-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Misha Kabir, Siwan Thomas-Gibson, Ahmir Ahmad, Rawen Kader, Lulia Al-Hillawi, Joshua Mcguire, Lewis David, Krishna Shah, Rohit Rao, Roser Vega, James E East, Omar D Faiz, Ailsa L Hart, Ana Wilson, Cancer Biology or Ineffective Surveillance? A Multicentre Retrospective Analysis of Colitis-Associated Post-Colonoscopy Colorectal Cancers, Journal of Crohn's and Colitis, Volume 18, Issue 5, May 2024, Pages 686–694, https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjad189

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] is associated with high rates of post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer [PCCRC], but further in-depth qualitative analyses are required to determine whether they result from inadequate surveillance or aggressive IBD cancer evolution.

All IBD patients who had a colorectal cancer [CRC] diagnosed between January 2015 and July 2019 and a recent [<4 years] surveillance colonoscopy at one of four English hospital trusts underwent root cause analyses as recommended by the World Endoscopy Organisation to identify plausible PCCRC causative factors.

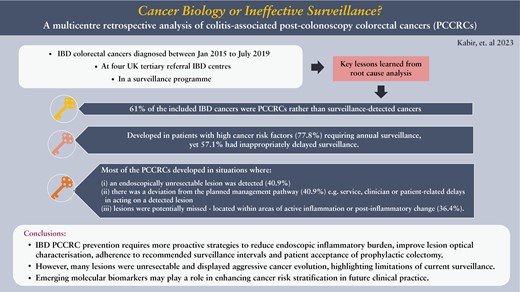

In total, 61% [n = 22/36] of the included IBD CRCs were PCCRCs. They developed in patients with high cancer risk factors [77.8%; n = 28/36] requiring annual surveillance, yet 57.1% [n = 20/35] had inappropriately delayed surveillance. Most PCCRCs developed in situations where [i] an endoscopically unresectable lesion was detected [40.9%; n = 9/22], [ii] there was a deviation from the planned management pathway [40.9%; n = 9/22], such as service-, clinician- or patient-related delays in acting on a detected lesion, or [iii] lesions were potentially missed as they were typically located within areas of active inflammation or post-inflammatory change [36.4%; n = 8/22].

IBD PCCRC prevention will require more proactive strategies to reduce endoscopic inflammatory burden, and to improve lesion optical characterization, adherence to recommended surveillance intervals, and patient acceptance of prophylactic colectomy. However, the significant proportion appearing to originate from non-adenomatous-looking mucosa which fail to yield neoplasia on biopsy yet display aggressive cancer evolution highlights the limitations of current surveillance. Emerging molecular biomarkers may play a role in enhancing cancer risk stratification in future clinical practice.

1. Introduction

Individuals with long-standing ulcerative colitis [UC] and extensive Crohn’s disease colitis are at an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer [CRC]. Despite UC-associated CRCs being detected at an earlier tumour stage if patients engage with surveillance,1 CRC-related mortality adjusted to the tumour stage remains higher in UC patients compared to the general population.2 Evaluating the efficacy of an inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] surveillance programme requires investigation into why some patients develop CRCs despite surveillance.

A proposed quality assurance measure for an endoscopy unit’s performance is the ‘post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer’ [PCCRC] rate.3 PCCRC 3-year rates across English National Health Service [NHS] providers are significantly increased at 35.5% in IBD patients and have not fallen between 2005 and 2013,4 despite improvements in endoscopic technologies and the introduction of British Society of Gastroenterology [BSG] surveillance interval guidelines in this high-risk population in 2010.5 Population-based cohort studies rely on mainly administrative data rather than individual endoscopic and histological data. Therefore, potentially attributable factors such as missed lesions due to poor bowel preparation can only be evaluated at a local level. All endoscopy units should perform root cause analyses of PCCRC cases and instigate a feedback mechanism to change future practice.3,6 The World Endoscopy Organisation [WEO] consensus panel have recommended structured categorization of PCCRCs, identifying potentially avoidable causative factors.3

The aim of this study is to retrospectively evaluate the quality of surveillance undertaken in IBD patients who have developed CRCs despite surveillance at multiple UK tertiary referral IBD centres. By comparison with surveillance-detected CRCs we aim to identify and learn from the preventable factors that contribute to IBD PCCRCs. Are IBD PCCRCs missed because of poor-quality surveillance or is this a phenomenon of aggressive IBD cancer evolution biology?

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population selection

A retrospective multicentre cohort study was performed involving four English hospital trusts with tertiary referral IBD centres, all equipped with high-definition endoscopy imaging and chromoendoscopy. Dysplasia is routinely double reported by two expert gastrointestinal histopathologists in these centres. All adult patients with Crohn’s colitis or UC who had been diagnosed with a CRC between January 2015 and July 2019 were identified from hospital records using CRC diagnostic codes, endoscopy, and histopathology reporting systems. Only patients who had had at least one surveillance colonoscopy at the same centre as where their cancer was diagnosed were included to allow for comprehensive retrospective review of the quality of surveillance performed in the run up to the cancer diagnosis. Cases were excluded if they did not have a histologically confirmed diagnosis of IBD colitis, or the cancer was not an adenocarcinoma, was categorized as a new CRC [i.e. their last colonoscopy had been more than 4 years prior to their CRC diagnosis], was found on their first ever surveillance colonoscopy, or was found within the anal squamous mucosa or an ileoanal pouch. Patient records were reviewed to obtain demographic and clinical data. CRC staging was determined using the tumour, node, and metastasis [TNM] classification criteria.7 All historical endoscopy reports and images were reviewed to assess the quality of the last surveillance colonoscopy performed before the cancer was diagnosed. If a cancer was detected at the time of their last colonoscopy only the quality and findings of the previous surveillance colonoscopy was evaluated as the last ‘cancer-negative’ surveillance colonoscopy. The adequacy of surveillance interval timing was based on the BSG guidelines at the time.5,8 A colonoscopy was considered complete if there was clearly written and photo-documented intubation of the caecum [or anastomosis]. If there was inadequate bowel preparation, the interval to a repeat colonoscopy was not standardized across the centres but left to the discretion of the endoscopist. Endoscopists were categorized by whether they had a declared specialist expertise in chromoendoscopy [dye and virtual] surveillance and complex polypectomy [i.e. expertise in resecting polyps that are greater than 2 cm, are flat, and/or are in difficult positions] or not.

A CRC was defined as a PCCRC if the last colonoscopy that had not identified a cancer [i.e. the last cancer-negative colonoscopy] was performed between 6 and 48 months prior to a diagnosis of a colorectal adenocarcinoma. The WEO categorization algorithm3 was used to identify potentially avoidable attributable factors as described in Table 1. A CRC that was diagnosed within 6 months of a cancer-negative surveillance endoscopic examination was defined as a ‘surveillance-detected’ cancer on the presumption that the endoscopic findings led to either a repeated targeted examination or surgery at which time the cancer was diagnosed. The PCCRCs were also defined by the timing of their detection in relation to the recommended surveillance interval. An interval PCCRC was a cancer identified before the next recommended surveillance interval. A non-interval PCCRC was a cancer identified at [Type A] or after [Type B] the next recommended surveillance interval or where no subsequent interval was recommended [Type C]. PCCRC status and WEO categorization of all the cases were independently verified by endoscopists with specialist expertise in IBD surveillance and complex polypectomy at each centre.

World Endoscopy Organisation [WEO] categorization of potential causative factors for PCCRCs

| WEO categorization of causative factors . | Explanation of category . | N [%] . |

|---|---|---|

| [a] Probable incomplete resection of previous dysplastic lesion | Probable incomplete resection of a previously identified advanced adenoma from the same bowel segment as the subsequently diagnosed CRC, and there was no endoscopic/histological confirmation of complete resection | 0 [0.0%] |

| [b] Detected advanced lesion, not endoscopically resected | An advanced adenoma was identified in the same bowel segment, and it was not endoscopically resected | 9 [40.9%] |

| [c] Possible missed advanced lesion with previous adequate examination | No advanced adenoma was identified in the same bowel segment and there is evidence of caecal intubation [photo-documented or written in the report]; and bowel preparation was adequate | 8 [36.4%] |

| [d] Possible missed advanced lesion with previous inadequate examination | No advanced adenoma was identified in the same bowel segment and there is no evidence of caecal intubation [photo-documented or written in the report]; and bowel preparation was inadequate | 3 [13.6%] |

| [e] Other, e.g. deviation from planned management pathway | Deviation from planned management pathway: non-compliant to recommended surveillance interval or patient postponed or declined colectomy recommended for advanced lesion | 9 [40.9%] |

| WEO categorization of causative factors . | Explanation of category . | N [%] . |

|---|---|---|

| [a] Probable incomplete resection of previous dysplastic lesion | Probable incomplete resection of a previously identified advanced adenoma from the same bowel segment as the subsequently diagnosed CRC, and there was no endoscopic/histological confirmation of complete resection | 0 [0.0%] |

| [b] Detected advanced lesion, not endoscopically resected | An advanced adenoma was identified in the same bowel segment, and it was not endoscopically resected | 9 [40.9%] |

| [c] Possible missed advanced lesion with previous adequate examination | No advanced adenoma was identified in the same bowel segment and there is evidence of caecal intubation [photo-documented or written in the report]; and bowel preparation was adequate | 8 [36.4%] |

| [d] Possible missed advanced lesion with previous inadequate examination | No advanced adenoma was identified in the same bowel segment and there is no evidence of caecal intubation [photo-documented or written in the report]; and bowel preparation was inadequate | 3 [13.6%] |

| [e] Other, e.g. deviation from planned management pathway | Deviation from planned management pathway: non-compliant to recommended surveillance interval or patient postponed or declined colectomy recommended for advanced lesion | 9 [40.9%] |

PCCRC, post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer. Advanced adenoma = greater than 1 cm in size and/or villous and/or containing high-grade dysplasia.

World Endoscopy Organisation [WEO] categorization of potential causative factors for PCCRCs

| WEO categorization of causative factors . | Explanation of category . | N [%] . |

|---|---|---|

| [a] Probable incomplete resection of previous dysplastic lesion | Probable incomplete resection of a previously identified advanced adenoma from the same bowel segment as the subsequently diagnosed CRC, and there was no endoscopic/histological confirmation of complete resection | 0 [0.0%] |

| [b] Detected advanced lesion, not endoscopically resected | An advanced adenoma was identified in the same bowel segment, and it was not endoscopically resected | 9 [40.9%] |

| [c] Possible missed advanced lesion with previous adequate examination | No advanced adenoma was identified in the same bowel segment and there is evidence of caecal intubation [photo-documented or written in the report]; and bowel preparation was adequate | 8 [36.4%] |

| [d] Possible missed advanced lesion with previous inadequate examination | No advanced adenoma was identified in the same bowel segment and there is no evidence of caecal intubation [photo-documented or written in the report]; and bowel preparation was inadequate | 3 [13.6%] |

| [e] Other, e.g. deviation from planned management pathway | Deviation from planned management pathway: non-compliant to recommended surveillance interval or patient postponed or declined colectomy recommended for advanced lesion | 9 [40.9%] |

| WEO categorization of causative factors . | Explanation of category . | N [%] . |

|---|---|---|

| [a] Probable incomplete resection of previous dysplastic lesion | Probable incomplete resection of a previously identified advanced adenoma from the same bowel segment as the subsequently diagnosed CRC, and there was no endoscopic/histological confirmation of complete resection | 0 [0.0%] |

| [b] Detected advanced lesion, not endoscopically resected | An advanced adenoma was identified in the same bowel segment, and it was not endoscopically resected | 9 [40.9%] |

| [c] Possible missed advanced lesion with previous adequate examination | No advanced adenoma was identified in the same bowel segment and there is evidence of caecal intubation [photo-documented or written in the report]; and bowel preparation was adequate | 8 [36.4%] |

| [d] Possible missed advanced lesion with previous inadequate examination | No advanced adenoma was identified in the same bowel segment and there is no evidence of caecal intubation [photo-documented or written in the report]; and bowel preparation was inadequate | 3 [13.6%] |

| [e] Other, e.g. deviation from planned management pathway | Deviation from planned management pathway: non-compliant to recommended surveillance interval or patient postponed or declined colectomy recommended for advanced lesion | 9 [40.9%] |

PCCRC, post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer. Advanced adenoma = greater than 1 cm in size and/or villous and/or containing high-grade dysplasia.

2.2. Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical software [version 24, IBM] to provide descriptive statistics. All non-parametric continuous variables are reported as medians with interquartile ranges [IQRs] or ranges and parametric continuous variables are reported as means with standard deviation. Categorical variables are described as raw numbers or percentages and comparison of groups has been made using Fisher’s exact test. Probability (p) values <0.05 signify statistical significance.

3. Results

There were 58 IBD patients with colorectal carcinomas diagnosed in the study period. Twenty-two cases [37.9%] were excluded [Figure 1]. Of the remaining 36 cases, 61.1% [n = 22] were defined as PCCRCs whereas only 38.9% [n = 14] were defined as surveillance-detected CRCs. Most of the cancers [77.8%; n = 28/36] developed in patients who met criteria for annual surveillance due to high cancer risk factors. No cancers developed in patients with UC proctitis but five developed in patients despite low-risk left-sided UC or limited quiescent Crohn’s colitis [<50% involvement of the colon]. Patient demographics and disease characteristics of included cases are reported in Table 2.

IBD cancer patient demographics and disease characteristics from all four centres

| Patient demographics and disease characteristics . | PCCRCs [n = 22] . | Surveillance-detected cancers [n = 14] . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at time of cancer diagnosis [years] | 61.5 [IQR 38.8–74.3] | 58.0 [IQR 49.0–68.0] | 0.470 |

| Median duration of IBD at cancer diagnosis [years] | 20.0 [IQR 15.0–25.3] | 29.0 [IQR 15.0–32.0] | 0.301 |

| Male gender | 63.6% [n = 14/22] | 64.3% [n = 9/14] | 0.968 |

| Non-Caucasian ethnicity | 27.3% [n = 6/22] | 50.0% [n = 7/14] | 0.166 |

| IBD type | |||

| Ulcerative colitis | 72.7% [n = 16/22] | 85.7% [n = 12/14] | 0.441 |

| Crohn’s disease | 27.3% [n = 6/22] | 14.3% [n = 2/14] | |

| History of extensive colitis [extending proximal to splenic flexure in ulcerative colitis and > 50% of the colon in Crohn’s disease] | 77.3% [n = 17/22] | 84.6% [n = 11/13] | 0.689 |

| Medication use at time of CRC diagnosis | |||

| 5-Aminosalicylate | 75.0% [n = 15/20] | 81.8% [n = 9/11] | |

| Immunomodulator | 50.0% [n = 10/20] | 40.0% [n = 4/10] | |

| Biologic | 25.0% [n = 5/20] | 0.0% [n = 0/11] | 0.133 |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 13.6% [n = 3/22] | 0.0% [n = 0/14] | 0.537 |

| Presence of multiple post-inflammatory polyps | 38.1% [n = 8/21] | 58.3% [n = 7/12] | 0.261 |

| Previous or existing stricture within last 5 years | 14.3% [n = 3/21] | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | — |

| Previously diagnosed dysplasia within last 5 years | 47.6% [n = 10/21] | 66.7% [n = 8/12] | 0.290 |

| Had extensive moderate–severe active inflammation on their last cancer-negative surveillance colonoscopy | 50.0% [n = 11/22] | 28.6% [n = 4/14] | 0.204 |

| High-risk surveillance interval categorization based on risk factors [i.e. meets criteria for annual surveillance] | 81.8% [n = 18/22] | 71.4% [n = 10/14] | 0.683 |

| Investigation mode of cancer diagnosis | |||

| Endoscopy | 63.6% [n = 14/22] | 28.6% [n = 4/14] | 0.172 |

| Surgery | 27.3% [n = 6/22] | 64.3% [n = 9/14] | |

| Radiology | 9.1% [n = 2/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | |

| Location of CRC | |||

| Distal colon/rectum | 63.6% [n = 14/22] | 64.3% [n = 9/14] | 0.968 |

| Proximal colon | 36.4% [n = 8/22] | 35.7% [n = 5/14] | |

| TNM stage | |||

| Early stage [I–II] | 54.5% [n = 12/22] | 71.4% [n = 10/14] | 0.311 |

| Advanced stage [III–IV] | 45.5% [n = 10/22] | 28.6% [n = 4/14] | |

| Cancer-related deaths | 40.9% [n = 9/22] | 14.3% [n = 2/14] | 0.142 |

| Median survival time [months] | 38.0 [IQR 14.8–63.0] | 51.0 [IQR 36.0–69.5] | 0.346 |

| Patient demographics and disease characteristics . | PCCRCs [n = 22] . | Surveillance-detected cancers [n = 14] . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at time of cancer diagnosis [years] | 61.5 [IQR 38.8–74.3] | 58.0 [IQR 49.0–68.0] | 0.470 |

| Median duration of IBD at cancer diagnosis [years] | 20.0 [IQR 15.0–25.3] | 29.0 [IQR 15.0–32.0] | 0.301 |

| Male gender | 63.6% [n = 14/22] | 64.3% [n = 9/14] | 0.968 |

| Non-Caucasian ethnicity | 27.3% [n = 6/22] | 50.0% [n = 7/14] | 0.166 |

| IBD type | |||

| Ulcerative colitis | 72.7% [n = 16/22] | 85.7% [n = 12/14] | 0.441 |

| Crohn’s disease | 27.3% [n = 6/22] | 14.3% [n = 2/14] | |

| History of extensive colitis [extending proximal to splenic flexure in ulcerative colitis and > 50% of the colon in Crohn’s disease] | 77.3% [n = 17/22] | 84.6% [n = 11/13] | 0.689 |

| Medication use at time of CRC diagnosis | |||

| 5-Aminosalicylate | 75.0% [n = 15/20] | 81.8% [n = 9/11] | |

| Immunomodulator | 50.0% [n = 10/20] | 40.0% [n = 4/10] | |

| Biologic | 25.0% [n = 5/20] | 0.0% [n = 0/11] | 0.133 |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 13.6% [n = 3/22] | 0.0% [n = 0/14] | 0.537 |

| Presence of multiple post-inflammatory polyps | 38.1% [n = 8/21] | 58.3% [n = 7/12] | 0.261 |

| Previous or existing stricture within last 5 years | 14.3% [n = 3/21] | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | — |

| Previously diagnosed dysplasia within last 5 years | 47.6% [n = 10/21] | 66.7% [n = 8/12] | 0.290 |

| Had extensive moderate–severe active inflammation on their last cancer-negative surveillance colonoscopy | 50.0% [n = 11/22] | 28.6% [n = 4/14] | 0.204 |

| High-risk surveillance interval categorization based on risk factors [i.e. meets criteria for annual surveillance] | 81.8% [n = 18/22] | 71.4% [n = 10/14] | 0.683 |

| Investigation mode of cancer diagnosis | |||

| Endoscopy | 63.6% [n = 14/22] | 28.6% [n = 4/14] | 0.172 |

| Surgery | 27.3% [n = 6/22] | 64.3% [n = 9/14] | |

| Radiology | 9.1% [n = 2/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | |

| Location of CRC | |||

| Distal colon/rectum | 63.6% [n = 14/22] | 64.3% [n = 9/14] | 0.968 |

| Proximal colon | 36.4% [n = 8/22] | 35.7% [n = 5/14] | |

| TNM stage | |||

| Early stage [I–II] | 54.5% [n = 12/22] | 71.4% [n = 10/14] | 0.311 |

| Advanced stage [III–IV] | 45.5% [n = 10/22] | 28.6% [n = 4/14] | |

| Cancer-related deaths | 40.9% [n = 9/22] | 14.3% [n = 2/14] | 0.142 |

| Median survival time [months] | 38.0 [IQR 14.8–63.0] | 51.0 [IQR 36.0–69.5] | 0.346 |

PCCRC, post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; TNM, tumour, node, and metastasis; IQR, interquartile range.

IBD cancer patient demographics and disease characteristics from all four centres

| Patient demographics and disease characteristics . | PCCRCs [n = 22] . | Surveillance-detected cancers [n = 14] . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at time of cancer diagnosis [years] | 61.5 [IQR 38.8–74.3] | 58.0 [IQR 49.0–68.0] | 0.470 |

| Median duration of IBD at cancer diagnosis [years] | 20.0 [IQR 15.0–25.3] | 29.0 [IQR 15.0–32.0] | 0.301 |

| Male gender | 63.6% [n = 14/22] | 64.3% [n = 9/14] | 0.968 |

| Non-Caucasian ethnicity | 27.3% [n = 6/22] | 50.0% [n = 7/14] | 0.166 |

| IBD type | |||

| Ulcerative colitis | 72.7% [n = 16/22] | 85.7% [n = 12/14] | 0.441 |

| Crohn’s disease | 27.3% [n = 6/22] | 14.3% [n = 2/14] | |

| History of extensive colitis [extending proximal to splenic flexure in ulcerative colitis and > 50% of the colon in Crohn’s disease] | 77.3% [n = 17/22] | 84.6% [n = 11/13] | 0.689 |

| Medication use at time of CRC diagnosis | |||

| 5-Aminosalicylate | 75.0% [n = 15/20] | 81.8% [n = 9/11] | |

| Immunomodulator | 50.0% [n = 10/20] | 40.0% [n = 4/10] | |

| Biologic | 25.0% [n = 5/20] | 0.0% [n = 0/11] | 0.133 |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 13.6% [n = 3/22] | 0.0% [n = 0/14] | 0.537 |

| Presence of multiple post-inflammatory polyps | 38.1% [n = 8/21] | 58.3% [n = 7/12] | 0.261 |

| Previous or existing stricture within last 5 years | 14.3% [n = 3/21] | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | — |

| Previously diagnosed dysplasia within last 5 years | 47.6% [n = 10/21] | 66.7% [n = 8/12] | 0.290 |

| Had extensive moderate–severe active inflammation on their last cancer-negative surveillance colonoscopy | 50.0% [n = 11/22] | 28.6% [n = 4/14] | 0.204 |

| High-risk surveillance interval categorization based on risk factors [i.e. meets criteria for annual surveillance] | 81.8% [n = 18/22] | 71.4% [n = 10/14] | 0.683 |

| Investigation mode of cancer diagnosis | |||

| Endoscopy | 63.6% [n = 14/22] | 28.6% [n = 4/14] | 0.172 |

| Surgery | 27.3% [n = 6/22] | 64.3% [n = 9/14] | |

| Radiology | 9.1% [n = 2/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | |

| Location of CRC | |||

| Distal colon/rectum | 63.6% [n = 14/22] | 64.3% [n = 9/14] | 0.968 |

| Proximal colon | 36.4% [n = 8/22] | 35.7% [n = 5/14] | |

| TNM stage | |||

| Early stage [I–II] | 54.5% [n = 12/22] | 71.4% [n = 10/14] | 0.311 |

| Advanced stage [III–IV] | 45.5% [n = 10/22] | 28.6% [n = 4/14] | |

| Cancer-related deaths | 40.9% [n = 9/22] | 14.3% [n = 2/14] | 0.142 |

| Median survival time [months] | 38.0 [IQR 14.8–63.0] | 51.0 [IQR 36.0–69.5] | 0.346 |

| Patient demographics and disease characteristics . | PCCRCs [n = 22] . | Surveillance-detected cancers [n = 14] . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at time of cancer diagnosis [years] | 61.5 [IQR 38.8–74.3] | 58.0 [IQR 49.0–68.0] | 0.470 |

| Median duration of IBD at cancer diagnosis [years] | 20.0 [IQR 15.0–25.3] | 29.0 [IQR 15.0–32.0] | 0.301 |

| Male gender | 63.6% [n = 14/22] | 64.3% [n = 9/14] | 0.968 |

| Non-Caucasian ethnicity | 27.3% [n = 6/22] | 50.0% [n = 7/14] | 0.166 |

| IBD type | |||

| Ulcerative colitis | 72.7% [n = 16/22] | 85.7% [n = 12/14] | 0.441 |

| Crohn’s disease | 27.3% [n = 6/22] | 14.3% [n = 2/14] | |

| History of extensive colitis [extending proximal to splenic flexure in ulcerative colitis and > 50% of the colon in Crohn’s disease] | 77.3% [n = 17/22] | 84.6% [n = 11/13] | 0.689 |

| Medication use at time of CRC diagnosis | |||

| 5-Aminosalicylate | 75.0% [n = 15/20] | 81.8% [n = 9/11] | |

| Immunomodulator | 50.0% [n = 10/20] | 40.0% [n = 4/10] | |

| Biologic | 25.0% [n = 5/20] | 0.0% [n = 0/11] | 0.133 |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 13.6% [n = 3/22] | 0.0% [n = 0/14] | 0.537 |

| Presence of multiple post-inflammatory polyps | 38.1% [n = 8/21] | 58.3% [n = 7/12] | 0.261 |

| Previous or existing stricture within last 5 years | 14.3% [n = 3/21] | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | — |

| Previously diagnosed dysplasia within last 5 years | 47.6% [n = 10/21] | 66.7% [n = 8/12] | 0.290 |

| Had extensive moderate–severe active inflammation on their last cancer-negative surveillance colonoscopy | 50.0% [n = 11/22] | 28.6% [n = 4/14] | 0.204 |

| High-risk surveillance interval categorization based on risk factors [i.e. meets criteria for annual surveillance] | 81.8% [n = 18/22] | 71.4% [n = 10/14] | 0.683 |

| Investigation mode of cancer diagnosis | |||

| Endoscopy | 63.6% [n = 14/22] | 28.6% [n = 4/14] | 0.172 |

| Surgery | 27.3% [n = 6/22] | 64.3% [n = 9/14] | |

| Radiology | 9.1% [n = 2/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | |

| Location of CRC | |||

| Distal colon/rectum | 63.6% [n = 14/22] | 64.3% [n = 9/14] | 0.968 |

| Proximal colon | 36.4% [n = 8/22] | 35.7% [n = 5/14] | |

| TNM stage | |||

| Early stage [I–II] | 54.5% [n = 12/22] | 71.4% [n = 10/14] | 0.311 |

| Advanced stage [III–IV] | 45.5% [n = 10/22] | 28.6% [n = 4/14] | |

| Cancer-related deaths | 40.9% [n = 9/22] | 14.3% [n = 2/14] | 0.142 |

| Median survival time [months] | 38.0 [IQR 14.8–63.0] | 51.0 [IQR 36.0–69.5] | 0.346 |

PCCRC, post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; TNM, tumour, node, and metastasis; IQR, interquartile range.

![Flow chart of included and excluded inflammatory bowel disease cancers and breakdown of post-colonoscopy cancers [PCCRCs] and surveillance-detected cancers.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ecco-jcc/18/5/10.1093_ecco-jcc_jjad189/1/m_jjad189_fig1.jpeg?Expires=1748172214&Signature=A7kp1iwfdWa~9AdgtGWOCi32EL8rmhHH-HN19wBaaJJhyUFQolu6FCbp3TQPXwYFd55lvYawP7s9lLT2xgqtB9rRLY6kdBmrGGV8rtYJVUwAes-DudA0WKxo~xqFyZsLQ9xeWR~TEQgOIB1-PRrWth-zgyRIjpKYZalA6xKs5p86HF0oZGF9ucyqQmd7pAfispXSY62D8xNt6CZI2fCPpFCT~HQHF9yKMwT9BXo2NuXfza90N1TVh-CBdL67PdzL5VshNQLrEIvr1qpXaH8urtQgqtD~baWa6a7wpPqksQuuErPZuwV8IFsCSVEpWJ7M34OSsBS-T1aEGryQaTxviQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Flow chart of included and excluded inflammatory bowel disease cancers and breakdown of post-colonoscopy cancers [PCCRCs] and surveillance-detected cancers.

*Interval post-colonoscopy cancers [PCCRCs] = PCCRC diagnosed before next recommended surveillance interval.

**Non-interval post-colonoscopy cancers [PCCRCs]: Type A = PCCRC diagnosed at time of next recommended surveillance interval; Type B = PCCRC diagnosed after time of next recommended surveillance interval; Type C = no surveillance interval recommended.

3.1. Quality of last cancer-negative surveillance colonoscopy

Table 3 demonstrates the features of the last cancer-negative surveillance colonoscopy that was performed before either a PCCRC or a surveillance-detected CRC was diagnosed. For 72.7% [n = 24/33] of the total IBD CRC cases, dysplasia or a lesion suspicious for dysplasia was found by the endoscopist during the last surveillance colonoscopy in the same colonic segment prior to where the cancer was subsequently diagnosed. None of these lesions were considered endoscopically resectable and led to a cancer diagnosis after prompting a referral for elective surgery in 54.2% [n = 13/24] or another endoscopic examination in 45.8% [n = 11/24]. In the surveillance-detected CRC cohort, all these interventions [n = 12] were performed within 6 months.

Characteristics of the last cancer-negative surveillance colonoscopy performed before the cancer diagnosis across all four centres.

| Characteristics of the last cancer-negative surveillance colonoscopy . | PCCRCs, N [%] or median [IQR] . | Surveillance-detected CRCs, N [%] or median [IQR] . | p-value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median duration from last surveillance colonoscopy to cancer diagnosis [months] | 15.0 [IQR 10.0–27.3] | 2.0 [IQR 1.0–5.0] | 0.001 | ||

| Median interval between penultimate and last surveillance colonoscopy [months] | 14.5 [IQR 8.5–27.3] | 17.0 [IQR 6.0–21.0] | 0.530 | ||

| Inappropriately delayed surveillance interval before or after last surveillance colonoscopy [delayed by at least 2 months from recommended surveillance interval due to patient non-attendance, endoscopist non-compliance with recommendations, administrative booking delays] | 59.1% [n = 13/22] | 53.8% [n = 7/13] | 0.762 | ||

| Inadequate bowel preparation | 9.1% [n = 2/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | 1.000 | ||

| Dye spray chromoendoscopy use | |||||

| Yes | 45.5% [n = 10/22] | 78.6% [n = 11/14] | 0.049 | ||

| No [due to inadequate bowel preparation or active inflammation] | 45.5% [n = 10/22] | 14.3% [n = 2/14] | |||

| No [reason not clear] | 9.1% [n = 2/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | |||

| Endoscopist expertise | |||||

| Consultant endoscopist with specialist expertise in complex polypectomy | 50.0% [n = 11/22] | 42.9% [n = 6/14] | — | ||

| Other consultant endoscopist | 31.8% [n = 7/22] | 50.0% [n = 7/14] | |||

| Non-consultant endoscopist | 18.2% [n = 4/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | |||

| Incomplete colonoscopic examination to caecum or anastomosis [due to poor bowel preparation, impassable stricture, technical difficulty, or unclear reason] | 13.6% [n = 3/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | 1.000 | ||

| Rectal retroflexion photo-documented | 68.2% [n = 15/22] | 75.0% [n = 9/12] | 1.000 | ||

| Histologically active inflammation at the location of subsequent cancer | |||||

| Quiescent/normal | 47.6% [n = 10/21] | 35.7% [n = 5/14] | — | ||

| Mild | 23.8% [n = 5/21] | 42.9% [n = 6/14] | |||

| Moderate | 28.6% [n = 6/21] | 14.3% [n = 2/14] | |||

| Severe | 0.0% [n = 0/21] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | |||

| Lesion detected within colonic segment of subsequent cancer | 54.5% [n = 12/22] | 85.7% [n = 12/14] | 0.076 | ||

| Morphology of lesion detected within colonic segment of subsequent cancer | |||||

| Polypoid | 33.3% [n = 4/12] | 25.0% [n = 3/12] | — | ||

| Non-polypoid | 50.0% [n = 6/12] | 66.7% [n = 8/12] | |||

| Stricture | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | 0.0% [n = 0/12] | |||

| Invisible [detected on random biopsy] | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | |||

| Histology of visible lesions biopsied within colonic segment of subsequent cancer: | |||||

| Low-grade dysplasia [LGD] | 41.7% [n = 5/12] | 50.0% [n = 6/12] | — | ||

| High-grade dysplasia [HGD] | 33.3% [n = 4/12] | 41.7% [n = 5/12] | |||

| Regenerative/inflammatory/no dysplasia | 25.0% [n = 3/12] | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | |||

| Visible lesion at colonoscopy located at site of subsequent cancer, detected and/or resected by: | N = 11 Detected: | Resected: | N = 11 Detected: | Resected: | — |

| Endoscopist with specialist expertise in complex polypectomy | 72.7% [n = 8] | 0.0% | 54.5% [n = 6] | 0.0% | |

| Other consultant endoscopist | 27.3% [n = 3] | 0.0% | 45.5% [n = 5] | 0.0% | |

| Characteristics of the last cancer-negative surveillance colonoscopy . | PCCRCs, N [%] or median [IQR] . | Surveillance-detected CRCs, N [%] or median [IQR] . | p-value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median duration from last surveillance colonoscopy to cancer diagnosis [months] | 15.0 [IQR 10.0–27.3] | 2.0 [IQR 1.0–5.0] | 0.001 | ||

| Median interval between penultimate and last surveillance colonoscopy [months] | 14.5 [IQR 8.5–27.3] | 17.0 [IQR 6.0–21.0] | 0.530 | ||

| Inappropriately delayed surveillance interval before or after last surveillance colonoscopy [delayed by at least 2 months from recommended surveillance interval due to patient non-attendance, endoscopist non-compliance with recommendations, administrative booking delays] | 59.1% [n = 13/22] | 53.8% [n = 7/13] | 0.762 | ||

| Inadequate bowel preparation | 9.1% [n = 2/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | 1.000 | ||

| Dye spray chromoendoscopy use | |||||

| Yes | 45.5% [n = 10/22] | 78.6% [n = 11/14] | 0.049 | ||

| No [due to inadequate bowel preparation or active inflammation] | 45.5% [n = 10/22] | 14.3% [n = 2/14] | |||

| No [reason not clear] | 9.1% [n = 2/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | |||

| Endoscopist expertise | |||||

| Consultant endoscopist with specialist expertise in complex polypectomy | 50.0% [n = 11/22] | 42.9% [n = 6/14] | — | ||

| Other consultant endoscopist | 31.8% [n = 7/22] | 50.0% [n = 7/14] | |||

| Non-consultant endoscopist | 18.2% [n = 4/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | |||

| Incomplete colonoscopic examination to caecum or anastomosis [due to poor bowel preparation, impassable stricture, technical difficulty, or unclear reason] | 13.6% [n = 3/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | 1.000 | ||

| Rectal retroflexion photo-documented | 68.2% [n = 15/22] | 75.0% [n = 9/12] | 1.000 | ||

| Histologically active inflammation at the location of subsequent cancer | |||||

| Quiescent/normal | 47.6% [n = 10/21] | 35.7% [n = 5/14] | — | ||

| Mild | 23.8% [n = 5/21] | 42.9% [n = 6/14] | |||

| Moderate | 28.6% [n = 6/21] | 14.3% [n = 2/14] | |||

| Severe | 0.0% [n = 0/21] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | |||

| Lesion detected within colonic segment of subsequent cancer | 54.5% [n = 12/22] | 85.7% [n = 12/14] | 0.076 | ||

| Morphology of lesion detected within colonic segment of subsequent cancer | |||||

| Polypoid | 33.3% [n = 4/12] | 25.0% [n = 3/12] | — | ||

| Non-polypoid | 50.0% [n = 6/12] | 66.7% [n = 8/12] | |||

| Stricture | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | 0.0% [n = 0/12] | |||

| Invisible [detected on random biopsy] | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | |||

| Histology of visible lesions biopsied within colonic segment of subsequent cancer: | |||||

| Low-grade dysplasia [LGD] | 41.7% [n = 5/12] | 50.0% [n = 6/12] | — | ||

| High-grade dysplasia [HGD] | 33.3% [n = 4/12] | 41.7% [n = 5/12] | |||

| Regenerative/inflammatory/no dysplasia | 25.0% [n = 3/12] | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | |||

| Visible lesion at colonoscopy located at site of subsequent cancer, detected and/or resected by: | N = 11 Detected: | Resected: | N = 11 Detected: | Resected: | — |

| Endoscopist with specialist expertise in complex polypectomy | 72.7% [n = 8] | 0.0% | 54.5% [n = 6] | 0.0% | |

| Other consultant endoscopist | 27.3% [n = 3] | 0.0% | 45.5% [n = 5] | 0.0% | |

PCCRC, post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer; IQR, interquartile range.

Characteristics of the last cancer-negative surveillance colonoscopy performed before the cancer diagnosis across all four centres.

| Characteristics of the last cancer-negative surveillance colonoscopy . | PCCRCs, N [%] or median [IQR] . | Surveillance-detected CRCs, N [%] or median [IQR] . | p-value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median duration from last surveillance colonoscopy to cancer diagnosis [months] | 15.0 [IQR 10.0–27.3] | 2.0 [IQR 1.0–5.0] | 0.001 | ||

| Median interval between penultimate and last surveillance colonoscopy [months] | 14.5 [IQR 8.5–27.3] | 17.0 [IQR 6.0–21.0] | 0.530 | ||

| Inappropriately delayed surveillance interval before or after last surveillance colonoscopy [delayed by at least 2 months from recommended surveillance interval due to patient non-attendance, endoscopist non-compliance with recommendations, administrative booking delays] | 59.1% [n = 13/22] | 53.8% [n = 7/13] | 0.762 | ||

| Inadequate bowel preparation | 9.1% [n = 2/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | 1.000 | ||

| Dye spray chromoendoscopy use | |||||

| Yes | 45.5% [n = 10/22] | 78.6% [n = 11/14] | 0.049 | ||

| No [due to inadequate bowel preparation or active inflammation] | 45.5% [n = 10/22] | 14.3% [n = 2/14] | |||

| No [reason not clear] | 9.1% [n = 2/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | |||

| Endoscopist expertise | |||||

| Consultant endoscopist with specialist expertise in complex polypectomy | 50.0% [n = 11/22] | 42.9% [n = 6/14] | — | ||

| Other consultant endoscopist | 31.8% [n = 7/22] | 50.0% [n = 7/14] | |||

| Non-consultant endoscopist | 18.2% [n = 4/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | |||

| Incomplete colonoscopic examination to caecum or anastomosis [due to poor bowel preparation, impassable stricture, technical difficulty, or unclear reason] | 13.6% [n = 3/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | 1.000 | ||

| Rectal retroflexion photo-documented | 68.2% [n = 15/22] | 75.0% [n = 9/12] | 1.000 | ||

| Histologically active inflammation at the location of subsequent cancer | |||||

| Quiescent/normal | 47.6% [n = 10/21] | 35.7% [n = 5/14] | — | ||

| Mild | 23.8% [n = 5/21] | 42.9% [n = 6/14] | |||

| Moderate | 28.6% [n = 6/21] | 14.3% [n = 2/14] | |||

| Severe | 0.0% [n = 0/21] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | |||

| Lesion detected within colonic segment of subsequent cancer | 54.5% [n = 12/22] | 85.7% [n = 12/14] | 0.076 | ||

| Morphology of lesion detected within colonic segment of subsequent cancer | |||||

| Polypoid | 33.3% [n = 4/12] | 25.0% [n = 3/12] | — | ||

| Non-polypoid | 50.0% [n = 6/12] | 66.7% [n = 8/12] | |||

| Stricture | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | 0.0% [n = 0/12] | |||

| Invisible [detected on random biopsy] | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | |||

| Histology of visible lesions biopsied within colonic segment of subsequent cancer: | |||||

| Low-grade dysplasia [LGD] | 41.7% [n = 5/12] | 50.0% [n = 6/12] | — | ||

| High-grade dysplasia [HGD] | 33.3% [n = 4/12] | 41.7% [n = 5/12] | |||

| Regenerative/inflammatory/no dysplasia | 25.0% [n = 3/12] | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | |||

| Visible lesion at colonoscopy located at site of subsequent cancer, detected and/or resected by: | N = 11 Detected: | Resected: | N = 11 Detected: | Resected: | — |

| Endoscopist with specialist expertise in complex polypectomy | 72.7% [n = 8] | 0.0% | 54.5% [n = 6] | 0.0% | |

| Other consultant endoscopist | 27.3% [n = 3] | 0.0% | 45.5% [n = 5] | 0.0% | |

| Characteristics of the last cancer-negative surveillance colonoscopy . | PCCRCs, N [%] or median [IQR] . | Surveillance-detected CRCs, N [%] or median [IQR] . | p-value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median duration from last surveillance colonoscopy to cancer diagnosis [months] | 15.0 [IQR 10.0–27.3] | 2.0 [IQR 1.0–5.0] | 0.001 | ||

| Median interval between penultimate and last surveillance colonoscopy [months] | 14.5 [IQR 8.5–27.3] | 17.0 [IQR 6.0–21.0] | 0.530 | ||

| Inappropriately delayed surveillance interval before or after last surveillance colonoscopy [delayed by at least 2 months from recommended surveillance interval due to patient non-attendance, endoscopist non-compliance with recommendations, administrative booking delays] | 59.1% [n = 13/22] | 53.8% [n = 7/13] | 0.762 | ||

| Inadequate bowel preparation | 9.1% [n = 2/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | 1.000 | ||

| Dye spray chromoendoscopy use | |||||

| Yes | 45.5% [n = 10/22] | 78.6% [n = 11/14] | 0.049 | ||

| No [due to inadequate bowel preparation or active inflammation] | 45.5% [n = 10/22] | 14.3% [n = 2/14] | |||

| No [reason not clear] | 9.1% [n = 2/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | |||

| Endoscopist expertise | |||||

| Consultant endoscopist with specialist expertise in complex polypectomy | 50.0% [n = 11/22] | 42.9% [n = 6/14] | — | ||

| Other consultant endoscopist | 31.8% [n = 7/22] | 50.0% [n = 7/14] | |||

| Non-consultant endoscopist | 18.2% [n = 4/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | |||

| Incomplete colonoscopic examination to caecum or anastomosis [due to poor bowel preparation, impassable stricture, technical difficulty, or unclear reason] | 13.6% [n = 3/22] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | 1.000 | ||

| Rectal retroflexion photo-documented | 68.2% [n = 15/22] | 75.0% [n = 9/12] | 1.000 | ||

| Histologically active inflammation at the location of subsequent cancer | |||||

| Quiescent/normal | 47.6% [n = 10/21] | 35.7% [n = 5/14] | — | ||

| Mild | 23.8% [n = 5/21] | 42.9% [n = 6/14] | |||

| Moderate | 28.6% [n = 6/21] | 14.3% [n = 2/14] | |||

| Severe | 0.0% [n = 0/21] | 7.1% [n = 1/14] | |||

| Lesion detected within colonic segment of subsequent cancer | 54.5% [n = 12/22] | 85.7% [n = 12/14] | 0.076 | ||

| Morphology of lesion detected within colonic segment of subsequent cancer | |||||

| Polypoid | 33.3% [n = 4/12] | 25.0% [n = 3/12] | — | ||

| Non-polypoid | 50.0% [n = 6/12] | 66.7% [n = 8/12] | |||

| Stricture | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | 0.0% [n = 0/12] | |||

| Invisible [detected on random biopsy] | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | |||

| Histology of visible lesions biopsied within colonic segment of subsequent cancer: | |||||

| Low-grade dysplasia [LGD] | 41.7% [n = 5/12] | 50.0% [n = 6/12] | — | ||

| High-grade dysplasia [HGD] | 33.3% [n = 4/12] | 41.7% [n = 5/12] | |||

| Regenerative/inflammatory/no dysplasia | 25.0% [n = 3/12] | 8.3% [n = 1/12] | |||

| Visible lesion at colonoscopy located at site of subsequent cancer, detected and/or resected by: | N = 11 Detected: | Resected: | N = 11 Detected: | Resected: | — |

| Endoscopist with specialist expertise in complex polypectomy | 72.7% [n = 8] | 0.0% | 54.5% [n = 6] | 0.0% | |

| Other consultant endoscopist | 27.3% [n = 3] | 0.0% | 45.5% [n = 5] | 0.0% | |

PCCRC, post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer; IQR, interquartile range.

Figure 1 presents the numbers of PCCRCs that were considered interval [n = 3] or non-interval PCCRCs [n = 19]. The interval PCCRCs were found before the next recommended surveillance interval due to symptoms prompting endoscopic examination; two cancers were detected within strictures. Most of the non-interval PCCRCs were considered type B [n = 12], that is the cancers were detected after the recommended surveillance interval due to clinician, patient or service delays. Five patients with non-interval type A PCCRCs were having regular surveillance for previous dysplasia or primary sclerosing cholangitis and cancers were found at their next surveillance; three of these patients had declined recommended colectomy despite high-risk findings. No further surveillance was recommended after two patients were found to have high-grade dysplasia [non-interval type C PCCRCs] but cancers were detected after prolonged intervals to colectomy due to waiting list or clinician decision-making delays.

3.2. Causes contributing to the post-colonoscopy CRCs

The most common WEO-categorized causative factors of the 22 PCCRCs were attributed to the detection of an advanced dysplastic lesion which was not endoscopically resected [40.9%; n = 9/22] and/or where there was also a deviation from the planned management pathway [40.9%; n = 9/22]. Seven of the PCCRCs [31.8%; n = 7/22] were categorized as caused by both. No PCRCCs were felt to be due to incomplete resection of a previous dysplastic lesion.

3.2.1. Detected advanced lesion, not endoscopically resected [40.9%; n = 9/22]

Most [77.8%; n = 7/9] of the PCCRCs in this category were diagnosed at an early stage [TNM I–II]. Supplementary Figure S1 provides detailed examples of some of the case studies with the corresponding endoscopic images. All the patients met criteria to be in the high-risk annual surveillance category, due to previous diagnoses of dysplasia, a colonic stricture, or moderately active pancolitis. Most [77.8%; n = 7/9] of the last cancer-negative surveillance colonoscopies were performed by consultant endoscopists with specialist expertise in complex polypectomy. None of the lesions detected were considered endoscopically resectable and 88.9% [n = 8/9] were located within segments of actively inflamed mucosa. Histology revealed low-grade [55.5%; n = 5/9] or high-grade dysplasia [44.4%; n = 4/9]. The lesions were mainly areas of flat mucosal change, or flat elevated lateral spreading tumours that had undefined borders or looked ulcerated. Despite the recommendation for colectomy for all these patients, six patients either declined or delayed colectomy and only three patients proceeded to colectomy within a median of 10.5 months [IQR 9.3–12.5].

3.2.2. Possible missed lesion, adequate examination [36.4%; n = 8/22]

Supplementary Figure S2 details example cases. Three-quarters [n = 6/8] of these patients had high CRC risk factors and their last surveillance colonoscopies were performed by independent endoscopists without a declared subspecialist interest in complex polypectomy. Chromoendoscopy was not used in 62.5% [n = 5/8] due to the presence of active inflammation. The majority [87.5%; n = 7/8] of the CRCs were subsequently located in colonic segments with active inflammation or post-inflammatory change on their last cancer-negative surveillance colonoscopies. Only three endoscopists prompted treatment escalation despite finding active inflammation. A rectal stricture was not biopsied at the time of the last surveillance colonoscopy but 9 months later adenocarcinoma was detected on repeated biopsy. The majority [87.5%; n = 7/8] had inappropriately prolonged surveillance intervals either before or after their last surveillance colonoscopy.

3.2.3. Possible missed lesion, inadequate examination [13.6%; n = 3/22]

All these PCCRC cases were detected in the ascending colon or caecum. In two cases, the caecal pole was not fully visualized. None had dye spray chromoendoscopy due to either active inflammation or inadequate bowel preparation. Repeat examinations were either not attended by the patient or inappropriately scheduled for after 12 months.

3.2.4. Deviation from the planned surveillance/management pathway [40.9%; n = 9/22]

Although advanced unresectable dysplastic lesions were detected on colonoscopy, many patients declined or delayed a decision to proceed with a recommended colectomy [n = 6/9] and/or there were service/clinician delays in scheduling the colectomy or surveillance [n = 3/9].

4. Discussion

Contrary to previous literature this UK multicentre cohort study reports on IBD-associated cancers in an era where surveillance with high-definition imaging and dye spray chromoendoscopy was routine, and where in-depth root cause analyses have been performed using structured categorization recommended in the WEO consensus statement.3 The majority of the last surveillance colonoscopies prior to the PCCRC diagnoses were performed by consultant endoscopists and reported adequate bowel preparation and successful completion. Despite this, most of the cancers diagnosed were PCCRCs [61.1%] rather than surveillance-detected CRCs [38.9%] and resulted in greater CRC-related death [40.9% vs 14.3%]. In contrast, prior studies have suggested that a large proportion of IBD PCCRCs were caused by missed lesions due to inadequate bowel preparation.9,10

Most of the PCCRCs, according to the WEO categorization, developed in situations where [i] an endoscopically unresectable lesion was detected [40.9%], and/or [ii] there was a deviation from the planned management pathway [40.9%], or [iii] lesions were potentially missed as they were typically located within areas of active inflammation or post-inflammatory change [36.4%]. An earlier study from St Mark’s Hospital11 which examined 18 IBD-associated PCCRCs diagnosed between 2005 and 2013 found similar findings, despite including an older time-period with lower high-definition chromoendoscopy use and before BSG surveillance guidelines were introduced in 2010. Other studies of IBD interval or post-colonoscopy CRCs have also revealed similar causative factors: the presence of high cancer risk factors [e.g. previous dysplasia or active inflammation],10,12,13 presumed missed lesions,10,11,14 and inappropriate surveillance intervals.9,15

For the overall included CRC cohort, over half of the surveillance intervals before or after the last cancer-negative surveillance colonoscopy were inappropriately delayed, consistent with other larger studies on surveillance adherence.16 Appropriate patient, clinician, and administrative staff education and maintenance of a prospective surveillance database to allow time-dependent surveillance scheduling based on risk, including early repeats of inadequate colonoscopies, is necessary to overcome these delays. Active inflammation was present in most of the last surveillance procedures before a PCCRC was detected, which would have precluded dye spray chromoendoscopy use and optimal mucosal visualization. Therefore, more proactive activity assessment and medical therapy escalation before scheduling a surveillance colonoscopy might theoretically improve neoplasia detection.17–19

Frequently the PCCRCs in this study developed in lesions detected at colonoscopy that were unresectable rather than incompletely resected. These lesions were usually non-polypoid in morphology, ulcers, large inflammatory-looking polyps, or strictures. They often initially yielded negative, reactive atypia or indefinite for dysplasia histology on biopsy leading to repeated examination until more advanced neoplasia was detected. It is well documented in the literature that these types of lesion can harbour neoplasia.8,20,21 In this study, PCCRCs often also appeared in colonic segments with active inflammation or post-inflammatory regeneration without obvious visible discrete lesions. A prior history of colorectal neoplasia was common. This supports the established theory of the ‘field cancerization’ effect, whereby colonic inflammation drives clonal evolution of somatic cells with carcinogenic genetic changes, creating a field of cancer-primed tissue throughout the colon.22 Consequently, the colon appears to be susceptible to rapid progression of metachronous and multifocal invasive neoplasia despite only subtle changes detectable at the endoluminal surface.20,23 Increasingly, non-conventional types of dysplasia are being recognized which may be precursors for more aggressive intramucosal cancers which may not be detectable with superficial biopsies24 or are not biopsied as they are more frequently invisible.25,26 Emerging molecular biomarkers may therefore play a greater role in enhancing cancer risk stratification in the future.22,27

This study provides evidence that continuing education remains essential for all endoscopists who perform IBD colonoscopies. Departmental feedback with endoscopic images, formal endoscopist training28,29 [also accessible on the ECCO e-learning portal ‘Optic Endoscopy Advanced Training’], and artificial intelligence software30 may improve optical characterization of the subtle dysplastic lesions seen in IBD in the future. Strictures should be cross-sectionally evaluated using radiological imaging to exclude underlying mass lesions.8 Endoscopically unresectable but suspicious lesions should be biopsied extensively. If biopsies are negative for neoplasia, then prompt re-evaluation by an endoscopist with expertise in IBD dysplastic lesion assessment should be encouraged. Ensuring all IBD dysplasia diagnoses are referred for discussion in an IBD multidisciplinary team [MDT] meeting where colorectal surgeons and endoscopists, with specialist expertise in optical characterization and resectability assessment of dysplastic lesions, are present may also accelerate decision-making.

Most [83%] of the colonoscopies where a lesion may have been missed were performed by endoscopists without specialist expertise in both complex polypectomy and IBD chromoendoscopy surveillance, which highlights the importance of training in optical characterization of lesions seen in IBD. Most of the PCCRCs in this study occurred in patients with known high-risk factors for CRC development [81.8%] and therefore it is reasonable to recommend that their annual IBD surveillance is performed by endoscopists experienced in chromoendoscopy and lesion optical characterization. There is currently no accreditation requirement to determine expertise in IBD surveillance as there is for the UK Bowel Cancer Screening Programme [BCSP]. The lowest PCCRC rates for sporadic cancers in the general population are associated with BCSP-accredited endoscopists4 but expertise thresholds for IBD surveillance are yet to be validated.29,31

Patients with risk factors for CRC in addition to their colitis should be adequately counselled about the benefit of prophylactic colectomy. However, as reported in this study, many patients are reluctant to consider surgery. Many overestimate the protection that surveillance can offer them in reducing their CRC risk.32,33 Clinicians should be honest about the limitations of colonoscopic surveillance and quote institutional IBD PCCRC rates.

There are limitations due to the retrospective nature of this study. The method of patient identification was limited due to incomplete medical documentation and coding which may have led to some IBD CRCs being missed. Factors that affect the quality of the surveillance procedure such as withdrawal time were not recorded. Use of virtual chromoendoscopy could not be recorded as reliably as dye spray use. To allow root cause analysis, only IBD patients whose last surveillance was performed within the same English NHS Trust that the CRC was subsequently diagnosed in were included which would have underestimated the PCCRC rate. The WEO categorization algorithm to identify causal factors for PCCRCs, which has been designed for sporadic cancers, was also difficult to apply to IBD patients where atypical lesions are more common and do not always meet WEO criteria for an advanced adenoma [high-grade dysplasia, villous histology, and/or more than 1 cm in size]. Therefore, to make the WEO categorization algorithm more relevant to IBD, the definition for advanced adenoma might need to be extended to include, for example, multifocal low-grade dysplasia. Additionally, root cause analyses of IBD cancers detected more than 5 years after their last surveillance colonoscopy would have allowed further insights into whether these were truly ‘new’ cancers or occurred due to inappropriate delays for patients who qualified for 5-year surveillance intervals.

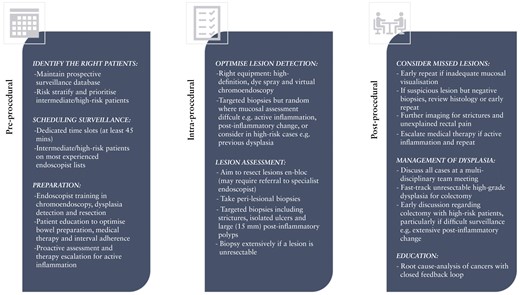

A summary of pre-, intra-, and post-procedural factors that can be addressed in current practice to improve the efficacy of surveillance are highlighted in Figure 2. This study, however, highlights the current limitations of even high-quality surveillance due to the aggressive nature of IBD cancer evolution and need for more sophisticated biological methods of neoplasia risk stratification and detection.

Factors to consider minimizing the development of post-colonoscopy colorectal cancers in inflammatory bowel disease.

Funding

JEE is funded by the National Institute for Health Research [NIHR] Oxford Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Conflict of Interest

JEE has served on the clinical advisory board for Paion; has served on the clinical advisory board and has share options in Satisfai Health; and reports speaker fees from Falk, Jannsen, and Medtronic. AA has received research funding from Olympus.

Author Contributions

All the authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, and/or acquisition, interpretation of the data, revising the article critically for important intellectual content, and approving the final version of the article to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work and MK holds overall responsibility for the content and integrity of the paper.

Ethics

As this was a retrospective audit of standard care formal ethics approval or patient consent was not required.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.