-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Esther Ventress, David Young, Sohail Rahmany, Clare Harris, Marion Bettey, Trevor Smith, Helen Moyses, Magdalena Lech, Markus Gwiggner, Richard Felwick, J R Fraser Cummings, Transitioning from Intravenous to Subcutaneous Vedolizumab in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease [TRAVELESS], Journal of Crohn's and Colitis, Volume 16, Issue 6, June 2022, Pages 911–921, https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab224

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

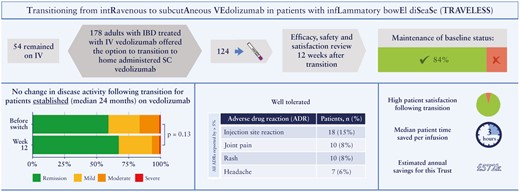

Subcutaneous [SC] vedolizumab presents the opportunity for inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] patients to manage their treatment at home. There are currently no data on the process of transitioning patients established on intravenous [IV] to SC vedolizumab as part of routine clinical care. The aim of this programme is to evaluate the clinical and biochemical outcomes of switching a cohort of IBD patients established on IV vedolizumab to SC, at 12 weeks following the transition.

In all, 178 adult patients were offered the opportunity to transition to SC vedolizumab. Patients who agreed were reviewed prior to switching and at Week 12 [W12] after their first SC dose. Evaluation outcomes included disease activity scores, the IBD-Control Patient-Reported Outcome Measures [PROMs], and faecal calprotectin [FCP]. Reasons for patients declining or accepting transitioning, pharmacokinetics, adverse drug reactions, and risk factors for a poor outcome in SARS-CoV-2 infection were also assessed.

A total of 124 patients agreed to transition, of whom 106 patients had been on IV vedolizumab for at least 4 months. There were no statistically significant differences in disease activity scores or IBD-Control PROMs between baseline and W12. A statistically significant increase in FCP was observed [31 µg/g vs. 47 µg/g; p = 0.008], although this was unlikely to be clinically relevant. The most common adverse drug reaction reported was injection site reactions [15%]. Based on this cohort of patients, an expected reduction of £572,000 per annum is likely to be achieved.

Transitioning patients established on IV vedolizumab to SC appears to be safe and effective, with high patient satisfaction and multiple benefits for the health service.

1. Introduction

Crohn’s disease [CD], ulcerative colitis [UC], and inflammatory bowel disease-unclassified [IBD-U] are immune-mediated chronic inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract which can result in progressive damage and associated loss of function and disability. Patients often require long-term treatment to achieve and maintain clinical remission with a resultant improvement in quality of life. Vedolizumab, a humanised monoclonal antibody, binds to α 4β 7 integrin on gut-homing T helper lymphocytes. This blocks the adhesion of T helper lymphocytes to mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 [MAdCAM-1] expressed on endothelial cells in the gut, thereby reducing the migration of these cells into gastrointestinal tissues.1 Emerging evidence suggests that vedolizumab also has effects on innate immunity through alterations in macrophage populations and microbial sensing processes.2 In 2015, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] recommended intravenous [IV] vedolizumab for the treatment of moderately to severely active CD and UC in patients who are unable to tolerate or who have not responded to conventional therapy, including thiopurines, methotrexate, and corticosteroids, or anti-tumour necrosis factor [TNF] drugs.3,4

There are a number of potential advantages for patients in using subcutaneous [SC] versus IV therapies, including the convenience of not having to travel to infusion centres, saving time and travel expenses, and reducing time away from education or work. There may also be benefit for patients being able to manage their treatment more independently at home. In the absence of data, during the COVID-19 pandemic there was concern for patients that coming to hospital for infusions with known risk factors for a poor outcome from SARS-CoV-2 infection5,6 could increase their risk of infection. SC therapy was an opportunity to reduce attendance at infusion centres, the risk of hospital-acquired infections, and travel-related COVID-19 exposure.

The NHS Long Term Plan aims to increase capacity for patients to be able to receive medical care at home.7 Advantages to health care providers of switching patients to SC therapies include potential cost savings and freeing up capacity within infusion centres for other IV therapies. The drug acquisition costs of SC vedolizumab administered every 2 weeks [Q2W] are similar to the cost of the IV infusions administered every 8 weeks [Q8W]. There is a potential for further cost savings in patients who are on infusions more frequently than Q8W.

There are a number of reasons that patients may not prefer SC administration, including a reluctance to self-inject and concerns of reduced contact with health care professionals by not attending infusion centres.8–10 A multicentre survey of IBD patients, which explored preference for IV or SC administration, found that older age and higher education were predictors for having a preference for SC.11 However, the most notable predictor for SC or IV preference was previous experience with either mode of administration.

The VISIBLE 1 and VISIBLE 2 phase III clinical trials showed that SC vedolizumab was effective as maintenance therapy in patients who had a clinical response to IV vedolizumab induction therapy with moderately to severely active UC and CD, respectively. The primary endpoint was met in both trials, demonstrating that the proportion of patients achieving clinical remission at Week 52 was significantly greater with SC vedolizumab versus placebo.12,13 In VISIBLE 1, the secondary endpoint of endoscopic improvement [a Mayo endoscopic sub-score of 1 or less] was significantly higher in patients on SC vedolizumab versus placebo, but there was a non-significant increase in the number of patients who achieved corticosteroid-free remission. There were no new safety concerns and no significant differences in adverse events between SC and IV administration, with the exception of injection site reactions with SC. Median serum trough levels of vedolizumab at steady state dosing were higher with SC than for IV. For both IV and SC administration of vedolizumab, higher serum levels correlated with a higher proportion of patients achieving clinical remission and endoscopic improvement.12 VISIBLE 2 demonstrated similar safety outcomes in patients with CD, although there was not a comparator IV maintenance arm.13 There were significant improvements in the secondary endpoints, enhanced clinical response and corticosteroid-free clinical remission at Week 52, in patients treated with SC vedolizumab compared with placebo. In May 2020, SC vedolizumab was licensed for maintenance therapy in IBD after at least two IV infusions.14

The VISIBLE studies demonstrated the efficacy of SC vedolizumab in patients newly starting treatment. However, the majority of patients treated with vedolizumab have been established on treatment, and the VISIBLE programme did not address the outcomes of transitioning to SC administration in this real-world patient group. The aim of this project is to evaluate the outcomes of transitioning a cohort of IBD patients receiving IV vedolizumab as standard of care at a large IBD centre to SC, using validated disease activity scores, patient reported outcomes, and laboratory measures. Reasons for patients declining SC, pharmacokinetics, adverse drug reactions, and the presence of risk factors which may predict a poor outcome in SARS-CoV-2 infection will also be assessed.

2. Methods

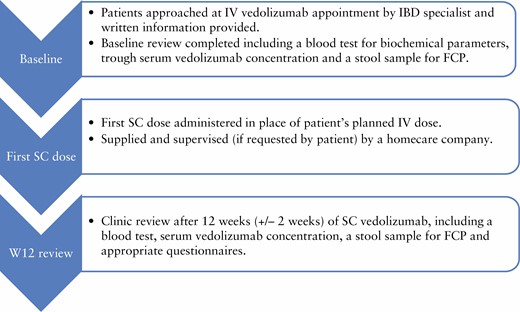

2.1. Transitioning programme design

The transitioning programme is described in Figure 1. Patients over the age of 18, who were either established on IV vedolizumab or had newly started and opted for SC administration after two IV loading doses, were approached between October and December 2020 to take part in a service evaluation at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust [registered with the Trust’s governance team: reference SEV/0282]. Patients previously known to have difficulties with compliance were excluded [n = 2]. Patients were sent a letter with information regarding transitioning to SC [Supplementary Figure 1, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online] and a request to submit a stool sample to assess faecal calprotectin [FCP] at their next infusion appointment. Concomitant medications were continued throughout the transition as per routine clinical management.

Initially, the aim was to offer a SC dose to patients in place of their IV infusion, with injection training by an IBD specialist pharmacist, IBD specialist nurse, or clinical research fellow. This proved to be a challenge, as it left a narrow time window for homecare deliveries to be arranged for subsequent doses. The remaining patients [n = 81] who agreed to the transition received an IV infusion at their baseline review, as well as SC injection training using demonstration prefilled pens and syringes, with the aim of self-administering their first SC dose in place of the next scheduled IV dose at home. There were 32 patients [40%] who accepted the offer of nursing support when administering their first dose at home. At their baseline visit, all patients were provided with further written information [Supplementary Figure 2, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online] and counselling on dosing, storage requirements, information on the homecare company delivering the vedolizumab, and how to contact the IBD team for support. Patients were given blood forms for routine monitoring and a stool sample pot for a FCP sample. At Week 12 [W12] after commencement of SC vedolizumab, patients had a single clinic review as part of their routine care at dedicated transitioning clinics. There was no additional follow-up for patients who declined to transition beyond standard of care.

2.2. Assessment of outcomes

The outcomes of the service evaluation include reasons for consenting or declining to transition, time saved by not needing to travel to the infusion centre, and patient experience with using SC injections. Risk factors associated with poor outcomes from SARS-CoV-2 infection were collected, including comorbidities, smoking status, concomitant medication, and age, based on the British Society of Gastroenterology risk stratification grid.6 Drug persistence of those on SC vedolizumab was compared with that of patients who remained on IV. Clinical data collected at baseline and at W12 included indication-specific disease activity scores (modified Harvey–Bradshaw Index [mHBI]15 or Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index [SCCAI]16), IBD-Control Patient Reported Outcomes Measures [PROMs],17 C-reactive protein [CRP], albumin, haemoglobin, platelet count, and FCP. A total of 7 patients had a clinically significant increase in FCP and therefore the FCP was repeated at approximately 24 weeks in these patients. Vedolizumab trough levels were measured at the baseline review in patients who had received at least three IV infusions previously and trough SC levels at W12, analysed at the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital using the Immundiagnostik IDKmonitor assay.

Safety data were collected at the W12 review and adverse drug reactions were reported via the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency [MHRA] Yellow Card Scheme. Patients who administered at least one dose of SC vedolizumab were included in the safety analysis. Patients were asked a series of questions regarding satisfaction with the process of transitioning to SC [Supplementary Figure 3, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online].

2.3. Statistical analysis

The mean change of disease activity according to the indication-specific activity score at W12 from baseline was calculated. Patients were classified as to whether they maintained baseline clinical status at W12. An increase in mHBI score of ≥3 [CD], SCCAI ≥2 [UC], and/or a decline in IBD-Control PROM score of ≥4 points, were classified as failure to maintain baseline clinical status. The proportion of patients maintaining baseline clinical status at W12 was reported with a 95% confidence interval [CI]. Severity of disease activity was divided into the following categories. For SCCAI: remission <3, mild 3–5, moderate 6–11 and severe ≥12; for mHBI: remission <5, mild 5–7, moderate 8–16, severe >16. For CRP and FCP: concentrations of <3 mg/L and <250 µg/g, respectively, were considered as acceptable. Combined remission was defined as remission on the indication-specific disease activity score combined with FCP <250 µg/g. Baseline and W12 IBD-Control PROMs were compared using a Wilcoxon signed rank test. Changes in levels of biochemical values between baseline and W12 were investigated using linear regression or the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Vedolizumab serum concentrations were compared using a paired Student’s t test, and the change in proportion of patients in combined remission according to vedolizumab concentration was analysed with the chi square test for trend. The log-rank test was used to assess persistence with the chosen route of administration. Risk factors for SARS-CoV-2, reasons for consenting or declining to transition to SC, patient experience, and adverse drug reactions were characterised with a descriptive analysis. The statistical analysis was performed with Stata [Release 16, StataCorp. LLC, TX, USA].

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

In all, 178 IBD patients treated with IV vedolizumab were offered the opportunity to transition from IV to SC, of whom 124 patients agreed to transition. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no clinically significant differences in demographics, baseline characteristics, or medication history among the patients who accepted or declined transition. All patients who switched to SC received a dose of 108 mg Q2W, and no patients underwent dose escalation during the follow-up period. The 106 patients of 124 had been on vedolizumab for more than 4 months [‘established transitioned’ cohort]. Of the 178 patients approached, 57 patients [32%] were reliant on others for transport to the infusion unit; 90 [51%] were employed; and 37 [21%] were retired. Patients reported that the median time taken to attend an infusion appointment [from leaving home to returning home] was 180 min (interquartile range [IQR]: 120–240 min). There was no correlation between the presence of risk factor[s] for a poor outcome from COVID-19 infection, time on vedolizumab, or previous experience of a self-administered SC medication, and the choice made by patients to transition to SC vedolizumab. The most common reasons given for patients accepting or declining the transition are shown in Table 2.

| . | All patients who transitioned to SC [n = 124] . | Established transitioned [n = 106] . | Patients who stayed on IV [n = 54] . | p-value [comparing transitioned and declined groups] . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New to vedolizumab [only received 2–3 IV doses] no. [%] | 17 [14%] | N/A | 8 [15%] | 0.50 |

| Age, median [range] years | 60 [19, 90] | 60 [20, 90] | 55 [21, 84] | 0.45 |

| Males, no. [%] | 57 [46%] | 48 [45%] | 23 [43%] | 0.68 |

| IBD diagnosis | ||||

| CD, no. [%] | 59 [48%] | 49 [46%] | 30 [56%] | 0.14 |

| UC, no. [%] | 57 [46%] | 50 [47%] | 24 [44%] | |

| IBDU, no. [%] | 8 [6%] | 7 [7%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Ethnicity, no. [%] | ||||

| White | 117 [94%] | 99 [93%] | 22 [41%] | 0.1 |

| Asian or Asian background | 2 [2%] | 2 [2%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Other | 1 [1%] | 1 [1%] | 2 [4%] | |

| Missing | 4 [3%] | 4 [4%] | 30 [56%] | |

| BMI, median [range] kg/m2 | 28 [16, 56] | 28 [16, 56] | 26 [18, 48] | 0.06 |

| Smoking status, no. [%] | ||||

| Non-smoker and never smoked | 50 [40%] | 41 [39%] | 9 [17%] | 0.45 |

| Previous smoker | 48 [39%] | 42 [40%] | 4 [7%] | |

| Current smoker | 15 [12%] | 12 [11%] | 1 [2%] | |

| Unknown | 6 [5%] | 6 [6%] | 31 [57%] | |

| Missing | 5 [4%] | 5 [5%] | 9 [17%] | |

| Age at onset [CD, no. [%] | ||||

| A1: ≤16 years | 7 [12%] | 5 [10%] | 1 [3%] | 0.8 |

| A2: 17–40 years | 22 [37%] | 20 [41%] | 6 [20%] | |

| A3: >40 years | 29 [49%] | 24 [49%] | 10 [33%] | |

| Missing | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | 13 [43%] | |

| Site of Crohn’s disease, no. [%] | ||||

| L1: Ileal | 17 [29%] | 14 [29%] | 3 [10%] | 0.61 |

| L2: Colonic | 18 [31%] | 16 [33%] | 7 [23%] | |

| L3: Ileocolonic | 23 [39%] | 19 [39%] | 7 [23%] | |

| L4: Upper gastrointestinal tract | 0 [0%] | 0 [0%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Missing | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | 13 [43%] | |

| Crohn’s disease behaviour, no. [%] | ||||

| B1: Non-stricturing/non-penetrating | 38 [64%] | 32 [65%] | 9 [30%] | 0.50 |

| B2: Stricturing | 16 [27%] | 13 [27%] | 6 [20%] | |

| B3: Penetrating | 3 [5%] | 3 [6%] | 2 [7%] | |

| Not applicable | 1 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Missing | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | 13 [43%] | |

| P: Perianal disease | 4 [7%] | 4 [8%] | 1 [3%] | 0.66 |

| Site of ulcerative colitis, no. [%] | ||||

| E1: Proctitis | 5 [9%] | 3 [6%] | 2 [8%] | 0.39 |

| E2: Left-sided | 25 [44%] | 22 [44%] | 13 [54%] | |

| E3: Extensive | 25 [44%] | 23 [46%] | 5 [21%] | |

| Not applicable | 1 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Missing | 1 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 4 [17%] | |

| Age at onset [UC], no. [%] | ||||

| <16 years | 1 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 1 [4%] | 0.45 |

| 16–40 years | 26 [40%] | 23 [40%] | 9 [38%] | |

| >40 years | 38 [58%] | 33 [58%] | 10 [42%] | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 4 [17%] | |

| Concomitant medications at baseline, no. [%] | ||||

| Thiopurine [azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine] | 5 [4%] | 4 [4%] | 2 [4%] | 1.00 |

| Methotrexate | 11 [9%] | 10 [9%] | 3 [6%] | 0.56 |

| Oral 5-ASA | 33 [27%] | 30 [28%] | 11 [20%] | 0.45 |

| Rectal 5-ASA | 2 [2%] | 1 [1%] | 5 [9%] | 0.03* |

| Oral steroid | 1 [1%] | 1 [1%] | 2 [4%] | 0.22 |

| Rectal steroid | 0 [0%] | 0 [0%] | 1 [2%] | 0.30 |

| Number of patients with at least one COVID-19 risk factor6 [%] | 78 [63%] | 60 [57%] | 27 [50%] | 0.14 |

| Median time [min] taken for patients to receive their IV infusion [leaving home to returning home] [range] | 180 [30, 360] | 173 [30, 300] | 150 [20, 360] | 0.12 |

| Mode of travel to infusion unit, no. [%] | ||||

| Drive/walk independently | 78 [63%] | 68 [64%] | 23 [43%] | 0.87 |

| Transported by family member | 32 [26%] | 26 [25%] | 12 [22%] | |

| Public transport | 9 [7%] | 9 [8%] | 3 [6%] | |

| Hospital transport | 1 [1%] | 0 [0%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Missing | 4 [3%] | 3 [3%] | 16 [30%] | |

| Median duration on vedolizumab, months [range] | 22 [1, 72] | 24 [5, 72] | 18 [1, 68] | 0.89 |

| Infusion frequency, no. [%] | ||||

| 4-weekly | 2 [2%] | 2 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 0.97 |

| 6-weekly | 28 [23%] | 28 [26%] | 11 [20%] | |

| 8-weekly | 92 [74%] | 74 [70%] | 42 [78%] | |

| Other [5- or 7-weekly] | 2 [2%] | 2 [2%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Previously self-injected subcutaneous medication, no. [%] | 64 [52%] | 54 [51%] | 29 [54%] | 0.87 |

| . | All patients who transitioned to SC [n = 124] . | Established transitioned [n = 106] . | Patients who stayed on IV [n = 54] . | p-value [comparing transitioned and declined groups] . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New to vedolizumab [only received 2–3 IV doses] no. [%] | 17 [14%] | N/A | 8 [15%] | 0.50 |

| Age, median [range] years | 60 [19, 90] | 60 [20, 90] | 55 [21, 84] | 0.45 |

| Males, no. [%] | 57 [46%] | 48 [45%] | 23 [43%] | 0.68 |

| IBD diagnosis | ||||

| CD, no. [%] | 59 [48%] | 49 [46%] | 30 [56%] | 0.14 |

| UC, no. [%] | 57 [46%] | 50 [47%] | 24 [44%] | |

| IBDU, no. [%] | 8 [6%] | 7 [7%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Ethnicity, no. [%] | ||||

| White | 117 [94%] | 99 [93%] | 22 [41%] | 0.1 |

| Asian or Asian background | 2 [2%] | 2 [2%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Other | 1 [1%] | 1 [1%] | 2 [4%] | |

| Missing | 4 [3%] | 4 [4%] | 30 [56%] | |

| BMI, median [range] kg/m2 | 28 [16, 56] | 28 [16, 56] | 26 [18, 48] | 0.06 |

| Smoking status, no. [%] | ||||

| Non-smoker and never smoked | 50 [40%] | 41 [39%] | 9 [17%] | 0.45 |

| Previous smoker | 48 [39%] | 42 [40%] | 4 [7%] | |

| Current smoker | 15 [12%] | 12 [11%] | 1 [2%] | |

| Unknown | 6 [5%] | 6 [6%] | 31 [57%] | |

| Missing | 5 [4%] | 5 [5%] | 9 [17%] | |

| Age at onset [CD, no. [%] | ||||

| A1: ≤16 years | 7 [12%] | 5 [10%] | 1 [3%] | 0.8 |

| A2: 17–40 years | 22 [37%] | 20 [41%] | 6 [20%] | |

| A3: >40 years | 29 [49%] | 24 [49%] | 10 [33%] | |

| Missing | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | 13 [43%] | |

| Site of Crohn’s disease, no. [%] | ||||

| L1: Ileal | 17 [29%] | 14 [29%] | 3 [10%] | 0.61 |

| L2: Colonic | 18 [31%] | 16 [33%] | 7 [23%] | |

| L3: Ileocolonic | 23 [39%] | 19 [39%] | 7 [23%] | |

| L4: Upper gastrointestinal tract | 0 [0%] | 0 [0%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Missing | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | 13 [43%] | |

| Crohn’s disease behaviour, no. [%] | ||||

| B1: Non-stricturing/non-penetrating | 38 [64%] | 32 [65%] | 9 [30%] | 0.50 |

| B2: Stricturing | 16 [27%] | 13 [27%] | 6 [20%] | |

| B3: Penetrating | 3 [5%] | 3 [6%] | 2 [7%] | |

| Not applicable | 1 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Missing | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | 13 [43%] | |

| P: Perianal disease | 4 [7%] | 4 [8%] | 1 [3%] | 0.66 |

| Site of ulcerative colitis, no. [%] | ||||

| E1: Proctitis | 5 [9%] | 3 [6%] | 2 [8%] | 0.39 |

| E2: Left-sided | 25 [44%] | 22 [44%] | 13 [54%] | |

| E3: Extensive | 25 [44%] | 23 [46%] | 5 [21%] | |

| Not applicable | 1 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Missing | 1 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 4 [17%] | |

| Age at onset [UC], no. [%] | ||||

| <16 years | 1 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 1 [4%] | 0.45 |

| 16–40 years | 26 [40%] | 23 [40%] | 9 [38%] | |

| >40 years | 38 [58%] | 33 [58%] | 10 [42%] | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 4 [17%] | |

| Concomitant medications at baseline, no. [%] | ||||

| Thiopurine [azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine] | 5 [4%] | 4 [4%] | 2 [4%] | 1.00 |

| Methotrexate | 11 [9%] | 10 [9%] | 3 [6%] | 0.56 |

| Oral 5-ASA | 33 [27%] | 30 [28%] | 11 [20%] | 0.45 |

| Rectal 5-ASA | 2 [2%] | 1 [1%] | 5 [9%] | 0.03* |

| Oral steroid | 1 [1%] | 1 [1%] | 2 [4%] | 0.22 |

| Rectal steroid | 0 [0%] | 0 [0%] | 1 [2%] | 0.30 |

| Number of patients with at least one COVID-19 risk factor6 [%] | 78 [63%] | 60 [57%] | 27 [50%] | 0.14 |

| Median time [min] taken for patients to receive their IV infusion [leaving home to returning home] [range] | 180 [30, 360] | 173 [30, 300] | 150 [20, 360] | 0.12 |

| Mode of travel to infusion unit, no. [%] | ||||

| Drive/walk independently | 78 [63%] | 68 [64%] | 23 [43%] | 0.87 |

| Transported by family member | 32 [26%] | 26 [25%] | 12 [22%] | |

| Public transport | 9 [7%] | 9 [8%] | 3 [6%] | |

| Hospital transport | 1 [1%] | 0 [0%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Missing | 4 [3%] | 3 [3%] | 16 [30%] | |

| Median duration on vedolizumab, months [range] | 22 [1, 72] | 24 [5, 72] | 18 [1, 68] | 0.89 |

| Infusion frequency, no. [%] | ||||

| 4-weekly | 2 [2%] | 2 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 0.97 |

| 6-weekly | 28 [23%] | 28 [26%] | 11 [20%] | |

| 8-weekly | 92 [74%] | 74 [70%] | 42 [78%] | |

| Other [5- or 7-weekly] | 2 [2%] | 2 [2%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Previously self-injected subcutaneous medication, no. [%] | 64 [52%] | 54 [51%] | 29 [54%] | 0.87 |

No., number; BMI, body mass index; 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous; IBDU, inflammatory bowel disease unclassified; UC, ulcerative colitis; CD, Crohn’s disease; N/A, not available.

* indicates a statistically significant difference.

| . | All patients who transitioned to SC [n = 124] . | Established transitioned [n = 106] . | Patients who stayed on IV [n = 54] . | p-value [comparing transitioned and declined groups] . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New to vedolizumab [only received 2–3 IV doses] no. [%] | 17 [14%] | N/A | 8 [15%] | 0.50 |

| Age, median [range] years | 60 [19, 90] | 60 [20, 90] | 55 [21, 84] | 0.45 |

| Males, no. [%] | 57 [46%] | 48 [45%] | 23 [43%] | 0.68 |

| IBD diagnosis | ||||

| CD, no. [%] | 59 [48%] | 49 [46%] | 30 [56%] | 0.14 |

| UC, no. [%] | 57 [46%] | 50 [47%] | 24 [44%] | |

| IBDU, no. [%] | 8 [6%] | 7 [7%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Ethnicity, no. [%] | ||||

| White | 117 [94%] | 99 [93%] | 22 [41%] | 0.1 |

| Asian or Asian background | 2 [2%] | 2 [2%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Other | 1 [1%] | 1 [1%] | 2 [4%] | |

| Missing | 4 [3%] | 4 [4%] | 30 [56%] | |

| BMI, median [range] kg/m2 | 28 [16, 56] | 28 [16, 56] | 26 [18, 48] | 0.06 |

| Smoking status, no. [%] | ||||

| Non-smoker and never smoked | 50 [40%] | 41 [39%] | 9 [17%] | 0.45 |

| Previous smoker | 48 [39%] | 42 [40%] | 4 [7%] | |

| Current smoker | 15 [12%] | 12 [11%] | 1 [2%] | |

| Unknown | 6 [5%] | 6 [6%] | 31 [57%] | |

| Missing | 5 [4%] | 5 [5%] | 9 [17%] | |

| Age at onset [CD, no. [%] | ||||

| A1: ≤16 years | 7 [12%] | 5 [10%] | 1 [3%] | 0.8 |

| A2: 17–40 years | 22 [37%] | 20 [41%] | 6 [20%] | |

| A3: >40 years | 29 [49%] | 24 [49%] | 10 [33%] | |

| Missing | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | 13 [43%] | |

| Site of Crohn’s disease, no. [%] | ||||

| L1: Ileal | 17 [29%] | 14 [29%] | 3 [10%] | 0.61 |

| L2: Colonic | 18 [31%] | 16 [33%] | 7 [23%] | |

| L3: Ileocolonic | 23 [39%] | 19 [39%] | 7 [23%] | |

| L4: Upper gastrointestinal tract | 0 [0%] | 0 [0%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Missing | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | 13 [43%] | |

| Crohn’s disease behaviour, no. [%] | ||||

| B1: Non-stricturing/non-penetrating | 38 [64%] | 32 [65%] | 9 [30%] | 0.50 |

| B2: Stricturing | 16 [27%] | 13 [27%] | 6 [20%] | |

| B3: Penetrating | 3 [5%] | 3 [6%] | 2 [7%] | |

| Not applicable | 1 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Missing | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | 13 [43%] | |

| P: Perianal disease | 4 [7%] | 4 [8%] | 1 [3%] | 0.66 |

| Site of ulcerative colitis, no. [%] | ||||

| E1: Proctitis | 5 [9%] | 3 [6%] | 2 [8%] | 0.39 |

| E2: Left-sided | 25 [44%] | 22 [44%] | 13 [54%] | |

| E3: Extensive | 25 [44%] | 23 [46%] | 5 [21%] | |

| Not applicable | 1 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Missing | 1 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 4 [17%] | |

| Age at onset [UC], no. [%] | ||||

| <16 years | 1 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 1 [4%] | 0.45 |

| 16–40 years | 26 [40%] | 23 [40%] | 9 [38%] | |

| >40 years | 38 [58%] | 33 [58%] | 10 [42%] | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 4 [17%] | |

| Concomitant medications at baseline, no. [%] | ||||

| Thiopurine [azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine] | 5 [4%] | 4 [4%] | 2 [4%] | 1.00 |

| Methotrexate | 11 [9%] | 10 [9%] | 3 [6%] | 0.56 |

| Oral 5-ASA | 33 [27%] | 30 [28%] | 11 [20%] | 0.45 |

| Rectal 5-ASA | 2 [2%] | 1 [1%] | 5 [9%] | 0.03* |

| Oral steroid | 1 [1%] | 1 [1%] | 2 [4%] | 0.22 |

| Rectal steroid | 0 [0%] | 0 [0%] | 1 [2%] | 0.30 |

| Number of patients with at least one COVID-19 risk factor6 [%] | 78 [63%] | 60 [57%] | 27 [50%] | 0.14 |

| Median time [min] taken for patients to receive their IV infusion [leaving home to returning home] [range] | 180 [30, 360] | 173 [30, 300] | 150 [20, 360] | 0.12 |

| Mode of travel to infusion unit, no. [%] | ||||

| Drive/walk independently | 78 [63%] | 68 [64%] | 23 [43%] | 0.87 |

| Transported by family member | 32 [26%] | 26 [25%] | 12 [22%] | |

| Public transport | 9 [7%] | 9 [8%] | 3 [6%] | |

| Hospital transport | 1 [1%] | 0 [0%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Missing | 4 [3%] | 3 [3%] | 16 [30%] | |

| Median duration on vedolizumab, months [range] | 22 [1, 72] | 24 [5, 72] | 18 [1, 68] | 0.89 |

| Infusion frequency, no. [%] | ||||

| 4-weekly | 2 [2%] | 2 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 0.97 |

| 6-weekly | 28 [23%] | 28 [26%] | 11 [20%] | |

| 8-weekly | 92 [74%] | 74 [70%] | 42 [78%] | |

| Other [5- or 7-weekly] | 2 [2%] | 2 [2%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Previously self-injected subcutaneous medication, no. [%] | 64 [52%] | 54 [51%] | 29 [54%] | 0.87 |

| . | All patients who transitioned to SC [n = 124] . | Established transitioned [n = 106] . | Patients who stayed on IV [n = 54] . | p-value [comparing transitioned and declined groups] . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New to vedolizumab [only received 2–3 IV doses] no. [%] | 17 [14%] | N/A | 8 [15%] | 0.50 |

| Age, median [range] years | 60 [19, 90] | 60 [20, 90] | 55 [21, 84] | 0.45 |

| Males, no. [%] | 57 [46%] | 48 [45%] | 23 [43%] | 0.68 |

| IBD diagnosis | ||||

| CD, no. [%] | 59 [48%] | 49 [46%] | 30 [56%] | 0.14 |

| UC, no. [%] | 57 [46%] | 50 [47%] | 24 [44%] | |

| IBDU, no. [%] | 8 [6%] | 7 [7%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Ethnicity, no. [%] | ||||

| White | 117 [94%] | 99 [93%] | 22 [41%] | 0.1 |

| Asian or Asian background | 2 [2%] | 2 [2%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Other | 1 [1%] | 1 [1%] | 2 [4%] | |

| Missing | 4 [3%] | 4 [4%] | 30 [56%] | |

| BMI, median [range] kg/m2 | 28 [16, 56] | 28 [16, 56] | 26 [18, 48] | 0.06 |

| Smoking status, no. [%] | ||||

| Non-smoker and never smoked | 50 [40%] | 41 [39%] | 9 [17%] | 0.45 |

| Previous smoker | 48 [39%] | 42 [40%] | 4 [7%] | |

| Current smoker | 15 [12%] | 12 [11%] | 1 [2%] | |

| Unknown | 6 [5%] | 6 [6%] | 31 [57%] | |

| Missing | 5 [4%] | 5 [5%] | 9 [17%] | |

| Age at onset [CD, no. [%] | ||||

| A1: ≤16 years | 7 [12%] | 5 [10%] | 1 [3%] | 0.8 |

| A2: 17–40 years | 22 [37%] | 20 [41%] | 6 [20%] | |

| A3: >40 years | 29 [49%] | 24 [49%] | 10 [33%] | |

| Missing | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | 13 [43%] | |

| Site of Crohn’s disease, no. [%] | ||||

| L1: Ileal | 17 [29%] | 14 [29%] | 3 [10%] | 0.61 |

| L2: Colonic | 18 [31%] | 16 [33%] | 7 [23%] | |

| L3: Ileocolonic | 23 [39%] | 19 [39%] | 7 [23%] | |

| L4: Upper gastrointestinal tract | 0 [0%] | 0 [0%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Missing | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | 13 [43%] | |

| Crohn’s disease behaviour, no. [%] | ||||

| B1: Non-stricturing/non-penetrating | 38 [64%] | 32 [65%] | 9 [30%] | 0.50 |

| B2: Stricturing | 16 [27%] | 13 [27%] | 6 [20%] | |

| B3: Penetrating | 3 [5%] | 3 [6%] | 2 [7%] | |

| Not applicable | 1 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Missing | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | 13 [43%] | |

| P: Perianal disease | 4 [7%] | 4 [8%] | 1 [3%] | 0.66 |

| Site of ulcerative colitis, no. [%] | ||||

| E1: Proctitis | 5 [9%] | 3 [6%] | 2 [8%] | 0.39 |

| E2: Left-sided | 25 [44%] | 22 [44%] | 13 [54%] | |

| E3: Extensive | 25 [44%] | 23 [46%] | 5 [21%] | |

| Not applicable | 1 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Missing | 1 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 4 [17%] | |

| Age at onset [UC], no. [%] | ||||

| <16 years | 1 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 1 [4%] | 0.45 |

| 16–40 years | 26 [40%] | 23 [40%] | 9 [38%] | |

| >40 years | 38 [58%] | 33 [58%] | 10 [42%] | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 4 [17%] | |

| Concomitant medications at baseline, no. [%] | ||||

| Thiopurine [azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine] | 5 [4%] | 4 [4%] | 2 [4%] | 1.00 |

| Methotrexate | 11 [9%] | 10 [9%] | 3 [6%] | 0.56 |

| Oral 5-ASA | 33 [27%] | 30 [28%] | 11 [20%] | 0.45 |

| Rectal 5-ASA | 2 [2%] | 1 [1%] | 5 [9%] | 0.03* |

| Oral steroid | 1 [1%] | 1 [1%] | 2 [4%] | 0.22 |

| Rectal steroid | 0 [0%] | 0 [0%] | 1 [2%] | 0.30 |

| Number of patients with at least one COVID-19 risk factor6 [%] | 78 [63%] | 60 [57%] | 27 [50%] | 0.14 |

| Median time [min] taken for patients to receive their IV infusion [leaving home to returning home] [range] | 180 [30, 360] | 173 [30, 300] | 150 [20, 360] | 0.12 |

| Mode of travel to infusion unit, no. [%] | ||||

| Drive/walk independently | 78 [63%] | 68 [64%] | 23 [43%] | 0.87 |

| Transported by family member | 32 [26%] | 26 [25%] | 12 [22%] | |

| Public transport | 9 [7%] | 9 [8%] | 3 [6%] | |

| Hospital transport | 1 [1%] | 0 [0%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Missing | 4 [3%] | 3 [3%] | 16 [30%] | |

| Median duration on vedolizumab, months [range] | 22 [1, 72] | 24 [5, 72] | 18 [1, 68] | 0.89 |

| Infusion frequency, no. [%] | ||||

| 4-weekly | 2 [2%] | 2 [2%] | 1 [2%] | 0.97 |

| 6-weekly | 28 [23%] | 28 [26%] | 11 [20%] | |

| 8-weekly | 92 [74%] | 74 [70%] | 42 [78%] | |

| Other [5- or 7-weekly] | 2 [2%] | 2 [2%] | 0 [0%] | |

| Previously self-injected subcutaneous medication, no. [%] | 64 [52%] | 54 [51%] | 29 [54%] | 0.87 |

No., number; BMI, body mass index; 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous; IBDU, inflammatory bowel disease unclassified; UC, ulcerative colitis; CD, Crohn’s disease; N/A, not available.

* indicates a statistically significant difference.

| Reason for transitioning [n = 124] . | No. [%] . | Reason for not transitioning [n = 54] . | No. [%] . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preference to self-manage treatment at home | 93 [75%] | Preference to not self-inject | 20 [37%] |

| Poor access to infusion unit | 26 [21%] | Concern about the needle | 13 [24.1%] |

| Prevent exposure to hospital/nosocomial infection | 19 [15.3%] | Feels safer attending infusion unit/concerns about lack of nursing contact | 10 [18.5%] |

| Recurrence of symptoms before next dose due | 16 [12.9%] | Current poorly controlled disease | 6 [11.1%] |

| Poor venous access | 11 [8.9%] | Requires premedication due to previous allergy | 5 [9.3%] |

| Reason for transitioning [n = 124] . | No. [%] . | Reason for not transitioning [n = 54] . | No. [%] . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preference to self-manage treatment at home | 93 [75%] | Preference to not self-inject | 20 [37%] |

| Poor access to infusion unit | 26 [21%] | Concern about the needle | 13 [24.1%] |

| Prevent exposure to hospital/nosocomial infection | 19 [15.3%] | Feels safer attending infusion unit/concerns about lack of nursing contact | 10 [18.5%] |

| Recurrence of symptoms before next dose due | 16 [12.9%] | Current poorly controlled disease | 6 [11.1%] |

| Poor venous access | 11 [8.9%] | Requires premedication due to previous allergy | 5 [9.3%] |

| Reason for transitioning [n = 124] . | No. [%] . | Reason for not transitioning [n = 54] . | No. [%] . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preference to self-manage treatment at home | 93 [75%] | Preference to not self-inject | 20 [37%] |

| Poor access to infusion unit | 26 [21%] | Concern about the needle | 13 [24.1%] |

| Prevent exposure to hospital/nosocomial infection | 19 [15.3%] | Feels safer attending infusion unit/concerns about lack of nursing contact | 10 [18.5%] |

| Recurrence of symptoms before next dose due | 16 [12.9%] | Current poorly controlled disease | 6 [11.1%] |

| Poor venous access | 11 [8.9%] | Requires premedication due to previous allergy | 5 [9.3%] |

| Reason for transitioning [n = 124] . | No. [%] . | Reason for not transitioning [n = 54] . | No. [%] . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preference to self-manage treatment at home | 93 [75%] | Preference to not self-inject | 20 [37%] |

| Poor access to infusion unit | 26 [21%] | Concern about the needle | 13 [24.1%] |

| Prevent exposure to hospital/nosocomial infection | 19 [15.3%] | Feels safer attending infusion unit/concerns about lack of nursing contact | 10 [18.5%] |

| Recurrence of symptoms before next dose due | 16 [12.9%] | Current poorly controlled disease | 6 [11.1%] |

| Poor venous access | 11 [8.9%] | Requires premedication due to previous allergy | 5 [9.3%] |

3.2. Clinical and biochemical effectiveness

There were no significant differences in disease activity scores or IBD-Control PROMs between the population of patients who transitioned to SC and those who stayed on IV [Table 3]; 84% [104/124] [95% CI: 77%–90%] maintained their baseline clinical status following transition to SC. There were no statistically significant differences in disease activity scores or IBD-Control PROMs between baseline and W12. The distribution of the disease activity of patients established on vedolizumab [n = 106] who transitioned was similar at baseline and at W12 [p = 0.13] [Figure 2].

Comparison of disease activity scores in patients established on vedolizumab infusions.

| Variable . | Cohort . | Baseline . | W12 . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mHBI [CD], median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 21] | 3.5 [1, 6] | - | - |

| Transitioned [n = 45] | 3 [1, 6] | 2 [1, 5] | 0.13 | |

| SCCAI [UC], median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 19] | 2.5 [1, 4] | - | - |

| Transitioned [n = 55] | 2 [1, 4] | 1.5 [0, 3] | 0.05 | |

| IBD-Control-8, median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 40] | 13 [9.5, 14.5] | - | - |

| Transitioned [n = 104] | 14 [10, 16] | 14 [12, 16] | 0.09 | |

| IBD-Control Visual Analogue Scale [VAS], median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 38] | 87.5 [70, 95] | - | - |

| Transitioned [n = 102] | 85 [75, 95] | 85 [75, 95] | 0.58 |

| Variable . | Cohort . | Baseline . | W12 . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mHBI [CD], median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 21] | 3.5 [1, 6] | - | - |

| Transitioned [n = 45] | 3 [1, 6] | 2 [1, 5] | 0.13 | |

| SCCAI [UC], median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 19] | 2.5 [1, 4] | - | - |

| Transitioned [n = 55] | 2 [1, 4] | 1.5 [0, 3] | 0.05 | |

| IBD-Control-8, median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 40] | 13 [9.5, 14.5] | - | - |

| Transitioned [n = 104] | 14 [10, 16] | 14 [12, 16] | 0.09 | |

| IBD-Control Visual Analogue Scale [VAS], median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 38] | 87.5 [70, 95] | - | - |

| Transitioned [n = 102] | 85 [75, 95] | 85 [75, 95] | 0.58 |

CD, Crohn’s disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; mHBI, modified Harvey–Bradshaw Index; IQR, interquartile range; SCCAI, Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index.

Comparison of disease activity scores in patients established on vedolizumab infusions.

| Variable . | Cohort . | Baseline . | W12 . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mHBI [CD], median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 21] | 3.5 [1, 6] | - | - |

| Transitioned [n = 45] | 3 [1, 6] | 2 [1, 5] | 0.13 | |

| SCCAI [UC], median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 19] | 2.5 [1, 4] | - | - |

| Transitioned [n = 55] | 2 [1, 4] | 1.5 [0, 3] | 0.05 | |

| IBD-Control-8, median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 40] | 13 [9.5, 14.5] | - | - |

| Transitioned [n = 104] | 14 [10, 16] | 14 [12, 16] | 0.09 | |

| IBD-Control Visual Analogue Scale [VAS], median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 38] | 87.5 [70, 95] | - | - |

| Transitioned [n = 102] | 85 [75, 95] | 85 [75, 95] | 0.58 |

| Variable . | Cohort . | Baseline . | W12 . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mHBI [CD], median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 21] | 3.5 [1, 6] | - | - |

| Transitioned [n = 45] | 3 [1, 6] | 2 [1, 5] | 0.13 | |

| SCCAI [UC], median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 19] | 2.5 [1, 4] | - | - |

| Transitioned [n = 55] | 2 [1, 4] | 1.5 [0, 3] | 0.05 | |

| IBD-Control-8, median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 40] | 13 [9.5, 14.5] | - | - |

| Transitioned [n = 104] | 14 [10, 16] | 14 [12, 16] | 0.09 | |

| IBD-Control Visual Analogue Scale [VAS], median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 38] | 87.5 [70, 95] | - | - |

| Transitioned [n = 102] | 85 [75, 95] | 85 [75, 95] | 0.58 |

CD, Crohn’s disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; mHBI, modified Harvey–Bradshaw Index; IQR, interquartile range; SCCAI, Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index.

![Disease activity in established patients at baseline and W12 [n = 106; p = 0.13].](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ecco-jcc/16/6/10.1093_ecco-jcc_jjab224/1/m_jjab224f0002.jpeg?Expires=1750191103&Signature=iucK47rJ2XKQEBxYTkZbkkeBG5foFbx~HZ5FyF5uxoOtCNYYkaxhwAApJqsMO-hRvJp3Ub4MHd5bX~Kl32oNrIhRd4wYHLvNHYqztDEirujUSLGlZzVoFeKhNkR080ssrr14s~TgFxmd4h9HpWIFgRAtMTPmYtWw7NxTso6WM044ocT3QdwCO5Xv5surjmt1XK1majzsOU8GN~aekqxS4lanA22WBHsPJX6BaJ4lQxNmdTPbqaTKU7A-0nwnbN4RehZgGHa8z-Te7LtloQvYDX75A3t6Dd-67xZkk07MVcCtuIcR7~~YhgxEVclpNRZak1Vs04IknBoGyD4qWIZJjQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Disease activity in established patients at baseline and W12 [n = 106; p = 0.13].

There were no clinically significant differences in CRP, albumin, haemoglobin, or platelet count between patients who transitioned or declined to transition, or between patients who transitioned at baseline and W12. However, a statistically significant increase in FCP was observed in patients who switched at W12 compared with baseline, although the change of median FCP from 31 µg/g to 47 µg/g was unlikely to be clinically relevant [Table 4]. A FCP of below 250 µg/g is considered an optimal target for achieving disease remission in IBD patients.18 A total of seven patients in the established cohort had a potentially clinically significant increase in their FCP at W12, without a worsening in disease activity scores. These had normalised at approximately Week 24 in all but one case who was asymptomatic and is undergoing further assessment [Supplementary Figure 4, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online].

Comparison of biochemical markers in patients established on vedolizumab infusions.

| Variable . | Cohort . | Baseline . | W12 . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-reactive protein mg/L, median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 44] | 2 [1, 5.5] | - | - |

| Transitioned[n = 98] | 3 [1, 7] | 3 [1, 7] | 0.45 | |

| Faecal calprotectin µg/g, median[IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 35] | 17 [7.9, 136] | - | - |

| Transitioned[n = 80] | 31 [12, 153.5] | 47 [13, 257] | 0.008 |

| Variable . | Cohort . | Baseline . | W12 . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-reactive protein mg/L, median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 44] | 2 [1, 5.5] | - | - |

| Transitioned[n = 98] | 3 [1, 7] | 3 [1, 7] | 0.45 | |

| Faecal calprotectin µg/g, median[IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 35] | 17 [7.9, 136] | - | - |

| Transitioned[n = 80] | 31 [12, 153.5] | 47 [13, 257] | 0.008 |

IQR, interquartile range.

Comparison of biochemical markers in patients established on vedolizumab infusions.

| Variable . | Cohort . | Baseline . | W12 . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-reactive protein mg/L, median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 44] | 2 [1, 5.5] | - | - |

| Transitioned[n = 98] | 3 [1, 7] | 3 [1, 7] | 0.45 | |

| Faecal calprotectin µg/g, median[IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 35] | 17 [7.9, 136] | - | - |

| Transitioned[n = 80] | 31 [12, 153.5] | 47 [13, 257] | 0.008 |

| Variable . | Cohort . | Baseline . | W12 . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-reactive protein mg/L, median [IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 44] | 2 [1, 5.5] | - | - |

| Transitioned[n = 98] | 3 [1, 7] | 3 [1, 7] | 0.45 | |

| Faecal calprotectin µg/g, median[IQR] | Declined to transition [n = 35] | 17 [7.9, 136] | - | - |

| Transitioned[n = 80] | 31 [12, 153.5] | 47 [13, 257] | 0.008 |

IQR, interquartile range.

3.3. Drug persistence

Persistence on vedolizumab continued to be assessed beyond the 12 weeks of the service evaluation and was compared for those patients accepting and declining the transition, with no significant difference between the two groups [p = 0.5; Figure 3]. Failure for the SC cohort was defined as reverse transition to IV or discontinuation of vedolizumab. The persistence rate at W12 was high [92%]. The reasons for failure on SC at W12 were adverse events related to injecting [n = 5], other adverse events [n = 3], and secondary loss of response [n = 2].

![Kaplan–Meier drug persistence curve for patients who transitioned [blue solid line] vs. those who stayed on intravenous [IV] vedolizumab [red dashed line] [p = 0.5].](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ecco-jcc/16/6/10.1093_ecco-jcc_jjab224/1/m_jjab224f0003.jpeg?Expires=1750191103&Signature=ZW99uaylQTOgA0aaaVDlZ6w5fWTjMTUnD3mGzp3F75h-jwGznZ7oWpSrklVlb5Op4bftPeaK-zpzZFTTSptmza6v2KUDdW17F764Xj5EJFzO1lKl9AGDwzgRRu6M2bmYyYWCunqO49IRB8cK8dg4klt0T54v3NXB3cLEBDGX~niXJPqhZcFTVOMPomAnK4D~8GvTT0jL~3ub7qwNnaapZXBrZtk975muNkvDgWmt7H1RcDnvxdoryrQtBpp-rFqFY89wnwBN7fpIcHfJI6x7RBJY6lOyVFWK6oNxjp-uiYLG3Ge-qiV-mnIxe03Nrhn-HZORCjhP1PrBoIFz3Qe93g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Kaplan–Meier drug persistence curve for patients who transitioned [blue solid line] vs. those who stayed on intravenous [IV] vedolizumab [red dashed line] [p = 0.5].

In post hoc analyses, there were no differences in proportion of patients achieving combined remission or persistence on SC between those who previously received IV infusions more often than 8-weekly versus those on 8-weekly infusions [Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online]. There was no difference in persistence on SC at W12, or in maintaining baseline clinical status, in patients who were in remission at baseline versus those who had active disease [Supplementary Table 3, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online].

3.4. Adverse drug reactions

The most common adverse drug reactions reported were injection site reactions, joint pain, rashes, and headaches [Table 5]. Other adverse events reported were thought to be unrelated to the transitioning process [Supplementary Table 4, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online]. Pain experienced on injection was assessed using a validated visual analogue scale [VAS].19 On a scale of 0 to 100, median pain score reported was 10 [IQR: 0–30] and seven patients reported severe pain [VAS score ≥70].

Adverse drug reactions reported by patients at W12 after transitioning to SC vedolizumab.

| Adverse drug reaction . | Number of patients, 12 weeks post transitioning to SC [%] [n = 124] . |

|---|---|

| Injection site reaction | 18 [14.5%] |

| Joint pain | 10 [8.1%] |

| Muscle spasm | 4 [3.2%] |

| Blurred vision | 5 [4.0%] |

| Rashes | 10 [8.1%] |

| Headaches | 7 [5.6%] |

| Infections requiring antibiotics | 5 [4.0%] |

| Infections requiring no antibiotics | 3 [2.4%] |

| Pins and needles/tingling | 5 [4.0%] |

| Other | 3 [2.4%] |

| Adverse drug reaction . | Number of patients, 12 weeks post transitioning to SC [%] [n = 124] . |

|---|---|

| Injection site reaction | 18 [14.5%] |

| Joint pain | 10 [8.1%] |

| Muscle spasm | 4 [3.2%] |

| Blurred vision | 5 [4.0%] |

| Rashes | 10 [8.1%] |

| Headaches | 7 [5.6%] |

| Infections requiring antibiotics | 5 [4.0%] |

| Infections requiring no antibiotics | 3 [2.4%] |

| Pins and needles/tingling | 5 [4.0%] |

| Other | 3 [2.4%] |

Other: hair loss, fatigue, ‘spaced out’.

SC, subcutaneous.

Adverse drug reactions reported by patients at W12 after transitioning to SC vedolizumab.

| Adverse drug reaction . | Number of patients, 12 weeks post transitioning to SC [%] [n = 124] . |

|---|---|

| Injection site reaction | 18 [14.5%] |

| Joint pain | 10 [8.1%] |

| Muscle spasm | 4 [3.2%] |

| Blurred vision | 5 [4.0%] |

| Rashes | 10 [8.1%] |

| Headaches | 7 [5.6%] |

| Infections requiring antibiotics | 5 [4.0%] |

| Infections requiring no antibiotics | 3 [2.4%] |

| Pins and needles/tingling | 5 [4.0%] |

| Other | 3 [2.4%] |

| Adverse drug reaction . | Number of patients, 12 weeks post transitioning to SC [%] [n = 124] . |

|---|---|

| Injection site reaction | 18 [14.5%] |

| Joint pain | 10 [8.1%] |

| Muscle spasm | 4 [3.2%] |

| Blurred vision | 5 [4.0%] |

| Rashes | 10 [8.1%] |

| Headaches | 7 [5.6%] |

| Infections requiring antibiotics | 5 [4.0%] |

| Infections requiring no antibiotics | 3 [2.4%] |

| Pins and needles/tingling | 5 [4.0%] |

| Other | 3 [2.4%] |

Other: hair loss, fatigue, ‘spaced out’.

SC, subcutaneous.

3.5. Pharmacokinetics

In patients established on vedolizumab with paired results, the mean trough serum vedolizumab concentration at steady state at baseline and then at W12 [Ctrough,ss] increased from 10 to 22.7 mg/L. The proportion of patients in remission at W12 was higher with increasing vedolizumab concentration [p = 0.03; Figure 4] from 40% [quartile 1] to 68% [quartile 4]. No patients with anti-vedolizumab antibodies were identified, although it is acknowledged that a drug-sensitive assay was used. Immunogenicity with vedolizumab is thought to be low.20

![Combined remission [disease activity score indicating remission and FCP ≤250 µg/g] at W12 by trough concentration quartile in patients transitioning to SC [p = 0.03].FCP, faecal calprotectin; SC, subcutaneous.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ecco-jcc/16/6/10.1093_ecco-jcc_jjab224/1/m_jjab224f0004.jpeg?Expires=1750191103&Signature=BmQFQMmMr7hA42YtizP1ywZIR5Xmu~qy656yCOAIx1tdoPQ7UYi933c6xPTA3WuYqkYwOKRwlDWAtfMh1fGI00MNWsL~kEO94BHJmFeB71X5VAAKEoT~SrcER--yqQvWsOAgUng~g8bgX8QXLlFPealv3on51x0RZ32yb2TE-KJKfrCxJRReJV8PxMH7vA0wf5OC~04Bww-ZUOPyKPWMgV27gE4PghAQbMenJS34PLzdlr06bWXxcd2nhMx6GsKyDsrL4Qgm1Y1vu5M~FTJ9zMj654r2GGApEd9R5DYGCOV7NPlBYm7LNZMIGO6nEmG9Rn~D9gUPZxnDgHw5N6LdSw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Combined remission [disease activity score indicating remission and FCP ≤250 µg/g] at W12 by trough concentration quartile in patients transitioning to SC [p = 0.03].FCP, faecal calprotectin; SC, subcutaneous.

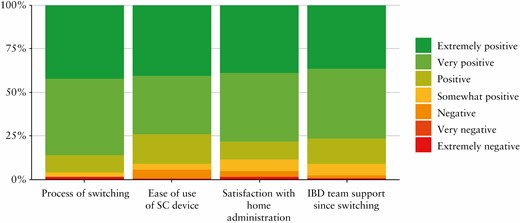

3.6. Patient satisfaction and impact on the health service

The majority of patients had a positive experience during the process of transitioning and reported feeling supported throughout the process. There was a high degree of satisfaction with being able to administer vedolizumab at home, and most patients reported that the SC devices were easy to use [Figure 5]. When patients were asked to summarise their experience of transitioning to SC administration, the most commonly occurring words were ‘easy’ and ‘convenient’ [Supplementary Figure 5, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online].

The net drug acquisition cost of SC vedolizumab [dosed at 108 mg Q2W] is equivalent to IV administered at standard dosing [300 mg Q8W]. Modelling the annual drug acquisition costs using data from our cohort of patients [accounting for prior infusion frequency and patients reverting to IV], an expected reduction in annual drug acquisition costs of £357,000 per 100 patients transitioned is likely to be achieved, split between VAT savings associated with homecare drug supply and additional costs of IV administered more frequently than Q8W [Figure 6]. Additional savings associated with reduction in administration of IV infusions [such as staffing, estate, and ancillary costs], using a conservative estimate based on the NICE costing for the administration of an infusion,21 are estimated to be in the region of £104,000 per annum per 100 patients transitioned.

![Impact of subcutaneous [SC] vedolizumab implementation on local drug acquisition costs.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ecco-jcc/16/6/10.1093_ecco-jcc_jjab224/1/m_jjab224f0006.jpeg?Expires=1750191103&Signature=BDdakA1Miyq-GVSK4Yhdp9D8kmMADWMzm-es31rzreD9z1K52H7KckK281Wg4UCjygIz~JOKwJCkw9g1ItnpJXF2Me6YHxGQpx94bY2Qaig2MnW9-kgMcPFaetYIgH~lRXlbSyjvPj8RSDJMNIJnvHQCHMjsMgm8AI1jfrdjxj5M9noRyv6K0cex8WHFRLn-k7ix1jL5p-bH5eBs9PZ8a7jYGGxCTMt6dudymeZKt9Ta290~KRo12PuJhEUbsrlgx~1nPT6ljInYK6xNacDe-Ie6GtDSyDDxTyHLBPThoCxzKGKxVgmVlBTvNZK62Z3gaUtdJjqG9O9gtUQEW9AYbQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Impact of subcutaneous [SC] vedolizumab implementation on local drug acquisition costs.

The local infusion service, in common with many infusion units across the UK, has a lack of capacity resulting in long waits for patients initiating new treatments. This delay reduced from an average of 30 days to 21 in the months following the transition to SC vedolizumab, despite an increase in average monthly referrals to the service [from 83 to 111] [Supplementary Figure 6, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online], and allowed for the introduction of new therapies to the unit such as targeted therapies for the treatment of asthma. There were no other interventions at the infusion unit which were likely to have affected this waiting time during this period.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first description of the transition of a real-world cohort of patients with IBD established on IV vedolizumab to SC. At the time of starting the transitioning programme, reducing hospital visits was a key part of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the absence of data around outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with IBD.6,22 This service evaluation was designed to evaluate the clinical effectiveness, safety, and patient satisfaction outcomes associated with the transition.

Understanding patients’ reasons for preference of a certain route of administration allows shared decision making.23,24 There were no factors identified in this programme, for example previous experience self-injecting or age, which correlated with patients choosing to switch to the SC route. Approximately 30% of patients declined to transition to SC, and it is important to recognise that there is a group of patients not suitable for self-administration for practical reasons or previous non-compliance.

There were no clinically significant differences in any clinical or laboratory measures 12 weeks after transition to SC in patients who were established on vedolizumab. Although there was a statistically significant increase in FCP at W12, this did not translate into a worsening of disease activity scores, patient-reported outcomes, or change in therapy. Careful consideration is required if there is objective evidence of active disease, but this should not preclude offering SC.

Tolerability was high, with injection site reactions being the most commonly reported adverse drug reaction related to the transition. In the majority of cases, the pain experienced was mild and only one patient discontinued as a result of this by W12. In two randomised crossover studies, the equivalent mean pain scores for adalimumab preparations containing citrate [40 mg in 0.8 mL] and citrate-free [40 mg in 0.4 mL] are 30 and 20, respectively.19 It is recognised that pain perception is subjective and multiple factors may influence this, including the inclusion of citrate as an excipient, volume of injection, and needle size.25 There may be differences in injection-related pain between the prefilled pens or syringes. Patients were offered the choice of either formulation to administer their medication, and the opportunity to try a different formulation if the first was not tolerated.

There is a clear gap in the evidence base and prescribing information as to the optimal time to transition patients established on IV vedolizumab to SC. The serum vedolizumab concentration immediately before the Week 6 dose of the standard IV loading regimen is similar to the Ctrough,ss achieved with SC administration, whereas the Ctrough,ss with IV administration is significantly lower [27.9, 34.6, and 11.2 mg/L, respectively].12,20 When SC administration is started at the time that the next IV dose is due, as per the manufacturer’s licensed dosing, a simplified pharmacokinetic model suggests that it may take approximately four doses [8 weeks] to achieve 90% of the higher Ctrough,SS associated with SC administration [Figure 7]. When transitioning patients established on IV vedolizumab, consideration should be given to administering the first SC dose at the point where the drug level is predicted to be similar to the Ctrough,SS expected with SC administration to avoid this, approximately 28 days after the last infusion. Further work is required to explore possible clinical outcomes associated with this.

![Predicted serum vedolizumab concentration when transitioned [Day 0] from IV [red] to SC [blue] administration; [A] at Week 6 following standard IV loading doses at Weeks 0 and 2, [B] at IV steady state trough, and [C] 28 days after the last infusion at steady state. IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ecco-jcc/16/6/10.1093_ecco-jcc_jjab224/1/m_jjab224f0007.jpeg?Expires=1750191103&Signature=ejSBxv57nfiBfLWyuW0MfkrQcT9jG4RIWvwN0sP6r-pk4waSFUFykxi9Zye2R39qnYAPZbLT6J1QdsYWWnL7fGOWhhnCFgo8U~MwCtVhGkhE4HGDp46q57N2vWTCTZS0W7Jjwp3a3Vg~dB9uGgECriF6~jkyKhWYS3n32mIZi6RuGyOT3YV~b8Fyo6IjFewhLuImBvYf6Kq6QrLQTEYY3boyQDefYLZPpZjFalzjWnpo6dDarvycHrjDUX6-4snGct5nUDv-g5Eu~gSfX7eGmT9E~TErGD7B2xeW2bLS5iVs18xu3xWKBcWcgUx4poqPQ~ximhtbFsan9OSzzvxHMg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Predicted serum vedolizumab concentration when transitioned [Day 0] from IV [red] to SC [blue] administration; [A] at Week 6 following standard IV loading doses at Weeks 0 and 2, [B] at IV steady state trough, and [C] 28 days after the last infusion at steady state. IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous.

Multiple studies have demonstrated improved outcomes with increasing vedolizumab exposure,12,26 and patients in this evaluation showed improved remission rates with higher quartile serum trough Ctrough,ss. A reduction in peak and trough fluctuations of serum vedolizumab concentration with SC administration of vedolizumab 108 mg Q2W is expected, compared with IV administration at the standard dose of 300 mg Q8W, although the average serum vedolizumab concentrations have been demonstrated to be similar.27 A potential target trough vedolizumab concentration of 12.7 mg/L has been proposed for IV administration,26 although this target is likely to be dependent on the dose and frequency and therefore on the route of administration, with a higher target trough concentration required with SC vedolizumab. This suggests that trough drug concentration in itself may not be the best predictor of clinical response but may be useful as it does relate to other potentially more relevant measures, such as area under the curve or average serum concentration.

Patient experience has been positively associated with adherence to treatment and therapeutic outcomes.28 Patient satisfaction with changes in medication administration is an essential element of successful switching of treatments. Patient satisfaction following transition was high, predominantly because of increased convenience. Attending for regular infusions is an inconvenience for some groups of patients, such as for those who are employed or with child care responsibilities, and if relatives are relied upon for transport. An initial concern was that this patient group may miss the regular contact with health care professionals in the infusion unit. However, almost all patients [97%] reported feeling at least somewhat supported during this transitioning programme. Some patients cited reassurance from the established local IBD telephone helpline and online messaging portal. Careful counselling supported by written materials and a planned review following the transition were also important in making patients feel supported and for avoiding nocebo effects.

There have also been multiple benefits to the health service, including a significant reduction in drug acquisition costs and reducing waiting times for first appointments at the infusion unit. It has been shown that medication costs are the predominant component of health care costs associated with treating IBD,29 and so minimising these is essential. Adequately resourced pharmacy homecare teams and clinical nursing teams are essential to the success of the transition.

There are several limitations of this service evaluation. The evaluation was performed at a single centre, and follow-up was limited to a single episode at 12 weeks following transition. Although this is a relatively short period of time, it was a reasonable time to evaluate any possible change in efficacy. The transitioning programme needed to be adapted after the service evaluation was under way, with some patients having their first SC dose at their baseline review and the remaining cohort having the first dose in place of their next IV infusion. This change was made to ensure that there would not be a delay to patients receiving further doses of SC vedolizumab. Mucosal healing is an increasingly important outcome measure in IBD studies.30 However, this would have been inappropriate as part of a service evaluation, particularly with the ongoing COVID-19 pressures on endoscopy units. A strength of this study is that all the patients in a heterogeneous IBD population treated with vedolizumab were offered the opportunity to transition, as opposed to a formal research study setting where patients may have been excluded. Despite these limitations, this real-world service evaluation supports the transitioning of patients established on IV vedolizumab to home-administered SC vedolizumab through a planned programme.

A SC formulation of infliximab has been approved for use but, again, is based on evidence obtained from naive patients, with limited evidence about transitioning patients established on IV infliximab. Generation of similar real-world evidence of effectiveness and safety for this is essential.

In conclusion, use of SC medications in IBD is established and increasing options for patients preferring home administration is welcome. Transitioning patients established on IV vedolizumab to SC appears to be safe and effective, with high patient satisfaction and multiple benefits for the health service. The optimum timing of the first SC dose in patients established on the IV formulation of these drugs is yet to be determined. Consideration should be given to offering a similar transitioning programme to relevant patients treated with vedolizumab and other medicines in other disease areas.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients for agreeing to participate in this service evaluation, the IBD team, infusion unit staff, and pharmacy homecare team at UHS for their ongoing support. We acknowledge management support from James Allen [chief pharmacist] and Gavin Hawkins [divisional director of operations] at UHS.

Funding

No specific funding has been received for this work. Data were generated as part of routine work at UHS.

Conflict of Interest

FC has served as consultant, advisory board member, or speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Celltrion, Falk, Ferring, Gilead, Janssen, MSD, Napp Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, Sandoz, Biogen, Samsung, Tillotts; and Takeda; he has received research funding from Biogen, Amgen, Hospira/Pfizer, Celltrion, Takeda, Janssen, GSK, and AstraZeneca. DY has received support from Sandoz for meeting attendance and travel. MB has served as an advisory board member and received lecture fees and honoraria from Abbvie, Dr Falk, Hospira, Janssen, MSD, Napp Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, and Pfizer. EV has received honoraria from Pharmacosmos and Tillotts Pharma. MG has received support for meeting attendance, travel, and/or honoraria from AbbVie, Falk, Janssen, MSD, Biogen, and Takeda. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

EV, SR, DY, CH, MB, and FC designed the switching programme and wrote the paper. EV, SR, DY, CH, MB, HM, and ML collected and analysed the data. RF, TS, and MG critically reviewed the content on the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.