-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Katharine A Manning, Jason Bowman, Shunichi Nakagawa, Kei Ouchi, Common mistakes and evidence-based approaches in goals-of-care conversations for seriously ill older adults in cardiac care unit, European Heart Journal. Acute Cardiovascular Care, Volume 13, Issue 8, August 2024, Pages 629–633, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjacc/zuae045

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

For older adults with serious, life-limiting illnesses near the end of life, clinicians frequently face difficult decisions about the medical care they provide because of clinical uncertainty. This difficulty is further complicated by unique challenges and medical advancements for patients with advanced heart diseases. In this article, we describe common mistakes encountered by clinicians when having goals-of-care conversations (e.g. conversations between clinicians and seriously ill patients/surrogates to discuss patient’s values and goals for clinical care near the end of life.). Then, we delineate an evidence-based approach in goals-of-care conversations and highlight the unique challenges around decision-making in the cardiac intensive care unit.

Introduction

For older adults with serious, life-limiting illnesses near the end of life, clinicians frequently face difficult decisions about the medical care they provide because of clinical uncertainty. This difficulty is further complicated by unique challenges and medical advancements for patients with advanced heart diseases.

The historic, paternalistic approach of clinicians making medical decisions with little or no input from patients and their families has rightfully been condemned. However, in many institutions, it has been replaced by a model in which clinicians offer a list of options and then defer to the patient and family to make a choice with little to no guidance (i.e. informed consent approach). For older adults with serious illnesses possibly near the end of life, this approach is ethically problematic and puts an incredible decision-making burden on the patients and their surrogates. Neither of these extreme approaches best leads to true patient-centred care, and finding the right middle ground for an individual patient can be challenging. Prior literature has shown that attempted shared decision-making conversations for seriously ill patients often lack important elements, and clinicians often do not even realize this.1,2

In this article, we will highlight common mistakes that we have made in our careers when having goals-of-care conversations (e.g. conversations between clinicians and seriously ill patients/surrogates to discuss patient’s values and goals for clinical care near the end of life.). By doing so, we will describe an evidence-based approach or ‘procedure’ that clinicians can use when having goals-of-care conversations and will also describe best practices and pitfalls when using this approach for older adults with advanced heart diseases. Finally, we will also discuss some of the unique challenges around decision-making conversations for critically ill patients in the cardiac intensive care unit (‘CCU’). Like any other procedure, learning to lead shared decision-making better for these complex and vulnerable patients takes time, practice, and collaboration.

Mistakes we have made and why

When older adults with advanced heart diseases are in the CCU, clinicians must determine the code status promptly to ensure patient-centred care. In such cases, the probability that these patients are successfully discharged from the hospital may be low, especially with good post-ICU quality of life. Here are the common mistakes that we personally made when making this decision. By highlighting these mistakes, we will explain why they are common misconceptions.

Mistake 1: explaining the medical conditions in detail with jargon

All clinicians are trained to provide as much information as possible to help patients/surrogates understand the severity of the current conditions. By helping patients/surrogates understand the illness at hand, we hope to ensure they are well informed about the decision-making regarding medical interventions. However, clinicians tend to over-explain the conditions in detail with jargon (e.g. ‘Your father’s heart condition is critical where the pump function is so bad that requires life-support.’), which fails to address the main message required for decision-making (e.g. ‘The condition is life-threatening no matter what we do.’).

Mistake 2: failing to respond to expected emotions

If the main message regarding the seriousness of the condition is successfully communicated, all patients and their surrogates are expected to experience a surge in emotional distress. This might be demonstrated by anger, sadness, surprise, or doubt towards clinical teams. The cognitive-emotional decision-making conceptual framework explains that in such moments of psychological stress, humans are unable to participate in cognitive decision-making.3 Therefore, responding to expected negative emotions is paramount to fostering patient/surrogate understanding and building therapeutic alliances. Established serious illness communication skills exist to respond to such emotion,4 which needs to be used amply.

Mistake 3: not seeking to know the patient as a person

Older adults with serious illnesses have expressed that conditions exist that they would consider worse than dying,5 and 87% even state that they would give up 1 year of life to avoid dying in the ICU.6 Therefore, seeking to understand patients’ baseline function and perceived quality of life prior to acute health decompensation is required to individualize the care to their goals. By seeking to understand patients’ values and goals, clinicians can deepen that therapeutic alliance with the patients/surrogates. Ultimately, clinicians must aim to make clinical recommendations about the medical intervention based on the patient’s anticipated quality of life rather than survival probabilities.7 Therefore, understanding patient’s values and goals is inevitable in making patient-centred recommendations.

Mistake 4: being a logic bully

After explaining the medical situation, anticipated outcomes, and risks/benefits/alternatives of possible medical interventions, clinicians are sometimes left thinking, ‘Why does this patient/surrogate not understand that choosing to undergo this procedure is a bad idea?’ When this happens, clinicians are inclined to provide more information to help patients/surrogates ‘better understand’ what they have not grasped. Since clinicians have so much more knowledge and experience in medical conditions, we can often ‘win’ the logistical argument with the patients/surrogates by providing more legitimate clinical facts. However, this approach (i.e. ‘logic bully’8) reduces the trust that patients/surrogates and discredits clinicians’ expertise by forcing patients/surrogates to make decisions that they are not psychologically ready to make (e.g. ventilator withdrawal near the end of life). The primary purpose of the shared decision-making is not to ‘win’ the argument; rather, by seeking to understand patients’/surrogates’ perspectives, clinicians must strive to reach a mutually agreeable treatment option aligned with the patient’s values and goals.

Mistake 5: asking patients/surrogates to make a choice

‘Would your (patient) want to be placed on a breathing machine?’ is a common question still being asked by many junior clinicians when patients are being admitted to hospitals. When patients/surrogates are asked to choose whether they want to partake in a medical intervention, they are in a disadvantaged position because they would never understand the consequences of this decision-making as much as clinician experts do. Furthermore, the psychological burden of potentially making an end-of-life care decision that they may later regret is solely weighed on their shoulders. Especially when the decision-making is possibly about end-of-life care, clinicians must bear the burden of this decision-making by making clinical recommendations about what care might be best for the patient after understanding the patient’s values and goals.

A structured approach to shared decision-making

To overcome the common mistakes/challenges above to ensure that the code status decision-making is conducted in a consistent manner for every patient with advanced heart disease, we propose the following structured approach (Table 1)9:

| Steps . | Examples . |

|---|---|

| 1. Establish crisis | I wish we met under different circumstances. Your loved one is very sick, and we have to make a decision about what care is right for (him/her). |

| 2. Assess what is known | What have you heard about what happened today? |

| 3. Break bad news | Warning shot: I have serious news. Would it be ok if I share this? Headline: Your loved one is not breathing well, and I’m worried that he may die. |

| 4. Align | We will work together to decide on the best possible care for him. |

| 5. Assess baseline function and values | How much was he able to do when he was well before today? What were the abilities critical to live? Minimal quality of life acceptable? States worse than dying? How much more? |

| 6. Summarize | What I heard is ___. He considered ___ important. Did I get that right? |

| 7. Recommend | I would recommend intensive treatment focused on ___. I will do ___, and I will not do ___. |

| Steps . | Examples . |

|---|---|

| 1. Establish crisis | I wish we met under different circumstances. Your loved one is very sick, and we have to make a decision about what care is right for (him/her). |

| 2. Assess what is known | What have you heard about what happened today? |

| 3. Break bad news | Warning shot: I have serious news. Would it be ok if I share this? Headline: Your loved one is not breathing well, and I’m worried that he may die. |

| 4. Align | We will work together to decide on the best possible care for him. |

| 5. Assess baseline function and values | How much was he able to do when he was well before today? What were the abilities critical to live? Minimal quality of life acceptable? States worse than dying? How much more? |

| 6. Summarize | What I heard is ___. He considered ___ important. Did I get that right? |

| 7. Recommend | I would recommend intensive treatment focused on ___. I will do ___, and I will not do ___. |

| Steps . | Examples . |

|---|---|

| 1. Establish crisis | I wish we met under different circumstances. Your loved one is very sick, and we have to make a decision about what care is right for (him/her). |

| 2. Assess what is known | What have you heard about what happened today? |

| 3. Break bad news | Warning shot: I have serious news. Would it be ok if I share this? Headline: Your loved one is not breathing well, and I’m worried that he may die. |

| 4. Align | We will work together to decide on the best possible care for him. |

| 5. Assess baseline function and values | How much was he able to do when he was well before today? What were the abilities critical to live? Minimal quality of life acceptable? States worse than dying? How much more? |

| 6. Summarize | What I heard is ___. He considered ___ important. Did I get that right? |

| 7. Recommend | I would recommend intensive treatment focused on ___. I will do ___, and I will not do ___. |

| Steps . | Examples . |

|---|---|

| 1. Establish crisis | I wish we met under different circumstances. Your loved one is very sick, and we have to make a decision about what care is right for (him/her). |

| 2. Assess what is known | What have you heard about what happened today? |

| 3. Break bad news | Warning shot: I have serious news. Would it be ok if I share this? Headline: Your loved one is not breathing well, and I’m worried that he may die. |

| 4. Align | We will work together to decide on the best possible care for him. |

| 5. Assess baseline function and values | How much was he able to do when he was well before today? What were the abilities critical to live? Minimal quality of life acceptable? States worse than dying? How much more? |

| 6. Summarize | What I heard is ___. He considered ___ important. Did I get that right? |

| 7. Recommend | I would recommend intensive treatment focused on ___. I will do ___, and I will not do ___. |

Ensuring these steps to be followed will allow clinicians to solicit the correct types of information to lead to patient-centred recommendations about potentially end-of-life care. Videos demonstrating the above skills can be found on this link.

Specific challenges in CCU

With advances in cardiovascular care, new specific challenges arose to ensure patient-centred care in the CCU settings. We will highlight specific examples and potential mitigation plans here.

Increase in the use of temporary mechanical circulatory support

The utilization of temporary mechanical circulatory support (tMCS), particularly percutaneous ventricular assist devices (VADs) and veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), has witnessed a substantial rise within the CCU over the past decade.10 It is well known that the clinical trajectory of heart failure is unpredictable. Patients with advanced heart failure experience multiple episodes of exacerbation. At the nadir of exacerbation, they are very sick, but with proper treatment, their condition could improve to the prior level. This could give patients, families, and sometimes even physicians a false impression that this recovery could be achievable repeatedly. In cardiogenic shock, while mortality remains as high as over 50%,11,12 some patients could be salvaged by tMCS, which makes it even harder to prognosticate, and as a result, goals-of-care conversations become extremely challenging.

Implementation of early and regular goals-of-care meetings

Particularly for patients experiencing cardiogenic shock necessitating tMCS, the endorsement of early and regular goals-of-care meetings, conducted weekly or biweekly, has been advocated.13 The constant influx of day-to-day medical updates often overwhelms patients and their families, making it challenging to maintain a comprehensive understanding of the larger clinical picture.

Within these meetings, a pivotal aspect is the communication of adverse prognostic information (as outlined in Step 3 Breaking bad news in Table 1 above). Given the inherent prognostic uncertainty associated with cardiogenic shock, especially with tMCS, clinicians should approach the delicate task of conveying information judiciously about the patient’s condition and expected prognosis. Mechanically delivering prognostic details has been demonstrated to exacerbate post-traumatic stress disorder without yielding any discernible benefits for families.14 It would be advised only to give some warning shots (i.e. verbal warning that hints at bad prognosis) and to make it relatively vague in the beginning (e.g. ‘He is very sick, and we are worried about how soon or well he can recover’ rather than ‘We do not think he will survive’). Balancing optimism and clinical uncertainty as above would help in developing a rapport and therapeutic alliance with patients and families that the clinical team is working to deliver the best care possible for the patient. The longer duration of ECMO support has been shown as a predictor of in-hospital mortality.15,16 As such, the emphasis on the prognostic disclosure should be gradually strengthened as time goes on. In addition, clinicians should continue to explore patient’s values and goals in the context of current critical illness, which may or may not be reversible.

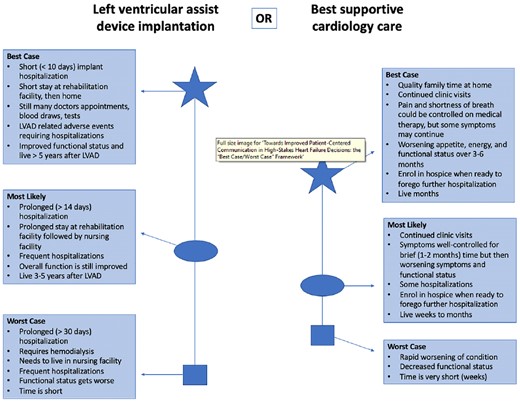

Use of the ‘best-case/worst-case’ framework in making a decision

Patients with cardiogenic shock who are on tMCS often face difficult decision-making, most importantly for advanced therapy, such as VAD or heart transplant. While various decision aids are proposed to facilitate this discussion,17 patients and families are usually overwhelmed with the situation in the CCU and tend to understand it as a false dichotomy of ‘life or death’. As a result, patients sometimes choose advanced therapy without fully understanding the implication of their choice (i.e. anticipated quality of life and physical function if the patient survives) nor the gravity of the situation.

The best-case/worst-case framework, originally developed to facilitate communication about high-risk surgery in older adults,18 has now been applied to many other areas, including dialysis19 or chemotherapy.20 It has also been advocated for liver transplant21 or left VAD.22

Using a pen and a piece of paper, clinicians create a handwritten infographic aid by drawing two vertical lines representing treatment options. A star at the top represents the best-case scenario, a box at the bottom depicts the worst-case scenario, and an oval depicts the most likely scenario (Figure 1). The tool helps clinicians to provide scenarios for each option in a more individualized way, depending on the circumstances. This helps patients and families to visualize the likelihood of outcomes predicted by experienced clinicians as well as the anticipated quality of life should the patient survive, ultimately allowing better understanding of each treatment option and equitizing outcome expectations between the clinical team and the patient and families.

Best-case/worst-case graphic aid example, adapted from Chuzi S, Tong W, Nakagawa S. Towards improved patient-centered communication in high-stakes heart failure decisions: the “best case/worst case” framework. J Card Fail. 2023;29(11):1561-3. Epub 20230619. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2023.06.010. PubMed PMID: 37343815.

‘Bridge to nowhere’

In instances where tMCS fails to yield recovery or advanced therapy due to catastrophic complications (e.g. strokes) or significant debility, tMCS becomes a ‘bridge to nowhere’.23 This scenario poses a particularly challenging ethical dilemma, especially when the patient remains awake and communicative during tMCS. Typically, the determination that there is no viable exit strategy, indicating ineligibility for advanced therapy, is reached through interdisciplinary collaboration. Once confirmed, the medical team must promptly convene a goals-of-care meeting. While prognostic information may have been uncertain up to this point, in the context of the ‘bridge to nowhere’ scenario of tMCS, the terminal implications of the current condition must be clearly stated to the patient and families.

Especially for awake patients, it is imperative to convey that tMCSs (and other life supports) are sustaining their current condition but that this condition can only be maintained within the CCU, and the time remaining is typically limited to weeks to months even if continued. Clinicians must delicately navigate discussions to explore the patient’s values and priorities based on this new baseline, as outlined in Step 5 in Table 1 above. In instances where patients and families struggle to accept the situation, continuation of all life support is warranted, as ethically, tMCS (or any form of life support) cannot be unilaterally discontinued.

Conversely, certain patients or their families may express that living on tMCS in the CCU is not acceptable quality of life. In such instances, clinicians must engage in meticulous discussions surrounding the potential withdrawal of tMCS, rooted in the individual’s values and priorities. Awake patients may express a continued appreciation for moments spent with family, while those lacking decision-making capacity may have family members who are apprehensive about the prospect of ‘pulling the plug’. In these complex scenarios, it may be advisable to recommend maintaining the current tMCS (and other life supports) without escalation, while also discouraging the pursuit of further invasive procedures. If patients or their families convey a sense of unbearable suffering and a desire to forgo prolonging the dying process, withdrawal of tMCS becomes the most appropriate course of action. In any event, the decision regarding which course of action to pursue will hinge upon the individual’s goals and priorities. Given the emotionally charged and sensitive nature of these discussions, the involvement of palliative care specialists is indispensable.

Conclusion

Older adults with advanced heart diseases face unique challenges in care decision-making towards the end of life. New medical advancements are actively changing the challenges with more prognostic uncertainty. Evidence-based approaches exist to lead this shared decision-making for older adults with advanced heart diseases. By following these steps, clinicians can better align the values and goals of the patients to the advanced therapies that are available.

Funding

K.O. is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K76AG064434) and Cambia Health Foundation. J.B. has previously been supported by the National Institute on Aging (2P01AG027296-11).

Data availability

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this research.

References

Author notes

Katharine A. Manning and Jason Bowman are co-first authors.

Conflict of interest: K.O. has received advisory fees from Jolly Good, Inc (a virtual reality company). All other authors have nothing to report.

Comments