-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Naoki Kokaze, Takeshi Fushimi, Yusuke Nakamura, Contabilizar el comercio imperial: analysis of early double-entry accounting books with TEI/DEPCHA, Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, Volume 40, Issue Supplement_1, January 2025, Pages i39–i45, https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqae032

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This article discusses the encoding of double-entry accounting books from the 16th-century Spanish Empire and presents initial stage results from analyzing the encoded text, based on our case study. We selected the accounting books containing transactional data from 1558 to 1560. The encoding process followed the Text Encoding Initiative proposed by the Digital Edition Publishing Cooperatives for Historical Accounts (DEPCHA), with some additional attributes specific to the ontology of the double-entry books. The article explains the method of encoding and describes the unique characteristics of the ledger, such as the format of bookkeeping and the spatial arrangement of information. We adopted DEPCHA’s markup methodology to represent the accounting vocabulary and used the @ana attributes to invoke a domain ontology for bookkeeping structure of transactions. The results from the data analysis focus on three aspects: identification of person names, accounting terms, and checking the balance of payments. The study concludes by highlighting our contribution to expanding new semantic vocabularies within the DEPCHA’s Bookkeeping Ontology, namely “bk: Total” and “bk: SubTotal.” It illuminates the flexibility in name spelling and the preference for mundane vocabularies in the left column of the ledger, while emphasizing accuracy in numerical values and calculations in the right column. We propose further encoding and analysis of transactional records to enhance the understanding of historical double-entry commercial records.

1. Introduction

Accounting books of the past offer us valuable insight for understanding economic history, and this is also true for the history of the Spanish Empire. During the 16th century, when Spain experienced unprecedented overseas imperial expansion, merchants began to record their commercial transactions using the newly introduced double-entry bookkeeping method in order to quantify financially (contabilizar in Spanish) their activities and to secure their business in the New World full of uncertainty. Also, the Spanish Crowns considered such bookkeeping as a way to oversee the status of the Spanish imperial commerce (comercio imperial). As numerous scholars have been working with these double-entry records, we believe that their digital encoding might help the analysis of containing information in a broader way.

This article, based on our case study, discusses how to encode historical double-entry accounting books and offers initial stage results obtained from the analysis of the encoded text. All of the original figures and tables are accessible to browse at our GitHub page (https://naoki-kokaze.github.io/earlyModernSpanishLedger/). For encoding purposes, we have adopted a modified version of the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) proposed by Digital Edition Publishing Cooperatives for Historical Accounts (DEPCHA), although we added some attributes specific to the ontology of the double-entry books.1

This ontological amplification is one of our significant contributions, which will be discussed in this article. We also demonstrate that the encoded text can be employed not only to reconstruct the commercial activities of the merchants but also to understand the function assigned to the historical accounting book.

2. Description of source

There survive several accounting books of 16th-century Spain, written with the double-entry bookkeeping method. We have picked out as an example a pair of accounting books among those deposited in the Archive of Burgos Provincial Congress (http://mosa.burgos.es/_20_ArchivodelaDiputacion.aspx). Specifically, we have chosen two books belonging to the Salamanca Company (Compañia de García y Miguel de Salamanca), which contain transactional data for the 3 years from 1558 to 1560 (classified as CM32 and CM108). Burgos was one of the major centers of the Spanish imperial commerce, and the Company specialized in woolen export and international monetary transfer (González Ferrando 2010).

In the double-entry system, at least two types of books are required. The first is the journal (diario in Spanish), in which all transactions are recorded in chronological order. The second book is the ledger (libro mayor or libro de caja in Spanish). In the ledger, each transaction in the journal must be transcribed twice: one on the left page as a debit transaction and the other as a credit on the right (cf. Fig. 1).

A sample page of the ledger (©Archivo de la Diputación de Burgos).

The information of each transaction in the ledger is structured at least in two columns: details of the transaction on the first column and value of the transaction on the second. The first column is much wider than the second column. On this column, the transaction is described in a free text style in which we find rich information such as the name of the counterparty, date and place of the transaction, merchandise and its price and quantity, names of other parties involved in the transaction, terms of the transaction, and the number of pages where the other transcription of the same transaction can be found. The second column, on the other hand, contains only the monetary value of the transaction, expressed in Roman numerals.

Several related transactions in the left page are grouped together by an accounting title, and they constitute a single set. At the end of the second column of each set, there can be found the total amount of all transactions in the set, also expressed in Roman numerals. Each set in the left page has its corresponding set in the opposite right page, which has a total amount equal to that of the left page.

With these two characteristics—the double transcription from the journal and the spatial arrangement of the information, the ledger has more complex structure than the journal in the double-entry system. Thus, at the present stage of our project, we concentrate on exploring the method of marking up the ledger, so that we can capture contained information in a more thorough and precise manner.

To start encoding, we sampled ten of 201 spread pages of the ledger. These pages contain the transcription of transactions recorded in the initial pages of the corresponding journal. We have marked up all transactions that appeared in those ten pages. In the following section, we explain the method employed for our encoding.

3. Method of encoding: analytical framework

Let us analyze the methods of structuring accounting documents. In contemporary accounting practice, XBRL (eXtensible Business Reporting Language) serves as the standard for structuring financial statements. XBRL provides a multilingual vocabulary for expressing the relationships among account items and elements, and it is possible to define one’s own vocabulary, making it feasible to structure text-type accounting records by utilizing inline XBRL.

However, even though the principles of double-entry bookkeeping have remained consistent since its inception, its actual operation is highly transaction-specific and has undergone cumulative changes as commercial activities have become more complex. Consequently, the application and interpretation of the principles have not been stable, not only for later analysts but also for those who were involved in transactions in the same period. To comprehend both the consistency of the principles and the diversity of their application, it is a potent approach to follow the TEI, enabling markup that records the accounting practices of the time, rather than applying modern accounting and information processing concepts to historical cases using XBRL.

As previously mentioned, the purpose of this study is to structure the unique characteristics of the historical double-entry ledger, such as the format of bookkeeping and the spatial arrangement of information. To achieve this goal, we conform to the TEI, which allows us to express the linguistic and stylistic information of historical accounting documents.2 Additionally, we adopted the markup methodology proposed by DEPCHA that extends the TEI to represent the unique vocabulary of accounting (https://gams.uni-graz.at/depcha).

DEPCHA has developed a domain ontology, based on the concept of “Transactiongraphy” (Tomasek 2013; ,Tomasek and Bauman 2013; ,Tomasek 2016), for extracting machine-readable data in Resource Description Framework (RDF) format from transactional information in accounting records in the TEI or Comma Separated Values (CSV) format. A member of the DEPCHA states that their future challenge is to normalize the vocabulary of words such as “currency” and “item” in accounting records that emerge from various case studies and to build an interoperable data model for open data (Pollin 2019), but at present, there are not so many case studies using DEPCHA. Furthermore, concrete examples of double-entry books, which are considered as the basis of accounting practice in the modern world, have not sufficiently been marked up using the DEPCHA scheme. Our research will contribute to filling this gap and giving practical feedback to DEPCHA. We also think that more normalized TEI/DEPCHA can make the analysis of historical financial data more efficient, when the scale of data becomes bigger. Practically speaking, when marking up, DEPCHA requires one to assign attribute values, using @ana attribute, to the TEI document, so that a domain ontology is invoked that describes the transactional structure in the RDF format.3

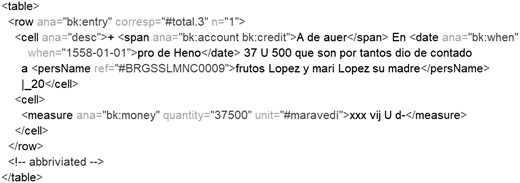

For example, by using “bk: money,” an attribute proposed by DEPCHA, we can markup monetary values, while maintaining their original expressions in Roman numerals. Other attributes, such as “bk: credit” and “bk: debit”, are also useful for marking up a double-entry ledger, for one of their main characteristics is the classification of transactions by credit and debit, as explained in the previous section.

Let us explain our markup framework. One of the major challenges that we face has been how to markup the balance of debit and credit transactions. As mentioned earlier in the materials section, each unit of transactions in the left page has its corresponding unit in the opposite page, so the facing page needs to be structured as a coherent space when marking up (cf Fig. 2 for the debit side, and Fig. 3 for the credit side). When we started our markup, DEPCHA allowed for a description of a “single transaction” structure. While following DEPCHA’s recommended policy of using <table> tags to structure the transaction information in a tabular form,4 we ensure that the @ana attribute value is entered in a human-readable form—though it is not completely machine-processable for the moment—so that the correspondence between the left and right pages is clearly indicated.

4. Results from data analysis

The marked-up data can be used not only to analyze commercial activities of the Salamanca Company but also to detect how their accounting book itself was functioning. The bookkeeping has been an important technology for the merchants to track their transactions precisely. Without such precision, any exact payment cannot be possible for them and their trading partners. Thus, one of the central concerns of the bookkeepers, we consider, consisted in how to record transactions in accurate and clearly identifiable ways. For this reason, our analysis focuses on how the accuracy of transactions is ensured in the ledger records.

We retrieve information from the TEI/XML file in order to conduct analysis by using Python (especially BeautifulSoup4). So far, we have analyzed the encoded data in three ways: (1) identification of person names, (2) accounting terms, and (3) checking the balance of payments; all of them are available to browse at our GitHub page (https://naoki-kokaze.github.io/earlyModernSpanishLedger/).

4.1 Identification of person names

The identification of the names appearing in the accounting records is very important for the bookkeepers to conduct transactions, as well as for the historians who employ such data in their research. However, we found persons with different spellings in our records, because the rules of Spanish orthography were not yet established in the 16th century. So, we ask how bookkeepers overcome this divergence in name spelling so as to identify a specific person.

In our encoding, we have assigned the <persName> element for each person with “@ref” attribute linking with “@xml: id” attribute defined in the <listPerson> in the header, and this element lets us extract the variation of spellings. There appear forty-five individuals in our sampled pages of the ledger. Thirty-seven of forty-five cases do not show spelling variations, because they appear only once in the pages we encoded. The rest of the cases have some sort of variations. Table 1 lists the four individuals who have the most name variations. For example, the name “Pedro de Caballos” appears four times with two abbreviated spelling variations: “P'o de Cauallos” or “Cauallos.” We also note the use of pronouns such as “le” and “les” as can be observed in the fourth case.

Variations on the names of people mentioned in the ledger (the first four cases).

| Unified notation of the person names . | Variations of the person names . |

|---|---|

| Miguel de Salamanca | migl de sa; miguel de sa; miguel de sa; miguel de salamanca; migel de sa |

| Alonso de Beguillas | Alonso de beguillas; ao de beguillas; ao de beguillas; ao de beguillas; ao de beguillas |

| Pedro de Caballos | po de cauallos; po de cauallos; cauallos; cauallos |

| Pedro López | po Lopez; le; les |

| Unified notation of the person names . | Variations of the person names . |

|---|---|

| Miguel de Salamanca | migl de sa; miguel de sa; miguel de sa; miguel de salamanca; migel de sa |

| Alonso de Beguillas | Alonso de beguillas; ao de beguillas; ao de beguillas; ao de beguillas; ao de beguillas |

| Pedro de Caballos | po de cauallos; po de cauallos; cauallos; cauallos |

| Pedro López | po Lopez; le; les |

Variations on the names of people mentioned in the ledger (the first four cases).

| Unified notation of the person names . | Variations of the person names . |

|---|---|

| Miguel de Salamanca | migl de sa; miguel de sa; miguel de sa; miguel de salamanca; migel de sa |

| Alonso de Beguillas | Alonso de beguillas; ao de beguillas; ao de beguillas; ao de beguillas; ao de beguillas |

| Pedro de Caballos | po de cauallos; po de cauallos; cauallos; cauallos |

| Pedro López | po Lopez; le; les |

| Unified notation of the person names . | Variations of the person names . |

|---|---|

| Miguel de Salamanca | migl de sa; miguel de sa; miguel de sa; miguel de salamanca; migel de sa |

| Alonso de Beguillas | Alonso de beguillas; ao de beguillas; ao de beguillas; ao de beguillas; ao de beguillas |

| Pedro de Caballos | po de cauallos; po de cauallos; cauallos; cauallos |

| Pedro López | po Lopez; le; les |

The first three cases are the ones with the largest deviations. Therefore, we investigated minutely the description and contexts of these documents to identify the stakeholders of these transactions. It has turned out that Miguel de Salamanca was a co-founder of the Salamanca Company. The other two, Alonso de Beguillas and Pedro de Caballos, were the collaborators of the Company, since they were responsible for the purchase and transport of woolen of the Company. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that those involved in the company’s business are more likely to be spelled in multiple ways. The bookkeeper could identify them easily without standardized spelling, because they were well-known persons for the members of the Company. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that those involved in the company’s business could spell their names in irregular abbreviated forms to economize their time and effort of bookkeeping. Also, we consider the contextual information helpful for the name identification by the modern researchers.

4.2 Accounting titles and abbreviations

Using the @ana attribute value “bk: account” defined in DEPCHA’s Bookkeeping Ontology, we extracted the terms used to transcribe the entries from the journal to the ledger. The results are shown in Table 2. A closer examination of the accounts reveals that the difference in the frequency of use of each expression can be explained by the position in the dataset where each expression is used.

| Entry . | Accounting vocab. in debit . | Accounting vocab. in credit . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Deue | A de auer |

| 1 | Dio | Dio |

| 1 | Dio | dio |

| 1 | <!-- similar expressions repeat afterwords --> | <!-- similar expressions repeat afterwords --> |

| 1 | pago | |

| 1 | pago | |

| 1 | pago | |

| 1 | <!-- similar expressions repeat afterwords --> | |

| 2 | deue | A de auer |

| 2 | dio | |

| 3 | deuen | An de auer |

| 3 | Dio | |

| 4 | deuen | An de auer |

| 4 | dio |

| Entry . | Accounting vocab. in debit . | Accounting vocab. in credit . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Deue | A de auer |

| 1 | Dio | Dio |

| 1 | Dio | dio |

| 1 | <!-- similar expressions repeat afterwords --> | <!-- similar expressions repeat afterwords --> |

| 1 | pago | |

| 1 | pago | |

| 1 | pago | |

| 1 | <!-- similar expressions repeat afterwords --> | |

| 2 | deue | A de auer |

| 2 | dio | |

| 3 | deuen | An de auer |

| 3 | Dio | |

| 4 | deuen | An de auer |

| 4 | dio |

| Entry . | Accounting vocab. in debit . | Accounting vocab. in credit . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Deue | A de auer |

| 1 | Dio | Dio |

| 1 | Dio | dio |

| 1 | <!-- similar expressions repeat afterwords --> | <!-- similar expressions repeat afterwords --> |

| 1 | pago | |

| 1 | pago | |

| 1 | pago | |

| 1 | <!-- similar expressions repeat afterwords --> | |

| 2 | deue | A de auer |

| 2 | dio | |

| 3 | deuen | An de auer |

| 3 | Dio | |

| 4 | deuen | An de auer |

| 4 | dio |

| Entry . | Accounting vocab. in debit . | Accounting vocab. in credit . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Deue | A de auer |

| 1 | Dio | Dio |

| 1 | Dio | dio |

| 1 | <!-- similar expressions repeat afterwords --> | <!-- similar expressions repeat afterwords --> |

| 1 | pago | |

| 1 | pago | |

| 1 | pago | |

| 1 | <!-- similar expressions repeat afterwords --> | |

| 2 | deue | A de auer |

| 2 | dio | |

| 3 | deuen | An de auer |

| 3 | Dio | |

| 4 | deuen | An de auer |

| 4 | dio |

When a dataset contains several transactions, the first transaction uses accounting vocabularies such as deue (debit) and A de auer (credit).5 However, from the second transaction onward, more quotidian expressions such as pago (paid) and dio (delivered) are more frequently used. In the debit side, the expression dio used after the second transaction has the same meaning as the accounting vocabulary (deue) in the first transaction. Likewise, the word pago in the credit side is used as the casual expression of the A de auer (or An de auer in plural) that appeared in the first transaction of each dataset. The word dio in the credit side requires more careful read of the transactional description. Here, the dio does not represent the A de auer, but means that the transactional counterparty gave (dio) some money or any other valuables to the third party on behalf of the Salamanca company. Such transaction must be recorded as a credit of the counterparty. Therefore, we consider that the bookkeeper preferred to use the everyday expressions rather than to repeat the accounting terminologies. And the meanings of such vocabularies can better be established with the help of the surrounding text. This observation confirms the importance of consulting the contextual information we mentioned in the analysis (1) on the abbreviated names.

4.3 Checking the balance of payments

The precision of calculation is another important factor that can guarantee the trustworthiness of accounting books. In the case of a double-entry ledger, the total amount of all transactions grouped as one debit set on the left page must be equal to the amount of the corresponding credit set on the right page.

It seems that the use of Roman numerals in our materials can make calculating the total amount difficult. So, we want to ask how accurate the values of the total amount found in our materials are. As we have added manually in our encoding Arabic numerals,6 equivalent to the values expressed originally in Roman numerals, by using @quantity attribute of <measure> element with DEPCHA’s “bk: money” attribute, such verification becomes feasible. Table 3 shows some of the results of the calculations of the balance of payments on the page 35 of the ledger.

| Debit side . | . | . | . | . | . | Credit side . | . | . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry No. . | Text . | Status . | Amount . | Sum . | Check BP . | Entry No. . | Text . | Status . | Amount . | Sum . | Check BP . |

| entry.1 | +Alonso de beguillas deue En pro de Henero 170 U… | deue | 170000 | entry.1 | + A de auer En pro de Heno 37 U 500 que… | A de auer | 37500 |

| Debit side . | . | . | . | . | . | Credit side . | . | . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry No. . | Text . | Status . | Amount . | Sum . | Check BP . | Entry No. . | Text . | Status . | Amount . | Sum . | Check BP . |

| entry.1 | +Alonso de beguillas deue En pro de Henero 170 U… | deue | 170000 | entry.1 | + A de auer En pro de Heno 37 U 500 que… | A de auer | 37500 |

| Debit side . | . | . | . | . | . | Credit side . | . | . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry No. . | Text . | Status . | Amount . | Sum . | Check BP . | Entry No. . | Text . | Status . | Amount . | Sum . | Check BP . |

| entry.1 | +Alonso de beguillas deue En pro de Henero 170 U… | deue | 170000 | entry.1 | + A de auer En pro de Heno 37 U 500 que… | A de auer | 37500 |

| Debit side . | . | . | . | . | . | Credit side . | . | . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry No. . | Text . | Status . | Amount . | Sum . | Check BP . | Entry No. . | Text . | Status . | Amount . | Sum . | Check BP . |

| entry.1 | +Alonso de beguillas deue En pro de Henero 170 U… | deue | 170000 | entry.1 | + A de auer En pro de Heno 37 U 500 que… | A de auer | 37500 |

The results agree with the amounts recorded in the account book. This suggests that the calculation of amounts and totals in the ledger was accurate, as one would expect with merchants.

5. Concluding remarks

As conclusion, we present the achievements of this study from the perspectives of Digital Humanities and historiography. First and foremost, we would like to stress that the newly developed DEPCHA’s Bookkeeping Ontology has adopted the concepts and semantic vocabularies of “bk: Total” and “bk: SubTotal” (cf https://gams.uni-graz.at/archive/objects/o:depcha.bookkeeping/methods/sdef:Ontology/get), as a result of the discussion between us and the developer of DEPCHA, Christopher Pollin. This decision is mainly based on our third case study to verify the balance of the amounts in the credit and debit columns of the double-entry bookkeeping system, among other things.

Second, as far as our analysis of the encoded data in the left column of description is concerned, we have observed that the bookkeepers tolerated the flexibility of name spelling and preferred the mundane vocabularies to the financial terminologies, as long as they could identify its meaning. For such identification, the bookkeepers must have invoked their and other corporate members’ memories, not presented explicitly in the documents. However, probably it was an optimal ignorance to sustain their daily business in the expanding Spanish Empire. For the researchers in the present day, on the other hand, such memory and context are beyond the reach, but can be inferred reasonably to some extent by examining the contextual information found in the ledger and other related documents. By combining with such historiographical investigations, we can make the encoding of irregular terms more consistent and less ambiguous.

In the right column, on the contrary, we found that the bookkeepers paid more attention to ensure the accuracy of the numerical values and calculations. It must have been a painful work for the bookkeepers requiring “a capacity for sustained concentration, attention to detail, and a passion for accuracy”, but indispensable to avoid any dispute in the payments (cf Nordhaus 2007). For modern researchers, it is not an easy task at all either to verify the numeric values handwritten in the historic accounting books. And yet, even though still requiring time and efforts, the systematic encodings following DEPCHA framework facilitate the verification of the accounts significantly.

In sum, we consider that there existed an optimal balance between the tolerance for the flexible expressions in the left column and the rigor of the calculations in the right column in the double-entry bookkeeping practices of those merchants in the 16th-century Burgos. And it is the task of modern researchers to search for the appropriate balance between the close historiographical investigation and the systematic encoding framework to further the study of the history of commercial transactions and their records.

Above are the conclusions that we have drawn so far from our marked-up data. For further analysis, we need to encode more transactional records. As we find that there remain several ledgers of Salamanca’s Company and each of them has more than a hundred of pages, we need some strategies for further encoding. As we have not yet established any reliable handwriting recognition model for the early modern Spanish historical documents using software, such as Transkribus, nor an extensive network of the collaborators that can make a crowd sourcing possible, we think that a data sampling is required, for the question of time efficiency. One possible direction is to encode all records of every several pages of the ledger we are encoding. With this method, we can analyze, for example, the seasonal patterns of the transactions, such as fluctuation of price or volume. Another direction is to extract a certain number of pages from every ledger and to encode the records contained in them. This strategy makes possible the analysis about the tendency over years of transactions. Both directions, we believe, also help us to enrich and modify our encoding framework, in order to structure more precisely the historical double-entry commercial records. Thus, we can contribute to further investigation of the early modern commerce of the Spanish empire and the wider world.

Author contributions

Naoki Kokaze (Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing—original draft), Takeshi Fushimi (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing—original draft), Yusuke Nakamura (Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing)

Funding

This research was supported by the JSPSKAKENHI (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research) 18H00786: The Investigation of the Process of Formation, Development and Transformation (Decline) in the Modern Hispanic World.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Footnotes

When considering such a project-specific encoding, the general recommendation is to create a TEI ODD file (Bauman 2019–2020). However, our aim is to explore how the existing tag sets can be effectively utilized. DEPCHA holds significance in its ability to extract transactional structures without influencing the structures one would wish to express with the TEI. Given the emphasis on the utility of DEPCHA, we consider that there is no necessity, in our case study, to propose an alteration to the TEI, via ODD.

Although not pursued this time, as more cases of similar markup accumulate, it would become more feasible to map them to XBRL. We hope for further progress in discussions with like-minded individuals.

A tag set <annotation> has recently been introduced to represent RDF-like descriptions within the TEI files. This enables one to encode supplementary information when assigning values to the @ana attribute (such as who interpreted it) to be described within the <standOff> tag, the parent element of <annotation>. On the other hand, DEPCHA has been developing its semantic ontologies to extract transactional structures inherent in the TEI documents using RDF graphs (Vogeler 2017) . In our case study dealing with transactional information with RDF, we consider that DEPCHA’s Ontology is more suitable than the <annotation> tag set defined in the TEI.

Some readers may feel uneasy about structuring archival descriptions that seem not to be explicitly visually tabular, using the <table> element. However, considering the long tradition of structuring information of accounting records in tabular formats since ancient times (Nissen et al. 1994; Jute 1996), we have chosen to adhere to the recommended use of the <table> element proposed by DEPCHA.

We have maintained the spelling of these vocabularies as appeared in the source, without modernizing them. Their corresponding modern spellings are debe, ha de haber, han de haber, pagó and dió.

For the future task in encoding, it is reasonable to use an existing XSLT stylesheet that can convert automatically Roman numerals into Arabic ones. cf https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/xslt-cookbook/0596003722/ch02s03.html