-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Devin Kreitman, Melody A Keena, Anne L Nielsen, George Hamilton, Effects of Temperature on Development and Survival of Nymphal Lycorma delicatula (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae), Environmental Entomology, Volume 50, Issue 1, February 2021, Pages 183–191, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvaa155

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Lycorma delicatula (White), an invasive planthopper originally from Asia, is an emerging pest in North America. It is important to understand its phenology in order to determine its potential range in the United States. Lycorma delicatula nymphs were reared on Ailanthus altissima (Miller) (Sapindales: Simaroubaceae) at each of the following constant temperatures: 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40°C. The time spent in each instar and survival was recorded. Developmental rate increased with temperature from 15 to 30°C for all instars, then declined again at higher temperatures. Nymphal survival was lower at 35°C than between 15 and 30°C for all instars, and first instars placed at 5, 10, and 40°C all died without molting. This suggests that L. delicatula survival and development may be affected in the Southern United States by high temperatures and developmental delays will occur under cool spring conditions. The lower developmental threshold was found to be 13.00 ± 0.42°C for first instars, 12.43 ± 2.09°C for second instars, 8.48 ± 2.99°C for third instars, and 6.29 ± 2.12°C for fourth instars. The degree-day (DD) requirement for nymphs in the previous instar to complete development to reach the second instar, third instar, fourth instar, and adult was 166.61, 208.75, 410.49, and 620.07 DD (base varied), respectively. These results provide key data to support the development of phenology models and help identify the potential range of L. delicatula in North America.

The temperature of the surrounding environment has a major influence on ectotherms, such as insects, and can impact physiology, development, and growth. As insects tend to be adapted for the climate in their native range, exposure to temperatures outside of this range in invaded habitats can lead to increased mortality and poorer development during the establishment phase. Estimating the upper and lower thresholds for development and determining the temperature ranges near those thresholds at which the insect starts showing signs of stress, can teach us much about the potential geographic range the insect can invade. With the economic and ecological risk posed by many exotic insects, it can be crucial to look at their response to temperature in order to get a sense of the abiotic constraints that may define their range and provide the timing of stages for deployment of management and monitoring options.

The spotted lanternfly, Lycorma delicatula (White) (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae), an invasive species native to China, India, and Vietnam, was first reported in North America in 2014 in Berks County, Pennsylvania (Barringer et al. 2015). Since then, its range in North America has expanded to include Delaware, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia and it has also been intercepted in additional states (Lee et al. 2019). Lycorma delicatula is currently univoltine and begins to emerge in late April in North America and has four nymphal instars. The first three instars are black and white in coloration while the fourth instar changes to red, black, and white (Dara et al. 2015). Adults tend to appear around mid-July and lay eggs from early September until the first frost. These eggs then overwinter. Both nymphs and adults feed from the phloem of plants, with 172 identified host plant species (Barringer and Ciafré 2020). Despite its diverse host range, it is heavily associated with the invasive tree of heaven, Ailanthus altissima (Miller) (Sapindales: Simaroubaceae), which is one of its preferred hosts and is abundant in North America (Dara et al. 2015).

The broad host range of L. delicatula includes several major agricultural commodities including grapes (Vitis spp. L. (Vitales: Vitaceae)), which can host all stages of the insect, posing a major economic risk to the wine grape and table grape industry (Lee et al. 2019). Their full impact to the tree fruit industry is currently unknown. Many trees that are found in forests, such as Juglans nigra (L.) (Fagales: Juglandaceae), are also at risk (Lee et al. 2019). Lycorma delicatula damages plants through feeding, which can cause dieback and wilting. Furthermore, while feeding, they also exudes excess sugar from their food source as honeydew that facilitates sooty mold growth, which interferes with photosynthesis if it occurs on foliage (Kim et al. 2013). This honeydew is attractive to Vespula spp. Panzer (Hymenoptera: Vespidae), which can pose risks to humans at locations where they are abundant (Dara et al. 2015). In addition, L. delicatula tend to aggregate in large numbers as adults on street trees and other landscape plants making them a nuisance pest in addition to being an agricultural and forestry pest (Lee et al. 2019).

As L. delicatula spreads through the northeastern United States, it is important to discern what other regions of the country are likely to support populations. One method of understanding the effect of temperature on an organism is by using degree-days (DD), which are the accumulated number of degrees per day between the upper (Tmax) and lower (Tmin) developmental threshold of that organism (Baskervi and Emin 1969). The higher the temperature is above the Tmin; the less time is required for the insect to accumulate enough DD to reach the next stage in its development. DD can be estimated once the Tmax and Tmin of an insect is known along with the amount of time it spends in each instar at various temperatures.

Previous research has followed nymphal development of L. delicatula on Virginia creeper, Parthenocissus quinquefolia (L.) (Vitales: Vitaceae), at room temperature (assumed to be slightly above 20°C) and found the duration for first, second, third, and fourth instars was 18.8, 20.9, 20.8, and 22.2 d, respectively (Park et al. 2009). A more recent study looked at its DD requirements using phenology models based on field data from Pennsylvania in 2017; however, for this study, the Tmin for L. delicatula was arbitrarily set at 10°C (Liu 2019). The lack of a Tmin for each instar makes it difficult to use previously found DD requirements for monitoring. Furthermore, past studies did not evaluate its developmental rate at a variety of different temperatures and thus, that information is still needed in order to discern their DD requirements.

Good phenology models based on the responses of L. delicatula to a broad range of temperatures are vital to determining its potential range across North America, as well as for predicting when monitoring and/or application of control methods needs to occur. The information obtained from these models will also help develop protocols for rearing large numbers of L. delicatula for use in bioassays or biological control rearing.

The objectives of this study were to 1) examine how temperature affects the instar specific survival of nymphs, 2) calculate the developmental rate and temperature thresholds for each instar, and 3) to estimate instar-specific DD requirements.

Materials and Methods

Source Populations

In total, 164 L. delicatula egg masses were collected from eight different sites in Pennsylvania (Table 1). Egg masses were imported into the Forest Service quarantine laboratory in Ansonia, CT under a valid permit on 5 April 2019 and 16 October 2019. The 96 egg masses collected in April were held individually in 60 × 15 mm petri dishes (Falcon 351007, Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ) at 10°C until incubation on 13 May 2019 at 25°C and 60 % RH with a photoperiod of 16:8 (L:D) h to initiate hatch. The 68 egg masses collected in October 2019 were used to supplement the supply of fourth instars used in a later part of the study (as described subsequently). Hatch used in the fourth instar cage rearing came from egg masses that were held at 5°C (26 egg masses) or 10°C (37 egg masses) for 84 d followed by incubation at 25°C as well as from egg masses that were held at a constant 15°C (4 egg masses) for the entire duration, all with a photoperiod of 16:8 (L:D) h. Voucher specimens of adult L. delicatula were deposited at the Entomology Division, Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, New Haven, CT.

Approximate location (latitude and longitude), collection date, and hosts from which the egg masses of spotted lanternfly used in this study were obtained

| Collection location . | Collection date . | Host (number of masses) . | Latitude . | Longitude . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bally, PA | 10 Nov. 2018 | Acer saccharinum (L.) (Sapindales: Sapindaceae) (7) | 40.39ºN | 75.59ºW |

| Audubon, PA | 30 Mar. 2019 | Ailanthus altissima (Miller) (Sapindales: Simaroubaceae) (11), Prunus serotina (Ehrhart) (Rosales: Rosaceae) (6) | 40.12ºN | 75.42ºW |

| Audubon, PA | 30 Mar. 2019 | Acer rubrum (L.) (Sapindales: Sapindaceae) (12), Pinus strobus (L.) (5) | 40.12ºN | 75.42ºW |

| Wyomissing, PA | 2 April 2019 | Acer rubrum (L.) (25) | 40.35ºN | 75.99ºW |

| Pennsburg, PA | 4 April 2019 | Acer saccharinum (L.) (30) | 40.36ºN | 75.52ºW |

| Hellertown, PA | 15 Oct. 2019 | Acer negundo (L.) (Sapindales: Sapindaceae) (1), Malus domestica (Rosales: Rosaceae), (Borkhausen) (1), Ailanthus altisima (Miller) (6) | 40.58ºN | 75.34ºW |

| Whitehall township | 15 Oct. 2019 | Ailanthus altisima (Miller) (6) | 40.67ºN | 75.51ºW |

| Pennsburg, PA | 16 Oct. 2019 | Ailanthus altisima (Miller) (53) | 40.41ºN | 75.48ºW |

| Collection location . | Collection date . | Host (number of masses) . | Latitude . | Longitude . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bally, PA | 10 Nov. 2018 | Acer saccharinum (L.) (Sapindales: Sapindaceae) (7) | 40.39ºN | 75.59ºW |

| Audubon, PA | 30 Mar. 2019 | Ailanthus altissima (Miller) (Sapindales: Simaroubaceae) (11), Prunus serotina (Ehrhart) (Rosales: Rosaceae) (6) | 40.12ºN | 75.42ºW |

| Audubon, PA | 30 Mar. 2019 | Acer rubrum (L.) (Sapindales: Sapindaceae) (12), Pinus strobus (L.) (5) | 40.12ºN | 75.42ºW |

| Wyomissing, PA | 2 April 2019 | Acer rubrum (L.) (25) | 40.35ºN | 75.99ºW |

| Pennsburg, PA | 4 April 2019 | Acer saccharinum (L.) (30) | 40.36ºN | 75.52ºW |

| Hellertown, PA | 15 Oct. 2019 | Acer negundo (L.) (Sapindales: Sapindaceae) (1), Malus domestica (Rosales: Rosaceae), (Borkhausen) (1), Ailanthus altisima (Miller) (6) | 40.58ºN | 75.34ºW |

| Whitehall township | 15 Oct. 2019 | Ailanthus altisima (Miller) (6) | 40.67ºN | 75.51ºW |

| Pennsburg, PA | 16 Oct. 2019 | Ailanthus altisima (Miller) (53) | 40.41ºN | 75.48ºW |

Approximate location (latitude and longitude), collection date, and hosts from which the egg masses of spotted lanternfly used in this study were obtained

| Collection location . | Collection date . | Host (number of masses) . | Latitude . | Longitude . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bally, PA | 10 Nov. 2018 | Acer saccharinum (L.) (Sapindales: Sapindaceae) (7) | 40.39ºN | 75.59ºW |

| Audubon, PA | 30 Mar. 2019 | Ailanthus altissima (Miller) (Sapindales: Simaroubaceae) (11), Prunus serotina (Ehrhart) (Rosales: Rosaceae) (6) | 40.12ºN | 75.42ºW |

| Audubon, PA | 30 Mar. 2019 | Acer rubrum (L.) (Sapindales: Sapindaceae) (12), Pinus strobus (L.) (5) | 40.12ºN | 75.42ºW |

| Wyomissing, PA | 2 April 2019 | Acer rubrum (L.) (25) | 40.35ºN | 75.99ºW |

| Pennsburg, PA | 4 April 2019 | Acer saccharinum (L.) (30) | 40.36ºN | 75.52ºW |

| Hellertown, PA | 15 Oct. 2019 | Acer negundo (L.) (Sapindales: Sapindaceae) (1), Malus domestica (Rosales: Rosaceae), (Borkhausen) (1), Ailanthus altisima (Miller) (6) | 40.58ºN | 75.34ºW |

| Whitehall township | 15 Oct. 2019 | Ailanthus altisima (Miller) (6) | 40.67ºN | 75.51ºW |

| Pennsburg, PA | 16 Oct. 2019 | Ailanthus altisima (Miller) (53) | 40.41ºN | 75.48ºW |

| Collection location . | Collection date . | Host (number of masses) . | Latitude . | Longitude . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bally, PA | 10 Nov. 2018 | Acer saccharinum (L.) (Sapindales: Sapindaceae) (7) | 40.39ºN | 75.59ºW |

| Audubon, PA | 30 Mar. 2019 | Ailanthus altissima (Miller) (Sapindales: Simaroubaceae) (11), Prunus serotina (Ehrhart) (Rosales: Rosaceae) (6) | 40.12ºN | 75.42ºW |

| Audubon, PA | 30 Mar. 2019 | Acer rubrum (L.) (Sapindales: Sapindaceae) (12), Pinus strobus (L.) (5) | 40.12ºN | 75.42ºW |

| Wyomissing, PA | 2 April 2019 | Acer rubrum (L.) (25) | 40.35ºN | 75.99ºW |

| Pennsburg, PA | 4 April 2019 | Acer saccharinum (L.) (30) | 40.36ºN | 75.52ºW |

| Hellertown, PA | 15 Oct. 2019 | Acer negundo (L.) (Sapindales: Sapindaceae) (1), Malus domestica (Rosales: Rosaceae), (Borkhausen) (1), Ailanthus altisima (Miller) (6) | 40.58ºN | 75.34ºW |

| Whitehall township | 15 Oct. 2019 | Ailanthus altisima (Miller) (6) | 40.67ºN | 75.51ºW |

| Pennsburg, PA | 16 Oct. 2019 | Ailanthus altisima (Miller) (53) | 40.41ºN | 75.48ºW |

Nymphal Rearing at Different Temperatures

Rearing tubes were constructed from a 61.0 cm long section of 10.3 cm diameter thin-walled shipping tubes with clear caps (PRT.028-4.050 and PCC4.000, Cleartec Packaging, Park Hills, MO). Three mesh openings were added to each tube: two 10.2 × 2.5 cm openings in the side of the tube at 15.2 and 25.4 cm from the top along opposite sides, and a 5.1 × 5.1 cm opening in the middle of the cap(Fig. 1). Ailanthus altissima plants were grown from seeds collected from trees in Morgantown, WV in October 2018. Seeds were initially planted in Jiffy Plugs and then transferred to tree pots measuring 7.6 × 7.6 × 20.3 cm (CN-SS-TP-308, Greenhouse Megastore, Danville, IL) filled with soil (Premier BK25, Promix M, Premier Horticultural Inc., Quakertown, PA) after sprouting. The A. altissima seedlings were provided Osmocote fertilizer (ICL Specialty Fertilizers, Summerville, SC) when first potted and monthly thereafter. A quart-mixing cup (KUS 932, TCP Global, San Diego, CA) was used at the bottom of the tube to hold the potted 30–45 cm tall A. altissima plant.

Upon hatching, 20 nymphs that hatched the same day were placed in a rearing tube containing a single potted A. altissima plant. Six rearing tubes containing first instar L. delicatula (120 total nymphs per treatment) were placed in growth chambers at each of the following temperatures: 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, and 35°C. Three shorter rearing tubes (40.0 cm with mesh openings at 7.6 and 19.1 cm from the top) were placed at 5 and 40°C (total of 60 nymphs per treatment). These smaller tubes were needed since the space available in the chambers running those temperatures was much more limited. All chambers had a chart recorder that was regularly calibrated to check for accuracy of temperature and humidity set points in the chambers. The photoperiod in all the chambers was 16:8 (L: D) h and the humidity was between 60 and 80% RH for tempertures 5–30°C and 40–50% RH for tempertures 35–40°C. The differing humidities were because only the 20 and 25°C chambers had humidity controls while the humidity in the other chambers was maintained by placing open bins of water in the bottom.

Nymphs were monitored daily for survival and molting (confirmed by a cast skin). Once molted, the new instars were relocated to a freshly prepared rearing tube with others that molted the same day for that temperature treatment. A maximum of 16 second instars and six third instars were put in a tube, so in some cases more than one tube was setup each day. Dead nymphs were regularly removed from the tubes in order to maintain hygiene. This was repeated until nymphs reached the fourth instar, where they were held singly and a fresh concord grape (Vitis labrusca L. (Vitales: Vitaceae)) vine section without leaves in a water tube was also added to the rearing tube each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, in order to provide an alternative food source. Plants were changed regularly (more frequently at higher temperatures and/or larger instars) to reduce potential stress caused by overfeeding on a stem. Plants were changed every 28 d for first and second instars. For third instars, plants were changed every 21 d at 20 and 25°C, every 14 d at 30°C, and every 10 d at 35°C. For fourth instars, plants were changed every 7 d. Plants were watered from the bottom without opening the tubes as needed to maintain soil moisture.

Nymphal Rearing to Get Temperature Responses for Fourth Instars in Cages

Due to low survival of the fourth instar in the first part of this study, the number of fourth instars that became adults was limited as only two (one male and one female) and five (all males) individuals at 25 and 30°C, respectively. In order to augment the study, 100 first instars that hatched from the egg masses collected in October 2019 were placed in 32.5 × 32.5 × 77.0 cm mesh cages (BugDorm 4S3074, MegaView Science Co., Ltd, Taichung, Taiwan) containing 1–2 60 cm tall potted A. altissima plants. In total, 10 cages were setup over a 22-d period. As nymphs molted to the second instar, they were moved to a larger mesh cage (60 × 60 × 120 cm; BugDorm 6S620, MegaView Science Co., Ltd, Taichung, Taiwan) with 2–3 100 cm tall potted A. altissima plants. A total of six cages, each with a maximum of 100 second instars, were setup over a 21-d period. New third instars were moved to new large cages (same setup as used for the second instars) with four 100 cm tall potted A. altissima plants and new plants were rotated in weekly. A total of eight cages with a maximum of 60 third instars each were setup over a 15-d period of time. These cages were checked daily for new fourth instars and 4–6 nymphs that molted the same day were placed in small cages (same as used for the first instars) with 50–60 cm tall A. altissima plants. Cages containing the fourth instars were assigned to a temperature (15, 20, 25, 30, or 35°C) in sequential order from lowest to highest temperature to ensure that all temperature treatments had nymphs from across the 23-d period that molts occurred. In total, 30 fourth instars were placed at each temperature and were monitored daily for mortality and molting (confirmed by a cast skin). Each cage started with two trees and an additional tree was added weekly (20–35°C) or every 10 d (15°C). Once there were four trees, the oldest tree was removed when a new tree was added. Trees were watered daily. When a newly molted adult was found in the cage it was sexed, weighed, and then frozen. If the adult had not finished sclerotization, it was left at room temperature overnight, then frozen. Three measurements were made on each frozen adult: fore wing length, fore wing width, and hind tibia length.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute 2015). The normality of the data was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk and the Anderson–Darling tests. When the data did not fit a normal distribution PROC UNIVARIATE was used to assess the distributional fit of the data to a gamma distribution. The gamma distribution accommodates long right-skewed tails, which are common in this type of data.

PROC GLIMMIX was used to evaluate the fixed effect of temperature on the duration of each of the first three instars. Since the sex of the adults was known the fixed effects of sex and the interaction between sex and temperature were added to the model to evaluate effects on the duration of the fourth instar. Adult body weight (g), fore wing length (mm) and width (mm), and hind tibia length (mm) were evaluated for both sexes separately using the temperature as a fixed effect. Adults obtained from both the first (tube-based) and supplemental (cage rearing) data sets were included in the analysis. The container the individuals were reared in was treated as a random effect in all models to account for between container effects. Each model was fitted to a gamma distribution with a log link function because the response variables had long right tails. When interaction effects were not significant the model was reduced to the significant effects and re-run. Differences among means were determined using the Tukey–Kramer post hoc analysis and α = 0.05. For each model, residuals were evaluated for normality and the homogeneity of variance was assessed using Levene’s test. This ensures that the assumptions for the statistical tests have been met or appropriate steps have been taken to account for unequal variance.

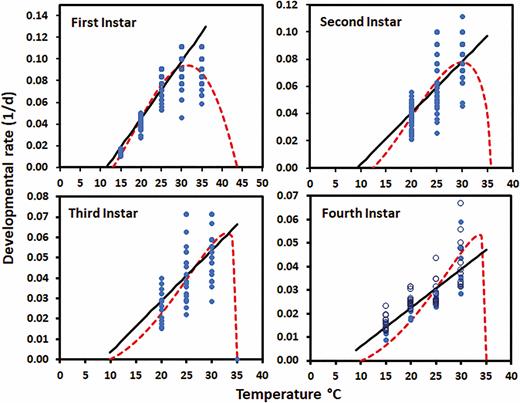

The relationship between temperature and developmental rate for each instar was estimated by fitting both a linear model (developmental rate = a + bT) using Statistix (2013) and the Briere non-linear model using PROC NLIN and Marquardt convergence method (Briere et al. 1999, SAS Institute 2015) (Table 3). Temperatures near the Tmin or above the optimal temperature (temperature at which development was fastest) were included in the Briere models but were not included in the linear models. The Tmin for the linear model was estimated as –a/b where a and b were estimated by least squares regression (Statistix 2013). The standard error for the Tmin estimated using the linear model was calculated using the formula given in Campbell et al. (1974). The Briere model is: developmental rate = a × T × (T − Tmin) × ((Tmax − T)(1÷b)). In the model Tmin is the lower developmental threshold, a is an empirical constant, and b determines the inflection point and steepness of the decline when temperatures (T) approach the upper developmental threshold (Tmax). The nonlinear relationship (Briere et al. 1999) was evaluated for all instars, but not ultimately used for the last two instars due to its poor fit to the data (based on adjusted r2 and a visual comparison to the data), especially near the optimal temperature. The optimum temperature for the Briere model was calculated by equating the first derivative to zero and solving for t. The Tmin used in subsequent analyses was from the Briere model for the first two instars and from the linear model for the last two instars.

Parameter values for linear and nonlinear models used to describe the relationship between temperature (°C) and developmental rate of Lycorma delicatula nymphs

| Development Period . | Temperature range . | Model . | a . | b . | T min . | T max . | n . | Adj R 2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days in first instar | 10 to 30 | Linear | 0.00529 ± 0.000129 | -0.06069 ± 0.00317 | 11.47 ± 0.42 | NA | 272 | 0.8613 |

| 10 to 35 | Briere | 0.000011 ± 0.0000009 | 0.9335 ± 0.2035 | 13.05 ± 0.42 | 43.81 ± 2.59 | 322 | 0.8699 | |

| Days in second instar | 20 to 30 | Linear | 0.00379 ± 0.000307 | -0.03526 ± 0.00781 | 9.30 ± 1.35 | NA | 180 | 0.4581 |

| 20 to 30 | Briere | 0.000062 ± 0.000016 | 1.9766 ± 0.6338 | 12.43 ± 2.09 | 35.58 ± 0.82 | 180 | 0.5124 | |

| Days in third Instar | 20 to 30 | Linear | 0.00250 ± 0.000419 | -0.02121 ± 0.01104 | 8.48 ± 2.99 | NA | 59 | 0.3692 |

| 20 to 35 | Briere | 0.000073 ± 0.000014 | 6.4742 ± 12.3743 | 9.87 ± 8.76 | 35.00 ± 0.00 | 60 | 0.3704 | |

| Days in fourth Instar | 15 to 30 | Linear | 0.00164 ± 0.000013 | -0.00103 ± 0.00299 | 6.29 ± 2.12 | NA | 87 | 0.6470 |

| 15 to 35 | Briere | 0.00065 ± 0.000011 | 9.6873 ± 12.8048 | 10.00 ± 2.65 | 35.00 ± 0.00 | 88 | 0.4136 |

| Development Period . | Temperature range . | Model . | a . | b . | T min . | T max . | n . | Adj R 2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days in first instar | 10 to 30 | Linear | 0.00529 ± 0.000129 | -0.06069 ± 0.00317 | 11.47 ± 0.42 | NA | 272 | 0.8613 |

| 10 to 35 | Briere | 0.000011 ± 0.0000009 | 0.9335 ± 0.2035 | 13.05 ± 0.42 | 43.81 ± 2.59 | 322 | 0.8699 | |

| Days in second instar | 20 to 30 | Linear | 0.00379 ± 0.000307 | -0.03526 ± 0.00781 | 9.30 ± 1.35 | NA | 180 | 0.4581 |

| 20 to 30 | Briere | 0.000062 ± 0.000016 | 1.9766 ± 0.6338 | 12.43 ± 2.09 | 35.58 ± 0.82 | 180 | 0.5124 | |

| Days in third Instar | 20 to 30 | Linear | 0.00250 ± 0.000419 | -0.02121 ± 0.01104 | 8.48 ± 2.99 | NA | 59 | 0.3692 |

| 20 to 35 | Briere | 0.000073 ± 0.000014 | 6.4742 ± 12.3743 | 9.87 ± 8.76 | 35.00 ± 0.00 | 60 | 0.3704 | |

| Days in fourth Instar | 15 to 30 | Linear | 0.00164 ± 0.000013 | -0.00103 ± 0.00299 | 6.29 ± 2.12 | NA | 87 | 0.6470 |

| 15 to 35 | Briere | 0.00065 ± 0.000011 | 9.6873 ± 12.8048 | 10.00 ± 2.65 | 35.00 ± 0.00 | 88 | 0.4136 |

See Materials and Methods for details of the analysis.

Parameter values for linear and nonlinear models used to describe the relationship between temperature (°C) and developmental rate of Lycorma delicatula nymphs

| Development Period . | Temperature range . | Model . | a . | b . | T min . | T max . | n . | Adj R 2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days in first instar | 10 to 30 | Linear | 0.00529 ± 0.000129 | -0.06069 ± 0.00317 | 11.47 ± 0.42 | NA | 272 | 0.8613 |

| 10 to 35 | Briere | 0.000011 ± 0.0000009 | 0.9335 ± 0.2035 | 13.05 ± 0.42 | 43.81 ± 2.59 | 322 | 0.8699 | |

| Days in second instar | 20 to 30 | Linear | 0.00379 ± 0.000307 | -0.03526 ± 0.00781 | 9.30 ± 1.35 | NA | 180 | 0.4581 |

| 20 to 30 | Briere | 0.000062 ± 0.000016 | 1.9766 ± 0.6338 | 12.43 ± 2.09 | 35.58 ± 0.82 | 180 | 0.5124 | |

| Days in third Instar | 20 to 30 | Linear | 0.00250 ± 0.000419 | -0.02121 ± 0.01104 | 8.48 ± 2.99 | NA | 59 | 0.3692 |

| 20 to 35 | Briere | 0.000073 ± 0.000014 | 6.4742 ± 12.3743 | 9.87 ± 8.76 | 35.00 ± 0.00 | 60 | 0.3704 | |

| Days in fourth Instar | 15 to 30 | Linear | 0.00164 ± 0.000013 | -0.00103 ± 0.00299 | 6.29 ± 2.12 | NA | 87 | 0.6470 |

| 15 to 35 | Briere | 0.00065 ± 0.000011 | 9.6873 ± 12.8048 | 10.00 ± 2.65 | 35.00 ± 0.00 | 88 | 0.4136 |

| Development Period . | Temperature range . | Model . | a . | b . | T min . | T max . | n . | Adj R 2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days in first instar | 10 to 30 | Linear | 0.00529 ± 0.000129 | -0.06069 ± 0.00317 | 11.47 ± 0.42 | NA | 272 | 0.8613 |

| 10 to 35 | Briere | 0.000011 ± 0.0000009 | 0.9335 ± 0.2035 | 13.05 ± 0.42 | 43.81 ± 2.59 | 322 | 0.8699 | |

| Days in second instar | 20 to 30 | Linear | 0.00379 ± 0.000307 | -0.03526 ± 0.00781 | 9.30 ± 1.35 | NA | 180 | 0.4581 |

| 20 to 30 | Briere | 0.000062 ± 0.000016 | 1.9766 ± 0.6338 | 12.43 ± 2.09 | 35.58 ± 0.82 | 180 | 0.5124 | |

| Days in third Instar | 20 to 30 | Linear | 0.00250 ± 0.000419 | -0.02121 ± 0.01104 | 8.48 ± 2.99 | NA | 59 | 0.3692 |

| 20 to 35 | Briere | 0.000073 ± 0.000014 | 6.4742 ± 12.3743 | 9.87 ± 8.76 | 35.00 ± 0.00 | 60 | 0.3704 | |

| Days in fourth Instar | 15 to 30 | Linear | 0.00164 ± 0.000013 | -0.00103 ± 0.00299 | 6.29 ± 2.12 | NA | 87 | 0.6470 |

| 15 to 35 | Briere | 0.00065 ± 0.000011 | 9.6873 ± 12.8048 | 10.00 ± 2.65 | 35.00 ± 0.00 | 88 | 0.4136 |

See Materials and Methods for details of the analysis.

DD requirements for each instar were estimated using the function: DD = [constant temperature – TL] × Dt, where Dt is the total number of days required by individual nymph to reach the next instar. The relationships between accumulated DD and cumulative proportion of individuals to reach each instar were estimated using the Gompertz function, P = exp [- exp (- b * DD + a] (Brown and Mayer 1988) with the Marquardt convergence method. In the function a and b are constants that determine the shape of the curve. Accumulated DD required by 10, 50, and 90% of nymphs to reach each instar were calculated.

Results

Survival

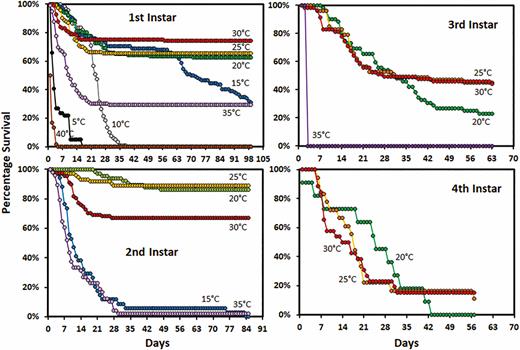

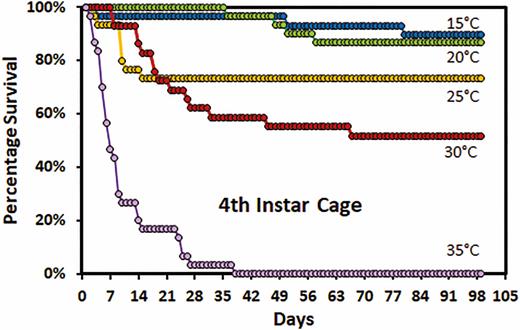

At 10°C, most first instar nymphs died between 21 and 35 d (mean 22.7 ± 0.6 d) (Fig. 2). At 40°C, the first instar nymphs all died in the first 5 d (1.8 ± 0.1 d). Mean survival of first instar nymphs at 5°C was 5.1 ± 0.6 d, however, some survived longer than 2 wk. At 35°C, first instars that were unable to molt, died within 35 d (mean 8.6 ± 0.7 d). First instar survival at 15 to 30°C was similar for the first 35 d. However, at 15°C mortality increased again at 63 d. In the second instar, mortality for 15 and 35°C was similar except that a very small percentage at 15°C survived for much longer (Fig. 2). Greater than 70% of the first and second instars held at 20–30°C were able to molt (Fig. 2). Survival of second instars at 30°C was lower than at 20 and 25°C. In rearing tubes, fewer than 50% of the third or fourth instars were able to molt. The survival of fourth instars was higher in cages than in the rearing tubes. Survival of fourth instars in cages was similar at 15 and 20°C (Fig. 3). More males than females survived to complete the fourth instar at both 15 and 30°C. In cages, greater than 70% of fourth instars at 15, 20, and 25°C were able to molt to adult.

Survivorship curves for Lycorma delicatula nymphs reared in tubes by instar and temperature.

Survivorship curves for fourth instar Lycorma delicatula nymphs reared in cages by temperature.

Developmental Rate and Temperature Thresholds for Each Instar

The mean time (days) spent in each of the four instars decreased as the temperature increased from 15 or 20 to 30°C and then began to increase again at higher temperatures for the first and second instars (Table 2). There were significant differences between some of the temperatures for days between molts, but it varied between instars. When the number of days spent in the fourth instar for both sexes was evaluated, temperature had significant effects (F = 33.30; df = 3, 22.15; P < 0.0001) and sex (F = 20.08; df = 1, 73.40; P < 0.0001), while the interaction between the two did not (F = 0.25; df = 3, 71.36; P = 0.8630), although, females tended to spend longer in the fourth instar than males. The parameter values for the linear and Briere models used to describe the relationship between temperature and developmental rate are given in Table 3 and the lines/curves are plotted with the raw data in Fig. 4. The Briere model was a good fit for the data for the first and second instars, but the linear model (excluding temperatures above the optimal) was better for third and fourth instars. Another reason for choosing the linear model for these instars was that data for temperatures above the optimum was lacking for the third instar and only one temperature that resulted in 100% mortality was evaluated above the optimum for the fourth instar. The fit was evaluated both based on adjusted r2 and by a visual examination of the fit. The Tmin for development decreased with instar (using the model that was better for each instar) and the upper threshold for development was highest for the first instar at 43.81 ± 2.59°C and then remained close to 35°C for the other instars (Fig. 4). The optimal temperature for the first and second instars were 31.4 and 30.0°C, respectively.

Mean [± SE (n)] time spent (days) by Lycorma delicatula in each instar at different temperatures

| Instar . | Temperature (°C) . | . | . | . | . | Statistics . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 15 . | 20 . | 25 . | 30 . | 35 . | F . | df . | P . |

| First | 71.3 ± 2.57a (34) | 23.4 ± 0.73b (71) | 12.6 ± 0.39c (79) | 10.9 ± 0.33cd (89) | 11.7 ± 0.41d (49) | 519.9 | 4, 25.31 | <0.0001 |

| Second | NA | 24.0 ± 1.92a (56) | 20.2 ± 1.70a (65) | 14.2 ± 1.25b (59) | 27 ab (1) | 6.76 | 3, 24.01 | 0.0018 |

| Third | NA | 40.4 ± 4.38a (14) | 24.6 ± 2.03b (21) | 21.0 ± 1.95b (26) | NA | 11.09 | 2, 27.64 | 0.0003 |

| Fourth males | 64.6 ± 4.93a (14) | 39.5 ± 2.93b (14) | 34.0 ± 2.29b (13) | 24.2 ± 1.67c (12) | NA | 31.15 | 3, 17.28 | <0.0001 |

| Fourth females | 85.5 ± 8.04a (7) | 50.1 ± 4.21b (12) | 38.6 ± 3.25bc (10) | 28.4 ± 3.70c (7) | NA | 20.16 | 3, 11.77 | <0.0001 |

| Instar . | Temperature (°C) . | . | . | . | . | Statistics . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 15 . | 20 . | 25 . | 30 . | 35 . | F . | df . | P . |

| First | 71.3 ± 2.57a (34) | 23.4 ± 0.73b (71) | 12.6 ± 0.39c (79) | 10.9 ± 0.33cd (89) | 11.7 ± 0.41d (49) | 519.9 | 4, 25.31 | <0.0001 |

| Second | NA | 24.0 ± 1.92a (56) | 20.2 ± 1.70a (65) | 14.2 ± 1.25b (59) | 27 ab (1) | 6.76 | 3, 24.01 | 0.0018 |

| Third | NA | 40.4 ± 4.38a (14) | 24.6 ± 2.03b (21) | 21.0 ± 1.95b (26) | NA | 11.09 | 2, 27.64 | 0.0003 |

| Fourth males | 64.6 ± 4.93a (14) | 39.5 ± 2.93b (14) | 34.0 ± 2.29b (13) | 24.2 ± 1.67c (12) | NA | 31.15 | 3, 17.28 | <0.0001 |

| Fourth females | 85.5 ± 8.04a (7) | 50.1 ± 4.21b (12) | 38.6 ± 3.25bc (10) | 28.4 ± 3.70c (7) | NA | 20.16 | 3, 11.77 | <0.0001 |

Means within a row followed by a different letter are significantly different from each other at P < 0.05 using Tukey–Kramer post hoc test. Sample size (n) is the number of survivors.

Mean [± SE (n)] time spent (days) by Lycorma delicatula in each instar at different temperatures

| Instar . | Temperature (°C) . | . | . | . | . | Statistics . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 15 . | 20 . | 25 . | 30 . | 35 . | F . | df . | P . |

| First | 71.3 ± 2.57a (34) | 23.4 ± 0.73b (71) | 12.6 ± 0.39c (79) | 10.9 ± 0.33cd (89) | 11.7 ± 0.41d (49) | 519.9 | 4, 25.31 | <0.0001 |

| Second | NA | 24.0 ± 1.92a (56) | 20.2 ± 1.70a (65) | 14.2 ± 1.25b (59) | 27 ab (1) | 6.76 | 3, 24.01 | 0.0018 |

| Third | NA | 40.4 ± 4.38a (14) | 24.6 ± 2.03b (21) | 21.0 ± 1.95b (26) | NA | 11.09 | 2, 27.64 | 0.0003 |

| Fourth males | 64.6 ± 4.93a (14) | 39.5 ± 2.93b (14) | 34.0 ± 2.29b (13) | 24.2 ± 1.67c (12) | NA | 31.15 | 3, 17.28 | <0.0001 |

| Fourth females | 85.5 ± 8.04a (7) | 50.1 ± 4.21b (12) | 38.6 ± 3.25bc (10) | 28.4 ± 3.70c (7) | NA | 20.16 | 3, 11.77 | <0.0001 |

| Instar . | Temperature (°C) . | . | . | . | . | Statistics . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 15 . | 20 . | 25 . | 30 . | 35 . | F . | df . | P . |

| First | 71.3 ± 2.57a (34) | 23.4 ± 0.73b (71) | 12.6 ± 0.39c (79) | 10.9 ± 0.33cd (89) | 11.7 ± 0.41d (49) | 519.9 | 4, 25.31 | <0.0001 |

| Second | NA | 24.0 ± 1.92a (56) | 20.2 ± 1.70a (65) | 14.2 ± 1.25b (59) | 27 ab (1) | 6.76 | 3, 24.01 | 0.0018 |

| Third | NA | 40.4 ± 4.38a (14) | 24.6 ± 2.03b (21) | 21.0 ± 1.95b (26) | NA | 11.09 | 2, 27.64 | 0.0003 |

| Fourth males | 64.6 ± 4.93a (14) | 39.5 ± 2.93b (14) | 34.0 ± 2.29b (13) | 24.2 ± 1.67c (12) | NA | 31.15 | 3, 17.28 | <0.0001 |

| Fourth females | 85.5 ± 8.04a (7) | 50.1 ± 4.21b (12) | 38.6 ± 3.25bc (10) | 28.4 ± 3.70c (7) | NA | 20.16 | 3, 11.77 | <0.0001 |

Means within a row followed by a different letter are significantly different from each other at P < 0.05 using Tukey–Kramer post hoc test. Sample size (n) is the number of survivors.

Relationship between temperature and the developmental rates (1/d) for Lycorma delicatula nymphs by instar. Dots represent the observed individual values for each nymph (fourth instar open female and closed male). The solid line is the linear and dashed the Briere predicted relationships between developmental rate and temperature.

Estimated DD Requirements

Using the estimated developmental thresholds, the DD requirements for each of the instars were estimated using the Gompertz function (Table 4 and Fig. 5). DD requirements increased with each instar, partly due to the decreasing lower developmental threshold. The difference in the mean number of DD required for 10–90% of the population to reach the next life stage increased between the first and third instars, but was similar for third and fourth instars (92, 148, 335, and 364 DD for the first, second, third, and fourth instars, respectively).

Estimated accumulated DD (± SE) required to reach each instar by Lycorma delicatula nymphs for 10, 50, and 90 of the population

| Life stage reached . | Degree-day (± SE) requirement for nymphs (%) to reach different life stages after egg hatch . | . | . | T min . | R 2 Adj . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 10% . | 50% . | 90% . | Used . | . |

| Second instar | 130.77 (130.01–131.49) | 166.61 (166.46 −166.76) | 222.84 (221.34–224.42) | 13.05 | 0.9911 |

| Third instar | 151.31 (150.48–152.12) | 208.75 (208.69 −208.82) | 298.89 (297.46–300.36) | 12.43 | 0.9967 |

| Fourth instar | 280.14 (277.41–282.75) | 410.49 (410.27 −410.72) | 615.03 (610.39–619.89) | 8.48 | 0.993 |

| Adult | 478.33 (481.46–475.04) | 620.07 (619.90–620.25) | 842.49 (837.14–848.10) | 6.29 | 0.9890 |

| Life stage reached . | Degree-day (± SE) requirement for nymphs (%) to reach different life stages after egg hatch . | . | . | T min . | R 2 Adj . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 10% . | 50% . | 90% . | Used . | . |

| Second instar | 130.77 (130.01–131.49) | 166.61 (166.46 −166.76) | 222.84 (221.34–224.42) | 13.05 | 0.9911 |

| Third instar | 151.31 (150.48–152.12) | 208.75 (208.69 −208.82) | 298.89 (297.46–300.36) | 12.43 | 0.9967 |

| Fourth instar | 280.14 (277.41–282.75) | 410.49 (410.27 −410.72) | 615.03 (610.39–619.89) | 8.48 | 0.993 |

| Adult | 478.33 (481.46–475.04) | 620.07 (619.90–620.25) | 842.49 (837.14–848.10) | 6.29 | 0.9890 |

T min = Lower temperature thresholds. R2Adj value is based on the relationship between DD and cumulative proportion attaining each instar using the Gompertz function, P = exp [−exp(−b * DD + a].

Estimated accumulated DD (± SE) required to reach each instar by Lycorma delicatula nymphs for 10, 50, and 90 of the population

| Life stage reached . | Degree-day (± SE) requirement for nymphs (%) to reach different life stages after egg hatch . | . | . | T min . | R 2 Adj . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 10% . | 50% . | 90% . | Used . | . |

| Second instar | 130.77 (130.01–131.49) | 166.61 (166.46 −166.76) | 222.84 (221.34–224.42) | 13.05 | 0.9911 |

| Third instar | 151.31 (150.48–152.12) | 208.75 (208.69 −208.82) | 298.89 (297.46–300.36) | 12.43 | 0.9967 |

| Fourth instar | 280.14 (277.41–282.75) | 410.49 (410.27 −410.72) | 615.03 (610.39–619.89) | 8.48 | 0.993 |

| Adult | 478.33 (481.46–475.04) | 620.07 (619.90–620.25) | 842.49 (837.14–848.10) | 6.29 | 0.9890 |

| Life stage reached . | Degree-day (± SE) requirement for nymphs (%) to reach different life stages after egg hatch . | . | . | T min . | R 2 Adj . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 10% . | 50% . | 90% . | Used . | . |

| Second instar | 130.77 (130.01–131.49) | 166.61 (166.46 −166.76) | 222.84 (221.34–224.42) | 13.05 | 0.9911 |

| Third instar | 151.31 (150.48–152.12) | 208.75 (208.69 −208.82) | 298.89 (297.46–300.36) | 12.43 | 0.9967 |

| Fourth instar | 280.14 (277.41–282.75) | 410.49 (410.27 −410.72) | 615.03 (610.39–619.89) | 8.48 | 0.993 |

| Adult | 478.33 (481.46–475.04) | 620.07 (619.90–620.25) | 842.49 (837.14–848.10) | 6.29 | 0.9890 |

T min = Lower temperature thresholds. R2Adj value is based on the relationship between DD and cumulative proportion attaining each instar using the Gompertz function, P = exp [−exp(−b * DD + a].

![Cumulative proportion of Lycorma delicatula nymphs to compete each instar reared at 15, 20, 25 30, and 35°C over accumulated DD. Open triangles, squares, circles, and diamonds represent first, second, third, and fourth instar individuals, respectively. Solid lines were fitted to cumulative the proportion of individuals using Gompertz function, P = exp[−exp(−bDD + a].](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ee/50/1/10.1093_ee_nvaa155/1/m_nvaa155_fig5.jpeg?Expires=1749043364&Signature=wKp1Dq~PnPRDEYKeWWSGEnayimHqMV5sC~QgFdCAp1M~LzrSP9z4cFjEiJVZBIiWDsoY8~KsX7mzPOsdxgDOve1sEJ~dOe3PP-xB1uasDfFmCIduKGt4wX84hECCyp-DxpGlWNloyBVlVqTN2MMgguyDqdRWFS4tLt~KPaDKWRloWNteDzF4f9dppqxNs8d5bQiEp52PMXAyHN6F-GLy8EH2VU2-V3pY9tu2MZzyG0uL9jefnkSf4NK0TXC4vbGOffm15pNKDVcYtfAMicHuCI5hVyGahebsiVcnPZ9DmwYonCEkMZvfwVBrxEnQfNHWAAP7yHmuhZCHBotARNJpcg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Cumulative proportion of Lycorma delicatula nymphs to compete each instar reared at 15, 20, 25 30, and 35°C over accumulated DD. Open triangles, squares, circles, and diamonds represent first, second, third, and fourth instar individuals, respectively. Solid lines were fitted to cumulative the proportion of individuals using Gompertz function, P = exp[−exp(−bDD + a].

Adult Mass and Morphometrics

Adult weight differed significantly by sex (F = 114.14; df = 1, 74.59; P < 0.0001) but not temperature (F = 0.38; df = 3, 13.41; P = 0.7710) or the interaction between sex and temperature (F = 1.34; df = 3, 72.94; P = 0.2668) with females weighing more than males (Table 5). The length of the hind tibia also differed significantly by sex (F = 47,61; df = 1, 80.63; P < 0.0001) and not temperature (F = 1.57; df = 3, 14.55; P = 0.2396) or the interaction between sex and temperature (F = 0.47; df = 3, 78.88; P = 0.7021) (Table 5). Forewing length was significantly affected by sex (F = 70.56; df = 1, 79.79; P < 0.0001) and temperature (F = 5.22; df = 1, 20.67; P = 0.0077) but not the interaction between the two (F = 2.33; df = 1, 77.54; P = 0.0810). Among males, forewing length of males at 15°C was shorter than for males at all other temperatures. Among females, forewing length of females at 15°C was shorter than for females at all other temperatures (Table 5). Forewing width was significantly affected only by sex (F = 47.39; df = 1, 61.17; P < 0.0001) and temperature (F = 4.18; df = 1, 19.79; P = 0.0191) but not the interaction between the two (F = 0.31; df = 1, 60.58; P = 0.8213. Forewing width of females was wider than that of males (Table 5). Among males, males at both 15 and 30°C had narrower wings than males at 20 and 25°C. At 15°C, some males did not fully expand their wings, resulting in shorter, narrower wings.

Mean [± SE (n)] adult Lycorma delicatula body weight (g), fore wing length (mm) and width (mm), and hind tibia length (mm) at different temperatures

| Sex . | Measure . | Temperature (°C) . | . | . | . | Statistics . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 15 . | 20 . | 25 . | 30 . | F . | df . | P . |

| Male | Weight (g) | 0.118 ± 0.006a (14) | 0.127 ± 0.007a (14) | 0.126 ± 0.007a (12) | 0.112 ± 0.008a (8) | 0.89 | 3, 13.96 | 0.4718 |

| Fore wing length (mm) | 13.7 ± 0.70b (14) | 17.0 ± 0.87a (14) | 17.6 ± 0.78a (13) | 17.2 ± 0.76a (12) | 5.36 | 3, 20.2 | 0.0071 | |

| Fore wing width (mm) | 6.78 ± 0.16b (14) | 7.58 ± 0.18a (14) | 7.58 ± 0.17a (13) | 7.35 ± 0.17ab (12) | 4.77 | 3, 15.82 | 0.0148 | |

| Hind tibia length (mm) | 9.19 ± 0.19a (14) | 9.54 ± 0.19a (14) | 9.45 ± 0.18a (13) | 9.42 ± 0.18a (12) | 0.61 | 3, 14.27 | 0.6189 | |

| Female | Weight (g) | 0.165 ± 0.012a (7) | 0.165 ± 0.011a (12) | 0.173 ± 0.012a (11) | 0.175 ± 0.017a (7) | 0.18 | 3, 9.641 | 0.9058 |

| Fore wing length (mm) | 16.5 ± 0.74b (7) | 19.7 ± 0.77ab (12) | 21.2 ± 0.84a (11) | 21.4 ± 1.17a (7) | 6.99 | 3, 9.187 | 0.0096 | |

| Fore wing width (mm) | 8.09 ± 0.54a (7) | 9.60 ± 0.52a (12) | 9.08 ± 0.51a (11) | 8.81 ± 0.63a (7) | 1.34 | 3, 11.65 | 0.3098 | |

| Hind tibia length (mm) | 9.8 ± 0.41a (7) | 10.5 ± 0.38a (12) | 10.6 ± 0.39a (11) | 10.8 ± 0.58a (7) | 1.08 | 3, 9.935 | 0.3999 |

| Sex . | Measure . | Temperature (°C) . | . | . | . | Statistics . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 15 . | 20 . | 25 . | 30 . | F . | df . | P . |

| Male | Weight (g) | 0.118 ± 0.006a (14) | 0.127 ± 0.007a (14) | 0.126 ± 0.007a (12) | 0.112 ± 0.008a (8) | 0.89 | 3, 13.96 | 0.4718 |

| Fore wing length (mm) | 13.7 ± 0.70b (14) | 17.0 ± 0.87a (14) | 17.6 ± 0.78a (13) | 17.2 ± 0.76a (12) | 5.36 | 3, 20.2 | 0.0071 | |

| Fore wing width (mm) | 6.78 ± 0.16b (14) | 7.58 ± 0.18a (14) | 7.58 ± 0.17a (13) | 7.35 ± 0.17ab (12) | 4.77 | 3, 15.82 | 0.0148 | |

| Hind tibia length (mm) | 9.19 ± 0.19a (14) | 9.54 ± 0.19a (14) | 9.45 ± 0.18a (13) | 9.42 ± 0.18a (12) | 0.61 | 3, 14.27 | 0.6189 | |

| Female | Weight (g) | 0.165 ± 0.012a (7) | 0.165 ± 0.011a (12) | 0.173 ± 0.012a (11) | 0.175 ± 0.017a (7) | 0.18 | 3, 9.641 | 0.9058 |

| Fore wing length (mm) | 16.5 ± 0.74b (7) | 19.7 ± 0.77ab (12) | 21.2 ± 0.84a (11) | 21.4 ± 1.17a (7) | 6.99 | 3, 9.187 | 0.0096 | |

| Fore wing width (mm) | 8.09 ± 0.54a (7) | 9.60 ± 0.52a (12) | 9.08 ± 0.51a (11) | 8.81 ± 0.63a (7) | 1.34 | 3, 11.65 | 0.3098 | |

| Hind tibia length (mm) | 9.8 ± 0.41a (7) | 10.5 ± 0.38a (12) | 10.6 ± 0.39a (11) | 10.8 ± 0.58a (7) | 1.08 | 3, 9.935 | 0.3999 |

Means within a row followed by a different letter are significantly different from each other at P < 0.05 using Tukey–Kramer post hoc test. Sample size (n) is the number of survivors.

Mean [± SE (n)] adult Lycorma delicatula body weight (g), fore wing length (mm) and width (mm), and hind tibia length (mm) at different temperatures

| Sex . | Measure . | Temperature (°C) . | . | . | . | Statistics . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 15 . | 20 . | 25 . | 30 . | F . | df . | P . |

| Male | Weight (g) | 0.118 ± 0.006a (14) | 0.127 ± 0.007a (14) | 0.126 ± 0.007a (12) | 0.112 ± 0.008a (8) | 0.89 | 3, 13.96 | 0.4718 |

| Fore wing length (mm) | 13.7 ± 0.70b (14) | 17.0 ± 0.87a (14) | 17.6 ± 0.78a (13) | 17.2 ± 0.76a (12) | 5.36 | 3, 20.2 | 0.0071 | |

| Fore wing width (mm) | 6.78 ± 0.16b (14) | 7.58 ± 0.18a (14) | 7.58 ± 0.17a (13) | 7.35 ± 0.17ab (12) | 4.77 | 3, 15.82 | 0.0148 | |

| Hind tibia length (mm) | 9.19 ± 0.19a (14) | 9.54 ± 0.19a (14) | 9.45 ± 0.18a (13) | 9.42 ± 0.18a (12) | 0.61 | 3, 14.27 | 0.6189 | |

| Female | Weight (g) | 0.165 ± 0.012a (7) | 0.165 ± 0.011a (12) | 0.173 ± 0.012a (11) | 0.175 ± 0.017a (7) | 0.18 | 3, 9.641 | 0.9058 |

| Fore wing length (mm) | 16.5 ± 0.74b (7) | 19.7 ± 0.77ab (12) | 21.2 ± 0.84a (11) | 21.4 ± 1.17a (7) | 6.99 | 3, 9.187 | 0.0096 | |

| Fore wing width (mm) | 8.09 ± 0.54a (7) | 9.60 ± 0.52a (12) | 9.08 ± 0.51a (11) | 8.81 ± 0.63a (7) | 1.34 | 3, 11.65 | 0.3098 | |

| Hind tibia length (mm) | 9.8 ± 0.41a (7) | 10.5 ± 0.38a (12) | 10.6 ± 0.39a (11) | 10.8 ± 0.58a (7) | 1.08 | 3, 9.935 | 0.3999 |

| Sex . | Measure . | Temperature (°C) . | . | . | . | Statistics . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 15 . | 20 . | 25 . | 30 . | F . | df . | P . |

| Male | Weight (g) | 0.118 ± 0.006a (14) | 0.127 ± 0.007a (14) | 0.126 ± 0.007a (12) | 0.112 ± 0.008a (8) | 0.89 | 3, 13.96 | 0.4718 |

| Fore wing length (mm) | 13.7 ± 0.70b (14) | 17.0 ± 0.87a (14) | 17.6 ± 0.78a (13) | 17.2 ± 0.76a (12) | 5.36 | 3, 20.2 | 0.0071 | |

| Fore wing width (mm) | 6.78 ± 0.16b (14) | 7.58 ± 0.18a (14) | 7.58 ± 0.17a (13) | 7.35 ± 0.17ab (12) | 4.77 | 3, 15.82 | 0.0148 | |

| Hind tibia length (mm) | 9.19 ± 0.19a (14) | 9.54 ± 0.19a (14) | 9.45 ± 0.18a (13) | 9.42 ± 0.18a (12) | 0.61 | 3, 14.27 | 0.6189 | |

| Female | Weight (g) | 0.165 ± 0.012a (7) | 0.165 ± 0.011a (12) | 0.173 ± 0.012a (11) | 0.175 ± 0.017a (7) | 0.18 | 3, 9.641 | 0.9058 |

| Fore wing length (mm) | 16.5 ± 0.74b (7) | 19.7 ± 0.77ab (12) | 21.2 ± 0.84a (11) | 21.4 ± 1.17a (7) | 6.99 | 3, 9.187 | 0.0096 | |

| Fore wing width (mm) | 8.09 ± 0.54a (7) | 9.60 ± 0.52a (12) | 9.08 ± 0.51a (11) | 8.81 ± 0.63a (7) | 1.34 | 3, 11.65 | 0.3098 | |

| Hind tibia length (mm) | 9.8 ± 0.41a (7) | 10.5 ± 0.38a (12) | 10.6 ± 0.39a (11) | 10.8 ± 0.58a (7) | 1.08 | 3, 9.935 | 0.3999 |

Means within a row followed by a different letter are significantly different from each other at P < 0.05 using Tukey–Kramer post hoc test. Sample size (n) is the number of survivors.

Discussion

Temperature had a significant effect on L. delicatula developmental rate, which increased with temperature from 15 to 30°C for all instars, then declined again at higher temperatures. Survival was poor at 35°C for all instars, which suggests that this temperature is near or exceeds the Tmax. The mean time spent in each instar increased with each successive molt. The estimated Tmin based on the linear model also decreased as they progressed through the instars, however, this trend was not observed when the Tmin were estimated based on the Briere model. Likewise, the Tmax showed a decreasing trend as they progressed through the nymphal instars. At temperatures near both the Tmax and Tmin nymphs showed signs of stress; decreased survival, more incomplete molts, and more adults with partially expanded wings. The range of DD that were required for 10–90% of nymphs in an instar to complete development increased with instar and the extremes tended to come from individuals held at the temperatures closest to the thresholds.

The Tmax estimated for first instars is probably higher than the true Tmax since first instars placed at 40°C only survived for a few days. The complete mortality of first instars at 40°C makes sense as that temperature would not normally be reached during the spring when they first emerge. The estimated Tmin is likely accurate, but it is difficult to discern where the lower lethal threshold is, since the survival trend suggests that the first instars did persist at lower temperatures. Survival of hatchlings at low temperatures could be critical during cold snaps that may occur during hatch. Other insects like the gypsy moth often spend longer near the egg masses until temperatures rise above 10°C when they can disperse and begin feeding (McManus 1973, Keena and Shi 2019).

Previous MAXENT modeling for L. delicatula has used 11°C as the lower developmental threshold (Wakie et al. 2020). Another study set the lower developmental threshold to be 10°C and the upper developmental threshold to be 35°C calculating DD when development was followed in the field (Liu 2019). The Tmin reported here are similar to those previously used; however, it is important to note that these data showed that the Tmin varied for each instar. The Tmax from this study for second through fourth instars was similar to that previously used; however, under the conditions (temperature and humidity) assessed in this study the Tmax for fourth instars falls between 30 and 35°C as there was complete mortality at 35°C for fourth instars. Under different humilities or varying temperatures, the nymphs may be able to survive higher temperatures.

Mortality of nymphs that occurred during the beginning of each instar was likely due to temperature stress or variation in temperature sensitivity within the population, while later mortality may have been due to molting issues or resource depletion. Other factors may also have impacted L. delicatula survival rates including an infestation of eulophid mites on the A. altissima in the greenhouse during the last month of data collection. In addition, the plants in cages maintained their vigor better when watered from the top, which could not be done in the rearing tubes. Humidity differences between the temperatures may also have impacted observed mortality since at warmer temperatures moisture occasionally was evident on the inside of the containers. In most cases, however, the nymphs were able to move to more optimal humidity locations in the tubes but if they got trapped in the moisture they would die. Also, nymphs showed preferences for some plants over others so providing them with a choice within the cage may be a better option. This host plant choosiness of L. delicatula has been documented in the field and may be tied to nutrient differences between plants within a species (Mason et al. 2020).

It was interesting that temperature did not have a significant effect on adult weight or size (as measured by the hind tibia length). This may indicate that nymphs must reach a certain size before they can molt and so must compensate for temperature differences by extending the length of time in the instar at lower temperatures where the metabolism will be the slowest. Temperature, however, did influence wing size significantly in males and in females. The reduction in wing size at 15 and 30°C appeared to be due to issues in fully expanding the wings in both sexes at these temperatures which were close to the Tmin or Tmax for fourth instar nymphs. Previous research has shown that wing area does not have a significant effect on the flight capabilities of female L. delicatula adults (Wolfin et al. 2019). However, since this reduction in wing size was due to issue with fully expanding their wings, it would still affect flight capabilities.

For the second and third instars, there was a bi-modal distribution for the time in instar. It is possible that this is a difference between sexes, however, this could not be confirmed, as individual nymphs were not followed. Females spent significantly longer as fourth instars at 20, 25, and 30°C, which supports this hypothesis. Field observations also found that adult populations were skewed to males when the first adults start appearing (Baker et al 2019).

Previous research found that at 20°C, the duration for first, second, third, and fourth instars was 18.8, 20.9, 20.8, and 22.2 d, respectively on bittersweet (Park et al. 2009), which is considerably shorter than our study. This was especially true for third and fourth instars. This could be due to nutritional differences between hosts or potentially because the temperature in the previously study was assumed, not documented, to be 20°C. Also, in a preliminary trial using left over nymphs from this study, fourth instars at 25°C on V. labrusca only took an average of 23 d compared with the 38 d on A. altissima (unpublished data), so further work on the effects of host on developmental rates is merited.

It is important to note that L. delicatula takes longer to develop than other planthoppers. For example, Nilaparvata lugens (Stål), a multivoltine planthopper in the family Delphacidae (Hemiptera), was found to take an average of 5.6, 4.9, 5.1, 4.7 and 4.4 d to complete the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth instars at 20°C (Vattikuti et al. 2019). As L. delicatula only has one generation per year, it makes sense that it would take longer to develop than species that have multiple generations per year. The large size of L. delicatula likely contributes to this difference as well. This also suggests that there is a low risk of L. delicatula having multiple generations per year in any part of its range due to its relatively long development time and the fact that it overwinters as eggs.

Previous research determined the range of cumulative DD requirements for first, second, third, and fourth instars in Pennsylvania to be 153–652, 340–881, 567–1020, and 738–1227 DD10, respectively (Liu 2019). If the data from the current study were converted to Tmin of 10°C then the range of cumulative DD for each instar would approximately be (not exact since we did not follow individuals) 165–490, 315–1165, 525–1865, and 740–2525 DD10, for first, second, third, and fourth instars, respectively. The expanded DD ranges may be due to including temperatures near the upper and lower thresholds or to restricting nymphal feed to a single food source since there is some evidence that they may grow faster when they have access to multiple hosts.

This study suggests that L. delicatula experiences thermal stress when exposed to temperatures greater than 30°C but can develop slowly at temperatures as low as 15°C. This ability may help buffer the nymphs against the periods of low temperature that might be expected in the early spring when egg hatch begins. Based on these results, L. delicatula probably will not perform very well in extremely hot climates in the southern United States where temperature often go above 30°C. Research on the invasive Lymantria dispar (L.) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) has suggested that its poorer performance at temperatures greater than 28°C contributes to limiting its potential geographic range in North America (Thompson et al 2017). Further studies that look at its ability to withstand sudden cold snaps or heat waves are needed to get a better idea of its potential range.

The current study also provides data that can be useful in conjunction with the field data from Liu (2019) for developing a phenology model for L. delicatula, to aid in stage-specific prediction for management as individuals leave forests and invading nearby vineyards or other crops. The model will be further aided by incorporation of data on egg diapause to more accurately predict potential range for this insect in North America. These data may be useful for developing optimal laboratory rearing methods. Without an efficient laboratory rearing methodology for L. delicatula, mass rearing of discovered natural enemies needed for field-testing or release will be limited, especially outside the infested zone. Efforts to screen pesticides are equally restricted by the resources needed to obtain the large numbers of even aged individuals from natural populations. Year-round mass rearing would allow rapid screening of many pesticides and other monitoring or control methods.

Disclaimer: The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official endorsement or approval by the U.S. Department of Agriculture or the Forest Service of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Richards, C. Rodriguez-Saona, and R. T. Trotter for critically reviewing the manuscript and the anonymous reviewers for their input that improved the paper. We thank P. Moore, J. Richards, and N. Lowe for technical assistance. We also thank D. Mikus, T. Trotter, B. McMahon, X. Wu, I. Urquhart, M. Barr, L. Schmel, B. Walsh, and D. Long for help collecting the egg masses used in these studies. This work was funded in part by USDA APHIS PPQ S&T interagency agreement 10-8130-0840-IA (FS 19IA11242303103) with the Forest Service and AP19PPQS&T00C117 cooperative agreement with Rutgers University.

References Cited