white matter hyperintensity.

The pre-TAVI ACE score in univariate analysis was associated with the patients’ age, educational level, CHA2DS2-VASC score, pre-operative aortic valve area, and baseline WMH volume. In multivariate analysis, only age and educational level remained significant predictors.

The pre-TAVI to 6 months ACE score change (6-month ΔACE) showed significant negative association with the 6-month SCIL volume, in contrast, it was not related with the 6-month new WMH volume. We found no association of the 6-month ΔACE with the procedural SCIL volume, or with the presence of gliotic remnants of these lesions on the 6-month MRI either. Additionally, there was a significant inverse association between the 6-month ΔACE and the pre-TAVI ACE score, i.e. patients with worse pre-TAVI scores showed the largest improvement 6 months post-TAVI (Table 4).

Cerebrovascular events and mortality

Between the implantation and 6-month visit, no strokes and two TIAs occurred, both in patients without HALT. Among the 131 patients, who showed up at the 6-month follow-up visit, 115 had HALT information. During a median follow-up period of 3.1 (2.6; 3.5) years, all together 32 death events occurred, 25 among those who had known HALT status. The all-cause mortality was similar in patients with and without HALT (6.2 vs. 7.3 deaths per 100 patient years, respectively).

In univariate Cox regression analysis, HALT was not associated with adverse outcome [P = 0.84, hazard ratio (HR): 0.86, 95%CI 0.2–3.7] (Table 5). Regarding brain imaging outcomes, the presence or volume of baseline or 6-month SCIL was not predictive of mortality, neither was the presence or volume of 6-month new WMH. However, in the multivariate model, the presence of gliotic scars on the 6-month MRI from peri-procedural SCILs was significantly associated with increased mortality (P = 0.010, HR: 7.8, 95%CI 1.633–37.260), together with atrial fibrillation and previous myocardial infarction (Table 5).

Predictors of the patients’ baseline cognitive performance and cognitive trajectory

| . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Beta . | 95%CI . | P . | Beta . | 95%CI . | P . |

| Pre-TAVI ACE score | ||||||

| Age | −0.56 | −0.88 to −0.88 | <0.001 | −0.81 | −1.34 to −0.27 | <0.001 |

| Years of education | 1.41 | 0.87–1.95 | <0.001 | 1.88 | 1.10–2.65 | <0.001 |

| Pre-TAVI AVA | 18.56 | 4.84–32.29 | 0.009 | |||

| CHA2DS2-VASc | −1.66 | −3.10 to −0.23 | 0.023 | |||

| Baseline WMH volume | −7.95 | −14.72 to −1.18 | 0.022 | |||

| 6-month ΔACE | ||||||

| Age | 0.40 | −0.43 to 0.18 | 0.40 | |||

| Years of education | 0.01 | −0.50 to 0.53 | 0.96 | |||

| Pre-TAVI AVA | −2.88 | −15.45 to 9.70 | 0.65 | |||

| CHA2DS2-VASc | −0.37 | −1.57 to 0.83 | 0.54 | |||

| Baseline WMH volume | −0.82 | −5.73 to 4.09 | 0.74 | |||

| Procedural SCIL volume | −0.39 | −3.54 to 2.75 | 0.80 | |||

| Pre-TAVI ACE score | −0.19 | −0.35 to −0.05 | 0.011 | −0.18 | −0.34 to −0.03 | 0.024 |

| 6-Month new WMH volume | 0.18 | −2.76 to 3.12 | 0.90 | |||

| 6-Month SCIL volume | −4.69 | −9.13 to −0.27 | 0.038 | −4.44 | −8.73 to −0.16 | 0.042 |

| Gliotic scar of procedural SCIL | −0.23 | −5.51 to 5.06 | 0.93 | |||

| . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Beta . | 95%CI . | P . | Beta . | 95%CI . | P . |

| Pre-TAVI ACE score | ||||||

| Age | −0.56 | −0.88 to −0.88 | <0.001 | −0.81 | −1.34 to −0.27 | <0.001 |

| Years of education | 1.41 | 0.87–1.95 | <0.001 | 1.88 | 1.10–2.65 | <0.001 |

| Pre-TAVI AVA | 18.56 | 4.84–32.29 | 0.009 | |||

| CHA2DS2-VASc | −1.66 | −3.10 to −0.23 | 0.023 | |||

| Baseline WMH volume | −7.95 | −14.72 to −1.18 | 0.022 | |||

| 6-month ΔACE | ||||||

| Age | 0.40 | −0.43 to 0.18 | 0.40 | |||

| Years of education | 0.01 | −0.50 to 0.53 | 0.96 | |||

| Pre-TAVI AVA | −2.88 | −15.45 to 9.70 | 0.65 | |||

| CHA2DS2-VASc | −0.37 | −1.57 to 0.83 | 0.54 | |||

| Baseline WMH volume | −0.82 | −5.73 to 4.09 | 0.74 | |||

| Procedural SCIL volume | −0.39 | −3.54 to 2.75 | 0.80 | |||

| Pre-TAVI ACE score | −0.19 | −0.35 to −0.05 | 0.011 | −0.18 | −0.34 to −0.03 | 0.024 |

| 6-Month new WMH volume | 0.18 | −2.76 to 3.12 | 0.90 | |||

| 6-Month SCIL volume | −4.69 | −9.13 to −0.27 | 0.038 | −4.44 | −8.73 to −0.16 | 0.042 |

| Gliotic scar of procedural SCIL | −0.23 | −5.51 to 5.06 | 0.93 | |||

ACE, Addenbrookes Cognitive Examination; AVA, aortic valve area; SCIL, silent cerebral ischaemic lesion; WMH, white matter hyperintensity; 6-month ΔACE, ACE score change between pre-TAVI and the 6-month follow-up.

Predictors of the patients’ baseline cognitive performance and cognitive trajectory

| . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Beta . | 95%CI . | P . | Beta . | 95%CI . | P . |

| Pre-TAVI ACE score | ||||||

| Age | −0.56 | −0.88 to −0.88 | <0.001 | −0.81 | −1.34 to −0.27 | <0.001 |

| Years of education | 1.41 | 0.87–1.95 | <0.001 | 1.88 | 1.10–2.65 | <0.001 |

| Pre-TAVI AVA | 18.56 | 4.84–32.29 | 0.009 | |||

| CHA2DS2-VASc | −1.66 | −3.10 to −0.23 | 0.023 | |||

| Baseline WMH volume | −7.95 | −14.72 to −1.18 | 0.022 | |||

| 6-month ΔACE | ||||||

| Age | 0.40 | −0.43 to 0.18 | 0.40 | |||

| Years of education | 0.01 | −0.50 to 0.53 | 0.96 | |||

| Pre-TAVI AVA | −2.88 | −15.45 to 9.70 | 0.65 | |||

| CHA2DS2-VASc | −0.37 | −1.57 to 0.83 | 0.54 | |||

| Baseline WMH volume | −0.82 | −5.73 to 4.09 | 0.74 | |||

| Procedural SCIL volume | −0.39 | −3.54 to 2.75 | 0.80 | |||

| Pre-TAVI ACE score | −0.19 | −0.35 to −0.05 | 0.011 | −0.18 | −0.34 to −0.03 | 0.024 |

| 6-Month new WMH volume | 0.18 | −2.76 to 3.12 | 0.90 | |||

| 6-Month SCIL volume | −4.69 | −9.13 to −0.27 | 0.038 | −4.44 | −8.73 to −0.16 | 0.042 |

| Gliotic scar of procedural SCIL | −0.23 | −5.51 to 5.06 | 0.93 | |||

| . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Beta . | 95%CI . | P . | Beta . | 95%CI . | P . |

| Pre-TAVI ACE score | ||||||

| Age | −0.56 | −0.88 to −0.88 | <0.001 | −0.81 | −1.34 to −0.27 | <0.001 |

| Years of education | 1.41 | 0.87–1.95 | <0.001 | 1.88 | 1.10–2.65 | <0.001 |

| Pre-TAVI AVA | 18.56 | 4.84–32.29 | 0.009 | |||

| CHA2DS2-VASc | −1.66 | −3.10 to −0.23 | 0.023 | |||

| Baseline WMH volume | −7.95 | −14.72 to −1.18 | 0.022 | |||

| 6-month ΔACE | ||||||

| Age | 0.40 | −0.43 to 0.18 | 0.40 | |||

| Years of education | 0.01 | −0.50 to 0.53 | 0.96 | |||

| Pre-TAVI AVA | −2.88 | −15.45 to 9.70 | 0.65 | |||

| CHA2DS2-VASc | −0.37 | −1.57 to 0.83 | 0.54 | |||

| Baseline WMH volume | −0.82 | −5.73 to 4.09 | 0.74 | |||

| Procedural SCIL volume | −0.39 | −3.54 to 2.75 | 0.80 | |||

| Pre-TAVI ACE score | −0.19 | −0.35 to −0.05 | 0.011 | −0.18 | −0.34 to −0.03 | 0.024 |

| 6-Month new WMH volume | 0.18 | −2.76 to 3.12 | 0.90 | |||

| 6-Month SCIL volume | −4.69 | −9.13 to −0.27 | 0.038 | −4.44 | −8.73 to −0.16 | 0.042 |

| Gliotic scar of procedural SCIL | −0.23 | −5.51 to 5.06 | 0.93 | |||

ACE, Addenbrookes Cognitive Examination; AVA, aortic valve area; SCIL, silent cerebral ischaemic lesion; WMH, white matter hyperintensity; 6-month ΔACE, ACE score change between pre-TAVI and the 6-month follow-up.

Cox proportional hazard univariate and multivariate model analysis for the prediction of overall mortality and to define the independent risk factors for mortality

| . | Univariate . | . | Multivariate . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | HR . | 95%CI . | P . | HR . | 95%CI . | P . |

| Age | 1.007 | 0.955–1.063 | 0.73 | |||

| Male gender | 1.177 | 0.581–2.387 | 0.65 | |||

| Ejection fraction | 1.007 | 0.98–1.035 | 0.60 | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.882 | 0.94–3.768 | 0.07 | 3.736 | 1.244–11.221 | 0.019 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 1.856 | 0.889–3.876 | 0.10 | 5.371 | 1.794–16.080 | 0.003 |

| HALT | 0.863 | 0.202–3.687 | 0.84 | 0.485 | 0.026–1.903 | 0.17 |

| Baseline WMH volume | 2.244 | 0.724–6.957 | 0.16 | |||

| Procedural SCIL volume | 1.013 | 0.584–1.756 | 0.96 | |||

| Gliotic transformation of procedural SCIL | 3.424 | 0.983–11.932 | 0.05 | 7.801 | 1.633–37.260 | 0.010 |

| 6-month SCIL volume | 1.101 | 0.43–2.821 | 0.84 | |||

| 6-month new WMH volume | 1.085 | 0.701–1.680 | 0.71 | |||

| . | Univariate . | . | Multivariate . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | HR . | 95%CI . | P . | HR . | 95%CI . | P . |

| Age | 1.007 | 0.955–1.063 | 0.73 | |||

| Male gender | 1.177 | 0.581–2.387 | 0.65 | |||

| Ejection fraction | 1.007 | 0.98–1.035 | 0.60 | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.882 | 0.94–3.768 | 0.07 | 3.736 | 1.244–11.221 | 0.019 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 1.856 | 0.889–3.876 | 0.10 | 5.371 | 1.794–16.080 | 0.003 |

| HALT | 0.863 | 0.202–3.687 | 0.84 | 0.485 | 0.026–1.903 | 0.17 |

| Baseline WMH volume | 2.244 | 0.724–6.957 | 0.16 | |||

| Procedural SCIL volume | 1.013 | 0.584–1.756 | 0.96 | |||

| Gliotic transformation of procedural SCIL | 3.424 | 0.983–11.932 | 0.05 | 7.801 | 1.633–37.260 | 0.010 |

| 6-month SCIL volume | 1.101 | 0.43–2.821 | 0.84 | |||

| 6-month new WMH volume | 1.085 | 0.701–1.680 | 0.71 | |||

HALT, hypoattenuated leaflet thickening; SCIL, silent cerebral ischaemic lesion; WMH, white matter hyperintensity.

Cox proportional hazard univariate and multivariate model analysis for the prediction of overall mortality and to define the independent risk factors for mortality

| . | Univariate . | . | Multivariate . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | HR . | 95%CI . | P . | HR . | 95%CI . | P . |

| Age | 1.007 | 0.955–1.063 | 0.73 | |||

| Male gender | 1.177 | 0.581–2.387 | 0.65 | |||

| Ejection fraction | 1.007 | 0.98–1.035 | 0.60 | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.882 | 0.94–3.768 | 0.07 | 3.736 | 1.244–11.221 | 0.019 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 1.856 | 0.889–3.876 | 0.10 | 5.371 | 1.794–16.080 | 0.003 |

| HALT | 0.863 | 0.202–3.687 | 0.84 | 0.485 | 0.026–1.903 | 0.17 |

| Baseline WMH volume | 2.244 | 0.724–6.957 | 0.16 | |||

| Procedural SCIL volume | 1.013 | 0.584–1.756 | 0.96 | |||

| Gliotic transformation of procedural SCIL | 3.424 | 0.983–11.932 | 0.05 | 7.801 | 1.633–37.260 | 0.010 |

| 6-month SCIL volume | 1.101 | 0.43–2.821 | 0.84 | |||

| 6-month new WMH volume | 1.085 | 0.701–1.680 | 0.71 | |||

| . | Univariate . | . | Multivariate . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | HR . | 95%CI . | P . | HR . | 95%CI . | P . |

| Age | 1.007 | 0.955–1.063 | 0.73 | |||

| Male gender | 1.177 | 0.581–2.387 | 0.65 | |||

| Ejection fraction | 1.007 | 0.98–1.035 | 0.60 | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.882 | 0.94–3.768 | 0.07 | 3.736 | 1.244–11.221 | 0.019 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 1.856 | 0.889–3.876 | 0.10 | 5.371 | 1.794–16.080 | 0.003 |

| HALT | 0.863 | 0.202–3.687 | 0.84 | 0.485 | 0.026–1.903 | 0.17 |

| Baseline WMH volume | 2.244 | 0.724–6.957 | 0.16 | |||

| Procedural SCIL volume | 1.013 | 0.584–1.756 | 0.96 | |||

| Gliotic transformation of procedural SCIL | 3.424 | 0.983–11.932 | 0.05 | 7.801 | 1.633–37.260 | 0.010 |

| 6-month SCIL volume | 1.101 | 0.43–2.821 | 0.84 | |||

| 6-month new WMH volume | 1.085 | 0.701–1.680 | 0.71 | |||

HALT, hypoattenuated leaflet thickening; SCIL, silent cerebral ischaemic lesion; WMH, white matter hyperintensity.

Discussion

This is the first study, which investigated the subclinical neurological consequences of HALT following TAVI. The main results of our study are the following: 1, Recent SCILs and new WMH were demonstrated in 16 and 66% of the patients, respectively, 6 months post-TAVI. 2, HALT was not linked with the presence or volume of 6-month SCIL, but it was associated with a higher rate of new WMH and larger new WMH volumes as compared with patients without HALT. 3, Increased WM lesion burden did not translate into measurable cognitive decline over a 6-month follow-up.

HALT and its potential implications

TAVI has brought a paradigm shift in the treatment of aortic stenosis. Over the past decades, with technical developments and accumulating operator experience procedural complication rates have decreased significantly and TAVI is now considered a safe and durable treatment of severe aortic stenosis.

HALT is a relatively recently identified complication of TAVI that remains incompletely understood. It can cause increased valve gradients and lead to early valve degeneration. Accordingly, current guidelines recommend considering oral anticoagulant treatment in such cases.24 Nonetheless, most patients with HALT display normal valve gradients and the clinical significance of subclinical leaflet thrombosis detected only on CTA remains uncertain. Of note, in a very recent large-scale study involving over 600 TAVI patients, Garcia et al.25 reported increased mortality associated with HALT, independent of valve gradients, which alerts to the potential risks of HALT that are not related to structural valve deterioration. Another concern regarding HALT is that it represents a potential source of systemic embolization. Following the landmark trial of Makkar et al.,11 where this phenomenon was first described and linked to an increased risk of cerebrovascular events, HALT has rapidly become the focus of attention in cardiovascular research. Although some subsequent studies confirmed the initial concerns,3,8,26 others failed to demonstrate increased rates of stroke or TIA in patients with HALT.4,5,20,27,28 Thus, based on current evidence, clinical outcomes in patients with HALT are generally considered benign without increased risk of neurological complications.

However, the spectrum of cerebrovascular injury extends beyond symptomatic neurologic events. It is now understood that clinically overt events represent only the tip of the iceberg with silent microembolizations and their potential cognitive consequences hiding beneath the surface. It is well documented, that SCILs and WMHs that also appear during the course of normal ageing, are highly prevalent in conditions carrying increased embolic risk, such as atrial fibrillation or carotid artery disease.12,29 Although termed clinically silent, both types of lesions have been linked with progressive cognitive decline, psychological changes, and dementia.12,13,29 Conceivably, HALT representing a potential source of repetitive microembolization carries the risk of SBI. With TAVI being increasingly used in progressively lower risk and younger patient populations, the appreciation of such risk becomes paramount.

The association of HALT with SBI

We found no association between HALT and the presence or volume of DWI+ recent SCIL at 6 months, whereas the CHA2DS2-VASc score was significantly related to the 6-month SCIL volume, underlining the importance of comorbidities in the development of these lesions. In contrast, WMH progression, reflecting the cumulative brain injury, was significantly associated with HALT, corroborating the theory that HALT might represent a source of chronic silent embolization leading to brain damage. The presence of HALT was screened 6 months after TAVI. HALT is notably a dynamic phenomenon, thus in some cases transient development and subsequent spontaneous resolution of HALT prior the time of 6-month CTA might have happened. Also, a significant proportion of SCILs, especially those of small size, tend to resolve without detectable remnants on later MRI scans. These considerations provide a plausible explanation, why WMH progression is a more sensitive marker of HALT-related SBI than SCIL, the latter transient signal reflecting only recent ischaemic events, which might resolve without trace. Thus, in the context of SCIL, the relatively lower impact signal of HALT might be disguised by the ‘noise’ of more robust embolic sources.

The short- and long-term impact of TAVI on cognitive performance

Since the high prevalence of SBI occurring in relation to the TAVI procedure became evident, considerable research has been devoted to the cognitive trajectory of patients following TAVI, mainly concentrating on the impact of peri-procedural SCIL on cognitive functioning.

In the present study, on the 6-month MRI new SCIL was detected in 16% of the cohort. Of note, the 6-month SCIL volume had a significant negative association with the patients’ cognitive trajectory from pre-TAVI to 6 months. This is concordant with the finding of Ghanem et al.14 that in contrast to the neutral effect of procedural lesions on long-term cognitive performance, patients with subacute SCILs had a trend towards persisting cognitive decline.

Although the negative impact of WMH accumulation on cognition is established, in our study we did not see such association. This might be explained by the limited follow-up time. Previous studies showed that WMH progression predicts cognitive impairment in a very early phase, i.e. cognitive decline may become evident years after the detection of WMH volume increase.14,30 Also, one can anticipate that the numerous positive effects of aortic valve replacement, including improved cerebral perfusion, better mobility, and generally improved quality of life of the patients might well outweigh the potential harm caused by WMH accumulation, at least in the examined time frame.

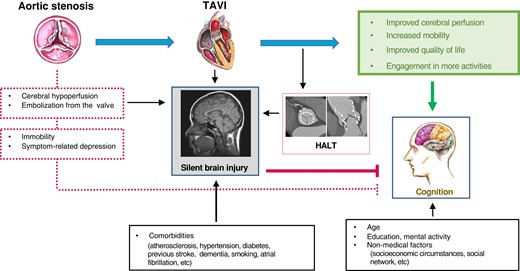

Despite the extensive literature on cognitive outcomes after TAVI, many questions remain open, highlighting the great complexity of post-TAVI cognitive evolution determined by the intricate interplay among positive and harmful impacts of patient- and procedure-related factors. Based on our results, HALT is one of these many factors entering into the equation through its association with WMH progression (Figure 6). The clinical relevance of potential subtle cognitive decline that might be associated with these lesions on the longer run appears limited in very elderly patients with numerous comorbidities; however, it might not be negligible when expanding TAVI to younger, healthier individuals.

Complex interplay among the positive and negative consequences of TAVI on the patients’ cognitive functioning. For details see the main text. TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; HALT, hypoattenuated leaflet thickening.

Limitations

The study cohort was of limited size, and especially the number of HALT cases is low, however, regarding the trial’s complex prospective design with systematically performed CTA and repeated brain MRI exams in asymptomatic patients, along with detailed clinical characterization and serial neurocognitive assessment, our study is still among the largest of its kind. Due to the limited cohort size, our results might not be generalizable and larger sized studies are warranted to confirm our findings. Also, because of the limited number of HALT cases, our study was probably underpowered to detect a less robust interaction between HALT and all-cause mortality. CTA was performed at 6 months and we have no information about the HALT status before that. However, based on the currently available data no optimal time schedule for repeated HALT screening that ensures that no cases are missed can be determined and frequently repeated CTA screening of asymptomatic patients would raise ethical issues. It cannot be excluded that certain associations between HALT and imaging findings, neurocognitive changes, or clinical events could not be recognized, due to the relatively small absolute number of patients diagnosed with HALT (the prevalence of HALT in our cohort was similar to that published in previous reports,31), which diminishes the statistical power of our calculations. Nonetheless, this limitation does not affect the validity of the found associations.

A 1.5 T MRI system was used. A 3 T system could have provided better accuracy; however, we used DTI instead of simple DWI, which (via 32 encoding gradient directions instead of only three in DWI) has higher sensitivity in lesion detection and better spatial resolution than plain DWI. In cases where follow-up cognitive assessment could not be performed, the most frequent reason for this was patient refusal, which might have introduced an important selection bias; however this is an inherent limitation of any serial cognitive test that requires patient cooperation.

Conclusion

In the present study, patients with HALT had a higher rate of new WMH and the presence of HALT was significantly associated with new WMH volumes. Increased WMH burden did not translate into impaired cognitive functioning during a 6-month follow-up.

Supplementary material

Supplementary materials are available at European Heart Journal—Cardiovascular Imaging online.

Acknowledgements

László Szakács for the statistical analysis.

Funding

National Heart Program, (NVKP_16-1–2016-0017); Thematic Excellence Programme (2020-4.1.1.-TKP2020). AIN—János Bolyai scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Author notes

Astrid Apor and Andrea Bartykowszki contributed equally to this work.

Conflict of interest: P.M.-H. is shareholder of Neumann Medical Ltd.; B.M. received institutional grants from Boston Scientific and Medtronic, speakers fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Astra Zeneca, Biotronic, Abbott, Novartis, and is advisory board member at Boehringer Ingelheim, Astra Zeneca, and Novartis.