-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rishika Chugh, Manuel B Braga-Neto, Thomas W Fredrick, Guilherme P Ramos, Jonathan Terdiman, Najwa El-Nachef, Edward V Loftus, Uma Mahadevan, Sunanda V Kane, Multicentre Real-world Experience of Upadacitinib in the Treatment of Crohn’s Disease, Journal of Crohn's and Colitis, Volume 17, Issue 4, April 2023, Pages 504–512, https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac157

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Upadacitinib is a selective Janus kinase inhibitor approved for the management of ulcerative colitis and is under evaluation for the management of Crohn’s disease [CD] in Phase 3 clinical trials.

Our goal was to describe our real-world experience with upadacitinib in CD.

This is a two-centre retrospective cohort study of adult patients with moderate to severe CD on upadacitinib. The primary outcome was clinical response and remission as determined by stool frequency and abdominal pain scores. Secondary endpoints included endoscopic response and remission as determined by change in Simple Endoscopic Score for CD. Outcomes were assessed at 3 months after starting upadacitinib and at the patient’s most recent follow-up. We further evaluated adverse events and dose-related response.

A total of 45 CD patients received upadacitinib and were included in the safety analysis. Thirty-six patients received upadacitinib for CD, whereas nine received it for inflammatory arthritis [n = 8] or pyoderma [n = 1]. Thirty-three patients received upadacitinib for 3 months or longer and were included in the efficacy analysis. At the 3-month follow-up, 21 patients achieved clinical response [63.6%] and nine achieved clinical remission [27.2%]. At time of last follow-up, 23 patients had clinical response [69.7%], ten achieved clinical remission [30.3%] and four [28.6%] achieved endoscopic remission. Adverse events occurred in 12 patients [26.7%]. Two patients had a serious adverse event [4.5%] without associated mortality.

In this real-world cohort of highly refractory CD patients, upadacitinib was effective in inducing remission and had an acceptable safety profile.

1. Introduction

The management of moderate to severe Crohn’s disease involves the use of various immune-suppressing medications.1,2 The maintenance therapies for Crohn’s disease fall into four major categories of mechanism of action: anti-tumour necrosis factor [anti-TNF] agents, anti-interleukin [IL] therapies, anti-integrin therapies and immunomodulators, typically used in combination with anti-TNF agents.2 The most recent medication to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration [FDA] for Crohn’s disease was risankizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor approved for use in June 2022.3,4 Despite the advances in recent decades, clinical remission rates among available pharmacological therapies remain sub-optimal, with placebo-adjusted efficacy rates of less than 30–40% and even lower in those with prior TNF exposure.5–7 There remains a significant need for additional and more effective medications. This is especially true for patients with prior medication failures.

Upadacitinib is a selective Janus kinase [JAK] inhibitor approved by the FDA for the management of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, atopic dermatitis and, most recently [March 2022], ulcerative colitis.8–10 Data from available clinical trials have demonstrated favourable efficacy and safety in Crohn’s disease as well.11,12 CELEST, a double-blind placebo-controlled Phase 2 trial of an immediate release formulation of upadacitinib in adults with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease, found that both endoscopic and clinical remission were achieved in a significant proportion of patients compared to placebo at a dose of 24 mg daily and 24 mg twice daily with a safety profile comparable to that of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.13 The Phase 3 U-EXCEED and U-EXCEL induction studies in Crohn’s disease have demonstrated similar outcomes.14,15 After 12 weeks of treatment with upadacitinib 45 mg once daily, 40–51% of Crohn’s disease patients achieved clinical remission and 35–46% achieved endoscopic response.14,15 While these data indicate good efficacy, some studies have demonstrated potential safety concerns. Similar to tofacitinib, a non-selective JAK inhibitor, there may be a risk of venous thromboembolic and acute arterial events.13,16,17 These adverse events were observed in Phase 2 studies for both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.13,16 However, there are few known real-world cases of Crohn’s disease patients on upadacitinib.18,19

The aim of our study was to evaluate the real-world efficacy and safety of off-label upadacitinib in patients with medically refractory Crohn’s disease from tertiary referral centres for inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] in the USA. At these referral centres, the Crohn’s disease patient population includes many who have failed nearly all FDA-approved medications for Crohn’s disease and were therefore not eligible for the clinical trials. Here we describe our real-world experience with upadacitinib in Crohn’s disease, including drug efficacy and safety.

2. Methods

2.1. Data collection

This is a retrospective cohort study of adult patients, age 18 years or older, with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease who received upadacitinib at Mayo Clinic [Minnesota, Florida and Arizona sites] or the University of California San Francisco [UCSF, San Francisco, California] between January 1, 2020 and March 30, 2022. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Mayo Clinic and UCSF. Patients at UCSF were identified through an electronic health record-linked dashboard of all identified IBD patients in the gastroenterology practice. This internal dashboard was queried for all Crohn’s disease patients prescribed upadacitinib. At Mayo Clinic, a bioinformatics search tool was utilized to identify patients with an International Classification of Diseases [ICD] code for Crohn’s disease and the text word ‘upadacitinib’ in their medical records. All data were obtained through retrospective review of the electronic medical record by providers at their respective centres.

2.2. Study population

Patients were included if they had Crohn’s disease based on diagnosis codes and were prescribed upadacitinib for any reason. Patients who were prescribed upadacitinib but did not take or receive the medication for any reason were excluded from the study. Those without the available data to determine drug efficacy or safety in their medical records were excluded. Patients who received upadacitinib but had less than 12 weeks of follow-up at the time of study conclusion were included for safety but not efficacy analysis. However, if a patient had adequate time to complete 12 weeks of upadacitinib at the time of study conclusion but did not remain on the drug or dropped out for any reason, these individuals were included in the efficacy analysis, mirroring an intention-to-treat analysis. Patients who received upadacitinib as part of a clinical trial were excluded. Patient characteristics and baseline disease characteristics were recorded, including baseline endoscopic findings [within 6 months prior to starting upadacitinib] when available, corticosteroid use at the time of upadacitinib initiation, history of IBD-related surgery, the presence of extraintestinal manifestations, baseline serum and stool markers of inflammation [including C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, faecal calprotectin, haemoglobin], and prior biologic or immunomodulator therapy exposure.

2.3. Outcomes

The primary outcomes were clinical response and remission following upadacitinib induction at 3 months and at the patient’s most recent follow-up. Given the retrospective design of this study, outcomes could not be obtained at exactly 3 months. Three-month outcomes were defined as outcomes measured in the 2–5 months following upadacitinib initiation. Last follow-up was defined as the patient’s most recent clinical contact with a healthcare provider. Clinical remission was determined by patient-reported outcomes [PROs] as average daily stool frequency score of ≤1.5 and abdominal pain score of ≤1.0, with neither worse than the baseline value.20 Clinical response was defined as ≥30% reduction from baseline in stool frequency and/or abdominal pain score. Abdominal pain score was graded on a scale of 0–3 with 0 equating to no abdominal pain, 1 to mild pain, 2 to moderate pain and 3 to severe pain. Stool frequency was also graded on a scale of 0–3. A score of 0 correlated with no increased bowel movements from baseline, 1 with one or two bowel movements more than baseline, 2 with three or four bowel movements more than baseline, and 3 with five or more bowel movements compared to baseline.21,22 Secondary endpoints included endoscopic response and remission. Endoscopic remission was defined as Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s disease [SES-CD] of ≤4 and a ≥2-point reduction from baseline, with no sub score >1, and endoscopic response was defined as ≥25% reduction in SES-CD from baseline [similar to the definition used in CELEST].13 Radiographic response and remission were assessed as well. As previously described by Deepak et al., patients were classified as having radiographic response if all lesions stayed the same or some but not all lesions improved. Patients were classified as having radiographic remission at the time of their follow-up imaging if all individual lesions improved. If any of the lesions worsened or a new lesion developed at follow-up imaging, this was classified as a lack of response.23

Additional outcomes evaluated include upadacitinib dosing, adverse events and any possible relationship between the two. Data were gathered on induction [or initial] dosing and maintenance dosing. The induction [or initial] dose was the first dosing formulation the patient received when starting upadacitinib. The maintenance dose was defined as the dose the patient was continued on at the time of the most recent follow-up. All adverse events were recorded including leukopaenia, elevated liver tests, infections [including tuberculosis and herpes zoster specifically], malignancy, intestinal perforation, non-melanoma skin cancer, cardiovascular events, dyslipidaemia, hospitalization and death. Serious adverse events were defined as intestinal perforation, cardiovascular event, hospitalization or death.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Rates of clinical and endoscopic response and remission were calculated. For patient and disease characteristics as well as laboratory findings, mean values with standard deviation were calculated in the setting of normally distributed data whereas median values with an interquartile range [IQR] were calculated in the setting of a skewed data distribution. For all outcomes, a paired analysis was performed. If pre- or post-intervention outcome data were unavailable for any one patient in any specific outcome, the patient was excluded from analysis of that particular outcome. Statistical significance was determined by performing a two-tailed t-test with an alpha of 0.05. Any p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.5. Ethics

Institutional review board approval was obtained at Mayo Clinic [IRB# 21-004995] and UCSF [Study Number: 21-35319] separately.

3. Results

3.1. Patient selection

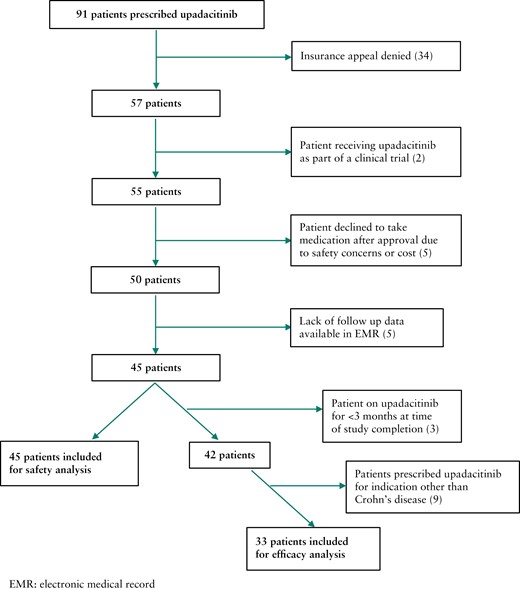

A total of 91 patients with Crohn’s disease were prescribed upadacitinib from all sites. Insurance appeal for upadacitinib was denied for 34 patients [Figure 1]. The denial rate was 43% at Mayo Clinic and 25.8% at UCSF. All denials were due to lack of FDA approval for use of upadacitinib in Crohn’s disease at the time of the prescription. Two patients were receiving upadacitinib as part of a clinical trial and were therefore excluded from analysis. Five patients decided against taking upadacitinib after insurance approval due to concerns regarding safety [n = 4] or cost [n = 1]. Five patients did not have the necessary follow-up data to evaluate for drug safety or clinical response. Of the 45 remaining patients, 42 were prescribed upadacitinib for Crohn’s disease management and nine for another indication. Three patients had not reached the 3-month follow-up mark by the end of the study date and were therefore excluded from the efficacy analysis. Patients who stopped therapy prior to reaching 3 months were included in the safety analysis. Ultimately, 45 patients were included for the safety analysis, and a subset of 33 patients were included for analysis of the primary and secondary outcomes of response and remission [efficacy cohort] [Figure 1].

3.2. Patient population

Of the 45 total patients receiving upadacitinib for any indication, 25 were female [56%] and 35 were identified as non-Hispanic white [78%] [Table 1]. The median age of all patients was 38 years [IQR: 28, 46.5]. Data on body mass index [BMI] were available for 29 of 45 patients. Mean BMI was 27.9 ± 7.2 kg/m2. Most patients [85%] denied any history of tobacco use.

| . | All patients [n = 45] . |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 20 [44%] |

| Female | 25 [56%] |

| Age, years, median [IQR] | 38 [28.0, 46.5] |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD [n = 29] | 27.9 ± 7.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 35 [78%] |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2 [4%] |

| Hispanic | 1 [2%] |

| Asian | 1 [2%] |

| Other | 6 [13%] |

| Smoking status | |

| Former | 5 [11%] |

| Current | 2 [4%] |

| Crohn’s disease | |

| Small bowel only | 4 [9%] |

| Colon only | 7 [16%] |

| Small bowel and colon | 34 [76%] |

| Perianal disease | 24 [53%] |

| Stricturing complications | 31 [69%] |

| Penetrating complications | 27 [60%] |

| Disease duration, years, median [IQR] | 15 [10, 21] |

| Duration on upadacitiniba, days, mean ± SD | 248.3 ± 153.0 |

| Indication for upadacitinib | |

| Crohn’s disease | 36 [80%] |

| Inflammatory arthritis | 8 [18%] |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | 1 [2%] |

| . | All patients [n = 45] . |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 20 [44%] |

| Female | 25 [56%] |

| Age, years, median [IQR] | 38 [28.0, 46.5] |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD [n = 29] | 27.9 ± 7.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 35 [78%] |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2 [4%] |

| Hispanic | 1 [2%] |

| Asian | 1 [2%] |

| Other | 6 [13%] |

| Smoking status | |

| Former | 5 [11%] |

| Current | 2 [4%] |

| Crohn’s disease | |

| Small bowel only | 4 [9%] |

| Colon only | 7 [16%] |

| Small bowel and colon | 34 [76%] |

| Perianal disease | 24 [53%] |

| Stricturing complications | 31 [69%] |

| Penetrating complications | 27 [60%] |

| Disease duration, years, median [IQR] | 15 [10, 21] |

| Duration on upadacitiniba, days, mean ± SD | 248.3 ± 153.0 |

| Indication for upadacitinib | |

| Crohn’s disease | 36 [80%] |

| Inflammatory arthritis | 8 [18%] |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | 1 [2%] |

aPatients were followed until upadacitinib was discontinued.

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index.

| . | All patients [n = 45] . |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 20 [44%] |

| Female | 25 [56%] |

| Age, years, median [IQR] | 38 [28.0, 46.5] |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD [n = 29] | 27.9 ± 7.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 35 [78%] |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2 [4%] |

| Hispanic | 1 [2%] |

| Asian | 1 [2%] |

| Other | 6 [13%] |

| Smoking status | |

| Former | 5 [11%] |

| Current | 2 [4%] |

| Crohn’s disease | |

| Small bowel only | 4 [9%] |

| Colon only | 7 [16%] |

| Small bowel and colon | 34 [76%] |

| Perianal disease | 24 [53%] |

| Stricturing complications | 31 [69%] |

| Penetrating complications | 27 [60%] |

| Disease duration, years, median [IQR] | 15 [10, 21] |

| Duration on upadacitiniba, days, mean ± SD | 248.3 ± 153.0 |

| Indication for upadacitinib | |

| Crohn’s disease | 36 [80%] |

| Inflammatory arthritis | 8 [18%] |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | 1 [2%] |

| . | All patients [n = 45] . |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 20 [44%] |

| Female | 25 [56%] |

| Age, years, median [IQR] | 38 [28.0, 46.5] |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD [n = 29] | 27.9 ± 7.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 35 [78%] |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2 [4%] |

| Hispanic | 1 [2%] |

| Asian | 1 [2%] |

| Other | 6 [13%] |

| Smoking status | |

| Former | 5 [11%] |

| Current | 2 [4%] |

| Crohn’s disease | |

| Small bowel only | 4 [9%] |

| Colon only | 7 [16%] |

| Small bowel and colon | 34 [76%] |

| Perianal disease | 24 [53%] |

| Stricturing complications | 31 [69%] |

| Penetrating complications | 27 [60%] |

| Disease duration, years, median [IQR] | 15 [10, 21] |

| Duration on upadacitiniba, days, mean ± SD | 248.3 ± 153.0 |

| Indication for upadacitinib | |

| Crohn’s disease | 36 [80%] |

| Inflammatory arthritis | 8 [18%] |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | 1 [2%] |

aPatients were followed until upadacitinib was discontinued.

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index.

The median disease duration was 15 years [IQR: 10, 21]. The mean number of days on upadacitinib as of March 30, 2022 was 248.3 ± 153.0. Thirty-four patients had Crohn’s disease involving both the small bowel and colon [76%], seven had colon involvement alone [16%] and four had small bowel involvement alone [9%]. Most patients had complications related to their Crohn’s disease. A history of perianal disease was noted in 24 [53%], penetrating disease characterized by fistula and/or abscess was noted in 27 [60%], and 31 patients had a history of stricturing disease [69%] [Table 1]. Nine patients were prescribed upadacitinib for management of their extra-intestinal manifestations including pyoderma gangrenosum [n = 1] and inflammatory arthritis [n = 8]. In addition to upadacitinib, two of those patients were on ustekinumab and one on vedolizumab in addition to upadacitinib for Crohn’s disease management.

Thirty-six patients were taking upadacitinib for Crohn’s disease management and thirty-three were included in the efficacy cohort [Figure 1]. All patients in the efficacy cohort had previously been on at least one TNF inhibiting agent, vedolizumab and ustekinumab prior to starting upadacitinib [Table 2]. Five patients had been on tofacitinib [15%]. The most commonly prescribed TNF inhibitor was infliximab, and this was previously taken by 97.0% [n = 32] of patients for Crohn’s disease management. Of the 33 patients in the efficacy cohort, 18 [54.5%] had received three different TNF inhibitors prior to starting upadacitinib. Five patients [15%] had previously tried dual biologic therapy for management of their Crohn’s disease. Nineteen patients [57.6%] were on a corticosteroid for IBD management at the time of initiating upadacitinib, and the most common dose and formulation was prednisone 40 mg daily [Table 2]. Thirteen patients underwent colonoscopy to the terminal ileum in the 6 months prior to initiating upadacitinib, and the baseline median SES-CD among this group of patients was 15 [IQR: 10, 26], indicating moderate to severely active disease. In addition, 25 patients [76%] previously had IBD-related surgery including end ileostomy or segmental small bowel resection for stricturing disease, and 14 patients had extra-intestinal manifestations of their disease [42%].

| . | n = 33 . |

|---|---|

| Presence of extra-intestinal manifestations | 14 [42%] |

| History of IBD surgery | 25 [76%] |

| Laboratory parameters, median [IQR] | |

| Faecal calprotectin, µg/g [n = 12] | 598.0 [190.0, 1531.3] |

| hs-CRP, mg/L [n = 24] | 11.0 [2.0, 37.3] |

| ESR, mm/h [n = 14] | 23.5 [9.0, 51.0] |

| Haemoglobin, g/dL [n = 28] | 12.7 [11.4, 13.5] |

| Prior thiopurine or methotrexate use | 33 [97%] |

| Prior biologics use | |

| Prior TNF antagonist use | 33 [100%] |

| One agent | 2 [6.1%] |

| Two agents | 13 [39.4%] |

| Three of more agents | 18 [54.5%] |

| Prior vedolizumab use | 33 [100%] |

| Prior ustekinumab use | 33 [100%] |

| Prior dual biologic or biologic/small molecule use | 5 [15.2%] |

| Prior tofacitinib use | 5 [15.2%] |

| Baseline corticosteroid use with upadacitinib | 19 [57.6%] |

| Baseline median SES-CD score [n = 13] | 15 [10, 26] |

| Follow-up timea, days, median [IQR] | 243 [174, 363.5] |

| . | n = 33 . |

|---|---|

| Presence of extra-intestinal manifestations | 14 [42%] |

| History of IBD surgery | 25 [76%] |

| Laboratory parameters, median [IQR] | |

| Faecal calprotectin, µg/g [n = 12] | 598.0 [190.0, 1531.3] |

| hs-CRP, mg/L [n = 24] | 11.0 [2.0, 37.3] |

| ESR, mm/h [n = 14] | 23.5 [9.0, 51.0] |

| Haemoglobin, g/dL [n = 28] | 12.7 [11.4, 13.5] |

| Prior thiopurine or methotrexate use | 33 [97%] |

| Prior biologics use | |

| Prior TNF antagonist use | 33 [100%] |

| One agent | 2 [6.1%] |

| Two agents | 13 [39.4%] |

| Three of more agents | 18 [54.5%] |

| Prior vedolizumab use | 33 [100%] |

| Prior ustekinumab use | 33 [100%] |

| Prior dual biologic or biologic/small molecule use | 5 [15.2%] |

| Prior tofacitinib use | 5 [15.2%] |

| Baseline corticosteroid use with upadacitinib | 19 [57.6%] |

| Baseline median SES-CD score [n = 13] | 15 [10, 26] |

| Follow-up timea, days, median [IQR] | 243 [174, 363.5] |

aPatients were followed until upadacitinib was discontinued.

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; SES-CD, Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease.

| . | n = 33 . |

|---|---|

| Presence of extra-intestinal manifestations | 14 [42%] |

| History of IBD surgery | 25 [76%] |

| Laboratory parameters, median [IQR] | |

| Faecal calprotectin, µg/g [n = 12] | 598.0 [190.0, 1531.3] |

| hs-CRP, mg/L [n = 24] | 11.0 [2.0, 37.3] |

| ESR, mm/h [n = 14] | 23.5 [9.0, 51.0] |

| Haemoglobin, g/dL [n = 28] | 12.7 [11.4, 13.5] |

| Prior thiopurine or methotrexate use | 33 [97%] |

| Prior biologics use | |

| Prior TNF antagonist use | 33 [100%] |

| One agent | 2 [6.1%] |

| Two agents | 13 [39.4%] |

| Three of more agents | 18 [54.5%] |

| Prior vedolizumab use | 33 [100%] |

| Prior ustekinumab use | 33 [100%] |

| Prior dual biologic or biologic/small molecule use | 5 [15.2%] |

| Prior tofacitinib use | 5 [15.2%] |

| Baseline corticosteroid use with upadacitinib | 19 [57.6%] |

| Baseline median SES-CD score [n = 13] | 15 [10, 26] |

| Follow-up timea, days, median [IQR] | 243 [174, 363.5] |

| . | n = 33 . |

|---|---|

| Presence of extra-intestinal manifestations | 14 [42%] |

| History of IBD surgery | 25 [76%] |

| Laboratory parameters, median [IQR] | |

| Faecal calprotectin, µg/g [n = 12] | 598.0 [190.0, 1531.3] |

| hs-CRP, mg/L [n = 24] | 11.0 [2.0, 37.3] |

| ESR, mm/h [n = 14] | 23.5 [9.0, 51.0] |

| Haemoglobin, g/dL [n = 28] | 12.7 [11.4, 13.5] |

| Prior thiopurine or methotrexate use | 33 [97%] |

| Prior biologics use | |

| Prior TNF antagonist use | 33 [100%] |

| One agent | 2 [6.1%] |

| Two agents | 13 [39.4%] |

| Three of more agents | 18 [54.5%] |

| Prior vedolizumab use | 33 [100%] |

| Prior ustekinumab use | 33 [100%] |

| Prior dual biologic or biologic/small molecule use | 5 [15.2%] |

| Prior tofacitinib use | 5 [15.2%] |

| Baseline corticosteroid use with upadacitinib | 19 [57.6%] |

| Baseline median SES-CD score [n = 13] | 15 [10, 26] |

| Follow-up timea, days, median [IQR] | 243 [174, 363.5] |

aPatients were followed until upadacitinib was discontinued.

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; SES-CD, Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease.

3.3. Upadacitinib dosing

Formulations for initial or induction and maintenance doses were 15 mg daily, 30 mg daily or 45 mg daily [Table 3]. All nine patients receiving upadacitinib for an indication other than Crohn’s disease were started on a dose of 15 mg daily and maintained on either 15 or 30 mg daily.

| All patients . | n = 45 . |

|---|---|

| Induction or initial dose | |

| 15 mg daily | 13 [29%] |

| 30 mg daily | 8 [18%] |

| 45 mg daily | 24 [53%] |

| Maintenance dose | |

| 15 mg daily | 13 [29%] |

| 30 mg daily | 14 [31%] |

| 45 mg daily | 18 [40%] |

| All patients . | n = 45 . |

|---|---|

| Induction or initial dose | |

| 15 mg daily | 13 [29%] |

| 30 mg daily | 8 [18%] |

| 45 mg daily | 24 [53%] |

| Maintenance dose | |

| 15 mg daily | 13 [29%] |

| 30 mg daily | 14 [31%] |

| 45 mg daily | 18 [40%] |

| Efficacy cohort . | n = 33 . |

|---|---|

| Induction or initial dose | |

| 15 mg daily | 4 [12%] |

| 30 mg daily | 8 [24%] |

| 45 mg daily | 21 [64%] |

| Maintenance dose | |

| 15 mg daily | 6 [18%] |

| 30 mg daily | 12 [36%] |

| 45 mg daily | 15 [45%] |

| Duration on 45 mg dose in all patients | |

| Median [IQR] in days | 114 [90, 212] |

| Median [IQR] in months | 3.8 [3.0, 7.1] |

| Efficacy cohort . | n = 33 . |

|---|---|

| Induction or initial dose | |

| 15 mg daily | 4 [12%] |

| 30 mg daily | 8 [24%] |

| 45 mg daily | 21 [64%] |

| Maintenance dose | |

| 15 mg daily | 6 [18%] |

| 30 mg daily | 12 [36%] |

| 45 mg daily | 15 [45%] |

| Duration on 45 mg dose in all patients | |

| Median [IQR] in days | 114 [90, 212] |

| Median [IQR] in months | 3.8 [3.0, 7.1] |

IQR, interquartile range.

| All patients . | n = 45 . |

|---|---|

| Induction or initial dose | |

| 15 mg daily | 13 [29%] |

| 30 mg daily | 8 [18%] |

| 45 mg daily | 24 [53%] |

| Maintenance dose | |

| 15 mg daily | 13 [29%] |

| 30 mg daily | 14 [31%] |

| 45 mg daily | 18 [40%] |

| All patients . | n = 45 . |

|---|---|

| Induction or initial dose | |

| 15 mg daily | 13 [29%] |

| 30 mg daily | 8 [18%] |

| 45 mg daily | 24 [53%] |

| Maintenance dose | |

| 15 mg daily | 13 [29%] |

| 30 mg daily | 14 [31%] |

| 45 mg daily | 18 [40%] |

| Efficacy cohort . | n = 33 . |

|---|---|

| Induction or initial dose | |

| 15 mg daily | 4 [12%] |

| 30 mg daily | 8 [24%] |

| 45 mg daily | 21 [64%] |

| Maintenance dose | |

| 15 mg daily | 6 [18%] |

| 30 mg daily | 12 [36%] |

| 45 mg daily | 15 [45%] |

| Duration on 45 mg dose in all patients | |

| Median [IQR] in days | 114 [90, 212] |

| Median [IQR] in months | 3.8 [3.0, 7.1] |

| Efficacy cohort . | n = 33 . |

|---|---|

| Induction or initial dose | |

| 15 mg daily | 4 [12%] |

| 30 mg daily | 8 [24%] |

| 45 mg daily | 21 [64%] |

| Maintenance dose | |

| 15 mg daily | 6 [18%] |

| 30 mg daily | 12 [36%] |

| 45 mg daily | 15 [45%] |

| Duration on 45 mg dose in all patients | |

| Median [IQR] in days | 114 [90, 212] |

| Median [IQR] in months | 3.8 [3.0, 7.1] |

IQR, interquartile range.

The most common induction dose was 45 mg daily, taken by 21 patients in the efficacy cohort [64%]. In some situations, the patient was initially prescribed 45 mg daily for induction, but this dose was denied by insurance due to lack of FDA approval and therefore 30 or 15 mg daily was started instead. Eight patients [24%] received an induction dose of 30 mg daily and four [12%] received an induction dose of 15 mg daily. The most commonly prescribed maintenance dose in this cohort was also 45 mg daily, taken by 15 patients [45%]. One of these patients had his dose later decreased from 45 mg daily to 30 mg daily for maintenance due to leukopaenia presumed to be secondary to upadacitinib with subsequent resolution of leukopaenia. One patient had her dose decreased to 30 mg daily after 10 months of treatment with 45 mg daily but subsequently had a flare of her disease; her dose was increased back to 45 mg daily thereafter but the previous clinical response was not recaptured. A third patient on 45 mg daily for maintenance was initially started on 30 mg daily but later increased to 45 mg daily in conjunction with rheumatology to relieve pain from inflammatory arthritis. Among those patients receiving upadacitinib 45 mg daily, the median duration on this dose was 114 days [IQR: 90, 212].

3.4. Response and remission

Thirty-three patients received upadacitinib for Crohn’s disease management and had available data on clinical response. At 3 months, 21 patients [63.6%, p < 0.001] had clinical response and nine patients [27.3%, p = 0.002] had achieved clinical remission as determined by improvements in their stool frequency and abdominal pain scores [Figure 2A, Table 4]. At the last follow-up, 23 patients [69.7%, p < 0.001] had clinical response and ten had achieved clinical remission [30.3%, p < 0.001]. Stool frequency scores decreased over time, starting at a median of 3 at baseline and 1 at last follow-up [p < 0.001] [Table 4]. Abdominal pain scores also decreased over time, starting at a median of 2 at baseline and 1 at last follow-up [p < 0.001]. Comparative data on endoscopic outcomes were available for 14 patients in the efficacy cohort. At 6 months, eight patients [57.1% of those with available comparative data, p = 0.08] had evidence of endoscopic response as determined by change in SES-CD scores and four [28.6%, p = 0.003] were in endoscopic remission [Table 4]. Comparative radiographic data in the form of magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] or computerized tomography [CT] were available in 12 patients, with radiographic response achieved in two [16.7%, p = 0.17] and remission in one [8.3%, p = 0.34] [Table 4]. CT and MRI were the only two modes of imaging utilized in our patients to assess response and remission. At 3 months, 11 patients [33.3%, p = 0.01] continued to take corticosteroids. At the most recent follow-up, 13 patients [39.4%, p = 0.06] were on steroids, compared to 19 [57.6%] at baseline [Table 4]. Two patients required new initiation of steroids due to worsening gastrointestinal symptoms attributed to a lack of response to upadacitinib. Notably, of the five patients who had previously received and failed another JAK inhibitor, tofacitinib, off-label for Crohn’s management, three of them achieved clinical response but none achieved clinical remission on upadacitinib. Rates of clinical response and remission as related to upadacitinib dosing were calculated as well. Rates of clinical remission and response with induction doses of 30 and 45 mg were higher than those with 15 mg [Figure 2B and C]. The maintenance dose of 30 mg had higher rates of clinical remission and response at both 3 months and last follow-up.

| . | Pre-treatment . | At 3 months . | p-valuea . | At last follow-up . | p-valuea . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical remission [n = 33] | 9 [27.3%] | 0.002 | 10 [30.3%] | <0.001 | |

| Clinical response [n = 33] | 21 [63.6%] | <0.001 | 23 [69.7%] | <0.001 | |

| Abdominal pain score, median [n = 33] | 2 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Stool frequency score, median [n = 33] | 3 | 2 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Corticosteroid use [n = 33] | 19 [57.6%] | 11 [33.3%] | 0.01 | 13 [39.4%] | 0.06 |

| Laboratory markers, median [Q1, Q3] | |||||

| Faecal calprotectin, µg/g | 138.5 [66.7, 386.5] n = 8 | 0.18 | 204 [27.5, 1072.5] n = 9 | 0.48 | |

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 3.1 [1.4, 18.2] n = 18 | 0.03 | 4 [0.5, 31.6] n = 20 | 0.30 | |

| ESR, mm/h | 11 [5.3, 15.8] n = 11 | 0.02 | 20.5 [6, 36.8] n = 12 | 0.32 | |

| Haemoglobin, g/dL | 11.9 [11.5, 13.1] n = 24 | 0.32 | 12.2 [11.5, 13.5] n = 26 | 0.32 | |

| Endoscopic remission [n = 14] | 4 [28.6%] | 0.003 | |||

| Endoscopic response [n = 14] | 8 [57.1%] | 0.08 | |||

| Imaging remission [n = 12] | 1 [8.3%] | 0.34 | |||

| Imaging response [n = 12] | 2 [16.7%] | 0.17 | |||

| . | Pre-treatment . | At 3 months . | p-valuea . | At last follow-up . | p-valuea . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical remission [n = 33] | 9 [27.3%] | 0.002 | 10 [30.3%] | <0.001 | |

| Clinical response [n = 33] | 21 [63.6%] | <0.001 | 23 [69.7%] | <0.001 | |

| Abdominal pain score, median [n = 33] | 2 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Stool frequency score, median [n = 33] | 3 | 2 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Corticosteroid use [n = 33] | 19 [57.6%] | 11 [33.3%] | 0.01 | 13 [39.4%] | 0.06 |

| Laboratory markers, median [Q1, Q3] | |||||

| Faecal calprotectin, µg/g | 138.5 [66.7, 386.5] n = 8 | 0.18 | 204 [27.5, 1072.5] n = 9 | 0.48 | |

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 3.1 [1.4, 18.2] n = 18 | 0.03 | 4 [0.5, 31.6] n = 20 | 0.30 | |

| ESR, mm/h | 11 [5.3, 15.8] n = 11 | 0.02 | 20.5 [6, 36.8] n = 12 | 0.32 | |

| Haemoglobin, g/dL | 11.9 [11.5, 13.1] n = 24 | 0.32 | 12.2 [11.5, 13.5] n = 26 | 0.32 | |

| Endoscopic remission [n = 14] | 4 [28.6%] | 0.003 | |||

| Endoscopic response [n = 14] | 8 [57.1%] | 0.08 | |||

| Imaging remission [n = 12] | 1 [8.3%] | 0.34 | |||

| Imaging response [n = 12] | 2 [16.7%] | 0.17 | |||

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

ap-values were determined against the pre-treatment values. Pre-treatment, no patients were in clinical remission or had a clinical response.

| . | Pre-treatment . | At 3 months . | p-valuea . | At last follow-up . | p-valuea . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical remission [n = 33] | 9 [27.3%] | 0.002 | 10 [30.3%] | <0.001 | |

| Clinical response [n = 33] | 21 [63.6%] | <0.001 | 23 [69.7%] | <0.001 | |

| Abdominal pain score, median [n = 33] | 2 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Stool frequency score, median [n = 33] | 3 | 2 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Corticosteroid use [n = 33] | 19 [57.6%] | 11 [33.3%] | 0.01 | 13 [39.4%] | 0.06 |

| Laboratory markers, median [Q1, Q3] | |||||

| Faecal calprotectin, µg/g | 138.5 [66.7, 386.5] n = 8 | 0.18 | 204 [27.5, 1072.5] n = 9 | 0.48 | |

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 3.1 [1.4, 18.2] n = 18 | 0.03 | 4 [0.5, 31.6] n = 20 | 0.30 | |

| ESR, mm/h | 11 [5.3, 15.8] n = 11 | 0.02 | 20.5 [6, 36.8] n = 12 | 0.32 | |

| Haemoglobin, g/dL | 11.9 [11.5, 13.1] n = 24 | 0.32 | 12.2 [11.5, 13.5] n = 26 | 0.32 | |

| Endoscopic remission [n = 14] | 4 [28.6%] | 0.003 | |||

| Endoscopic response [n = 14] | 8 [57.1%] | 0.08 | |||

| Imaging remission [n = 12] | 1 [8.3%] | 0.34 | |||

| Imaging response [n = 12] | 2 [16.7%] | 0.17 | |||

| . | Pre-treatment . | At 3 months . | p-valuea . | At last follow-up . | p-valuea . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical remission [n = 33] | 9 [27.3%] | 0.002 | 10 [30.3%] | <0.001 | |

| Clinical response [n = 33] | 21 [63.6%] | <0.001 | 23 [69.7%] | <0.001 | |

| Abdominal pain score, median [n = 33] | 2 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Stool frequency score, median [n = 33] | 3 | 2 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Corticosteroid use [n = 33] | 19 [57.6%] | 11 [33.3%] | 0.01 | 13 [39.4%] | 0.06 |

| Laboratory markers, median [Q1, Q3] | |||||

| Faecal calprotectin, µg/g | 138.5 [66.7, 386.5] n = 8 | 0.18 | 204 [27.5, 1072.5] n = 9 | 0.48 | |

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 3.1 [1.4, 18.2] n = 18 | 0.03 | 4 [0.5, 31.6] n = 20 | 0.30 | |

| ESR, mm/h | 11 [5.3, 15.8] n = 11 | 0.02 | 20.5 [6, 36.8] n = 12 | 0.32 | |

| Haemoglobin, g/dL | 11.9 [11.5, 13.1] n = 24 | 0.32 | 12.2 [11.5, 13.5] n = 26 | 0.32 | |

| Endoscopic remission [n = 14] | 4 [28.6%] | 0.003 | |||

| Endoscopic response [n = 14] | 8 [57.1%] | 0.08 | |||

| Imaging remission [n = 12] | 1 [8.3%] | 0.34 | |||

| Imaging response [n = 12] | 2 [16.7%] | 0.17 | |||

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

ap-values were determined against the pre-treatment values. Pre-treatment, no patients were in clinical remission or had a clinical response.

![Clinical outcomes. [A] Overall rates of clinical outcomes at 3 months and last follow-up. [B] Dose-dependent clinical outcomes with varying induction doses. [C] Clinical outcomes with varying maintenance doses.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ecco-jcc/17/4/10.1093_ecco-jcc_jjac157/1/m_jjac157_fig2.jpeg?Expires=1749029814&Signature=3PpIWGxK5NHTFn0mFPp3x3t3l0q7B4XUDWcd4LgJcS1KDeuH8w0KO3vVXnaJOequWIKL40zJfBi5fyxMvBm7iPfuHF1wBOOvJl0P2Q07UqyuA9bfa08EmMMI7b4UTC~SwfFBFqGvw1nlWGAyayAJdtLXlYUbr-P~66gcZYOPS5q~3lFmBbmc-fwuthoft5y1ftBbWpMtYgGU~x3yWN4GnH~WoKhCwOwotZ57dV3afyN5J1v6DWZPlS07vdi4dkcAKyoCnLfN-FOvwzqYb-ufol2t5mJ8GF4T9ihFYXdZgs0DGHl4urT9ccLVGoeL61WMogMTSLx8MSHeL26r30aRqg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Clinical outcomes. [A] Overall rates of clinical outcomes at 3 months and last follow-up. [B] Dose-dependent clinical outcomes with varying induction doses. [C] Clinical outcomes with varying maintenance doses.

Two patients had loss of response after 3 months. Both patients responded adequately to the induction dose of 45 mg of upadacitinib and had loss of response when the dose was decreased to 30 mg. Response was recaptured after the dose of upadacitinib was escalated back to 45 mg.

3.5. Stool and serum markers

Stool and serum markers of inflammation were evaluated at baseline, at 3 months and at last follow-up. Comparative faecal calprotectin values were available for eight patients at the 3-month follow-up and for nine patients at last follow-up. At 3 months, faecal calprotectin was a median of 138.5 μg/g [IQR: 66.7, 386.5] compared to a baseline of 347.5 µg/g [IQR: 100.5, 2136.5] with a difference of 209 µg/g [p = 0.18] [Table 4]. The median value remained low at most recent follow-up and was decreased from baseline by 302 µg/g [p = 0.48]. Comparative high sensitivity C-reactive protein [hs-CRP] was available for 18 patients at 3 months follow-up and 20 patients at most recent follow-up. There was a statistically significant decrease in median hs-CRP by 11.8 mg/L [p = 0.03] from baseline to 3 months and a decrease by 6.85 mg/L [p = 0.30] from baseline to most recent follow-up. Comparative erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] values were available for 11 patients at 3 months of follow-up and 12 patients at last follow-up. There was a decrease in median ESR values from baseline by 24 mm/h [p = 0.02] at 3 months and by 9 mm/h [p = 0.32] at last follow-up. Comparative haemoglobin values were available for 24 patients at 3 months and 26 patients at last follow-up. Haemoglobin values decreased at 3 months by 0.6 g/dL [p = 0.32] for a median of 11.9 g/dL [IQR: 11.4, 13.0] and by 0.4 g/dL [p = 0.32] at last follow-up for a median of 12.2 g/dL [IQR: 11.3, 13.1] [Table 4].

3.6. Drug safety

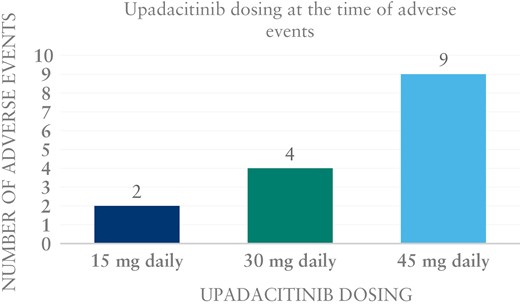

All 45 patients were included for drug safety analysis. Fifteen adverse events [AEs] occurred in 12 patients [27%] [Table 5] and [Figure 3]. Two [4.4%] had a serious AE. One of the serious AEs was a deep vein thrombus [DVT] in one patient [a 48-year-old male]; this occurred while he was receiving upadacitinib 45 mg daily for maintenance. This patient had a lower extremity Doppler ultrasound as part of pre-surgical evaluation for his varicose veins, which incidentally revealed a non-occlusive chronic thrombus in the right lower extremity. Given that the thrombus was described radiographically to be chronic rather than acute, there was a suspicion that it occurred in the setting of IBD flare prior to starting upadacitinib as opposed to following its initiation. No other risk factors for a thrombotic event were found, and disease was in remission at the time the DVT was noted. The second serious AE was hospitalization for an intra-abdominal abscess. While the patient was hospitalized in the setting of taking upadacitinib, this infection was thought to have developed due to complications surrounding a recent abdominal hernia repair. This was the only infectious complication potentially related to upadacitinib seen among all 45 patients. There were no episodes of herpes zoster infection or tuberculosis. No deaths occurred.

| Event . | Patients [n = 45] . |

|---|---|

| Total number of AEs | 15 |

| Total number of unique patients with AEs | 12 [27%] |

| Dyslipidaemia | 3 [7%] |

| Leukopaenia | 1 [2%] |

| Elevated liver tests | 3 [7%] |

| Malignancy | 0 [0%] |

| Infection | |

| All infectious complications | 1 [3%] |

| Zoster infection | 0 [0%] |

| Tuberculosis and other opportunistic infection | 0 [0%] |

| Other non-serious adverse events | 5 [11%] |

| Serious adverse events | |

| Cardiovascular event | 1 [3%] |

| Hospitalization | 1 [3%] |

| Intestinal perforation | 0 [0%] |

| Mortality | 0 [0%] |

| Event . | Patients [n = 45] . |

|---|---|

| Total number of AEs | 15 |

| Total number of unique patients with AEs | 12 [27%] |

| Dyslipidaemia | 3 [7%] |

| Leukopaenia | 1 [2%] |

| Elevated liver tests | 3 [7%] |

| Malignancy | 0 [0%] |

| Infection | |

| All infectious complications | 1 [3%] |

| Zoster infection | 0 [0%] |

| Tuberculosis and other opportunistic infection | 0 [0%] |

| Other non-serious adverse events | 5 [11%] |

| Serious adverse events | |

| Cardiovascular event | 1 [3%] |

| Hospitalization | 1 [3%] |

| Intestinal perforation | 0 [0%] |

| Mortality | 0 [0%] |

AEs, adverse events.

| Event . | Patients [n = 45] . |

|---|---|

| Total number of AEs | 15 |

| Total number of unique patients with AEs | 12 [27%] |

| Dyslipidaemia | 3 [7%] |

| Leukopaenia | 1 [2%] |

| Elevated liver tests | 3 [7%] |

| Malignancy | 0 [0%] |

| Infection | |

| All infectious complications | 1 [3%] |

| Zoster infection | 0 [0%] |

| Tuberculosis and other opportunistic infection | 0 [0%] |

| Other non-serious adverse events | 5 [11%] |

| Serious adverse events | |

| Cardiovascular event | 1 [3%] |

| Hospitalization | 1 [3%] |

| Intestinal perforation | 0 [0%] |

| Mortality | 0 [0%] |

| Event . | Patients [n = 45] . |

|---|---|

| Total number of AEs | 15 |

| Total number of unique patients with AEs | 12 [27%] |

| Dyslipidaemia | 3 [7%] |

| Leukopaenia | 1 [2%] |

| Elevated liver tests | 3 [7%] |

| Malignancy | 0 [0%] |

| Infection | |

| All infectious complications | 1 [3%] |

| Zoster infection | 0 [0%] |

| Tuberculosis and other opportunistic infection | 0 [0%] |

| Other non-serious adverse events | 5 [11%] |

| Serious adverse events | |

| Cardiovascular event | 1 [3%] |

| Hospitalization | 1 [3%] |

| Intestinal perforation | 0 [0%] |

| Mortality | 0 [0%] |

AEs, adverse events.

There were 13 non-serious AEs. One patient developed mild leukopaenia with absolute neutrophil count of 1300. The dose of upadacitinib was decreased from 45 to 30 mg daily, and the leukopaenia resolved. Three patients [6.6%] had elevated liver tests. Two were receiving 45 mg daily of upadacitinib at the time, one for maintenance and one for induction. The third patient was on upadacitinib 30 mg daily. Three patients developed dyslipidaemia [6.6%]. Two of them were on a dose of 45 mg daily and one was on 15 mg daily. Notably, dyslipidaemia was not specifically assessed in approximately half of our patient population. Other non-serious AEs were headaches, myalgias, nausea and vomiting, and abdominal pain. One patient had pustular psoriasis with unclear relationship to upadacitinib.

4. Discussion

We describe off-label experience with upadacitinib in a highly refractory Crohn’s disease population from tertiary centres. After 12 weeks of treatment, clinical remission was achieved in 27.3% [p = .002] of patients, while clinical response was achieved in 63.6% [p < 0.001] of patients. At time of last follow-up, similar clinical response and remission rates were found compared to at 3 months, while endoscopic remission was achieved in 28.6% [p = 0.08] of patients with comparative pre- and post-treatment data [n = 14]. Serious AEs, including DVT and one hospitalization secondary to infection, occurred in two patients [4.4%] without associated mortality. Notably, there was suspicion that both of these events did not occur due to upadacitinib itself but rather other pre-existing conditions. Overall, we demonstrate favourable real-world efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in a highly refractory cohort of Crohn’s disease patients that had previously failed anti-TNF, anti-integrin and anti-IL12/23 biologics.

The efficacy of upadacitinib was initially evaluated in the CELEST study, a multicentre randomized Phase 2 trial involving 220 patients, using an immediate release formulation.13 During the induction period, the dose of 24 mg twice daily demonstrated best results and 22% of patients in that group achieved clinical and endoscopic remission, while up to 38% of patients achieved endoscopic remission in the maintenance period. Most recently, two ongoing Phase 3 clinical trials, U-EXCEED and U-EXCEL,14,15 have preliminarily reported and confirmed the significant efficacy of upadacitinib with clinical remission rates of 39 and 49%, respectively, during the induction period. In our cohort, we found a numerically lower rate of clinical response of 27% in the induction period. This is probably secondary to our highly refractory patient population, where 100% of patients had previously been on a TNF-antagonist and non-TNF antagonist, whereas in the CELEST trial ~40% had prior non-TNF antagonist exposure. In addition, in our cohort, only 64% of patients received the induction dose of 45 mg upadacitinib.

To date, only two small case series of off-label upadacitinib in Crohn’s disease have been published.18,19 In a case series from Germany including six patients, reduction in calprotectin was seen in all patients; however, clinical data were available in only four patients, and data beyond 12 weeks of follow-up were not available.18 Most recently, a single-centre case series including 12 patients reported a clinical response rate of 25%.19

During the maintenance period of the CELEST trial, at 52 weeks, patients on upadacitinib 12 mg twice daily achieved the highest rates of clinical and endoscopic remission, at up to 63 and 38%, respectively.13 A recent update from the CELEST trial data confirmed long-term efficacy and safety of upadacitinib.24 We found that at the time of last follow-up, 30.3% [p < 0.001] were in clinical remission while 57.1% [out of those with available comparative data, p = 0.08] achieved endoscopic remission. In agreement, biomarker levels, including faecal calprotectin and CRP, were decreased compared to baseline at time of last follow-up. In our cohort, the mean follow-up time was ~40 weeks. The numerically lower rates of clinical remission and endoscopic remission may be due to a combination of a highly refractory patient population and that nearly one-third of patients were on the lowest dose, 15 mg daily, for maintenance, commonly dictated by insurance.

JAK inhibitors, particularly non-selective inhibitors, have been previously associated with significant AEs.25 Tofacitinib is an FDA-approved medication for ulcerative colitis; however, it is only approved in patients who have previously failed anti-TNF therapy, mostly due to concern over safety data including cardiovascular events such as thromboembolism and stroke.26 Upadacitinib was very recently also approved by the FDA for the treatment of ulcerative colitis, and the available safety data appear to be more favourable.16 Most of the safety data from both tofacitinib and upadacitinib derive from rheumatology trials, which somewhat limits the data interpretation. In Crohn’s disease, safety data from the CELEST trial demonstrated serious AEs occurred in up to 27.8% of patients, more frequently see in the higher doses tested. In our cohort, AEs were reported in 27% of our patients, with only two patients developing serious AEs including DVT and intra-abdominal infection requiring hospitalization.13 Interestingly, most AEs occurred in the group of patients on 45 mg upadacitinib.

Our study has several limitations including retrospective study design, heterogeneity of upadacitinib dose and follow-up, including availability of endoscopic data in only a subset of patients. The small sample size of this study is a limitation and our efficacy analysis results should be interpreted with caution given lack of adequate power. Moreover, while we attempted to evaluate for radiographic response, there are no standardized methods by which to assess for endoscopic response or remission as radiology readings were variable. Quantitative data such as bowel wall thickness were not available for all patients. Strengths of our study include novelty, and inclusion of patients from multiple IBD centres and a highly refractory group of patients. While clinical trials had approximately one-third failing at least three biologics, we had 100% of patients failing at least three biologics with at least three different mechanisms of action.

In conclusion, we demonstrate in a real-world cohort that upadacitinib is effective in inducing remission in a highly refractory Crohn’s disease patient population with acceptable safety profile.

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

RC, MB, TF, GR: none. JT: Research support: Abbvie. NE: Research support: Finch Therapeutics, Seres, Assembly Biosciences and Freenome; Consultant: Ferring Pharmaceuticals and Federation Bio. EVL: Consulting for AbbVie, Amgen, Arena, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CALIBR, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Gilead, Gossamer Bio, Iterative Scopes, Janssen, Morphic, Ono, Pfizer, Protagonist, Scipher Medicine, Sun, Surrozen, Takeda, and UCB; research support from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene/Receptos, Genentech, Gilead, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, Theravance and UCB. Shareholder, Exact Sciences. UM: Consultant: Abbvie, Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Takeda, Pfizer, Lilly, Gilead, Arena; Prometheus Biosciences, Protagonist, Surrozen, Boehringer Ingelheim. SK: Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Janssen, Gilead, InveniAI, PredictaMed, Seres Therapeutics, Spherix Health, Takeda, TechLab, United Healthcare, UptoDate.

Author Contributions

RC and MB: acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation and drafting of the manuscript; TF: acquisition of data; GR, JT and NE: critical review for important intellectual content; EVL, UM and SK: interpretation of data, study design and critical review.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Author notes

Chugh and Braga-Neto. These authors contributed equally to this work.

Mahadevan and Kane. Co-senior authors.