-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Leticia Rodríguez-Alcolado, Elena Grueso-Navarro, Ángel Arias, Alfredo J Lucendo, Emilio J Laserna-Mendieta, Impact of HLA-DQA1*05 Genotype in Immunogenicity and Failure to Treatment with Tumour Necrosis Factor-alpha Antagonists in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis, Journal of Crohn's and Colitis, Volume 18, Issue 7, July 2024, Pages 1034–1052, https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjae006

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

HLA-DQA1*05 carriage has been associated with an increased risk of immunogenicity in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases treated with tumour necrosis factor-alpha [TNF-a] antagonists. Results have shown an inconsistent association with a loss of response [LOR] in patients with inflammatory bowel disease [IBD], which could be modified when using proactive optimisation and association with immunomodulatory drugs.

To define the association of HLA-DQA1*05 on anti-drug antibody development and loss of response [LOR] to anti-TNF-a in IBD.

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and SCOPUS, for the period up to August 2023, to identify studies reporting the risk of immunogenicity and/or LOR in IBD patients with HLA-DQA1*05 genotype.

A total of 24 studies comprising 12 papers, 11 abstracts and one research letter, with a total of 5727 IBD patients, were included. In a meta-analysis of 10 studies [2984 patients; 41.9% with HLA-DQA1*05 genotype], HLA-DQA1*05 carriers had higher risk of immunogenicity compared with non-carriers (risk ratio, 1.54; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.23 − 1.94; I2 = 62%) [low certainty evidence]. Lack of therapeutic drug monitoring [TDM] increased immunogenicity in the presence of risk human leukocyte antigen [HLA] [risk ratio 1.97; 95% CI, 1.35 − 2.88; I2 = 66%], whereas proactive TDM revoked this association [very low certainty of evidence]. A meta-analysis of six studies [765 patients] found that risk for secondary LOR was higher among HLA-DQA1*05 carriers [hazard ratio 2.21; 95% CI, 1.69 − 2.88; I2 = 0%] [very low certainty evidence], although definition and time to assessment varied widely among studies.

HLA-DQA1*05 carriage may be associated with an increased risk of immunogenicity and secondary LOR in IBD patients treated with TNF-a antagonists.

1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases [IBD], mainly comprising Crohn’s disease [CD] and ulcerative colitis [UC], are chronic inflammatory conditions that primarily affect the gastrointestinal tract. Since they may involve other organs, they are considered systemic diseases. With a steady increase in prevalence in developed and newly industrialised countries,1 IBD represents an important health problem: it affects patients of productive age; is associated with significant morbidity and disability2; and is costly due to long-term and often expensive treatments.3 In moderate and severe forms of the disease, treatment is usually based on immunosuppressant and/or biologic drugs aimed at reducing gut inflammation by attenuating the activity of the immune system.

Tumour necrosis factor-alpha [TNFα] antagonists were the first biologic agents used in IBD, and are currently the most widely used biologics for treating IBD patients, as well as being effective in other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases [IMIDs]. However, a proportion of patients do not respond to induction with anti-TNFα drugs [primary non-responders] and others can lose response during maintenance [secondary non-responders].4 The latter is predicted by low drug concentrations,5 mediated in part by the development of neutralising antidrug antibodies [ADAs], also referred to as immunogenicity.6 Combining immunomodulator [IMM] therapy was found to mitigate the risk of developing ADA.5 Immunogenicity to biologic therapies is a major concern, and the identification of patients at increased risk of immunogenicity to TNFα antagonist has been the subject of intense research in recent years. The implications for the choice of IBD treatment, the adoption of disease monitoring strategies, or the potential to ameliorate immunogenicity through combination with IMMs, has produced an abundant body of literature. This is particularly after the association of the human leukocyte antigen [HLA] allele group HLA-DQA1*05 with the development of ADA to TNFα antagonists.7 Carrying the HLA-DQA1*05 genotype has been associated with increased formation of ADA in patients treated with infliximab and adalimumab for IBD and other IMIDs.8 However, conflicting results have been provided on the effect of HLA-DQA1*05 and the risk for secondary loss of response [LOR],9,10 treatment persistence,11,12 and the effect of therapeutic drug monitoring,13,14 and these areas need to be analysed.

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the association between HLA-DQA1*05 carriage and the risk of immunogenicity to TNFα antagonists in patients with IBD. The effect of HLA-DQA1*05 on primary non-response [PNR], secondary LOR, treatment discontinuation [defined either as time to cessation, or proportion of patients who stopped treatment], and adverse events were also assessed, whenever possible. The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations [GRADE] framework was used to critically appraise certainty of evidence.15

2. Methods

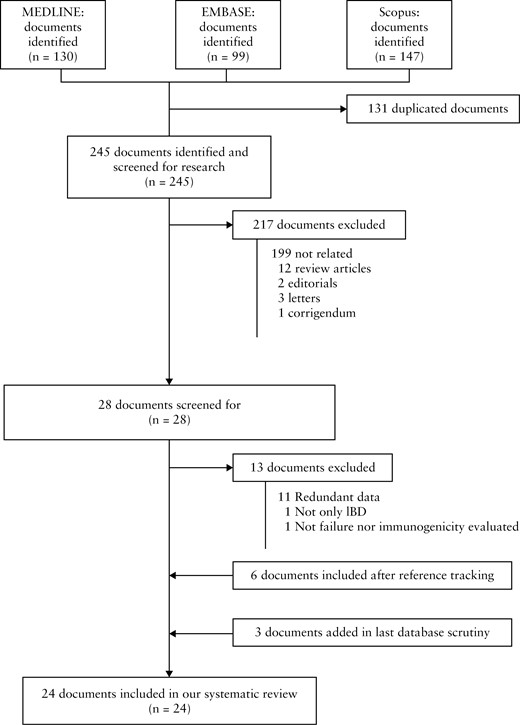

We used Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis [PRISMA] methodology for conducting this systematic review,16 registered in the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols [https://inplasy.com] as INPLASY202320076. No funding was received for the review.

2.1. Selection criteria

We included any study that met the following inclusion criteria: [1] patients: paediatric or adult patients with IBD who were treated with the anti-TNFα drugs infliximab, adalimumab, or golimumab; [2] exposure: carriage of at least one copy of HLA-DQA1*05; [3] comparator: not carrying HLA-DQA1*05; [4] outcomes: development of ADA to anti-TNFα drugs, and failure [defined either as PNR, secondary LOR, treatment discontinuation, or adverse events] to anti-TNFα therapy.

Inclusion criteria incorporated observational studies [both retrospective and prospective designs] and randomised controlled trials with adult, paediatric, or mixed populations. Abstracts were included and no restrictions were placed on language of publication. Documents identified through the reading of the selected articles and communications were also included. We excluded review articles, systematic reviews, clinical guidelines, book chapters, letters to the editor, and editorials with no original data. Studies lacking information on the desired outcomes [immunogenicity, treatment failure, or both]; studies not carried out on humans; and those providing duplicated information [ie, abstracts repeatedly presented to different congresses, or abstracts that were subsequently published as a full paper] were also excluded.

2.2. Search strategy

A systematic literature search was performed in duplicate [by AA and AJL] in three databases [PubMed, EMBASE, and Scopus] for the period from database inception up to January 2023. The search terms were: ([Infliximab/therapeutic use] OR [Adalimumab/pharmacology/therapeutic use] OR [Tumour Necrosis Factor Inhibitors/therapeutic use] OR [Tumour Necrosis Factor-alpha/genetics/therapeutic use]; OR [adalimumab] OR [TNF inhibitor or anti-TNF]; OR [TNF inhibitors]; OR [TNF-alpha] OR [infliximab]); AND ([dqa1 05*] OR [HLA-DQ alpha-Chains/genetics] OR [HLA-DQA1*]; OR [HLA-DQ alpha-Chains]; OR [HLA-DQA1 antigen]).

The results of the full search were merged into a single list, where duplicate records were identified and removed. Two researchers [LRA, EGN] independently performed the screening of the unified list, reviewing the title and abstract of every publication, and excluding irrelevant studies. Where disagreement occurred, consensus was reached through discussion with a third researcher [EJLM]. In cases of non-English text articles, Google Translate was first used to determine eligibility, followed by a professional translation service if eligible; however, this was not needed.

Literature searches were repeated on August 29, 2023, to retrieve the most recent documents and provide updated results.

2.3. Data extraction

Full text and supplementary data of the selected articles were retrieved and studied by two researchers [LRA, EGN], who independently extracted relevant information using a standardised data extraction form, followed by a cross-check of the results. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third researcher [EJLM]. The extracted data included: the last name of first author, publication year, country of origin, type of publication, time of follow-up, study design, number of patients, age and sex [% males] of patients, type of IBD included, outcomes measured and their definitions, therapeutic drug monitoring [TDM] strategy [if any], type of anti-TNFα used and line of treatment [first- or second-line], HLA or single nucleotide polymorphism [SNP] determination and by which method, use of concomitant IMMs, prevalence of HLADQA1*05 carriage, and rate of failure to treatment and immunogenicity according to HLADQA1*05 carriage.

2.4. Risk of bias assessment

Retrieved documents were evaluated in duplicate [AJL and AA] for risk of bias using the Robins-E tool [Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies—of Exposure].17 A study was considered to be at low risk of bias if each of the bias items could be categorised as low-risk. However, studies were judged as having a high risk of bias if any of the items were deemed high-risk.

2.5. Outcomes assessed

Outcomes of interest included: a] the risk of immunogenicity [defined as ADA development according to method for assessment] in patients with HLA-DQA1*05 genotype; b] clinical impact of carrying HLA-DQA1*05 in anti-TNFα drug failure [defined either as PNR, LOR, treatment discontinuation, or development of adverse events]. Curiously, two studies reported results for failure and/or immunogenicity not for patients but calculated for events per each treatment.9,18

2.6. Synthesis methods

To summarise the findings of the review on the immunogenicity outcome, a meta-analysis was carried out, including the raw number of patients with ADA development according to HLA-DQA1*05 carriage. For two studies,7,19 these data could not be obtained directly from the paper so authors were contacted, but only one response was received.7

Heterogeneity between studies was assessed by means of a chi square test [Cochran Q statistic] and quantified with the I2 statistic. If p <0.05 and/or I2 >50%, there was significant heterogeneity and a random effects model was used. Generally, I2 was used to evaluate the level of heterogeneity, assigning the categories low, moderate, and high to I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75%, respectively.20

For immunogenicity outcomes, a random effects meta-analysis was performed. Results were expressed as pooled Mantel-Haenszel risk ratios [RRs] with 95% confidence interval [95% CI] and forest plot graph. A sensitivity analysis by excluding studies with high risk of bias was performed. Publication bias was evaluated with the aid of a funnel plot, the asymmetry of which was assessed through Egger tests.21

For secondary endpoints, descriptive summaries and data tables were created for anti-TNFα drug failure, to address the high variability of definitions and outcomes used [Supplementary Table S1]. When summary data were not available for each intervention group, an overall estimate of the effect of each study was obtained, after extraction of hazard ratios data and meta-analyses using the generic inverse variance method.

All calculations were made with StatsDirect statistical software version 2.7.9 [StatsDirect, Cheshire, UK] and Review Manager [Cochrane Collaboration].

2.7. Subgroup analysis

For testing how sensitive our results were to changes in the study methods or data used in the review, subgroup analyses were planned according to type of publication [full paper or abstract], type of disease [CD or UC], anti-TNFα agent used [infliximab or adalimumab], patients’ age [adult or paediatric series], type of assay for ADA measurement [tolerant or sensitive], TDM [proactive or no TDM mentioned], and risk of bias in source documents.

2.8. Certainty of evidence

We ascertained certainty of evidence for the primary outcomes using the GRADE approach.15 This specifies certainty for a body of evidence for each outcome as high, moderate, low, and very low, by considering five domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias.22

3. Results

3.1. Results of the systematic literature search

The search retrieved 245 non-duplicated documents. After screening titles and abstracts, 28 studies were reviewed in detail with full reading, and 13 discarded. Six additional studies were identified by reference tracking, and three more added from the final database search. Thus 24 studies, reporting on 23 individual patient cohorts, were finally included in the systematic review [Figure 1].

3.2. Main characteristics of the included studies

The main data extracted from the selected studies are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. Table 1 details data on study design, patient demographics, IBD type, and treatment details [anti-TNFα drug with or without concomitant IMMs]; Table 2 focuses on outcome assessed, determination techniques and prevalence of HLA-DQA1*05, method for measurement of ADA, line of anti-TNFα treatment, and main conclusions of each individual study.

Main characteristics of the included studies re: type of study, patient demographics, type of inflammatory bowel disease, and type of treatment.

| First author, year . | Country . | Type of publication . | Follow-up in months, median [IQR] . | Cohort design . | No. of patients . | Type of IBD . | Age of patients in years, median [IQR] . | Population of study . | Male [%] . | Type of anti-TNFα drug . | Concomitant use of IMM . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aleman Gonzalez, 202223 | UK | Abstract | 12 | Prospective | 76 | CD [56.6%] UC [42.1%] IBD-U [1.3%] | No info | No info | No info | No info | 44.0% |

| Angulo McGrath, 202112 | Spain | Abstract | 35 [58] | Retrospective | 88 | CD [71.6%] UC [28.4%] | 39.0 [20.0] | No info | 52.3% | IFX | Yes, but no data |

| Bangma, 202024 | The Netherlands | Full paper | No info | Prospective | 376 | CD [73.9%] UC [22.6%] IBD-U [3.5%] | 47.0 [21.0] | No info | 34.6% | IFX [75.5%] ADL [24.5%] | 47.3% |

| Colman, 202113,25 | USA | Full paper nd abstract | 12 | Prospective | 78 [51 with HLA data] | CD | 12.0 [10.0-15.0] | Mixed [paediatric dominance] | 64.7%a | IFX | 3.9%a |

| Davis Gonzalez, 20229 | Spain | Full paper | 108–156b | Retrospective | 150 | CD [72.0%] UC [28.0%] | No info | Adults | 60.7% | IFX [42.9%] ADL [35.9%] Other [21.2%]c | CD: 35.2% UC: 43.0% |

| Doherty, 202326 | Ireland | Abstract | 65.8 | Retrospective | 877 | CD [69.9%] UC [30.1%] | No info | No info | 48.6% | IFX [34.3%] ADL [62.4%] Golimumab [0.3%] | 22.5% |

| Fuentes Valenzuela, 202327 | Spain | Full paper | 17 [8–31] | Retrospective | 112 | CD [80.4%] UC [19.3%] | HLA-DQA1*05-: 40.3 [25.3–49.7] HLA-DQA1*05+: 37.6 [25.3–47.1] | Mixed | 58.0% | IFX ADL | 35.7% |

| Gonzalez, 202128 | UK | Abstract | 15 [9–29] | Retrospective | 94 | UC | No info | No info | No info | IFX | 52.2% |

| Gu, 202218 | USA | Abstract | 11 [1–204] | Retrospective | 129 | CD [83.7%] UC [14.7%] IBD-U [1.6%] | No info | No info | No info | IFX ADL | 29.9% |

| Guardiola, 201929 | Spain | Abstract | 56d | Retrospective | 64 | CD [80.4%] UC [31.2%] | No info | No info | No info | IFX | No info |

| Guardiola Capon, 202010 | Spain | Abstract | 51 [35–74] | Retrospective | 53 | CD | No info | No info | No info | ADL | Yes, but no data |

| Hu, 202119 | China | Full paper | 20 [13–30] | Retrospective | 62 [58 with HLA data] | CD | 12.4 [10.0-14.35] | Pediatric | 62.9% | IFX | 14.5% |

| Ioannou, 202130 | USA | Abstract | No info | Retrospective | 610 | CD [64.9%] UC [32.8%] IBD-U [2.3%] | HLA-DQA1*05-: 39.0 [17.0-83.0] HLA-DQA1*05+: 40.0 [22.0-82.0] | Adults | 52.6% | IFX [55,7%] ADL [26,9%] Other [17.4%]c | No info |

| Laserna Mendieta, 202311 | Spain | Full paper | 116 [96–145] | Prospective | 131 | CD | 36.4 [27.7-46] | Adults | 50.4% | IFX | 51.9% |

| Lopez Blanco, 202231 | Spain | Abstract | No info | Retrospective | 208 | IBD | No info | No info | No info | IFX ADL | No info |

| Pascual Oliver, 202332 | Spain | Full paper | 24 [11–66] | Retrospective | 199 | CD [80.9%] UC [19.1%] | 41.8 ± 15.5d | No info | 50.8% | IFX [60.8%] ADL [36.2%] Golimumab [3%] | 59.8% |

| Salvador Martin, 202333 | Spain | Full paper | 108 | Ambispective | 340 | CD [70.5%] UC [27.4%] IBD-U [2.1%] | 12.2 [4.1] | Paediatric | 60.3% | IFX [67.1%] ADL [32.9%] | 87.6% |

| Sazonovs, 20207 | UK | Full paper | 36 | Prospective | 1240 | CD | IFX: 31.3e [21.2–46.0] ADL: 37.6e [28.7–50.3] | Mixed | 47.3% | IFX [59.8%] ADL [40.2%] | IFX: 60.4% ADL: 50.6% |

| Shimoda, 202334 | Japan | Full paper | No info | Retrospective | 189 | CD | No info | No info | 71.4% | IFX | 16.4% |

| Spencer, 202214 | USA | Research letter | 12 | Prospective | 186 | CD [70.4%] UC [27.4%] IBD-U [2.2%] | 17.0 [14.0–20.0] | Mixed | 52.2% | IFX | 9.7% |

| Suris Marin, 202135 | Spain | Abstract | >6 | Retrospective | 99 | CD [65.7%] UC [34.3%] | No info | No info | No info | IFX | Yes, but no data |

| Wilson, 201936 | Canada | Full paper | 36 [22–55] | Retrospective | 262 | CD [58.0%] UC [42.0%] | 39.7d [18.0–79.0] | Adults | 48.1% | IFX | 90.5% |

| Zhu, 202337 | China | Full paper | 10 [5–17] | No info | 104 | CD | 30.0 [24.0–37.0] | Adults | 73.1% | IFX | No |

| First author, year . | Country . | Type of publication . | Follow-up in months, median [IQR] . | Cohort design . | No. of patients . | Type of IBD . | Age of patients in years, median [IQR] . | Population of study . | Male [%] . | Type of anti-TNFα drug . | Concomitant use of IMM . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aleman Gonzalez, 202223 | UK | Abstract | 12 | Prospective | 76 | CD [56.6%] UC [42.1%] IBD-U [1.3%] | No info | No info | No info | No info | 44.0% |

| Angulo McGrath, 202112 | Spain | Abstract | 35 [58] | Retrospective | 88 | CD [71.6%] UC [28.4%] | 39.0 [20.0] | No info | 52.3% | IFX | Yes, but no data |

| Bangma, 202024 | The Netherlands | Full paper | No info | Prospective | 376 | CD [73.9%] UC [22.6%] IBD-U [3.5%] | 47.0 [21.0] | No info | 34.6% | IFX [75.5%] ADL [24.5%] | 47.3% |

| Colman, 202113,25 | USA | Full paper nd abstract | 12 | Prospective | 78 [51 with HLA data] | CD | 12.0 [10.0-15.0] | Mixed [paediatric dominance] | 64.7%a | IFX | 3.9%a |

| Davis Gonzalez, 20229 | Spain | Full paper | 108–156b | Retrospective | 150 | CD [72.0%] UC [28.0%] | No info | Adults | 60.7% | IFX [42.9%] ADL [35.9%] Other [21.2%]c | CD: 35.2% UC: 43.0% |

| Doherty, 202326 | Ireland | Abstract | 65.8 | Retrospective | 877 | CD [69.9%] UC [30.1%] | No info | No info | 48.6% | IFX [34.3%] ADL [62.4%] Golimumab [0.3%] | 22.5% |

| Fuentes Valenzuela, 202327 | Spain | Full paper | 17 [8–31] | Retrospective | 112 | CD [80.4%] UC [19.3%] | HLA-DQA1*05-: 40.3 [25.3–49.7] HLA-DQA1*05+: 37.6 [25.3–47.1] | Mixed | 58.0% | IFX ADL | 35.7% |

| Gonzalez, 202128 | UK | Abstract | 15 [9–29] | Retrospective | 94 | UC | No info | No info | No info | IFX | 52.2% |

| Gu, 202218 | USA | Abstract | 11 [1–204] | Retrospective | 129 | CD [83.7%] UC [14.7%] IBD-U [1.6%] | No info | No info | No info | IFX ADL | 29.9% |

| Guardiola, 201929 | Spain | Abstract | 56d | Retrospective | 64 | CD [80.4%] UC [31.2%] | No info | No info | No info | IFX | No info |

| Guardiola Capon, 202010 | Spain | Abstract | 51 [35–74] | Retrospective | 53 | CD | No info | No info | No info | ADL | Yes, but no data |

| Hu, 202119 | China | Full paper | 20 [13–30] | Retrospective | 62 [58 with HLA data] | CD | 12.4 [10.0-14.35] | Pediatric | 62.9% | IFX | 14.5% |

| Ioannou, 202130 | USA | Abstract | No info | Retrospective | 610 | CD [64.9%] UC [32.8%] IBD-U [2.3%] | HLA-DQA1*05-: 39.0 [17.0-83.0] HLA-DQA1*05+: 40.0 [22.0-82.0] | Adults | 52.6% | IFX [55,7%] ADL [26,9%] Other [17.4%]c | No info |

| Laserna Mendieta, 202311 | Spain | Full paper | 116 [96–145] | Prospective | 131 | CD | 36.4 [27.7-46] | Adults | 50.4% | IFX | 51.9% |

| Lopez Blanco, 202231 | Spain | Abstract | No info | Retrospective | 208 | IBD | No info | No info | No info | IFX ADL | No info |

| Pascual Oliver, 202332 | Spain | Full paper | 24 [11–66] | Retrospective | 199 | CD [80.9%] UC [19.1%] | 41.8 ± 15.5d | No info | 50.8% | IFX [60.8%] ADL [36.2%] Golimumab [3%] | 59.8% |

| Salvador Martin, 202333 | Spain | Full paper | 108 | Ambispective | 340 | CD [70.5%] UC [27.4%] IBD-U [2.1%] | 12.2 [4.1] | Paediatric | 60.3% | IFX [67.1%] ADL [32.9%] | 87.6% |

| Sazonovs, 20207 | UK | Full paper | 36 | Prospective | 1240 | CD | IFX: 31.3e [21.2–46.0] ADL: 37.6e [28.7–50.3] | Mixed | 47.3% | IFX [59.8%] ADL [40.2%] | IFX: 60.4% ADL: 50.6% |

| Shimoda, 202334 | Japan | Full paper | No info | Retrospective | 189 | CD | No info | No info | 71.4% | IFX | 16.4% |

| Spencer, 202214 | USA | Research letter | 12 | Prospective | 186 | CD [70.4%] UC [27.4%] IBD-U [2.2%] | 17.0 [14.0–20.0] | Mixed | 52.2% | IFX | 9.7% |

| Suris Marin, 202135 | Spain | Abstract | >6 | Retrospective | 99 | CD [65.7%] UC [34.3%] | No info | No info | No info | IFX | Yes, but no data |

| Wilson, 201936 | Canada | Full paper | 36 [22–55] | Retrospective | 262 | CD [58.0%] UC [42.0%] | 39.7d [18.0–79.0] | Adults | 48.1% | IFX | 90.5% |

| Zhu, 202337 | China | Full paper | 10 [5–17] | No info | 104 | CD | 30.0 [24.0–37.0] | Adults | 73.1% | IFX | No |

ADL, adalimumab; CD, Crohn’s disease; HLA, human leukocyte antigens; HLA-DQA1*05-, non-carrier of HLA-DQA1*05; HLA-DQA1*05+, carrier of HLA-DQA1*05; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IFX, infliximab; IMID, immune-mediated inflammatory disease; IMM, immunomodulatory drugs; IQR, interquartile range; no info, no information; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBD-U, inflammatory bowel disease unclassified.

aThe data correspond to the 51 patients with results for HLA.

bThe reported result is the range.

cOther treatments were vedolizumab and ustekinumab.

dThe reported result is the mean.

eNot reported if it is mean or median.

Main characteristics of the included studies re: type of study, patient demographics, type of inflammatory bowel disease, and type of treatment.

| First author, year . | Country . | Type of publication . | Follow-up in months, median [IQR] . | Cohort design . | No. of patients . | Type of IBD . | Age of patients in years, median [IQR] . | Population of study . | Male [%] . | Type of anti-TNFα drug . | Concomitant use of IMM . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aleman Gonzalez, 202223 | UK | Abstract | 12 | Prospective | 76 | CD [56.6%] UC [42.1%] IBD-U [1.3%] | No info | No info | No info | No info | 44.0% |

| Angulo McGrath, 202112 | Spain | Abstract | 35 [58] | Retrospective | 88 | CD [71.6%] UC [28.4%] | 39.0 [20.0] | No info | 52.3% | IFX | Yes, but no data |

| Bangma, 202024 | The Netherlands | Full paper | No info | Prospective | 376 | CD [73.9%] UC [22.6%] IBD-U [3.5%] | 47.0 [21.0] | No info | 34.6% | IFX [75.5%] ADL [24.5%] | 47.3% |

| Colman, 202113,25 | USA | Full paper nd abstract | 12 | Prospective | 78 [51 with HLA data] | CD | 12.0 [10.0-15.0] | Mixed [paediatric dominance] | 64.7%a | IFX | 3.9%a |

| Davis Gonzalez, 20229 | Spain | Full paper | 108–156b | Retrospective | 150 | CD [72.0%] UC [28.0%] | No info | Adults | 60.7% | IFX [42.9%] ADL [35.9%] Other [21.2%]c | CD: 35.2% UC: 43.0% |

| Doherty, 202326 | Ireland | Abstract | 65.8 | Retrospective | 877 | CD [69.9%] UC [30.1%] | No info | No info | 48.6% | IFX [34.3%] ADL [62.4%] Golimumab [0.3%] | 22.5% |

| Fuentes Valenzuela, 202327 | Spain | Full paper | 17 [8–31] | Retrospective | 112 | CD [80.4%] UC [19.3%] | HLA-DQA1*05-: 40.3 [25.3–49.7] HLA-DQA1*05+: 37.6 [25.3–47.1] | Mixed | 58.0% | IFX ADL | 35.7% |

| Gonzalez, 202128 | UK | Abstract | 15 [9–29] | Retrospective | 94 | UC | No info | No info | No info | IFX | 52.2% |

| Gu, 202218 | USA | Abstract | 11 [1–204] | Retrospective | 129 | CD [83.7%] UC [14.7%] IBD-U [1.6%] | No info | No info | No info | IFX ADL | 29.9% |

| Guardiola, 201929 | Spain | Abstract | 56d | Retrospective | 64 | CD [80.4%] UC [31.2%] | No info | No info | No info | IFX | No info |

| Guardiola Capon, 202010 | Spain | Abstract | 51 [35–74] | Retrospective | 53 | CD | No info | No info | No info | ADL | Yes, but no data |

| Hu, 202119 | China | Full paper | 20 [13–30] | Retrospective | 62 [58 with HLA data] | CD | 12.4 [10.0-14.35] | Pediatric | 62.9% | IFX | 14.5% |

| Ioannou, 202130 | USA | Abstract | No info | Retrospective | 610 | CD [64.9%] UC [32.8%] IBD-U [2.3%] | HLA-DQA1*05-: 39.0 [17.0-83.0] HLA-DQA1*05+: 40.0 [22.0-82.0] | Adults | 52.6% | IFX [55,7%] ADL [26,9%] Other [17.4%]c | No info |

| Laserna Mendieta, 202311 | Spain | Full paper | 116 [96–145] | Prospective | 131 | CD | 36.4 [27.7-46] | Adults | 50.4% | IFX | 51.9% |

| Lopez Blanco, 202231 | Spain | Abstract | No info | Retrospective | 208 | IBD | No info | No info | No info | IFX ADL | No info |

| Pascual Oliver, 202332 | Spain | Full paper | 24 [11–66] | Retrospective | 199 | CD [80.9%] UC [19.1%] | 41.8 ± 15.5d | No info | 50.8% | IFX [60.8%] ADL [36.2%] Golimumab [3%] | 59.8% |

| Salvador Martin, 202333 | Spain | Full paper | 108 | Ambispective | 340 | CD [70.5%] UC [27.4%] IBD-U [2.1%] | 12.2 [4.1] | Paediatric | 60.3% | IFX [67.1%] ADL [32.9%] | 87.6% |

| Sazonovs, 20207 | UK | Full paper | 36 | Prospective | 1240 | CD | IFX: 31.3e [21.2–46.0] ADL: 37.6e [28.7–50.3] | Mixed | 47.3% | IFX [59.8%] ADL [40.2%] | IFX: 60.4% ADL: 50.6% |

| Shimoda, 202334 | Japan | Full paper | No info | Retrospective | 189 | CD | No info | No info | 71.4% | IFX | 16.4% |

| Spencer, 202214 | USA | Research letter | 12 | Prospective | 186 | CD [70.4%] UC [27.4%] IBD-U [2.2%] | 17.0 [14.0–20.0] | Mixed | 52.2% | IFX | 9.7% |

| Suris Marin, 202135 | Spain | Abstract | >6 | Retrospective | 99 | CD [65.7%] UC [34.3%] | No info | No info | No info | IFX | Yes, but no data |

| Wilson, 201936 | Canada | Full paper | 36 [22–55] | Retrospective | 262 | CD [58.0%] UC [42.0%] | 39.7d [18.0–79.0] | Adults | 48.1% | IFX | 90.5% |

| Zhu, 202337 | China | Full paper | 10 [5–17] | No info | 104 | CD | 30.0 [24.0–37.0] | Adults | 73.1% | IFX | No |

| First author, year . | Country . | Type of publication . | Follow-up in months, median [IQR] . | Cohort design . | No. of patients . | Type of IBD . | Age of patients in years, median [IQR] . | Population of study . | Male [%] . | Type of anti-TNFα drug . | Concomitant use of IMM . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aleman Gonzalez, 202223 | UK | Abstract | 12 | Prospective | 76 | CD [56.6%] UC [42.1%] IBD-U [1.3%] | No info | No info | No info | No info | 44.0% |

| Angulo McGrath, 202112 | Spain | Abstract | 35 [58] | Retrospective | 88 | CD [71.6%] UC [28.4%] | 39.0 [20.0] | No info | 52.3% | IFX | Yes, but no data |

| Bangma, 202024 | The Netherlands | Full paper | No info | Prospective | 376 | CD [73.9%] UC [22.6%] IBD-U [3.5%] | 47.0 [21.0] | No info | 34.6% | IFX [75.5%] ADL [24.5%] | 47.3% |

| Colman, 202113,25 | USA | Full paper nd abstract | 12 | Prospective | 78 [51 with HLA data] | CD | 12.0 [10.0-15.0] | Mixed [paediatric dominance] | 64.7%a | IFX | 3.9%a |

| Davis Gonzalez, 20229 | Spain | Full paper | 108–156b | Retrospective | 150 | CD [72.0%] UC [28.0%] | No info | Adults | 60.7% | IFX [42.9%] ADL [35.9%] Other [21.2%]c | CD: 35.2% UC: 43.0% |

| Doherty, 202326 | Ireland | Abstract | 65.8 | Retrospective | 877 | CD [69.9%] UC [30.1%] | No info | No info | 48.6% | IFX [34.3%] ADL [62.4%] Golimumab [0.3%] | 22.5% |

| Fuentes Valenzuela, 202327 | Spain | Full paper | 17 [8–31] | Retrospective | 112 | CD [80.4%] UC [19.3%] | HLA-DQA1*05-: 40.3 [25.3–49.7] HLA-DQA1*05+: 37.6 [25.3–47.1] | Mixed | 58.0% | IFX ADL | 35.7% |

| Gonzalez, 202128 | UK | Abstract | 15 [9–29] | Retrospective | 94 | UC | No info | No info | No info | IFX | 52.2% |

| Gu, 202218 | USA | Abstract | 11 [1–204] | Retrospective | 129 | CD [83.7%] UC [14.7%] IBD-U [1.6%] | No info | No info | No info | IFX ADL | 29.9% |

| Guardiola, 201929 | Spain | Abstract | 56d | Retrospective | 64 | CD [80.4%] UC [31.2%] | No info | No info | No info | IFX | No info |

| Guardiola Capon, 202010 | Spain | Abstract | 51 [35–74] | Retrospective | 53 | CD | No info | No info | No info | ADL | Yes, but no data |

| Hu, 202119 | China | Full paper | 20 [13–30] | Retrospective | 62 [58 with HLA data] | CD | 12.4 [10.0-14.35] | Pediatric | 62.9% | IFX | 14.5% |

| Ioannou, 202130 | USA | Abstract | No info | Retrospective | 610 | CD [64.9%] UC [32.8%] IBD-U [2.3%] | HLA-DQA1*05-: 39.0 [17.0-83.0] HLA-DQA1*05+: 40.0 [22.0-82.0] | Adults | 52.6% | IFX [55,7%] ADL [26,9%] Other [17.4%]c | No info |

| Laserna Mendieta, 202311 | Spain | Full paper | 116 [96–145] | Prospective | 131 | CD | 36.4 [27.7-46] | Adults | 50.4% | IFX | 51.9% |

| Lopez Blanco, 202231 | Spain | Abstract | No info | Retrospective | 208 | IBD | No info | No info | No info | IFX ADL | No info |

| Pascual Oliver, 202332 | Spain | Full paper | 24 [11–66] | Retrospective | 199 | CD [80.9%] UC [19.1%] | 41.8 ± 15.5d | No info | 50.8% | IFX [60.8%] ADL [36.2%] Golimumab [3%] | 59.8% |

| Salvador Martin, 202333 | Spain | Full paper | 108 | Ambispective | 340 | CD [70.5%] UC [27.4%] IBD-U [2.1%] | 12.2 [4.1] | Paediatric | 60.3% | IFX [67.1%] ADL [32.9%] | 87.6% |

| Sazonovs, 20207 | UK | Full paper | 36 | Prospective | 1240 | CD | IFX: 31.3e [21.2–46.0] ADL: 37.6e [28.7–50.3] | Mixed | 47.3% | IFX [59.8%] ADL [40.2%] | IFX: 60.4% ADL: 50.6% |

| Shimoda, 202334 | Japan | Full paper | No info | Retrospective | 189 | CD | No info | No info | 71.4% | IFX | 16.4% |

| Spencer, 202214 | USA | Research letter | 12 | Prospective | 186 | CD [70.4%] UC [27.4%] IBD-U [2.2%] | 17.0 [14.0–20.0] | Mixed | 52.2% | IFX | 9.7% |

| Suris Marin, 202135 | Spain | Abstract | >6 | Retrospective | 99 | CD [65.7%] UC [34.3%] | No info | No info | No info | IFX | Yes, but no data |

| Wilson, 201936 | Canada | Full paper | 36 [22–55] | Retrospective | 262 | CD [58.0%] UC [42.0%] | 39.7d [18.0–79.0] | Adults | 48.1% | IFX | 90.5% |

| Zhu, 202337 | China | Full paper | 10 [5–17] | No info | 104 | CD | 30.0 [24.0–37.0] | Adults | 73.1% | IFX | No |

ADL, adalimumab; CD, Crohn’s disease; HLA, human leukocyte antigens; HLA-DQA1*05-, non-carrier of HLA-DQA1*05; HLA-DQA1*05+, carrier of HLA-DQA1*05; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IFX, infliximab; IMID, immune-mediated inflammatory disease; IMM, immunomodulatory drugs; IQR, interquartile range; no info, no information; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBD-U, inflammatory bowel disease unclassified.

aThe data correspond to the 51 patients with results for HLA.

bThe reported result is the range.

cOther treatments were vedolizumab and ustekinumab.

dThe reported result is the mean.

eNot reported if it is mean or median.

Main characteristics of the included studies: measured outcome, definitions of failure and immunogenicity to anti-TNFα treatment, determination and prevalence of HLA-DQA1*05, and relevant conclusions.

| First author, year . | Outcome . | Failure definition . | Measure of immunogenicity . | Therapeutic drug monitoring . | Line of treatment with anti-TNFα . | Determination of HLA . | Prevalence of HLA . | Main outcome for failure [HLA +/-] . | Immunogenicity outcome [HLA +/-] . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aleman Gonzalez, 202223 | Failure | TD | NA | No info | No info | No info | 46.7% | No difference according to HLA carriage p = 0.3 | NA |

| Angulo McGrath, 202112 | Failure | LOR | NA | No info | No info | No info | 42.0% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR Multivariate: HR = 2.32, 95% CI 1.07–5.02, p = 0.03 | NA |

| Bangma, 202024 | Immunogenicity | NA | Radio-immunoassay, Drug-tolerant Cut-off: ≥12 AU/mL | No info | No info | SNP WGS and genome-wide genotyping array | 39.6% | NA | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 27%, HLA–: 20% OR = 1.65, 95% CI 0.95–2.85, p = 0.075 |

| Colman, 202113,25 | Failure Immunogenicity | LOR | ECLIA, Drug tolerant Cut-off [ng/mL]: low [22–200], medium [201–1000], high [>1000] | Proactive | 1st line: 100% | PCR-SSO | 49.0% | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 24%, HLA–: 46%, p = 0.17 | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 60.0%, HLA –: 69.2%, p = 0.69 |

| Davis Gonzalez, 20229 | Failurea | PNR, LOR, TD, AE | NA | No info | First-line CD: 41.1%b First-line UC: 45.2%b | PCR-SSP | CD: 41.0% UC: 38.0% | No difference according to HLA carriage p >0.30 for the 4 outcomes assessed | NA |

| Doherty, 202326 | Failure | TD | NA | No info | 1st line: 100% | HLA imputation | 38.1% | HLA + had increased probability of shorter TD but only for homozygous carriers p = 0.007 | NA |

| Fuentes Valenzuela, 202327 | Failure | PNR, LOR, TD, AE | ΝΑ | Proactive | First-line: 92.9% Second-line: 7.1% | PCR-SSO | CD: 42.2% UC: 63.6% | HLA + had decreased probability of TD HLA+: 15.4%, HLA–: 38.3% HR = 0.31, 95% CI 0.12–0.81, p = 0.02 | NA |

| Gonzalez, 202128 | Failure Immunogenicity | TD | No info | No info | No info | No info | 39.1% | No difference according to HLA carriage HR = 2.36, 95% CI = 0.89–6.25, p = 0.06 | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation HLA+: 59%, HLA–: 24%, p = 0.002 HR = 4.54, 95% CI = 1.73–11.89 |

| Gu, 202218 | Failurea Immunogenicity | TD | No info | No info | No info | PCR-SSO | 42.9% | No difference according to HLA carriage p = 0.89 | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation HLA+: 27.0%, HLA–: 10.7%, p = 0.01 |

| Guardiola, 201929 | Failure | LOR | NA | No info | No info | No info | 31.0% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR Multivariate: HR = 3.5, 95% CI 1.6–7.5, p = 0.002 | NA |

| Guardiola Capon, 202010 | Failure | LOR | NA | No info | No info | No info | 45.0% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR Multivariate HR = 2.74, 95% CI 1.2–6.2, p = 0.02 | NA |

| Hu, 202119 | Immunogenicity | NA | Time to ADA detection by IC assay Cut-off ≥ 30 ng/mL | Reactive | First-line: 100% | SNP genotyping | No info | NA | No difference according to HLA carriage No statistical data provided |

| Ioannou, 202130 | Immunogenicity | NA | Cut-off: ≥ 10 AU/mL | No info | No info | SNP WGS | IFX: 41.9% ADL: 50.9% | NA | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation, but only for ADL IFX: HLA+: 32.2%, HLA–: 25.6%, p = 0.28 ADL: HLA+: 41.5%, HLA–: 15.7%, p = 0.004 |

| Laserna Mendieta, 202311 | Failure | TD | NA | Reactive | First-line: 90.8% Second-line: 9.2% | PCR-SSO & SNP genotyping | PCR-SSO: 40.5% SNP: 38.2% | No difference according to HLA carriage PCR-SSO: HLA+: 52.8%, HLA–: 47.4%, p = 0.544 SNP: HLA+: 52.0%, HLA–: 48.1%, p = 0.668 | NA |

| Lopez Blanco, 202231 | Immunogenicity | NA | ELISA Cut-off ≥ 10 AU/mL | No info | No info | PCR-SSO | 57.7% | NA | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 11.6%, HLA–: 10.2% |

| Pascual Oliver, 202332 | Failure | PNR, LOR, AE | NA | No [specified that proactive approach was not followed] | First-line: 100% | PCR-SSO | 42.4% | No difference according to HLA carriage p >0.30 for the three outcomes assessed | NA |

| Salvador Martín, 202333 | Failure | TD | NA | No info | First-line: 93.5% Second-line: 6.5% | SNP genotyping | CD: 45.8% UC: 40.8% IFX: 43.0% ADL: 48.2% | HLA + had increased probability of TD only for CD and ADL CD, Multivariate: HR = 2.07, 95% CI 1.07–3.99, p = 0.030 UC, Multivariate: HR = 1.40, 95% CI, 0.68–2.89, p = 0.358 IFX, Multivariate: HR = 1.44, 95% CI 0.79–2.62, p = 0.237 ADL, Multivariate: HR = 2.32, 95% CI 1.02–5.26, p = 0.044 | NA |

| Sazonovs, 20207 | Failure Immunogenicity | TD | ELISA, Drug tolerant cut-off: >10 AU/mL | Proactive | First-line: 100% | SNP genotyping/HLA imputation | 39.0% | HLA + had increased probability of TD only for ADL in monotherapy No statistical data provided | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation IFX: HR = 1.92, 95% CI, 1.57–2.33 ADL: HR = 1.89, 95% CI, 1.32–2.70 |

| Shimoda, 202334 | Failure | TD | NA | No info | First-line: 100% | SNP array genotyping | 19.6% | HLA + had increased probability of TD Multivariate: HR = 2.23, 95% CI 1.10–4.51, p = 0.026 | NA |

| Spencer, 202214 | Failure Immunogenicity | TD | Homogeneous mobility shift assay, Drug-tolerant Cut-off: ≥ 1.19 µg/mL | Proactive | First-line: 77.9% Second-line: 23.1% | SNP Risk immune test | 45.6% | No difference according to HLA carriage p = 0.58 | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 10.6%, HLA–: 13.8% HR = 0.7, 95% CI 0.2–2.0, p = 0.55 |

| Suris Marin, 202135 | Failure | LOR, TD | NA | No info | No info | No info | 39.4% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR Multivariate: HR = 1.90, 95% CI 1.14–3,31, p = 0.015 | NA |

| Wilson, 201936 | Failure Immunogenicity | LOR, TD, AE | ELISA, Drug-sensitive Cut-off: no info | No info | No info | SNP allelic discrimination | 40.1% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR and TD LOR: HR = 2.34, 95% CI 1.41–3.88, p = 0.001 TD: HR = 2.27, 95% CI 1.46–3.43, p = 2.5 × 10–4 | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation HLA+: 25.7%, HLA –: 4.5%, HR = 7.29, 95% CI 2.97–17.19, p = 1.5 × 10–5 |

| Zhu, 202337 | Immunogenicity | NA | ELISA, Drug-tolerant Cut-off: titres of 1:20 and ≥1.:60 were considered low- and high-titre, respectively. | Proactive | First-line: 94.2% Second-line: 5.8%c | SNP genotyping | 36.5% | NA | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation HLA+: 71.1%, HLA–: 43.9%, p = 0.01 OR = 2.94, 95% CI 1.19–7.3, p = 0.02 |

| First author, year . | Outcome . | Failure definition . | Measure of immunogenicity . | Therapeutic drug monitoring . | Line of treatment with anti-TNFα . | Determination of HLA . | Prevalence of HLA . | Main outcome for failure [HLA +/-] . | Immunogenicity outcome [HLA +/-] . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aleman Gonzalez, 202223 | Failure | TD | NA | No info | No info | No info | 46.7% | No difference according to HLA carriage p = 0.3 | NA |

| Angulo McGrath, 202112 | Failure | LOR | NA | No info | No info | No info | 42.0% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR Multivariate: HR = 2.32, 95% CI 1.07–5.02, p = 0.03 | NA |

| Bangma, 202024 | Immunogenicity | NA | Radio-immunoassay, Drug-tolerant Cut-off: ≥12 AU/mL | No info | No info | SNP WGS and genome-wide genotyping array | 39.6% | NA | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 27%, HLA–: 20% OR = 1.65, 95% CI 0.95–2.85, p = 0.075 |

| Colman, 202113,25 | Failure Immunogenicity | LOR | ECLIA, Drug tolerant Cut-off [ng/mL]: low [22–200], medium [201–1000], high [>1000] | Proactive | 1st line: 100% | PCR-SSO | 49.0% | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 24%, HLA–: 46%, p = 0.17 | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 60.0%, HLA –: 69.2%, p = 0.69 |

| Davis Gonzalez, 20229 | Failurea | PNR, LOR, TD, AE | NA | No info | First-line CD: 41.1%b First-line UC: 45.2%b | PCR-SSP | CD: 41.0% UC: 38.0% | No difference according to HLA carriage p >0.30 for the 4 outcomes assessed | NA |

| Doherty, 202326 | Failure | TD | NA | No info | 1st line: 100% | HLA imputation | 38.1% | HLA + had increased probability of shorter TD but only for homozygous carriers p = 0.007 | NA |

| Fuentes Valenzuela, 202327 | Failure | PNR, LOR, TD, AE | ΝΑ | Proactive | First-line: 92.9% Second-line: 7.1% | PCR-SSO | CD: 42.2% UC: 63.6% | HLA + had decreased probability of TD HLA+: 15.4%, HLA–: 38.3% HR = 0.31, 95% CI 0.12–0.81, p = 0.02 | NA |

| Gonzalez, 202128 | Failure Immunogenicity | TD | No info | No info | No info | No info | 39.1% | No difference according to HLA carriage HR = 2.36, 95% CI = 0.89–6.25, p = 0.06 | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation HLA+: 59%, HLA–: 24%, p = 0.002 HR = 4.54, 95% CI = 1.73–11.89 |

| Gu, 202218 | Failurea Immunogenicity | TD | No info | No info | No info | PCR-SSO | 42.9% | No difference according to HLA carriage p = 0.89 | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation HLA+: 27.0%, HLA–: 10.7%, p = 0.01 |

| Guardiola, 201929 | Failure | LOR | NA | No info | No info | No info | 31.0% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR Multivariate: HR = 3.5, 95% CI 1.6–7.5, p = 0.002 | NA |

| Guardiola Capon, 202010 | Failure | LOR | NA | No info | No info | No info | 45.0% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR Multivariate HR = 2.74, 95% CI 1.2–6.2, p = 0.02 | NA |

| Hu, 202119 | Immunogenicity | NA | Time to ADA detection by IC assay Cut-off ≥ 30 ng/mL | Reactive | First-line: 100% | SNP genotyping | No info | NA | No difference according to HLA carriage No statistical data provided |

| Ioannou, 202130 | Immunogenicity | NA | Cut-off: ≥ 10 AU/mL | No info | No info | SNP WGS | IFX: 41.9% ADL: 50.9% | NA | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation, but only for ADL IFX: HLA+: 32.2%, HLA–: 25.6%, p = 0.28 ADL: HLA+: 41.5%, HLA–: 15.7%, p = 0.004 |

| Laserna Mendieta, 202311 | Failure | TD | NA | Reactive | First-line: 90.8% Second-line: 9.2% | PCR-SSO & SNP genotyping | PCR-SSO: 40.5% SNP: 38.2% | No difference according to HLA carriage PCR-SSO: HLA+: 52.8%, HLA–: 47.4%, p = 0.544 SNP: HLA+: 52.0%, HLA–: 48.1%, p = 0.668 | NA |

| Lopez Blanco, 202231 | Immunogenicity | NA | ELISA Cut-off ≥ 10 AU/mL | No info | No info | PCR-SSO | 57.7% | NA | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 11.6%, HLA–: 10.2% |

| Pascual Oliver, 202332 | Failure | PNR, LOR, AE | NA | No [specified that proactive approach was not followed] | First-line: 100% | PCR-SSO | 42.4% | No difference according to HLA carriage p >0.30 for the three outcomes assessed | NA |

| Salvador Martín, 202333 | Failure | TD | NA | No info | First-line: 93.5% Second-line: 6.5% | SNP genotyping | CD: 45.8% UC: 40.8% IFX: 43.0% ADL: 48.2% | HLA + had increased probability of TD only for CD and ADL CD, Multivariate: HR = 2.07, 95% CI 1.07–3.99, p = 0.030 UC, Multivariate: HR = 1.40, 95% CI, 0.68–2.89, p = 0.358 IFX, Multivariate: HR = 1.44, 95% CI 0.79–2.62, p = 0.237 ADL, Multivariate: HR = 2.32, 95% CI 1.02–5.26, p = 0.044 | NA |

| Sazonovs, 20207 | Failure Immunogenicity | TD | ELISA, Drug tolerant cut-off: >10 AU/mL | Proactive | First-line: 100% | SNP genotyping/HLA imputation | 39.0% | HLA + had increased probability of TD only for ADL in monotherapy No statistical data provided | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation IFX: HR = 1.92, 95% CI, 1.57–2.33 ADL: HR = 1.89, 95% CI, 1.32–2.70 |

| Shimoda, 202334 | Failure | TD | NA | No info | First-line: 100% | SNP array genotyping | 19.6% | HLA + had increased probability of TD Multivariate: HR = 2.23, 95% CI 1.10–4.51, p = 0.026 | NA |

| Spencer, 202214 | Failure Immunogenicity | TD | Homogeneous mobility shift assay, Drug-tolerant Cut-off: ≥ 1.19 µg/mL | Proactive | First-line: 77.9% Second-line: 23.1% | SNP Risk immune test | 45.6% | No difference according to HLA carriage p = 0.58 | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 10.6%, HLA–: 13.8% HR = 0.7, 95% CI 0.2–2.0, p = 0.55 |

| Suris Marin, 202135 | Failure | LOR, TD | NA | No info | No info | No info | 39.4% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR Multivariate: HR = 1.90, 95% CI 1.14–3,31, p = 0.015 | NA |

| Wilson, 201936 | Failure Immunogenicity | LOR, TD, AE | ELISA, Drug-sensitive Cut-off: no info | No info | No info | SNP allelic discrimination | 40.1% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR and TD LOR: HR = 2.34, 95% CI 1.41–3.88, p = 0.001 TD: HR = 2.27, 95% CI 1.46–3.43, p = 2.5 × 10–4 | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation HLA+: 25.7%, HLA –: 4.5%, HR = 7.29, 95% CI 2.97–17.19, p = 1.5 × 10–5 |

| Zhu, 202337 | Immunogenicity | NA | ELISA, Drug-tolerant Cut-off: titres of 1:20 and ≥1.:60 were considered low- and high-titre, respectively. | Proactive | First-line: 94.2% Second-line: 5.8%c | SNP genotyping | 36.5% | NA | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation HLA+: 71.1%, HLA–: 43.9%, p = 0.01 OR = 2.94, 95% CI 1.19–7.3, p = 0.02 |

ADA, anti-drug antibodies; ADL, adalimumab; AE, adverse events; AU, arbitrary units; CD, Crohn’s disease; HLA, human leukocyte antigens; HLA-, non-carrier of HLA-DQA1*05; HLA+, carrier of HLA-DQA1*05; HR, hazard ratio; IC, immunochromatography; IFX, infliximab; OR, odds ratio; PCR-SSO, polymerase chain reaction-sequence specific oligonucleotide; PCR-SSP, polymerase chain reaction-sequence specific primer; PNR, primary non-response; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism, LOR, secondary loss of response; TD, treatment discontinuation; UC, ulcerative colitis; WGS, whole-genome sequencing; wPCDAI, weighted Paediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index.

aThe outcomes were measured for events per each treatment, and not for patients as in the remaining included studies.

bThe data correspond to number of biologic treatments.

cHad received IFX previously.

Main characteristics of the included studies: measured outcome, definitions of failure and immunogenicity to anti-TNFα treatment, determination and prevalence of HLA-DQA1*05, and relevant conclusions.

| First author, year . | Outcome . | Failure definition . | Measure of immunogenicity . | Therapeutic drug monitoring . | Line of treatment with anti-TNFα . | Determination of HLA . | Prevalence of HLA . | Main outcome for failure [HLA +/-] . | Immunogenicity outcome [HLA +/-] . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aleman Gonzalez, 202223 | Failure | TD | NA | No info | No info | No info | 46.7% | No difference according to HLA carriage p = 0.3 | NA |

| Angulo McGrath, 202112 | Failure | LOR | NA | No info | No info | No info | 42.0% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR Multivariate: HR = 2.32, 95% CI 1.07–5.02, p = 0.03 | NA |

| Bangma, 202024 | Immunogenicity | NA | Radio-immunoassay, Drug-tolerant Cut-off: ≥12 AU/mL | No info | No info | SNP WGS and genome-wide genotyping array | 39.6% | NA | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 27%, HLA–: 20% OR = 1.65, 95% CI 0.95–2.85, p = 0.075 |

| Colman, 202113,25 | Failure Immunogenicity | LOR | ECLIA, Drug tolerant Cut-off [ng/mL]: low [22–200], medium [201–1000], high [>1000] | Proactive | 1st line: 100% | PCR-SSO | 49.0% | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 24%, HLA–: 46%, p = 0.17 | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 60.0%, HLA –: 69.2%, p = 0.69 |

| Davis Gonzalez, 20229 | Failurea | PNR, LOR, TD, AE | NA | No info | First-line CD: 41.1%b First-line UC: 45.2%b | PCR-SSP | CD: 41.0% UC: 38.0% | No difference according to HLA carriage p >0.30 for the 4 outcomes assessed | NA |

| Doherty, 202326 | Failure | TD | NA | No info | 1st line: 100% | HLA imputation | 38.1% | HLA + had increased probability of shorter TD but only for homozygous carriers p = 0.007 | NA |

| Fuentes Valenzuela, 202327 | Failure | PNR, LOR, TD, AE | ΝΑ | Proactive | First-line: 92.9% Second-line: 7.1% | PCR-SSO | CD: 42.2% UC: 63.6% | HLA + had decreased probability of TD HLA+: 15.4%, HLA–: 38.3% HR = 0.31, 95% CI 0.12–0.81, p = 0.02 | NA |

| Gonzalez, 202128 | Failure Immunogenicity | TD | No info | No info | No info | No info | 39.1% | No difference according to HLA carriage HR = 2.36, 95% CI = 0.89–6.25, p = 0.06 | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation HLA+: 59%, HLA–: 24%, p = 0.002 HR = 4.54, 95% CI = 1.73–11.89 |

| Gu, 202218 | Failurea Immunogenicity | TD | No info | No info | No info | PCR-SSO | 42.9% | No difference according to HLA carriage p = 0.89 | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation HLA+: 27.0%, HLA–: 10.7%, p = 0.01 |

| Guardiola, 201929 | Failure | LOR | NA | No info | No info | No info | 31.0% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR Multivariate: HR = 3.5, 95% CI 1.6–7.5, p = 0.002 | NA |

| Guardiola Capon, 202010 | Failure | LOR | NA | No info | No info | No info | 45.0% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR Multivariate HR = 2.74, 95% CI 1.2–6.2, p = 0.02 | NA |

| Hu, 202119 | Immunogenicity | NA | Time to ADA detection by IC assay Cut-off ≥ 30 ng/mL | Reactive | First-line: 100% | SNP genotyping | No info | NA | No difference according to HLA carriage No statistical data provided |

| Ioannou, 202130 | Immunogenicity | NA | Cut-off: ≥ 10 AU/mL | No info | No info | SNP WGS | IFX: 41.9% ADL: 50.9% | NA | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation, but only for ADL IFX: HLA+: 32.2%, HLA–: 25.6%, p = 0.28 ADL: HLA+: 41.5%, HLA–: 15.7%, p = 0.004 |

| Laserna Mendieta, 202311 | Failure | TD | NA | Reactive | First-line: 90.8% Second-line: 9.2% | PCR-SSO & SNP genotyping | PCR-SSO: 40.5% SNP: 38.2% | No difference according to HLA carriage PCR-SSO: HLA+: 52.8%, HLA–: 47.4%, p = 0.544 SNP: HLA+: 52.0%, HLA–: 48.1%, p = 0.668 | NA |

| Lopez Blanco, 202231 | Immunogenicity | NA | ELISA Cut-off ≥ 10 AU/mL | No info | No info | PCR-SSO | 57.7% | NA | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 11.6%, HLA–: 10.2% |

| Pascual Oliver, 202332 | Failure | PNR, LOR, AE | NA | No [specified that proactive approach was not followed] | First-line: 100% | PCR-SSO | 42.4% | No difference according to HLA carriage p >0.30 for the three outcomes assessed | NA |

| Salvador Martín, 202333 | Failure | TD | NA | No info | First-line: 93.5% Second-line: 6.5% | SNP genotyping | CD: 45.8% UC: 40.8% IFX: 43.0% ADL: 48.2% | HLA + had increased probability of TD only for CD and ADL CD, Multivariate: HR = 2.07, 95% CI 1.07–3.99, p = 0.030 UC, Multivariate: HR = 1.40, 95% CI, 0.68–2.89, p = 0.358 IFX, Multivariate: HR = 1.44, 95% CI 0.79–2.62, p = 0.237 ADL, Multivariate: HR = 2.32, 95% CI 1.02–5.26, p = 0.044 | NA |

| Sazonovs, 20207 | Failure Immunogenicity | TD | ELISA, Drug tolerant cut-off: >10 AU/mL | Proactive | First-line: 100% | SNP genotyping/HLA imputation | 39.0% | HLA + had increased probability of TD only for ADL in monotherapy No statistical data provided | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation IFX: HR = 1.92, 95% CI, 1.57–2.33 ADL: HR = 1.89, 95% CI, 1.32–2.70 |

| Shimoda, 202334 | Failure | TD | NA | No info | First-line: 100% | SNP array genotyping | 19.6% | HLA + had increased probability of TD Multivariate: HR = 2.23, 95% CI 1.10–4.51, p = 0.026 | NA |

| Spencer, 202214 | Failure Immunogenicity | TD | Homogeneous mobility shift assay, Drug-tolerant Cut-off: ≥ 1.19 µg/mL | Proactive | First-line: 77.9% Second-line: 23.1% | SNP Risk immune test | 45.6% | No difference according to HLA carriage p = 0.58 | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 10.6%, HLA–: 13.8% HR = 0.7, 95% CI 0.2–2.0, p = 0.55 |

| Suris Marin, 202135 | Failure | LOR, TD | NA | No info | No info | No info | 39.4% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR Multivariate: HR = 1.90, 95% CI 1.14–3,31, p = 0.015 | NA |

| Wilson, 201936 | Failure Immunogenicity | LOR, TD, AE | ELISA, Drug-sensitive Cut-off: no info | No info | No info | SNP allelic discrimination | 40.1% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR and TD LOR: HR = 2.34, 95% CI 1.41–3.88, p = 0.001 TD: HR = 2.27, 95% CI 1.46–3.43, p = 2.5 × 10–4 | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation HLA+: 25.7%, HLA –: 4.5%, HR = 7.29, 95% CI 2.97–17.19, p = 1.5 × 10–5 |

| Zhu, 202337 | Immunogenicity | NA | ELISA, Drug-tolerant Cut-off: titres of 1:20 and ≥1.:60 were considered low- and high-titre, respectively. | Proactive | First-line: 94.2% Second-line: 5.8%c | SNP genotyping | 36.5% | NA | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation HLA+: 71.1%, HLA–: 43.9%, p = 0.01 OR = 2.94, 95% CI 1.19–7.3, p = 0.02 |

| First author, year . | Outcome . | Failure definition . | Measure of immunogenicity . | Therapeutic drug monitoring . | Line of treatment with anti-TNFα . | Determination of HLA . | Prevalence of HLA . | Main outcome for failure [HLA +/-] . | Immunogenicity outcome [HLA +/-] . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aleman Gonzalez, 202223 | Failure | TD | NA | No info | No info | No info | 46.7% | No difference according to HLA carriage p = 0.3 | NA |

| Angulo McGrath, 202112 | Failure | LOR | NA | No info | No info | No info | 42.0% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR Multivariate: HR = 2.32, 95% CI 1.07–5.02, p = 0.03 | NA |

| Bangma, 202024 | Immunogenicity | NA | Radio-immunoassay, Drug-tolerant Cut-off: ≥12 AU/mL | No info | No info | SNP WGS and genome-wide genotyping array | 39.6% | NA | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 27%, HLA–: 20% OR = 1.65, 95% CI 0.95–2.85, p = 0.075 |

| Colman, 202113,25 | Failure Immunogenicity | LOR | ECLIA, Drug tolerant Cut-off [ng/mL]: low [22–200], medium [201–1000], high [>1000] | Proactive | 1st line: 100% | PCR-SSO | 49.0% | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 24%, HLA–: 46%, p = 0.17 | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 60.0%, HLA –: 69.2%, p = 0.69 |

| Davis Gonzalez, 20229 | Failurea | PNR, LOR, TD, AE | NA | No info | First-line CD: 41.1%b First-line UC: 45.2%b | PCR-SSP | CD: 41.0% UC: 38.0% | No difference according to HLA carriage p >0.30 for the 4 outcomes assessed | NA |

| Doherty, 202326 | Failure | TD | NA | No info | 1st line: 100% | HLA imputation | 38.1% | HLA + had increased probability of shorter TD but only for homozygous carriers p = 0.007 | NA |

| Fuentes Valenzuela, 202327 | Failure | PNR, LOR, TD, AE | ΝΑ | Proactive | First-line: 92.9% Second-line: 7.1% | PCR-SSO | CD: 42.2% UC: 63.6% | HLA + had decreased probability of TD HLA+: 15.4%, HLA–: 38.3% HR = 0.31, 95% CI 0.12–0.81, p = 0.02 | NA |

| Gonzalez, 202128 | Failure Immunogenicity | TD | No info | No info | No info | No info | 39.1% | No difference according to HLA carriage HR = 2.36, 95% CI = 0.89–6.25, p = 0.06 | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation HLA+: 59%, HLA–: 24%, p = 0.002 HR = 4.54, 95% CI = 1.73–11.89 |

| Gu, 202218 | Failurea Immunogenicity | TD | No info | No info | No info | PCR-SSO | 42.9% | No difference according to HLA carriage p = 0.89 | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation HLA+: 27.0%, HLA–: 10.7%, p = 0.01 |

| Guardiola, 201929 | Failure | LOR | NA | No info | No info | No info | 31.0% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR Multivariate: HR = 3.5, 95% CI 1.6–7.5, p = 0.002 | NA |

| Guardiola Capon, 202010 | Failure | LOR | NA | No info | No info | No info | 45.0% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR Multivariate HR = 2.74, 95% CI 1.2–6.2, p = 0.02 | NA |

| Hu, 202119 | Immunogenicity | NA | Time to ADA detection by IC assay Cut-off ≥ 30 ng/mL | Reactive | First-line: 100% | SNP genotyping | No info | NA | No difference according to HLA carriage No statistical data provided |

| Ioannou, 202130 | Immunogenicity | NA | Cut-off: ≥ 10 AU/mL | No info | No info | SNP WGS | IFX: 41.9% ADL: 50.9% | NA | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation, but only for ADL IFX: HLA+: 32.2%, HLA–: 25.6%, p = 0.28 ADL: HLA+: 41.5%, HLA–: 15.7%, p = 0.004 |

| Laserna Mendieta, 202311 | Failure | TD | NA | Reactive | First-line: 90.8% Second-line: 9.2% | PCR-SSO & SNP genotyping | PCR-SSO: 40.5% SNP: 38.2% | No difference according to HLA carriage PCR-SSO: HLA+: 52.8%, HLA–: 47.4%, p = 0.544 SNP: HLA+: 52.0%, HLA–: 48.1%, p = 0.668 | NA |

| Lopez Blanco, 202231 | Immunogenicity | NA | ELISA Cut-off ≥ 10 AU/mL | No info | No info | PCR-SSO | 57.7% | NA | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 11.6%, HLA–: 10.2% |

| Pascual Oliver, 202332 | Failure | PNR, LOR, AE | NA | No [specified that proactive approach was not followed] | First-line: 100% | PCR-SSO | 42.4% | No difference according to HLA carriage p >0.30 for the three outcomes assessed | NA |

| Salvador Martín, 202333 | Failure | TD | NA | No info | First-line: 93.5% Second-line: 6.5% | SNP genotyping | CD: 45.8% UC: 40.8% IFX: 43.0% ADL: 48.2% | HLA + had increased probability of TD only for CD and ADL CD, Multivariate: HR = 2.07, 95% CI 1.07–3.99, p = 0.030 UC, Multivariate: HR = 1.40, 95% CI, 0.68–2.89, p = 0.358 IFX, Multivariate: HR = 1.44, 95% CI 0.79–2.62, p = 0.237 ADL, Multivariate: HR = 2.32, 95% CI 1.02–5.26, p = 0.044 | NA |

| Sazonovs, 20207 | Failure Immunogenicity | TD | ELISA, Drug tolerant cut-off: >10 AU/mL | Proactive | First-line: 100% | SNP genotyping/HLA imputation | 39.0% | HLA + had increased probability of TD only for ADL in monotherapy No statistical data provided | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation IFX: HR = 1.92, 95% CI, 1.57–2.33 ADL: HR = 1.89, 95% CI, 1.32–2.70 |

| Shimoda, 202334 | Failure | TD | NA | No info | First-line: 100% | SNP array genotyping | 19.6% | HLA + had increased probability of TD Multivariate: HR = 2.23, 95% CI 1.10–4.51, p = 0.026 | NA |

| Spencer, 202214 | Failure Immunogenicity | TD | Homogeneous mobility shift assay, Drug-tolerant Cut-off: ≥ 1.19 µg/mL | Proactive | First-line: 77.9% Second-line: 23.1% | SNP Risk immune test | 45.6% | No difference according to HLA carriage p = 0.58 | No difference according to HLA carriage HLA+: 10.6%, HLA–: 13.8% HR = 0.7, 95% CI 0.2–2.0, p = 0.55 |

| Suris Marin, 202135 | Failure | LOR, TD | NA | No info | No info | No info | 39.4% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR Multivariate: HR = 1.90, 95% CI 1.14–3,31, p = 0.015 | NA |

| Wilson, 201936 | Failure Immunogenicity | LOR, TD, AE | ELISA, Drug-sensitive Cut-off: no info | No info | No info | SNP allelic discrimination | 40.1% | HLA + had increased probability of LOR and TD LOR: HR = 2.34, 95% CI 1.41–3.88, p = 0.001 TD: HR = 2.27, 95% CI 1.46–3.43, p = 2.5 × 10–4 | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation HLA+: 25.7%, HLA –: 4.5%, HR = 7.29, 95% CI 2.97–17.19, p = 1.5 × 10–5 |

| Zhu, 202337 | Immunogenicity | NA | ELISA, Drug-tolerant Cut-off: titres of 1:20 and ≥1.:60 were considered low- and high-titre, respectively. | Proactive | First-line: 94.2% Second-line: 5.8%c | SNP genotyping | 36.5% | NA | HLA + had increased probability of ADA formation HLA+: 71.1%, HLA–: 43.9%, p = 0.01 OR = 2.94, 95% CI 1.19–7.3, p = 0.02 |

ADA, anti-drug antibodies; ADL, adalimumab; AE, adverse events; AU, arbitrary units; CD, Crohn’s disease; HLA, human leukocyte antigens; HLA-, non-carrier of HLA-DQA1*05; HLA+, carrier of HLA-DQA1*05; HR, hazard ratio; IC, immunochromatography; IFX, infliximab; OR, odds ratio; PCR-SSO, polymerase chain reaction-sequence specific oligonucleotide; PCR-SSP, polymerase chain reaction-sequence specific primer; PNR, primary non-response; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism, LOR, secondary loss of response; TD, treatment discontinuation; UC, ulcerative colitis; WGS, whole-genome sequencing; wPCDAI, weighted Paediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index.

aThe outcomes were measured for events per each treatment, and not for patients as in the remaining included studies.

bThe data correspond to number of biologic treatments.

cHad received IFX previously.

Of the 24 studies, 12 were full research papers,7,9,11,13,19,24,27,32–34,36,37 11 abstracts,10,12,18,23,25,26,28–31,35 and one a research letter.14 The same cohort of patients was used in the two studies by Colman et al. [the full paper did not include data previously reported in an abstract].13,25 Most cohorts reported on mixed IBD populations; seven cohorts included CD patients7,10,11,19,25,34,37 and one UC patients,28 exclusively. One cohort did not differentiate IBD variants.29 Overall, patients with CD predominated in mixed cohorts.

As for study design, 15 were retrospective cohorts, six were prospective, and data in one study were derived from a randomised controlled trial. The remaining study had no information on study design. Most of the studies [13 cohorts] included adult or mixed patients, with two studies reporting results in paediatric populations predominantly. Eight studies did not provide information about their targeted population. Fifteen cohorts were recruited in European countries, five were American cohorts, two came from China, and one from Japan. Follow-up length to outcome assessment varied greatly among cohorts, from a median of 10 months to 13 years.

Overall, the 23 patient cohorts provided data from 5727 individual patients with IBD [including 4349 with CD, 1129 with UC, 41 with IBD-unclassified, and 208 in whom IBD type was not specified]. Data on HLA-DQA1*05 were provided in all but 31 patients with IBD.

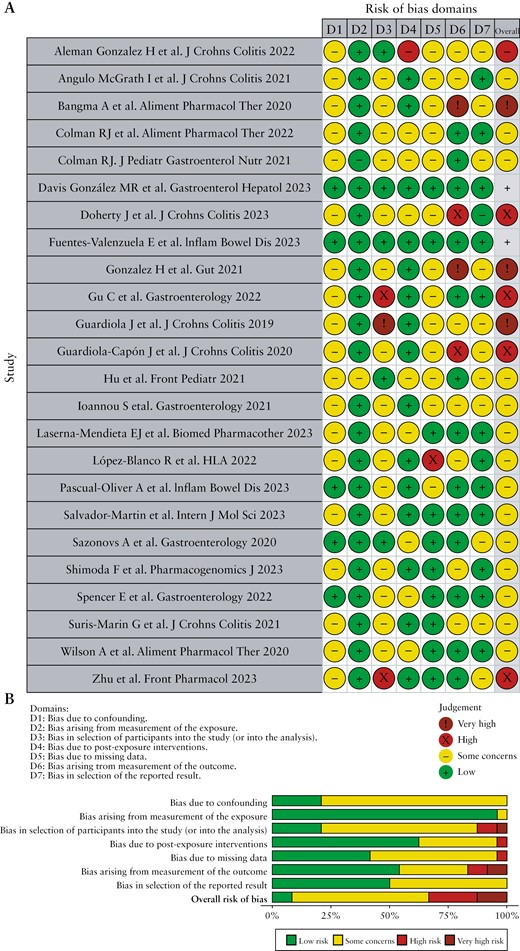

The overall risk of bias evaluated for the 24 individual studies revealed that eight presented a high or very high risk, 14 had an intermediate risk of bias [because concerns on some item were raised], and only two studies were judged as low risk of bias [Figure 2A]. The poor control of potential confounding factors in IBD patients which were not measured, the selection of participants onto the study, and the selection of the reported results were the main domains for risk of bias [Figure 2B].

Risk of bias of studies included in the systematic review according to the Cochrane ROBINS-E tool. A, ‘Traffic light’ plots of the domain-level judgments for each individual result. B, Weighted bar plots of the distribution of risk of bias judgements within each bias domain.

3.3. Type of TNFα antagonist and concomitant therapy

Among anti-TNFα drugs, infliximab and adalimumab were preferred, with infliximab being the most preferred. Only two cohorts used golimumab, in 33 patients overall.26,32 Specifically, 12 cohorts used exclusively infliximab,11,12,14,19,25,28,29,34–38 and adalimumab was only used exclusively in one cohort.10 Nine cohorts included patients treated with both infliximab and adalimumab.7,9,18,24,26,27,30–32 Details on the drug used were not provided in a further study.23 Despite two cohorts also including 138 patients treated with vedolizumab and ustekinumab,9,30 only results for patients treated with infliximab and adalimumab were reported and included in this systematic review.

The use of IMM drugs varied widely among individual studies, from 4%25 to 91%.36 The percentage of patients under concomitant immunosuppressant therapy was not reported in six cohorts10,12,29–31,35 and no patients were under combined therapy in the remaining study.37

3.4. Determination of HLA and frequency of HLA-DQA1*05 carriage

HLA-DQA1*05 genotyping was mostly undertaken by analysing the rs2097432 single nucleotide polymorphism [SNP] using different methods [direct genotyping or SNP arrays] in nine cohorts,7,14,19,24,30,33,34,36,37 and more complex methods based on polymerase chain reaction, either by sequence specific oligonucleotide [PCR-SSO] or by sequence specific priming [PCR-SSP], were used in five18,25,27,31,32 and one cohort,9 respectively. One study used both methods,11 another study used HLA imputation from whole genome sequencing,26 with no details being provided by the remaining [all abstract] six studies.

The frequency of HLA-DQA1*05 carriage was relatively homogeneous among patient cohorts, with most studies reporting 35–50% [range 20–64%].

3.5. Risk of immunogenicity to anti-TNFα drugs

Among the 11 patient cohorts (3027 patients; prevalence of HLA-DQA1*05, 41.9% [range, 37%–58%]) where this outcome was assessed, an association between HLA-DQA1*05 carriage and ADA formation was found in five studies7,18,28,36,37 [1829 patients] and 5 more [879 patients] found no association.13,14,19,24,25,31 One of the studies identified that HLA-DQA1*05 was associated with immunogenicity for adalimumab exclusively, but not for infliximab.30

The definition of immunogenicity was highly dependent on the method/assay and cut-off point used, and this was greatly variable among studies, with some providing incomplete or no information about the procedure for ADA determination [Supplementary Table S2]. At least five different methodologies were employed [electrochemiluminescence immunoassay or ECLIA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or ELISA, radioimmunoassay, homogeneous mobility shift assay, and immunochromatography], and several papers included incomplete descriptions of the assay19,30,31,36 [missed information about cut-off point, drug-tolerant or -sensitive type] or provided no information at all.18,28

To evaluate the effect of HLA-DQA1*05 carriage on immunogenicity, a meta-analysis was performed using raw data from source studies [Figure 3A]. One study that did not support association between HLA-DQA1*05 and immunogenicity was not included in the meta-analysis as the required data were neither found in the paper nor provided by the authors.19 Thus, 10 studies were included in the final analysis, with three caveats: only data from patients treated with infliximab and adalimumab were retrieved from the abstract by Ioannou et al.,30 data in the study by Gu et al. referred to events per treatment [instead per patient],18 and the data received from Sazonovs included 1237 of the 1240 patients reported in the initial cohort, in whom the HLA status was determined.7 Overall results showed that the presence of HLA-DQA1*05 genotype was associated with a 54% higher risk of immunogenicity, compared with non-carriers, in patients with IBD treated with TNFα antagonists (risk ratio [RR], 1.54; 95% confidence interval, 1.23–1.94) and with considerable heterogeneity [I2 = 67%]. Regarding subgroup analyses, the significant association between HLA-DQA1*05 carriage and immunogenicity was maintained in studies that included only adult patients and were published both as full articles and as abstracts, and in those that determined ADAs using drug tolerant assays. Exposure to both infliximab and adalimumab was significantly associated with ADA formation among HLA-DQA1*05 carriers when both drugs were evaluated separately [Table 3]. No meta-analyses were done for patients with UC, paediatric patients, or for drug-sensitive assays, as only one study per each subgroup was found.

Subgroup analyses comparing risk of immunogenicity [anti-drug antibodies formation] with anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha drugs according to HLA-DQA1*05 carriage.

| Subgroup analysis . | Number of cohorts . | Risk ratio [95% confidence interval] . | I2 . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient population | ||||

| Adult patients only | 3 | 2.17 [1.22 − 3.85] | 80% | 0.008 |

| Crohn’s disease patients only | 3 | 1.31 [0.98 − 1.74] | 67% | 0.06 |

| Type of TNFα antagonist | ||||

| Infliximab exclusively | 7 | 1.50 [1.10 − 2.05] | 77% | 0.01 |

| Adalimumab exclusively | 2 | 1.85 [1.18 − 2.90] | 39% | 0.008 |

| Publication type | ||||

| Abstracts | 4 | 1.81 [1.33 − 2.47] | 23% | <0.001 |

| Full papers | 6 | 1.42 [1.04 − 1.94] | 76% | 0.03 |

| Type of drug measurement assay | ||||

| Drug-tolerant assays | 5 | 1.28 [1.04 − 1.59] | 51% | 0.02 |

| Excluding high-risk bias studies | ||||

| Low/intermediate risk of bias | 6 | 1.41 [0.98 − 2.01] | 76% | 0.06 |

| Therapeutic drug monitoring | ||||

| Proactive | 4 | 1.24 [0.93 − 1.64] | 64% | 0.15 |

| No TDM strategy mentioned | 6 | 1.97 [1.35 − 2.88] | 66% | <0.001 |

| Subgroup analysis . | Number of cohorts . | Risk ratio [95% confidence interval] . | I2 . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient population | ||||

| Adult patients only | 3 | 2.17 [1.22 − 3.85] | 80% | 0.008 |

| Crohn’s disease patients only | 3 | 1.31 [0.98 − 1.74] | 67% | 0.06 |

| Type of TNFα antagonist | ||||

| Infliximab exclusively | 7 | 1.50 [1.10 − 2.05] | 77% | 0.01 |

| Adalimumab exclusively | 2 | 1.85 [1.18 − 2.90] | 39% | 0.008 |

| Publication type | ||||

| Abstracts | 4 | 1.81 [1.33 − 2.47] | 23% | <0.001 |

| Full papers | 6 | 1.42 [1.04 − 1.94] | 76% | 0.03 |

| Type of drug measurement assay | ||||

| Drug-tolerant assays | 5 | 1.28 [1.04 − 1.59] | 51% | 0.02 |

| Excluding high-risk bias studies | ||||

| Low/intermediate risk of bias | 6 | 1.41 [0.98 − 2.01] | 76% | 0.06 |

| Therapeutic drug monitoring | ||||

| Proactive | 4 | 1.24 [0.93 − 1.64] | 64% | 0.15 |

| No TDM strategy mentioned | 6 | 1.97 [1.35 − 2.88] | 66% | <0.001 |

TDM, therapeutic drug monitoring; I2, statistical inconsistency.

Subgroup analyses comparing risk of immunogenicity [anti-drug antibodies formation] with anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha drugs according to HLA-DQA1*05 carriage.

| Subgroup analysis . | Number of cohorts . | Risk ratio [95% confidence interval] . | I2 . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient population | ||||

| Adult patients only | 3 | 2.17 [1.22 − 3.85] | 80% | 0.008 |

| Crohn’s disease patients only | 3 | 1.31 [0.98 − 1.74] | 67% | 0.06 |

| Type of TNFα antagonist | ||||

| Infliximab exclusively | 7 | 1.50 [1.10 − 2.05] | 77% | 0.01 |

| Adalimumab exclusively | 2 | 1.85 [1.18 − 2.90] | 39% | 0.008 |

| Publication type | ||||

| Abstracts | 4 | 1.81 [1.33 − 2.47] | 23% | <0.001 |

| Full papers | 6 | 1.42 [1.04 − 1.94] | 76% | 0.03 |

| Type of drug measurement assay | ||||

| Drug-tolerant assays | 5 | 1.28 [1.04 − 1.59] | 51% | 0.02 |

| Excluding high-risk bias studies | ||||

| Low/intermediate risk of bias | 6 | 1.41 [0.98 − 2.01] | 76% | 0.06 |

| Therapeutic drug monitoring | ||||

| Proactive | 4 | 1.24 [0.93 − 1.64] | 64% | 0.15 |

| No TDM strategy mentioned | 6 | 1.97 [1.35 − 2.88] | 66% | <0.001 |

| Subgroup analysis . | Number of cohorts . | Risk ratio [95% confidence interval] . | I2 . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient population | ||||

| Adult patients only | 3 | 2.17 [1.22 − 3.85] | 80% | 0.008 |

| Crohn’s disease patients only | 3 | 1.31 [0.98 − 1.74] | 67% | 0.06 |

| Type of TNFα antagonist | ||||

| Infliximab exclusively | 7 | 1.50 [1.10 − 2.05] | 77% | 0.01 |

| Adalimumab exclusively | 2 | 1.85 [1.18 − 2.90] | 39% | 0.008 |

| Publication type | ||||

| Abstracts | 4 | 1.81 [1.33 − 2.47] | 23% | <0.001 |

| Full papers | 6 | 1.42 [1.04 − 1.94] | 76% | 0.03 |

| Type of drug measurement assay | ||||

| Drug-tolerant assays | 5 | 1.28 [1.04 − 1.59] | 51% | 0.02 |

| Excluding high-risk bias studies | ||||

| Low/intermediate risk of bias | 6 | 1.41 [0.98 − 2.01] | 76% | 0.06 |

| Therapeutic drug monitoring | ||||

| Proactive | 4 | 1.24 [0.93 − 1.64] | 64% | 0.15 |

| No TDM strategy mentioned | 6 | 1.97 [1.35 − 2.88] | 66% | <0.001 |

TDM, therapeutic drug monitoring; I2, statistical inconsistency.

![A, Forest plot comparing the risk of immunogenicity to TNFα antagonists [defined as positive serum anti-drug antibodies] in IBD patient carriers of HLA-DQA1*05 versus non-carriers. B, Begg funnel plot of studies risk of immunogenicity to TNFα antagonists in IBD patients with HLA DQA1*05. TNF, tumour necrosis factor; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ecco-jcc/18/7/10.1093_ecco-jcc_jjae006/1/m_jjae006_fig3.jpeg?Expires=1750213827&Signature=Lg7RTR9r0lcUXuK0ox2Lb1TqW-DsyVLVLvalst3QNT~Kgei7FtZQak21LBXNjMW05FNILMccS7A8hjSc4CH4tH-eiBr7YgVokMjdc8NyDhllJTt2xqdBqPcbLPwJFpZKiMwIANZaHv~H53vfsmv5q1QDqm02SMa4IuSBYiMIkmUjLtNLwnHrqj6DwL7r1SQ4qCTUrBxjCqjJQX8MMvkKr1DcgxXBGNKHekti-LFeXln3Y-8JrVZgQStj7maUT7w1KOF7Y6YrOH3~fDJQLH2jqY~00UzBOxwo1QCkAOt6tfASZ5v3bYbPKlpRzG3FN7Q2R6Ab4BIWrMxYlniKM-R5UQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

A, Forest plot comparing the risk of immunogenicity to TNFα antagonists [defined as positive serum anti-drug antibodies] in IBD patient carriers of HLA-DQA1*05 versus non-carriers. B, Begg funnel plot of studies risk of immunogenicity to TNFα antagonists in IBD patients with HLA DQA1*05. TNF, tumour necrosis factor; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Sensitivity analyses, excluding studies with a high risk of bias, maintained an association between HLA-DQA1*05 and ADA formation [n = 6 studies], but without statistical significance [p = 0.06].

No significant publication bias was found in the funnel plot analysis [Figure 3B] and Egger bias test [p = 0.52]. GRADE assessment found a low certainty of evidence for the impact of HLA DQA1*05 carriage on development of ADA to TNFα antagonists [Table 4].

Grade ASSESSMENT for HLA-DQA1*05 carriage compared with HLA-DQA1*05 non carriage for immunogenicity and effectiveness of TNFα antagonists in patients with IBD.

| Certainty assessment . | No. of patients . | Effect . | Certainty . | Importance . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies . | Study design . | Risk of bias . | Inconsistency . | Indirectness . | Imprecision . | Other considerations . | HLA-DQA1*05 carriage . | Anti-TNFα monotherapy . | Relative [95% CI] . | Absolute [95% CI] . | ||

| In IBD patients treated with anti-TNFα, does carrying HLA-DQA1*05 compared with not carrying HLA-DQA1*05 increase the risk of immunogenicity? [assessed with: anti-drug antibodies] . | ||||||||||||

| 10 | Observational studies | Seriousa | Seriousb | Not serious | Seriousc | All plausible residual confounding factors would reduce the demonstrated effect | 476/1250 [38.1%] | 461/1734 [26.6%] | RR 1.55 [1.23–1.95] | 146 more per 1000 [from 61 more to 253 more] | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | IMPORTANT |

| Certainty assessment . | No. of patients . | Effect . | Certainty . | Importance . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies . | Study design . | Risk of bias . | Inconsistency . | Indirectness . | Imprecision . | Other considerations . | HLA-DQA1*05 carriage . | Anti-TNFα monotherapy . | Relative [95% CI] . | Absolute [95% CI] . | ||

| In IBD patients treated with anti-TNFα, does carrying HLA-DQA1*05 compared with not carrying HLA-DQA1*05 increase the risk of immunogenicity? [assessed with: anti-drug antibodies] . | ||||||||||||

| 10 | Observational studies | Seriousa | Seriousb | Not serious | Seriousc | All plausible residual confounding factors would reduce the demonstrated effect | 476/1250 [38.1%] | 461/1734 [26.6%] | RR 1.55 [1.23–1.95] | 146 more per 1000 [from 61 more to 253 more] | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | IMPORTANT |

| In IBD patients treated with anti-TNFα, does carrying HLA-DQA1*05 compared with not carrying HLA-DQA1*05 increase the risk of secondary loss of response to treatment? [assessed with: clinical variables] . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not seriousd | Seriouse | Extremely seriousf | All plausible residual confounding factors would reduce the demonstrated effect | 178/440 [40.5%] | Not pooled | HR 2.21 [1.69–2.68] | See comment | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low | CRITICAL |

| In IBD patients treated with anti-TNFα, does carrying HLA-DQA1*05 compared with not carrying HLA-DQA1*05 increase the risk of secondary loss of response to treatment? [assessed with: clinical variables] . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not seriousd | Seriouse | Extremely seriousf | All plausible residual confounding factors would reduce the demonstrated effect | 178/440 [40.5%] | Not pooled | HR 2.21 [1.69–2.68] | See comment | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low | CRITICAL |

| Certainty assessment . | No. of patients carrying HLA-DQA1*05 gentotype . | Effect . | Certainty . | Importance . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies . | Study design . | Risk of bias . | Inconsistency . | Indirectness . | Imprecision . | Other considerations . | Anti-TNFα and IMM combination therapy . | Anti-TNFα monotherapy . | Relative [95% CI] . | Absolute [95% CI] . | ||

| In IBD patients carrying HLA-DQA1*05 and treated with anti-TNFα drugs, does associating immunomodulatory drugs [>70% of patients with combination therapy in patient cohorts] compared with monotherapy [<30% patients in anti-TNF-alpha monotherapy] reduce the risk of immunogenicity? [assessed with: antidrug antibodies] . | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousg | Not serious | Publication bias strongly suspected All plausible residual confounding factors would suggest spurious effect, whereas no effect was observedh | 27/105 [25.7%] | 24/110 [21.8%] | RR 1.18 [0.73–1.91] | See comment | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low | IMPORTANT |

| Certainty assessment . | No. of patients carrying HLA-DQA1*05 gentotype . | Effect . | Certainty . | Importance . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies . | Study design . | Risk of bias . | Inconsistency . | Indirectness . | Imprecision . | Other considerations . | Anti-TNFα and IMM combination therapy . | Anti-TNFα monotherapy . | Relative [95% CI] . | Absolute [95% CI] . | ||

| In IBD patients carrying HLA-DQA1*05 and treated with anti-TNFα drugs, does associating immunomodulatory drugs [>70% of patients with combination therapy in patient cohorts] compared with monotherapy [<30% patients in anti-TNF-alpha monotherapy] reduce the risk of immunogenicity? [assessed with: antidrug antibodies] . | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousg | Not serious | Publication bias strongly suspected All plausible residual confounding factors would suggest spurious effect, whereas no effect was observedh | 27/105 [25.7%] | 24/110 [21.8%] | RR 1.18 [0.73–1.91] | See comment | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low | IMPORTANT |

| In IBD patients carrying HLA-DQA1*05 and treated with anti-TNFα drugs, does associating immunomodulatory drugs [>70% of patients with combination therapy in patient cohorts] compared with monotherapy [<30% patients in anti-TNF-alpha monotherapy] reduce the risk of treatment failure? [assessed with: clinical criteria]? . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Very seriousi | Very seriousj | All plausible residual confounding factors would reduce the demonstrated effect | 50/105 [47.6%] | 11/110 [10%] | RR 4.76 [2.63–8.64] | See comment | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low | CRITICAL |