-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Antonio Fagundes, David D Berg, Erin A Bohula, Vivian M Baird-Zars, Christopher F Barnett, Anthony P Carnicelli, Sunit-Preet Chaudhry, Jianping Guo, Ellen C Keeley, Benjamin B Kenigsberg, Venu Menon, P Elliott Miller, L Kristin Newby, Sean van Diepen, David A Morrow, Jason N Katz, for the CCCTN Investigators, End-of-life care in the cardiac intensive care unit: a contemporary view from the Critical Care Cardiology Trials Network (CCCTN) Registry, European Heart Journal. Acute Cardiovascular Care, Volume 11, Issue 3, March 2022, Pages 190–197, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjacc/zuab121

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Increases in life expectancy, comorbidities, and survival with complex cardiovascular conditions have changed the clinical profile of the patients in cardiac intensive care units (CICUs). In this environment, palliative care (PC) services are increasingly important. However, scarce information is available about the delivery of PC in CICUs.

The Critical Care Cardiology Trials Network (CCCTN) Registry is a network of tertiary care CICUs in North America. Between 2017 and 2020, up to 26 centres contributed an annual 2-month snapshot of all consecutive medical CICU admissions. We captured code status at admission and the decision for comfort measures only (CMO) before all deaths in the CICU. Of 13 422 patients, 10% died in the CICU and 2.6% were discharged to palliative hospice. Of patients who died in the CICU, 68% were CMO at death. In the CMO group, only 13% were do not resuscitate/do not intubate at admission. The median time from CICU admission to CMO decision was 3.4 days (25th–75th percentiles: 1.2–7.7) and ≥7 days in 27%. Time from CMO decision to death was <24 h in 88%, with a median of 3.8 h (25th–75th 1.0–10.3). Before a CMO decision, 78% received mechanical ventilation and 26% mechanical circulatory support. A PC provider team participated in the care of 41% of patients who died.

In a contemporary CICU registry, comfort measures preceded death in two-thirds of cases, frequently without PC involvement. The high utilization of advanced intensive care unit therapies and lengthy times to a CMO decision highlight a potential opportunity for early engagement of PC teams in CICU.

Introduction

Historically, the primary mission of the cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) was to favourably modify the natural history of acute myocardial infarction.1,2 However, in current practice, other cardiac patient populations that require intensive care have expanded and now outnumber patients with acute myocardial infarction.3 Patients with sepsis, acute kidney injury, respiratory and liver failure, in addition to other non-cardiac primary conditions have significantly increased in their prevalence in the CICU.4,5 Consequently, the profile of admissions to CICUs has shifted towards a preponderance of cases with multiple chronic cardiac and non-cardiac diseases, frequently with acute decompensation.4 Despite the utilization of advanced CICU therapies, the mortality rate remains high in this population.6

Over time, triage to the intensive care unit (ICU) at the end of life has increased.7–9 As such, engaging palliative care (PC) services in general ICU practice is gaining increasing interest.10 Palliative care aims to reduce suffering, alleviate symptoms, and improve quality of life. The World Health Organization describes PC goals as the prevention, assessment, and multidisciplinary treatment of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual suffering.11 With changes in CICU composition, PC services appear to be increasingly relevant. However, few studies have assessed the epidemiology of CICU end-of-life practices. Therefore, we sought to describe the patterns of end-of-life decisions in a contemporary North American registry of CICU patients.

Methods

Study design and data sources

The Critical Care Cardiology Trials Network (CCCTN) is a collaborative network of advanced CICUs in the USA and Canada. The TIMI Study Group, Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA, USA) functions as the coordinating centre, with scientific oversight by academic executive and steering committees. The design and methods of the CCCTN Registry have been described in detail.6 Data are collected with a waiver of consent due to the minimal risk associated with registry enrolment (no personal identifying health information). The protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at Brigham and Women's Hospital and each of the participating centres. For collaboration using these data, please contact the corresponding author.

Patient population

Between September 2017 and September 2020, participating centres contributed an annual 2-month snapshot of all consecutive admissions to the CICU in up to 26 sites. Data were entered into a centralized, electronic case report form with remote monitoring of data quality by the TIMI Study Group.6 The following definitions were used: (i) comfort measures only (CMO): treatment of a person where the natural dying process is permitted to occur; the specific implementation varied by site but usually includes withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies; (ii) do not resuscitate/do not intubate (DNR/DNI) status indicates a patient that does not want to receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation or intubation in the event of cardiopulmonary arrest; (iii) full code: the decision that if a patient has a cardiac arrest, resuscitation procedures will be provided including chest compressions, intubation, and defibrillation. We captured whether a decision for CMO was made at any time during the CICU stay before all deaths. In the collection period from October 2019 through September 2020, data capture was expanded to include code status at admission and PC team consultations before death.

Statistical analyses

To describe CMO use patterns in the CICU, we identified all patients in CCCTN who died during the CICU course, then stratified by CMO status at CICU admission. To assess the evolution of code status during the CICU admission, we stratified the study population by initial code status and code status before death. The times from CICU admission to implementation of CMO, CMO decision to death, and intubation to CMO decision were calculated. Results are reported as counts and percentages for categorical variables, and for continuous variables as medians with 25th and 75th percentiles. Comparisons were made using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. Special groups of interest in the analysis included patients with cardiac arrest as a CICU indication and those who were managed with mechanical circulatory support (MCS). Statistical significance was assessed at a nominal α level of 0.05. All reported P-values were two-sided. All statistical computations were performed with SAS System V9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

A total of 13 422 admissions were recorded in the CCCTN registry, of which 5191 were from the 2019–20 annual collection cycle with data on PC consultation. Of the total cohort, 10% died and 2.6% were discharged to palliative hospice. Before death in the CICU, 68% (N = 562) had their care transitioned to CMO (Supplementary material online, Figure S1). Baseline characteristics, according to CMO status before death, are summarized in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by comfort measures only practice among patients who died in the cardiac intensive care unit

| Characteristic . | CMO . | No CMO . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 562) . | (N = 267) . | ||

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | 70.0 (59.0–78.0) | 67.0 (56.0–77.0) | 0.03 |

| Female | 226 (40.2) | 114 (42.7) | 0.50 |

| Caucasian | 395 (70.3) | 158 (59.2) | 0.07 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 23 (4.1) | 23 (8.6) | 0.02 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.4 (23.7–32.5) | 28.7 (23.7–33.7) | 0.15 |

| SOFA score | 11 (8–13) | 10 (7–14) | 0.05 |

| CV history | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 220 (39.1) | 114 (42.7) | 0.33 |

| Hypertension | 360 (64.1) | 171 (64.0) | 0.10 |

| Coronary artery disease | 227 (40.4) | 102 (38.2) | 0.54 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 88 (15.7) | 29 (10.9) | 0.06 |

| Heart failure | 262 (46.6) | 117 (43.8) | 0.45 |

| Heart transplant | 10 (1.8) | 7 (2.6) | 0.42 |

| Severe valvular disease | 47 (8.4) | 28 (10.5) | 0.32 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 9 (1.6) | 5 (1.9) | 0.78 |

| Congenital heart disease | 55 (9.8) | 29 (10.9) | 0.63 |

| Heart failure | 262 (46.6) | 117 (43.8) | 0.45 |

| LV ejection fraction <30% | 120 (21.3) | 58 (21.7) | 0.93 |

| Chronic general medical conditions | |||

| Chronic kidney disease receiving dialysis | 55(9.8) | 25 (9.4) | 0.90 |

| Significant pulmonary disease | 122 (21.7) | 60 (22.5) | 0.80 |

| Significant liver disease | 36 (6.4) | 10 (3.7) | 0.12 |

| Significant dementia | 18 (3.2) | 3 (1.1) | 0.10 |

| Active cancer | 61 (10.9) | 25 (9.4) | 0.51 |

| Characteristic . | CMO . | No CMO . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 562) . | (N = 267) . | ||

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | 70.0 (59.0–78.0) | 67.0 (56.0–77.0) | 0.03 |

| Female | 226 (40.2) | 114 (42.7) | 0.50 |

| Caucasian | 395 (70.3) | 158 (59.2) | 0.07 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 23 (4.1) | 23 (8.6) | 0.02 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.4 (23.7–32.5) | 28.7 (23.7–33.7) | 0.15 |

| SOFA score | 11 (8–13) | 10 (7–14) | 0.05 |

| CV history | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 220 (39.1) | 114 (42.7) | 0.33 |

| Hypertension | 360 (64.1) | 171 (64.0) | 0.10 |

| Coronary artery disease | 227 (40.4) | 102 (38.2) | 0.54 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 88 (15.7) | 29 (10.9) | 0.06 |

| Heart failure | 262 (46.6) | 117 (43.8) | 0.45 |

| Heart transplant | 10 (1.8) | 7 (2.6) | 0.42 |

| Severe valvular disease | 47 (8.4) | 28 (10.5) | 0.32 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 9 (1.6) | 5 (1.9) | 0.78 |

| Congenital heart disease | 55 (9.8) | 29 (10.9) | 0.63 |

| Heart failure | 262 (46.6) | 117 (43.8) | 0.45 |

| LV ejection fraction <30% | 120 (21.3) | 58 (21.7) | 0.93 |

| Chronic general medical conditions | |||

| Chronic kidney disease receiving dialysis | 55(9.8) | 25 (9.4) | 0.90 |

| Significant pulmonary disease | 122 (21.7) | 60 (22.5) | 0.80 |

| Significant liver disease | 36 (6.4) | 10 (3.7) | 0.12 |

| Significant dementia | 18 (3.2) | 3 (1.1) | 0.10 |

| Active cancer | 61 (10.9) | 25 (9.4) | 0.51 |

Values are median (interquartile range) or n (%).

BMI, body mass index; CMO, comfort measures only; CV, cardiovascular; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; LV, left ventricle; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; VAD, ventricular assist device.

Baseline characteristics by comfort measures only practice among patients who died in the cardiac intensive care unit

| Characteristic . | CMO . | No CMO . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 562) . | (N = 267) . | ||

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | 70.0 (59.0–78.0) | 67.0 (56.0–77.0) | 0.03 |

| Female | 226 (40.2) | 114 (42.7) | 0.50 |

| Caucasian | 395 (70.3) | 158 (59.2) | 0.07 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 23 (4.1) | 23 (8.6) | 0.02 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.4 (23.7–32.5) | 28.7 (23.7–33.7) | 0.15 |

| SOFA score | 11 (8–13) | 10 (7–14) | 0.05 |

| CV history | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 220 (39.1) | 114 (42.7) | 0.33 |

| Hypertension | 360 (64.1) | 171 (64.0) | 0.10 |

| Coronary artery disease | 227 (40.4) | 102 (38.2) | 0.54 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 88 (15.7) | 29 (10.9) | 0.06 |

| Heart failure | 262 (46.6) | 117 (43.8) | 0.45 |

| Heart transplant | 10 (1.8) | 7 (2.6) | 0.42 |

| Severe valvular disease | 47 (8.4) | 28 (10.5) | 0.32 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 9 (1.6) | 5 (1.9) | 0.78 |

| Congenital heart disease | 55 (9.8) | 29 (10.9) | 0.63 |

| Heart failure | 262 (46.6) | 117 (43.8) | 0.45 |

| LV ejection fraction <30% | 120 (21.3) | 58 (21.7) | 0.93 |

| Chronic general medical conditions | |||

| Chronic kidney disease receiving dialysis | 55(9.8) | 25 (9.4) | 0.90 |

| Significant pulmonary disease | 122 (21.7) | 60 (22.5) | 0.80 |

| Significant liver disease | 36 (6.4) | 10 (3.7) | 0.12 |

| Significant dementia | 18 (3.2) | 3 (1.1) | 0.10 |

| Active cancer | 61 (10.9) | 25 (9.4) | 0.51 |

| Characteristic . | CMO . | No CMO . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 562) . | (N = 267) . | ||

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | 70.0 (59.0–78.0) | 67.0 (56.0–77.0) | 0.03 |

| Female | 226 (40.2) | 114 (42.7) | 0.50 |

| Caucasian | 395 (70.3) | 158 (59.2) | 0.07 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 23 (4.1) | 23 (8.6) | 0.02 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.4 (23.7–32.5) | 28.7 (23.7–33.7) | 0.15 |

| SOFA score | 11 (8–13) | 10 (7–14) | 0.05 |

| CV history | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 220 (39.1) | 114 (42.7) | 0.33 |

| Hypertension | 360 (64.1) | 171 (64.0) | 0.10 |

| Coronary artery disease | 227 (40.4) | 102 (38.2) | 0.54 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 88 (15.7) | 29 (10.9) | 0.06 |

| Heart failure | 262 (46.6) | 117 (43.8) | 0.45 |

| Heart transplant | 10 (1.8) | 7 (2.6) | 0.42 |

| Severe valvular disease | 47 (8.4) | 28 (10.5) | 0.32 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 9 (1.6) | 5 (1.9) | 0.78 |

| Congenital heart disease | 55 (9.8) | 29 (10.9) | 0.63 |

| Heart failure | 262 (46.6) | 117 (43.8) | 0.45 |

| LV ejection fraction <30% | 120 (21.3) | 58 (21.7) | 0.93 |

| Chronic general medical conditions | |||

| Chronic kidney disease receiving dialysis | 55(9.8) | 25 (9.4) | 0.90 |

| Significant pulmonary disease | 122 (21.7) | 60 (22.5) | 0.80 |

| Significant liver disease | 36 (6.4) | 10 (3.7) | 0.12 |

| Significant dementia | 18 (3.2) | 3 (1.1) | 0.10 |

| Active cancer | 61 (10.9) | 25 (9.4) | 0.51 |

Values are median (interquartile range) or n (%).

BMI, body mass index; CMO, comfort measures only; CV, cardiovascular; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; LV, left ventricle; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; VAD, ventricular assist device.

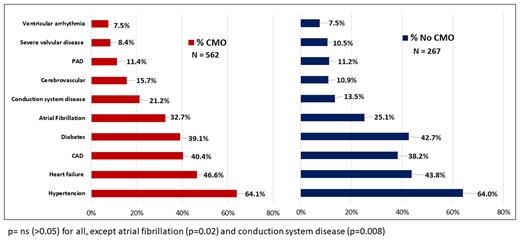

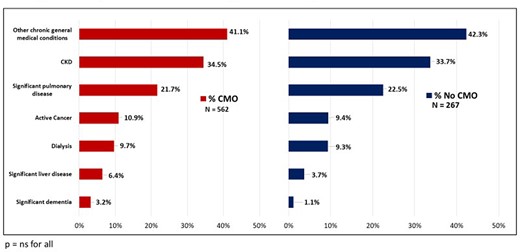

Compared with patients who died in the CICU without CMO care, CMO patients were older (70 vs. 67 years, P = 0.03) and less frequently Hispanic or Latino (4.1% vs. 8.6%, P = 0.02; Table 1; Supplementary material online, Figures S2 and S3). There were no statistically significant differences between the burden of pre-existing cardiovascular disease and chronic general medical conditions, including active cancer and dementia (Figures 1 and 2). Comfort measures only patients were more frequently admitted with a general medical problem and a history of cardiovascular disease (11.2% vs. 6.7%, P = 0.02) rather than a primary acute cardiac problem. The most common primary diagnoses at CICU admission among patients who ultimately transitioned to CMO care were cardiac arrest (19.4%), acute coronary syndrome (15.5%), heart failure (13.9%), and cardiogenic shock (13%). Indications for ICU-level care of respiratory insufficiency and mixed or distributive shock states were associated with CMO status (Table 2). The proportion of cardiac arrest patients who transitioned to CMO (66%) was consistent with the overall cohort (Supplementary material online, Table S1). Patients who had CMO care had slightly greater disease severity at baseline by the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (11 vs. 10, P = 0.05; Supplementary material online, Figure S4). Comfort measures only patients also had a longer length of stay (median 3.8 vs. 2.0 days, P < 0.0001; Supplementary material online, Figure S5).

Cardiovascular history of comfort measures only and no comfort measures only groups.

Chronic general medical conditions among comfort measures only and no comfort measures only patients.

| CICU indication . | Deceased patients . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 829 . | |||

| CMO . | No CMO . | ||

| N = 562 . | N = 267 . | ||

| n (%) . | n (%) . | ||

| Respiratory insufficiency | 410 (73.0) | 171 (64.0) | <0.01 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 257 (45.7) | 151 (56.6) | <0.01 |

| Distributive or mixed shock | 183 (32.6) | 54 (20.2) | <0.01 |

| Hypotension without shock | 26 (4.6) | 21 (7.9) | 0.06 |

| Cardiac arrest | 214 (38.1) | 109 (40.8) | 0.45 |

| Unstable arrhythmia | 116 (20.6) | 61 (22.8) | 0.05 |

| Need for RRT | 78 (13.9) | 53 (19.9) | 0.03 |

| CICU indication . | Deceased patients . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 829 . | |||

| CMO . | No CMO . | ||

| N = 562 . | N = 267 . | ||

| n (%) . | n (%) . | ||

| Respiratory insufficiency | 410 (73.0) | 171 (64.0) | <0.01 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 257 (45.7) | 151 (56.6) | <0.01 |

| Distributive or mixed shock | 183 (32.6) | 54 (20.2) | <0.01 |

| Hypotension without shock | 26 (4.6) | 21 (7.9) | 0.06 |

| Cardiac arrest | 214 (38.1) | 109 (40.8) | 0.45 |

| Unstable arrhythmia | 116 (20.6) | 61 (22.8) | 0.05 |

| Need for RRT | 78 (13.9) | 53 (19.9) | 0.03 |

CMO, comfort measures only; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

| CICU indication . | Deceased patients . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 829 . | |||

| CMO . | No CMO . | ||

| N = 562 . | N = 267 . | ||

| n (%) . | n (%) . | ||

| Respiratory insufficiency | 410 (73.0) | 171 (64.0) | <0.01 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 257 (45.7) | 151 (56.6) | <0.01 |

| Distributive or mixed shock | 183 (32.6) | 54 (20.2) | <0.01 |

| Hypotension without shock | 26 (4.6) | 21 (7.9) | 0.06 |

| Cardiac arrest | 214 (38.1) | 109 (40.8) | 0.45 |

| Unstable arrhythmia | 116 (20.6) | 61 (22.8) | 0.05 |

| Need for RRT | 78 (13.9) | 53 (19.9) | 0.03 |

| CICU indication . | Deceased patients . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 829 . | |||

| CMO . | No CMO . | ||

| N = 562 . | N = 267 . | ||

| n (%) . | n (%) . | ||

| Respiratory insufficiency | 410 (73.0) | 171 (64.0) | <0.01 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 257 (45.7) | 151 (56.6) | <0.01 |

| Distributive or mixed shock | 183 (32.6) | 54 (20.2) | <0.01 |

| Hypotension without shock | 26 (4.6) | 21 (7.9) | 0.06 |

| Cardiac arrest | 214 (38.1) | 109 (40.8) | 0.45 |

| Unstable arrhythmia | 116 (20.6) | 61 (22.8) | 0.05 |

| Need for RRT | 78 (13.9) | 53 (19.9) | 0.03 |

CMO, comfort measures only; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

Use of advanced cardiac intensive care unit therapies

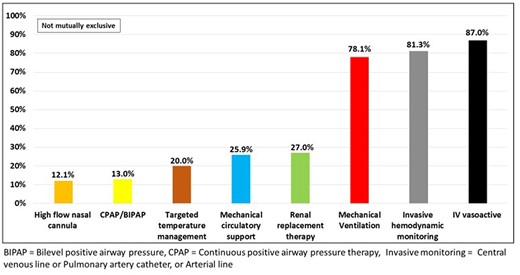

Patients who ultimately transitioned to CMO had substantial preceding use of advanced CICU therapies with 87% receiving vasoactive drugs, 81% invasive haemodynamic monitoring, 78% mechanical ventilation, 27% renal replacement therapy, and 26% MCS (Figure 3). Of deaths among patients managed with MCS, 64% of them ultimately transitioned to CMO.

Use of advanced cardiac intensive care unit therapies among comfort measures only patients.

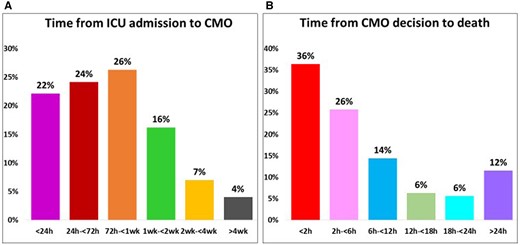

The median time from CICU admission to CMO decision was 3.4 days (25th–75th: 1.2–7.7 days), with the majority of CMO decisions (53.7%) occurring >72 h from admission (Figure 4). The median time from a CMO decision to death was only 3.8 h (25th–75th: 0.96–10.3 h) and was <24 h in 88% of the cases. The median time from MCS initiation to transition to CMO was 1.9 days, while the CMO decision to death was 1.9 h. Of the total deaths, 34% of the intubated patients were extubated palliatively. The median time from intubation to CMO decision was 5.0 days (25th–75th: 2.2–11.6 days). Patients >70 years old had shorter times from admission to CMO decision and from transition to CMO care to death (Supplementary material online, Figure S6).

(A) Time from intensive care unit admission to comfort measures only and (B) time from comfort measures only decision to death.

There was wide variability across CCCTN sites regarding CMO use, ranging from 40% to 94%, before death (Supplementary material online, Figure S7).

Evolution of code status and palliative care consultation in cardiac intensive care unit

Of the 3412 admissions with expanded data capture, at presentation, 95% were classified as full code and the remainder as DNR or DNI. Of the initially DNR or DNI group, 50% received vasoactive drugs and 17% mechanical ventilation (Supplementary material online, Figure S8). Of the patients who eventually died, 89% were full code at admission. Patients admitted with a DNR or DNI status were older and more frequently female and had more pre-existing cardiovascular disease (Supplementary material online, Table S2). Of the patients who transitioned to CMO care before death, 87% were classified at admission as full code. Consultation to PC teams prior to death was made in 41% of the cases, with no significant difference based on code status at admission. In the same direction of CMO, there was a wide variability of PC consultation before death among sites, ranging from 7% to 100% (Supplementary material online, Figure S9). Among patients that had a PC consultation before death, CMO care was initiated in 78% of the cases. However, among patients without PC consultation, CMO care was used in 50.6%.

Discussion

In a contemporary registry of CICU care, comfort measures were widely used (two-thirds of deaths) but formal PC consultation was obtained in less than a half of patients who died in the CICU. Moreover, we identified a median period of 3.4 days to CMO decision, with substantial use of advanced CICU therapies preceding CMO, and only hours from a CMO decision to death.

Deployment of comfort measures and palliative care consultation in the cardiac intensive care unit

In this large North American registry of consecutive admissions to the CICU, we observed that comfort measures preceded death in a majority of cases. This finding indicates that CICU practitioners frequently implement some PC measures. Although CMO patients were older, perhaps surprisingly, comorbid conditions were not substantially different compared with those who died without transition to comfort measures. For example, conditions often managed with use of PC strategies, such as advanced lung and liver disease, dementia, and cancer, were not significantly more frequent in the CMO group. We also observed possible differences based on ethnicity that may stem from cultural or religious differences or language barriers; a finding that is consistent with previous studies.12

Our results also highlight the high use of advanced therapies before death in patients who were transitioned to CMO care, with 78% of such patients receiving mechanical ventilation and 26% MCS. The short time interval between CMO decision and death probably reflects the dependence on and subsequent withdrawal of vital organ support. Moreover, the median time from ICU admission to CMO was 3.4 days and was >72 h in 53% of cases. Such time may be necessary for patients to receive initial treatment for an acute condition, and reassessment if the patient develops multiple organ failure despite initial therapies. However, the finding also raises the possibility that, for some patients, an end-of-life care approach could have been initiated earlier. The time between admission and the CMO decision may also reflect the challenges in establishing a PC path. The low involvement of PC teams in the process identifies a potential opportunity for specialized assistance in the care of these CICU patients. Our data show that CMO was used more frequently in patients who received PC consultation before death. Moreover, the wide variability in use of CMO and PC consultation among sites identifies substantial practice variation. It is important to understand the drivers of such variability that may benefit from structured or more standardized strategies.

Need for palliative care practices in the cardiac intensive care unit

Patients in the final stages of chronic illnesses are often admitted to an ICU.9 In the USA, 22% of the total population dies in an ICU, often after a long period of hospitalization and deployment of advanced ICU therapies and life support.13 Some studies point to a benefit in the early involvement of specialized multidisciplinary PC teams with dedicated time to approach patients, families, and CICU members.14,15 Early integrated PC intervention can mitigate suffering and improve patient-focused care, and enhance communication between patients, relatives, and the multidisciplinary teams.16 Ensuring awareness of and access to PC has been demonstrated to create a culture that enhances professional education, training, and early PC group involvement.17 A goal of such education is to promote the understanding that CICU treatments and PC can be complementary.18–20

End-of-life care has been applied in cardiology in patients with advanced heart failure, and MCS. Ideally, heart failure specialists’ care should be aligned with PC specialists. Patients with advanced heart failure often spend long periods in the hospital and often PC teams are engaged in the care of these patients in the CICU, to align goals of care and end-of-life decisions.21–23 In addition to providing care that meets their physical and emotional needs at the end of life, PC may reduce the performance of invasive, and oftentimes costly, interventions in the final days of life that do not provide meaningful benefit to the patient and can thus improve the quality of care while achieving cost savings.24–26

Our finding of high use of comfort measures in the CICU is in line with the CICU population’s evolving epidemiological profile composed mainly of elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. Consistent with our data, Naib et al.27 reported end-of-life discussions in 72% of cases (n = 85), with the primary CICU team leading the approach in more than 50% of them. Frequently, CICU patients lack the decision-making capacity and advanced directives are not available.28 Therefore, complex discussions are necessary with families regarding prognosis, limiting suffering, end-of-life support, and withholding or withdrawing interventions.7 A key implication of our report is that a patient’s medical status may mitigate the wisdom of attempting to resuscitate and pursue invasive therapies. Accepted definitions of beneficence warrant that providers consider both the long term and the immediate value and benefit to patients and families, weighing concepts of futility, and the overall good. The discussion about death and the end-of-life period is often surrounded by misconceptions and discomfort among clinicians, patients, and families. Cultural and religious beliefs of the patient and family can also have important implications for how healthcare technology should be used at the end of life.29 As an addition to this complexity, the urgency of procedures and decisions contribute another stressor aspect to these discussions in the CICU. As well, it may be unclear in these situations who is responsible for final decision-making regarding specific interventions or therapies.

As such, these conversations benefit from specific training and continuing medical education focused on good communication and knowledge of ethical principles.30 These particular skills have been introduced into the formal practice of general intensive care physicians.31 There is a growing interest in training in PC among CICU teams; although this local skill-building in CICUs does not replace the role of the PC specialist.17 However, our study revealed substantial variability in PC consultation between centres. The reasons for the lack of engagement of PC teams in some sites could be related to specific regional practices, lack of resources and specialists, different reimbursement systems, or the practice of implementing PC by the CICU team themselves.

Limitations

First, our study population was drawn from a network of tertiary care CICUs in the USA and Canada based at academic medical centres and may not be generalizable to other CICU settings. Second, our findings are specific to the context of triage to a CICU and do not necessarily reflect PC services’ epidemiology in patients managed outside the CICU. Third, the use of PC consultation was recorded only in the 2019–20 annual collection period. Lastly, our database does not capture granular details regarding PC delivery, such as symptom control strategies or specific triggers and timing of PC conversations. Future directions should deepen knowledge about end-of-life decisions in the CICU, better addressing the context of patients after cardiac arrest, advanced heart failure, and ventricular assist devices, in addition to barriers related to language, culture, and religion.

Conclusions

In the CCCTN registry, the use of comfort measures preceded death in the CICU in a majority of cases. However, before the CMO decision, there was substantial use of advanced CICU therapies and limited engagement of PC teams. Palliative care research in the CICU is likely to be important for defining goals and assessing methods for end-of-life care in critical care cardiology.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal: Acute Cardiovascular Care online.

Conflict of interest: A.F. Jr. is supported by a post-doctoral research grant from the Lemann Foundation. A.P.C. is supported by a T32 grant funding from the National Institute of Health NIH. D.D.B., E.A.B., V.M.B.-Z., C.F.B., S.-P.C., J.G., E.C.K., B.B.K., V.M., P.E.M., L.K.N., S.v.D., D.A.M., and J.N.K. have declared no conflicts related to this work.

References

Author notes

David A. Morrow and Jason N. Katz contributed equally to this study.

Comments